A Video Competition to Promote Informal Engagement with

Pedagogical Topics in a School Community

José Alberto Lencastre

1

, Clara Coutinho

1

, Sara Cruz

1

, Celestino Magalhães

1

, João Casal

2

, Rui José

2

,

Gill Clough

3

and Anne Adams

3

1

Institute of Education, University of Minho, Campus de Gualtar, 4710-057 Braga, Portugal

2

Centro Algoritmi, University of Minho, Campus de Azurém, 4800-058 Guimarães, Portugal

3

Institute of Educational Technology, Open University, Walton Hall, Milton Keynes, MK7 6AA, U.K.

Keywords: Videos, Public Display System, Technology-enhanced Learning.

Abstract: This paper presents a study developed in the scope of a larger project that aims to understand how video

editing and content sharing in public displays can be used at schools to promote the informal engagement of

students with curricular contents that are essential to foster future learning. The study involved a video

competition where students were invited to create videos around specific pedagogical topics. These videos

were subsequently presented in the public display at the school, and students could use a mobile application

to rate, create comments or just bookmark the videos. Findings suggest that students are receptive to

creating videos and sharing them in public displays. However, the results also show that few students that

used the application to interact with the content. Many reasons for this are presented such as unawareness

that the display is interactive ‘because it seems like a regular TV’, too small a number of interesting videos

shown during the video contest. Particular barriers included not owning a mobile device capable of

interacting, and the limitation of the large screen which does not allow searching ‘the videos we like’, as

YouTube seems to do.

1 INTRODUCTION

Video is becoming increasingly important as a

learning technology. The use of video as a

pedagogical resource has been shown to achieve

significant pedagogical results. It is seen as playing

an important role in the educational process by

allowing the teacher to diversify teaching practices

(Jordan, 2012). In this work, we also address the

pedagogical use of video, but we focus on the

broader role that video creation and presentation can

have to promote curiosity and engagement with

pedagogical topics. As suggested by Goodyear

(2011), there is a shift in our sense of the spaces and

contexts in which education takes place, as different

learning activities are becoming more commonly

distributed across a variety of contexts. We focus on

the boundary between the video as a pedagogical

and creative performance for the author and the

video as a social object for the educational

community.

Our study is part of an on-going research project,

called JuxtaLearn, which aims to promote students'

curiosity in science and technology through creative

filmmaking, collaborative editing activities, and

content sharing. The idea is to identify their learning

difficulties or ‘threshold concepts’, i.e. concepts that

constitute major learning barriers, and facilitate the

learners understanding through the creation and

sharing of explanatory videos. Meyer and Land

(2003) describe ‘threshold concepts’ as a barrier to

comprehension that once overcome opens a new

knowledge about the subject. The JuxtaLearn

process uses the collaborative video editing and

sharing to foster students’ curiosity in ‘tricky

topics’, helping them to move towards a deeper

understanding (Adams et al., 2013). We will refer to

these topics as ‘tricky topics’, as this was the term

used during the work with teachers. These videos,

together with additional data, such as quizzes, and

the subsequent engagement with viewers is what we

call a video performance. Digital displays in the

public space of school can play an important role as

a medium for informal learning by extending those

video performances to a new learning context,

promoting curiosity with the videos and their content

334

Lencastre J., Coutinho C., Cruz S., Magalhães C., Casal J., José R., Clough G. and Adams A..

A Video Competition to Promote Informal Engagement with Pedagogical Topics in a School Community.

DOI: 10.5220/0005450403340340

In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2015), pages 334-340

ISBN: 978-989-758-107-6

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

(Otero et al., 2013), fostering discussion around

those topics. According to Lencastre, Coutinho,

Casal and José (2014a,b,c), public displays in an

educational context can be a simple and effective

way to generate shared experiences in schools.

Being interactive displays, the screens can be used to

promote students' curiosity about the content,

favouring the process of learning the content

presented on the screen.

In this work, we report on a study that aimed to

understand the extent to which the presentation of

locally sourced pedagogical videos on a public

display at a communal space of the school is able to

promote engagement around the videos and the

topics they represent. The goals that guided the

research project were formulated as follows: i) To

understand the pedagogical relevance of the video

creation process; ii) To foster student's curiosity in

complex concepts through educational videos, iii)

To generate a collection of videos that can be shared

on the public display in order to study the

mechanisms of interaction with the platform.

The study involved a video competition where

students were invited to create videos around

specific ‘tricky topics’. These videos were

subsequently presented in the public displays and

students could use a mobile application to rate,

create comments or simply bookmark them.

2 RELATED WORK

The use of video as a pedagogical resource in school

is not new and has been used with proven results

(Jordan, 2012). The video may play an important

role in the educational process as it allows the

student to have participatory role, a more engaging

learning, and facilitating the acquisition of

knowledge. An example is YouTube that has a high

potential to improve the quality of the reflection in

the classroom (Bell, 2013; Caetano and Falkembach,

2007), and can increase the enthusiasm and students'

motivation (Heitink et al., 2012), through more

efficient understanding (Khalid and Muhammad,

2012).

Interaction with public displays is mostly

expected to occur as part of a public setting where

many people may be present, typically carrying out

multiple activities and having their own goals and

context. Therefore, for interaction to occur, the

display must be able to attract and manage people’s

attention. However, engaging users with interactive

public displays is known to be a challenging task.

Brignull and Rogers (2003) reported that ‘a major

problem that has been observed with this new form

of public interaction is the resistance by the public to

participate’. Kukka, Oja, Kostakos, Gonçalves, and

Ojala (2013) studied how this barrier to interaction

(the ‘first click’), can be overcome. Previous

research has also identified the display blindness

effect (Müller et al., 2009), where people look at the

display, but do not see its content. Based on previous

experiences that created the expectation that content

is not relevant, people just learn to filter it. Müller,

Wilmsmann, Exeler, Buzeck, Schmidt, Jay and

Krüger (2009) pointed out that the majority of users

only look at the displays if they have the expectation

of seeing relevant content. The fear of looking silly

while interacting with the display, especially in

gestural interfaces, has also been pointed out as

another barrier to interaction (Brignull and Rogers,

2003). Müller, Walter, Bailly, Nischt, and Alt (2012)

also explore the issue of noticing the display

interactivity as other barrier for interaction.

In the specific study presented in this paper the

strategy to seed the system with locally relevant

videos, consisted in the promotion of a pedagogical

video competition where students created a number

of videos across different scientific areas. The goal

was to overcome the display blindness effect (Müller

et al., 2009) by offering users content that they could

more easily identify with and thus perceive as more

relevant. To allow users to notice interactivity

(Müller et al., 2012), we created informative digital

posters that were being exhibited on the display

regularly. The posters have also been posted on the

schools’ institutional Facebook.

Besides the best educational video award, and in

order to raise the interaction with the public display,

another prize was given to the video that generated

the most interaction.

3 METHOD

This study was strongly anchored on the video

competition that took place in a secondary school in

Portugal. The study also included the identification

of ‘tricky topics’ with teachers and the public

presentation of the videos in the communal space of

the school.

Different methods were applied in order to

collect the data: (i) semi-structured interviews with

teachers from different departments, (ii) system logs

on the platform, (iii) a diary to collect direct

observations, (iv) a grid to evaluate the pedagogical

relevance of the videos, and (v) a group interview

with the students to get a qualitative assessment and

AVideoCompetitiontoPromoteInformalEngagementwithPedagogicalTopicsinaSchoolCommunity

335

to understand their perceptions about the whole

process.

3.1 Participants

Thirteen teachers of a public school (9 females and 4

males) participated in this study. A total of 44

students (ages between 16 and 18) from different

school years took part in this event in a total of 22

teams. Other ten participating teachers from

different curricular subjects accompanied the teams

during the video creation process (scientific

mentors). The video contest jury consisted of eight

schoolteachers, one from each of the subject areas of

the submitted videos, one member from the school

board, and a member from the University of Minho

team.

3.2 Identifying the ‘Tricky Topics’

The first step in the research process was the

identification by the teachers of the pedagogical

topics that could serve as themes for the videos.

These were expected to be ‘tricky topics’ that

represented key learning barriers within the

respective subjects. To identify ‘tricky topics’, we

conducted thirteen semi-structured interviews with

teachers from several departments (e.g.,

Mathematics, Biology, Chemistry, ICT, Portuguese,

English, Arts, History, Geography, Philosophy) with

the following open questions: (1) which ‘tricky

topics’ do students usually have difficulties with? (2)

What reasons lead the student to have these

difficulties? and (3) What teaching strategies do

teachers use to help students overcome these

difficulties?

Each interview lasted approximately 15-20

minutes and was audio recorded and transcribed.

Later, a content analysis was carried out following

the guidelines of Bardin (2013). The goal was to

extract information on the ‘tricky topics’, and

associated ‘stumbling blocks’, that teachers

considered complex for students. The collected

‘tricky topics’ were then used as the list of possible

themes that the students could choose to create their

videos.

The thirteen interviews generated fifty-eight

‘tricky topics’. These topics formed the themes that

the students could choose to create the videos. From

the 44 students initially enrolled only 23 (ten girls

and thirteen boys, forming ten groups) submitted

videos to the contest.

3.3 Running the Video Competition

With the themes list ready, the video competition

was then announced through multiple channels:

flyers, student's institutional email, an official

website, Facebook, School's YouTube channel,

regular 'teasers'. The competition process involved

three main steps: (1) enrolment in the video contest;

(2) video making; and (3) presentation of the videos

in the public display at the school.

To register for the video competition, students

could fill an online questionnaire, where they

described their group (name, contact details, class

and year) and the theme they had selected for their

video. Students were then expected to go through the

process of storyboarding, filming and composing a

video performance that expresses their

understanding of the ‘tricky topic’. Especially during

the storyboard phase, they were supposed to interact

with their scientific mentor to assure the scientific

validity of their video. All submitted videos had to

be associated with at least one scientific mentor. A

questionnaire was fulfilled by these mentors who

monitored the groups in the video creation process

in order to obtain information on three main issues:

(i) if the video is scientifically correct, (ii) if it has

pedagogical potential, and (iii) if the teacher would

use the video in his own classes. This survey

included ‘closed‘ response items, by using a Likert

scale with five points (from 1 = ‘Strongly disagree’

to 5 = ‘Strongly agree’).

The videos submitted to the competition were

judged according to the following criteria: 50% for

pedagogical quality and potential to promote

understanding of the represented topic, and 50% for

multimedia quality, originality and potential to

generate curiosity. Three awards were given: 1) best

video award; 2) second video award, and 3) the

video with the most interactions generated at the

school’s public display.

3.4 Public Presentation of the Videos

The videos submitted to this competition were

publically presented to the entire school community

through a public display in the communal space of

the school. Our main interest was to analyse the

level of engagement and to measure the levels of

interactivity with the displayed videos. Thus, the

location of the display was selected in order to

capture students’ attention, as this is a space where

they hang around during breaks (see Figure 1).

The room is also a place that most students need

to walk through as they go to or return from classes,

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

336

as it is near the cafeteria.

Figure 1: Public display at the communal space of the

school, near the cafeteria.

The public display used for this study includes a

display application that renders the videos published

by students and shows some additional information

about them. In the space between videos, the

audience is informed about which video was shown

last and which are to be shown next. The application

also displays metadata associated with the videos

like title, author, rating and number of votes (see

Figure 2).

Figure 2: Screen of the public display used for this study.

Students were encouraged to engage with the videos

through the JuxtaLearn mobile app. This is part of a

discussion step in which several mechanisms are

applied to engage user participation and commenting

with the goal of augmenting the reflective facet of

the JuxtaLearn process.

The mobile application shows a content stream

with information about the recently presented

videos, giving users easy access to rate, comment or

simply access the video on YouTube. The rate

feature allows users to classify the videos. The

comment feature is to enable viewers to let the video

authors know what they think about their video

Figure 3: Mobile application.

creation. The feature ‘Know more’ leads the user to

the YouTube page of the video, which allows

personal viewing of the content or access related

videos about the same issue.

The application on the display frequently shows

information about how to download and use the

mobile application, incentivizing people to it.

In addition to the videos, at regular intervals, the

display system also runs other applications that show

school information, like news or photos of events.

The use of the mobile app generated metrics to

assess the different aspects of the system usage.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Video Creation Process

The submitted videos to the educational video

contest approached the following ‘tricky topics’: (i)

behavior of the function near the asymptote

(Mathematics), (ii) asexual reproduction (Biology),

(iii) evolution (Biology), (iv) preconception

AVideoCompetitiontoPromoteInformalEngagementwithPedagogicalTopicsinaSchoolCommunity

337

(Philosophy), (v) matrices and vectors (Technology,

programming), (vi) robotics (Technology,

programming), (vii) freedom (History), (viii)

democracy (Philosophy), (ix) asking questions

(English), and (x) starting a corporate (Secretariat).

All groups have indicated a scientific mentor,

except one group that was disqualified. According to

these teachers, all the nine videos submitted to the

contest are scientifically correct, have pedagogical

potential and therefore could be used in their

classrooms (see Table 1). This survey included

‘closed‘ response items, by using a Likert scale with

five points (from 1 = ‘Strongly disagree’ to 5 =

‘Strongly agree’).

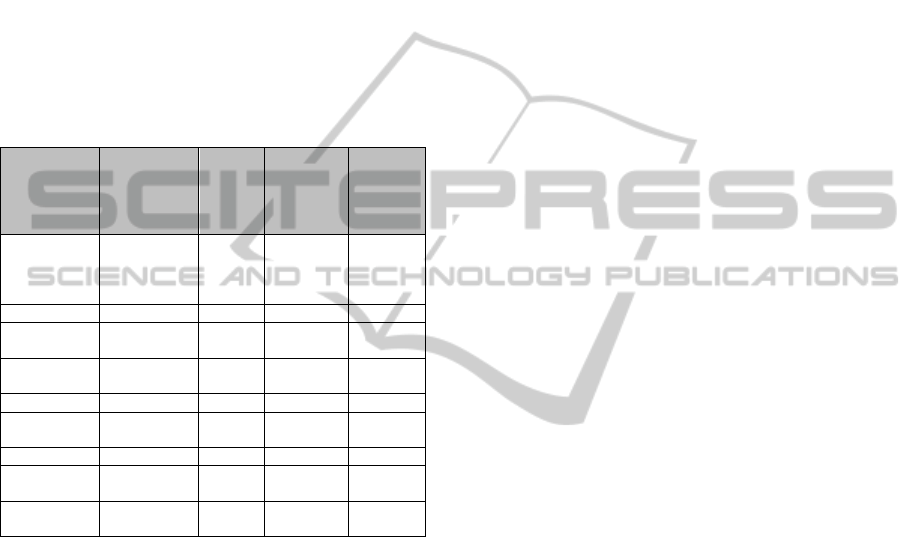

Table 1: Teachers' opinion about the videos.

Subject Themes /

’tricky

topic’

Scienti

fically

correct

Pedagogi

cal

potential

Could be

used in

the

classroo

ms

Mathematic Behavior of

the function

near the

asymptote

4 4 4

Biology Evolution 5 5 5

Biology Asexual

reproduction

5 5 5

Technology Matrices

and vectors

4 4 4

History Freedom 5 5 5

Philosophy Preconcepti

on

5 5 5

Technology Robotics 4 4 3

English Asking

questions

5 5 5

Secretariat Starting a

corporate

4 4 4

Simultaneously the jury panel made the videos'

assessment. The following links point to the

awarded videos:

- Best video award: http://youtu.be/Hbx6p_uxVQA

- Video with more interactions with the public

display:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=61qqwT1Bk

7M

4.2 Analysis of the Awarded Videos

4.2.1 Best Video

The video ‘asexual reproduction’ (Biology) begins

by explaining that reproduction is essential for the

maintenance of species, once the new beings arise

from other living creatures through mitoses. The

images show that the beings that arise by asexual

reproduction are genetically identical to each other.

The video continues illustrating the process of

asexual reproduction in different types of unicellular

organisms, although it may also occur in some

multicellular organisms. Then the video shows

similarities and differences between the various

cases of asexual reproduction.

From a pedagogical point of view, in the opinion

of the evaluators, the video allows viewers to assess

the implications of asexual reproduction in terms of

variability and survival of populations. Through the

created scenario, it is possible to understand the

hermaphroditism as a condition that does not involve

self-fertilization.

4.2.2 Video with More Interactions with the

Public Display: ’Preconception’

The video with more interactions with the public

display (36% of the total interactions) addresses the

thematic of 'preconception' (Philosophy). The actors

are students of the school's theatre group.

The video begins with the presentation of the

main characters: a class of the school and the arrival

of a new student. Next, various situations of bullying

with the new student are staged: discussions,

beatings and humiliation. In response, the new

student reacts with revolt, despair, and aggression.

Finally, the revenge, the new student fires a gun

at one of the aggressors. The film continues with the

attempted suicide of the main character and

concludes with the awareness of the wrongful act

from one of the attackers and the attacked.

According to the evaluators, the video has

potential for portraying authentic situations that can

be pedagogically framed in different disciplines and

school years. The actors gave credibility to the

performance, aspect highlighted by the jury. The

images are powerful and could be real. By having

students known to their peers, the video has

enormous potential to address ‘bullying’.

4.3 Interaction with the Videos

Regarding the logs recorded on the system, the

following results were obtained:

20 distinct users signed up (19 of which

interacted with videos);

94 interactions with videos were registered;

2 distinct users wanted to know more about

videos;

In 9 videos, users followed the YouTube link in

order to see them again or to watch related

videos.

Table 2 lists the interactions per type of production

or type of content, giving insights about which are

the video performances that foster more curiosity.

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

338

Table 2: Number of interactions per type of video

performance.

Type of production

# of

interactions

% of

interactions

Students performance 59 62,8

Scenes shot on own city 13 13,8

Content presentation 9 9,6

Based on web resources (ex:

personas talking)

5 5,3

Video tutorial alike 3 3,2

Other (ex: video contest

advertisement)

5 5,3

Total 94 100

4.4 Data Obtained from the Diary and

Group Interview

Some teams have not submitted the videos, others

didn’t involve the scientific mentor, which affected

the depth of the addressed concepts, and others

failed to explain the ‘tricky topic’ through images,

resigning from the video competition.

Generically, students had heard about the video

competition but did not link that with the videos

shown on the public display.

The students that participated saw the videos on

the public display because 'I know that my video is

being exhibited there’.

Students didn’t know that the display was

interactive because ‘the display seems just a regular

TV’ and ‘on my previous school existed TVs always

displaying stuff and people ignored them’.

Regarding the interaction mechanism implemented,

students stated that: using the smartphone to interact

‘it is a good bet’ because nowadays everything can

be done through smartphone. However, it should

allow other forms of interaction for those that do not

have smartphone: ‘I don’t have a smartphone, so I

cannot interact’.

Another downside is that smartphones require

personal authentication, not allowing anonymity.

Some students considered that a touch-sensitive

display could resolve this problem and could also

catch users attention, because ‘if I saw people

touching a display I would go there to see what it

was’, and perhaps it could foster interaction.

Finally, regarding the use of videos on

interactive public displays, students said that the

large screen did not support searching for ‘the

videos we like’, as YouTube seems to do. However,

they mentioned that ‘YouTube is meant for

individual use and a video application on public

displays is interesting for using in a social gathering

context’.

5 DISCUSSIONS AND

CONCLUSION

Data analysis showed that the video contest only

challenged a small fraction of the school population.

The activity did not work for half of the students

involved. Initially, 44 enrolled in the contest yet

only 23 completed the whole process. Some teams

failed to fully understand the ‘tricky topic’ they

chose but did not ask for scientific mentors’ help.

Others failed to explain the ‘tricky topic’ through

images and gave up.

On the other hand, the process worked very well

for the teams who finished the videos. Of these, we

can say that they were autonomous, self-motivated

and responsible. They were also sometimes too

independent and confident, because they did not

involve the scientific mentor, and this affected the

depth to which they explored the concepts they

addressed.

Regarding the pedagogical relevance of the video

creation process, results show that students can

create useful videos to be used in the classroom,

scientifically correct and with pedagogical potential.

However, the process showed that some videos were

not deep in the explanation of the topic covered.

This highlights the importance of the teachers’

involvement to promote the quality of the video.

Particularly interesting was to verify that

students like to see their peers performing on the

videos. This fact that was shown by the high level of

interactions with the videos in which the students

appeared in person. Those were the videos that

generated the most interactions. For the students

who were part of the video competition, there was

also the expectation of seeing their own videos being

exhibited.

Nevertheless, this high attention to the display

did not translate into high levels of mobile

interaction. In the interview we noticed that many

students never realized that there was this possibility

because they thought it was a regular TV. Despite

the intensive communication effort and the video

competition award that would be won by the video

with the most interactions, many students never

realized they could interact using their smartphones.

Findings suggest that students are receptive to

making videos and to sharing them in public

displays. This is important to foster curiosity around

those videos.

Further research is needed to study the

pedagogical relevance of this.

AVideoCompetitiontoPromoteInformalEngagementwithPedagogicalTopicsinaSchoolCommunity

339

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research leading to these results has received

funding from the European Community's Seventh

Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under

grant agreement no. 317964 JUXTALEARN. We

would like to thank school Escola Secundária de

Alberto Sampaio (Portugal) for their collaboration

on the technology deployment, on the promotion of

the video competition and for the authorization to

perform this research on their premises. We also

would like to thanks to Displr for the display

deployment and the assistant on the creating of the

JuxtaLearn video application.

REFERENCES

Adams, A., Rogers, Y., Coughlan, T., Van-der-Linden, J.,

Clough, G., Martin, E., Collins, T., 2013. Teenager

needs in technology enhanced learning. Workshop on

Methods of Working with Teenagers in Interaction

Design, CHI 2013, Paris: ACM Press.

Bardin, L., 2013. Content Analysis. Lisboa: Edições 70.

Bell, R., 2013. Video reflection in teacher professional

development.

http://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/22433.

Brignull, H., Rogers, Y., 2003. Enticing People to Interact

with Large Public Displays in Public Spaces.

International Conference on Human-Computer

Interaction INTERACT 2003, 17–24.

Caetano, S. Falkembach, G., 2007. Youtube: uma opção

para uso do vídeo no EAD. RENOTE – Revista da

Novas Tecnologias de Educação, Julho, 1-10.

Goodyear, P., 2011. Emerging Methodological Challenges

for Educational Research. In Methodological Choice

and Design, 253-266.

Heitink, M., Fisser, P., McKenney, S., 2012. Learning

Literacy and Content Through Video Activities in

Primary Education. In P. Resta (Ed.), Proceedings of

Society for Information Technology & Teacher

Education International Conference 2012 (pp. 1363-

1369). Chesapeake, VA: AACE.

Jordan, L., 2012. Video for peer feedback and reflection:

embedding mainstream engagement into learning and

teaching practice, Research in Learning Technology,

vol. 20, 16-25.

Khalid, A., Muhammad, K., 2012. The use of YouTube in

teaching English literature: the case of Al-Majma'ah

Community College, Al-Majma'ah University (case

study). International Journal of Linguistics, 4 (4),

525-551.

Kukka, H., Oja, H., Kostakos, V., Gonçalves, J., Ojala, T.

2013. What makes you click: exploring visual signals

to entice interaction on public displays. Proceedings of

the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in

Computing Systems - CHI’13. New York: ACM Press.

Lencastre, J.A., Coutinho, C., Casal, J., José, R., 2014a.

Public Interactive Displays In Schools: Involving

Teachers In The Design And Assessment Of

Innovative Technologies. In Proceedings of World

Conference on E-Learning in Corporate, Government,

Healthcare, and Higher Education 2014, Vol. 2014,

No. 1 (pp. 1760-1769). Chesapeake, VA: AACE.

Lencastre, J.A., Coutinho, C., Casal, J., José, R., 2014b.

Pedagogical and Organizational Concerns for the

Deployment of Interactive Public Displays at Schools.

In Álvaro Rocha et al. (eds.), New Perspectives in

Information Systems and Technologies, Volume 2,

Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing

Volume 276. (pp.429-438). Springer International

Publishing Switzerland.

Lencastre, J.A., Coutinho, C., Casal, J., José, R. (2014c).

Adoption concerns for the deployment of interactive

public displays at schools. In Giovanni Vincenti and

James Braman (eds.), Journal EAI Endorsed

Transactions on e-Learning 14(4): e6 , 1-7. ICST.

Meyer, J., Land, R., 2003. Threshold Concepts and

troublesome knowledge: linkages to ways of thinking

and practising within the disciplines (pp. 412-424). In

Rust, C. (Ed.) Improving student Learning - Theory

and Practice Ten Years on. Oxford: Oxford Centre for

Staff and Learning Development (OCSLD).

Müller, J., Walter, R., Bailly, G., Nischt, M., Alt, F., 2012.

Looking glass: A Field Study on Noticing Interactivity

of a Shop Window. Proceedings of the 2012 ACM

annual conference on Human Factors in Computing

Systems - CHI ’12 (p. 297). New York: ACM Press.

Müller, J., Wilmsmann, D., Exeler, J., Buzeck, M.,

Schmidt, A., Jay, T., Krüger, A., 2009. Display

Blindness: The Effect of Expectations on Attention

towards Digital Signage. Pervasive Computing: 7th

International Conference (pp. 1-8. Nara: Springer

Berlin Heidelberg.

Otero, N., Alissandrakis, A., Müller, M., Milrad, M.,

Lencastre, J.A., Casal, J., José, R., 2013. Promoting

secondary school learners’ curiosity towards science

through digital public displays. Proceedings of

International Conference on Making Sense of

Converging Media - AcademicMindTrek’13. pp. 204–

210. New York: ACM Press.

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

340