iOS Apps for People with Intellectual Disability: A Quality

Assessment

Andrés Larco

1

, Freddy Enríquez

1

and Sergio Luján-Mora

2

1

Departamento de Informática y Ciencias de la Computación, Escuela Politécnica Nacional, Quito, Ecuador

2

Departamento de Lenguajes y Sistemas Informáticos, Universidad de Alicante, Alicante, Spain

Keywords: iOS Apps, Intellectual Disability, Quality Assessment, Metrics Measurement.

Abstract: People with intellectual disability should have access to life-long learning opportunities that help them to

acquire essential knowledge and skills. Due to poverty, they may be unable to access basic products and

services such as telephones, television and the Internet. Unequal access to technology has created a digital

divide. However, information and communication technology can help people with intellectual disability in

the interaction with the external environment. The objective of this research was assessing iOS apps quality

for people with intellectual disability using Mobile App Rating Scale. Apps included for evaluation needed

to be educational, in Spanish and free to download. A systematic search was conducted with Preferred

Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses in Apple App Store, finding a total of 958 apps.

After filtering, a total of 42 apps were considered for evaluation using Mobile App Rating Scale. The research

identified seven apps with good quality, with scores over 4. Due to moderately correlation of subjective

customer ratings of Apple App Store with Mobile App Rating Scale score, customer rating is an unreliable

indicator of app quality. The results of this research can help therapists and parents to choose the right app for

people with intellectual disability.

1 INTRODUCTION

Disability is the umbrella term for impairments,

activity limitations and participation restrictions.

Disability is the interaction between individuals with

a health condition (e.g. cerebral palsy, Down

syndrome and depression) and personal and

environmental factors. About 15 % of the world's

population, are estimated to live with some form of

disability (World Health Organization, 2018).

Disability is a development issue, because it may

increase the risk of poverty, and poverty may increase

the risk of disability. A growing body of empirical

evidence from across the world indicates that people

with disabilities and their families are more likely to

experience economic and social disadvantage than

those without disability. Often, “types of disability”

are defined using only one aspect of disability, such as

impairments; sensory, physical, mental, and

intellectual (World Health Organization, 2007, 2011).

The United Nations Organization for Education,

Science, and Culture (UNESCO) estimates that more

than 90 % of children with disabilities in developing

countries do not attend school (UNICEF, 2015). Also,

children with disabilities face discrimination and

stigmatization about their capabilities.

In low and middle-income countries, between

76% and 85 % of people with severe mental disorders

do not receive treatment. Also, the figure in high-

income countries varies between 35 % and 50 %. The

annual global expenditure on mental health is less

than $ 2 per person and less than $ 0.25 per person in

low-income countries. The problem is further

complicated by the poor quality of care received

(World Health Organization, 2013).

Intellectual disability is characterized by

significant limitations in cognitive functioning and

adaptive behavior. Cognitive functioning refers to

general mental capacity, such as learning, reasoning,

problem-solving, and so on. Adaptive behavior is the

collection of conceptual, social, and practical skills

that are learned and performed by people in their

everyday lives (Schalock et al., 2010).

The point 25 of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable

Development of the United Nations pledges to “leave

no one behind”, by committing to provide inclusive

and equitable quality education at all levels. All

people, irrespective of sex, age, race or ethnicity, and

258

Larco, A., Enríquez, F. and Luján-Mora, S.

iOS Apps for People with Intellectual Disability: A Quality Assessment.

DOI: 10.5220/0006778602580264

In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2018), pages 258-264

ISBN: 978-989-758-291-2

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

persons with disabilities, migrants, indigenous peoples,

children and youth, especially those in vulnerable

situations, should have access to life-long learning

opportunities that help them to acquire the knowledge

and skills needed to exploit opportunities and to

participate fully in society (United Nations, 2015).

Nevertheless, not all students have equal

opportunities to access to Information and

communication technology (ICT). Unequal access to

ICT has created a digital divide (Wu, Chen, Yeh,

Wang, and Chang, 2014). ICT can be important for

people with intellectual disabilities. Previous research

showed an evidence of the use of ICT focused on the

main intellectual disabilities. For instance, people

with Down syndrome need more support and

stimulation than unaffected children to function

independently. Therefore, to learn new skills,

activities need to be broken down into smaller steps,

and that more repetition and structure are required for

retention (Felix, Mena, Ostos, and Maestre, 2017).

Also, people with cerebral palsy often have motor

impairment, so it is difficult for them to assist to

school, and by using mobile apps, treatment can go

anywhere with their devices (Griffiths and Addison,

2017). Multitouch tablets, including iPads, have

made computing more accessible for a wide variety

of populations. A previous research indicates that the

simplicity of touch interactions and the portability of

iPads have lowered the barriers for interacting with

computers (Hourcade, Williams, Miller, Liang, and

Huebner, 2013).

There are many app lists in stores, but most of

them are in English and designed for iPad. Aside from

the cost of the iPad itself, parents and therapists need

to consider the cost of each application. Some iPad

applications, including many games, are free (Boyd,

Hart Barnett, and More, 2015). Research has shown

that ratings with stars are subjective based on

popularity, producing little or no meaningful

information (Girardello and Michahelles, 2010), also,

these qualifications may result to be an unreliable

quality metric (Kuehnhausen and Frost, 2013). Besides

that, it is not feasible to evaluate apps with software

quality standards due to its extension, complexity and

general purpose approach (González Reyes, André

Ampuero, and Hernández González, 2015).

However, (Papadakis, Kalogiannakis, and

Zaranis, 2017) present a Rubric for the Evaluation of

Educational Apps for preschool Children (REVEAC)

in four areas: contents, design, functionality, and

technical quality, each having multiple aspects. Later,

(Papadakis, Kalogiannakis, and Zaranis, 2018)

examined educational apps for Greek preschoolers

which have been designed in accordance with

developmentally appropriate standards to contribute

to the social, emotional and cognitive development of

children in formal and informal learning

environments. Another specific and reliable quality

rate tool for mobile health apps is Mobile App Rating

Scale (MARS) (Stoyanov et al., 2015).

A previous study provided a list of 73 Android

apps for therapists and parents who work with people

with Autism, Down syndrome, cerebral palsy and

multiple disabilities (Larco, Yanez, Montenegro, and

Luján-Mora, 2018). Also, an iOS apps evaluation was

made (Larco, Enríquez, and Luján-Mora, in press) for

people with Autism, Down syndrome, and cerebral

palsy. REVEAC had a limitation to be applied to the

present research, it is only focused on preschool

education for children 4 to 6 years of age. Thus, MARS

was chosen over REVEAC to assess app quality due to

its width approach. Also, the research considered iOS

again because apps which do not focus on a specific

disability (in this case intellectual disability in general)

were excluded from previous evaluation.

The objective of this research was assessing iOS

apps quality for children with intellectual disability

using MARS. Apps included for evaluation needed to

be educational, in Spanish and free to download.

A total of 958 apps were initially identified, after

applying Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic

Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA), the

remaining apps (42) were evaluated using MARS.

The research identified seven apps with good quality,

with scores over 4.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2

describes some concepts discussed in the paper.

Section 3 describes the systematic search performed

with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic

Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) and how

MARS can be used to rate app quality. Section 4

describes the results and the relations found between

MARS subscales. Then, section 5 discuss the results.

Finally, section 6 presents conclusions and future

work.

2 BACKGROUND

PRISMA is an evidence-based minimum set of items

for reporting in systematic review and meta-analysis

(Hutton, Catalá-López, and Moher, 2016). In the

health scope, PRISMA has been used in apps

searching to test the reliability of the MARS tool.

MARS is a rate tool for mobile health apps. The

MARS demonstrated excellent internal consistency

(alpha = .90) and interrater reliability intraclass

correlation coefficient (ICC = .79) (Stoyanov et al.,

iOS Apps for People with Intellectual Disability: A Quality Assessment

259

2015). In this research, MARS was used to evaluate

educational iOS apps quality. It was created in the

health environment and contains five subscales:

Engagement refers to fun, interest,

customizable, interactive and target group.

Functionality refers to functioning, ease of

use, navigation, flow logic, and gestural

design.

Aesthetics refers to the graphic design,

visual appeal, color scheme, and stylistic

consistency.

Information refers to high-quality

information from a credible source.

Subjective quality refers to user satisfaction.

MARS and PRISMA have been used in several

researches. For instance, (Sullivan et al., 2016)

identified, described the features, and rated the quality

of smartphone apps that capture personal travel and

dietary behavior and simultaneously estimate the

carbon cost and potential health consequences of these

actions. Apps were searched on Google Play and Apple

App Store and out of 7213 results, 40 apps were

identified and rated. Two researchers using MARS

assessed the quality of included apps.

(Tinschert, Jakob, Barata, Kramer, and Kowatsch,

2017) assessed the potential of available mobile health

apps, for improving asthma self-management. The

Apple App store and Google Play store were

systematically searched for asthma apps. In total, 523

apps were identified, of which 38 apps matched the

selection criteria to be included in the final evaluation

with MARS.

(Grainger, Townsley, White, Langlotz, and Taylor,

2017) assessed features and quality of apps to assist

people to monitor Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) disease

activity, by summarizing the available apps,

particularly the instruments used for measurement of

disease activity, and rating Apps quality with MARS.

Of 71 Android apps retrieved from Google Play Store,

11 apps were included in MARS evaluation. Also,

from 216 iOS apps gathered from New Zealand iTunes

Store, 16 Apps were included for MARS evaluation.

Wikinclusion is a web knowledge base that

contains software according to the competences of life

for PWD. The education-based on competences brings

attention to basic needs and develop different

situations and social contexts in which a person is

involved in his/her daily life (Bayardo, 2005).

Wikinclusion defines seven competences of life: (1)

autonomy, sensorimotor and social skills; (2)

language and communication; (3) mathematics; (4)

the social and natural environment; (5) digital

competence; (6) artistic knowledge; and (7) transition

to the labor market (Wikinclusion, 2017). In this

research, in addition to carry out the quality

evaluation with MARS, apps were classified

according to its respective competence of life.

3 METHODOLOGY

3.1 Systematic Search Criteria and

Selection

A systematic search using PRISMA was performed in

Apple App Store. Apps were searched through a web

page, appAkin, between September and October of

2017, using the terms ‘children OR education OR

puzzles’ in Spanish. Inclusion criteria were: Spanish

language, puzzle games, educational apps, and free to

download.

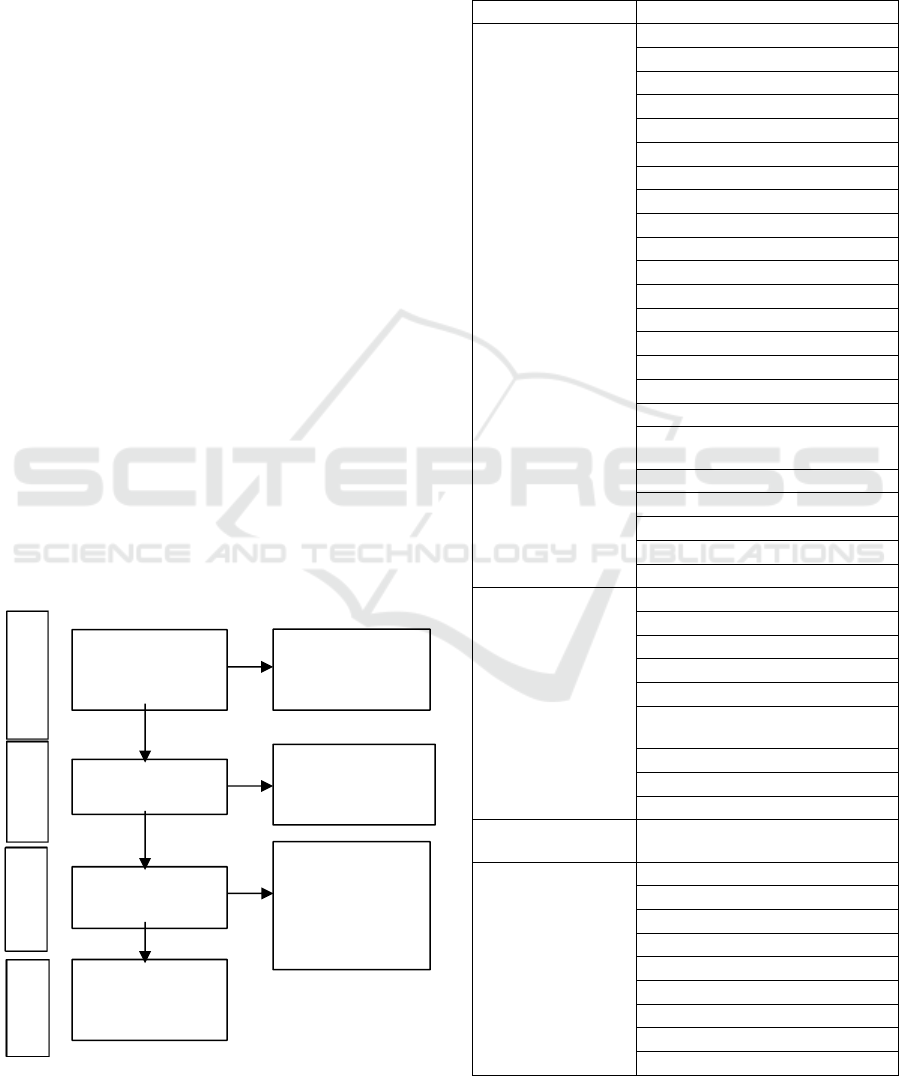

PRISMA consists of a four-phase flowchart

(Liberati et al., 2009). The first phase is identification,

the second one is screening, the third one is eligibility,

and the last one is included.

The exclusion criteria for identification phase

were: paid apps, non-Spanish language apps, and

duplicated apps. On screening phase, the exclusion

criteria were: irrelevant content for children learning.

On eligibility phase, the exclusion criteria were: not

enough information, no longer available, no longer

working and not available in Ecuadorian Apple App

Store. On included phase, the remaining apps were

downloaded and evaluated by testers using MARS.

3.2 Rating Tool

MARS was used to rate mobile apps, and it contains

23 items grouped by five subscales: engagement (5

items), functionality (4 items), aesthetics (3 items),

information (7 items) and subjective quality (4 items).

The average of the first four subscales determines the

app quality score. MARS items use a Likert scale (1-

Inadequate, 2-Poor, 3-Acceptable, 4-Good, 5-

Excellent) (Masterson Creber et al., 2016).

A team of 14 testers performed the evaluation;

each tester was assigned a minimum of three

applications to evaluate. A template was created for

data extraction following MARS scale. Inside the

template, the first section contains app information;

the second one contains app quality ratings, the third

one contains subjective app quality, and the last one

presents a summary of MARS subscales. Also, testers

classified every app according to its respective

competence of life. Training sessions for testers were

performed about the process of how to evaluate apps

using the templates. Included apps were evaluated on

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

260

the following devices: iPhone 5s, iPhone 6, iPad 1,

iPad Mini and iPad Air.

3.3 Data Analysis

ICC determined the interrater reliability of MARS

subscales. The ICC form used in this research was a

two-way mixed-effects model because the result only

represents the reliability of the specific raters

involved in the reliability experiment (Koo and Li,

2016). The confidence interval (CI) is a type of

interval estimate that was computed from the

observed data. The confidence level is the frequency

of possible confidence intervals that contain the real

value of their corresponding parameter. The most

common confidence level is 95 % (Gupta, 2012).

Pearson correlation coefficient is a measure between

sets of data and how well they are related (Mukaka,

2012). Finally, data was analyzed using IBM SPSS

Statistics 23.

4 RESULTS

A total of 958 apps were searched through appAkin

choosing the filter "Free-Only". Irrelevant app cate-

gories such as Productivity, Apps, Lucky Charms,

Cooking Recipes were excluded. Apps were searched

with the terms intellectual disability, kids, education,

education kids and puzzle. Apps were filtered through

categories such as educational, education, family

games and music for kids. Finally, 42 apps were

Figure 1: Systematic search of apps.

included in the final evaluation. Fig. 1 shows the

results of the search.

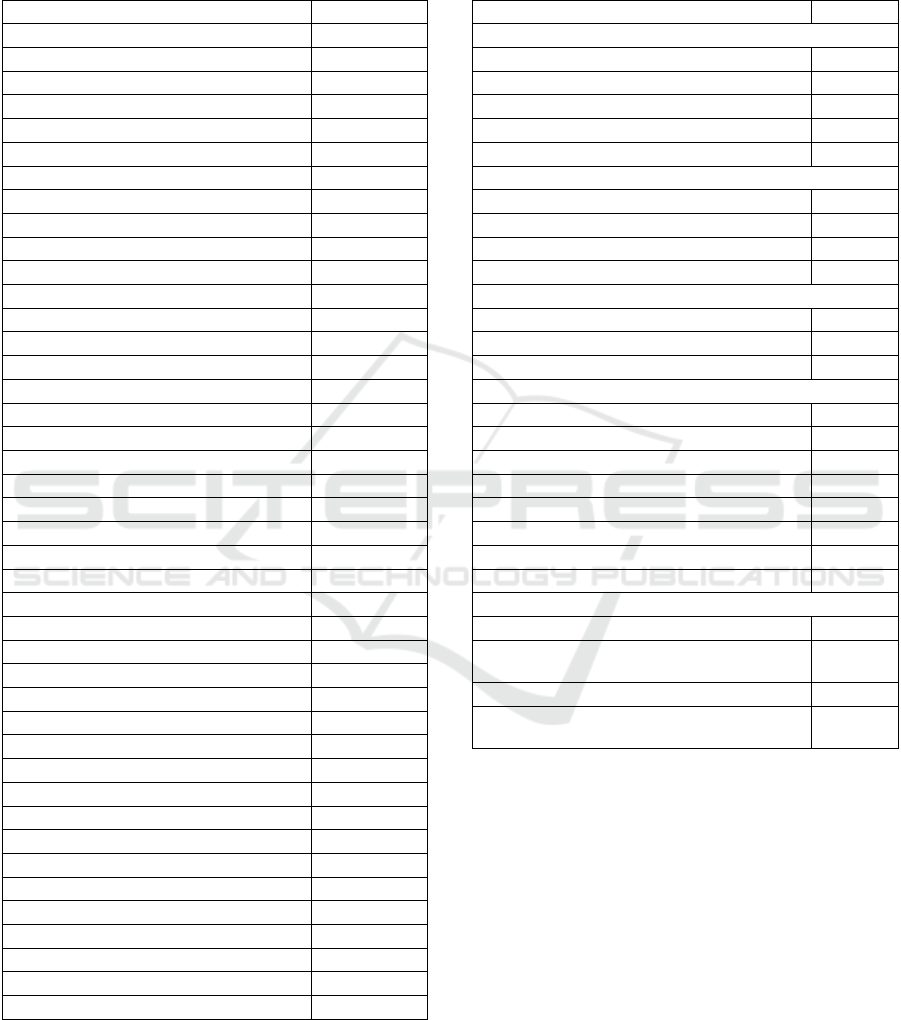

Table 1 contains apps grouped by its respective

competence of life.

Table 1: Apps by competence of life.

Competence of life App name

Autonomy,

sensorimotor and

social skills

Animal Train for Toddlers

Animated Puzzle 1

Animated Puzzle 2

Animated Puzzle 3

Build a Toy 1

Build-it-up

Chromville

CI Niños

Crazy Kitty Tap

Dilo en señas

Dot.2.Dot

Families 1

Find-It

Fit Brains for Kids

Match it up

Matrix Game 1

Opposites 1

Patrones para Niños versión

gratis

Puzzle Me 1

Puzzle Me 2

Sorting Game

Things to Learn

What's Diff 2

Language and

communication

Abecedario 1.0 G

Busca la Letras Lite

Dime paint lite

Families 2

Leo Con Grin

My First Book of Spanish

Alphabets

NaturalReader Text to Speech

NeoRom

Piruletras

The social and

natural environment

Adivina el animal versión Gratis

Mathematics

Kely Sumar y Restar

Matemáticas con Grin

Matemáticas con Grin II – 678

Pop Math Lite

Series 1

Series 2

Series 3

Shapes Jigsaw

Tikimates: multiplicar y dividir

Identification

Apps identified in Apple

App Store through appAkin

(n = 958)

Screening

Eligibility

Included

Apps excluded (n=870):

• Duplicated

• Non-Spanish language

Apps screened

(n = 88)

Apps excluded (n = 31):

Irrelevant content for children

learning

Apps assessed for eligibility

(n=57)

Apps excluded (n = 15)

• Not enough information

• No longer available

• No longer working

• Not available in Ecuador

Apps downloaded for

MARS evaluation

(n = 42)

iOS Apps for People with Intellectual Disability: A Quality Assessment

261

Table 2 contains MARS total score for each app, it

was calculated based on engagement, functionality,

aesthetics, and information.

Table 2: MARS scores for each app.

App name MARS

Kely Sumar y Restar 4.53

Tikimates: multiplicar y divider 4.26

Busca la Letras Lite 4.21

Chromville 4.13

Series 1 4.13

Patrones para Niños - Versión Gratis 4.11

Dilo en señas 4.09

Crazy Kitty Tap 3.95

Families 2 3.87

Fit Brains for Kids 3.82

Find-It 3.66

Build-it-up 3.64

Build a Toy 1 3.63

Series 2 3.62

Animal Train for Toddlers 3.61

Opposites 1 3.61

Dot.2.Dot 3.59

Match it up 3.58

Series 3 3.51

Adivina el animal version Gratis 3.50

Dime paint lite 3.49

Things to Learn 3.46

NaturalReader Text to Speech 3.46

NeoRom 3.43

What's Diff 2 3.36

Shapes Jigsaw 3.36

Animated Puzzle 1 3.35

Animated Puzzle 3 3.35

Animated Puzzle 2 3.34

Puzzle Me 2 3.34

Puzzle Me 1 3.30

Families 1 3.29

Abecedario 1.0 G 3.29

Matrix Game 1 3.27

Pop Math Lite 3.15

Leo Con Grin 3.06

Sorting Game 3.00

Piruletras 2.97

Matemáticas con Grin II - 678 2.97

Matemáticas con Grin 2.97

CI Niños 2.42

My First Book of Spanish Alphabets 1.68

Table 3 contains the mean of the 23 items of MARS

subscales for the 42 evaluated apps. Each subscale

has its ICC, used to demonstrate the acceptable level

of reliability among evaluators.

Item 19 “Evidence base” was excluded from all

calculations, as it currently contains no measurable

data (Stoyanov et al., 2015).

Table 3: Statistics of the 23 items of MARS.

Subscale/Item Mean

Engagement ICC = 0.77 (95 % CI 0.63 - 0.86)

1. Entertainment

3.69

2. Interest

3.55

3.Customization

2.55

4. Interactivity

2.52

5. Target group

3.88

Functionality ICC = 0.78 (95 % CI 0.65 - 0.87)

6. Performance

4.07

7. Ease of use

3.81

8. Navigation

4.00

9. Gestural design

3.83

Aesthetics ICC = 0.84 (95 % CI 0.84 - 0.93)

10. Layout

3.88

11. Graphics

3.74

12. Visual appeal

3.76

Information ICC= 0.63 (95 % CI 0.43 - 0.77)

13. Accuracy of app description

3.95

14. Goals

2.93

Subscale/Item Mean

15. Quality of information

3.12

16. Quantity of information

3.07

17. Visual information

3.36

18. Credibility

3.31

19. Evidence base

-

Subjective quality ICC= 0.94 (95 % CI 0.91-0.97)

20. Would you recommend this app? 3.17

21. How many times do you think you

would use this app?

3.57

22. Would you pay for this app? 3.29

23. What is your overall star rating of the

app?

3.29

5 DISCUSSION

The apps searched needed to be in Spanish due to the

target group. However, it can be noted that the name

of several applications is in English, thus, language

description of each app was carefully reviewed, and

some apps were found with multilanguage content.

Despite the search criteria were in Spanish, the

accuracy of the results was low due to the inadequate

quality description of apps. Also, subcategories

presented by appAkin contained several apps

duplicated. Thus, 870 apps were dismissed of 958.

According to the MARS scale, seven apps of forty-

two obtained a good quality (scores over 4), which

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

262

means thirty-five apps were poorly designed, only

good quality apps would be strongly recommended for

their use by therapists, parents, and people with

intellectual disability.

For autonomy, sensorimotor and social skills

competence the best-rated app was Chromville

(4.13), for language and communication competence,

the best-rated app was Busca Las Letras Lite (4.21).

Finally, for mathematics competence, the best-rated

app was Kelly Sumar y Restar (4.53).

Apps with MARS score below 3 presented similar

problems. Apps did not contain a settings section,

functionality of the app was slow and broken in some

parts (like buttons), the movement between screens

(such as sliding) was also slow and lacks attraction.

Same color for most of the content. Free content was

limited, but the paid content was offered. The

exactitude of item/options selection was low. Middle

or low quality of the images or graphics within the

app.

The best-rated subscale was functionality with a

mean value of 3.93; the reason is on performance

(4.07), navigation (4.00), gestural design (3.83) and

ease of use (3.81) of the evaluated apps. On the other

hand, the reason engagement had the lowest mean

score (3.24) was a lack of customization (2.55) and

interactivity (2.52) of the evaluated apps. The MARS

total mean score of subscales had a good reliability

(ICC = 0.79), which means there is a high consistency

in measurements of MARS items made by testers.

Inside Apple App Store, every time developers

release a new version of an app, the star rating

provided by customers is deleted. As a result,

customer ratings of Apple App Store were available

on 67 % (28/42) of the evaluated apps. Customer

ratings available on apps were moderately correlated

with the MARS total score (Pearson correlation

coefficient = 0.40).

6 CONCLUSIONS

Evaluated apps presented minor performance

problems, and there was a lack of specific, measurable

and achievable goals in the description of apps. The

absence of customization and interactivity in free apps

is due to the target group of Apple products is focused

on people with a premium income level. Free apps

have an absence of customization and interactivity

this occurs due iOS developers focus their efforts to

develop paid apps for people with a premium income

level. These characteristics are important because they

could improve the engagement of people with

intellectual disability when using apps.

Due to moderately correlation of subjective

customer ratings of Apple App Store with MARS

score, customer rating is an unreliable indicator of app

quality. It should not be considered because it is not

focused on people with intellectual disability.

However, the list of evaluated apps generated by this

research can help therapists and parents to choose

from the list the right app for people with intellectual

disability avoiding the confused and independent

search for apps due to the non-existence of store

categorizations by disability type and app quality.

Also, the research identified which apps help to

develop specific competences of life (such as

autonomy, sensorimotor and social skills; language

and communication; and mathematics) with the

purpose of helping people with intellectual disability.

The main competence for the evaluated apps was

autonomy, sensorimotor and social skills (55 %) since

it is essential for people with intellectual disability in

their daily activities. Also, no apps were found for the

competences artistic knowledge, digital competence

and transition to the labor market.

It is incorrect to tag people with disabilities,

therapists and parents of people with intellectual

disability could use apps for kids because apps need to

be focused on people with and without intellectual

disability.

REFERENCES

Bayardo, M. G. M. (2005). Educación de calidad y

competencias para la vida. Revista Educar, 35, 25–32.

Boyd, T. K., Hart Barnett, J. E., and More, C. M. (2015).

Evaluating iPad technology for enhancing communica-

tion skills of children with Autism Spectrum Disorders.

Intervention in School and Clinic, 51(1), 19–27.

Felix, V. G., Mena, L. J., Ostos, R., and Maestre, G. E.

(2017). A pilot study of the use of emerging computer

technologies to improve the effectiveness of reading

and writing therapies in children with Down syndrome:

Emerging computer tool for learning in children with

DS. British Journal of Educational Technology, 48(2),

611–624.

Girardello, A., and Michahelles, F. (2010). AppAware:

Which mobile applications are hot? In Proceedings of

the 12th international conference on Human computer

interaction with mobile devices and services (pp. 431–

434). ACM.

González Reyes, A., André Ampuero, M., and Hernández

González, A. (2015). Análisis comparativo de modelos

y estándares para evaluar la calidad del producto de

software. Revista Cubana de Ingeniería, VI(3).

Grainger, R., Townsley, H., White, B., Langlotz, T., and

Taylor, W. J. (2017). Apps for People with Rheumatoid

Arthritis to Monitor Their Disease Activity: A Review

iOS Apps for People with Intellectual Disability: A Quality Assessment

263

of Apps for Best Practice and Quality. JMIR MHealth

and UHealth, 5(2), e7.

Griffiths, T., and Addison, A. (2017). Access to

communication technology for children with cerebral

palsy. Paediatrics and Child Health. Retrieved from

http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S17517222

17301452

Gupta, S. K. (2012). The relevance of confidence interval

and P-value in inferential statistics. Indian Journal of

Pharmacology, 44(1), 143–144.

Hourcade, J. P., Williams, S., Miller, E., Liang, L., and

Huebner, K. (2013). Evaluation of Tablet Apps to

Encourage Social Interaction in Children with Autism

Spectrum Disorders. In CHI 2013: Changing

Perspectives (pp. 3197–3206). Paris, France.

Hutton, B., Catalá-López, F., and Moher, D. (2016). La

extensión de la declaración PRISMA para revisiones

sistemáticas que incorporan metaanálisis en red:

PRISMA-NMA. Medicina Clínica, 147(6), 262–266.

Koo, T. K., and Li, M. Y. (2016). A Guideline of Selecting

and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for

Reliability Research. Journal of Chiropractic

Medicine, 15(2), 155–163.

Kuehnhausen, M., and Frost, V. S. (2013). Trusting

smartphone apps? To install or not to install, that is the

question. In 2013 IEEE International Multi-

Disciplinary Conference on Cognitive Methods in

Situation Awareness and Decision Support (pp. 30–37).

Larco, A., Enríquez, F., and Luján-Mora, S. (in press).

Review and evaluation of special education iOS Apps

using MARS. EDUNINE 2018.

Larco, A., Yanez, C., Montenegro, C., and Luján-Mora, S.

(2018). Moving Beyond Limitations: Evaluating the

Quality of Android Apps in Spanish for People with

Disability. In Proceedings of the International

Conference on Information Technology & Systems

(ICITS 2018) (Vol. 721, pp. 640–649). Cham: Springer

International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-

3-319-73450-7_61

Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C.,

Gotzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P. A., … Moher, D.

(2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting

systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that

evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and

elaboration. BMJ, 339(jul21 1), b2700–b2700.

Masterson Creber, R. M., Maurer, M. S., Reading, M.,

Hiraldo, G., Hickey, K. T., and Iribarren, S. (2016).

Review and Analysis of Existing Mobile Phone Apps

to Support Heart Failure Symptom Monitoring and

Self-Care Management Using the Mobile Application

Rating Scale (MARS). JMIR MHealth and UHealth,

4(2), e74.

Mukaka, M. M. (2012). A guide to appropriate use of

correlation coefficient in medical research. Malawi

Medical Journal, 24

(3), 69–71.

Papadakis, S., Kalogiannakis, M., and Zaranis, N. (2017).

Designing and creating an educational app rubric for

preschool teachers. Education and Information

Technologies, 22(6), 3147–3165. https://doi.org/10.

1007/s10639-017-9579-0

Papadakis, S., Kalogiannakis, M., and Zaranis, N. (2018).

Educational apps from the Android Google Play for

Greek preschoolers: A systematic review. Computers &

Education, 116, 139–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.compedu.2017.09.007

Schalock, R. L., Borthwick-Duffy, S. A., Bradley, V. J.,

Buntinx, W. H. E., Coulter, D. L., Craig, E. M., …

Yeager, M. H. (2010). Intellectual Disability:

Definition, Classification, and Systems of Supports.

Eleventh Edition. American Association on Intellectual

and Developmental Disabilities.

Stoyanov, S. R., Hides, L., Kavanagh, D. J., Zelenko, O.,

Tjondronegoro, D., and Mani, M. (2015). Mobile App

Rating Scale: A New Tool for Assessing the Quality of

Health Mobile Apps. JMIR MHealth and UHealth,

3(1), e27.

Sullivan, R. K., Marsh, S., Halvarsson, J., Holdsworth, M.,

Waterlander, W., Poelman, M. P., … Maddison, R.

(2016). Smartphone Apps for Measuring Human Health

and Climate Change Co-Benefits: A Comparison and

Quality Rating of Available Apps. JMIR MHealth and

UHealth, 4(4), e135.

Tinschert, P., Jakob, R., Barata, F., Kramer, J.-N., and

Kowatsch, T. (2017). The Potential of Mobile Apps for

Improving Asthma Self-Management: A Review of

Publicly Available and Well-Adopted Asthma Apps.

JMIR MHealth and UHealth, 5(8), e113.

UNICEF. (2015). The Investment Case for Education and

Equity Executive Summary.

United Nations. (2015, October 21). Transforming our

world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Wikinclusion. (2017). Wikinclusion. Retrieved November

4, 2017, from http://wikinclusion.org/index.php/

Página_principal

World Health Organization (Ed.). (2007). International

classification of functioning, disability and health:

Children & youth version. Geneva.

World Health Organization. (2011). World report on

disability. Geneva: World Health Organization.

World Health Organization. (2013). Mental Health Action

Plan 2013-2020.

World Health Organization. (2018). Disability and health.

Retrieved January 27, 2018, from http://www.who.int/

mediacentre/factsheets/fs352/en/

Wu, T.-F., Chen, M.-C., Yeh, Y.-M., Wang, H.-P., and

Chang, S. C.-H. (2014). Is digital divide an issue for

students with learning disabilities? Computers in

Human Behavior, 39, 112–117.

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

264