ENHANCING THE BLENDED SHOPPING CONCEPT WITH

ADDITIVE MANUFACTURING TECHNOLOGIES

Added Value for Customers, Retailers and Additive Manufacturers

Britta Fuchs, Thomas Ritz and Henriette Stykow

Department of Electrical Engineering and Information Technology, FH Aachen, Eupener Str. 70, 52070 Aachen, Germany

Keywords: Blended Shopping, Mass Customization, Additive Manufacturing, eCommerce, Retail, Toolkit, Customer

Experience, Distributed Manufacture.

Abstract: This paper starts from the idea that combining processes of eCommerce and traditional commerce (blended

shopping) can bring advantages for customers and retailer. One possibility to take the emerged

individualization trend on consumer markets into account is to integrate latest rapid prototyping

technologies (additive manufacturing) in order to enhance the blended shopping concept. The availability of

Internet can be seen as the enabler for such services. First blended shopping and rapid prototyping with its

latest developments of additive manufacturing (AM) are explained. Then their impacts on the aimed

individualized blended shopping concept are depicted with the help of a use case. From this use case the

benefits for business and consumers are derived and additionally the framework of a needed AM-toolkit is

concretized. Finally the paper closes with a future outlook on the necessity of research in the field of

individualization aspects of blended shopping and web standards.

1 INTRODUCTION

Fundamental changes have occurred in the last years

regarding the shopping behavior of consumers, who

nowadays organize their purchase over different

distribution channels.

The idea of blended shopping (Fuchs and Ritz,

2009) is to overcome the borders of traditional retail

and eCommerce in order to deliver increased value

to customer and merchant. Integrating eCommerce

services into a brick-and-mortar-shop demands for

interactive systems (such as web-enabled kiosk

terminals or mobile devices). Internet is the enabler

of blended shopping concepts, facilitates the

shopping processes and drives customer experience.

Customer experience is known to tremendously

shape the overall shopping engagement of the

individual.

Shopping as the goal-directed process of buying

a product not only depends on the utilitarian value

that is being proposed, but also on hedonic values.

Buying customized products has a high impact on

the hedonic value at usually high costs. A way to

offer customized products at (almost) mass product

prizes is mass customization (MC). It may now

experience another raise of importance with the

advent of additive manufacturing technologies

(AM). These enable an extent of freedom of creation

that was recently unknown and are mainly used by

industry to produce prototypes or small batches.

Now customized products produced by AM

technology are ready to be offered to consumers as

well.

To take the individualization trend into account

this paper addresses the enhancement of the blended

shopping concept by integrating latest customization

possibilities (AM). The ideas of blended shopping

and MC with AM are explained in chapter 2. The

possibilities and challenges for customer, merchants

and AM producers are presented in chapter 3. In this

scenario data flows and processes have to be

reengineered determined e.g. by the fact that non-

specialists (customers) have to communicate with

technicians (AM producers). A future outlook is

given in chapter 4.

2 SHOPPING AND PRODUCTION

APPROACHES

In this chapter the basic aspects of blended

492

Fuchs B., Ritz T. and Stykow H..

ENHANCING THE BLENDED SHOPPING CONCEPT WITH ADDITIVE MANUFACTURING TECHNOLOGIES - Added Value for Customers, Retailers

and Additive Manufacturers.

DOI: 10.5220/0003933704920501

In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (WEBIST-2012), pages 492-501

ISBN: 978-989-8565-08-2

Copyright

c

2012 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

shopping, mass customization and additive

manufacturing are explained. This introduces to the

extension of the blended shopping concept with

customization in chapter 3.

2.1 Blended Shopping

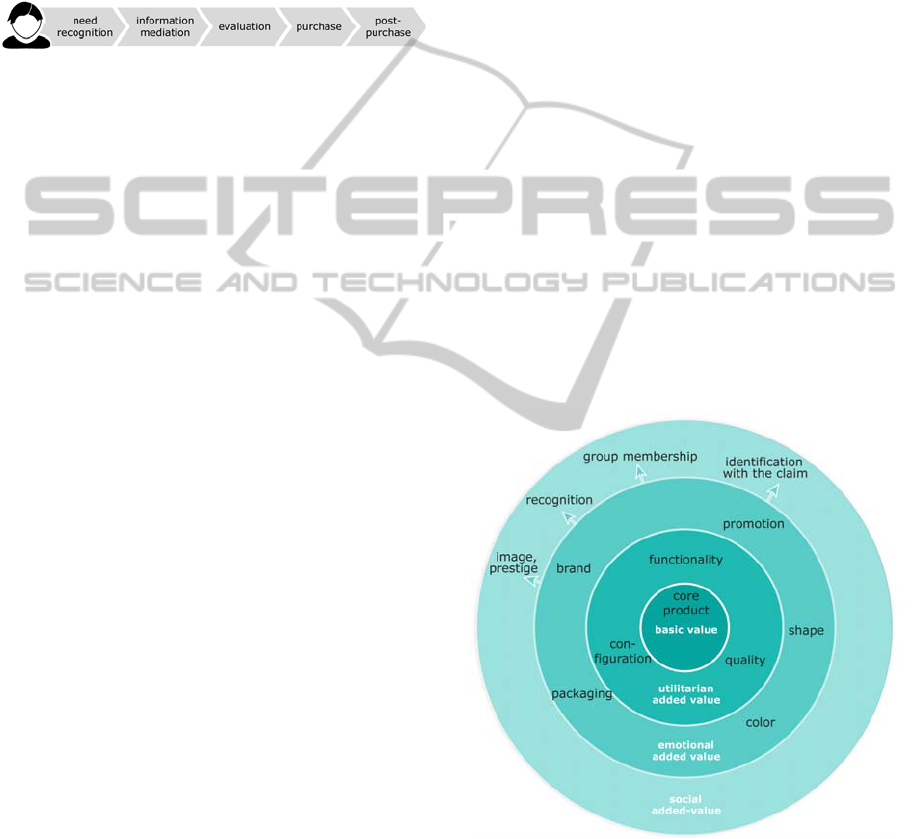

When making a purchase decision, customers pass

several phases (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Customer decision process.

After recognizing a certain need or shortage of

something, they start searching for solutions. The

information mediation phase and the evaluation of

its outcome are critical for the purchase decision

regarding what product to buy and where (to what

price) to buy it. The conditions under which a

decision is taken also influence the perceived

satisfaction during later usage. The internet has

impacted shopping behaviors significantly. The

growth of information technology and its ubiquity

has strengthened the power of the customer. Not

only does he have easy access to domain knowledge,

price comparisons and user reviews on products but

also the opportunity to influence the rise and fall of

products and brands. Customers identified ways to

combine advantages of the traditional retail channel

with those of eCommerce: They might gather

information online and buy the product in a brick-

and-mortar-shop or vice versa, depending on the

type of product (Grewal et al., 2009); (van Baal and

Hudetz, 2008).

The concept of blended shopping expresses the

combination of both traditional retail and

eCommerce processes (Fuchs and Ritz, 2011).

Integrating eCommerce facilities into a brick-and-

mortar-shop could help the merchant to keep

turnover within the trade chain by satisfying

customers. Nevertheless many retailers still fear the

power of information technologies. Implementations

of interactive prototypes have depicted opportunities

of how to take advantage on the retail environment

(Fuchs and Ritz, 2011). Delivering information in a

relevant context proved to enhance the way the

customer navigates and understands the information.

This idea is not new – self-service technologies like

in-store information terminals or bar code scanners

are common retail practice for years. They provide

extensive product selections and powerful search

tools. For online shops offering this exact benefit it

becomes increasingly popular to gather the

interaction data of the user (e.g. which

products/features a customer was interested in,

which topics he explored how long, etc.). The

blended shopping scenario aims to gather that

information within the retail channel, which makes

its purposeful utilization more likely.

2.2 Customer Experience

The integration of interactive systems, such as

terminals or mobile devices by its nature adds

another aspect to the retail environment.

Multimedia-driven experience is one effective

means to shape a compelling customer experience

and a presumption to deal with the integration of

individualized products into the value chain.

Even though shopping is a purposeful activity, it

is not only and sometimes not even the goal to

acquire a product. Besides the specific need for a

product (utilitarian motivation), the wish for social

interaction, entertainment, recreation or intellectual

stimulation (hedonic motivations) might encourage

shopping (Arnold and Reynolds, 2003). These

aspects comprise emotional and social values

(Kotler et al., 2007); (Meffert and Burmann, 2008)

that add to the utilitarian value (see figure 2). They

impact the purchase decision.

Figure 2: Overall value of a product.

Puccinelli et al. (2009) suggest that goals,

schema, information processing, memory,

involvement, attitudes, affect, atmospherics,

consumer attributions and choices critically

influence the shopping behavior.

ENHANCINGTHEBLENDEDSHOPPINGCONCEPTWITHADDITIVEMANUFACTURINGTECHNOLOGIES-

AddedValueforCustomers,RetailersandAdditiveManufacturers

493

While the influence from these elements differs

according to the phase of the decision process, all of

these are relevant for the evaluation phase.

Understanding these influences on the customer is a

precondition to enhance retail performance and thus

increase customer satisfaction and loyalty. They

impact the cognitive, affective, emotional, social and

physical responses to the retailer (Verhoef et al.,

2009). Despite the fact that he cannot control the

bespoken aspects, there are further facts that add to

the overall picture of a retail experience. These

include e.g. shop atmosphere, store layout,

assortment and prices. They all built up to what is

called customer experience. It is defined as “the

internal and subjective response customers have to

any direct or indirect contact with a company. Direct

contact generally occurs in the course of purchase,

use, and service and is usually initiated by the

customer. Indirect contact most often involves

unplanned encounters with representatives of a

company’s products, service or brands and takes the

form of word-of-mouth recommendations or

criticisms, advertising, news reports, reviews and so

forth” (Meyer and Schwager, 2007, p. 117).

Heading for a customer-oriented strategy,

retailers have to actively enrich the customer

experience by addressing the previously mentioned

aspects. It was argued that this has to take place in

accordance to the customer’s needs and objectives.

These critical retail drivers are so various because

they are unique to every customer. Consequently,

they are better understood the more a retailer knows

about the individual. One way to approach this goal

is to integrate the customer into retail experience or

even value creation like extending blended shopping

with individualization aspects.

2.3 Mass Customization

Blended shopping and the creation of customer

experience have the customer-centric approach in

common. It is that same idea that mass

customization originated in. Coined in 1987 by

Davis (Davis, 1987) and later refined by Pine (Pine,

1993) it means “developing, producing, marketing

and delivering affordable goods and services with

enough variety and customization that nearly

everyone finds exactly what they want” (p.44).

Once meant to meet the requirements and needs

of the individual customer MC until today did not

gain the market share one, with good cause, would

have it credited to. The idea of providing the

customer with an individualized product or service

that better suits his individual preferences than any

standard product is a goal, which enjoys more right

to exist than ever before.

Several facets lend themselves to distinguish

types of mass customization (Duray et al., 2000);

(Gilmore and Pine, 1997); (Piller and Stotko, 2002).

The most basic delineation expresses who is in

charge of transforming the customization

information into a product specification. In this

sense passive MC means that the transformation is

executed by the operator, whereas active MC assigns

this task to the customer.

The idea behind mass customization is basically

highly emotional: By customizing a mass product

the customer is caught at his most profound desires

and needs which derive from his personality, life-

style, self-perception and preferences. Blending

these attributes into a standard mass product

becomes more promising and at the same time

challenging when this task is achieved by the

customer itself (active MC). In the latter case, the

customer finds himself in the position of a co-

creator. He is ought to choose from a pre-defined set

of parameters and alternatives. This co-creation-

phase specifies the individual product.

The fact that preference information is known to

be sticky, which means that it is difficult to be

transferred from customer to supplier, militates in

favor of this form of active mass customization. It is

standard practice to enhance the information

elicitation with an interactive system (so-called

configurator or toolkit) (Piller, 2004).

2.4 Additive Manufacturing

The manufacturing industry for hundreds of years

has applied formative (e.g. pottery) or subtractive

(e.g. laser cutting) techniques in order to produce

goods. Recently, additive manufacturing (AM),

commonly known as 3D-printing, has evolved. It

describes the arrangement of material layers that

finally built up to the object. The geometrical

information for each slice is being derived from a

CAD volume-model. It defines the object’s inner

and outer shape. In order to build it, the model is

virtually being sliced into fine layers. This contour

information is given to the AM machine, which then

generates the object (Gebhardt, 2004). The different

AM technologies differ in terms of the way the

layers are generated (gluing, melting, extruding), the

materials they are able to process and the way the

layers are connected. Either way, the physical and

mechanical properties of the object are defined by

the chosen material.

WEBIST2012-8thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

494

AM allows for a range of design possibilities that

was unknown until today. Since the product is built

up layer by layer, this allows for new approaches on

the product design such as:

definition of the inner structure (impacts e.g.

weight and stability)

complexity (e.g. holes, arching, warps,

interweavement)

integrated functional elements (e.g. hinges)

parts consolidation (multiple elements may be

manufactured as one)

Leaving behind traditional design restrictions in

terms of undercuts, draft angles, weld lines,

avoidance of sharp corners and uniform wall

thickness considerations, this offers real design

freedom (Hopkinson et al., 2006). However, some

considerations on wall thickness and resolution (that

is the height on the individual layers) and material

are required. They depend on the chosen technology.

Today’s variety of applications of AM shows its

opportunities. Besides aerospace and industry

branches like automotive it establishes on markets

where highly individual products are needed. These

include dental applications, hearing aids and

prostheses. It is furthermore emerging in jewelry

industry. With the coverage of further materials, AM

will become more relevant for other industries as

well (Gebhardt, 2007).

3 USE CASE: SHOE SOLE

CUSTOMIZATION

The almost unconstrained design freedom favors

additive manufacturing for mass customization with

blended shopping. It even pushes the boundaries of

what MC is known today. While existing MC-

approaches mostly offer the configuration of pre-

defined parameter values, MC with AM permits an

unconstrained solution space. This lives up to what

customization is meant to be.

This chapter ponders that potential application in

the field of shoe customization in a traditional brick-

and-mortar shop: the customization of the outsole of

a shoe. It demonstrates the benefits for potential

parties involved. Main facets grow from the creation

of a customer experience.

3.1 Concept Legitimation

The authors developed a concept for the

customization of the outsole of a shoe. AM allows to

not only modify the design in terms of color or

materials. The customer can create his very personal

footprint by also designing the patterns of the

outsole. Additionally it allows adding functional

elements such as spikes or heels. This customization

is enabled through a kiosk-system that runs the

product-specific application (toolkit).

Researchers and suppliers have identified the

footwear segment as a suitable use case for offering

individualization services. NikeID, Adidias Mi, and

Selve just name a few of available offerings today.

Apart from design choices, research has also

addressed how to automate production processes to

individualize the fit of a shoe. Proofs of concept

have already been achieved for the use of additive

manufacturing (Dietrich et al., 2007); (Peels, 2010).

The cross-channel behavior of consumers in the

footwear market shows, that 50% of the purchases

that are fulfilled via online sales happened to have

started in the traditional retail (van Baal and Hudetz,

2008). This makes it an ideal field for applying

blended shopping strategies. Innovating the retails’

purchase offers is a good means of differentiating

from competitors as shoe merchants are noticeable

conservative (Theis, 2006). The intention to offer

MC-service for a retailer might be to enhance his

service and performance in order to offer benefit to

the customer. By that, he could increase loyalty and

retention and create a new image to differentiate

from competition.

3.2 Business Benefits

The retail ties in basic value creation activities of

other parties – namely the manufacturer of the shoe,

the additive manufacturing provider and the

customer. The individual benefits of these actors

depend on the chosen operator model. It also

impacts questions on copyright and data ownership.

Figure 3: Values for involved parties.

ENHANCINGTHEBLENDEDSHOPPINGCONCEPTWITHADDITIVEMANUFACTURINGTECHNOLOGIES-

AddedValueforCustomers,RetailersandAdditiveManufacturers

495

The shoe manufacturer gives the shoes to the

retailer. Ideally and due to the fact that a sole has to

be assembled to the shoe, these shoes leave the

manufacturers facilities before the native sole is

attached. The additive manufacturers would let the

retailer rent AM annexes, so that they could be

placed inside the store for attraction purposes. The

customer invests time, effort and money and leaves

interaction data as well as a certain amount of

personal data (e.g. address, name). The retail in

return delivers value to these parties (see figure 3).

The manufacturer will profit essentially from the

integration of the customer. It could be particularly

interesting to recognize, what the customers use the

shoe for. As the ability of the customer to directly

manipulate a product that once a huge brand and

manufacturer was in charge of, this integration

means a shift to democratizing the way products are

created. The manufacturer would have a stake in this

as this provides an immediate access to customer

needs and innovation ideas. He could react on this

with changes on his assortment. Moreover such an

approach offers valuable differentiation aspects from

competition.

The scenario opens a new market for the additive

manufacturer. It also benefits from the predictability

of the production needs. As he is mainly involved in

industrial projects, where requirements differ hourly,

this makes a difference: after initial requirements

engineering it will become a routine and a self-up-

keeping source of revenue. Entering new markets

and addressing new target groups means as well a

growing independence of AM producers from large

scale industry.

The retail itself gains insights into evolving

needs and trends of its customers. This could be

transformed into better marketing and advice but

should also be used to improve the creation of a

compelling customer experience.

3.3 Customer Benefits

The benefits for the customer are twofold. Merle et

al. (2010) allocate the values from the customer

perspective to co-design on the one side and product

value on the other (compare table 1). While

utilitarian, uniqueness and self-expressiveness value

are defined as product-related, hedonic and creative

achievement value are assigned to the co-creation-

process. Following it will be argued that all values

are determined in both co-creation and product

experience.

Utilitarian value is related to the product’s fit to

individual requirements (Dellaert and Dabholkar,

2009). It rises when the customized product provides

higher values than any standard product (Tseng and

Jiao, 2001). This is achieved through the fit of style,

function and physical fit (Piller, 2004). Moreover,

the co-creation itself increases the utilitarian benefit.

As the customer has to explore the solution space, he

dives deeper into the subject. Not only does this

convey information on the domain (of shoes and

potential key value attributes) but also does it

stimulate reflections on his needs. This facilitates the

customization decisions.

Apart from that, psychological effects need to be

considered. They consist in the symbolic meaning of

the products uniqueness. Autonomy and uniqueness

rise from the range of the solution space. Studies of

Sinclair and Campbell (2009) revealed that

customers doubt that no other would have made the

exact changes to a pre-existing model that they

carried out. For the design for AM, the uniqueness

value is highly increased due to the freedom of

creation.

Self-expression may be considered a life goal, so

to say a long-term desire and motivation that

justifies the end goal. Co-creation targets the self-

fulfillment and the creative engagement. Self-

expression describes also how the customer wants to

feel during the co-creation and may therefore be

considered as an experience goal. It mainly causes

that the customer perceives an increased quality of

the product after customization (Füller et al., 2011).

Competency, task and process enjoyment mainly

shape these emotions. The self-expressiveness value

of the final product helps the customer to

differentiate from other consumers. It is proposed

that this is motivated from counter-conformity

attempts (Tian et al., 2001). Creating value with

solutions for own needs and requirements increases

this self-congruity which results in higher

satisfaction. At the same time, customers tend to

choose products which reflect their self-perception

(status, taste, style) (Chang et al., 2009); (Chang and

Chen, 2009).

Emotions and mood impair the satisfaction

essentially (Jones, Reynolds, & Arnold, 2006). The

co-creation experience has a high impact on the

perceived value of the product and the underlying

end goals. The hedonic values are correlated with

the customer satisfaction with the product.

Additional value rises with the recognition and

admiration when the customized product is shown to

peers.

The creative achievement value may be

perceived as the fulfillment of a life goal. It is

related to the efforts the customer had to take. This

perception is influenced by both store and design

WEBIST2012-8thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

496

Table 1: Perceived benefits for the customer during and after customization process.

Co-creation Product usage

utilitarian value

explore options,

reflect on own requirements and needs,

understand domain-related correlations

aesthetic, functional fit, congruency

uniqueness value

motivator to take the efforts,

depends on the variety of options

better fit to personal unique situations than any

standard product

self-expressiveness

value

as an innovator, creator, designer

(life goals)

reflects attitude and self-perception

hedonic value

entertainment, quality time,

enjoyment, fun

more pleasant to use,

recognition and admiration of peers

creative achievement

value

accomplishment of creative task,

supported by small rewards along the way

pride-of-authorship

of the customization process (e.g. supported by

interactive media). Customers will be proud, if the

efforts are rewarded with surprisingly good

outcomes (Franke et al., 2008; Weiner, 1985). Pride-

of-authorship nurtures satisfaction with the product.

This affects the way the customer uses the product,

the feelings that are connected with it and the way

he presents it to others. These feelings are well

suited for positive-word-of-mouth advertising and

for viral marketing attempts.

3.4 Solution Space Development

In order to provide the biggest benefit for the

customer, the customization operator must identify

the key value attributes that on the one hand

influence the buying behavior and on the other

reflect in which the target group differs the most. In

the use case of this paper we assume that customers

base their purchase decisions on sole features

including e.g. style, impermeability, resistance to

slippage, flexibility, foot protection, breathability.

Six attributes sum up these requirements: color,

material, shape, inner structure of the sole, tread and

method of attaching the sole to the shoe.

The presented scenario focuses on offering color,

material, shape and tread as customizable features,

leaving behind those attributes that would not

considerably increase the perceived value for the

customer. These four dimensions cover modification

of quality, size, look, functionality and contribute to

additional service propositions such as unique

packaging and gimmicks. Thus it comprises all

kinds of values, which a product bundles.

3.5 Toolkit Development

3.5.1 Need for an AM-Toolkit

Pushing the boundaries of MC with AM, on the first

sight this sounds like a great achievement. The chal-

lenge behind is to on the one side make the solution

space accessible for the customer and on the other

make sure that the design freedom would not

overwhelm the him.

If unconstrained freedom shall be given to the

co-creation, how can the customer make use of it? It

has to be considered that he might lack in

professional skills of designing his product. Or even

earlier in the process, he might not even feel inspired

or creative enough to approach such a design task.

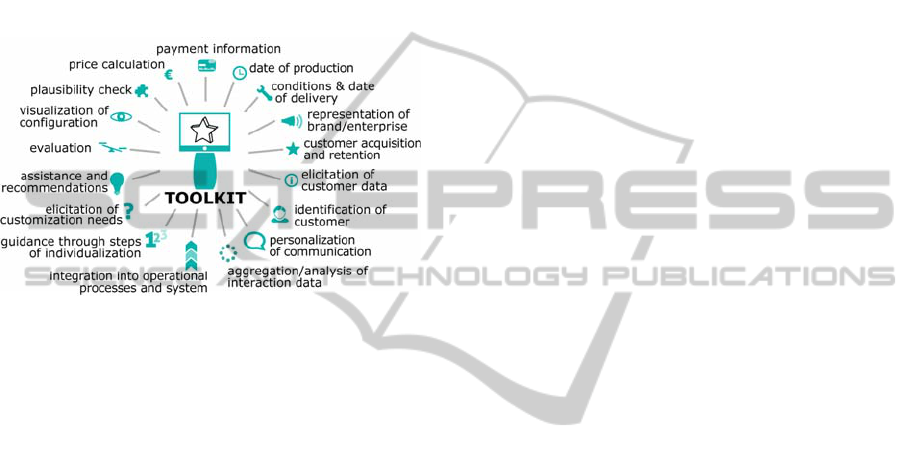

An interactive system, the toolkit, comes in

handy at that point. It acts on the interface between

customer and production. It enables the customer to

transform wishes and ideas into certain product

specifications or design (see figure 4). That is, he

reaches his end-goal of customizing the shoe. In the

peculiar context of AM, the toolkit would need to:

make the solution space accessible

provide easy to use design tools

inspire and entertain, in order to lower the

perceived effort for the customer

consider manufacturing issues (that is unstick the

supplier’s information for the customer)

organize the data-exchange with the AM

machine

enable the customer to fulfill the co-creation by

ordering the manufacture of his product.

The toolkit must communicate its potential for co-

creation. This effect has to take place in the need

recognition phase in order to stimulate the

customer’s desire for self-expression. The overall

intention must be communicated, the way of

interaction must attract people and potential

achievements must be presented since it may occur

that the customer does not foresee the concrete

outcome of his creation.

Generally, the customer will tackle the

customization with high involvement due to the fact

that he wants to realize his needs and ideas in order

to acquire a better fit than the available standard

product. As long as the toolkit does not deceive him,

ENHANCINGTHEBLENDEDSHOPPINGCONCEPTWITHADDITIVEMANUFACTURINGTECHNOLOGIES-

AddedValueforCustomers,RetailersandAdditiveManufacturers

497

he will be willing to invest time, engagement and

money. Research should collect data on where this

acceptance reaches its limits.

Moreover, the toolkit ties in the data of all parties

involved. This requires an integration of enterprise

specific applications, e.g. ERP- and CRM-systems.

The integration of social web and communities can

raise additional value. Depending on the product

category and the customization aim it could also

help to connect the toolkit to online databases of 3D-

models available for download.

Figure 4: Main responsibilities of the toolkit.

3.5.2 Implications on Interface Design

The interface design of the toolkit is a decisive

criterion for success. It essentially shapes the

experience. Its relevance for the creation of benefits

for the customer has been shown. This does account

for business goals as well: If the entertainment and

challenge by the co-creation-task are taken in

positively, even customers’ willingness to pay

higher prizes increases (Franke and Schreier, 2010);

(Merle et al., 2010). The modern interaction design

theory pays immense attention to the requirements

of users, users’ tasks and context of use.

Offering the co-creation as active MC has to deal

with the fact that the customer might lack in design-

related skills. Customers that engage in MC

activities have daily contact with web browsing, e-

mail, social networking, social messaging services,

Microsoft Office software as well as other

applications (Bauer, 2010); (Füller et al., 2011).

Even though that favors the technology readiness of

the customers, they still might perceive the efforts as

high transaction costs. Employees in the store can

eliminate that by supporting the customer.

Nonetheless, the system has to provide the customer

with design opportunities and ensure the

manufacturability.

Engaging AM as the production method

predetermines that a 3D-modell has to come out of

the design process. To enable the customer to make

use of the design freedom, intuitive interaction

approaches (e.g. using a touch screen) that facilitate

the design activities and support metaphors (e.g. of

formative manufacturing as it is known by the

customer) have to be considered. Engaging pleasant

and suitable metaphors and topics help to focus the

attention of the customer. Additionally they help rise

positive associations and positive feelings. Ideally

this leads to a linkage of compelling experiences

with the brand or store.

Furthermore, locating the toolkit in the retail

environment implies that noise, rush and light might

negatively impair the process and rob the customer’s

attention.

3.5.3 Permit Customization Actions

It is of major importance to guide the user through

specific customization possibilities, to inspire and

encourage him to pursue the process and to support

his design.

Concrete actions may stimulate the customer’s

involvement. Promotion, campaigns and claims

should seek to address the life goals of the customer

and emphasize the experience, which the

customization leverages. The issued appeals could

target the expression of personality, self-confidence

or even environmental consciousness (e.g. the AM

technology is power-saving compared to the

standard production). The decision in favor of any of

the proposed means must be based on the customer’s

attitudes and goals.

Employees, signage and toolkit have to introduce

the customer to the domain of customization and

present the solution space. It is important to

overcome doubts. In the given case, this means

primarily showing examples of customizations by

other clients. Related to that, an introduction to AM

would come in handy. As this technology is

probably not well known to the customer, it is

accompanied by a certain fascination and awakes his

curiosity. Even if this presentation does not lead into

co-creation, it will have stimulated that the customer

talks about it. Retail has the means to make the

customer experience the customization dimensions,

for example by touching material samples, testing a

customized sole or watching the production process

in a show-annex.

In order to lock-in the customer for the co-

creation phase, the toolkit has to engage the

customer to become creative. If his intrinsic

motivation already does so, the toolkit at least has to

keep him motivated. That is why the interaction with

WEBIST2012-8thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

498

the toolkit has to be easy. Ideally it is easier than the

customer would have thought after seeing the

customizations of others. Such a surprise could

finally convince the customer to try it out.

3.5.4 Choice Navigation

The toolkit needs to provide guidance to the

customer when navigating through the solution

space. This can be achieved by structuring the

process meaningful and conveying information

about the domain (e.g. with the help of third parties).

Necessary information must be delivered wisely in

the correct context. It could ask for need-oriented

potential use cases of the shoe (such as sports,

business, clubbing) in order to transform the

technical specifications into a decision aid that is

compatible with the users’ mind setting, language

and mental model.

The operation on the system should be supported

by well-chosen interaction patterns. The toolkit can

take advantage of the retailing context in order to

facilitate and enhance the co-creation process for the

customer. Enabled through e.g. RFID-technology,

physical interaction with a shoe could be tracked.

Thanks to this information the toolkit would know

about the shoe model and the chosen size. A similar

technique could support choice of materials and

colors. Especially in the unknown area of AM,

touching material and surface samples provides a

compelling experience.

One could call this some kind of a push-and-pull-

discourse of customer and terminal-system. The

display of information reacts on the customer’s

testing of the product and samples. Descriptions can

help him discover his own preferences and compare

it to the opportunities provided in the solution space.

This prepares the ground for his purchase decisions.

So far this applies mainly to rational choices,

such as deciding on a material with cushioning

effect. The emotional choice when it comes to

design with shapes or text insets is more difficult to

direct. Sinclair and Campbell (2009) studied whether

participants would prefer sketching or 3d-modelling.

It turned out they preferred to manipulate parameters

of a 3d-object over sketching, even though they

found their design intent better communicated in the

own sketch. Many existing toolkits provide poor

visualizations. One flaw is the inaccuracy of the

representation which partly doesn’t even adapt to the

changes that the customer makes. On the one hand,

AM as method of production already suggests a 3D-

visualization of the object of interest. It may

nonetheless not be a good basis for customization

interactions. Research should focus on this topic.

Continuative approaches of letting users

manipulate 3D-models with touch interaction are

known from the iPad App 123D Sculpt (Autodesk).

The proposed interaction on rubbing on models

surface via a touch screen is convincing from an

interaction designer’s point of view. Unfortunately

there is no data available on the acceptance of that

interaction paradigm. It seems promising to enhance

these interaction patterns with real interactions.

The case of outsole customization offers one

major benefit: for a major part, the customization

can take place in 2d-space. The flat design can later

be extruded into the third dimension. In this way,

images could be drawn on screens to later be

extruded. They could also be integrated into the

modeling-process as a height map. Drawings and

pictures could give texture to the models - photos

could be taken right away at the terminal.

The integration of social networks could deliver

additional benefit. Examples could be:

allowing users to post different designs online in

order to get feedback from peers (value through peer

recognition)

establish an online community where lead users

could answer questions of novice users (reputation

in the community)

allow voting and commenting on best designs

and user-galleries (online dwell times)

collect additional data about preferences,

interest, personal data (usable for collaborative

filtering and reasoning about correlations)

4 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

RESEARCH

Within this paper it was explained that additive

manufacturing (AM) shows potential to be an

extension of the blended shopping concept. Until

now, this is not commercially implemented. The

advantages of the customized blended shopping

concept were described. Merchants and AM

producer will only be able to organize and offer such

consumer added value via web platforms. The

chosen shoe sole use case addresses a scenario

where the customized product is an integral part of a

mass product. This causes besides others logistic,

legal and management problems.

Producing individualized accessories as

independent parts of mass products would overcome

e.g. assembling problems but would give mass

ENHANCINGTHEBLENDEDSHOPPINGCONCEPTWITHADDITIVEMANUFACTURINGTECHNOLOGIES-

AddedValueforCustomers,RetailersandAdditiveManufacturers

499

products an individual look. This can be viewed as

an extended value chain of mass products.

Nevertheless process and data standards need to

be adopted or developed in order to be able to offer

an individualization space limited by the fitting mass

product and production restrictions, to enable

customers to easily configure an accessory and to

hand over the data to production. Underlying logistic

and management processes need to be adopted.

Further considerations need to be drawn on potential

operator models and their implications. Finally a

demonstrator making use of latest internet

technology is needed to visualize the possibilities

and advantages of such a concept.

These research gaps will be subject of a research

project funded by the German Ministry of

Economics and Technology (BMWI).

REFERENCES

Arnold, M. J., and Reynolds, K. E. (2003). Hedonic

shopping motivations. Journal of Retailing, 79(2), 77–

95.

Bauer, H. H. (2010). Typology of Potential Benefits of

Mass Customization Offerings for Customers: An

Exploratory Study of the Customer Perspective. In F.

T. Piller & M. M. Tseng (Eds.), Handbook of research

in mass customization and personalization. New

Jersey: World Scientific.

Chang, C.-C., and Chen, H.-Y. (2009). I want products my

own way, but which way? The effects of different

product categories and cues on customer responses to

Web-based customizations. Cyberpsychology &

Behavior, 12(1), 7–14.

Chang, C.-C., Chen, H.-Y., and Huang, I.-C. (2009). The

interplay between customer participation and difficulty

of design examples in the online designing process

and its effect on customer satisfaction: mediational

analyses. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 12(2), 147–

154.

Davis, S. M. (1987). Future perfect. Reading, Mass:

Addison-Wesley.

Dellaert, B. G. C., and Dabholkar, P. A. (2009). Increasing

the Attractiveness of Mass Customization: The Role of

Complementary On-line Services and Range of

Options. International Journal of Electronic

Commerce, 13(3), 43–70.

Dietrich, A. J., Kirn, S., and Sugumaran, V. (2007). A

Service-Oriented Architecture for Mass

Customization—A Shoe Industry Case Study.

Engineering Management, 54(1), 190–204.

Duray, R., Ward, P. T., Milligan, G. W., and Berry, W. L.

(2000). Approaches to mass customization:

configurations and empirical validation. Journal of

Operations Management, 18(6), 605–625.

Franke, N., and Schreier, M. (2010). Why Customers

Value Mass-customized Products: The Importance of

Process Effort and Enjoyment. Journal of Product

Innovation Management, 27(7), 10201031.

Franke, N., Keinz, P., and Schreier, M. (2008).

Complementing Mass Customization Toolkits with

User Communities: How Peer Input Improves

Customer Self-Design. Journal of Product Innovation

Management, 25(6), 546559.

Fuchs, B., and Ritz, T. (2009). Blended Shopping. In M.

Bick, M. Breunig, & H. Höpfner (Eds.), Mobile und

Ubiquitäre Informationssysteme. Entwicklung,

Implementierung und Anwendung. Proceedings zur 4.

Konferenz MMS 2009 (Vol. 2009, pp. 109–122).

Fuchs, B., and Ritz, T. (2011). Blended Shopping:

Interactivity and Individualization. In ICETE 2011

(Ed.), 8th International Joint Conference on e-

Business and Telecommunications .

Füller, J., Hutter, K., and Faullant, R. (2011). Why co-

creation experience matters? Creative experience and

its impact on the quantity and quality of creative

contributions. R&D Management, 41(3), 259–273.

Gebhardt, A. (2004). Grundlagen des Rapid Prototyping.:

Eine Kurzdarstellung der Rapid Prototyping

Verfahren. RTejournal, 1(1).

Gebhardt, A. (2007). Generative Fertigungsverfahren:

Rapid Prototyping - Rapid Tooling - Rapid

Manufacturing (3rd ed.). München: Hanser.

Gilmore, J. H., and Pine, B. J. (1997). The four faces of

mass customization. Harvard Business Review, 75(1),

91–101.

Grewal, D., Levy, M., and Kumar, V. (2009). Customer

Experience Management in Retailing: An Organizing

Framework. Journal of Retailing, 85(1), 1–14.

Hopkinson, N., Hague, R. J. M., and Dickens, P. M.

(2006). Rapid manufacturing: An industrial revolution

for the digital age. Chichester, England: John Wiley.

Jones, M. A., Reynolds, K. E., and Arnold, M. J. (2006).

Hedonic and utilitarian shopping value: Investigating

differential effects on retail outcomes. Journal of

Business Research, 59(9), 974–981.

Kotler, P., Keller, K. L. and Bliemel, F. (2007).

Marketing-Management: Strategien für

wertschaffendes Handeln (12th ed.). München:

Pearson Studium.

Meffert, H., and Burmann, C. (2008). Marketing:

Grundlagen marktorientierter Unternehmensführung ;

Konzepte - Instrumente - Praxisbeispiele (10th ed.).

Wiesbaden: Gabler.

Merle, A., Chandon, J.-L., Roux, E., and Alizon, F.

(2010). Perceived Value of the Mass-Customized

Product and Mass Customization Experience for

Individual Consumers. Production and Operations

Management, 19(5), 503-514.

Meyer, C., and Schwager, A. (2007). Understanding

Customer Experience. Harvard Business Review,

85(2), 116–126.

Peels, J. (2010). Eleven 3D Printing Predictions For the

Year 2011. Retrieved Aug 13, 2011, from

WEBIST2012-8thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

500

http://techcrunch.com/2010/12/31/3d-printing-

prediction/

Piller, F. T. (2004). Mass Customization: Reflections on

the State of the Concept. International Journal of

Flexible Manufacturing Systems, 16, 313–334.

Piller, F. T., and Stotko, C. (Eds.) 2002. Mass

customization: four approaches to deliver customized

products and services with mass production efficiency.

: Vol. 2.

Pine, B. J. (1993). Mass Customization: The New Frontier

in Business Competition. Boston, MA: Harvard

Business School.

Theis, H.-J. (2006). Erfolgreiche Strategien und

Instrumente im E-Commerce (Vol. 2). Frankfurt am

Main: Dt. Fachverl.

Tian, K. T., Bearden, W. O., and Hunter, G. L. (2001).

Consumers‘ Need for Uniqueness: Scale Development

and Validation. Journal of Consumer Research, 28(1),

50–66.

Tseng, M. M., and Jiao, J. (2001). Mass Customization. In

G. Salvendy (Ed.), Handbook of industrial

engineering. Technology and operations management

(3rd ed., pp. 684–709). New York: Wiley.

van Baal, S., and Hudetz, K. (2008). Das Multi-Channel-

Verhalten der Konsumenten: Ergebnisse einer

empirischen Untersuchung zum Informations- und

Kaufverhalten in Mehrkanalsystemen des Handels.

Köln: IfH.

Verhoef, P. C., Lemon, K. N., Parasuraman, A.,

Roggeveen, A., Tsiros, M., and Schlesinger, L. A.

(2009). Customer Experience Creation: Determinants,

Dynamics and Management Strategies. Journal of

Retailing, 85(1), 31–41.

Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement

motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92(4),

548–573.

ENHANCINGTHEBLENDEDSHOPPINGCONCEPTWITHADDITIVEMANUFACTURINGTECHNOLOGIES-

AddedValueforCustomers,RetailersandAdditiveManufacturers

501