ADOPTION OF MOBILE SERVICES IN FINLAND

Conceptual Model and Application-based Case Study

Mari Ervasti and Heli Helaakoski

VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland, Kaitoväylä 1, P.O. Box 1100, FI-90571 Oulu, Finland

Keywords: Adoption, Mobile service, TAM (Technology Acceptance Model), TPB (Theory of Planned Behaviour),

J2ME, Finland.

Abstract: This paper offers both theoretical and empirical contributions relating to the consumers’ motives for and

barriers to adopting mobile services. A case study of a mobile service is introduced to validate the factors

that facilitate and trigger, and respectively hinder the acceptance of mobile services in Finland. The factors

affecting the service adoption were researched based on a conceptual model that was a modified version of

the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and of the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB). Based on the

findings from a survey conducted with a sample of 52 Finnish campus students, the factors that affect

consumers’ attitudes towards mobile services were discovered. Usefulness was revealed to have the

strongest impact on attitude towards a mobile service, with context information and attitude acting as

significant determinants of the intention to use the service. This study attempts to help mobile service

providers choose right development and marketing strategies for mobile services and enhance the adoption

and diffusion of mobile services.

1 INTRODUCTION

For a long time Finland has been a European pioneer

for testing new mobile services. But even in Finland,

the adoption of mobile services has been modest and

the most popular services are still based on SMS

messaging. Current mobile services do not fulfil the

requirements set by the users since the services have

been developed based on technological development

instead of users’ needs. According to Moore and

McKenna (1999) the mobile services are at the

chasm, the pioneering and early adopters are using

the services, but the masses have not yet followed

their lead. Many researches (Hyvönen and Repo,

2005; Bouwman et al., 2007) have studied the

factors that affect the adoption of mobile services in

the Finnish context but there is still a need to

evaluate the adoption factors in real-life case studies.

Kaasinen (2005) has studied the user acceptance of

mobile services by using the Technology

Acceptance Model (Davis, 1989) and built user

acceptance on four factors: perceived value of the

service, perceived ease of use, trust, and perceived

ease of adoption. Bouwman et al. (2007) have

researched mobile service adoption from the

perspectives of physical, cognitive, security and

economic barriers, and from the perspectives of the

perceived entertainment value and perceived

flexibility benefits of mobile services. Finnish

consumers’ usage of mobile services has been

studied in a report for National Consumer Research

Centre by Hyvönen and Repo (2005). The report

focuses on mobile services that Finnish people use,

the motives for and obstacles to using the services,

and the readiness to pay for mobile services.

The success of mobile services is not only

depending on technological maturity of mobile

technology and the penetration of mobile handsets;

in the end, eventually the users decide on the success

of the services. The predictions are hard to make, but

there are certain factors that need to be considered

when developing mobile services. Muller-Veerse

(2000) has identified ubiquity, reachability, security,

convenience and personalisation as the key drivers

for the mobile market today. Rogers (1995) has

developed ‘Rogers’ basic five’ factors, later

increased with two more factors (Moore and

Benbasat, 1991) that influence the adoption and

diffusion of new technologies throughout a social

system: relative advantage, compatibility,

complexity, trialability, observability, image and

131

Ervasti M. and Helaakoski H. (2008).

ADOPTION OF MOBILE SERVICES IN FINLAND - Conceptual Model and Application-based Case Study.

In Proceedings of the International Conference on e-Business, pages 131-139

DOI: 10.5220/0001910301310139

Copyright

c

SciTePress

trust. According to Rogers mobile services are likely

to be adopted if mobile solution has some clear

advantages over existing products or services.

Mobile services should also be compatible with

existing practices, values, and skills of potential

adopters, and easy to understand and use. If it is not

possible to experiment with the service before

making an adoption or rejection decision, and if the

benefits offered by the service are not visible, then

adopters are likely to perceive uncertainty and risk

in adopting the service. Today the mobile phone is

more like a reflection of one’s identity, so if the

adoption and use of mobile service is perceived to

communicate one’s personality and enhance the

image and status, it has more potential to be adopted.

It is also important that the mobile service adopter

perceives the service provider to be trustworthy.

There are several factors inhibiting the use of

services, although the technology maturity is no

longer an obstacle and even so the adoption and

diffusion of mobile services has not yet proceeded as

fast and wide as have been assumed. Development

of technology is commonly seen as an important

prerequisite, or even as a reason, for people to adopt

new mobile services. According to Gillick and

Vanderhoof (2000), the new mobility experience,

i.e. the anytime and anyplace access to desired

products and services, will be the greatest benefit for

the consumer. However, Figge (2004) claims that

the ubiquity alone is not enough to ensure a user

acceptance and the success of a mobile application:

as the user’s problems vary with the context in

which he or she accesses service, the service based

on information of the specific context is likely to

become the user’s favourite. Gilbert and Han (2005)

identified one key barrier of attracting a critical mass

of adopters as the lack of compelling content, and

another as the differences among adoption patterns

in individual market segments. Aarnio et al. (2002)

proposed two major reasons above all inhibiting the

use of mobile services; the high pricing and the

restricted quality of services.

Hyvönen and Repo (2005) have stated that

mobile services are not adopted linearly according to

the assumptions of diffusion theory. Their studies

state that the socio-demographic factors do not

essentially affect the adoption of mobile services;

instead, the best way to explain the use of mobile

services is to research the general attitudes towards

new technology, mobile services and devices. In a

survey by Cheong and Park (2005) conducted in

Korea, perceived playfulness was found to be

influential in predicting the behavioural intention to

use mobile Internet. Whereas findings from a

consumer survey conducted in Finland (Anckar,

2002) indicated that m-commerce adoption mainly

appears to be driven by a need for solutions that add

convenience and flexibility to daily routines rather

than excitement and entertainment. Anckar (2002)

also found out that consumers perceive the ability to

satisfy spontaneous and timecritical needs as the

most important driver of m-commerce adoption.

This paper researches and validates factors that

facilitate and trigger, and respectively hinder, the

adoption of mobile services in Finland. Finland has

been selected as a case country since it is considered

as a pioneer of mobile technologies. In August 2007,

97% of Finns had at least one mobile phone

(Statistics Finland, 2007). The findings from the

survey conducted in autumn 2007 (Invest in Finland,

2008), based on information on four million mobile

phones from three telecom operators, showed that

Finns change their mobile phones every 2.7 years.

More than 70% of the phones in use had a colour

screen and half included a camera. The 3G phones

gained an 18% share of the market, which was more

than double the figure in 2006. In the study in which

participated over 1500 Finns aged 15-64 in year

2006, one quarter of those surveyed reported having

browsed web pages with their mobile phones (It-

viikko, 2007).

Furthermore the paper studies what kinds of

services are likely to be adopted; and how

businesses can enhance the adoption and diffusion of

mobile services. In order to validate the adoption

factors in practice this paper presents a real life case

study of launching the mobile service. The case

mobile service was based on downloadable Java

application, not yet eagerly adopted at least in

Finland. It was tested in a delimited user group of

students and personnel in Finnish campus area in the

field trial. Mobile service offered information about

internal news, events, announcements and schedules

of the study community, as well as a mobile flea

market for buying and selling own things through

mobile channel. The aim of provided services was to

enable easy access for essential information despite

the time and place. Especially students require

multi-channel services due to their mobile lifestyle.

This paper is organized as follows: chapter 2

represents the conceptual model of mobile service

adoption and chapter 3 describes the empirical

evaluation of case mobile service. In chapter 4 the

feedback questionnaire of the case study is presented

and the results of the survey are analysed. The paper

concludes with the limitations of the survey and the

suggestions for future work.

ICE-B 2008 - International Conference on e-Business

132

2 CONCEPTUAL MODEL OF

MOBILE SERVICE ADOPTION

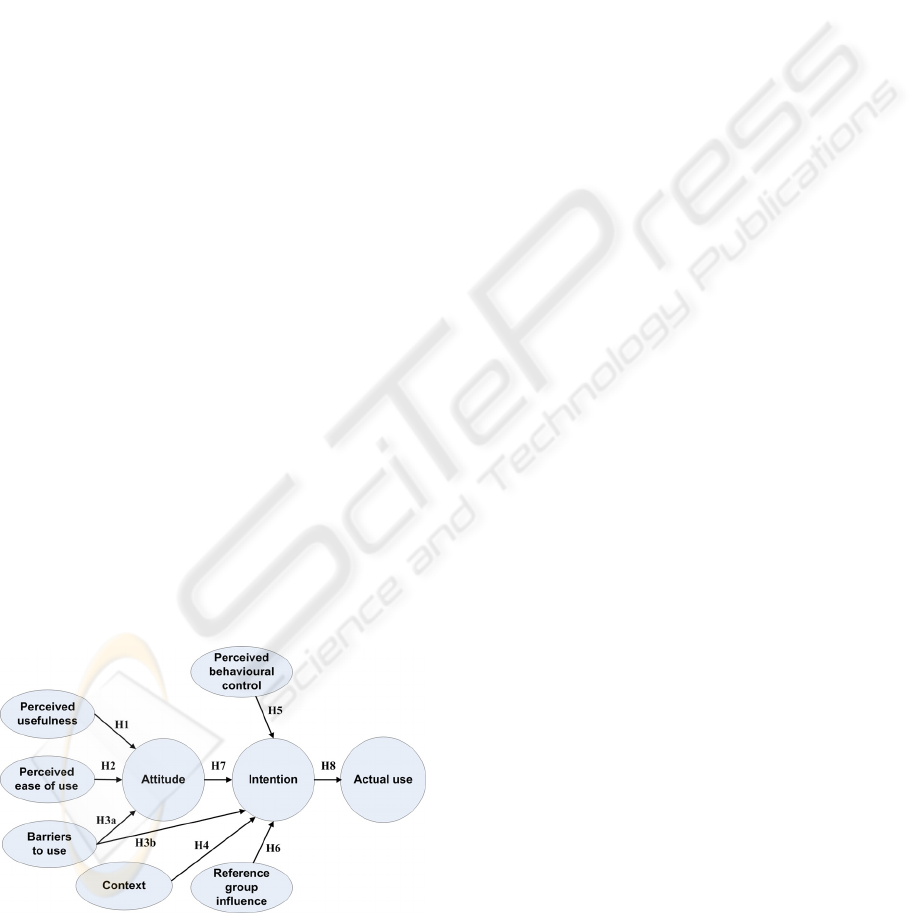

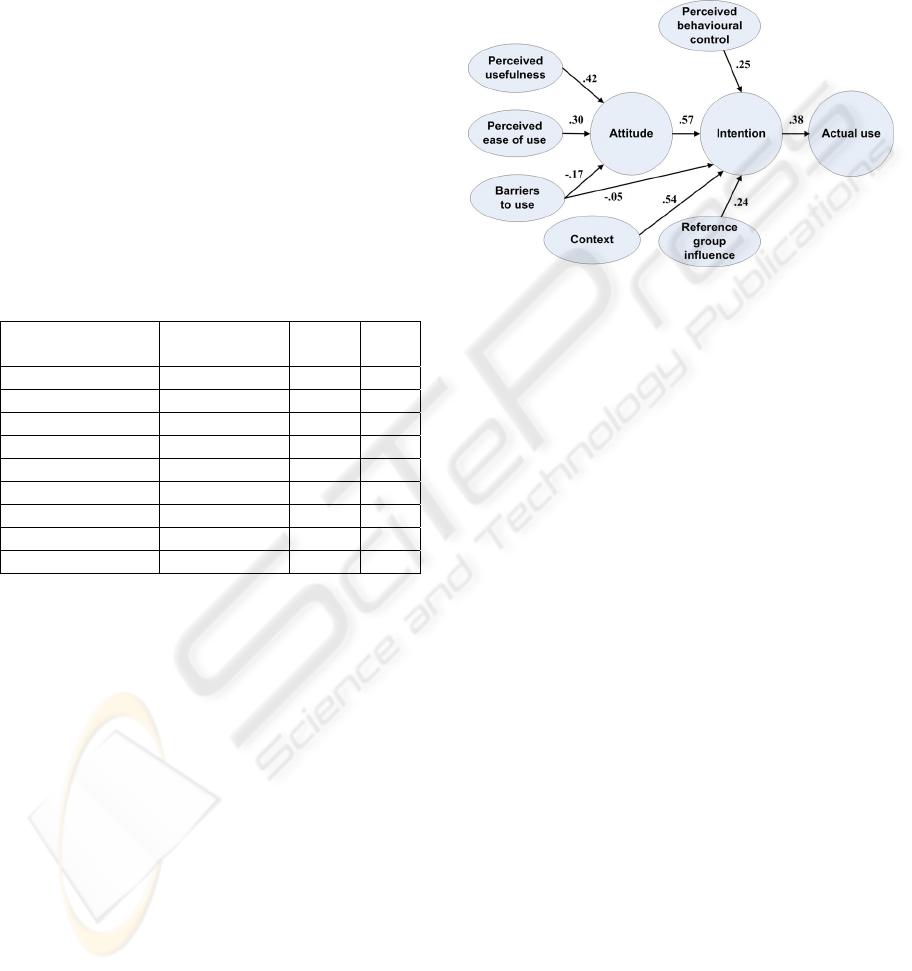

In our study, we developed a modified version of the

Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Davis,

1989) and the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB)

(Ajzen, 1991) for researching the adoption of mobile

services. According to TAM, a consumer’s

behavioural intention to use a “system” is

determined primarily by its usefulness and ease of

use. In TPB, the intention to use a “system” is

explained by attitudes toward a certain behaviour,

subjective norm and perceived behavioural control.

TAM and TPB have both been widely used among

researchers and found to be very useful in explaining

consumers’ attitudes and intentions toward a given

behaviour. TPB is a general theory of human

behaviour while TAM is specific to information

systems.

Studies on acceptance of new technology

indicate that traditional adoption models need to be

extended and modified to better explain the adoption

of the innovations. This study modifies TAM by

proposing additional acceptance factors associated

with mobile services, Rogers (1995) and Figge

(2004) having especially influence on the creation of

construct items stated in Figure 1. Attitudinal

construct was adopted from TPB (e.g. Karjaluoto

and Alatalo, 2007). Mobile service adoption model

was decided to be based on utilitarian-oriented

aspects. Thus, the pure entertainment factors, such

as perceived enjoyment and playfulness were not

included as construct items. Figure 1 shows the

created conceptual model for case mobile service

with causal links between the construct items

(Ervasti, 2007).

Figure 1: Conceptual model for mobile services.

Perceived usefulness (PU), perceived ease of use

(PEOU) and barriers to use (BU) are posited as

antecedents of attitude (ATT) toward mobile

services. Barriers to use are also conceptualised with

context (CON) as an antecedent of intention (INT)

to use mobile services. Perceived behavioural

control (PBC), reference group influence (REF) and

attitude are antecedents of intention, which, in turn,

affects actual use (USE). (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975;

Davis, 1989; Ajzen, 1991; Moore and Benbasat,

1991; Thompson et al. 1991; Davis et al., 1992;

Taylor and Todd, 1995; Venkatesh and Davis,

2000).

Based on the conceptual model in Figure 1, the

following hypotheses for mobile services were

created:

H1: Perceived usefulness of mobile services

positively affects attitude toward mobile services.

H2: Perceived ease of use of mobile services

positively affects attitude.

H3a: Perceived barriers to use mobile services

negatively affect attitude.

H3b: Perceived barriers to use mobile services

negatively affect intention to use mobile services.

H4: Utilisation of context-specific information

on mobile services positively affects intention.

H5: Perceived behavioural control of mobile

services positively affects intention.

H6: Reference group influence positively affects

intention.

H7: Positive attitude toward mobile services

positively affects intention to use mobile services.

H8: Intention to use mobile services is positively

associated with actual use of mobile services.

In order to further evaluate and develop the

conceptual model with related hypotheses, the use

and adoption were tested in a real-life case study of

mobile service.

3 THE EVALUATION OF CASE

MOBILE SERVICE

The practical evaluation of the mobile service

adoption was made in the case study, named Mora.

The case mobile service focused on additional value

of mobility, which means the possibility to access,

produce and send information, products and services

at anytime and from anywhere, regardless of the

user’s location or the time of day. The major aim of

the mobile service was to provide essential

information for the end-users as the administration

of the campus area defined. Mora service was

ADOPTION OF MOBILE SERVICES IN FINLAND - Conceptual Model and Application-based Case Study

133

evaluated in a delimited user group of students and

personnel in Finnish campus area. Mora was

launched at the campus, focused on technology and

economics education, in Finland in September 2007,

in order to research the adoption of mobile services

among campus’ students and personnel.

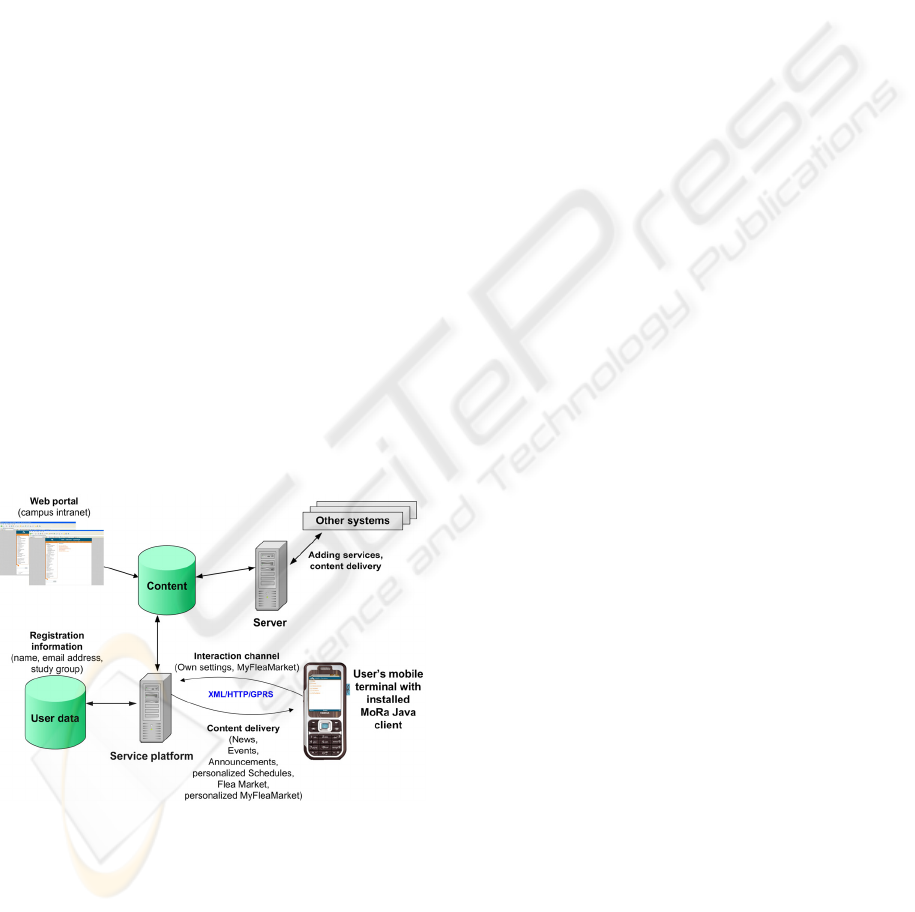

The technical implementation of the case mobile

service is based on a client-server approach to

providing a mobile access to intranet of campus

area. The contents of Mora were internal news,

events, announcements and schedules of the study

community, as well as a mobile flea market. Mobile

flea market enabled users to sell and buy things such

as studying material easily and quickly. In later

development the mobile service could also provide

pleasure, fun, and enjoyment. The mobile client

Mora works as an interaction channel between

customer and service provider by providing

personalised information to the user (Ervasti, 2007).

The server side application carries most of the

functionality. The client side of Mora is Java mobile

application (J2ME) that works in most common

mobile phones.

The main technical building blocks of a

personalised mobile service concept are the service

provider’s existing information systems, mobile

service, customer database and mobile application.

The main building blocks (adapted from Alahuhta et

al., 2005) of the Mora service concept are introduced

in Figure 2:

Figure 2: Overview of the Mora mobile service.

The major source of information for most of the

data and communication processed in the Mora

service is the existing information system, the

campus’ web intranet. This required adaptation of

the content from web-based content to mobile

content. The user database is utilised for providing

personalised services for customers. The existing

database is used as the basic information source for

user-related information (name, email address, study

group), besides the basic personal data the database

could be contain more detailed information on

customer’s special preferences. The mobile end of

the concept utilised mobile Java technologies. The

concept approach of using mobile application has

several benefits both for the end user and the service

provider. Java application provides versatile content

delivery and interaction channel, a service provider

can create a fully branded mobile service concept

and the application is unobtrusive and convenient to

use, avoiding the spam effect. When compared to

browsing, the application-based approach offers

better possibilities for improving usability in mobile

services. In addition, the optimisation of data traffic

between the terminal and servers is easier to

implement in mobile applications. The small size of

the displays also favours application-type services.

The case mobile service started with an

information and marketing campaign advertising

Mora web pages and giving presentations about the

field trial to various student groups and personnel in

the campus area. The purpose was to make the test-

users feel they were privileged to have the mobile

service like Mora exclusively on their campus, and

have the opportunity to participate in the service

testing and development. These initial Mora users

were encouraged to compete for the best

development ideas. In the adoption of application-

based mobile services, the key barrier to overcome is

to get the users to do the first download (Nokia,

2003). Therefore, Mora instructions presented

simple steps for starting the use of Mora as follows:

1) Registration via web page; 2) Downloading the

Mora mobile application via SMS or web page; 3)

Setting up the required connection settings; 4)

Setting up the mobile client preferences.

The test-users were able to post questions for us

during the whole field trial and separate events for

getting help in downloading and installing the

application were arranged to further ease the

adoption process. Users had also an opportunity to

test the Mora service with separate test phones in

case a user’s own mobile phone didn’t support the

application. The nature of the marketing campaign

was selected due to the time and costs limitations. In

future research the diffusion of mobile services by

viral marketing should also be considered and

researched.

ICE-B 2008 - International Conference on e-Business

134

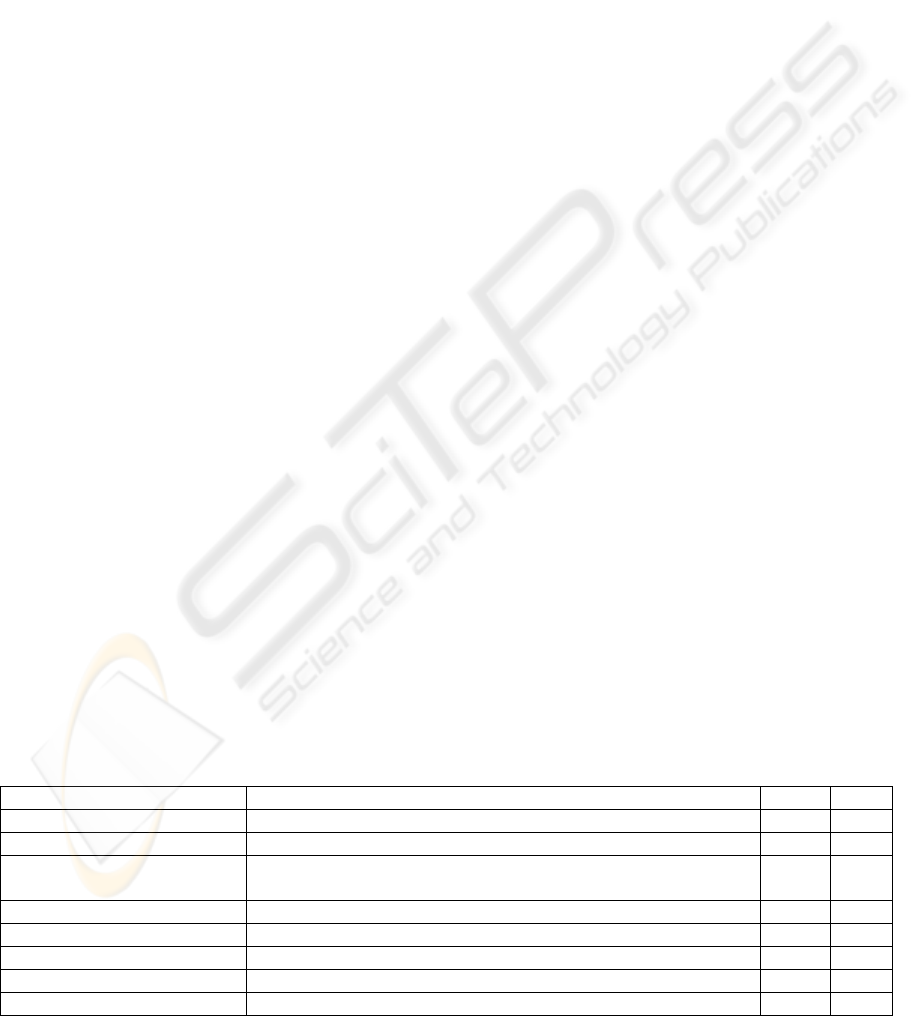

4 FEEDBACK QUESTIONNAIRE

AND ANALYSIS OF THE MORA

MOBILE SERVICE

The feedback from the Mora mobile service was

collected after two months’ field trial through online

and paper questionnaires. The feedback

questionnaire was created based on the hypotheses

in conceptual model (Figure 1). All of the

questionnaire’s construct items consist of multiple

variables, and a five-point Likert scale ranging from

1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with 3

(cannot determine) as a neutral anchor point was

used to measure the variables. In Table 1 is

presented the feedback questionnaire for the case

study (adapted from Venkatesh et al., 2003).

During the field trial, the Mora mobile service

gathered 67 registered users and the survey resulted

in 52 completed feedback forms. The results were

treated and analysed anonymously (Ervasti, 2007).

The analysis of the research data was done by using

SPSS 14.0 software. A small number of

questionnaire forms were incompletely filled in and

the answers were ambiguous in some places. The

ambiguity was resolved by interpreting the answer in

the least favourable way for the question presented.

The rather small amount of sample data restricted

the number of feasible analysis methods. The

analysis was conducted using the basic frequency

and descriptive calculations. The regression analysis

was utilised by first examining the effect of the

independent variables on the dependent variables

according to the set hypotheses, and then testing the

combined effect of the explanatory variables as

stated in the conceptual model.

Of the respondents, 11.5% were female and

88.5% male and the majority were less than 25 years

old. By nationality, 69.2% of the sample were

Finnish and 30.8% foreign; the foreign respondents’

nationalities mostly representing Nigeria, Russia and

Hungary. Most of the survey respondents had a

monthly income of less than 1,000 euros and a

relatively new mobile phone in use, the handset’s

age being under two years for the majority. The

sample’s monthly mobile phone expenditure was

mainly under 30 euros, and most used their phone

more for private than business purposes.

The survey respondents’ attitudinal valuations of

the Mora mobile service are presented in Table 1

with mean values and standard deviations. In

perceived usefulness, the respondents mostly agreed

with the statement “Using Mora gives me topical

information”. In perceived ease of use, most agreed

with the statement “I quickly learned to use Mora”,

and they were also aware of the kind of mobile

services they can use with their mobile phones. Most

users agreed with the statement that Mora

downloading and installation was easy. Users

disagreed with the statements concerning perceived

barriers to use. Fear of technical features, required

effort in downloading and installing the application,

or even the data transmission billing weren’t seen as

obstacles in adopting mobile services. The utilisation

of time and date-related contextual information in

Mora services was seen as more useful than the

utilisation of location-specific information. The

respondents weren’t especially eager to spend time

providing their personal details to make the content

in Mora more relevant to their needs.

When examining the perceived behavioural

control, the respondents found it important that they

could control the use of Mora by deciding when and

where to use the service. The reference group

influence was perceived as rather irrelevant in this

survey. The attitudinal construct showed that the

respondents had a more preferable attitude toward

downloadable applications than toward SMS-based

mobile services. Most agreed with the statement

“Using the mobile phone as a channel to access the

content of school intra is a good idea”. The

respondents reported that they were willing to use

Table 1: Feedback questionnaire items and attitudinal dimensions of test-user responses to Mora mobile service.

Construct item Variable Mean s.d.

Perceived usefulness

PU1 Using Mora gives me topical information. 4.29 0.610

PU2 Using Mora saves me time / helps me accomplish things more

quickly.

3.77 1.022

PU3 Using Mora gives me personal information. 3.39 1.150

PU4 Using Mora gives me information that is of interest to me. 3.81 0.817

PU5 I find Mora useful in my daily life 3.90 1.053

Perceived ease of use

PEOU1 I know what kind of mobile services I can use with my phone. 4.14 1.167

ADOPTION OF MOBILE SERVICES IN FINLAND - Conceptual Model and Application-based Case Study

135

Table 1: Feedback questionnaire items and attitudinal dimensions of test-user responses to Mora mobile service (cont.).

PEOU2 It was easy for me to download and install Mora in my mobile

phone.

3.88 1.211

PEOU3 I quickly learned to use Mora. 4.62 0.718

PEOU4 I find Mora easy to use. 4.33 0.964

PEOU5 My interaction with Mora is clear and understandable. 4.00 1.085

PEOU6 I find it easy to get Mora to do what I want to do. 3.92 1.100

Barriers to use

BU1 Fear of technical features is an obstacle to me adopting mobile

services.

1.63 1.085

BU2 Difficulty and effort caused by the downloading and installation of

the application in a mobile phone is an obstacle to me adopting

mobile services.

1.76 1.205

BU3 Knowledge of data transmission billing is an obstacle to me

adopting mobile services.

2.51 1.528

Context

CON1 I would view the content of Mora related to a specific time or date

(e.g. exam day, weekend) as useful.

4,39 0.750

CON2 I would view the content of Mora related to me being in a specific

location (e.g. campus restaurant, library) as useful.

4.10 0.953

CON3 I would be prepared to spend time providing my personal details (a

user profile) to make the content of Mora more relevant to my

needs.

3.78 1.112

Perceived behavioural control

PBC1 I find it important that I can choose between different styles in

Mora.

3.17 1.354

PBC2 I find it important that I can easily control the use of Mora (that I

can decide when and where I use Mora).

4.50 0.828

PBC3 I find it important that I can easily stop using Mora. 4.44 0.978

PBC4 It would be important for me to be in control in terms of the ability

to filter the content of Mora related to my interests/needs.

4.19 0.793

Reference group influence

REF1 I started to use Mora because it was recommended to me by

someone I know.

2.71 1.576

REF2 I started to use Mora because my friends are using it. 2.12 1.199

REF3 I would have been more likely to start to use Mora if the message

containing a link for downloading the application was forwarded to

me by someone I know.

2.83 1.424

REF4 I recommended Mora to people I know. 3.49 1.271

Attitude

ATT1 Using mobile services (downloadable applications) is pleasant. 3.90 1.159

ATT2 Using Mora is pleasant. 4.08 0.710

ATT3 Using mobile services (SMS-based) is pleasant. 3.38 1.223

ATT4 Using mobile technology to access a variety of services is

interesting.

4.31 0.707

ATT5 Using the mobile phone as a channel to access the content of the

university intranet is a good idea.

4.73 0.528

Intention

INT1 I feel positively about Mora. 4.54 0.503

INT2 I am willing to use Mora in the future, if possible. 4.48 0.641

INT3 I would use Mora regularly in the future. 4.02 1.038

Actual use

USE1 I am using Mora every day. 2.58 1.226

USE2 I am using Mora every week. 3.71 1.226

USE3 I regularly check what’s new with Mora. 3.40 1.302

ICE-B 2008 - International Conference on e-Business

136

Mora in the future. However, the actual use of Mora

wasn’t that regular since it happened more on a

weekly than daily basis.

71.2% of respondents reported having used other

mobile services in addition to Mora and 67.3% of

them had used downloadable applications, whereas

only 38.5% SMS-based services. 57.7% of

respondents reported having used entertainment

services, and 55.8% had used both the information

and news services and email; 38.5% had used instant

messaging, and 23% banking and financial services.

17.3% of respondents had experience of VoIP,

11.5% of ticket reservation, 7.7% of shopping, and

5.8% of travel booking.

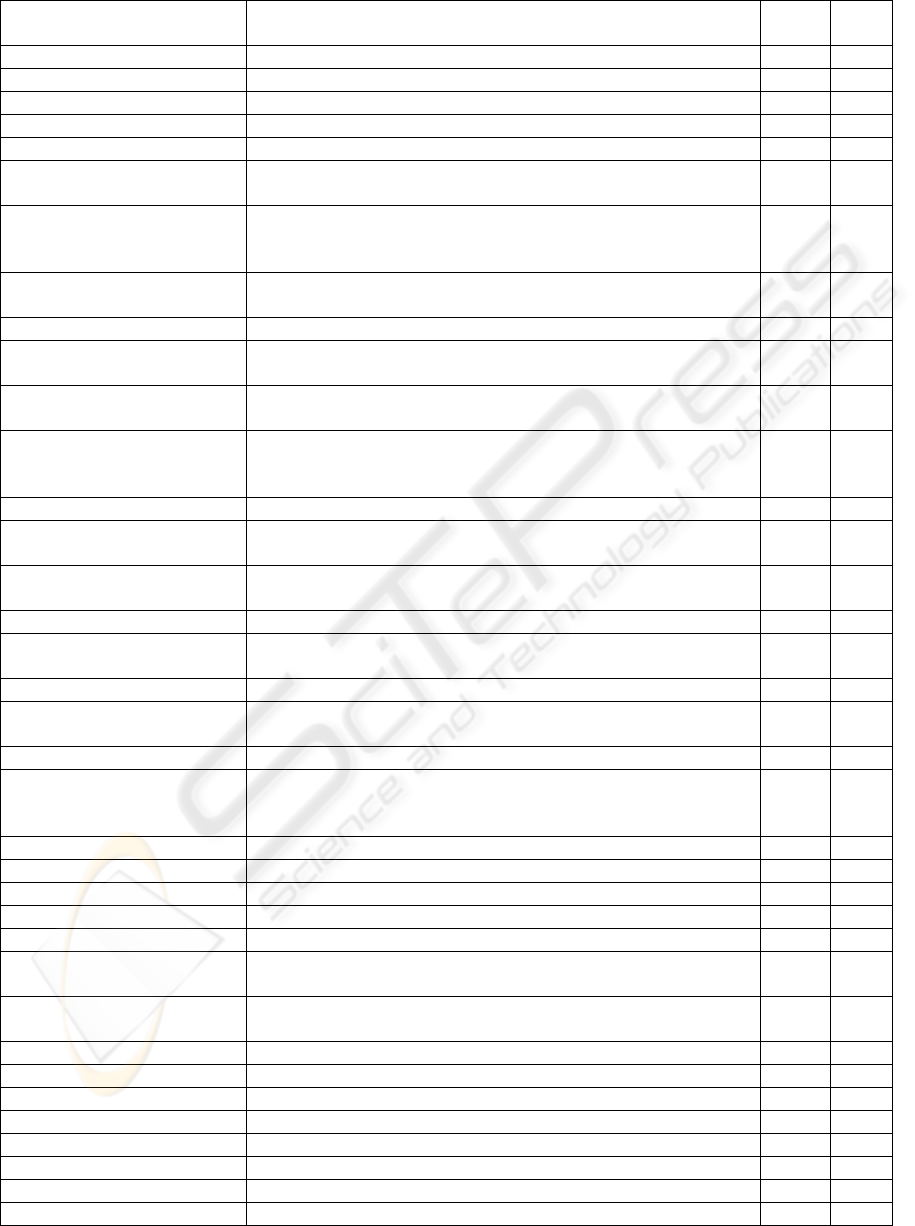

Table 2 shows the standardised coefficients and

t-values of the tested hypotheses regarding mobile

services (t-statistics indicating the significance of

individual variables when the t-value is > 2

(Schwager, 1995).

Table 2: Hypotheses examination.

Hypothesis Standardized

Coefficient β

t-

value

Sig.

H1: PU to ATT .419 3.164 .003

H2: PEOU to ATT .303 2.182 .034

H3a: BU to ATT -.173 -1.205 .234

H3b: BU to INT -.050 -0.345 .731

H4: CON to INT .539 4.430 .000

H5: PBC to INT .250 1.828 .073

H6: REF to INT .237 1.707 .094

H7: ATT to INT .572 4.882 .000

H8: INT to USE .381 2.913 .005

The strong coefficient of H1 shows that there is a

positive and direct relationship between PU and

ATT. Thus, the perceived usefulness of mobile

services is a strong predictor of attitude and H1 was

supported. It can also be seen that the PEOU of

mobile services was directly and positively

associated with ATT, providing support for H2. H3a

and H3b address the role of BU, the coefficients

were negative, but very low, which indicates that

barriers to use have no significant influence on

either attitude or intention, thus H3a and H3b were

not supported. Next, the strong coefficient of H4

indicates that context-related information acts as a

strong and positive predictor of intention to use

mobile services, so H4 was supported. H5 and H6

hypothesise that PBC and REF have a positive and

direct relationship with INT. Both coefficients are

similar with low magnitudes, therefore neither H5

nor H6 were supported by the data. H7 states that the

more favourable attitude a person forms toward

mobile services, the higher his or her intention to use

those services. The relationship was found to be

positive and statistically significant. The final

hypothesis, H8, argues that INT is directly

associated with USE, and the coefficient is strong

and positive. Thus both H7 and H8 were supported.

Figure 3 illustrates the standardised coefficients

for the conceptual model.

Figure 3: Conceptual model results.

During the field trial it was noticed that mobility

does not provide enough added value for the users

when the Mora service is in its current form.

Consumers were not attracted to the service because

they already had an easy and familiar way to access

almost the same content via the web, so they felt that

the Mora is just a mobile substitute for the campus’

web intranet. Even though the challenges with

marketing the Mora service and establishing test-

users’ interest were recognised and actions were

taken to overcome them, one reason for the

somewhat modest use of the Mora service was that

the benefits of the service weren’t enough visible to

potential adopters. For Mora service users, the

easiness and flexibility of the service should have

been stressed even more, i.e. that service can be used

at any time and in any place, freeing the users from

the traditional time and place constraints even more

efficiently than Internet services. Another significant

obstacle was the effort required in downloading and

installing the application. To diminish this problem

several separate events were arranged where

guidance and support in service adoption was

offered to users.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This paper introduces a conceptual model for mobile

service adoption that is a modified version of

established adoption models. The developed

conceptual model was evaluated and validated in the

ADOPTION OF MOBILE SERVICES IN FINLAND - Conceptual Model and Application-based Case Study

137

real-life case study of mobile service, through which

we have gained practical insights into application-

based mobile service development and promotion, as

well as having identified the factors affecting the

adoption of mobile services in Finland.

The findings from the survey suggest that

perceived usefulness of mobile services is the

strongest predictor of attitude toward mobile

services. That is also supported by previous studies

(e.g. Rogers, 1995) on consumer acceptance of new

technologies. People will adopt a technology when

the added value offered by technology fulfils their

needs. Hence, compatibility with users’ needs (ibid)

is a critical variable for predicting technology

adoption. Ease of use wasn’t perceived as having a

strong relationship with acceptance of mobile

services, contrary to (ibid), so it can be reasoned that

usefulness is a stronger determinant of attitude

toward mobile services than perceived ease of use.

Utilisation of contextual information was found to

have a strong impact on intention to use mobile

services and proves that consumers desire relevant

and personalised services.

The respondents did not perceive the technical

features of mobile services, the downloading and

installation process or data transmission billing as

significant barriers to adopting mobile services as

prior researches suggest (Aarnio et al., 2002; Nokia,

2003). When examining the impact of control and

social norms, the results of the survey were not

congruent with the theoretical background (Ajzen,

1991; Rogers, 1995) either, since perceived

behavioural control and reference group influence

weren’t stated as important determinants of service

adoption. A preferable attitude toward mobile

services was however proved to have a strong

impact on intention to adopt services, whereas the

intention in the end didn’t act as a good predictor of

actual use.

Based on the case study findings, it is suggested

that the extended and modified conceptual model

can be used to guide industry players’ evaluation of

the adoption potential of new mobile services. Case

study results can be used to help mobile service

providers choose right development and marketing

strategies for mobile services and accelerate the

diffusion of services. However, further and more

extensive studies should be conducted in order to

attain a more profound understanding of the issues

concerning consumers’ drivers for adopting (or

rejecting) mobile services. Similar research need to

be done in other countries as well in order to obtain

benchmarks for comparing the differences in

adoption characteristics in different countries, and to

further validate the conceptual model. In an

international comparison, Finland is an advanced

information society especially when it comes to

mobile communication. Thus, the study findings

might vary in other countries with far lower mobile

phone penetration rates and different mobile

communication culture. However, when compared

to Japan, Finland is far behind in the versatility of

mobile communication: in Japan, a nation of 127

million the number of mobile internet subscribers

recently passed 100 million (The Guardian, 2007).

The conceptual model should also be extended

further to include more factors that reflect the unique

characteristics of the usage intentions of mobile

services. Further attention should be devoted to the

comparison of rival models in explaining consumer

attitudes and intentions.

REFERENCES

Aarnio, A., Enkenberg, A., Heikkilä, J., Hirvola, S., 2002.

Adoption and Use of Mobile Services: Empirical

Evidence from a Finnish Survey. In Proceedings of the

35th Hawaii International Conference on System

Sciences, 3(35), pp. 1454-1463. IEEE Computer

Society.

Ajzen, I., 1991. The theory of planned behaviour.

Organisational Behavior and Human Decision

Processes, 50(2), pp. 179-211. Elsevier.

Alahuhta, P., Helaakoski, H., Smirnov, A., 2005.

Adoption of Mobile Services in mCommerce –

Technologies and Success Factors. In IEEE ICEBE

2005, pp. 531-534.

Anckar, B., 2002. Motivators for Adoption of Mobile

Commerce: Findings from a National Consumer

Survey. In Proceedings of the International

Conference on Decision Making and Decision Support

in the Internet Age (DSIage 2002), pp. 749-762.

Bouwman, H., Carlsson, C., Molina-Castillo, F.J.,

Walden, P., 2007. Barriers and drivers in the adoption

of current and future mobile services in Finland.

Telematics and Informatics, 24(2), pp. 145–160.

Elsevier.

Cheong, J.H., Park, M., 2005. Mobile internet acceptance

in Korea. Internet Research, 15(2), pp. 125-140.

Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Davis, F.D., 1989. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease

of Use, and User Acceptance of Information

Technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), pp. 319-340.

Management Information Systems Research Center,

University of Minnesota.

Davis, F.D., Bagozzi, R.P., Warshaw, P.R., 1992.

Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivation to Use Computers

in the Workplace. Journal of Applied Social

Psychology, 22(14), pp. 1111-1132. Blackwell

Publishing.

ICE-B 2008 - International Conference on e-Business

138

Ervasti, M.A., 2007. The Development of Mobile Service

Concepts – Technologies, Adoption and Use,

University of Oulu, Department of Electrical and

Information Engineering. Master’s Thesis, Finland.

Figge, S., 2004. Situation-dependent services – a

challenge for mobile network operators. Journal of

Business Research, 57(12), pp. 1416-1422. Elsevier.

Fishbein, M., Ajzen, I., 1975. Belief, Attitude, Intention

and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and

Research, Addison-Wesley. Reading, MA.

Gilbert, A.L., Han, H., 2005. Understanding mobile data

services adoption: Demography, attitudes or needs?

Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 72(3),

pp. 327-337. Elsevier.

Gillick, K., Vanderhoof, R., 2000. Mobile E-commerce:

Marketplace Enablers and Inhibitors. In Smart Card

Forum Annual Meeting, 23 p.

The Guardian, 2007. Why mobile Japan leads the world.

Accessed 03.06.2008. URL:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/technology/2007/sep/27/gu

ardianweeklytechnologysection.mobilephones

Hyvönen, K., Repo, P., 2005. Mobiilipalvelut

suomalaisten arjessa (Mobile services in the every day

life of Finns). In Vox consumptoris – Kuluttajan ääni,

pp. 41-59. National Consumer Research Centre,

Helsinki. (In Finnish)

Invest in Finland, 2008. Top 56 mobile phones in Finland

were all made by Nokia. Accessed 03.06.2008. URL:

http://www.investinfinland.fi/news/2008/en_GB/nokia

/

It-viikko, 2007. Every fourth Finn surfs on their mobile

phone (In Finnish). Accessed 03.06.2008. URL:

http://www.itviikko.fi/talous/2007/01/23/neljannes-

suomalaisista-surffaa-kannykalla/20071827/7

Kaasinen, E., 2005. User acceptance of mobile services –

value, ease of use, trust and ease of adoption, VTT

Publications 2005. Espoo.

Karjaluoto, H., Alatalo, T., 2007. Consumers’ attitudes

towards and intention to participate in mobile

marketing. International Journal of Services

Technology and Management, 8(2/3), pp. 155-173.

Inderscience.

Moore, G.A., McKenna, R., 1999. Crossing the Chasm:

Marketing and Selling High-Tech Products to

Mainstream Customers, Harper Business. New York.

Moore, G.C., Benbasat, I., 1991. Development of an

Instrument to Measure the Perceptions of Adopting an

Information Technology Innovation. Information

Systems Research, 2(3), pp. 192-222. INFORMS.

Muller-Veerse, F., 2000. Mobile Commerce Report,

Durlacher Research Ltd. London.

Nokia, 2003. Java™ technology enables exciting

downloading services for mobile users. In White

paper. Nokia Corporation, Finland.

Rogers, E.M., 1995. Diffusion of innovations, Free Press.

New York, 4th edition.

Schwager, J.D., 1995. Fundamental Analysis, John Wiley

and Sons. United States.

Statistics Finland, 2007. From hand-cranked connections

to hands-free mobile calls – history of

telecommunications in Finland seen through statistics.

Accessed 03.06.2008. URL:

http://www.stat.fi/tup/suomi90/syyskuu_en.html

Taylor, S., Todd, P.A., 1995. Assessing IT Usage: The

Role of Prior Experience. MIS Quarterly, 19(2), pp.

561-570. Management Information Systems Research

Center, University of Minnesota.

Thompson, R.L., Higgins, C.A., Howell, J.M., 1991.

Personal Computing: Toward a Conceptual Model of

Utilization. MIS Quarterly, 15(1), pp. 124-143.

Management Information Systems Research Center,

University of Minnesota.

Venkatesh, V., Davis, F.D., 2000. A Theoretical Extension

of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four

Longitudinal Field Studies. Management Science,

46(2), pp. 186-204. INFORMS.

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M.G., Davis, G.B., Davis, F.D.,

2003. User Acceptance of Information Technology:

Toward a Unified View. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), pp.

425-478. Management Information Systems Research

Center, University of Minnesota

ADOPTION OF MOBILE SERVICES IN FINLAND - Conceptual Model and Application-based Case Study

139