Designing an Effective Social Media Platform for Health Care

with Synchronous Video Communication

Young Park

1

, Mohan Tanniru

1

and Jiban Khuntia

2

1

College of Business Administration, Savannah State University, Savannah, GA 31404, U.S.A.

2

School of Business Administration, Oakland University, Rochester, MI 48309, U.S.A.

3

Business School, University of Colorado Denver, Denver, CO 80238, U.S.A.

Keywords: Social Network, Synchronous Video Communication, Healthcare, Multi-tier Application Architecture.

Abstract: Online social networks are evolving as platforms for health communication among the public, patients, and

health professionals. Existing health social network based portals do not provide synchronous -video-based

communication features; and are restricted to only text and picture based content sharing. Arguably,

healthcare focused online social networks need video based communication for active knowledge sharing

between providers and patients, peer-patients, or sharing disease related information through visual media.

This study provides a technological framework and design architecture to develop a customizable online

healthcare social media network that can incorporate synchronous video communication capability. The

design principles and layers that support different types of functionality are described. An evaluation in the

context of Rheumatology and back pain patients is underway and will not be discussed in this paper due to

page constraints.

1 INTRODUCTION

Use of online social health networks is increasing

with the understanding that online communication

and support is highly effective to manage own health

(Giustini 2006; Heidelberger 2011; Thackeray et al.

2008). In addition, online social media platforms

are providing conduits for providers to increase

clinical competence of healthcare practitioners

through constant monitoring and support

mechanisms (Green and Hope 2010; McNab 2009).

The emerging use of social media in healthcare is

centered around interactions between individuals

and health organizations, and the nature and speed at

which these interactions support communication of

health related issues (Frost and Massagli 2008;

Hawn 2009; Landro 2006). In the United States,

61% of adults search online and 39% use social

media such as Facebook for health information (Fox

and Jones 2009). Globally, the adoption rate is

similar, such as 45% of Norwegian and Swedish

hospitals are using LinkedIn, and 22% of Norwegian

hospitals use Facebook for health communication,

and Facebook is emerging as the fourth popular

source of health information in UK (Heidelberger

2011). Moreover, with the focus on decreasing the

growing healthcare costs, social media is posited to

provide a cost-effective means to support patient-

doctor interactions (Hillestad et al. 2005).

Irrespective of the increased use of social media

sites in healthcare, design issues pose a significant

challenge for effective use of these media in

diagnosis, treatment, and intervention. Specifically,

the lack of synchronicity among these sites is a

major issue for both patients and providers. For

example, a patient cannot get an expert opinion, as

opposed to unreliable opinions from friends and

family, to his current breathing issues (say, due to

asthma) just by logging into a social network site

given that most of these are designed to access

archived information. Several existing healthcare

social networking portals use communication

methods such as emails, published articles or

discussion forums (see Table 1 for a detailed list and

features of social networking portals). They lack

scalability to support synchronous communication

for online consultation, which would greatly

contribute to improving communication between

health professionals and patients. To our knowledge,

no social network portal has the capability to make a

doctor available to a patient through a video

communication instantly. Furthermore, as healthcare

434

Park Y., Tanniru M. and Khuntia J..

Designing an Effective Social Media Platform for Health Care with Synchronous Video Communication.

DOI: 10.5220/0004905204340441

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Health Informatics (HEALTHINF-2014), pages 434-441

ISBN: 978-989-758-010-9

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

Table 1: Sample Healthcare Web Portals and Social Media Sites.

Website Name & URL Focus

Communication

Methods

Content Categories

Steady Health

www.steadyhealth.com

How to live healthily under

different categories. Covers

disease treatments and diets.

Information Center;

Articles; Discussions;

Videos; Slideshows;

Medical Answers;

Applications

Categorized by: Well Beings

(purposes); Health Conditions

(disease types); Family Heath

( Sex and Age); Therapies &

Treatments; Emotional & Mental

Health

Wellness

www.wellness.com

How to live healthy under

different categories. Covers

disease treatments and diets. Also,

information about fitness and

beauty.

Blogs; Forum;

Articles

Popular Topics; Facilities; Fitness

& Beauty; Dental Care; Stores;

Insurances; Doctors; Mental

Health; Counseling; Provider

Program; Community

Everyday Health

www.everydayhealth.com

Diseases, drug information, living

healthily (food & diet).

Articles; Videos;

Twitters; Facebook;

Blogs; Applications

Conditions (diseases); Drugs;

Health Living; Food & Recipes;

Advices & Support

Find a doc

www.findadoc.com

Devised a unique proprietary

rating system that helps patients

choose from among the 720,000

practicing physicians in the U.S.

NA

Contact Information Search by

Categories

My doc hub

www.mydochub.com

Offers doctors' information,

hospital information and diseases

information.

Articles; Discussions;

Blogs; Applications

Doctors; Reviews; Dentists; Blog;

Answers; Chiropractors;

Hospitals; Vets; Health; News;

Health A-Z; Articles

Spark People

www.sparkpeople.com

Focused on living healthily

depending on food and exercises.

Information Center;

Articles; Discussions;

Videos; Boards;

Applications

Eat Better; Feel Better; Look

Better

Physician Data Query

www.cancer.gov/cancerto

pics/pdq

PDQ (Physician Data Query) is

NCI's comprehensive cancer

database.

Search Engine NA

Health grades

www.healthgrades.com

Doctors' information, hospital

information and dentists'

information.

NA

Find Doctors; Find Dentists; Find

Hospitals

Vitals www.vitals.com

Find and review doctors, make an

appointment and prepare for the

doctor visit.

NA

Patient Education; Write a

Review

RatMD.com

www.ratemds.com

Find and review doctors and

hospital information.

FAQ; Forums;

Tweeters

Find a Doctor; Find a Doctor;

Browse Doctors; Hospitals; Top

Local Doctors; FAQ; Forums

Drscore.com

www.drscore.com

Find doctors information. Email

Find a doctor; Score your doctor;

For Patients

Doctortree.org

www.doctortree.org

Find doctors information. NA Search Engine by Categories

Suggest a doctor

www.suggestadoctor.com

It helps to find doctors

information.

Customers'

Evaluations

Search Engine by Categories

Healthcare.com

www.healthcare.com

Information about health

insurances.

NA NA

Vimo

www.vimo.com

Information about health

insurances.

NA NA

depends on the evidence base of a set of visual

diagnostics; and plausibly, in this scope,

synchronous video communication can be used to

establish an effective link that supports service and

care delivery in healthcare system.

The study uses the design science approach,

which emphasizes that any new information

technology artifact, developed to address a key

problem, should be evaluated in a real world setting

to demonstrate its purposefulness (Hevner et al.

2004). We provide a technological framework and

design architecture to develop a customizable online

DesigninganEffectiveSocialMediaPlatformforHealthCarewithSynchronousVideoCommunication

435

healthcare social media network that can incorporate

synchronous video communication capability. Next

section will provide some background and research

context and the third section will discuss the features

needed to support the video communication portal.

The fourth section illustrates the functioning of the

portal, along with the design principles and layers

that support different types of functionalities. The

last section makes some comments on the evaluation

underway and provides concluding remarks.

2 PRIOR RESEARCH

Existing literature points out that there are several

limitations of social media for health

communications. In a recent review, Moorhead et al

(2013) point out that quality concerns, lack of

reliability of information, and blurred lines between

content producer are three major concerns about the

reliability of these platforms. However, beyond

these concerns, the most important one is the

“information overload” and “lack of validity of the

information,” and this poses a bigger challenge to

the use of the social media for meaningful purposes

(Adams 2010a; b). Lack of guidelines may

misinform the public on how to correctly apply

information found online to their personal health

situation, thus posing a danger in promulgating

adverse health impact or consequences (Freeman

and Chapman 2007). These reasons also deter

providers not to participate in a social network site,

especially when there is a higher likelihood that the

text based information may result in a greater risk.

Thus, limited evidence on to what extent online

communities are effective in positively impacting

people’s health (Colineau and Paris 2010), and how

effective social media is in communicating health

related information to patients, are some inhibiting

factors for providers from actively participating in

online social health networking portals (Kim 2009).

Against these concerns, existing studies have

suggested three plausible alternatives for greater

provider engagement (Lagu, et al., 2010). First,

similar to traditional Internet sites, there is a need for

greater interactivity in the social media for patients

to upload information regardless of quality. The

information posted will be at least more realistic and

meaningful to the patients (Adams 2010b) and this

might help providers glean useful insights into

patients’ needs and concerns. Mikki Nasch, the co-

founder of AchieveMint recently discussed their use

of social medial platform to let patients voluntarily

interact with either, so healthcare providers can gain

useful information on patient adherence to certain

desired behaviour, using Mashup technologies (Polz

et al. 2013). Second, reliability concerns can be

mitigated if the social media communication and

relevant information extraction can be given to third

party agencies (Sneha and Varshney 2009), thus

allowing healthcare providers to focus on

developing appropriate strategies based on this data.

In the above example, AchiveMint is the third party

used by Sanofi-Aventis, a pharmaceutical firm. The

third, and the most important, suggestion is to

improve “media richness” by making the

information communicated contextually relevant to

the situation at hand (Kaplan and Haenlein 2010).

In support of the third suggestion, a novel artifact

that supports synchronous video communication

(SVC) is proposed in this research paper. Table 1

summarizes many social media interaction

environments that support health care related

interactions and none of these, to our knowledge,

have the provision for such synchronous video

communication functionality.

Synchronous video communication (SVC) is not

new concept in the emerging Web 2.0 context.

Indeed there are a number of applications that

provide SVC services, albeit not within social media

platforms. Applications such as Skype, Voodoo,

Google Chat with Video do facilitate multi-party

video conferencing features. While it may be argued

that, the social media users can always use these

“external third party” solutions for synchronous

communication. However, in the health care

context, knowledge base diagnostic or information

sharing approach requires an integrated platform as

switching between different applications is

cumbersome to users. Both in the patient-physician

context as well as patient-patient context, the

requirement of a well-integrated system to support

secure communication, search capabilities to find

topics of interest, connect with others, and to allow

for business work-flow integration will facilitate

efficient and effective care management. To

summarize, although social media applications and

use are growing in healthcare, but a significant

design gap remains in the existing social media sites.

They are not focused on synchronous video based

communication, and that perhaps is posing a

challenge for a provider-side adoption of the social

media to deliver care. We suggest a design and

demonstrate implementation of synchronous video

communication (SVC) in a social media portal. In

this regard, the next section develops design features

needed to support the SVC application in a

healthcare setting using social media environment.

HEALTHINF2014-InternationalConferenceonHealthInformatics

436

3 USER REQUIREMENTS

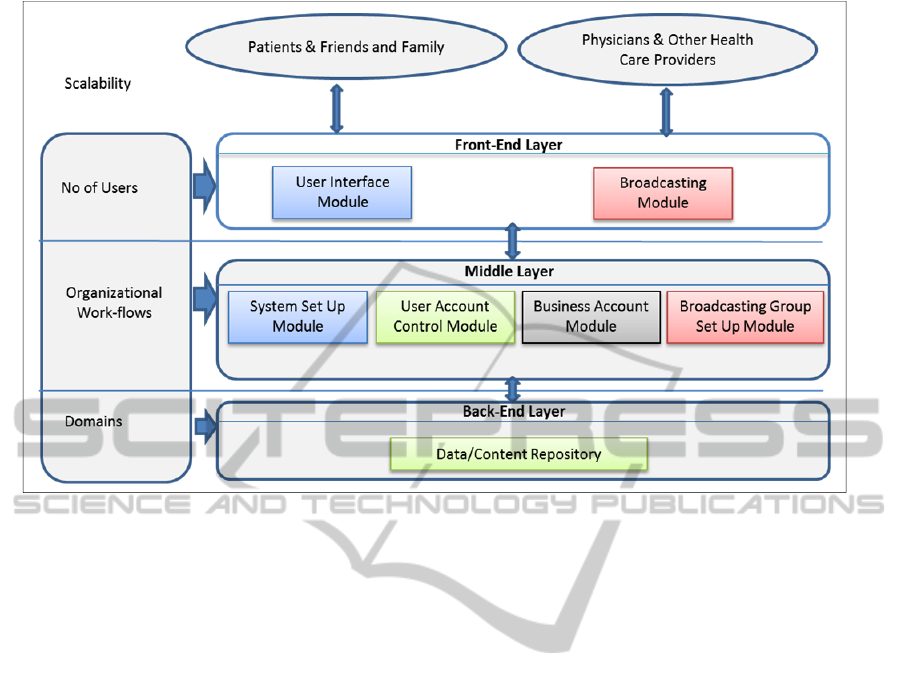

The synchronous video communication (SVC),

designed to support health related discussions in a

social media context, uses features along three

layers: input (front-end), application (middle) and

database (back-end layers) (see Figure 1). The front-

end layer is designed to support two types of

stakeholders: (1) users, consisting of patients, friend

and family and (2) providers, consisting of

physician, nursing staff, provider organization

employees. The goal here is to provide easy and

secure access to the video content, and support the

associated social media interaction between patients

and providers. The middle layer is designed to

support the workflow management necessary for the

distribution of the content to meet care provider’s

policy needs and interaction of the content to meet

the healthcare needs of the patient. The back-end

layer is designed to support the creation,

customization and search functionalities of the SVC.

3.1 User Interface Requirements

The user interface requirements of the front-end

layer focus on two access related features: ease of

access and secure access. The ease of access in SVC

calls for both effectiveness of information and

mobility for users. The interface needs to be simple

and intuitive, as many healthcare sites are accessed

by elderly people. The interface needs to limit the

degree of scrolling and allow the patients to preview

the content and community they are interacting with

before they enter the site. In addition, the system

needs to support many typical communication

features such as discussion forums, instant

messaging and others such as those discussed in

physician rating sites (Lagu et al. 2010).

The mobility feature in this context is the user

access at any time and from any place to the portal,

irrespective of geographical location, technology

platform and medium of internet access. Patient

access to the system is critical as this is key to the

synchronous communication. The focus should be

ubiquitous access and patient-centric, so that patient

can connect with his/her friends for chat, review

health care data, connect with - and engage in -

consultation with a physician, etc. In other words,

the technology should support access from any

platform (desktop to mobile devices), and from any

location (work place, home, and outside of home).

Secure access to the site should include authentic

login features and other controls needed when

information is shared with others in public or private

interaction mode. There is negative relationship

between privacy concerns and willingness to

disclose information when requests come from

government/public health agencies vis-à-vis

hospitals or pharmaceutical companies (Anderson

and Agarwal 2011). In addition, patients trust non-

profit hospitals more than for-profit organizations.

Therefore, it is critical that appropriate

privacy/access control features are incorporated and

screens/views are limited based on the role the group

or an individual user (patient, physician, face book

involved in the discussion, etc.) may play.

Moreover, social media sites with chatting or

blogging capability have to detect and prevent the

use of profanity or obscene words. Thus, the

proposed system should support a robust set of

secure access mechanisms, including password

controls, role based access, and administration

privileges upon authentication. Finally, Secure

Sockets Layer (SSL) technology for encrypted link

between a server and a client may be needed, given

that the social media platform will operate from

different server locations.

3.2 Database Requirement

The back end layer includes a database engine that is

designed to support content creation or

development, content customization and content

search. The health care content in healthcare is

changing rapidly and physicians and other health

care providers may update the content used by

patients at a more frequent rate. Thus, ease of update

of content becomes critical to maintain the

effectiveness of the site. Furthermore, given that the

context of patient inquiry will change with time,

there should be provisions for customization by

patients, so that patients can select the right

healthcare domain to share it with others and

consult/pose questions to physicians. Finally, as the

content stored grows over time, ability to quickly

and effectively search and select the content that

patients need becomes an important criteria for the

design of the system.

3.3 Application Requirements

The application layer is designed to address three

needs: (1) alignment/support with organizational

workflows, (2) accommodation of domain diversity,

and (3) scale up to meet the increase of users.

First, alignment with organizational workflows is

crucial since the system should be flexible enough to

support the needs of healthcare providers to

DesigninganEffectiveSocialMediaPlatformforHealthCarewithSynchronousVideoCommunication

437

Figure 1: Design Features of the SVC-Social Media Framework.

support care consultation and knowledge

dissemination. Providers may want to schedule

weekly broadcasting time for certain type of care

related communication, or simply make physicians

available for consultation at a certain time, for

patients to interact with the physicians. The platform

should provide flexibility and customizability so that

it is used by physicians from differing streams with

distinct needs. Apparently, a common theme

amongst care delivery is the need of synchronous

consultation or synchronous discussion, relying on a

repository of evidence based knowledge system.

We try to implement the synchronous discussion

part, and make use of pre-recorded videos for

creation of the knowledge system along with text

based repositories.

Second, although the end goal is to develop a

synchronous video conference (SVC) portal for

health domain, the platform should provide

opportunity to support communication for various

other domains than healthcare. For example, in

addressing pain management issues and related care,

the system may support synchronous interaction

between patients and physician, while in the case of

patients with obesity and diabetes related illnesses,

the system may focus on social interaction among

patients groups to support behavior modification.

Yet, in other cases such as heart patients in a nursing

home, the system may provide patient-family

interaction with only an asynchronous display of

care related information provided by the physician.

For smoking cessation management programs, the

system may rely on both group and incentive based

interventions. While the requirements for these

health related issues may be different, but a

generalizable application layer that can support

dynamically the interface protocol and content

changes with minimal programming should be the

objective of the system. For example, adding videos

and indexing these for easy use, as well providing

content-providers the ability to promote these to

different groups is useful.

Finally, as demonstrated in many social media

sites, the data and the number of users on any social

media typically start small but may soon grow

exponentially depending on the popularity of the

site. In addition, any site that uses videos requires a

great deal of bandwidth and storage to handle a large

amount of data being transmitted. Although

organizations go through a rigorous capacity

planning or other pre-estimation process, it is very

common to start small and expand as demand

increases. In this regard, it is important to design the

architecture to support the scalability; that we have

accommodated in the design for scalability.

Thus, to summarize, we user interface

requirements of a synchronous video communication

feature design for a social media platform need to

accommodate some salient features in its front-,

middle- and back- end layers. While addressing the

HEALTHINF2014-InternationalConferenceonHealthInformatics

438

design parameters for these features, the next section

will provide elements embedded in the system

architecture to support the SVC and illustrate its use

with some sample screen shots of the implemented

design in an alpha-developed social media site.

4 DESIGN ARCHITECTURE

The system design architecture has the objective to

support the design features discussed in the previous

section. Figure 1 provides, under each layer,

specific system design elements to support the

synchronous video communication in social media.

The architecture consists of several components in

the three layers: (1) front-end layer, (2) middle layer

and (3) back-end layer.

4.1 Front-end Layer

The front-end layer consists of two major modules:

(a) user interface module and (b) broadcasting

module. The user interface module is responsible

for providing easy-to-use interface, user

authentication for secured access or search options.

The user interface module allows the users to log in

and browse, search for friends, or invite a group to

join through web browsers. The client’s user

interface is automatically rendered by the changes

made to the system set up module in the middle

layer. Through the access control mechanism built

in, the user account control module of the middle

layer displays different set of menus depending on

the type of user account: broadcast owner or

broadcast recipient. To build dynamic and

interactive user interfaces, a combination of

Javascript and AJAX on top of HTML and CSS

have been used. The home screen consists of three

panels: top menu panel, left menu panel, and

outcome display panel in the middle.

The broadcasting module is responsible for

creating and customizing the broadcasting contents.

This module is only available for the account

registered as a broadcast owner. Once the

broadcasting feature is set up by the middle layer,

the owner - health professional - can customize

broadcasting settings. The system is designed to

leave zero-foot print on the client site by having the

console program download from the back-end server

the needed information, wherever it is needed. Once

it is downloaded, the console program indicates

whether it is on air or not, and displays the same

screen users see on their website.

Using the console program in the broadcasting

module, health professionals can easily set up

weekly live video schedules and customize the

contents by uploading any recoded video or image

materials they want to share with others. Once the

broadcast is made to the public, all interested can

interact with the health professional and engage in

public chat or even private chat. By clicking a user

name on the user list, users can see the profile of the

person of interest or send a private chat request for a

confidential communication. If the person accepts it,

they can have a private chat that others cannot see.

This feature is extremely critical in healthcare

environment that deals with confidential information

on many occasions. This broadcasting module uses

Adobe’s Flash to stream videos and audios at the

user site as it uses less bandwidth to stream videos.

4.2 Middle Layer

The middle layer has four major modules: (a) the

system set up module, (b) the user account control

module, (c) the business account module, and (d) the

broadcasting group set up module.

The system set up module is responsible for

defining parameters that will be passed to the

browser to control the behavior of the application. It

also provides a mechanism to set up the interface

including the search menu. All the changes made

through this module are saved into the data/content

repository of the back-end layer.

The user account control module provides a

mechanism for users to set up accounts. It also

provides a way to block an account that violates

established policies set up by the SVC portal. It also

communicates with the broadcasting set up module

to determine the access control of the broadcaster

account.

Business account module helps to implement

organizational workflows and business processes.

For example, business activities are recorded to

track the status of recruiting or contacting potential

broadcasters or any issues related to broadcasting,

etc.

The broadcasting group set up module interacts

with the video streaming service and builds a

container that includes all necessary functionalities

including live video broadcasting, scheduling, off-

line recoded video, and other training material

management. Once the broadcasting group is set up

through this module, the container is created and

stored into data/content repository with a unique

identifier. Because this identifier is associated with

the broadcaster (owner) account, the broadcaster can

DesigninganEffectiveSocialMediaPlatformforHealthCarewithSynchronousVideoCommunication

439

easily retrieve the container from anywhere to

broadcast or change parameters through the

broadcasting module implemented into the

broadcasting console program. This module

contains the steps needed to build a chat module and

link a chat window to the designated video

broadcasted window.

4.3 Back-end Layer

This layer is a repository that stores all the data and

the containers made by modules in the front-end

layer and the middle layer. This repository is

designed and structured so that the stored scripts,

templates, or objects can be shared and reused

especially by the broadcasting group set up module

of the middle layer and the broadcasting module of

the front-end layer. When a new broadcasting group

is created, a separate container for the group is

created in this repository. In addition, when

parameters are changed in the front-end layer, these

changes are updated into the flash script stored in the

corresponding container. Most of the data in this

repository are represented by the relational data

model and built on MySQL program. The chat

content and user list of each group are also stored

into the repository, and constantly updated by the

broadcasting module of the front-end layer.

5 CONCLUSIONS

An evaluation of this framework in support of pain

management is underway. The proposed system

provides several key benefits that go beyond one

provider or one disease setting. First, the system can

provide information sharing platform with real-time

interactivity between the parties. Second, the system

design is centered around providing flexibility of

building communities or targeted markets amongst

parties based on their interests, while providing

control to the information disseminated. Third, the

portal can make expert information available in

public or in private, depending on the modalities of

operation. Because the information will be provided

by expert’s live video rather than simple blogging or

email communication, the patients or information

recipients’ satisfaction and trust will increase, as the

systems allows for two-way real-time

communication between the parties through live

chat. Besides evaluation, future work will continue

to look at leveraging the benefits of synchronous

vide communication system on a broad scale.

REFERENCES

Adams, S. A. 2010a. "Blog-Based Applications and

Health Information: Two Case Studies That Illustrate

Important Questions for Consumer Health Informatics

(CHI) Research", International Journal of Medical

Informatics (79:6), pp. e89-e96.

Adams, S. A. 2010b. "Revisiting the Online Health

Information Reliability Debate in the Wake of “Web

2.0”: An Inter-Disciplinary Literature and Website

Review", International Journal of Medical Informatics

(79:6), pp. 391-400.

Anderson, C. L., and Agarwal, R. 2011. "The Digitization

of Healthcare: Boundary Risks, Emotion, and

Consumer Willingness to Disclose Personal Health

Information", Information Systems Research (22:3),

pp. 469-490.

Colineau, N., and Paris, C. 2010. "Talking About Your

Health to Strangers: Understanding the Use of Online

Social Networks by Patients", New Review of

Hypermedia and Multimedia (16:1-2), pp. 141-160.

Fox, S., and Jones, S. 2009. "The Social Life of Health

Information," pp. 2009-2012.

Freeman, B., and Chapman, S. 2007. "Is “Youtube”

Telling or Selling You Something? Tobacco Content

on the Youtube Video-Sharing Website", Tobacco

Control (16:3), 2007, pp. 207-210.

Frost, J. H., and Massagli, M. P. 2008. "Social Uses of

Personal Health Information within Patientslikeme, an

Online Patient Community: What Can Happen When

Patients Have Access to One Another’s Data",

Journal of Medical Internet Research (10:3).

Giustini, D. 2006. "How Web 2.0 Is Changing Medicine",

BMJ (333:7582), pp. 1283-1284.

Green, B., and Hope, A. 2010. "Promoting Clinical

Competence Using Social Media", Nurse Educator

(35:3), pp. 127-129.

Hawn, C. 2009. "Take Two Aspirin and Tweet Me in the

Morning: How Twitter, Facebook, and Other Social

Media Are Reshaping Health Care", Health Affairs

(28:2), pp. 361-368.

Heidelberger, C. A. 2011. "Health Care Professionals’ Use

of Online Social Networks, Available at:

http://cahdsu.wordpress.com/2011/04/07/Infs-892-

Health-Care-Professionals-Use-of-Online-Social-

Networks/ " Retrieved 13 October 2013.

Hevner, A. R., March, S. T., Park, J., and Ram, S. 2004.

"Design Science in Information Systems Research",

MIS Quarterly (28:1), pp. 75-105.

Hillestad, R., Bigelow, J., Bower, A., Girosi, F., Meili, R.,

Scoville, R., and Taylor, R. 2005. "Can Electronic

Medical Record Systems Transform Health Care?

Potential Health Benefits, Savings, and Costs", Health

Affairs (24:5), pp. 1103-1117.

Kaplan, A. M., and Haenlein, M. 2010. "Users of the

World, Unite! The Challenges and Opportunities of

Social Media", Business Horizons (53:1), pp. 59-68.

Kim, S. 2009. "Content Analysis of Cancer Blog Posts",

Journal of the Medical Library Association : JMLA

(97:4), pp. 260-266.

HEALTHINF2014-InternationalConferenceonHealthInformatics

440

Lagu, T., Hannon, N., Rothberg, M., and Lindenauer, P.

2010. "Patients’ Evaluations of Health Care Providers

in the Era of Social Networking: An Analysis of

Physician-Rating Websites", Journal of General

Internal Medicine (25:9), pp. 942-946.

Landro, L. 2006. "Social Networking Comes to Health

Care", Wall Street Journal (27).

McNab, C. 2009. "What Social Media Offers to Health

Professionals and Citizens, URL: http://

www.who.int/Bulletin/Volumes/87/8/09-066712/En.".

Moorhead, S. A., Hazlett, D. E., Harrison, L., Carroll, J.

K., Irwin, A., and Hoving, C. 2013. "A New

Dimension of Health Care: Systematic Review of the

Uses, Benefits, and Limitations of Social Media for

Health Communication", Journal of Medical Internet

Research (15:4) pp 11-25.

Polz, M., Sanofi-Aventis, and Mikki Nasch, A. 2013.

"Smart Data Is the Key to Scaleable Healthcare

Solutions," in: Big Data Symposium. Eller College of

Management, Arizona.

Sneha, S., and Varshney, U. 2009. "Enabling Ubiquitous

Patient Monitoring: Model, Decision Protocols,

Opportunities and Challenges", Decision Support

Systems (46:3), pp. 606-619.

Thackeray, R., Neiger, B. L., Hanson, C. L., and

McKenzie, J. F. 2008. "Enhancing Promotional

Strategies within Social Marketing Programs: Use of

Web 2.0 Social Media", Health Promotion Practice

(9:4), pp. 338-343.

DesigninganEffectiveSocialMediaPlatformforHealthCarewithSynchronousVideoCommunication

441