The International Classification of Functioning,

Disability of Health as a Conceptual Framework for the

Design, Development and Evaluation of AAL Services for

Older Adults

Alexandra Queirós

1

, Joaquim Alvarelhão

1

, Anabela Silva

1

, António Amaro

1

, António

Teixeira

2

and Nelson Pacheco da Rocha

1,3

1

Escola Superior de Saúde, Universidade de Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal

2

Dep. Electrónica Telecomunicações e Informática / IEETA, Universidade de Aveiro

Aveiro, Portugal

3

Secção Autónoma de Ciências da Saúde, Universidade de Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal

Abstract. The paper presents the International Classification of Functioning,

Disability of Health (ICF) as a comprehensive model for a holistic approach for

the design, development and evaluation of Ambient Assisted Living (AAL)

services for older adults. ICF can be used to systemize the information that

influence individual's performance and to characterize users, theirs contexts,

activities and participation. Furthermore, ICF can be used to structure a

semantic characterization of AAL services and as a basis to develop

methodological instruments for the services evaluation.

1 Introduction

1.1 Active Ageing

Accordingly to World Health Organization (WHO) population ageing is one of

humanity’s greatest triumphs [1]. It is also one of our greatest challenges: the global

ageing is putting increased political, economic and social demands on all countries.

To overcome these pressures, WHO argues that governments, international

organizations and civil society should promote active ageing policies and

programmes.

The main goal of active ageing is the promotion of older adults in social,

economic, cultural, spiritual and civic affairs, while providing them with adequate

protection, security and care. The implementation of active ageing requires a strategic

planning based on a rights-based approach that recognizes the rights of people to

equality of opportunity and treatment in all aspects of life as they grow older and also

a positive thinking about enablement instead of disablement. We must be aware that a

disabling perspective increase the needs of older people and lead to isolation and

dependence, while an enabling perspective focuses on restoring functions and

expanding the participation of older adults in all aspects of society [1].

Queirós A., Alvarelhão J., Silva A., Amaro A., Teixeira A. and Pacheco da Rocha N..

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability of Health as a Conceptual Framework for the Design, Development and Evaluation of AAL

Services for Older Adults.

DOI: 10.5220/0003341700460059

In Proceedings of the 1st International Living Usability Lab Workshop on AAL Latest Solutions, Trends and Applications (AAL-2011), pages 46-59

ISBN: 978-989-8425-39-3

Copyright

c

2011 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

Active ageing depends on a variety of influences or determinants that surround

individuals, families and nations related with personal characteristics, culture and

gender, but also with societal characteristics and infra-structures (e.g. physical

environments, support services, economical and social determinants) [1]. In terms of

individual perspective, the three basic pillars of active ageing are [1]: full

participation in socioeconomic, cultural, spiritual and civic affairs, according to basic

human rights, capacities, needs and preferences; access to the entire range of health

and social services that address the needs and rights of older adults; and protection,

dignity and care in events that older adults are no longer able to support and protect

themselves.

The framework of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability of

Health (ICF) [2] is aligned with the enabling perspective of the active ageing and it

focuses on the individual participation independently of theirs health state.

1.2 International Classification of Functioning, Disability of Health

The ICF offers a framework for conceptualizing functioning associated to health

conditions [3] and it considers that are many factors that affect and have influence on

the individual’s performance and thereby on the decisions made on what type of

service is needed either delivered by care staff, relatives, aid appliances and

technology.

The ICF structure separates between the body, activities, participation and

contextual factors [2] as part of the individual's functioning. Additionally, it considers

the context (environmental factors and personal factors) as components that can

enhance or limit the performance, depending on how the individual experiences

limitations (e.g. due to possible weakness, illness and/or handicap). The structure is

illustrated in the Figure 1 [2].

Health Condition

(disorder / disease)

Body

(impairment)

Activities

(limitation)

Participation

(restriction)

Environmental

Factors

Personal

Factors

Health Condition

(disorder / disease)

Body

(impairment)

Activities

(limitation)

Participation

(restriction)

Environmental

Factors

Personal

Factors

Fig. 1. Interaction of ICF concepts.

Following there is a description of each of the ICF elements [2]:

− Activities - Activities are the individual’s recital of assignments and tasks.

Difficulties with these activities are noted as activity limitations. Limitations are

47

usually due to function depreciation of bodily functions but also due to

environmental hindrances.

− Participation - Participation covers the individual’s involvement in daily life and

society. Difficulties in participation are classified as participation restrictions.

− Body - The body's functions entail the individual’s physiological functions. ICF

defines disability as any problem of the individual with his/her bodily functions.

Physical functions depreciations can, in principle, have no consequences for the

individual's ability to do activities, especially if there are help aids that compensate

particular functions depreciation (e.g. an individual with weak eyesight wearing

glasses would not have a limitation.

− Contextual factors - The contextual factors are the environmental and personal

factors which either enhance or limit the individual's functioning. These factors are

indirectly understood in the sections of evaluation of activities and participation;

however, they are important to explain certain situations (e.g. two individuals with

the same diagnosis/ physical function depreciation may have different limitations

when it comes to activities and participation). The environmental factors are the

physical, social or attitudinal world ranging from the immediate to more general

environment. The personal factors entail elements that make people different and

unique, such as life style, education level, sex, race, life events or psychological

characteristics.

Differences in mastering capacity are a possible explanation to why individuals

with the same physical function depreciations do not have the same limitations when

performing various activities. For example, when it is windy outside, some

individuals will put up wind shelters, whilst others put up windmills. Dependent on

whether one looks upon changes as strenuous or as a challenge which contains new

options.

The environmental factors can have a positive (i.e. be facilitators) or negative

impact (i.e. be barriers) on the individual’s performance as a member of society, on

the individual’s capacity to execute actions or tasks, or on the individual’s body

function or structure. When coding an environmental factor as a facilitator, issues

such as the accessibility of the resource, and whether access is dependable or variable,

of good or poor quality, should be considered.

In the case of barriers, it might be relevant to take into account how often a factor

hinders the person, whether the hindrance is great or small, or avoidable or not. It

should also be kept in mind that an environmental factor can be a barrier either

because of its presence (e.g. negative attitudes towards people) or its absence (e.g. the

unavailability of a needed service).

The classification has individual items or codes defined within each chapter. The

ICF contains 1,424 codes organized according to an alphanumeric system. Each code

begins with a letter that corresponds to its component domain: b (Body Functions), s

(Body Structures), d (Activities and Participation) or e (Environmental Factors). The

letter is followed by between one and five numeric digits. Items are organized as a

nested system so that users can telescope from broad to very detailed items depending

upon the needs presented by particular applications of the ICF.

48

1.3 Living Usability Lab Project

Over the last decade, considerable research efforts have been pursued by the

European Commission, national governments and relevant industries to provide an

adequate technology response to the challenges of an ageing society [4]. In terms of

technology uses, the so called independent living or Ambient Assisted Living (AAL)

domain today comprises a heterogeneous field of applications ranging from quite

simple devices such as intelligent medication dispensers, fall sensors or bed sensors to

complex systems such as networked homes and interactive services. Some are

relatively mature and some are still under development.

Considering the growing importance of AAL services, the Living Usability Lab

(LUL) intends to develop AAL services to fulfill some needs that are common to

older adults: full participation in society, health and quality of life or living with

security.

Dependency is strongly related with the ability to perform Activities of Daily

Living (ADL). There are two groups of ADL: the basic ADL consist of those skills

needed in typical daily self care, namely personal hygiene, dressing and undressing,

eating or moving around; and instrumental ADL are skills that let an individual live

independently in a community, beyond basic self care, and that may include typical

domestic tasks, such as driving, cleaning, cooking, and shopping, as well as other less

physically demanding tasks such as operating electronic appliances or handling

budgets.

Basic ADL are out of the scope of the LUL since most of the times require the

caregiver intervention. The impossibility of perform instrumental ADL like

housekeeping (e.g. cleaning, cooking, shopping, or ironing) usually implies that the

individual needs help and although, in some circumstances, he/she can live alone,

although in border of the dependency. It is clear that AAL services can not supply

these needs completely but they can mitigate the effects by means of specialized

service (e.g. an e-commerce solution for shopping or a well managed external

housekeeping service) [5].

Additionally, AAL services can contribute to increase the older adults’

performance in a broad spectrum of activities and participation [5]: personal care,

planning of the weekly menu, nutritional advisor, maintenance of house and garden,

self administration or agenda; support in finding and carrying out work, establishing

and maintaining contacts with other people, and, in general, in spending the day

(through the participation in different leisure activities) and social integration

participation.

Furthermore, AAL services can contribute to the reorientation in health systems

that are currently organized around acute, episodic experiences of disease, namely, by

allowing the development of a broad range of services such as care prevention and

care promotion and home-caregiver support.

Some of the AAL services for older adults consider their users as people who are

weak and passively assisted by others [6, 7]. The position should be the opposite:

those services should help encourage the older adults to actively participate in society

(i.e. the enabling perspective of the active ageing paradigm). However, older adults

are usually scared by the application of new technology. Therefore, we should

construct user friendly interfaces, and also provide appropriate trainings to their users.

49

Developing adaptive, natural and multimodal human computer interfaces is the main

challenge of future interfaces in AAL [8]. This is the main goal of the LUL project.

2 Our Position

Taking in consideration the needs of the target users for the AAL services aimed by

our Living Lab and the state of the art, we defend that integration of a holistic view of

the individuals and their context is needed and has the potential for advantages in

terms of the adequacy of the services being developed.

The existence of a conceptual framework based on standardized concepts can

provide a common language between strategic planners, technological innovators,

care providers and users for the development of new services in general and, in

particular, new AAL services. We argue that ICF can be used as a conceptual

framework to systemize the information that can influence individual's performance,

not only in terms of health conditions or physiological functions, but also in terms of

contextual (both personal and environmental) factors and it can be used as

comprehensive model for a holistic approach to characterize users, theirs contexts,

activities and participation:

− The ICF body (physiological functions) and personal factors (e.g. life style,

education level, sex, race, life events or psychological characteristics) can be used

to model the final users and theirs specific needs.

− The ICF contextual (environmental and personal) factors either enhance or limit

the individual’s functioning and, clearly, must have an important role in AAL

services for older adults, considering that one of their main goal is to maintain

older adults activities and participation in society. In particular, ICF environmental

factors (e.g. physical, social or attitudinal) must be considering when modeling the

immediate or more general environment.

ICF fundamental concepts are related with functioning and performance in activities

and participation. On the other hand, the goal of AAL services for older adults is the

development of technological solutions to enhance theirs activities and participation

in all aspects of society. Therefore, it should be possible, and desired, to use ICF for:

− The specification, development and characterization of AAL services.

− The development of suitable instruments for the evaluation of the AAL services

and their impact on the daily life of older adults (i.e. activities and participation).

Potential advantages of ICF usage in several aspects of the AAL services for older

adults will be addressed in the following sections, namely: user modeling and

profiling, essential for adaptable and intelligent services; development of complex

AAL services; and AAL services evaluation.

50

3 Users Modeling and Profiling

Users modeling and profiling provides the methodology to enhance the effectiveness

and usability of services and interfaces in order to: tailor information, predict user's

future behavior, help the user to find relevant information, adapt interface features to

the user and the context in which it is used, and indicate interface and information

presentation features for their adaptation to a multi-user environment.

As a variety of users may operate with AAL services, a users’ model serve as a

description of the users of a system and a prediction of how they will behave and

perform tasks. These goals are achieved by constructing, maintaining and exploiting

user models and profiles, which are explicit representations of individual user’s

preferences.

Different models have been considered for the development of applications and

information systems for support in activities based on new paradigms that promote

the human ability to solve problems. These models differentiate the users in terms of

information processing capabilities, according to individual differences of a physical

nature, according to individual differences of a psychological nature, and also

considering environmental and cultural factors. As a result of this research a set of

meaningful international usability standards were defined.

One of this international usability standards (the ISO/IEC 24756 [9], which

defines a framework for specifying a Common Access Profile of needs and

capabilities of users, computing systems, and their environments) was used together

with ICF by the Vaalid [10] project as an attempt to characterize the user profile [10,

11], namely to qualify the abilities of the older adults that have direct impact on

successful use of ICT product and services, following the recommendations of the

ETSI EG 202 116 [12]: sensory, physical and cognitive abilities.

The abilities were classified using body functions and structures and some

concepts related with activities and participation of ICF. However, we argue that a

step forward is possible due to the fact that other individual factors, such as

anthropological characteristics or preferences can be considered using the ICF

framework. ICF, as a model that offers a balance between a purely medical and a

purely social approach, contains essential information for the profile characterization

of body functions and structures, personal factors and activities and participation:

body functions and structures allow the definition of the type of access to services, as

well as, the definition and configuration of its interfaces; personal factors allow the

characterization of personal preferences in the definition and configuration of services

and interfaces; and activities and participation allow the characterization of the

services that best fit the person’s functioning.

Detailed information associated with these components determines the type of

AAL service access, the need for assistive technology and appropriate adaptation of

its interfaces.

From the point of view of users, we can not forget that their models have to be

dynamic in order to adjust to the context in which they operate. Context can be

considered as any information that can be used to characterize the situation of an

entity. An entity is a person, place, or object that is considered relevant to the

interaction between a user and an application, including the user and application

themselves [13]. Additionally, it is also clear that not all types of contextual

51

information can be easily sensed. Some types of contextual information (e.g. the

mood of the individuals) can only be derived by intelligent combination of other

information or by human inputs [13].

The ICF model is consistent with these requirements as a person’s performance

can be characterised as the result of a complex relationship between health conditions

and personal and external factors. External factors represent the circumstances in

which the person lives, i.e. the functional performance of a person in the activities and

participation is influenced by his/her individual characteristics and participation, and

the environmental factors can be considering a facilitator or barrier to his/her

functioning.

Therefore, concerning the user model, the individuals are a combination of body

functions and structures, activities and personal and environmental factors. Personal

factors include gender, age, coping styles, social background, education, profession,

past and current experience, overall behaviour pattern, character and other factors that

influence how disability is experienced by the individual [2]. Additionally,

environmental factors can be grouped in the following classes: products and

technology; natural environment and human-made changes to environment; support

and relationships; attitudes; services, systems and policies.

However, we must be aware that the development of ICF is still work in progress

what may pose some challenges:

− Personal factors still need an in depth study to avoid the need to use concepts

outside the ICF for the complete definition of the user model.

− In the context of AAL services, it is urgent to identify habits and routines. These

are the recurring patterns of a person’s behavior, usual activities performed and

resources used. These concepts are not explicit in the ICF, but they are highly

relevant to the classification of environmental factors.

− The capture and systematization of environmental factors is one of the biggest

challenges [14]. Measure the impact of the environmental factors on human

functioning is becoming an important subject to optimize interventions and reduce

participations restrictions [14]. In recent years different instruments have been

developed for assessment of impact of environmental factors in human

functioning, reflecting the concern about the inclusion of this component of ICF in

a comprehensive assessment.

Despite the difficulties listed, we believe that the ICF can help modulate users and

theirs contexts from a holistic viewpoint. Additionally, we believe that the difficulties

mentioned must be seen as opportunities and challenges: the use of ICF beyond the

restricted field of health will bring interesting contributions to its own development

and will help the ICF to meet all the requirements identified for user model within the

AAL services.

4 Development of Complex AAL Services

The System Architecture proposed for the LUL follows the paradigm of service

orientation, which allows developing software as services that are delivered and

consumed on demand. The benefit of this approach lies in the loose coupling of the

52

software components that make up an application. Discovery mechanisms can be used

for finding and selecting the functionality that a client is looking for. Many protocols

already exist in the area of service orientation.

The architecture components are divided into three layers: the base middleware

layer contains the functionality that is needed to facilitate the operation of the

networked environment; the intelligent middleware layer contains the functionality

that is needed to facilitate the usability and acceptance of the services (it provides

users modeling and profiling, user interface management and context awareness and

notification); and the application layer allows dynamic services composition, which is

essential to allow the congregation of different services to build domain specific

applications.

Therefore, the application services have a hierarchical structure in which a

particular service is made up of components. Each one of these components could be

composed by more elementary services.

Furthermore, the interactions between the assistive devices, human services and

end users, must be under a service oriented management perspective. Assistive

devices and human services interactively work together to express potentials from

both sides providing high quality services to the people with needs [6]. Effective and

efficient solutions to meet the AAL challenges should combine the forces from both

the technological part and the societal ones. The participations of human beings could

help fully express the potential of smart devices, and maintain the social awareness of

the older adults. Although informal caregivers may help reduce the needed social

resources, and increase the social connections, they are inherently very dynamic: the

availabilities of the caregivers are continuously changing.

A scenario is a specific context where the activities and participation, features and

resources are well defined. It gives us the information about which AAL, human and

technological support services are necessary to assist older adults in social, economic,

cultural, spiritual and civic affairs.

Considering this services organization, an efficient infrastructural support for

building AAL services aggregation is needed [15]. It consists of the following

infrastructure services which act as basic service components: service registration;

semantic service descriptions; semantic match service; and service binding.

The services must be described based on a standard, commonly declarative,

service description language to enable service discovery and invocation independently

of its implementation details. An example of a suitable service description language is

the XML-based WSDL language, used to describe web services. Additionally, there

must be an ontology able to classify the different AAL services and thus facilitate

their re-use.

There are a huge number of possibilities in terms of possible classifications of

AAL services:

− Persona [5] project defines usage scenarios (these provide a basis for subsequent

specification and evaluation of services and basically define specific contexts and

how users carry out their tasks in these contexts. Since the number of available

scenarios is rather big, the end users have been asked to identify the most

interesting scenarios. This led to the selection of the following eight scenarios [5]:

peer to peer exchange; meeting other people; enhanced activity assistant; personal

53

safety; behavior detection; health status management; neighborhood assistant; help

in planning and conducting a journey using public transportation.

− In a different approach [16] AAL application are considered as composed of a set

of services that can be grouped into two categories: health-oriented services and

comfort services. Health-oriented services (e.g. health and activity monitoring)

allow the older people to access to medical and emergency services, and facilitate

collaboration among medical staff. Comfort services are services that allow the

older adults to maintain social and familiar contacts or that allow them to access

information to which they are interested or shopping assistance.

− Different services do not require the same properties of the execution environment

such as security, confidentiality or urgency. This could lead to another type of

classification [16, 17] based on three type of assistance: emergency assistance (e.g.

assistance detection, prediction and prevention); autonomy enhancement services

(e.g. drinking, eating, clearing, dressing, medication, shopping assistance or

traveling assistance); and comfort services (e.g. logistical services, services for

finding things, infotainment services transportation services or orientation

services).

− The European Ambient Assisted Living Innovation Alliance focuses on the needs

of older adults to categorize all products and research activities [11]: social

interaction (i.e. all kinds of products, services and research projects that enable

older adults to stay in touch with the world beyond their domestic environment);

health and home care (i.e. combination of supporting assistive technologies and

rather conventional health or home care solutions might be best suited to provide

the framework necessary for autonomous living conditions of older adults that can

be further divided into prevention, assistance or therapy); supply with daily goods

and chores; and safety (i.e. for fulfilling the safety, privacy and security needs of

older adults).

Considering the broad range of sub domains used to classify AAL services (which

is natural taking in consideration the maturity level of this technology) is not an easy

task to identify an appropriate semantic knowledge base to precisely describe the

advertised services. The question of how to automatically map the available/requested

services is still a big challenge in AAL.

We consider that the conceptual framework of ICF could be useful to solve critical

issues related with the services organization. Since the activities and participation, i.e.

involvement of the person in real life situation, is what justifies the use of AAL

services, we can and we should used ICF for the structuring and classification of AAL

services.

The component activities and participation is a neutral list of domains indicating

various activities and areas of life (learning and applying knowledge, general tasks

and demands, communication, mobility, self-care, domestic life, interpersonal

relationships and interactions, major life areas, community, social and civic life),

which are subdivided into three levels increasing the accuracy of the classification.

The list of areas of activities and participation covers the full range of functioning

that can be coded at the individual and social level. This component can have

different uses, considering the concepts of activities and participation. The ICF

defines four ways to use this list of domains: different groups of domains of activities

and domains of participation (not allowing overlap), partial overlap between the

54

groups of domains of activities and participation, the existence of detailed categories

of activities and broad categories of participation, with or without overlap and use the

same fields for both activities and participation with complete overlap of the fields

[2].

For the definition of an ontology to categorize the AAL services we proposed the

ICF participation domains. This implies that we have to define a border line between

activities and participation [18]: we consider the first two activities and participation

domains (learning and applying knowledge, general tasks and demands) as activities

(used to define the user profile, as they qualify the user abilities to perform activities)

and the remainder five domains (communication, mobility, self-care, domestic life,

interpersonal relationships and interactions, major life areas, community, social and

civic life) as participation because they are more related with the individual’s

performance [19].

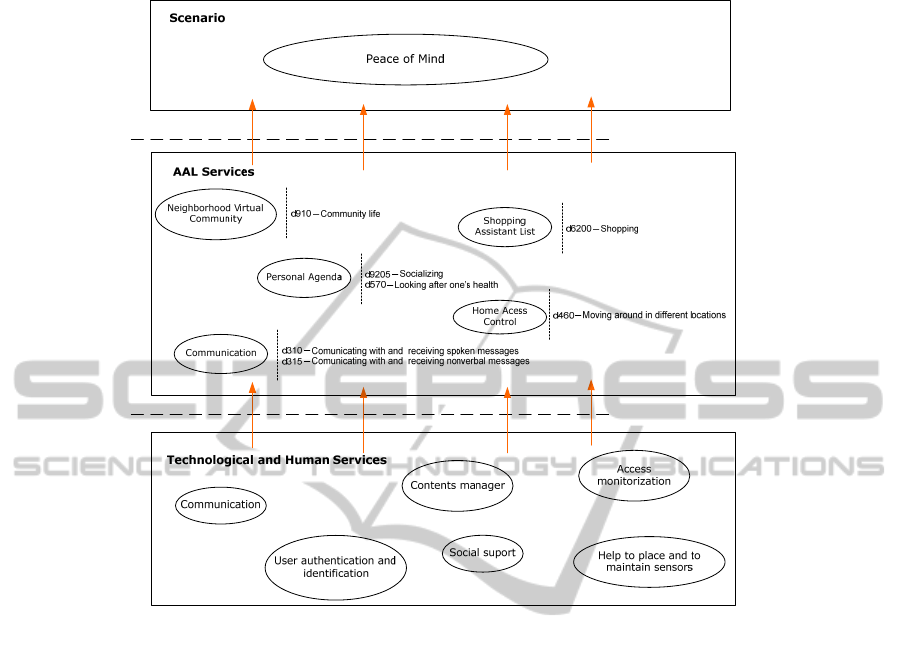

Figure 2 represents a layer organization’s services for a specific scenario (peace of

mind), using the example of a choreography of AAL services conceptualized by the

Persona [5] project in attempt to maintain peace of mind of adult child concerning the

well-being of their parents [20].

AAL services highlight the technology as a facilitator of the person’s performance

improving functioning. This means that the results associated with the development of

AAL services are strongly oriented to technology, i.e. services are conceptualized and

developed considering the potential of technology. This can cause problems when

trying to classify, according to ICF, services already developed or being developed.

However, it is clear that a structured classification of AAL services should not be

oriented to technology, but to individuals. This is a strong argument to use the ICF as

the basis for an otology for the AAL services and its components.

5 AAL Services Evaluation

The AAL services evaluation is an approach to the technology design and

development process that can be divided in two main phases: anticipation of impacts

and consequences and performance assessment.

The publication, in 1999, of the ISO 13407 standard (Human-centered Design

Processes for Interactive Systems) [21] was an international recognition that the

human factors have processes which can be managed and integrated with the project

processes. According to this ISO standard the first steps within the user centered

design process are [22]: understanding and specifying the context of use; and

collecting and analyzing users’ needs and requirements.

However, the usually approach for involving users throughout the whole R&D

process is typically followed by the development of prototypes by experts. By doing

this, decisions about the conceptual design, i.e. what kind of functions are to be

developed and what the interaction should be like, are made by experts. The

prototypes, based on those conceptual design ideas, are then evaluated by users.

Therefore, the initial design ideas are not based on the mindsets, experiences and

mental models of the users but on the experts. The user can intervene only through the

user based assessment [23].

55

Fig. 2. Peace of Mind scenario.

A central idea of the Living Lab concept is a strong involvement of the users in all

the development phases, including the conceptual design and, later, the prototypes.

Therefore, new methodologies are required to allow the generating of new design

solutions and the evaluation of design solutions derived from the first phases of user

involvement. Focused design discussions, theatre and multilevel prototyping [23].

Although the process is cyclic, it should be flexible enough to move forwards,

backwards, and crosswise between phases. Notably, practice and use are tightly

interwoven by these phases, since the output from one becomes the input for another.

In particular, the prototypes that that evolve from empirical studies may become part

of the Living Lab infrastructure for use in future studies. These prototypes together

with the evaluation results are additionally useful for future model and tool building,

and they lead to further cycling though the Living Lab [23].

The evaluation has several goals: evaluate process/ways of working changes;

measure hard data of the improvements/changes; evaluate fit between software

concepts and users real way of working; evaluate acceptance, satisfaction, motivation

and individual performance of users; evaluate usability, bugs, functionality of

software; and create ideas about improvements and new features.

For the performance assessment the technological developments have been based

on a fairly limited view and, in particular, the evaluation methodologies focus on

56

instrumental factors, such as mobility, physical and sensory deficit and ability to

perform activities of daily living and rarely on advanced activities of daily living and

social roles. There’s an imperative for changing this paradigm as the result of higher

levels of performance that health and social interventions demands. In fact, we also

need to understand how the technology influences the (re)motivation and the

(re)organization of the human performance within a particular context. Humans as

open systems can accomplish changes over time through the engagement in

meaningful activities with the propose of fulfill the sense of achievement and control

of own life. As we state before this level of functioning is a dynamic interaction

between the person and the environment where the personal causation, values,

interests, habits and routines play a very important role. To this dynamic interaction

we call it meaning.

An ecological model focused on practical aspects of everyday activities of the

person, highlighting opportunities for technology and design solutions to support

these activities is a useful framework for guiding the evaluation process. The

activities that comprise a person’s everyday life are shaped by a range of different

factors, including attributes of the person (e.g. functional ability, cognitive ability or

psychological factors) and attributes of the immediate and wider socio-cultural

contexts (e.g. formal support network, social network, physical environment or

cultural and political determinants) [11].

Assuming that AAL services intend to highlight environmental factors referring to

technology to improve participation and quality of life, such services should be

evaluated taking into account theirs impact on activities and participation of the user,

particularly on his/her quality of life, which includes the meaning and the satisfaction

of the performance.

Therefore, it is extremely important to develop new methodological approaches to

include not only the performance of the individual but also the meaning and

satisfaction with their performance.

ICF model contemplates some of the factors previously listed and also considers

that environmental factors and the individual cannot be conceptually separated. The

ICF ecological perspective are reasons strong enough to use this conceptual model to

develop methodological instruments to evaluate in a holistic perspective the impact of

AAL on older adults quality of life, including the meaning and the satisfaction of the

performance. On the other hand, it is of utmost importance to adopt the ICF as this is

a WHO classification internationally used.

6 Conclusions

In the previous sections we had presented arguments that sustain the possibility of

using ICF in different aspects of design, development and evaluation of AAL services

for older adults. ICF can be used as a universal framework to characterize users’

profiles and theirs environments, to structure a semantic characterization of AAL

services and to develop methodological instruments for the AAL services evaluation.

Therefore, we believe that ICF can be used as a conceptual framework for the

design, development and evaluation of AAL services. Within the LUL project we

57

intend to demonstrate that such a conceptual framework can overcome some of actual

difficulties related with AAL services design, development and evaluation.

One of the problems of using technology and information systems for care

provision is the communication difficulties between technology professionals and

caregivers. Different professionals with different backgrounds and needs but who

speak a common language increase the efficiency of teamwork. This leads to a better

performance when developing new services or when improving existing services. In

particular, the use of a conceptual framework from WHO, as is ICF, facilitates the

work of multidisciplinary teams.

Additionally, although it may be needed to complete ICF with additional models,

it can help to overcome a recurring problem that is the lack of data to create robust

user’s models. Properly safeguarding ethical issues, the ICF can allow almost

unlimited access to appropriate information properly encoded.

Last but not least, using the ICF to enhance the semantic interoperability

facilitates the generation of knowledge: the existence of universally accepted

conceptual models, and its terminology, concepts and coding of information allows

the aggregation and consolidation of the available information, which will be essential

for the strategic planners, technological innovators, care providers and users involved

in the development of AAL services.

Acknowledgements

This work is part of the COMPETE – Program Operacional Factores de

Competitividade and the European Union (FEDER) under QREN Living Usability

Lab for Nest Generation Networks (hrrp://www.livinglab.pt).

References

1. World Health Organisation: Active Ageing: A policy framework (2002)

2. World Health Organization: The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and

Health (ICF). Geneva, Switzerland (2001)

3. Peterson, D. B.: International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: An

Introduction for Rehabilitation Psychologists. Rehabilitation Psychology, Vol. 50, No. 2,

(2005) 105–112

4. O’Grady, M. J., Muldoon, C., Dragone, M., Tynan, R., O’Hare, G. M. P.: Towards

evolutionary ambient assisted living systems. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and

Humanized Computing, Vol 1, Number 1, Springer-Verlag (2009) 15-29

5. Ochoa, E. [et al]: PERSONA - PERceptive Spaces prOmoting iNdependent Aging -

Deliverable 2.1.1 - Report describing values, trends, user needs and guidelines for service

characteristics in the AAL Persona context (2008)

6. Hong Sun, V. F., Ning Gui, C. B.: Promises and Challenges of Ambient Assisted Living

Systems, Sixth International Conference on Information Technology: New Generations

(2009)

7. Hong Sun, V. F., Ning Gui, C. B.: Towards Longer, Better, and More Active Lives -

Building Mutual Assisted Living Community for Elder People. In the Proceedings of the

47th European FITCE Congress, FITCE, London (2008)

58

8. Kleinberger T., Becker M., Ras E., Holzinger A., Muller P.: Ambient Intelligence in

Assisted Living: Enable Elderly People to Handle Future Interfaces, Universal Access in

Human-Computer Interaction. Ambient Interaction, Part II, HCII (2007)

9. Janse, M. (ed.), Ramparany, F., Kladis, B., Rozendaal, L., Broens, T., Eertink, H.: IST

Amigo Project Deliverable D2.3 Specification of the Amigo Abstract System Architecture

(2005)

10. Mocholí, J. L., Sala, P., Navarro, A.: VAALID - Accessibility and Usability Validation

Framework for AAL Interaction Design process. D2.2 - Concept & Services ontology

description, VAALID Project (2010)

11. Broek, G. [et al]: Ambient Assisted Living Roadmap. Alliance – The European Ambient

Assisted Living Innovation Alliance (2009)

12. ETSI EG 202 116 v1.2.1 (2002-09): Human Factors (HF); Guidelines for ICT products and

services; “Design for All” (2002)

13. Ramparany, F. [et al]: IST Amigo Project. Deliverable D2.2 - State of the art analysis

including assessment of system architectures for ambient intelligence (2005)

14. Lemberg, I., Kirchberger, L., Stucki G., Cieza A.: The ICF Core Set for stroke from the

perspective of a physicians: a worldwide validation study using the Delphi technique.

European Journal of Physical and rehabilitation Medicine, 46 (2010)

15. Hong Sun, V. F., Ning Gui, C. B.: Towards Building Virtual Community for Ambient

Assisted Living. 16th Euromicro Conference on Parallel, Distributed and Network-Based

Processing, IEEE Computer Society (2008)

16. Segarra, M. T., André, F., Building a Context-Aware Ambient Assisted Living Application

Using a Self-Adaptive Distributed Model. ICAS 2009 : Fifth International Conference on

Autonomic and Autonomous Systems , Valencia (2009)

17. Avil´es-L´opez, E., Villanueva-Miranda, I., García-Macías, J. A., Palafox-Maestre, L. E.:

Taking Care of Our Elders Through Augmented Spaces. LA-WEB '09: Proceedings of the

2009 Latin American Web Congress (la-web 2009) (2009)

18. Kostanjsek, N.: Semantic Interoperability – Role and Operationalization of the International

Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), International Journal of

Integrated Care, Vol 9 (2009)

19. Jette, A., Tao W., Haley, S.: Blending activity and participation sub-domains of the ICF.

Disability and Rehabilitation (2007) 1742 – 1750

20. Rowan, J. T.: Digital Family Portraits: Support for Aging in Place, in partial fulfillment of

the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy, College of Computing, Georgia

Institute of Technology (2005)

21. DIN EN ISO 13407: Human-centred design processes for interactive systems (1999)

22. Storf, H., Becker, M., Riedl, M.: Rule-based Activity Recognition Framework: Challenges,

Technique and Learning. Pervasive Computing Technologies for Healthcare, 2009.

PervasiveHealth 2009. 3rd International Conference on In Pervasive Computing

Technologies for Healthcare, 2009. PervasiveHealth 2009. 3rd International Conference on

(2009) 1-7

23. Muller, S., Santi, M., Sixsmith,A.: Eliciting user requirements for ambient assisted living:

Results of the SOPRANO project, eChallenges Conference 2008, Stockholm (2008)

59