Learning virtual project work

Pentti Marttiin

1,3

, Göte Nyman

2

, Jari Takatalo

2

, Jari A. Lehto

3

1

Department of Information Systems, Helsinki School of Economics, P.O. Box 11, Finland

2

Department of Psychology, University of Helsinki, P.O. Box 9, Finland

3

Nokia Technology Platforms, P.O. Box 45, 00045 Nokia Group, Finland

Abstract. There are a variety of challenges in organizing productive virtual

collaboration projects. Problems of commitment and co-ordination are all

common. Organized use of collaboration technologies with appropriate

organization and management of activities can help avoid these obstacles. We

have developed and tested a model that is intended to support learning of

project management and virtual teamwork. It can be applied for introducing

collaboration models and practices to global firms, or as we have done, to

collaboration between university seminars. The model includes a multi-layered

organization structure according to which virtual or semi-virtual teams are built.

Facilitation of the exercise is supported with students operating in two layers:

coordination and reflection layers. The model has evolved and we report

experiences from tests with two seminars during 2003. The first seminar was

arranged between courses at three universities, and two universities was

participating the second one. We describe the basic constructs of the model, our

experiences and preliminary results of studies.

1 Introduction

Virtual and especially semi-virtual communication, collaboration, and learning have

become an essential part of organizational life. Unpredictable and dramatic factors

such as September 11th and the recent sars epidemic have boosted the need for distant

collaboration. Global organizations, subcontractor networks, distributed teams, and

many other areas of production and services meet the challenge.

While it is customary to discuss virtualness mainly as an entity of its own [6, 8, 15,

16], the de facto challenge of present organizations is how to best manage the mix of

their virtual and other activities. Virtual collaboration can become expensive in terms

of human resources and time needed for communication and coordination. The

adoption of new tools may introduce unpredicted organizational friction due to

insufficient understanding of roles and networked performance. A strong

organizational culture can even prevent novel interaction through the network [18],

and the lack of shared contextual experiences between members can cause inefficient

communication and motivation [13].

We can distinguish between two learning strategies in utilizing information and

communication technology (ICT). In the open, self-organizing, approach individuals

and organizational units are supported in their activities by offering access to

databases, links, services and applications through numerous channels [12]. In doing

Marttiin P., Nyman G., Takatalo J. and A. Lehto J. (2004).

Learning virtual project work.

In Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Computer Supported Activity Coordination, pages 91-102

DOI: 10.5220/0002681500910102

Copyright

c

SciTePress

so organizations and individuals are trusted to be capable of using new tools and

materials for their benefit. The focus is in finding and developing optimal tools and

environments. The open strategy is not uncommon to most business organizations,

perhaps because of the richness of technologies and business processes that exist.

In the closed or integrated approach, certain application environments or working

models are provided to support projects (e.g. http://www.knowledgeforum.com

).

Typically, a software framework, application, or model of individual or organizational

work is applied to provide the structure and function for the work. The selected

collaboration model and groupware are often used to support work processes.

In practice, there is a need to apply a mixed strategy. Reasons for this include fast

changing technology, a risk of incompatibility in adopting new tools, and an ongoing

change that concerns both information technology and organizational structure and

processes. Whatever the particular situation is, organizations must rely on virtual or

semi-virtual processes that are built according to an explicit or implicit model of

collaboration. Such models are not abundant and, hence, people in organizations must

continuously learn new ways of virtual collaboration and project work.

In this paper we present a model for learning project management and virtual

teamwork. We believe that a mixed strategy with a planned co-ordination and

reflection is beneficial especially in cases where the members of the virtual or

distributed team do not share a common organizational history or apply a predefined

process model. This is typical e.g. for new distributed teams, collaboration networks

consisting of variable organizational cultures, and for new members of organizations.

The model is called Virtual Project Model (VPM) and it aims to constitute a

structure for a “learning by doing” exercise. VPM contains layers of co-ordination

and reflection. Tasks are partly emergent and self-organized as in open model. The

exercise reported in this paper was arranged twice as a part of higher education

courses: the first exercise between three Finnish Universities (Spring 2003) and the

second one (Fall 2003) between two Universities involved also in the earlier exercise.

The coordination layer details differed between exercises. Based on our experiences

we believe participants can become committed if they are guaranteed a well-defined

structure of collaboration and a certain amount of power and responsibility.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the basic concepts of the

VPM. We use coordination theories to discuss how co-ordination is arranged. Section

3 goes through two seminars in which the VPM has been applied and tested. We also

discuss our experiences and show preliminary results of studies done during the

exercises. Section 4 presents concluding remarks and future work.

2 Virtual Project Model

Originally, the development of Virtual Project Model (VPM) had the goal to support

reflection of distributed collaboration experiences. When consulting distributed

projects at Nokia [10], we built an approach to increase management’s knowledge of

various individual, team, and community related aspects. We concluded that teaching

these aspects and practices require an organized interplay between individuals sharing

a common task. In order to develop and test VPM we arranged a joint exercise

between University seminars. It is based on the following principles:

92

1. Learning by doing,

2. Individual commitment,

3. A model of collaboration, and

4. Technology independence.

Firstly, the purpose of VPM exercise has been to give students possibility to learn

and enhance their skills in the areas of project management and teamwork, especially

in a distributed environment. It is necessary to give students means to conceptualize

and experiment [11, 14]. Before starting the exercise we provided relevant practices

and tips [4, 6], process models [7] and frameworks [8, 10].

Secondly, project groups and also university seminars that do not share

organizational or other contextual motivation for collaboration may suffer from the

lack of commitment and isolation of member activities. In order to achieve a better

motivational basis for collaboration the exercise takes place as interplay between

teams, participants have a responsibility to act and interact, and a sufficient feedback

is guaranteed. A time window is reserved for teams to build their team identities, e.g.

imaginary company, logos, and virtual places (see [7]).

Thirdly, VPM is based on a model of collaboration: it embodies structures enabling

communication, co-ordination and reflective feedback. Goals are given on a coarse

level but details are left emergent. Communication and co-ordination processes are

discussed in Sections 2.1 and 2.2, and reflection processes in Section 2.3.

Finally, the exercise is carried out with the help of various ICT tools including

phone, e-mail, videoconferences, discussion areas, and shared repositories.

Technology is not the main focus on the exercise. Instead, people choose among the

tools they have. Our goal is to make VPM work for virtual teams. However, teams in

our exercises are semi-virtual, that is, only some participant worked virtually.

2.1 Teams and responsibilities in VPM

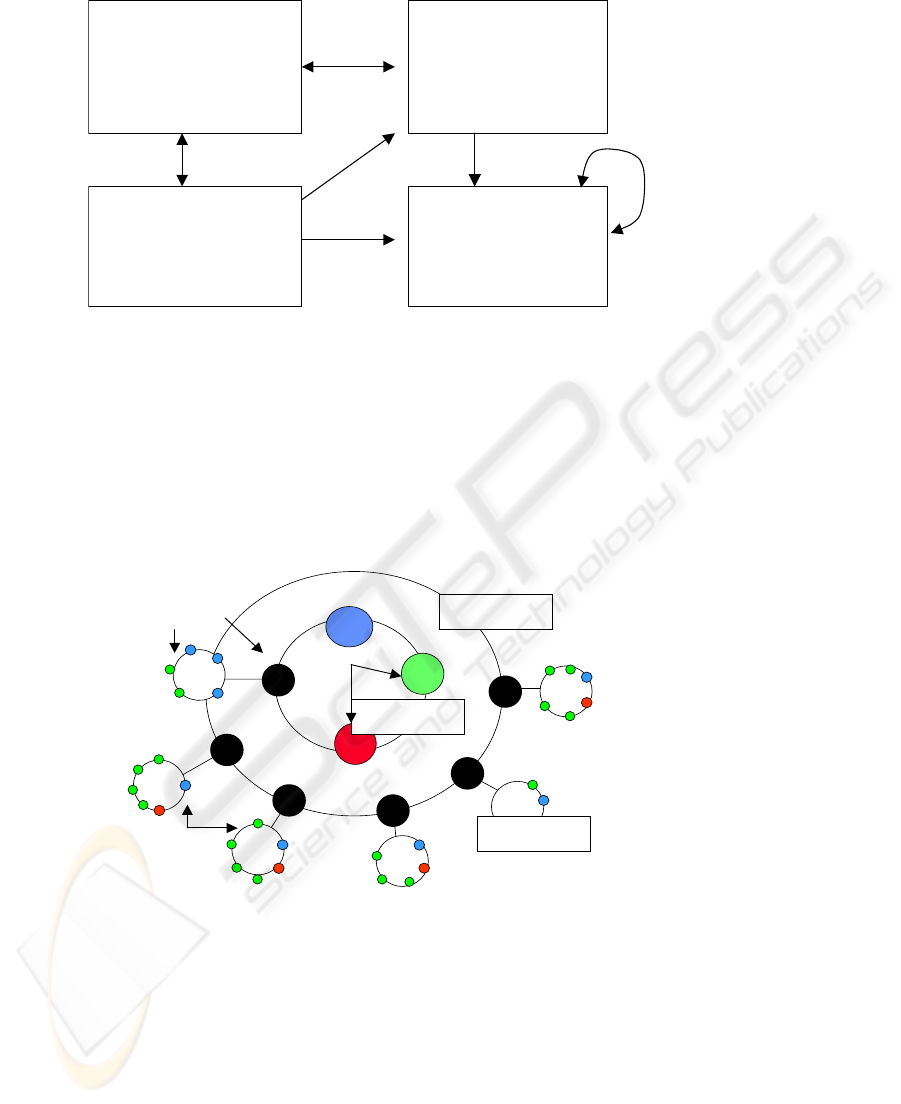

We applied a multi-layered structure in which various parties are dependent on each

other. The parties are: Facilitators (Lecturers and Assistants), Co-ordination team

(Students), Sub-contracting teams (Students), and Research team (Students). Figure 1

shows the responsibilities and dependencies of each team.

Cross et al. [2] presented two important viewpoints in their discussion of myths in

networks. Firstly, when a network grows large no single actor knows what takes place

in the network. Secondly, when one key actor is becoming a bottleneck her tasks need

to be delegated. Several emergent situations that require quick reaction may occur.

Because of that we have arranged communication between facilitators and virtual

teams through the co-ordination team that is more aware of the whole process and

situation.

93

V

IRTUAL TEAMS

•

Sub-goal and

collaborative tasks

•

Role of project manager

•

Self-organized

RESE

A

RCH TEAM

•

Study the exercise and

teams

•

Utilization of frameworks

•

Reflective, results as

feedback

CO-ORDINATION TEAM

•

Goal decomposition

•

Co-ordination over teams

•

Tasks delegated from

facilitators

•

Self-organized

FACILITATORS

•

Learning initiative and goals

•

Tasks and instructions

(a customer)

•

Network environment

•

Collaboration model

communicate

interfaces

analyse,

reflect

coordinate specify

research

specify

coordination

analyse,

reflect

Fig. 1. Teams and responsibilities in VPM

Each virtual team has its own goal, e.g., a sub-goal of the main goal given to co-

ordination team. The VPM collaboration between virtual teams can be planned in

advance (e.g., joint tasks) or during the process by co-ordination team. It may also

occur emergently as a need arises.

Facilitators and the research team have a close relationship and aim at making

sense of work processes and team behavior in the exercise and to develop means for

data analysis. Research team studies what takes place in the exercise and how people

experience the work. It analyses each team and gives the results as feedback to them.

2. inter-team

3. intra-team

1. facilitation

Co-ordination team

and manager

(Virtual)

teams with

managers

facilitators

Fig. 2. Communication paths in VPM

Figure 2 shows the main communication layers and participants in each layer.

Communication in the first layer, that is facilitation, takes place between facilitators

and the manager of the co-ordination team. The second layer tackles inter-team

communication and takes between co-ordination team (nominated members) and

virtual projects (managers). The third layer is inter-team communication that takes

place among team members. All communication can be made transparent using a

team discussion forum.

94

We claim that without such a structure the roles of each party remain unclear and

can even harm the progress of the exercise. We believe that leaving the appropriate

co-ordination and decision-making responsibility for each layer has a facilitatory

effect on the team commitment.

2.2 Co-ordination processes and mechanisms

We use the co-ordination theory by Malone and Crowston [9] and the concept of “co-

ordination mechanism” by Schmidt and Simone [17] to discuss how co-ordination in

VPM is planned.

Malone and Crowston define co-ordination as “management of dependencies

between activities”. This includes an assumption that if there is no interdependence

there is nothing to co-ordinate. It is clear that actors performing interdependent

activities may have conflicting interests. The goal in VPM has been to delegate tasks

and responsibilities to students. The dependencies of VPM can be pre-defined by

facilitators, left as a responsibility of the co-ordination team, or to take place

emergently between teams. Teams themselves decide practices for their intra-team

level collaboration, which often leads to an agreement by discussion (see e.g. [19]).

Malone and Crowston [9] identified four following dependencies:

Task/subtask relationships.

When a set of activities are all subtasks for achieving

an overall goal they need to be integrated either through top-down goal

decomposition or through bottom-up goal identification. In VPM each team has its

own predefined goal. Facilitators and co-ordination team discuss the goal

decomposition. The main responsibility of task accomplishment is given to the co-

ordination team. The clarification of sub-goals requires also negotiation and

agreement between co-ordination team and virtual teams. At any milestone, co-

ordination team reviews the deliverables of each virtual team and checks

dependencies (e.g. conflicts in interfaces).

Relationships between producers and consumers.

This dependency occurs when

one activity produces something that is used by another activity. It requires the

sequencing and transfer of products, and ensuring their accessibility from the

perspective of the receiving activities. This dependency is an essential part of VPM.

The learning stresses negotiation skills for arriving at an agreement between teams.

The number of interfaces between teams determines the degree of difficulty.

Simultaneity constraints. Activities need to occur at the same time. This type of

dependency requires synchronizing of activities. In VPM the synchronization of

activities is arranged using a set of milestones. The synchronization need is due to

producer-customer dependencies discussed above.

Management of shared resources.

Whenever multiple activities share a limited

resource (e.g. person, deliverable, or tools) a resource allocation process is needed to

manage the interdependencies among these activities. VPM focuses on a fluent

communication instead of creating bottleneck roles (communication layers). Most

tools and data are available for all (all the time) videoconferencing time as an

exception.

A certain coordination mechanism can be embedded in dependencies between

teams or as a part of team co-working. Schmidt and Simone [17] define co-ordination

mechanism as a construct of a coordinative protocol (an integrated set of procedures

95

and conventions such as a review, a contract negotiation or a follow-up) and a related

coordination artifact in which the protocol is objectified (minutes of a meeting, a

contract and a status report as examples). Coordination mechanism reduces the

complexity of the dependency and the space of possibilities. Because students learn to

use their own conceptualizations, VPM protocols embody weak stipulations [see 15].

2.3 Reflection processes

A special emphasis on reflection processes is included into VPM. A research team has

been formed in order to augment the traditional feedback given by facilitators and

self-reflection of students. A central part of the research is the utilization of 4Q

framework which provides a holistic view to study distributed work [10]. Bartlett and

Ghoshal [1], for example, have recently noted the importance of human and

intellectual capital and people as key strategic resource of building competitive

advance. This has also been our focus of interest and it has been studied from four

viewpoints:

Personal work focuses on issues around personal tasks of an individual in a

distributed environment. This area covers the following issues: competencies, mental

frameworks, motivation, stress, personal ambitions, individuality, working style,

beliefs, and values. Work with people focuses on general social interactions that,

firstly, take place between persons not having a close or formal relationship, and,

secondly, are often affected by organizational culture, traditions, values, and

experiences. For example, various communities belong to this category. Personal

goals, needs and earlier experiences are often driving forces for collaboration.

Project/teamwork focuses on how people are involved with production as a member

of projects and teams. Here, project goals are controlled and schedules are often tight.

In this area personal values and capabilities are considered against project rules,

processes, schedules, managerial styles and the values of closest teammates. The

fourth viewpoint focuses on the work with data and information. It addresses

capabilities of a person to use and utilize data and information [5]

1

including qualities,

means, and tools.

3 Applying the virtual project model in two seminars

This section presents two seminars applying VPM model. We describe the

arrangements and main differences of the seminars, show the evolution of the co-

ordination layer, and present our experiences and results of analyses.

1

We prefer to use data and information instead of knowledge. Any of the four areas may be

present in knowledge creation processes.

96

3.1 “Coaching model” (Spring 2003)

Virtual Project Model was first applied as a joint exercise between three different

seminars and units: Organizational Psychology (University of Helsinki), IS Project

Management (Helsinki School of Economics), and Knowledge Management

(Tampere Technical University). Altogether there were 49 students participating the

exercise with largest representation from economics. The participants had extensively

variable backgrounds ranging from second year students to those having a several

year experience in work life.

We had a leading facilitator from each university (with assistant facilitators), a

coaching team (7 persons), eight virtual teams and one local “reference” team (4-6

persons per team), and a research team (3 persons). Facilitators delegated the

following responsibilities to the coaching team: collecting a project management

literature database, providing coaching services and consultancy for teams, and

steering the progress and preventing problematic situations of teams.

All virtual teams and local teams were given the same goal of designing a

competence information system (CIS) that will be implemented in a fictional

organization. The process was divided into three sequential tasks:

1. Team identification and project planning (2 weeks)

2. Definition of system requirements and use scenarios (4 weeks)

3. System design and deployment planning (5 weeks)

The following tools were used: learning environment called Optima [3] as a shared

repository and a bulletin board, IP based videoconferencing tools in milestones, and

e-mail and phone for team communication.

A special topic of interest was the virtual start up of teams. We started each period

by giving instructions virtually through the Optima. The first task included a virtual

kick-off and team building. We composed teams, nominated the first project

managers and published the information via Optima. Teams were encouraged to use

available tools for their collaboration instead of meeting face-to-face. The first two

milestones were arranged as a multi-point videoconference, status checks and internal

reviews of deliverables (project plan, requirements specification) as tasks. In the last

session all teams presented their final report of CIS design.

3.2 “Subcontracting model” Fall 2003

The second exercise was arranged together with two seminars from the previous case

“Organizational Psychology” and “IS Project Management”. Altogether there were 36

students, 70 % of them from economics. The following teams were set up: a co-

ordination team (8 persons), five subcontractor teams (4-6 persons in each) and a

research team (5 persons). Next we consider changes and their motivation to the

earlier exercise covering team responsibilities and goal decomposition, kick-off, and

tools used.

The main goal for the exercise was still to design a CIS. But now the coaching

dependency was replaced by co-ordination dependency. The responsibilities of the co-

ordination team were as follows: to be an intermediary between facilitators and sub-

contractors (as in Figure 1), to guide sub-contractors work, and to follow-up teams’

progress. Co-ordination team created the imaginary organization and stated

97

requirements for CIS. They reviewed project plans of subcontractors, signed contracts

with them, steered the progress and accepted design reports. All subcontractors had a

sub-goal to design a part of the CIS (system architecture, database design, user

interface, and two system modules). The responsibility of use scenarios (a part of task

2 in earlier case) was given to the subcontractor designing general UI.

The kick-off was now organized differently. First, all students had the possibility to

select which team to join. Facilitators held a meeting with the co-ordination team in

which the responsibilities were discussed. After the meeting the exercise proceed

mainly as interplay between coordinators and subcontractors. Only minor questions

were asked from facilitators.

Optima was used as a shared repository, a discussion forum and a messaging tool

as in previous case. Now also Optima discussion lists were taken into use for inter-

team communication, for the negotiation and the acceptance processes. In addition,

teams used e-mail and phone for inter-team communication. Videoconferencing

sessions were not arranged.

3.3 Discussion of co-ordination and reflection processes

In the first exercise (“coaching model”) the main focus was to study and learn virtual

work and virtual start-up. We expected a need for coaching services but started with a

simple arrangement without dependencies between teams, all teams designing CIS. In

this exercise the role of the coaching team remained unclear due to minimal demand

for coaching. We believe two reasons affected to the lack of this demand. Firstly,

joined tasks were not planned to occur between teams. Secondly, the process was

divided into three tasks, and teams expected feedback and instructions to continue

from facilitators. Teams reported that without planned milestones their interest was in

their own responsibility and not in to design the whole CIS.

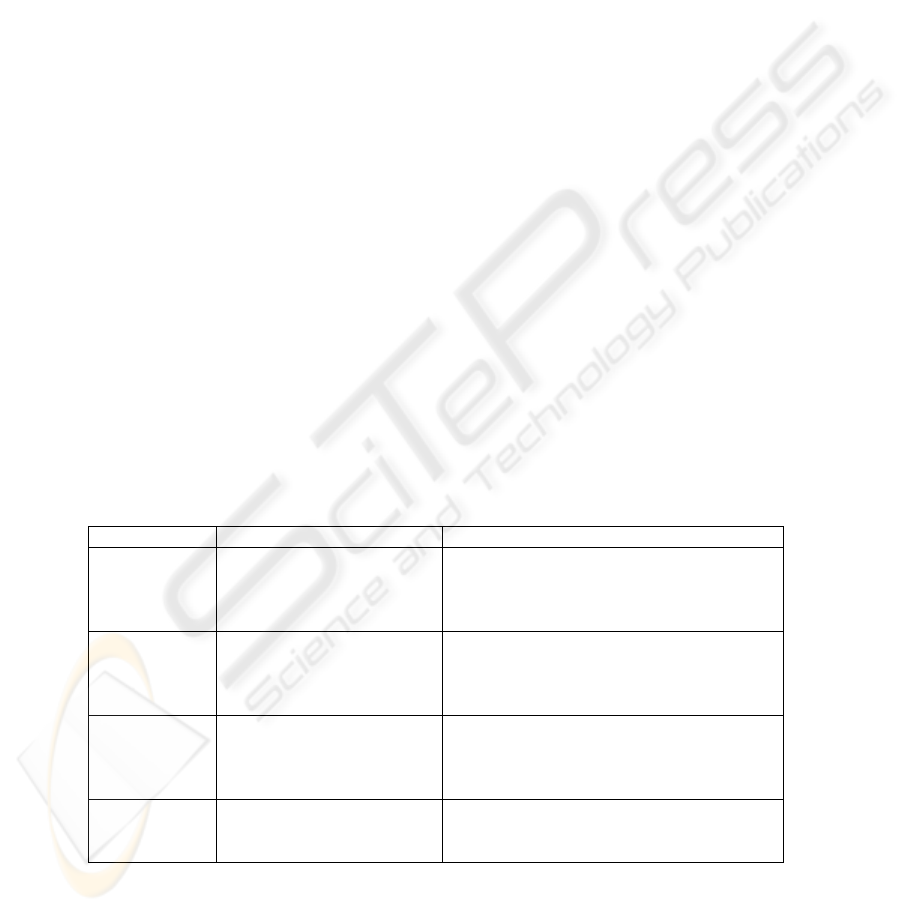

Table 1. Coordination in exercises: coordination dependencies, mechanisms (M) and artifacts

(A)

Dependency “Coaching model” “Subcontracting model”

Task-subtask

relationships

Intra-team coordination (M)

Project plan (A)

Goal decomposition by co-ordination team

(M), Statement of work (A)

Intra-team coordination (M), Project plan

(A)

Producer-

consumer

relationships

Project phases (M)

Project plan (A)

The team is both a producer

and consumer.

Requirements and design made by different

teams (M), Contract and project plan (A)

Dependency management between co-

ordination and subcontracting teams (M)

Simultaneity

constraints

Milestone presentations at

intra-team level (A)

No simultaneity constraints

between teams.

Flexibility in schedules by co-ordination

team (M),

Progress report to coordination team (A)

Shared

resources

“Coaching” aid (M) Interfaces between teams (M)

Requirements documentation and FAQ (A)

Discussion list per dependency (A)

98

The coaching dependency was not totally unrealized. Coaching team used their

role in two cases. Firstly, one of the teams did not start during the virtual kick-off and

this required the re-allocation of students. As a result two projects joined together.

Another case was a team conflict. Team members of diverse background had different

opinions of quality of deliverables. Based on the experiences we concluded to have

more emphasis on co-ordination in the “subcontracting” exercise. Table 1 summarizes

how co-ordination is arranged in two exercises.

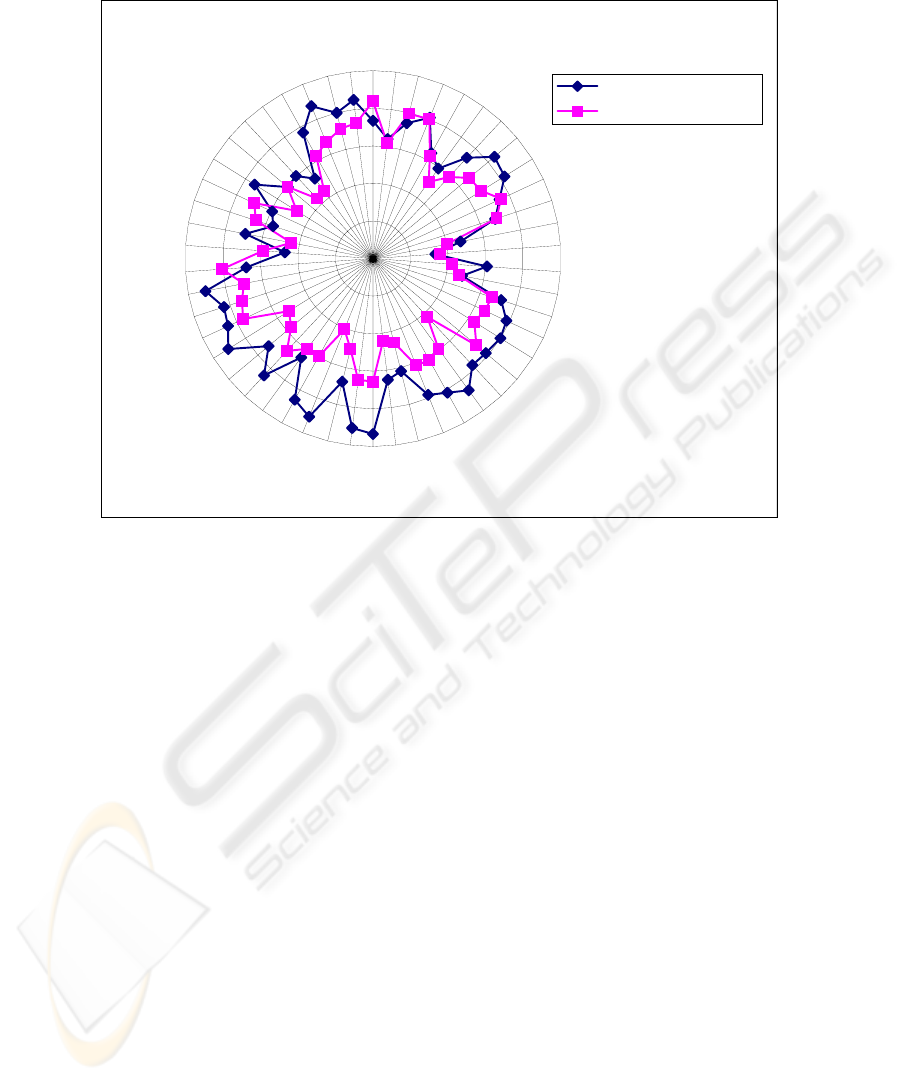

The research team used the 4Q framework for creating a questionnaire of 50

questions that monitored collaboration. We used 5 point Likert -scales, where the

anchors for the scales are: 1 = very low and 5 = very high. For the “coaching model”,

the study was done three times (4th week, 7th week, 10th week). The subjects were

instructed to use their earlier responses as a reference in order to guarantee within-

subject reliability. All 49 participants responded to the first survey, 47 to the second,

and 42 to the last one. Research team made an analysis for all teams and presented the

main findings of each teams. For the “subcontracting exercise” the test was

accomplished only at the end of the exercise (last week, 24 responses out of 33) and a

special feedback session was arranged.

We first summarize some findings of the coaching model with 8 virtual teams and

two local teams (including co-ordination team). After the virtual kick-off we

encouraged teams to proceed virtually but meeting face-to-face was not totally

forbidden. As we noted the virtual start-up was problematic for some teams. Another

disturbing factor was team members belonging to the same class and seeing each

other e.g. during courses. Thus, in addition to making a comparison between “virtual”

and local teams we compared persons working virtually with those working in a

mixed mode.

The overall profile of work in the exercises can be characterized by the following

data. 60% of time on average was spent working alone with assigned tasks.

Participants in local teams reported lower share for working alone. Presumably, they

could contribute to the tasks also during their meetings. It also seems that the amount

of face-to-face meetings was not essential for successful collaboration due to slight

differences between “virtual” and local teams. Semi-virtual teams met once in three

weeks and local ones once in two weeks. Probably the crucial factor was that teams

met or there was a possibility to meet when necessary.

One quarter of participants worked virtually, the rest met once per week or rarely

as discussed above. Virtual ones felt that they got less information from project and

other teams, and also were less satisfied with received feedback when compared

against others. However, they felt easier to share their work with others’ and also to

use others’ work. Furthermore, they felt better able to fit project goals and schedule to

their own ones.

99

Fig.3. Questionnaire results visualized as 4Q radar: means of two exercises.

The analysis of the subcontracting exercise is still ongoing and no final conclusions of

differences between two exercises have been done. However, as we expected from the

subcontracting model, the students were committed to the subcontracting course (they

gave the average score of 4.04 on a 5 point Likert scale in the 4Q test on this issue).

They also experienced the new arrangements (Section 3.2) as helpful. When

comparing means of respondents (Figure 3) we may assume to affect teamwork by

changing co-ordination. Differences in the area of “work with people” can be

interpreted as increased inter-team coordination in subcontracting exercise.

4 Conclusions

In organizing virtual collaboration and learning initiatives, there is no ready-made

knowledge of all factors (organizational, team-related, or individual ones) that come

to play in different contexts. We argue that this knowledge is partly tacit and we

consider useful to incorporate one type of research and/or monitoring function to

gather relevant knowledge and experiences from virtual work. This is especially

important in the early phases of projects. Often when projects are terminated the

obtained experiences are soon lost and there is a fast disruption of any shared

knowledge concerning the issues. The Virtual Project Model demonstrates a way to

0

1

2

3

4

5

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

subcontracting model

coaching model

Personal work

Work with people

Work with data

and information

Team work

100

study and to understand these problems. Our experiences from two seminars are quite

positive and the research data and other feedback that we received was very

constructive for developing the model further.

This study does not give answers to the questions of the best way to build co-

ordination or reflection. Based on our experiences we can say that if the pedagogical

aspects are not planned or are a free aspect of the tasks they will not be realized. We

see the layers of co-ordination and reflection as a way to support these pedagogical

aspects. The whole exercise is built on the action towards the goal and on interaction.

Thus, the role of an individual student needs to be well defined and clear enough in

the network of teams and layers.

As a next step in VPM we do statistical analyses of the data collected from two

seminars, study the capabilities of students to work in each exercise and analyze

differences between seminars. As we have developed a more coherent co-ordination

layer after the first attempt, our own goals are to improve learning practices for the

seminar. Secondly, based on the experiences we are ready for testing the exercise as a

multi-cultural and organizational exercise.

References

1. Bartlett, C.A. and Ghoshal, S. Building Competitive Advance Through People. MIT Sloan

Management Review, Winter, (2002), 34-41.

2. Cross, R., Nohria, N., and Parker, A. Six Myths about Informal Networks. MIT Sloan

Management Review, Spring 2002, (2002).

3. Discendum Optima. 2003, Discendum Oy www.discendum.fi

.

4. Fisher, K. and Fisher, M.D. The Distance Manager: A hands-on guide to managing off-site

employees and virtual teams. McGraw-Hill, 2001.

5. Galliers, R.D. and Newell, S. Back to the future: from knowledge management to the

management of data and information. Information systems and e-business Management, 1,

1, (2003), 5-14.

6. Hoefling, T. Working Virtually - Managing People for Successful Virtual Teams and

Organizations. Stylus Publishing, LLC, 2001.

7. Kimball, L. and Digenti, D. Leading Virtual Teams that Learn. 2001, Learning Mastery

Press: Amherst, MA. p. 43.

8. Lipnack, J. and Stamps, J. Virtual Teams: Reaching Across Space, Time and Organizations

with Technology. Wiley, New York, 1997.

9. Malone, T.W. and Crowston, K. The Interdisciplinary Study of Coordination. ACM

Computing Surveys, 26, 1, (1994), 87-110.

10. Marttiin, P., Nyman, G., and Lehto, J. Understanding and Evaluating Collaborative Work in

Multi-Site Software Projects - A framework proposal and preliminary results. In 35rd

Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences). IEEE, 2002,

11. McCreery, J.K. Assessing the value of project management simulation training exercise.

International Journal of Project Management, 21, (2003), 233-242.

12. Mills, A. Collaborative Engineering and the Internet. Society of Manufacturing Engineers,

1998.

13. Olson, G.M. and Olson, J.S. Distance matters. Human-Computer Interaction, 15, (2000),

139-178.

14. Raelin, J.A. A model of work-based learning. Organization Science, 8, 6, (1997), 563-78.

15. Renninger, K.A. and Shumar, W. Building Virtual Communities: Learning and Change in

Cyberspace. Cambridge University Press, 2002.

101

16. Rheingold, H. The Virtual Community: Homesteading on the electronic frontier. Addison-

Wesley, Reading: MA, 1993.

17. Schmidt, K. and Simone, C. Coordination Mechanisms: Towards a Conceptual Foundation

of CSCW Systems Design. Computer Supported Cooperative Work: The Journal of

Collaborative Computing, 5, (1996), 155-200.

18. Wenger, E., McDermott, R., and Snyder, W.M. Cultivating Communities of Practice: A

Guide to Managing Knowledge. HBS Press, 2002.

19. Winograd, T. and Flores, F. Understanding computers and cognition. Addition-Wesley,

Reading, MA, 1987.

102