“Smoking Does Not Make You Happy”

Unlearning Smoking Habits Through Mobile Applications on Android OS

Răzvan Rughiniș

1

, Ștefania Matei

2

and Cosima Rughiniș

2

1

Department of Computer Science, University Politehnica of Bucharest, Bucharest, Romania

2

Department of Sociology, University of Bucharest, Bucharest, Romania

Keywords: Smoking Cessation, Android Applications, Quitting Advice, User Profile.

Abstract: We analyze in-depth five smoking cessation apps on Android OS, examining how they teach users to quit

smoking and what they learn from users. Apps advise would-be ex-smokers how to perceive the world, how

to deal with their emotions, and how to act on their bodies and environment. Still, they learn little from their

users, and even less from the scientific literature on smoking cessation. We discuss the potential for

improved customization of advice to users’ profiles and we propose a simple inventory of online scientific

resources as a starting point for developers looking to create better apps.

1 INTRODUCTION

There has been a recent increase in the use of

technologies for smoking cessation interventions.

Online programs and sites assist people who want to

quit smoking (Quit Net, Smoke Free, Make Smoking

History, Verizon Health Zone, Dit Digitale

Stopprogram etc.). SMS Services of support and

counseling (Guerrilla Interactive SMS Service,

MiQuit, Mobily Naqa, etc.) send messages tailored

to the situation of the recipient, giving advice and

encouragement.

A current advancement consists in mobile

applications designed to help people unlearn their

smoking habits, and learn a new identity with its

associated routines: the ex-smoker. They are

available on multiple platforms and mobile

operating systems (iPhone, Android, Windows 8

etc.), being released by a variety of actors, such as

independent developers, software development

companies, non-profit organizations for public

health, or public institutions.

Smoking cessation applications are, essentially,

attempts at 1) unlearning through re-interpretation of

smoking, and 2) assembling a new set of daily life

routines to support the transition to a new identity.

Their first challenge is to encourage users to reframe

smoking from a positively charged behavior

(understood in terms of prestige in group, belonging

to a group or social class, sign of capital assets,

personal and psychological relief etc.) to a damaging

action (as regards risks for self and others of

premature death, disability, low fitness and degraded

beauty; financial costs; low environmental comfort

etc.). Their second challenge is to support users

through withdrawal symptoms and craving

moments, thus avoiding a relapse.

This paper reports a case study consisting of

in-depth, qualitative analysis of five smoking

cessation applications on Android OS. We focus on

communication with users, addressing the following

questions: What do apps teach users? What do apps

learn from users? What evidence-based resources

are available for developers to improve the fit

between users’ profiles and app messages?

2 SMOKING CESSATION APPS

The market of smoking-related applications contains

both pro-smoking software (promoting tobacco

products and smoking) and anti-smoking

applications (framing tobacco consumption as

negative). Even if there are some

smoking-supporting applications (e.g. smoking

simulators) which claim to help people quit, and

could possibly be of assistance in some instances,

most of the pro-smoking application are designed as

brand advertisements, as wallpapers or widgets, and

as claims to protect the right of smoking enthusiasts

(BinDihm et al., 2012).

A comprehensive review of smoking cessation

371

Rughinis R., Matei S. and Rughinis C..

“Smoking Does Not Make You Happy” - Unlearning Smoking Habits Through Mobile Applications on Android OS.

DOI: 10.5220/0004836303710378

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2014), pages 371-378

ISBN: 978-989-758-021-5

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

applications for mobile phones show that most

quitting applications do not adhere to key medical

guidelines: “Few, if any, apps recommended or

linked the user to proven treatments such as

pharmacotherapy, counseling, and/or a quit line”

(Abroms et al., 2011). The applications propose

what we can term a “lone rider” model of the user: a

heroic vision of quitting unassisted by medicine or

professionals. A similar conclusion is advanced by a

review of alcohol quitting apps (Cohn et al., 2011).

We start from this observation and we examine

in-depth advice and tips offered by five smoking

cessation apps which are, in our evaluation, typical

for apps that are based on a combination of

quantification, gamification, community, and textual

communication, the most frequent type on the

Google Play market. We then discuss our findings

by pointing out missed opportunities for

personalization of advice, and missed opportunities

for learning from the available online scientific

discussion on smoking cessation.

3 DATA AND METHOD

For our case-study we selected for in-depth analysis

five smoking cessation applications on Android: [1]

Stop Smoking (developed by Konrad Müller, last

updated: November 2011), [2] Quit Smoking Coach

(developed by Studios BrainLag, last updated:

August 2013), [3] Kwit - Quit Smoking is a Game

(developed by Geoffrey Kretz and Nicolas Lett, last

updated: August 2013), [4] Stop Smoking Assistant

(“As If” Licence, last updated: September 2012) and

[5] Exsmokers iCoach (developed by Saatchi &

Saatchi Brussels for the European Commission,

April 2013).

Through this selection we cover application

variability in terms of design features (Abroms et

al., 2011): the selected apps illustrate quantified

communication, textual advice and tips, games and

gamification, and community support. We have also

selected for analysis apps among those that include

richer textual messages for users, so that we could

examine their patterns of communication. We have

identified and analyzed a total of 498 pieces of

advice and panic tips provided by these five apps.

We excluded tools that are based on hypnosis or

subliminal messages because depend on strong

assumptions, addressing a specific niche of users.

Based on our previous exploratory survey of

anti-smoking apps, we consider that the five selected

solutions are broadly representative of the available

smoking cessation apps found on Google Play,

integrating the most frequent options available in

this type of work. Our case study serves to illustrate

significant patterns and to open a discussion on the

potential for improving advice for people who

attempt to quit.

4 RESULTS

Smoking cessation applications often propose one or

several frames for the communication with their

users. Some of the most common frames are:

1) Coach or assistant: the application guides the

user through the difficult venture of quitting;

2) Game: the application offers a gameful

environment in which smoking cessation is a

quest, or in which ex-smokers can enjoy games

as rewards for their abstinence;

3) Community: the application facilitates an online

support community of ex-smokers.

Communication between the application and

users mostly occurs in the coach/assistant frame. It is

bi-directional, although the two flows are, as a rule,

clearly separated. Users are required to provide for

the application a profile of their smoking habits,

which are their most important identifier: this

information typically includes the number of

cigarettes smoked per day, time spent while smoking

a cigarette, the number of cigarettes per pack, and

the cost of a pack. Additional information on

smoking inception and type of cigarettes may also

be solicited. Users are also expected to honestly

communicate each cigarette smoked; if the user has

identified herself / himself as an ex-smoker,

reporting a relapse usually resets all indicators and

progress measures to zero. Last but not least, users

are expected to ask for tips in case of cravings and

feelings of panic. In turn, the application provides

two different types of information:

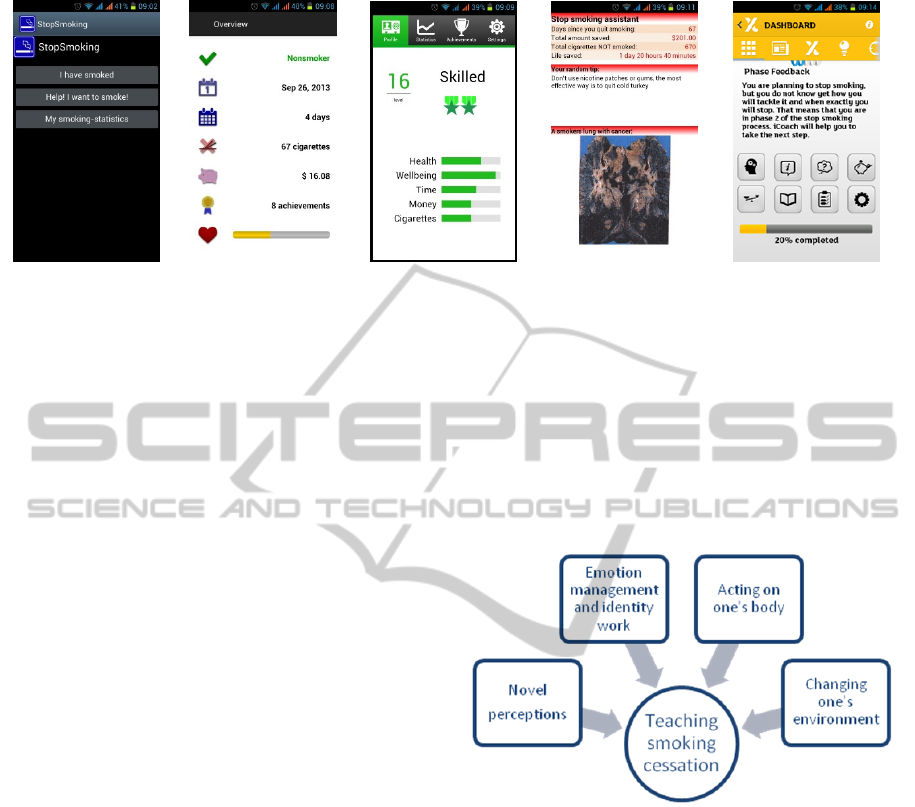

1) A quantitative representation of the user’s

transformation and foreseeable future, with a

focus on health benefits and financial savings

(see app front pages illustrated in Figure 1); this

representation usually include a combination of

numbers and percentages, progress bars and

other charts;

2) Advice, consisting of motivational quotes or

panic tips; some applications also include

motivational graphic images illustrating

smoking-induced damage.

Therefore, apps learn from users, and teach users

how to deal with smoking cessation. As we argue

below, smoking cessation apps do a minimal work in

learning from users, as user information is only

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

372

[1] Stop Smoking [2] Quit Smoking Coach

[3] Kwit – Quit

Smoking is a Game

[4] Stop Smoking

Assistant

[5] Exsmokers iCoach

Figure 1: The front page of smoking cessation applications.

employed in the quantitative engines that generate

numerical indicators and predictions, with little

relevance for advice and tips.

4.1 Teaching Users

Apps are in charge of assisting users in a transition

from a life structured by smoking routines, to a

smoking-free life, through a period of withdrawal

symptoms and craving. To this purpose, applications

teach users to perceive the world differently, to

manage their emotions and see themselves in a new

way, and to engage in specific behaviors to

minimize risks of relapse. We examine below in

detail how apps teach users to deal with the

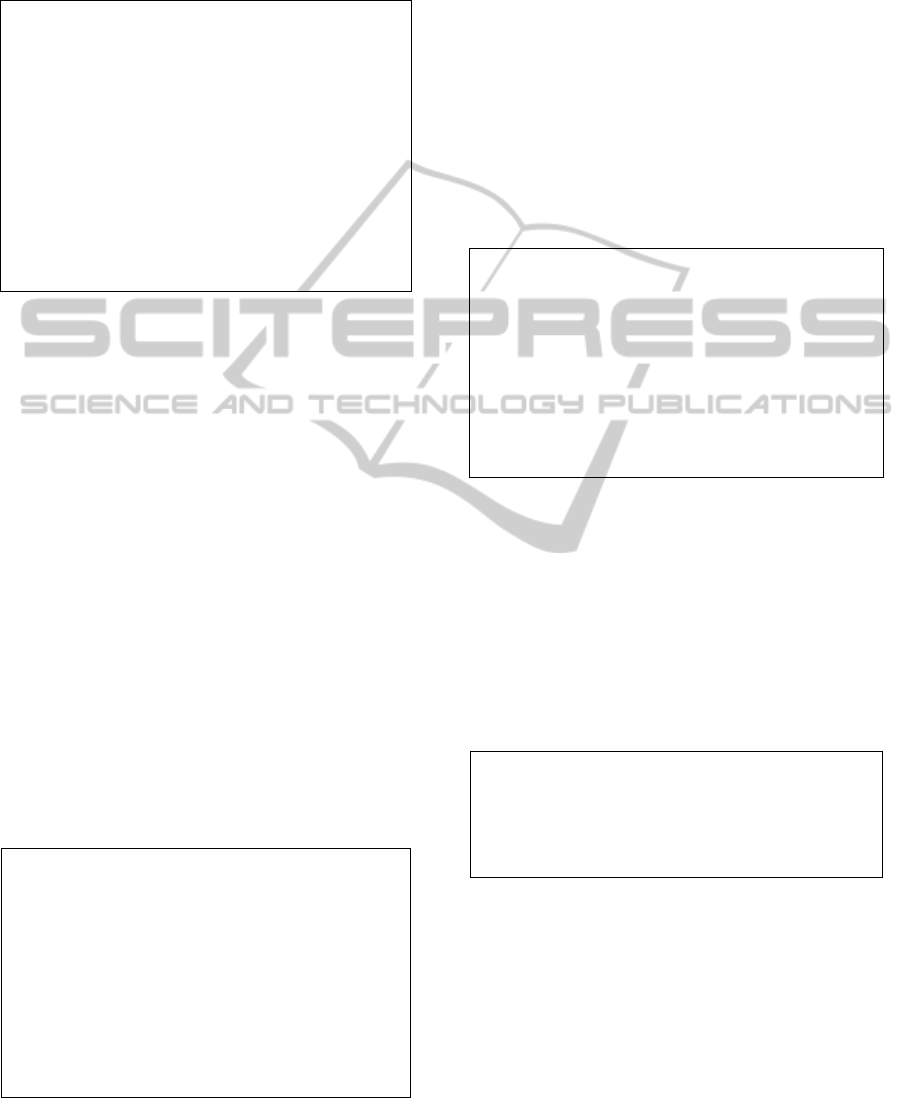

experience of smoking cessation on four domains:

perceptions, emotions, bodily actions, and

environmental contexts (Figure 2).

As regards perceptions, there are four teaching

areas:

1) Perceiving the future: users are presented with

information about the distant future, especially

concerning their improved health status in 10 to

20 years; users are also faced with descriptions

of the closer future – a period free of cravings

and dependency, in which the benefits of

cessation are already visible and the costs have

become memories;

2) Perceiving one’s body in time: users are

prompted to consider the gradual transformations

of their bodies, while and after giving up

smoking;

3) Changing one’s perception of cigarettes as

objects of consumption.

4) Managing one’s perception of time, through time

work (Flaherty 2003);

As regards one’s emotions and identity, apps

purport to teach users about:

1) Managing one’s emotions, in a process of

emotion work (Hochschild 1979);

2) Changing one’s definition of oneself, in a

process of identity work (Schwalbe &

Mason-Schrock 1996).

Last but not least, apps also teach users to act on

their body, shaping physical needs and sensations,

and to be aware of one’s context and act on the

material and social environment.

Figure 2: Four domains of app advice for users.

4.1.1 Perceiving the Future

The quantitative representation of users’ progress is

the most important tool for visualizing the future.

Applications take over the role of a ‘magnifying

glass’, compensating for users’ myopia as regards

future risks and benefits. The future is materialized

as: the right end of a progress bar that fills gradually,

the prospect of full recovery from smoking damage

after 15 years of non-smoking, life-years gained

through non-smoking, and through various metrics

that display improved health and life expectancy.

Applications attempt to direct users to mind the

future not only through indicators, progress bars and

charts, but also through advice and panic tips (see

Figure 3; in all Figures presenting application

advice, the source of each quote is indicated in

"SmokingDoesNotMakeYouHappy"-UnlearningSmokingHabitsThroughMobileApplicationsonAndroidOS

373

square brackets, referring the application list from

the Data and Methods section). Users are put in the

situation to foresee their future health, but also their

change of mind and emotions.

Ten years after quitting your lung cancer risk will be

reduced to 50%. [A1]

In a few months, you will no longer think about

smoking. [A1]

When you haven’t smoked for a month or more you

will realize how stupid it was to spend all that money

on an addiction that was literally killing you! NEVER

AGAIN! [A4]

Quitting keeps you young! Research has proven that

smoking affects your body's cells, accelerating the

aging process.[A5]

The most difficult thing is to resist the first few

weeks, and mainly the first days. It will be easier as

time passes. [A3]

Figure 3: Teaching users: Perceiving the future.

4.1.2 Perceiving One’s Body in Time

Users are instructed to attend to gradual

improvements in their bodily well-being. This

learning project is one of the most difficult to

sustain, since it is subject to the possibility of direct

disconfirmation: smokers are expected to experience

all these improvements but, occasionally, it is

possible that they do not occur as planned.

Applications address this vulnerability, at least in

part, by not soliciting users to actually observe their

experiences: instead, the transformations are

formulated as known-facts, in the present tense or

future tense. These statements actually instruct the

user how to perceive her bodily functions. Health

improvements cannot be possibly observed on an

hourly basis – but they can be reflected upon as

such. It is also likely that respiration will not

improve perceivably in three days – but the

improvement that occurs is rendered visible through

the application.

Without smoking your health will increase from hour

to hour. [A1]

Three days after last cigarette the function of your

respiratory system is improving. [A1]

48 hours after the last cigarette smells and tastes are

being experienced more intensively. [A1]

Your teeth, your breath and your skin thank you.

Smoking leads to tooth loss, gives you bad breath

and a shallow complexion. [A3]

Think of your sex life! Smoking influences blood

circulation in the genitals, which can lead to

diminished ability in bed. [A5]

Figure 4: Teaching users: Perceiving one’s body.

While in the previous section we have examined

the applications ‘telescopic’ function for seeing the

future, that compensates for users’ time discounting

(Frederick et al. 2003), this area of advice positions

the application as a ‘microscope’, useful for

revealing users the minute, gradual,

real-but-unobservable changes in their bodies.

4.1.3 Changing Perceptions of Cigarettes

Applications also attempt to change users’

perception of cigarettes themselves as objects of

consumption. These messages are comparatively

rare: we have identified only 4 out of a total of 498

(see Figure 5).

Each cigarette shortens your life expectancy for 8-10

minutes. [A1]

Light cigarettes will not help… you will simply

smoke more of them or inhale deeper to get same

effect. Just don’t smoke. [A4]

Think of the many poisons in a cigarette: ammonia,

acetone, methanol,... still want to light up? [A5]

By panicking, you give the cigarette too much power.

Some perspective: a cigarette is nothing more than

some tobacco wrapped in paper. Nothing special.

[A5]

Figure 5: Teaching users: Perceiving cigarettes.

4.1.4 Changing Perception of Time

Time work refers to people’s actions undertaken to

transform the experience of time – that is, either to

speed it up or slow it down, or modify its rhythms

and flavors (Flaherty 2003). This is particularly

relevant for ex-smokers: applications provide

instructions for managing the objectively short but

subjectively long periods of craving (see Figure 6).

Delay: Craving usually passes quickly. Tell yourself

that you must wait “just 10 more minutes” until

craving passes. [A2]

The urge to smoke is due to the lack of nicotine, it

doesn’t last more than 5 minutes. Stand firm and

drink a big glass of water. [A3]

Figure 6: Teaching users: Time work.

Users are made aware of the temporary and brief

nature of cravings, and they are taught a variety of

actions that could serve to distract attention and

make time pass more quickly.

4.1.5 Emotion Work

Hochschild (1979) introduces the concept of

‘emotion work’ to refer to the actions through which

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

374

people conform to emotion rules, adjusting their

emotional displays and experiences in accordance

with the situation. Emotion work is a central element

of advice for smoking cessation applications, as

recent ex-smokers are expected to confront many

negative feelings.

The applications use several generic resources: a

focus on the pride of transformation, positive

emotions induced through gratifications, acceptance

of negative emotions, and plain reframing: “smoking

does not make you happy. It is simply very addictive

[A1]” (see Figure 7).

Actually, smoking is no longer fun for you? [A1]

Smoking does not make you happy. It is simply very

addictive [A1]

You will be very proud of yourself as an ex-smoker

[A1]

Buy something nice: It’s ok, you are saving a lot of

money though not smoking. Reward yourself. [A2]

Think positive thoughts about how awesome it is that

you are quitting smoking and getting healthy. Be

patient with yourself. [A3]

Take 5 minutes and mentally review your list of reason

to quit smoking. Remember how you felt when you

decided to quit. [A3]

Be prepared for a rollercoaster ride of emotions:

denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance, and

complacency. These are normal emotions for your

body when going through withdrawal. [A4]

Figure 7: Teaching users: Emotion work.

People adjust quickly to feeling fitter. Remember that

it's the fact you've quit that makes you feel so good.

[A5]

Speak to yourself in a positive manner: 'I'm working

on a healthy future', 'I'm doing well'... convince

yourself to keep going. [A5]

You might sometimes glorify the past and miss

smoking. This is nothing more than the 'rose-tinted

spectacles’ phenomenon! [A5]

The more you fight against difficult moments, the

more intense they feel. The key to success lies in

accepting and letting go. [A5]

Use your wildest imagination to exaggerate this

moment, just like in a dramatic film. You'll soon see

how ridiculous it is. [A5]

Humour helps to put moments of panic into

perspective. Laughter reduces stress. Even

anticipating a laughing fit ('this'll be fun!') can help!

[A5]

Everything has its time, even your panic. Instead of

being afraid of it: observe this feeling, it is something

you can bear.[A5]

Figure 8: Teaching users: Emotion work in finer detail.

Exsmokers iCoach (App 5) differs from the other

applications by engaging emotion work in more

depth: smokers are oriented to observe processes of

emotional adjustment to change, to avoid nostalgia,

to use humor and ‘wild imagination’ to combat

cravings, to observe panic and to actually talk to

themselves - in a clearly observable instance of

emotion work (see Figure 8).

4.1.6 Identity Work

Schwalbe & Mason-Schrock (1996) use the concept

of ‘identity work’ to refer to the discursive actions

through which people create identities for

themselves and for others, by using, modifying, and

creating categories and subcategories adequate to

their interactional interests. We can observe how

applications propose the identity category of

‘ex-smoker’, positioning it in conflict with the

tobacco industry and in contrast with the category of

‘smokers’ (see Figure 9).

Don’t let the government and the tobacco industry

earn even one more cent from you. [A1]

On average, smokers die 7-8 years earlier than

non-smokers. [A1]

Don't be afraid to look ridiculous. The world looks

up to the brave ones, even if they don't succeed at

first.[A5]

This is not buckling under pressure from others! You

stop smoking for yourself. To feel good and to feel

healthy. [A5]

You are no-smoker now, and you are strong enough

to resist the craving to smoke. Believe in yourself.

[A3]

Smokers are comparable to alcoholics and heroin

addicts. You fool yourself, and tell yourself it’s not

that bad an addiction to have. Treat yourself like an

alcoholic and never touch another cigarette again!

[A4]

Don't you choose what you do? As long as you keep

smoking, you're at the mercy of a cigarette. Do you

smoke or are you being smoked? [A5]

Figure 9: Teaching users: Identity work.

The main identity feature of the ex-smoker

identity is its autonomy, in contrast with smokers’

addiction. This autonomy is also marked as freedom

from others, from the government, and from tobacco

companies.

An interesting aspect of identity work in

smoking cessation applications consists in the

proposed differentiation between users and their

‘brains’ (see Figure 10). Following a cognitivist

vocabulary (Coulter 1979), applications instruct

users to consider their brains as agents: thus, it is

brains who learn, feel pleasure, or think – while

"SmokingDoesNotMakeYouHappy"-UnlearningSmokingHabitsThroughMobileApplicationsonAndroidOS

375

users are positioned as observers of these neuronal

processes, gaining freedom from their biological

determination.

Throw away all cigarettes you have. You need to

resist just a little longer. You are still getting used to

non-smoking in certain situations. Your brain is still

learning. [A2]

You can train yourself to enjoy other things than

smoking. Your brain's pleasure centres are currently

overly focused on cigarettes as a source of pleasure.

[A5]

After quitting, your brain will be well supplied with

blood, you will be better at thinking. [A1]

Figure 10: Teaching users: ‘Observe your brain’.

4.1.7 Body Work

Applications commonly advise ex-smokers to

engage in physical exercise and other forms of

physical activity (sauna, brushing one’s teeth,

drinking water, raising sugar levels etc. – see Figure

11).

Instead of smoking, go swimming. [A1]

Get physical: Physical activity reduces craving. Put

on shoes and go running. Do push-ups, knee-bends,

and so on. [A2]

When blood sugar levels drop, cravings can seem

more powerful while you feel less able to manage

them. Eat fruit (apple, grapes, kiwi) or a yogurt to

feel better. [A3]

Craving a cigarette? Brush your teeth and enjoy that

fresh taste. [A3]

Drink cranberry juice, it helps remove the poison

nicotine from your system. [A4]

Self-control issues could be down to a lack of sugar.

To keep yourself in line: eat some fruit or bread. [A5]

Figure 11: Teaching users: Body work.

The autonomy-based identity work presented in

section 4.1.6 explains applications’ reluctance to

direct users towards medical or pharmacological

help. Among the 498 advice messages that we have

analyzed, only one instructs users to “Seek help

from a doctor or pharmacist” [A2]. The second

mention of a doctor serves to enhance autonomy at

the expense of medical authority: “Why are you

considering quitting? The motivation to quit must

come from you. Don't do it to please your family or

your doctor” [A5].

Unlike other solutions, Exsmokers iCoach (App

5) includes a dedicated page with a detailed

presentation of pharmacological alternatives

available for ex-smokers, recommending users to

seek medical help.

4.1.8 Environmental Work

Last but not least, there is substantial advice related

to observing and intervening on one’s material and

social environment. The concept of ‘smoking clues’

refers to situational elements that elicit the need to

smoke. Applications provide some advice to

diminish these contextual clues, and to enhance

material and relational support for the difficult

transition (see Figure 12).

Throw away everything that is associated with

smoking, ashtrays, lighters, cigarettes, … [A1]

Distract yourself: Call somebody. Write a text

message. Go for a walk. Play a game on your phone.

Make a coffee. [A2]

Escape the situation: Go to some other place. Talk to

some other people. Avoid trigger situations [A2]

Keep pictures of loved ones on you. When you will

feel cravings, look at those pictures and think about

all the love you have for these people. [A3]

Where are you right now? This location is probably

strongly associated with smoking. Get away for a bit.

Try to stop smoking in this spot. [A5]

Don't get caught out by events that push you back to

your old habits. You're doing the right thing: keep it

that way! [A5]

Figure 12: Teaching users: Environmental work.

5 LEARNING FROM USERS

As we have discussed above, apps (and app

developers) gather little information from users,

mostly focused on their quantified history and

patterns of smoking. This information serves to

customize the quantified messages that position

users on a short- and long-term trajectory from

heavy health risks to non-smokers’ health risks.

Textual advice is not personalized – with the

exception of App 5 that adjusts messages according

to users’ stage in the process of smoking cessation.

There are two main possible ways of

personalizing communication with the user. On the

one hand, apps could generate a more detailed user

profile, estimating the motives of smoking, the

degree of addiction, and the severity of withdrawal

symptoms, which is associated with the probability

of relapse. These profiles can be constructed using

available online scales, as we discuss in the next

section. On the other hand, apps could ask users to

rate the received advice and tips, and infer a profile

from users’ expressed preferences – that may vary as

regards the domain of action (perceptions, emotions,

body, or environment), tone (more or less focus on

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

376

fear from smoking damage, more or less acceptance

of guilt, more or less humour) as well as a

preference for shorter or longer messages, or

reflective versus action-oriented tips.

6 LEARNING FROM ONLINE

SCIENTIFIC LITERATURE

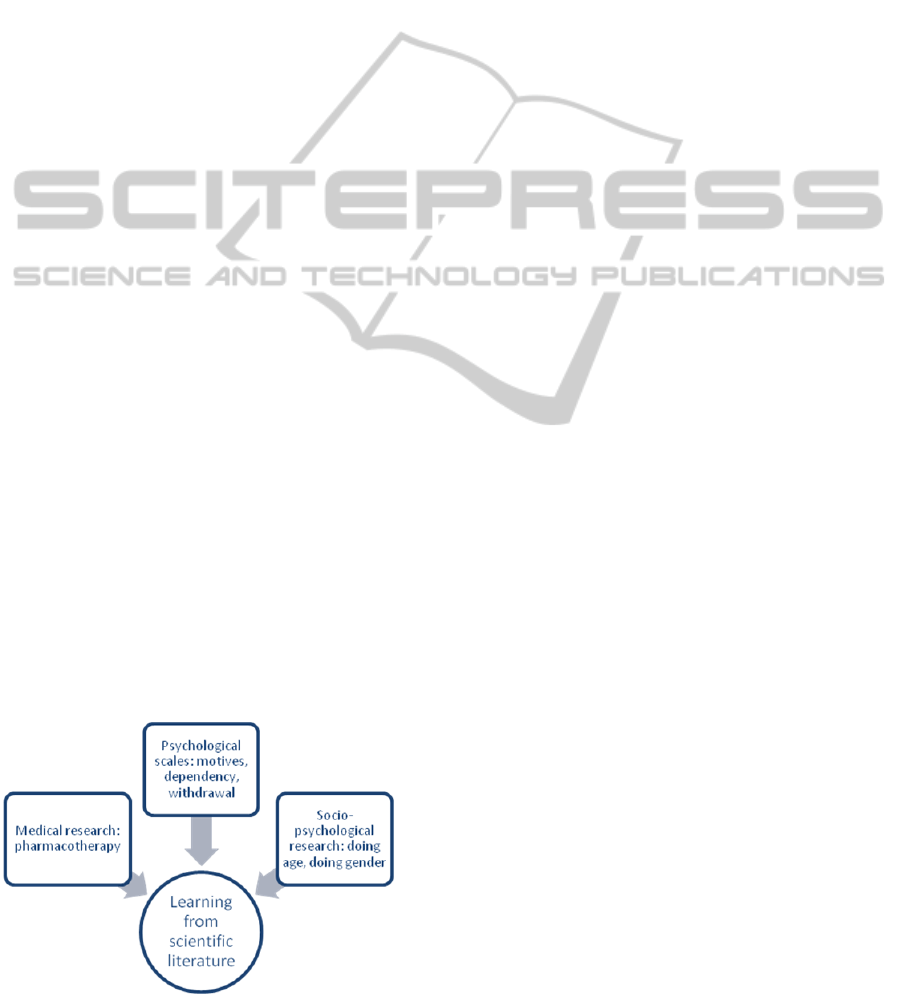

Our analysis supports Abroms’ et al. (2011)

conclusion that smoking cessation apps do not

adhere to medical advice: they largely rely on a

common-sense ‘cold-turkey’ model and ignore the

helpful potential of counselling and

pharmacotherapy.

There is no shortage of scientific literature on

smoking and smoking cessation freely available

online. We propose a brief inventory as a guide for

developers in reviewing the literature.

Medical research is useful for understanding the

benefits and often the necessity for nicotine

replacement therapy (Benowitz 2008).

Psychological scales are relevant for better

comprehending the variety in smoking motives,

addiction, and withdrawal symptoms and intensity:

- Scales for assessing the intensity of addiction to

nicotine: the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine

Dependence (Fagerstorm et al., 1990); The

Cigarette Dependence Scale (Etter et al., 2003);

the Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale

(Shiffman et al., 2004); the Autonomy over

Tobacco Scale (Wellman et al., 2011);

- Scales for identifying users’ motives for

smoking: The Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking

Dependence Motives: WISDM 68 (Piper et al.,

2004) and WISDM 37 (Smith et al., 2010);

- Scales for assessing users’ withdrawal: the

Wisconsin Smoking Withdrawal Scale (Welsch

et al., 1999) and the Wisconsin Predicting

Patients’ Relapse Scale (Bolt et al., 2009).

Figure 13: Domains of scientific literature on smoking.

Apps advice does not actually address the functions

of smoking in users’ daily life, as detailed in the

WIDSM scale, for example. Most tips only refer to

cravings and loss of control; some refer to

environmental cues. Taking into account the other

motives for smoking may improve the subjective

relevance of advice.

While social cues feature as a distinctive motive

for smoking in psychological scales, the implicit

social process remains rather abstract. The concrete

social uses of smoking can be better understood

through socio-psychological research that points to

the identity work that smokers achieve through

smoking. Smoking is often important for expressing

one’s gender, class, and age identities (Rugkasa et

al. 2003; Barbeau et al. 2004; Amos & Bostock

2007) – a feature easily visible in smoking adds that

have for long framed the cigarette as a symbol of

masculinity and, respectively, femininity, in

conjunction with age and social class. Apps could

address the usefulness of smoking for gender and

age identity work through their advice,

acknowledging this function and proposing

replacements.

7 CONCLUSIONS

Apps teach users new ways of perceiving the world

and their bodies, of dealing with their emotions, of

acting on their body and environment.

Still, apps learn surprisingly little from users:

user profiles are summarily sketched to serve the

quantification modules of health predictions, and

there is no customization of advice and tips.

There is also little reliance on scientific

literature. Mobile apps propose a user identity based

on the core value of autonomy and the lay theory of

‘cold-turkey’ quitting. Users are represented as ‘lone

riders’, in a difficult quest, assisted only by their

coach – the application, and other peers (family,

friends, networks). This identity project makes

applications reject medical and pharmacological

advice, in contrast with evidence-based

recommendations for smoking cessation. Beyond

medical literature, we propose that psychological

research concerning scales of smoking addiction,

motives, and withdrawal, and socio-psychological

research on identity work through smoking offer

valuable and easily accessible resources for app

developers in order to create rich user profiles,

develop their repertoires of advice, and personalize

tips to users’ preferences and needs.

"SmokingDoesNotMakeYouHappy"-UnlearningSmokingHabitsThroughMobileApplicationsonAndroidOS

377

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This article has been supported by the project

“Sociological imagination and disciplinary

orientation in applied social research”, with the

ANCS/UEFISCDI grant

PN-II-RU-TE-2011-3-0143.

REFERENCES

Abroms, L. et al. 2011. iPhone Apps for Smoking

Cessation: A Content Analysis. American Journal of

Preventive Medicine, 40(3), 279–285.

Amos, A. & Bostock, Y. 2007. Young people, smoking

and gender A qualitative exploration. Health

education research, 22(6), 770–81. http://

her.oxfordjournals.org/content/22/6/770.long.

Barbeau, E. M., Leavy Sperounis, A. & Balbach, E. D.

2004. Smoking, social class, and gender: what can public

health learn from the tobacco industry about disparities in

smoking? Tobacco Control, 13(2), 115–120.

http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/13/2/115.full.

Benowitz, N. L. 2008. Neurobiology of Nicotine

Addiction: Implications for Smoking Cessation

Treatment. The American Journal of Medicine, 121,

3–10.

BinDihm, N., Freeman, B. & Trevana, L. 2012. Pro

smoking apps for smartphones: the latest vehicle for

the tobacco industry? Tobacco Control, 1–7.

Bolt, D.M. et al. 2009. The Wisconsin Predicting Patients’

Relapse questionnaire. Nicotine & Tobacco Research,

11(5), 481–492. http://www.ctri.wisc.edu/Researchers/

WI PREPARE09.pdf.

Cohn, A. et al. 2011. Promoting Behavior Change from

Alcohol Use through Mobile Technology: The Future

of Ecological Momentary Assessment. Alcoholism:

Clinical and Experimental Research, 35(12), 2209–

2215.

Coulter, J. 1979. The Brain as Agent. Human Studies, 2,

335–348.

Etter, J. F., Le Houezec, J. & Perneger, T. 2003. A Self

Administered Questionnaire to Measure Dependence

on Cigarettes: The Cigarette Dependence Scale.

Neuropsychopharmacology, 28, 359–370. http://

knowledgetranslation.ca/sysrev/articles/project21/Ref

ID3219 20090722180832.pdf.

Fagerstorm, K. O., Heatherton, T. F. & Kozlowski, L. T.

1990. Nicotine Addiction and Its Assessment. Ear,

Nose and Throat Journal, 69(11), 763–765.

http://www.dartmouth.edu/~thlab/pubs/90_Fagerstrom

_etal_ENTJ.pdf.

Flaherty, M. G. 2003. Time Work: Customizing Temporal

Experience. Social Psychology Quarterly, 66(1), 17–

33.

Frederick, S., Loewenstein, G. & O’Donoghue, T. 2003.

Time Discounting and Time Preference: A Critical

Review. In G. Loewenstein, D. Read, & R.

Baumeister, eds. Time and Decision: Economic and

Psychological Perspectives on Intertemporal Choice.

Russell Sage Foundation, 13–86.

Hochschild, A. R. 1979. Emotion Work, Feeling Rules,

and Social Structure. American Journal of Sociology,

85(3), 551–575.

Piper, M. E. et al., 2004. A multiple motives approach to

tobacco dependence: The Wisconsin Inventory of

Smoking Dependence Motives (WISDM 68). Journal

of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(2), 139–

154. http://www.ctri.wisc.edu/Researchers/

AcceptedWISDMManuscript.pdf.

Rugkasa, J. et al. 2003. Hard boys, attractive girls:

expressions of gender in young people’s conversations

on smoking in Northern Ireland. Health Promotion

International, 18(4), 307–314.

Schwalbe, M. L. & Mason Schrock, D., 1996. Identity

work as group process. Advances in Group Processes,

13, 113–147.

Shiffman, S., Waters, A.J. & Hickcox, M. 2004. The

Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale: A

multidimensional measure of nicotine dependence.

Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 6(2), 327–348.

http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Saul_Shiffman2/.

Smith, S. S. et al. 2010. Development of the Brief

Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence

Motives. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 12(5), 489–

499. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/

PMC2861888/pdf/ntq032.pdf.

Wellman, R. J. et al. 2011. Psychometric Properties of the

Autonomy over Tobacco Scale in German. European

Addiction Research, 18, 76–82. https://

umassmed.edu/uploadedFiles/fmch/Research/Publicati

ons/Psychometric properties article.pdf.

Welsch, S. K. et al. 1999. Development and Validation of

the Wisconsin Smoking Withdrawal Scale.

Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 7(4),

354–361. http://www.ctri.wisc.edu/Researchers/

WSWS.pdf.

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

378