ASSESSING THE USER ATTITUDE TOWARD PERSONALIZED

SERVICES

Seppo Pahnila

Department of Information Processing Science, University of Oulu, 90014, Oulu, Finland

Keywords: Personalization, personalized services.

Abstract: The fast growth of the Web has caused an excess of information to become available. Personalized systems

try to predict individuals’ behavior based on user information, in order to deliver more accurate and targeted

content by filtering out unimportant and irrelevant information. Prior personalization research has mostly

focused on e-business issues, personalization techniques and processes or privacy concerns. In this research,

we have studied users’ attitudes toward personalization and their desire to control personalized services. The

results are based on a field study consisting of 196 relevant responses from the users of a personalized

medical portal. We also analyzed respondents’ changes in attitude toward personalization by comparing

responses from two field studies. The results show that the respondents appreciate personalized information

which is closely related to their occupation. The respondents accept personalized services but they do not

consider automatic content personalization to be important, nor do they appreciate automatic appearance

personalization; they want to intervene in the transmitted information.

1 INTRODUCTION

The massive growth of available information on the

Internet has forced system owners to pay more

attention to easy access to the relevant information

at the right time. Users can get lost when navigating

in information space, or they might not find what

they are looking for (Brusilovsky 1996b).

Personalization tries to help individuals by reducing

the workload required to get relevant information at

the right time (Smyth and Cotter 2000).

Personalization has been implemented on the

Internet largely in two ways: by allowing the user to

customize personalized pages, or by allowing the

system to make the modifications. Customization

occurs when the user can to some extent manipulate

the interface, user profile or content manually

(Manber, Patel et al. 2000). In personalization, the

user has less control; essentially the system takes

care of content selection and presentation in a fully

automatic way, based on information from the user

model (Brusilovsky 1996b; Nielsen 1998; Kobsa,

Koenemann et al. 2001b). Individuals need for

control is guided their tendency to gain information

from the environment (Baronas and Louis 1988).

Individuals want to master their own acts and to

know the causes and consequences of their own and

others’ acts (Baronas and Louis 1988). Basically,

individuals are not willing to accept that they do not

have control. Nielsen (1998) doubts a personalized

system’s ability to predict user behavior. He

emphasizes that the user is the only one who knows

her/his needs. Nielsen places emphasis on user

control and the user’s right to make their own

choices. Conversely, Mulvenna (2000) suggests that

check box personalization, where users can select

pages they are interested in, is limited because users

cannot know the content of the IS in advance.

Brusilovsky (1996b) emphasizes that the question of

who will adapt the information is not merely a user

or system issue, it is dependent on the application

area.

Earlier personalization research has been mostly

focused on three areas: (e-)business issues (Riecken

2000; Schonberg, Cofino et al. 2000; Karat, Brodie

et al. 2003; Murthi and Sarkar 2003), personalization

techniques and processes (Resnick and Varian 1997;

Kramer, Noronha et al. 2000; Mobasher, Cooley et

al. 2000; Spiliopoulou 2000; Pierrakos, Paliouras et

al. 2003; Tam and Ho 2005) or privacy concerns

(Hoffman, Novak et al. 1999b; Volokh 2000; Kobsa

2002; Chellappa and Sin 2005). All these areas are

198

Pahnila S. (2007).

ASSESSING THE USER ATTITUDE TOWARD PERSONALIZED SERVICES.

In Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems - HCI, pages 198-206

DOI: 10.5220/0002351101980206

Copyright

c

SciTePress

linked with the service provider’s viewpoint to

personalization.

There are few studies which emphasize a “user-

centered” view of personalization. The objective of

this research is to focus on personalization as it

appears to the end users. Many features of

personalized Web information systems differ from

those of “traditional” information systems, and we

believe that this research can be expected to be of

interest to researchers, designers and companies that

employ personalized systems. In this research, we

have studied users’ attitudes toward personalization.

In particular, we address issues relating to users’

personalization expectations, experiences and their

willingness to control the personalized information

on offer. The users of the given information system

– a personalized medical information system – are

mostly doctors and medical personnel to whom it is

important to receive relevant, accurate and timely

information, for example, related to drugs, diseases

or methods of treatment. The main objective of the

IS is to provide access to special field information

and to facilitate the flow of information.

Personalization in a medical IS is designed for

certain particular groups with varying duties and

preferences by applying segmented personalization.

Segmentation is based on the speciality e.g. news

concerning anaesthesia is delivered to anesthetists.

Empirical data for the study was collected from

the users who are registered in the Finnish medical

network, and are users of the medical IS. Potential

users of the IS are geographically spread all over

Finland. We conducted a field study based on the

Web questionnaire with a result of 209 responses.

The total sum of reliable responses was 197.

Our findings suggest that people appreciate

personalized work-related information which is

closely related to their occupation. Moreover,

respondents accept personalization but they have a

desire to modify content themselves. Respondents

do not consider automatic content adaptation or

automatic appearance adaptation important.

The paper is organized as follows. In the

following section we will discuss, based on prior

literature, issues which may have an influence on

users’ attitudes toward personalized services. In

section 3 we describe the research methodology,

data collection procedures and the results of the

study. In the last section we draw conclusions from

the results of the study.

2 THEORETICAL

BACKGROUND

Eirinaki et al. (2003) define personalization as “the

process of customizing the content and structure of a

website to the specific and individual needs of each

user, taking advantage of the user’s navigational

behavior.” Many researchers emphasize business

values, loyalty and active interaction – for example,

Zemke and Connellan (2001) suggest that

personalization adds to the value of a site and may

lead to better customer retention and loyalty. Mittal

and Lassard (1996) emphasize the social side of

personalization, defining personalization as “the

social content of interaction between service

employees and their customers.” This definition of

personalization includes the quality of interaction or

closeness between the service employee and

customers. The feeling of closeness is an important

issue in the real world, and also in the virtual world.

The interaction can range from cold and impersonal,

to very warm and personal (Mittal and Lassar 1996).

These definitions reflect the fact that there is a

principled disharmony between the assumed needs

of the user, the true needs of the user and the website

designer’s view on what is relevant (Mulvenna,

Anand et al. 2000).

Nielsen (1998) emphasizes the usability of the

personalized system. The system should allow the

user to decide what information (s)he needs by

offering several understandable options to choose

between, so that the user’s choice is easy. Nielsen

stresses that the system should offer sufficient

information to the user so that the user knows the

consequences of their choices. Nielsen does admit

that personalization can work in cases when the

environment is stable and can be easily described in

the system. Nunes and Kambil’s (2001) findings are

consistent with the previous suggestions. In their

survey, they allowed customers to use services

which were both customized and personalized. Their

results indicate that customers clearly prefer

customized services. Nunes and Kambil concluded

that the best strategy might be to combine the two

techniques by allowing customers a certain degree of

control over an automatic personalized system.

3 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

We performed a field study in which data was

collected using a web questionnaire, which was

designed and developed in cooperation with experts

ASSESSING THE USER ATTITUDE TOWARD PERSONALIZED SERVICES

199

in the IT field and the target company. The scale

used was mainly the seven-point Likert scale, with 1

being the negative end and 7 the positive end

ranging from fully disagree to fully agree.

3.1 Demographic Profiles

Our target group was all the doctors and medical

students who are registered in the Finnish medical

network, and who are users of the medical IS.

Potential users of the IS are geographically spread

all over Finland. A field study with 209 responses

was conducted. The total sum of reliable responses

was 197. The potential number of IS users in total

was about 9500 including specialists, doctors,

medical students and the group “others”. Table 1

presents descriptive statistics of the sample.

Table 1: Profile of the respondents.

Measure Items Frequency Percent

Male 100 50.8

Gender

Female 97 49.2

≤ 31

51 25.9

32 - 41 53 26.9

42 - 51 46 23.4

Age

≥ 52

47 23.9

Specialist 112 56.9

Doctor 54 27.4

Occupational

title Medical

student/Other

31 15.7

Very/fairly

weak

13 6.6

Average 102

Fairly good 66 33.5

Computer

expertise

Very good 16 8.1

< 0.5h 64 32.5

less than 1h 81 41.1

1-5h 50 25.4

IS usage time

per week

5-10h 2 1.0

3.2 Usage of Different Services

We asked respondents to evaluate their usage of nine

most used services of the given system. The selected

services refer to different areas of interest: topics

related to expertise and work, and topics related to

study and leisure time. Table 2 shows responses that

indicate frequent use (often and very often used) of

the given services. We asked respondents to estimate

their activity using a five-point scale of

measurement ranging for never to very often. The

name of each service refers to a link, which is visible

on the portal’s page. The distribution of results

indicates that search services and special field news

are the most frequently used services. It is obvious

that respondents regularly follow the development,

e.g. research and science, of their profession.

Similarly, special field articles are considered

important.

Table 2: Usage of medical portal services.

Portal service Frequency Percent

Search services

55 28.2

Special field news

52 26.4

Leisure time services

(weather, news, etc.)

40 20.3

Special field articles

38 19.4

Special links

30 15.5

Drugs

23 11.8

Congresses

19 9.9

Forms

8 4.1

Ordering medical products

7 3.6

More leisure-related services, as weather and news

were also popular among regular users. “Forms”

includes, among others, different precompleted

forms, which the respondent need concerning their

work.

3.3 Respondents’ Behavior toward

Personalization Expectations

Personalization expectations were studied by setting

three questions which started with “Would you

like…”, and using a three-point scale, with the

options “No”, “I don’t know” and “Yes”. First we

asked the question “Would you like the medical

portal to adapt automatically according to the

services you have used?” Primary goal of these

questions was to assess users’ expectations towards

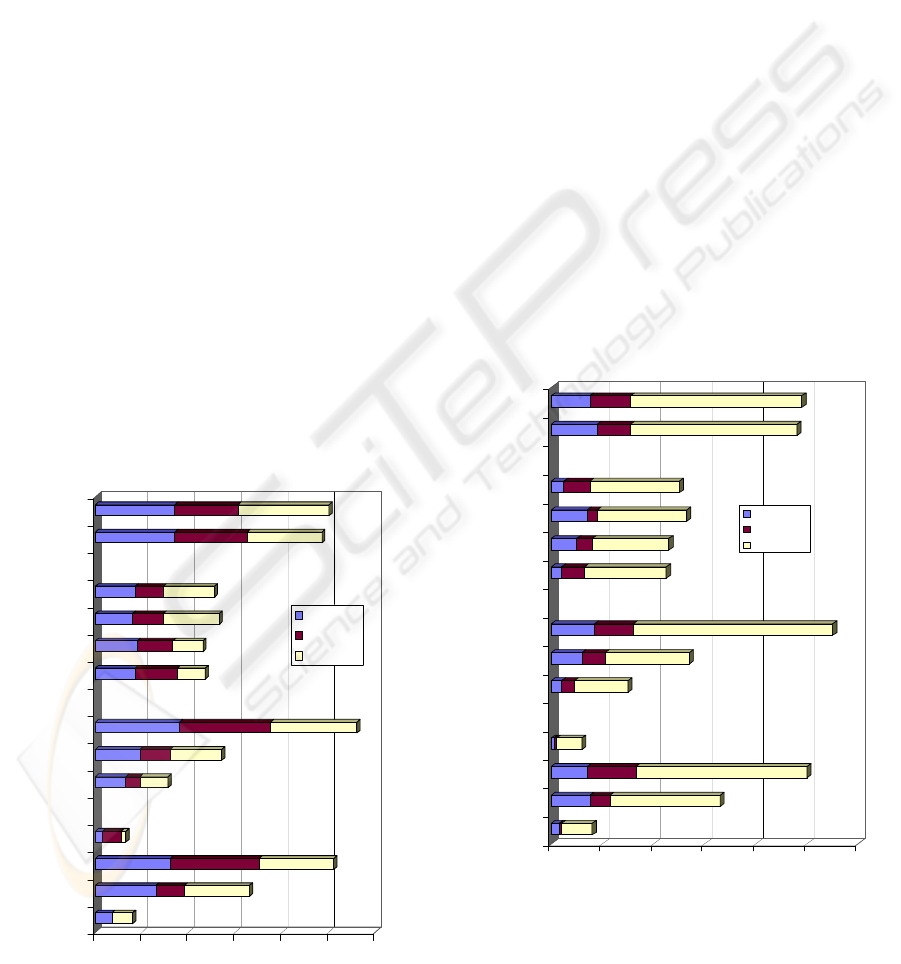

services. Figure 1 shows that, in general, the

responses were quite uniformly distributed between

“No” and “Yes”. The number of “Don’t know”

responses was also quite high. As Figure 1 shows

there was a slight difference between males and

females. The majority (39 %; N=39) of the male

respondents answered “Yes”, and 34 % (N=34)

answered “No”. Similarly 35.1 % (N=34) of females

answered “No” and 34.5 % (N=32) answered,

“Yes”. In age group there was a slight difference

between the groups that are under 41 and those 42

and over. According to cross tabulation followed by

a Pearson Chi-Square test, there was an association

between the variables expertise and automatic

ICEIS 2007 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

200

adaptation; hence automatic adaptation is dependent

on expertise. (χ

2

-value = 20.567, p-value = 0.002).

This conclusion was not necessarily reliable because

33.3 % of expected frequencies were less than five

(allowed maximum 20 %) and the expected

minimum was 3.83 (maximum more than 1).

Therefore, the difference was also tested using

Fisher’s Exact test (Fisher’s Exact test value =

21.438; p-value = 0.001). The tests indicate that

respondents’ attitude towards automatic

personalization is statistically significant and

dependent on expertise. Surprisingly, respondents

with fairly good or very good expertise would like

automatic personalization more than respondents

with weak or average expertise. Even though the

differences between these expertise groups are quite

minor, one would think that people with good

expertise would like to adapt and control the system

themselves more than respondents with weak

expertise. According to our analysis, there were no

differences between the groups in other

combinations.

Overall, considering the whole data, statistical

distribution show that 34.5 % (N=68) of the

respondents responded “No” to this question, 29.4 %

(N=58) answered “Don’t know” and 36 % (N=71) of

the respondents answered “Yes”. Thus, “No” and

“Yes” responses toward automatic adaptation were

quite equally distributed; respondents’ opinions

about the question was quite neutral.

70 9

26 12 28

32 38 32

382

13 6 12

19 13 22

36 39 37

17 18 12

18 15 13

16 13 24

17 12 22

34 31 32

34 27 39

0 20 40 60 80 100 120

Male

Female

<=31

32-41

42-51

>=52

Specialist

Doctor

Medic/other

Very/fairly weak

Average

Fairly good

Very good

No

Don't know

Yes

Figure 1: Respondents’ expectations regarding automatic

personalization.

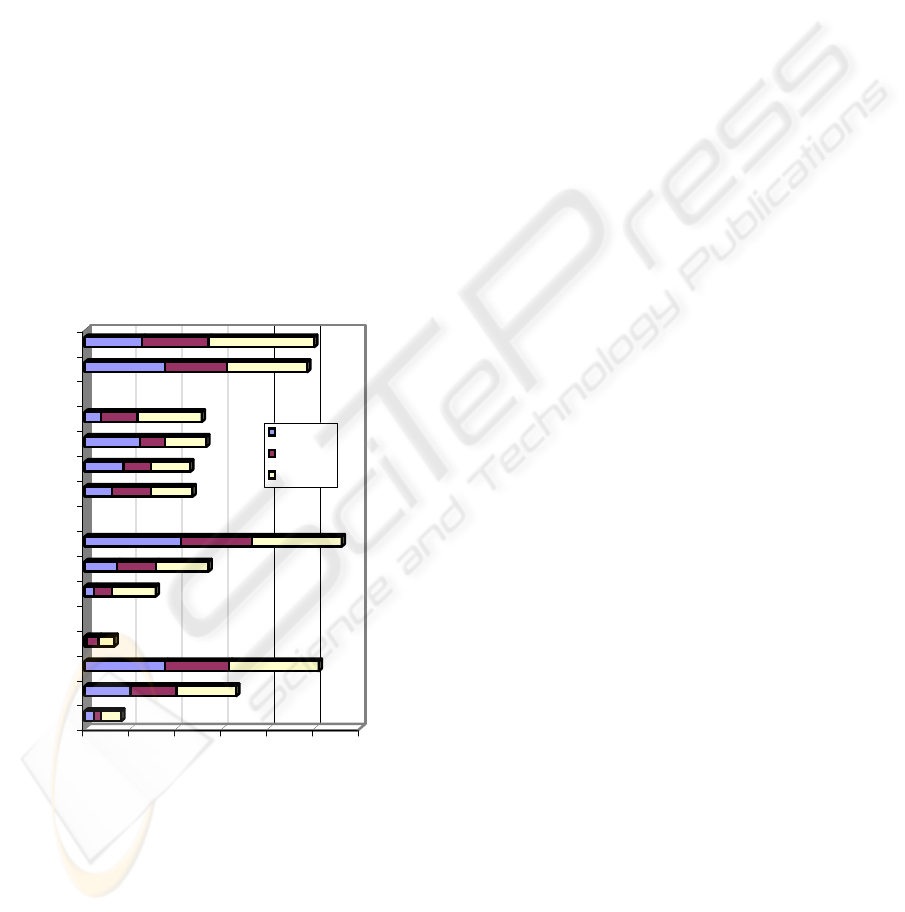

Secondly, we asked the respondents the question

“Would you like the most regularly-used services

concerning your special field to be displayed?”

Figure 2 shows that the majority of respondents

agree that the most regularly-used services related to

their special field should be on view. Moreover,

most of the respondents, who answered “Yes” were

specialists and they assessed their computer skills as

average. This may indicate that willingness to

receive information increases if the respondent feels

that the information on offer is related to their work

and tailored to their work requirements. On the other

hand this may indicate that respondents rely on

collaborative recommendations; they use the same

services as their colleagues have used. According to

cross tabulation followed by a Pearson Chi-Square

test there was no association between the variables

gender, age, occupation, expertise and displaying the

most regularly-used services concerned to own

special field.

Thirdly, we asked the respondents: “Would you like

the most regularly-used services of all special fields

to be displayed?” Figure 3 shows that some

respondents in different classes would appreciate the

most regularly-used services of all special fields

being displayed.

31 12

15 8 43

14 19 67

1110

45 21

12 9 33

17 15 78

49 32

10 6 30

14 4 35

510 35

18 13 65

15 16 67

0 20 40 60 80 100 120

Male

Female

<=31

32-41

42-51

>=52

Special

Doctor

Medic/other

Very/fairly weak

Average

Fairly good

Very good

No

Don't know

Yes

Figure 2: Respondents’ expectations concerning the most

regularly-used services relating to their special field.

However, the degree of interest is clearly lower

than in the previous case (Figure 2). It is interesting

that in some classes the results were negative. For

ASSESSING THE USER ATTITUDE TOWARD PERSONALIZED SERVICES

201

example, in the age group 32-41 most of the

respondents (N=24) would not like these services to

be displayed. Similarly, most of the specialists

(N=42) would not like the most used services to be

displayed. The results below confirm the finding that

respondents are more interested in tailored services

which are related to their job and familiar to them.

Cross tabulation analysis followed by a Pearson

Chi-Square test indicated that there was association

between the age group and the displaying the most

regularly-used services of all special field (Pearson

χ

2

-value = 15.160, p = 0.019). There was also

relationship between the group occupation and

question posed (Pearson χ

2

-value = 9.775, p = 0.044)

and the expected frequencies were 0%, expected

minimum 8.81. According to our analysis there was

no relationship between other combinations.

Considering the figures, Figure 2 and Figure 3,

respondents hope for easy and quick access to

personalized work-related information, and clearly

appreciate depth of information (their own special

field) more than breadth of information (all special

fields).

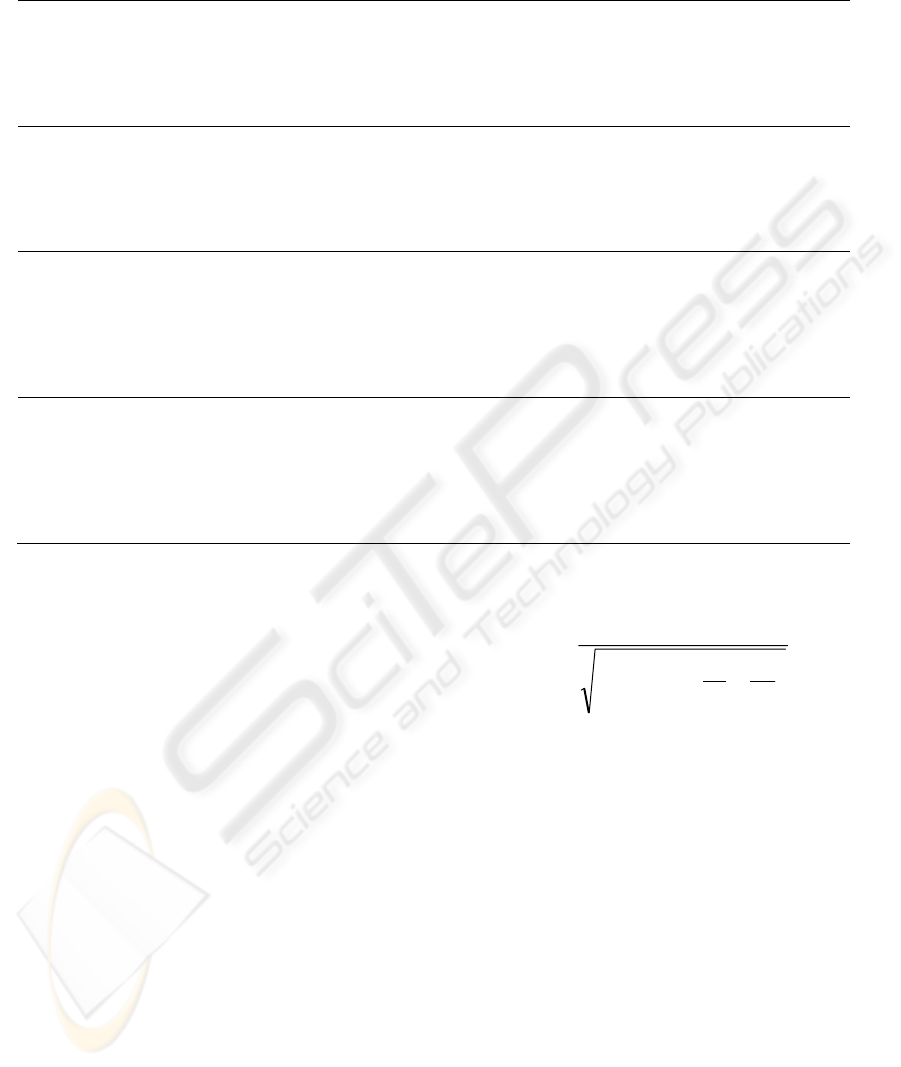

43 9

20 20 26

35 28 39

15 7

48 19

14 17 23

42 31 39

12 17 18

17 12 17

24 11 18

716 28

35 27 35

25 29 46

0 20 40 60 80 100 120

Male

Female

<=31

32-41

42-51

>=52

Specialist

Doctor

Medic/other

Very/fairly weak

Average

Fairly weak

Very weak

No

Don't know

Yes

Figure 3: Respondents’ expectations concerning the most

regularly-used services relating to all special fields.

3.4 Respondents’ Attitude toward

Personalization

The analysis described in this section is twofold.

First we analyze the differences between the selected

groups toward the presented hypotheses by using T-

tests and analysis of variance. Secondly, we assess

responses to the presented hypothesis, from all of the

data.

Respondents’ attitude towards personalization

were studied by setting four hypotheses starting with

“In my opinion…”, using Likert seven-point scales

where 1 was “fully disagree”, and 7 “fully agree”.

The hypotheses below were aimed at examining the

users’ willingness to be involved in the

personalization process; that is, whether they want to

personalize the system themselves, or have

automatic personalization carried out by the system.

We were also interested in respondents’ attitude

towards personalization objects: whether the

respondents like to personalize layout and/or content

or not. For example, respondents’ attitude towards

carrying out layout adaptation themselves was

examined by setting the hypothesis “In my opinion,

it is important that I can make the site more personal

by editing the appearance (layout) of the service,

such as the color of the display”.

The selected variables we were interested in

included gender, age, expertise and occupation. In

the case of gender, we analyzed the responses by

using a T-test. By using Levene’s T-test, we

confirmed that the variances were equally

distributed. The results in Table 3 show that there is

not a significant difference in attitude toward

personalization between the appearance of the

service, content and gender The significance of the

variables age, occupation and expertise were tested

using one-way analysis of variance (One-Way

ANOVA). According to analysis there are no

significant statistical differences between in the

attitude toward personal adaptation of site layout and

the age, occupation and expertise groups. However,

in the expertise group F(3.193)=2.266, p=.082, it

seems that respondents with better computer

expertise are more willing to adapt the layout

themselves than respondents with weak expertise.

This may indicate that users with higher expertise

may have stronger beliefs concerning their abilities

and skills needed to execute the tasks ahead than

users with weaker expertise. Overall, considering the

whole data statistical distribution show that, 45.7 %

(N = 90) of the respondents have a negative (fully

disagree, disagree, disagree to some extent) attitude

regarding user adaptation of layout, 15.2 % (N = 30)

answered “Don’t know” and 39.1 % (N = 77) have a

positive (agree to some extent, agree, fully agree)

attitude toward the hypothesis. Total N = 197, mean

3.80 and standard deviation 1.521. Thus, most of the

respondents do not consider the option to adapt the

appearance of the site themselves to be important.

ICEIS 2007 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

202

Table 3: Gender distribution regarding adaptation of layout and content.

Attitude toward personalization Gender N Mean Std. Dev t value Sig

In my opinion, it is important that I

can make the site more personal by

editing the appearance (layout) of

the service, such as the color of the

page.

Male

Female

100

97

Total

197

3.99

3.61

1.617

1.396

1.771

1.775

.078

In my opinion, it is important that I

can make the site more personal by

adapting the content of the service,

such as by selecting and deleting

content according to my own

preferences.

Male

Female

100

96

Total

196

4.46

4.23

1.540

1.395

1.098

1.100

.273

In my opinion, it is important for

the site to become more

personalized automatically

according to my usage, by adapting

the appearance (layout) of the

service, such as the color of the

page.

Male

Female

99

95

Total

194

3.75

3.39

1.561

1.339

1.711

1.717

.089

In my opinion, it is important for

the site to become more

personalized automatically

according to my usage, by adapting

the content of the service, such as

by selecting and deleting content

according to my own preferences.

Male

Female

100

97

Total

197

3.78

3.73

1.541

1.425

.227

.227

.821

3.5 Attitude toward Personalization:

Comparison between Two Field

Studies

The objective of this section is to compare

respondents’ responses from two field studies. Time

period between the studies was about one and a half

year. Respondents of the field studies were the users

of same personalized IS. In both studies the data was

collected using a Web questionnaire. The questions

that we are interested in were identical in both field

studies, and related to the desire for automatic

personalization and the level of available

personalized information. We carried out the

comparison by studying the differences between the

“Yes” and “No” responses, taking into consideration

male responses, female responses and total

responses.

A two-sample Z-test of proportion was used on

the study1 and study2, to reveal differences in

respondents’attitude toward personalization. The

statistical formula used in the two-sample Z-test for

proportion to compute the Z-test statistic (Vasama

and Vartia 1973; Zou, Fielding et al. 2003) can be

presented:

p

c

= (x

1

+ x

2

)/n

1

+n

2

, and the test statistic Z can be

presented:

Z =

)

11

)(1(

21

21

nn

pp

pp

cc

+−

−

,

where the observed numbers of successes are p

1

=

x

1

/n

1

(relating to the study1) and p

2

= x

2

/n

2

(relating

to the study2). x

1

(the study1) and x

2

(the study2) are

the numbers of successes and n

1

(the study1) and n

2

(the 2 study2) are the sample sizes.

When the test statistic Z is normally distributed,

the interpretation of statistical significance is based

on the location of the p- value within the normal

distribution table (Herva, Vartia et al. 1983) of Z.

Null hypothesis assume that there is no difference

between the group gender and in attitude toward

adaptation compared with the study1 and study2.

The null hypothesis is rejected at the significance

level p<0.05 if the test statistic Z exceeds the critical

values below –1.96 or above +1.96.

In study1, the number of relevant responses was

144. The number of male respondents was 87 and

female respondents 57, ranging from 22 to 67 years

of age. The majority of the respondents (56.3 %)

belonged to the age group 30-50 years of age. Most

ASSESSING THE USER ATTITUDE TOWARD PERSONALIZED SERVICES

203

of the respondents (64 %) were medical students,

followed by the groups “specialist” (10%), “other”

(24%) and “researcher” (2%). The results of the two-

sample Z-test of proportion are presented in Table 4.

With regard to the first question, Table 4 shows that

there is a significant difference (p

≤ 0.01), when

comparing all the responses, between the study1 and

the study2. There is no difference in the attitude of

the male respondents, whereas there is a significant

(p

≤ 0.01) difference in the “No” responses of the

female respondents between the study1 and study2.

As Table 4 shows, there are changes in female and

total groups in terms of the “Yes” and “No”

answers. In study1, respondents’ opinions about

automatic adaptation were more positive than in

study2. When the field study was conducted in

study1, the degree of personalization of the system

was not so sophisticated, therefore it could be that

respondents did not have a precise mental

impression of what adaptation or personalization

really means. Another explanation is, as shown

earlier, respondents with good expertise emphasized

automatic personalization less than respondents with

lower expertise. Thus in study2, respondents were

more familiar and skilful with the system, and they

were more able to interact with the system.

With regard to the second question, there are no

significant differences between responses in the

study1 and study2. Generally, changes in behavior

over a one and a half year period are minimal. On

the other hand, when considering the third question,

there are significant statistical differences in the

male group both in “Yes” responses (p

≤

0.05) and

in “No” responses (p

≤

0.05), when comparing the

study1 and study2. There are also statistically

significant differences in female responses, both

“Yes” (p

≤

0.05) and “No” (p

≤

0.05). The most

important difference is in total responses; both

“Yes” (p

≤

0.001) and “No” (p ≤ 0.001) are

statistically very significant. The direction of the

change is consistent with the first question. In

study1, respondents’ attitude toward the most-used

services of all special fields was more positive than

in study2. Considering the two preceding questions,

these findings support the hypothesis that there exist

some changes in respondents’ attitude towards more

tailored and focused information services. It could

be that the as the flow of information is increasing

all the time, people are willing to think what kind of

information they are willing to receive.

Table 4: Two-sample Z-test of proportion.

Question Gender

Resp

onse

x

1

n

1

p

1

x

2

n

2

p

2

Z

Male Yes 41 81 .506 39 100 .390 1.565

Female Yes 27 56 .482 32 97 .330

1.864*

Total Yes 68 137 .496 71 197 .360

2.479*

Male No 20 81 .247 34 100 .340 -1.361

Female No 8 56 .143 34 97 .351

-2.773**

Would you like the

medical portal to adapt

automatically according

to the services you have

used?

Total No 28 137 .204 68 197 .345

-2.797**

Male Yes 56 82 .683 67 98 .684 -.011

Female Yes 39 56 .696 65 96 .677 .248

Total Yes 95 138 .688 132 194 .680 .154

Male No 9 82 .110 15 98 .153 -.851

Female No 6 56 .107 18 96 .188 -1.311

Would you like the most

regularly-used services

concerning your special

field to be displayed?

Total No 15 138 .109 33 194 .170 -1.568

Male Yes 50 82 .610 46 100 .460

2.013*

Female Yes 34 56 .607 35 97 .361

2.950**

Total Yes 84 138 .609 81 197 .411

3.559***

Male No 12 82 .146 25 100 .250

-1.729

Female No 8 56 .143 35 97 .361

-2.889**

Would you like the most

regularly-used services of

all special fields to be

displayed?

Total No 20 138 .145 60 197 .305

3.373***

*p

≤

0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p

≤

0.001

ICEIS 2007 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

204

4 CONCLUSION

In this research we focused on users’ attitudes

toward personalization and their willingness to

intervene in personalized services. Results show that

respondents with fairly good or very good expertise

would like automatic personalization more than

respondents with weak or average expertise. It could

be that respondents with good expertise would like

to control the system more than respondents who do

not have such advanced computer skills. Secondly,

our results show that respondents are willing to

receive information that is related to their work and

tailored to their work requirements. When

examining users’ willingness to control

personalization we formulate a hypothesis; would

users prefer to intervene in personalization or to

allow the system to take of care personalization?

Most of the respondents do not consider adapting

the appearance themselves to be important. When

analyzing the respondents’ willingness in terms of

content adaptation, the results indicated that most of

the respondents considered it important that they

could adapt the content themselves. Considering the

whole data, the results revealed that the respondents

have a negative attitude towards automatic

adaptation of site appearance. When analyzing

respondents’ attitude towards automatic content

adaptation, no differences were found between the

groups. When comparing the field studies study1

and study2, the findings revealed that respondents’

attitudes had changed. One significant change was

toward more tailored and focused information

services. Thus, users are looking primarily to use

services which are closely adapted to their

occupation.

The results of the study suggest that users do not

consider automatic content adaptation and automatic

layout adaptation to be important. Nor do they

consider it important to be able to adapt the layout

themselves. It was surprising that the users did not

set great store by the visual impact of the IS. This

shows that users appreciate content above visual

impact. This result gives support to the findings of

Kramer and Noronha (2000). Overall, the

respondents accept personalization but they want to

adapt and personalize the content themselves. It

could be proposed that designers and/or managers

should construct the user interface with an “opt-in”

function, determining whether the users would like

the system to provide personalized services or not. If

users want personalized services, there should also

be an opt-in concerning whether they would like

automatic personalization or to select interesting

topics themselves.

REFERENCES

Baronas, A. and M. Louis (1988). "Restoring a Sense of

Control During Implementation: How User

Involvement Leads to System Acceptance." MIS

Quarterly 12(1): 111-124.

Brusilovsky, P. (1996b). Methods and techniques of

adaptive hypermedia. User Modeling and user

Adapted Interaction. 6: 87-129.

Chellappa, R. K. and R. G. Sin (2005). "Personalization

versus Privacy: An Empirical Examination of the

Online Consumer's Dilemma." Information

Technology and Management 6: 181-202.

Eirinaki, M. and M. Vazirgiannis (2003). "Web Mining

for Web Personalization." ACM Transactions on

Internet Technology 3(1): 1-27.

Herva, A., Y. Vartia, et al. (1983). Tilastollisia taulukoita.

Helsinki, Oy Gaudeamus Ab.

Hoffman, D. L., T. P. Novak, et al. (1999b). "Building

Consumer Trust Online. How merchants can win back

lost consumer trust in the interests of e-commerce

sales." Communication of ACM 42(4): 80-85.

Karat, C. M., C. Brodie, et al. (2003). "Personalizing the

user experience on ibm.com." IBM Systems Journal

42(4): 686-701.

Kobsa, A. (2002). "Personalized Hypermedia and

International Privacy." Communication of ACM

45(5): 64-67.

Kobsa, A., J. Koenemann, et al. (2001b). "Personalized

hypermedia presentation techniques for improving

online customer relationships." The Knowledge

Engineering Review. 16(2): 111-155.

Kramer, J., S. Noronha, et al. (2000). "A User-Centered

Approach to Personalization." Communication of

ACM 43(8): 45-48.

Manber, U., A. Patel, et al. (2000). "Experience with

personalization on Yahoo!" Communication of ACM

43(8): 35-39.

Mittal, B. and W. M. Lassar (1996). "The Role of

Personalization in Service Encounters." Journal of

Retailing 72(1): 95-109.

Mobasher, B., R. Cooley, et al. (2000). "Automatic

personalization based on Web usage mining."

Communication of ACM 43(8): 142-151.

Mulvenna, D. M., S. S. Anand, et al. (2000).

"Personalization on the net using Web mining."

Communications of ACM 43(8 ): 123-125.

Murthi, B. P. S. and S. Sarkar (2003). "The Role of the

Management Sciences in Research on

Personalization." Management Science 49(10): 1344-

1362.

Nielsen, J. (1998). "Personalization is over-rated."

Retrieved 01.02.2001, from

http://www.useit.com/alertbox/981004.html.

ASSESSING THE USER ATTITUDE TOWARD PERSONALIZED SERVICES

205

Nunes, P. F. and A. Kambil (2001). "Personalization? No

Thanks." Harvard Business Review 79(4): 32-34.

Pierrakos, D., G. Paliouras, et al. (2003). "Web Usage

Mining as a Tool for Personalization: A Survey." User

Modeling and User-Adapted Interaction 13: 311-372.

Resnick, P. and H. R. Varian (1997). "Recommender

Systems." Communication of ACM 40(3): 56-58.

Riecken, D. (2000). "Personalized views of

personalization." Communications of ACM 43(8

(August 2000)): 27-28.

Schonberg, E., T. Cofino, et al. (2000). "Measuring

success." Communication of ACM 43(8): 53-57.

Smyth, B. and P. Cotter (2000). "A personalized television

listings service." Communication of ACM 43(8): 107-

111.

Spiliopoulou, M. (2000). "Web Usage Mining for Web

Site Evaluation. Making a site better fit its users."

Communication of ACM 43(8): 127-134.

Tam, K. Y. and S. Y. Ho (2005). "Web Personalization as

a Persuasion Strategy: An Elaboration Likelihood

Model Perspective." Information Systems Research

16(3): 271-291.

Vasama, P.-M. and Y. Vartia (1973). Johdatus

tilastotieteeseen osa II, Oy Gaudeamus Ab.

Volokh, E. (2000). "Personalization and privacy."

Communication of ACM 43(8): 84-88.

Zemke, R. and T. Connellan (2001). E-service. New York,

AMACOM, American Management Association.

Zou, K. H., J. R. Fielding, et al. (2003). "Hypothesis

Testing I: Proportions." Radiology 226(3): 609-613.

ICEIS 2007 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

206