Governance and Privacy in a Provincial Data Repository

A Cross-sectional Analysis of Longitudinal Birth Cohort Parent Participants’

Perspectives on Sharing Adult Vs. Child Research Data

Shawn X. Dodd

1

, Kiran Pohar Manhas

2

, Stacey Page

2

, Nicole Letourneau

3

, Xinjie Cui

4

and Suzanne Tough

5

1

Medical Sciences Graduate Program, University of Calgary, 3820-24

th

Avenue NW, Calgary, Canada

2

Department of Community Health Sciences, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada

3

Faculty of Nursing, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada

4

PolicyWise for Children & Families, Edmonton, Canada

5

Department of Pediatrics, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada

Keywords: Governance, Privacy, Stakeholder Engagement, Child Data, Controlled Access, Vulnerable Populations.

Abstract: Research data abound and are increasingly shared through a variety of platforms, such as biobanks for

precision health and data repositories for reuse of research and administrative data. Data sharing presents

great opportunities as well as significant ethical and legal concerns, such as privacy, consent, governance,

access, and communication. Respectful data governance calls for stakeholder engagement during platform

development. This stakeholder-engagement study used a web-based survey to capture the views of research

participants about governance strategies for secondary data use. Survey response rate was 60.8% (n = 346).

Parents’ primary concern was ensuring appropriate data re-use of data, even over privacy. Appropriate re-use

included project-specific access and limiting access to researchers with more-trusted affiliations like

academia. Other affiliations (e.g. industry, government and not-for-profit) were less palatable. Parents

considered pediatric data more sensitive than adult data and expressed more reluctance towards sharing child

identifiers compared to their own (p-value<0.001). This study stresses the importance of repository

governance strategies to sustain long-term access to valuable data assets via large-scale repository.

1 INTRODUCTION

Originating in the UK and USA, obligatory data

sharing expanding globally (CIHR, 2011; MRC,

2011; NIH, 2003; OECD, 2007). In Canada, national

research funding agencies, including the Social

Sciences and Humanities Research Council

(SSHRC), Canadian Institutes of Health Research

(CIHR), and Natural Sciences and Engineering

Research Council of Canada (NSERC), have issued

policies that highly recommend a range of data

sharing practices (CIHR, NSERC & SSHRC, 2016).

SSHRC funding requires Canadian researchers to

preserve their data and make it available within a

reasonable period of time to other researchers upon

project completion. Data informing peer-reviewed

publications that arose from SSHRC, CIHR or

NSERC funding must be made freely accessible

within 12 months of publication. This publication-

focused policy is expected to extend further to

promote greater accessibility of research outputs and

other research data (CIHR, 2011; CIHR, 2013).

To facilitate these requirements, data-sharing

platforms, such as biobanks and data repositories, are

proliferating. These platforms promote research

transparency and accountability by enabling further

analyses, replications, verifications and refinements

of results (El Emam et al., 2011; MRC, 2011; OECD,

2007). The frequency, diversity, novelty and

complexity of research opportunities increase due to

the expanding wealth of data available. Data sharing

introduces cost savings realized through economies

of scale, benefiting the public, funders, researchers

and trainees (McGuire et al., 2008; MRC, 2011;

OECD, 2007). The contributions of research

participants are maximized, while future research and

respondent burdens are lessened.

The emergence of data-sharing platforms,

highlighted the ethical tensions between individual

208

Dodd, S., Manhas, K., Page, S., Letourneau, N., Cui, X. and Tough, S.

Governance and Privacy in a Provincial Data Repository - A Cross-sectional Analysis of Longitudinal Birth Cohort Parent Participants’ Perspectives on Sharing Adult Vs. Child Research

Data.

DOI: 10.5220/0006430802080215

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Data Science, Technology and Applications (DATA 2017), pages 208-215

ISBN: 978-989-758-255-4

Copyright © 2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

autonomy and the broader, societal good. While

individual consent is the norm for primary research

undertakings, it may or may not be sought when these

data are used for a secondary research purpose.

Currently, Canadian research ethics policy (TCPS2)

permits secondary use of research data to proceed

without consent, if data are de-identified (Article

5.5B, TCPS2) (CIHR, NSERC & SSHRC, 2010). The

implicit trade-off is that the risks of harms to

individuals through the use of their de-identified data

are lesser than the benefits arising to society through

data use and knowledge advancement. Where data are

identifiable, consent considerations direct secondary

use. Waiver of consent is possible, if several, specific

criteria are met (Article 5.5A, TCPS2) (CIHR,

NSERC & SSHRC, 2010). On balance, the

importance of the research question and knowledge

generated must outweigh possible harms to the

welfare of the person to whom the information relates

(CIHR, NSERC & SSHRC, 2010). The TCPS2

advocates engagement with relevant populations to

seek input on ethical issues and appropriate privacy

protection (CIHR, NSERC & SSHRC, 2010).

Recognizing the need for stakeholder input,

researchers have sought adult and adolescent

perspectives on data sharing, primarily in biobanking

contexts. These findings reveal that adults generally

recognize the need to balance research utility (i.e., the

common good) and participant privacy in sharing

genetic data (McGuire et al., 2008; Trinidad et al.,

2012; Trinidad et al., 2010). Privacy risks were

recognized, but permission, notification and

communication issues between biobanks and

participants were their more pressing concerns

(Trinidad et al., 2010; Beskow and Dean, 2008;

Ludman et al., 2010). Research participants generally

express trust in researchers and institutions, but, many

still wish to be asked for permission for the re-use of

their data (Beskow et al., 2008; Ludman et al., 2010).

Parent concerns impacting biobank enrollment for

themselves and their children include lack of

information, risks of stigma, privacy, consent,

researcher credibility questions, and the inability to

be re-contacted for results (Brothers and Clayton,

2012; Neidich et al., 2008; Joseph et al., 2008).

Ethnicity appears to impact biobank participation in

the US, with minorities more reticent than Caucasians

(Halverson and Ross, 2012; Joseph et al., 2008;

Jenkins et al., 2009).

The perspectives of research participants, parents

and children on secondary use of data have

predominantly focused on biological and genetic

data. Treating biobank and epidemiological data

similarly is recognized as inappropriate

(Laurie,

2011; Brakewood and Poldrack, 2013). These data

diverge in their nature, collection, storage, research

potential and implications. Application of standards

developed for the protection of biological data to non-

biological data might not be appropriate. Such

standards may be overly restrictive, wholly

inappropriate, or may disregard unique concerns.

This has relevance for all sectors even beyond health

research as many commercial and research initiatives

deal with personal non-biological information rather

than the limited, unique circumstances of biologics

and genomics. The voices of research participants on

secondary data use are absent. The purpose of this

study is to describe the governance and privacy

preferences of Albertan parent participants from two

longitudinal birth cohorts, when sharing their and

their child’s non-biological research data with a

research data repository.

2 METHODS

A cross-sectional, web-based survey (Dillman et al.,

2009)

sought parent cohort participant views about

governance strategies for secondary use of their and

their child’s data. This survey is part of a broader

mixed-methods study in this population; the

qualitative findings that preceded and informed

survey development are published elsewhere

(Manhas et al., 2015; Manhas et al., 2016).

2.1 Study Population

The target population was all parent participants of

two longitudinal provincial pregnancy cohorts: All

Our Babies (AOB)

(McDonald et al., 2013) and

Alberta Pregnancy Outcomes and Nutrition (APrON)

(Kaplan et al., 2014). These cohorts recruited

pregnant women beginning at 26 weeks gestation and

continuing with nine collection time points over the

subsequent five years. Together, cohort participants

(approximately 6400 people) provided information

on their demographics, lifestyle, mental, psychosocial

and physical health, pregnancy history, health service

utilization, quality of life, and breastfeeding. Detailed

information on these cohorts is described elsewhere

(Kaplan et al., 2014; McDonald et al., 2013).

Email invitations were sent to 569 eligible

participants the AOB cohort and 348 from the APrON

cohort) as we aimed to capture 10% of the cohort

population within the constraints of which

participants consented to contact for survey

invitation). The survey link remained available for

14-days. Reminder emails were sent to participants

Governance and Privacy in a Provincial Data Repository - A Cross-sectional Analysis of Longitudinal Birth Cohort Parent Participants’

Perspectives on Sharing Adult Vs. Child Research Data

209

on days 3 and 11, if the survey remained incomplete.

The AOB cohort participants received a follow-up

call on day 7 to ensure that they received the

invitation and to answer any questions. APrON

cohort preferences did not permit our team to provide

these participants with a follow-up call. Following

completion of the online survey, participants could

submit their e-mail address for entry in a draw for an

iPod Touch, which was kept separate from any data

they provided during survey completion.

Stratified random sampling directed recruitment

toward the following groups to enhance diversity of

responses: (a) father participants; (b) maternal age ≥

30 years at birth of cohort child; (c) maternal age < 30

years at birth of cohort child; and (d) mothers who

self-identify as a minority and/or as new to Canada in

the last five years. Inclusion criteria required that the

parent permitted re-contact for future research on

their original cohort consent form. Exclusion criteria

was limited to previous participation in other aspects

of the

broader mixed-methods study

(Manhas et al.,

2015; Manhas et al., 2016).

2.2 Online Survey Development

Survey content and design based on our previous

qualitative findings, a literature review of stakeholder

engagement in data sharing especially involving

parent perspectives or pediatric data, and pre-testing

using cognitive interviewing with 9 participants (CI)

(Adair et al., 2011).

The final survey consisted of 35 fixed choice

items assessing 5 areas: (a) parents’ motivations and

reservations surrounding participation in research,

data and data repositories; (b) preferences for

protective and organizational approaches for data

repositories; (c) consent preferences; (d) perceptions

of the sensitivity of pediatric data and secondary

research using this data; and (e) communication

preferences with data repositories. Ethics approval

was received from the Conjoint Health Research

Ethics Board, University of Calgary.

2.3 Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize study

variables. Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were

used to describe the association between categorical

variables. As the online survey did not require

participants to answer each question, missing

responses varied by question. The reported

percentages are according to participants who

answered each question, where missing data was not

included in the denominator. When comparing

parents’ willingness to share their or their child’s

identifiers, the four-point willingness scale was

truncated and presented as “willing” and “unwilling”.

The response options “do not care”, “somewhat

willing” and “willing” were collapsed into one

category called “willing”. Analyses were conducted

using STATA for Mac version 14.1 and a significance

level of p<0.05 was used for all tests.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Sample Characteristics

A response rate of 60.8% was achieved (N=346). 105

participants originated from the AOB cohort, 188

originated from the APrON cohort and 50 participants

were members of both cohorts. Amongst these

participants, 96.2% had attended some form of post-

secondary education, 98.0% were female, 69.1%

were over 35 years of age and 86.7% were born in

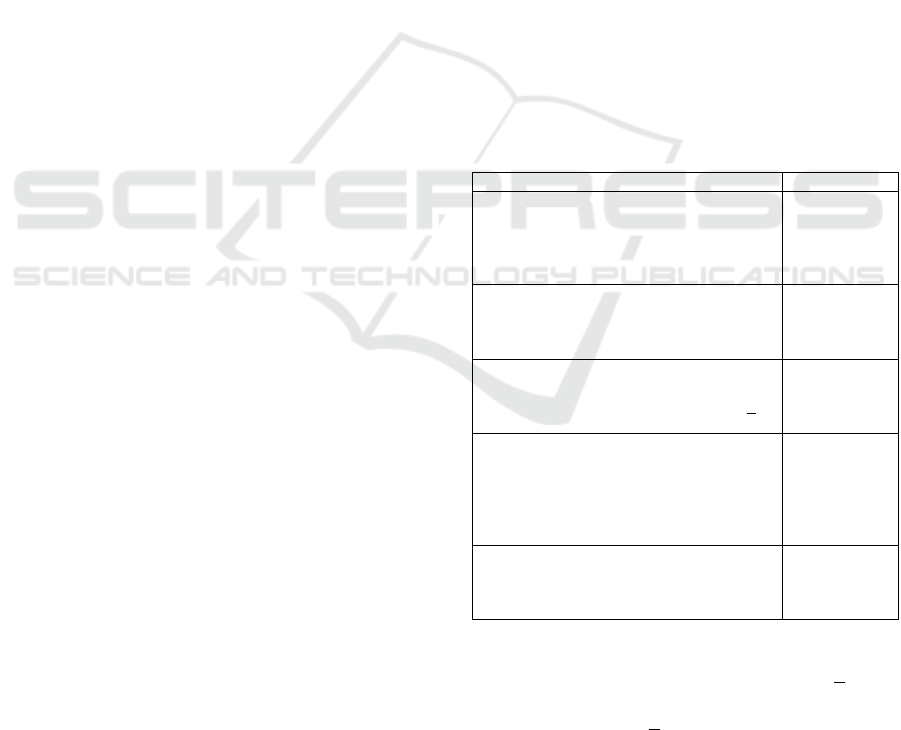

Canada. Table 1 provides a summary of the

respondent characteristics.

Table 1: Characteristics of Participants.

Characteristic N (%)

Longitudinal Birth Cohort

AOB Cohort

APrON Cohort

Both Cohorts

Missing

105 (30.3)

188 (54.3)

50 (14.5)

3 (0.8)

Sex

Male

Female

Missing

5 (1.4)

339 (98.0)

2 (0.5)

Age (years of age)

<35

>35

Missing

138 (39.9)

180 (52.0)

28 (8.1)

Education (highest level, in/complete)

High School

Business, Trade, Technical School

Bachelor’s Degree

Graduate School

Missing

9 (2.6)

51 (14.7)

190 (54.9)

92 (26.6)

4 (1.2)

Country of Origin

Canada

Other

Missing

300 (86.7%)

34 (9.8)

12 (3.4)

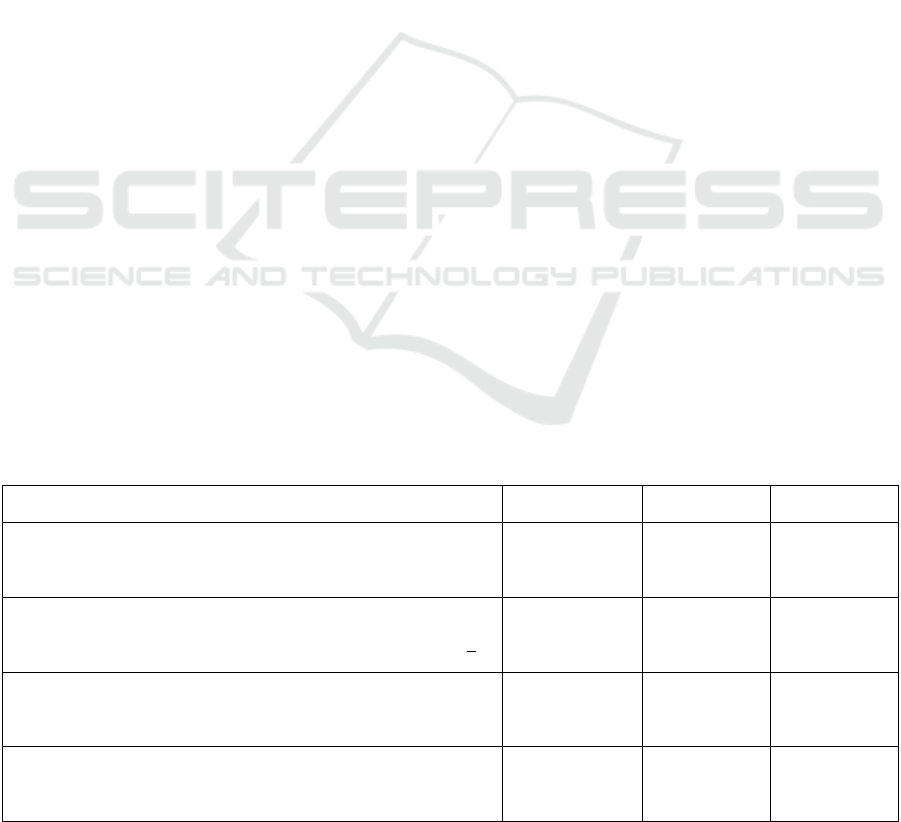

Study recruitment involved stratified random

sampling towards 4 strata, including mothers >30 and

<30 years of age, our sample included a greater

proportion of women >35 years of age than the AOB

and APrON cohorts (Table 2). The remaining

demographic characteristics of our sample were

reflective of both cohorts.

DATA 2017 - 6th International Conference on Data Science, Technology and Applications

210

3.2 Motivations and Reservations

When asked what motivated them to participate in

research generally, 77.4% of parents answered that

they felt research benefits society and wanted to help

advance science. Conversely, 6.1% participants felt

that there were potential benefits for their child, their

family or themselves. Some parents felt that past

experiences with research motivated them to continue

to participate in research (16.5%).

The most important reported benefit of research

data sharing centred on scientific advancement.

Parents indicated that the most important benefit of

data sharing (42.9%) was that new research questions

could be addressed from existing data sets. Another

11.9% of parents believed that data sharing would

benefit science by allowing the primary researchers’

work to be checked. The efficiencies of data sharing

were also viewed from a scientific, rather than

participant, lens. More parents prioritized the cost and

time savings for researchers and funders resulting

from data sharing (40.3%) over the reduced time and

effort burden on research participants (2.9%).

Parents were asked to prioritize their reservations

regarding research data sharing. Ensuring the

appropriate re-use of data was the primary concern

for 61.5% of parents. Protecting participant privacy

was of utmost importance for 36.3% of parents.

Finally, a small minority of parents highlighted

potential logistical concerns with the long-term costs

of supporting a data repository (1.5%).

3.3 Governing Data Access

The survey explored parent participant’s willingness

to make their data available to different types of

secondary users, based on their affiliation. Almost all

parents were quite willing to share their non-

biological research dataset with academic researchers

(e.g. universities: 97.4% willing). However, other

research affiliations were met with greater reluctance:

far fewer parents were willing to share their datasets

with industry (15.9% willing), government (41.6%

willing) and not-for-profit agencies (34.1% willing).

Parents also indicated that their support for data

sharing was dependant on researchers’ motives.

Support was largely received for initiatives that aimed

to uncover new knowledge about children, families

and society (91.6% willing); or to improve public

programs and policies (84.1% willing), and clinical

practices (83.5% willing). When motives were

commercial, parental reservations were noted. Only

38.2% of parents were willing to share datasets when

researcher motives aimed to improve products (i.e.

drug, baby food, etc.), while motives to use the shared

data to increase sales of a product were acceptable for

only 5.2% of parent participants.

Parental input was sought on how to control

secondary researcher’s access once approved. Nearly

three-quarter of participants felt that access should be

limited to the single project described on their

approved data access request (71.5%). Other parents

felt that access should be broader. Sixteen percent of

parents believed that once a researcher gained access,

the dataset could be used for multiple projects;

whereas 12.5% of parents felt that the researchers’

entire research team could access the data to complete

research projects.

The survey solicited parents on how repositories

could best monitor data reuse. There was diversity in

parents’ opinions. Some parents felt that the datasets

should never leave the repository facilities and

analyses should be performed in closed computing

areas (33.3%).

Table 2: Characteristics of Study Sample Compared to AOB and APrON Participant Characteristics.

Characteristic

Study

Sample (%)

AOB

33

(%)

APrON

38

(%)

Sex

Male

Female

Missing

1.4

98.0

0.5

0

100

-

1.4

98.1

0.5

Age (years of age)

<35

>35

Missing

39.9

52.0

8.1

75.8

24.1

-

76.6

23.4

-

Education

High School or less

Post-secondary education

Missing

2.6

96.2

1.2

11.0

89.0

-

9.7

90.3

-

Country of Origin

Canada

Other

Missing

86.7

9.8

3.4

78.1

21.9

-

81.3

18.7

-

Governance and Privacy in a Provincial Data Repository - A Cross-sectional Analysis of Longitudinal Birth Cohort Parent Participants’

Perspectives on Sharing Adult Vs. Child Research Data

211

Other parents felt that repositories should collaborate

with either the researchers’ home institutions (26.1%)

or the researchers’ scientific or professional societies

(7.0%) to monitor researchers. Other parents believed

that regular update reports submitted to the repository

(17.7%) or surprise audits of the secondary

researchers’ facilities and activities (14.8%) would

best safeguard the datasets.

Most parents preferred that the primary researcher

should be involved with the secondary data access

process. Most parents felt that either the primary

researcher should be a member of the decision-

making data access committee (40.8%) or the primary

researcher should at least be informed of all access

requests and given the opportunity to provide their

non-binding opinion on access (42.3%). Few

participants felt that primary researchers should

advise secondary researchers (11.1%) or actively

participate in the secondary research (4.1%).

3.4 Perceptions of Child vs. Adult Data

Parents were asked to consider whether there was a

difference between adult and pediatric data. Parents

generally agreed (69.8%) that there is a difference,

with 59.2% of parents believing that pediatric data

were more sensitive. The survey solicited parent

willingness to share specific identifiers about

themselves and their child with a qualified, secondary

researcher.

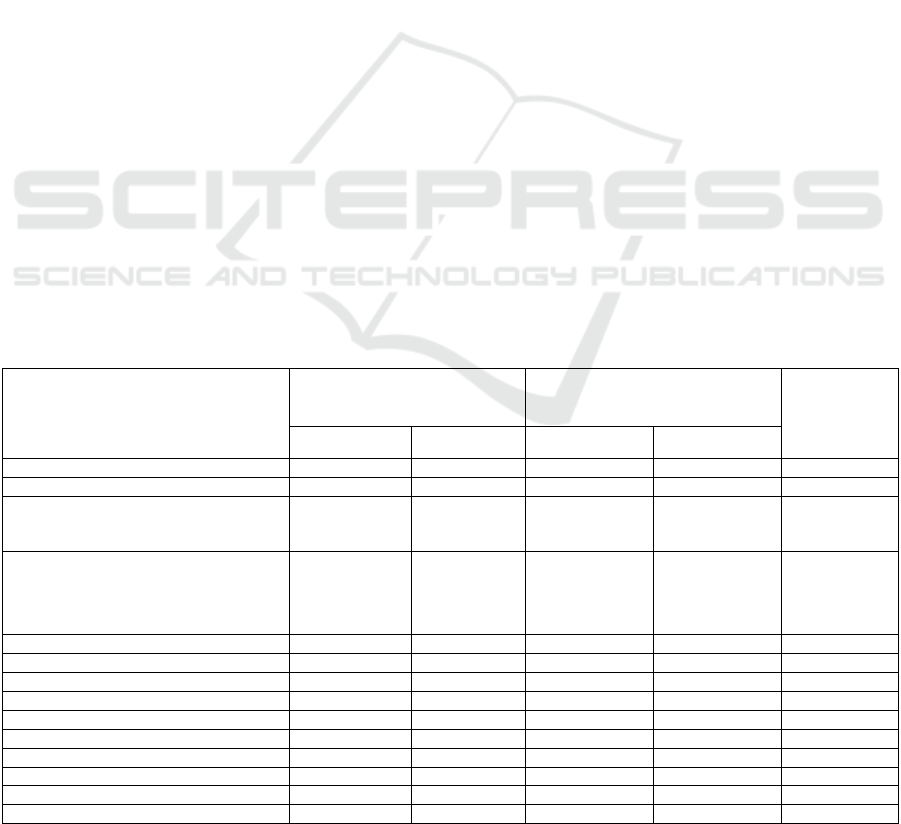

As illustrated in Table 3, of the 13 identifiers

described for adults and the 9 identifiers described for

children, parents were generally willing to share 11

and 7 identifiers, respectively. Parents exhibited little

concern sharing their full name (82.8% willing), their

complete address (72.5% willing) and their complete

date of birth (88.4% willing). Only a small percentage

of parents were unwilling to share their gender (0.3%)

or marital status (1.2%). Parents did, however,

express reluctance to share health care numbers

(40.5% of adults willing to share, 38.0% willing to

share their child’s) and social insurance numbers

(15.1% of adults willing to share, 12.9% willing to

share their child’s).

When comparing willingness of parents to share

their own identifiers compared to their child’s

identifiers, parents’ attitudes changed. Where

applicable, parents expressed more reluctance

towards sharing their child’s identifiers compared to

their own (p-value<0.001; Table 3). The sole

exception was gender (p-value= 0.924), where only

1.2% of parents were unwilling to share their child’s

gender.

The survey also asked parents when identifiers

should be removed from the dataset and by whom.

Parents generally felt that identifiers should be

removed by the primary researcher before submitting

the dataset to a data repository (71.6%). A minority

of parents indicated that removing identifiers was the

role of the data repository and should be done before

the dataset is released to the secondary researcher

(11.7%). Interestingly, 16.7% of parents had no

preference on when or by whom the identifiers were

removed.

Table 3: Willingness of Parent’s to share their, or their child’s identifiers.

Identifier

Willingness to share their

identifier

Willingness to share child’s

identifier

P-value

Willing Unwilling Willing Unwilling

Full Name 279 (82.8) 58 (16.8) 263 (76.0) 83 (24.0) <0.001

Complete Address 251 (72.5) 95 (27.5) 208 (60.1) 138 (39.9) <0.001

Full Postal Code

If no, first 3 Digits of Postal Code

202 (89.4)

87 (92.6)

24 (10.6)

7 (7.4)

189 (75.6)

99 (83.2)

61 (24.4)

20 (16.8)

<0.001

<0.001

Complete Birth Date

If no, month and Year of Birth

If no, year of Birth

306 (88.4)

134 (91.2)

67 (94.4)

40 (11.6)

13 (8.8)

4 (5.6)

280 (81.2)

137 (91.3)

54 (91.7)

65 (18.8)

13 (8.7)

5 (8.3)

<0.001

<0.001

0.001

Contact Information N/A N/A 253 (73.1) 93 (26.9) N/A

E-mail Address 297 (86.3) 47 (13.7) N/A N/A N/A

Phone Number 244 (71.1) 99 (28.9) N/A N/A N/A

Marital Status 340 (98.8) 4 (1.2) N/A N/A N/A

Job 329 (96.2) 13 (3.8) N/A N/A N/A

Gende

r

341 (99.7) 1 (0.3) 338 (98.8) 4 (1.2) 0.924

Ethnicity or Race 335 (99.4) 2 (0.6) 337 (97.7) 8 (2.3) <0.001

Level of Education 339 (99.1) 3 (0.9) N/A N/A N/A

Health Care Number 139 (40.5) 204 (59.5) 131 (38.0) 214 (62.0) <0.001

Social Insurance Number 52 (15.1) 292 (84.9) 44 (12.9) 298 (87.1) <0.001

DATA 2017 - 6th International Conference on Data Science, Technology and Applications

212

4 DISCUSSION & CONCLUSIONS

In general, parents supported the inclusion of their

non-biological research data with a research data

repository. Parents understood the impact that

research has on society and believe that data sharing

supports research initiatives while reducing the time

and cost to researchers and participants. This support

for data sharing came with some reservations.

Ensuring the appropriate re-use of data was the pri-

mary concern for parents. Governance was of greater

concern than privacy. Most empirical explorations of

stakeholder concerns have focused on privacy and

consent questions (Joseph et al., 2008; Kaufman et

al., 2008; Ludman et al., 2010; Malin et al., 2013;

McGuire et al., 2008; Trinidad et al., 2012), while the

more theoretical, ethico-legal analyses have

discussed governance issues (Laurie, 2011). Distinct

from the previous research studies, this study asked

participants to consider and rank between governance

and privacy concerns.

Appropriate re-use of data included sharing it with

researchers that participants trusted such as academic

researchers. Other research affiliations, such as

industry, government and not-for-profit, were met

with greater reticence. This information supports

previous findings that research participants place a

great deal of trust in academic researchers, the

governance and security afforded by their institutions

and their motives towards the greater good, and they

are wary of researchers outside of institutions

(O’Doherty et al., 2011). Even when profit is clearly

not the motive, as for not-for-profit organizations, a

lack trust exists, likely due to perceived institutional

unfamiliarity and possibly lack of security.

Regarding privacy, parents believed that

identifiers should be removed prior to the primary

researcher submitting the data to a repository.

Parents, however, expressed little reservation towards

sharing identifiers, with parents only noticeably less

willing to share their and their child’s health care

numbers and social insurance numbers. This

represents an inconsistency on two levels. Parents

were willing to share information that could combine

to proffer a great deal of information; information that

was available in a single number identifier that

parents were much less willing to share. It is unclear

if the question framing had each parent considering

the identifiers in isolation, or if they felt that their

names and birthdates were less crucial to their privacy

than their health care number and social insurance

number. The former seems unlikely because most

participants seemed to understand that datasets

include more than one variable. The other

inconsistency related to the fact that many parents

wanted the primary researcher to remove identifiers

prior to data sharing; but that parents were willing to

share the majority of identifiers about themselves

(and even their children).

Parental perspectives about governance and

control of data access is quite novel and informative.

Once a primary researcher has submitted a dataset,

parents felt that the primary researcher should either

be a member of a decision-making data access

committee or should be informed of all access

requests and given the opportunity to provide their

opinion on access. Once access was granted, parents

felt that access should be limited to the single project

described by the secondary researcher on the

approved data access request. This conservative

approach to governance and preference for project-

specific access provides complementary information

to the literature supporting broad consent models over

project-specific consent (Caulfield, 2007; Master et

al., 2012; Willison et al., 2008). While project-

specific consent from participants is unpalatable for

many stakeholders due to time and feasibility issues

(Master et al., 2012; McGuire et al., 2008; Trinidad et

al., 2012; Willison et al., 2008), project-level scrutiny

is desired by participants to ensure the security and

respect desired. This coincides with some

commentators in the literature that have recognized

the link between trust in institutions, responsible data

governance, and long-term practical sustainability,

interest and support in large-scale data repositories

including biobanks (Laurie, 2011; O’Doherty et al.,

2011)

There was some diversity amongst parents’

opinions regarding how to ensure that data are being

appropriately re-used. Some parents preferred that

data never leave the repositories and analyses should

be performed in a closed computing area, whereas

others felt that repositories should collaborate with

researcher’s home institutions (if applicable) or

societies to effectively monitor researchers. The key

finding from this paper is that there should be clear

governance at access and monitoring, with parent

participant stakeholders being more flexible on how

monitoring is realized.

When compared to local and provincial data

sources, the participants are generally representative

of the pregnant and parenting population in Calgary

and Alberta

(Leung et al. 2013). Therefore, this study

provides a good sample of Albertan parent

perspectives on data sharing, with certain limitations.

Given that participants were required to have

previously consented to participate in additional

research in their original cohort consent form, our

Governance and Privacy in a Provincial Data Repository - A Cross-sectional Analysis of Longitudinal Birth Cohort Parent Participants’

Perspectives on Sharing Adult Vs. Child Research Data

213

participants may be more supportive of research than

the general population. This may have resulted in an

overestimation of the support the Albertan pregnant

and parenting population may have towards data

sharing.

Another study limitation was a result of the

complexity of the topic. Given the novelty and many

nuances associated with data sharing, it was

recognized during the qualitative component of the

project that participants required additional

information to inform their decisions

(Manhas et al.

2015; Manhas et al. 2016). As such, detailed

background information was provided to participants

for each section of the survey. Though efforts were

made to avoid including information that may

influence participants’ responses, it is possible that

the included information may have altered

participants’ perspectives.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge and thank the

participants for this research project for their time and

insight. We are grateful for the AOB and APrON

research teams. We acknowledge Carol Adair, and

her significant contributions during study design and

proposal development; and Lawrence Richer and his

team’s significant contributions during data

collection in providing ePRO technical support. We

are grateful to PolicyWise for Children & Families,

which provided the external grant funding for the

study and salary support for a principal investigator

(KPM).

REFERENCES

Adair, CE, Holland, AC, Patterson, ML, et al. 2011

‘Cognitive interviewing methods for questionnaire pre-

testing in homeless persons with mental disorders.’

Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York

Academy of Medicine, vol. 89, no. 1, pp. 36-52.

Beskow LM, Dean E, 2008 ‘Informed consent for

biorepositories: Assessing prospective participants'

understanding and opinions.’ Cancer Epidemiology,

Biomarkers & Prevention, vol. 17, pp. 1440-1451.

Brakewood B, Poldrack RA, 2013 ‘The ethics of secondary

data analysis: Considering the application of Belmont

principles to the sharing of neuroimaging data.’

NeuroImage, vol 82, pp. 671-676.

Brothers KB, Clayton EW, 2012 ‘Parental perspectives on

a pediatric human non-subjects biobank.’ AJOB

Primary Research, vol 3, no. 3, pp. 21-29.

Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), 2013 CIHR

open access policy page, http://www.cihr-

irsc.gc.ca/e/46068.html. February 28, 2013.

Caulfield T, 2007 ‘Biobanks and blanket consent: The

proper place of the public good and public perception

rationales.’ Kings Law Journal, vol. 18, pp. 209-226.

CIHR, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council

of Canada (NSERC), Social Sciences and Humanities

Research Council of Canada (SSHRC), 2010. Tri-

council policy statement: Ethical conduct for research

involving humans. Government of Canada, Ottawa,

ON.

Collins D, 2003, ‘Pretesting survey instruments: An

overview of cognitive methods.’ Quality of Life

Research, vol. 12, pp. 229-238.

Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM 2009, Internet, mail

and mixed-mode surveys: The tailored design method.

3rd ed. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ.

El Emam K, Buckeridge D, Tamblyn R, Neisa A, Jonker E,

Verma A 2011, ‘The re-identification risks of canadians

from longitudinal demographics.’ BMC Medical

Informations and Decision Making, vol. 11, pp. 46.

Freedom of information and protection of privacy act.

R.S.A. 2000, c. F-25.

Halverson CME, Ross LF, 2012, ‘Attitudes of african-

american parents about biobank participation and return

of results for themselves and their children.’ Journal of

Medical Ethics, vol. 38, no. 9, pp. 561-566.

Health information Act. R.S.A. 2000, c. H-5.

Jenkins MM, Reed-Gross E, Rasmussen SA, et al., 2009

‘Maternal attitudes toward DNA collection for gene-

environment studies: A qualitative research study.’

American Journal of Medical Genetics, Part A, vol.

149A, pp. 2378-2386.

Joseph JW, Neidich AB, Ober C, Ross LF, 2008, ‘Empirical

data about women's attitudes towards a biobank focused

on pregnancy outcomes.’ American Journal of Medical

Genetics, Part A, vol. 146A, pp. 305-311.

Kaplan BJ, Giesbrecht GF, Leung BM, et al. 2014, ‘The

Alberta Pregnancy Outcomes and Nutrition (APRON)

cohort study: Rationale and Methods’, vol. 10, no. 1,

pp. 44-60.

Kaufman DJ, Murphy-Bollinger J, Scott J, Hudson K, 2009

‘Public opinion about the importance of privacy in

biobank research.’ The American Journal of Human

Genetics, vol. 85, pp. 643-654.

Laurie G 2011, ‘Reflexive governance in biobanking: On

the value of policy led approaches and the need to

recognize the limits of law.’ Human Genetics, vol. 130,

pp. 347-356.

Leung BM, McDonald SW, Kaplan BJ, Giesbrecht GF,

Tough SC, 2013 ‘Comparison of sample characteristics

in two pregnancy cohorts: community-based versus

population-based recruitment methods.’ BMC Med Res

Methodol, vol. 13, pp. 149.

Ludman EJ, Fullerston SM, Spangler L, et al. 2010, ‘Glad

you asked: Participants' opinions of re-consent for

dbGaP data submission.’ Journal of Empirical

Research on Human Research Ethics, vol. 5, no. 3, pp.

9-16.

DATA 2017 - 6th International Conference on Data Science, Technology and Applications

214

Malin BA, El Emam K, O'Keefe CM, 2013, ‘Biomedical

data privacy: Problems, perspectives, and recent

advances.’ Journal of the American Medical

Informatics Association, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 2-6.

Manhas KP, Page S, Dodd SX, Letourneau N, Ambrose A,

Cui X, Tough SC, 2015 ‘Parental perspectives on

privacy and governance for a pediatric repository of

non-biological data.’ Journal of Empirical Research on

Human Research Ethics, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 88-99.

Manhas KP, Page S, Dodd SX, Letourneau N, Ambrose A,

Cui X, Tough SC, 2016 ‘Parental perspectives on

consent for participation in large-scale, non-biological

data repositories.’ Life Sciences, Society & Policy, vol.

12, pp. 1.

Master Z, Nelsn E, Murdoch B, Caulfield T, 2012

‘Biobanks, consent and claims of consensus.’ Nature

Methods, vol. 9, no. 9, pp. 885-888.

McDonald SW, Lyon AW, Benzies KM, McNeil DA, Lye

SJ, Dolan SM, Pennell CE, Bocking AD, Tough SC,

2013, ‘The All Our Babies cohort: Design, Methods,

and Participant Characteristics.’ BMC Pregnancy &

Childbirth, vol. 13, no. suppl 1, pp. S2.

McGuire AL, Hamilton JA, Lunstroth R, McCullough LB,

Goldman A 2008. ‘DNA data sharing: Research

participants' perspectives.’ Genetics in Medicine, vol.

10, no. 1, pp. 46-53.

Medical Research Council 2011, MRC policy and guidance

on sharing of research data from population and

patient studies. MRC, London.

National Institutes of Health 2003, NIH data sharing policy

and implementation guidance page.

http://grants.nih.gov/grants/policy/data_sharing/data_s

haring_guidance.htm. February 28, 2013.

Neidich AB, Joseph JW, Ober C, Ross LF, 2008 ‘Empirical

data about women's attitudes towards a hypothetical

pediatric biobank.’ American Journal of Medical

Genetics Part A, vol. 146A, pp. 297-304.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

(OECD) 2007. OECD principles and guidelines for

access to research data from public funding. OECD,

Paris.

O'Doherty KC, Burgess MM, Edwards K, et al. 2011,

‘From consent to institutions: Designing adaptive

governance for genomic biobanks.’ Social Science &

Medicine, vol. 73, pp. 367-374.

Personal information protection and electronic documents

act. S.C. 2000, c. 5.

SSHRC 2012, Research data archiving policy page.

http://www.sshrc-crsh.gc.ca/about-au_sujet/policies-

politiques/statements-enonces/edata-

donnees_electroniques-eng.aspx. February 28, 2013.

Trinidad SB, Fullerton SM, Bares JM, Jarvik GP, Larson

EB, Burke W, 2010, ‘Genomic research and wide data

sharing: Views of prospective participants.’ Genetics in

Medicine, vol. 12, no. 8, pp. 486-495.

Trinidad SB, Fullerton SM, Bares JM, Jarvik GP, Larson

EB, Burke W, 2012, ‘Informed consent in genome-

scale research: What do prospective participants think?’

AJOB Primary Research, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 3-11.

Willison DJ, Swinton M, Schwartz L, et al. 2008,

‘Alternatives to project-specific consent for access to

personal information for health research: Insights from

a public dialogue.’ BMC Medical Ethics, vol. 9, pp. 18.

Governance and Privacy in a Provincial Data Repository - A Cross-sectional Analysis of Longitudinal Birth Cohort Parent Participants’

Perspectives on Sharing Adult Vs. Child Research Data

215