Activity Theory as a Lens to Identify Challenges in Surgical Skills

Training at Hospital Work Environment

Minna Silvennoinen

1

and Maritta Pirhonen

2

1

Agora Center, University of Jyvaskyla, Mattilanniemi 2, Jyvaskyla, Finland

2

Department of Computer Science and Information Systems, University of Jyvaskyla, Mattilanniemi 2, Jyvaskyla, Finland

Keywords: Surgical Skills Training, Activity Theory, Surgical Simulator, Expertise Development.

Abstract: In this paper the concepts from activity theory (AT) are applied for identifying the challenges and

contradictions emerging in surgical resident’s curriculum based training at hospital. AT is utilised as a lens

to identify contradictions that cause disturbances, problems, ruptures, breakdowns, and clashes which

emerge while surgical skills training is implemented in a new way at hospital. We especially aim at finding

solutions for contradictions which emerge while the new and old working culture are confronted and the

workers are required to balance themselves between the patient care demands and workplace learning

requirements. We are using the conceptual theoretical approach to describe the phenomenon of surgical

working.

1 INTRODUCTION

Surgical traditions are facing the need for radical

changes. Throughout the history, the method of

teaching and learning surgery has been the

apprentice model in which surgical residents follow

specialist surgeons at work and develop their skills

with the “see-one, do–one” method while gradually

progressing to become as independent physicians.

The learning opportunities and method are

extremely workplace dependent and situationally

affected by each hospital’s working culture and the

supervising senior’s guidance and work duties. Now,

the new development of computer based simulators

and skill requirements of video-assisted surgery

have challenged this traditional way of mentoring

residents learning (Gallagher and O'Sullivan 2012,

Reznick 2006). The arguments favourable to

operating skills curriculum which utilises newest

technology, surgical simulators, have forced also the

hospitals to consider their learning and teaching

traditions in a new way (Aggarwal et al. 2006).

Simulators have already proven to significantly

increase the efficiency of skills learning, they are a

good investment into error-preventive actions and

cost reduction relating highly expensive surgical

complications and should be used as mandatory part

in training from patient safety reasons (Reznick

2006). However, there are various views on how

resident education at hospitals should be arranged

(Hammoud et al. 2008). Even though the

development of surgical computer-based simulators

has been rapid, these learning tools are still not

utilized systematically in surgical training in

Finland, why? Previous research has found that

implementation of a curriculum based training at

hospital is not without problems (Silvennoinen et al.

2011 and 2012, van Dongen 2008). Hospitals are not

designed for learning; instead they are built for

taking care of patients. The problems in

implementation process might be caused by the fact

that even though the need for making workplaces

effective learning environments exists, it requires a

clear vision about the best possible learning structure

within each workplace (Billett 2000). In order to

implement new training models which will bring

possible rather radical change to the old traditional

training culture, we should form clear vision of both

the context and the phenomenon.

Alan Bleakley (2011) suggests models of socio-

cultural learning theories to be used in explaining

surgical learning at work. This activity partially is

seen through the model of communities of practice

by Lave and Wenger (1991), as participation in a

highly context-situated and dependent work-based

activity. Bleakley (2011) also sees that the actor-

network theory by Latour (1996) and activity theory

by Engeström (1987) can be used for competence

455

Silvennoinen M. and Pirhonen M..

Activity Theory as a Lens to Identify Challenges in Surgical Skills Training at Hospital Work Environment.

DOI: 10.5220/0005497204550462

In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2015), pages 455-462

ISBN: 978-989-758-108-3

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

development discussion. The advantages of AT in

the role of explaining the phenomenon is the

dynamic nature of learning activities, an activity

system (surgical residents training at hospital),

which is focused on achieving the same goal but still

conflicts can be produced (Bleakley 2011). The

social theories of learning are important in observing

activities where the impact of the team in the

learning process is highly important (Fry 2011). The

strength of AT is that it allows for breaking down

the structure of an activity into smaller categorical

elements (Basharina, 2007), and to identify

contradictions and structural tensions of the activity

(Engeström, 1995; Engeström, 2001). Contradictions

are not simply conflicts or problems but they are

structural tensions that have been historically

accumulated within and between activity systems

(Engeström 2001, 137). The identication of

contradictions in an activity system helps focusing

the efforts on the root causes of problems. When

contradictions arise, or when they are observed, they

expose dynamics, inefficiencies, and importantly,

opportunities for a change (Helle 2000).

In this article, surgical training as a workplace

learning activity at hospital is explored. We utilise

AT (Engeström 1987, 2001) as a lens to identify and

explore the challenges which emerge while surgical

skills training is implemented in a new way at

hospital. We especially aim at finding solutions for

contradictions which emerge while the new and old

working culture are confronted and the workers are

required to balance themselves between the patient

care demands and workplace learning requirements.

This paper is organized as follows. First, we

present the background on the requirements needed

for surgical work. Then requirements for enhancing

surgical learning at work are presented. This is

followed by the brief description of activity theory

and the description of the surgical training program

in a hospital context as an activity in AT. Finally,

identified contradictions and solutions are presented.

2 SURGEONS PROFESSIONAL

REQUIREMENTS AT

HOSPITAL IN THE CONTEXT

OF LAPAROSCOPY

Surgical work requires considerable psychomotor

skills, critical thinking abilities and decision-making

skills, a great deal of medical knowledge to recall

and apply as well as situational awareness to be able

to react rapidly to changing situations (Norman et al.

2006). Technical skills and dexterity are seen as

important for safe surgery, but from a patient safety

perspective, in order to maintain surgical expertise,

great deal of non-technical proficiency is also

needed (Yule et al. 2008, Yule and Patterson-Brown

2012). Surgeons are leaders of an operation team

which requires also responsibilities and social

abilities, so besides the technical skills, also the

cognitive and interpersonal abilities like team

working and decision making skills are needed

(Yule et al. 2008, Yule and Patterson-Brown 2012).

While skills and learning demands in modern

healthcare tends to increase, at the same time the

surgical residency time at hospitals has been

shortened as a result of new European Working

Time Directive (Bleakley 2011). Many surgeons and

senior residents have therefore concerns that

graduating residents are not anymore fully prepared

for independent work immediately after graduation

(Britt et al. 2009). In Finland the residency period

also contains a nine-month period of training in

general medicine, which does not enhance surgical

skills and surgical residents have around five years’

time to develop their specialised expertise.

The awareness of the surgical skill challenges

especially relating abdominal area video-assisted

procedures, laparoscopies has made it topical target

for research and curriculum implementation. The

technique is very popular, it needs a very short sick

leave, 7-10 days, and most of the patients are able to

go home on the operation day (Satava 2011). There

is however concerns relating increased training

requirements since the complication rates of these

procedures remain relatively high compared to open

surgeries due to various skill demands (Subramonian

et al. 2004). In video-assisted operation, surgeons

have limited visual and haptic information compared

to the open surgical technique where the incision is

larger and the visual field is normal, not transmitted

by camera and surgeons can touch the tissues with

hands, not only with long thin instruments (Van

Veelen et al. 2003).

3 IDENTIFIED REQUIREMENTS

FOR ENHANCING SURGICAL

WORKPLACE LEARNING

Surgical residents learn most of the operating skills

during their residency time while working in

hospitals. It is notable from the point of view of

education and learning that this obviously very

important period includes no structured curriculum.

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

456

Therefore a great deal of attention needs to be paid

on how resident’s education during hospital work

should be implemented in a successful way.

Making workplaces effective learning

environments is an interest in many fields today

including healthcare, which means creating

meaningful opportunities to facilitate skills and

knowledge development at work (Van De Wiel et al.

2011). Learning at work is not obvious or automatic,

but workplaces should actually be designed to

promote learning (Ellström et al. 2008). Workplaces

vary a lot in how they enable, support or constrain

learning, which effects on learning opportunities and

execution (Tynjälä 2008). The ‘expansive learning

environments’ provide the best possibilities for both

organisational and individual development as well as

their integration (Fuller et al. 2004). The list of the

issues identified on organisations that are fostering

an expansive workplace learning approach to

workforce development can be shortly listed as

follows according to Fuller et al. 2004, Fuller and

Unvin 2010:

• Workforce development is used as a vehicle for

aligning the goals of developing the individual and

organisational capability

• Organisational recognition of and support for workers

as learners - given time to become full members of

the community through gradual transition, having a

vision of workplace learning such as providing

chances to learn new skills/jobs and access to range of

qualifications.

• Managers given time (and resources) to support

workforce development and facilitate workplace

learning and individual development

• Skills and knowledge widely distributed through

workplace—multi-dimensional view of expertise;

valuing expertise, high trust

• Workers given discretion to make judgments and

contribute to decision-making

• Participation in different communities of practice

inside and outside the workplace is encouraged—

job/team boundaries can be crossed, cross-boundary

communication encouraged and identity extended

• Planned time off-the-job for reflection and deeper

learning beyond immediate job requirements.

In a context of this study, fostering surgical

expertise development at a hospital would require a

vision and development of both organisation and

individuals through workplace learning. As an

example, this would mean a curriculum developed

for the surgical residents. It would also mean

hospital organisations and managers recognition of

and support for surgeons as learners not just as a

workforce, making commitments to chances and

organising time for skills development and reflection

both on- and off-the-job during the courses, high

appreciation towards expert laparoscopists, but still

fostering cross-boundary communication within

surgical teams.

There is still a shortage of research on how the

medical experience and learning at work should be

structured to enhance skills and knowledge

development optimally (Norman et al. 2006, Van De

Wiel et al. 2011) Employees should be provided

opportunities to acknowledge and utilize the

learning situations at work, and the managers should

be provided with adequate competences to organise

and lead workplace learning (Ellström et al. 2008).

Learning task or curriculum-based learning

assignment within hospital alongside the resident’s

normal work, is similar that Tynjälä calls on-the-job

learning (Tynjälä 2008), when conducting

successfully as a learning activity, at least the

following elements should be taken account: First,

theory and practice should be meaningfully

connected, second learners need to be provided

conceptual and pedagogical tools to enable the

integration of theory and practice when solving

problems, for example, simulated contexts, and third

participating in real-life situations is not solely

sufficient for the development of high-level

expertise. In professional expertise, theoretical-,

practical-, and self-regulative knowledge are closely

integrated (Tynjälä 2008) and the education of

surgical residents shall therefore also be structured

and combine all three.

The current research on continuing education of

health professionals tends to promote research-based

pedagogical self-assessment in professional

development, to help physicians become better

informed about self-assessment and more skilled

monitors of their own practice (Eva and Regehr

2011, Moulton and Epstein 2011). Self-monitoring

is one aspect of self-assessment, a metacognitive

process that is necessary to manage in order to

sustain adequate situational awareness, an important

feature of expert performance (Eva and Regehr

2011, Moulton and Epstein 2011). Moment-to-

moment self-monitoring is an important aspect of

healthcare professionalism that seems to form the

basis of the early recognition of cognitive biases,

technical errors and facilitating self-correction and

self-questioning (Epstein et al. 2008).

Simulators are suggested to be used as training

tools within formal residency curricula, which would

integrate SBT into surgical residents’ other daily

work routines (Kneebone 2003, Van Dongen et al.

2008). Practicing opportunities should be organised

systematically and periodically within longer

ActivityTheoryasaLenstoIdentifyChallengesinSurgicalSkillsTrainingatHospitalWorkEnvironment

457

interval periods in order for the requirements for

expertise development in complex skills like

laparoscopy to be fulfilled (Ericsson 2004). It would

also be important to get the senior surgeons involved

in training, although simulator practise should

always contain tutoring, assessment and corrective

feedback for enhancing learners’ evaluative

reflection processes (Kneebone 2003, Epstein et

al.2008).

Based on the knowledge gathered on former

literature relating surgical skills training as well as

the empirical findings gathered from the surgical

procedures performed by the residents under senior

guidance, the curriculum of laparoscopy skills

learning was launched in 2008 which contained both

instructive sessions with supervisor and independent

training as well as lectures (Silvennoinen 2011).

Simulator training took place in a skill centre at

hospital, where residents could practice with the

simulator when actual patient care allowed. The

support during training was offered through

specialist instructions, feedback and assessment

tasks performed both residents themselves (self-

assessments) and seniors (evaluations/exams). Also

the simulator measurements were available

(performance parameters) for training feedback.

Training alongside real patient treatments was

considered as a connective link from the simulator to

real workplace learning. Also lectures and instructed

self-study was organized to enhance learning

(Silvennoinen 2011). However there emerged

challenges such as time allocation problems which

interfered both residents training and supervisor

surgeon’s guidance and some residents dropped out

the program or didn’t perform adequate amount of

simulator training to achieve the required skill level,

even though training was experienced both

important and useful (Silvennoinen 2011).

4 ACTIVITY THEORY IN THE

CONTEXT OF SURGICAL

LEARNING AT HOSPITAL

Activity theory (AT) offers a theoretical framework

to study both individual and collective activities.

The basic unit of analysis in activity theory is human

activity which ties individual actions in context. An

activity has in particular situation it also means that

it is impossible to make general classification of

what is an activity (Kuutti 1991). It provides an

analytical framework within which to study human

activity in general. An activity system (AS) includes

two types of constituents: core components, such as

subject, object/outcome, and community; and

mediatory components, such as instruments/tools,

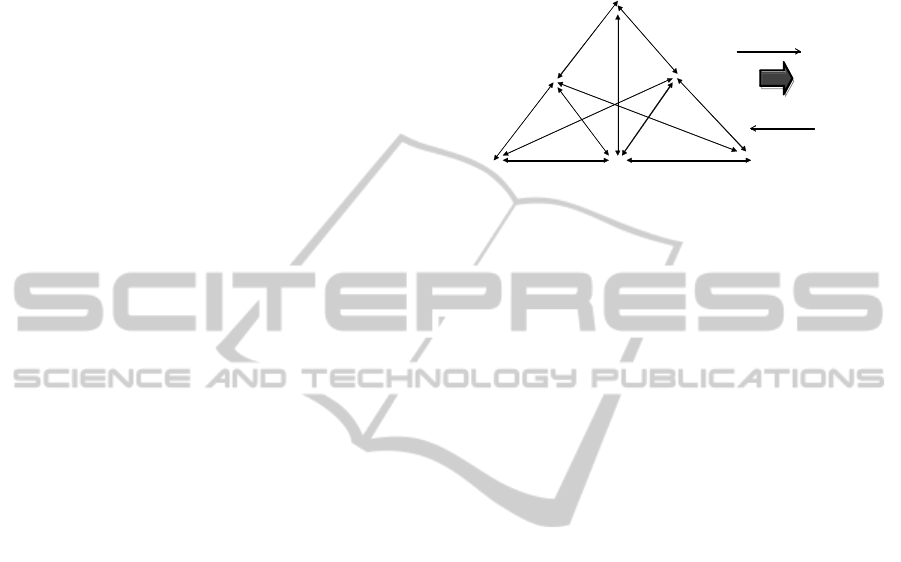

rules, and division of labor (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The structure of a human activity (adapted from

Engeström, 1987, p. 78).

Engeström added the concept of contradiction onto

Vygotsky´s (1978) thinking. Contradictions

constitute a key principle in AT and shape an

activity (Engeström, 2001). Kuutti (1996, p. 34)

describes contradictions as “a misfit within

elements, between them, between different

activities, or between different development phases

of a single activity”. They generate “disturbances

and conflicts, but also innovative attempts to change

the activity” (Engeström, 2001, p. 134).

Contradictions are significant for development

and they exist in the form of resistance to achieving

goals of the intended activity. They also exist as

emerging dilemmas, disturbances, and

discoordinations. In spite of the potential of

contradictions to result in development in an activity

system, the development does not always occur.

Often contradictions may not be easily recognized or

acknowledged, visible, or even openly discussed by

those experiencing them (Engeström 2000 2001). On

the other hand, contradictions that are not discussed

may be embarrassing, or uncomfortable in nature.

They may also be culturally difficult to confront,

such as personal habits, bad behaviour, or an

incompetence of the leader.

An activity is always associated with long-term

purposes and strong motives. All members of the

community share the object (and the motive) of the

activity. Tools mediate between a subject and the

object, which is transformed into the outcome. The

object is seen and manipulated within the limitations

set by the tools. Rules mediate the relationship

between the community and the subject, while the

division of labor mediates the relationship between

the community and the object. Rules cover both

implicit and explicit norms, conventions, and social

Inst

r

uments

Object

Rules

Subject

Communit

y

Division of

l

a

bour

Outcome

Transformation

Motivation

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

458

relations in a community as related to the

transformation process of the object into an

outcome. The responsibilities of the members of the

community are coordinated by some division of

labor (e.g., the division of tasks and roles among

members of the community and the divisions of

power and status), yet guided by rules. These rules

regulate, as well as constrain, their actions and

relationships in the activity system (Engeström

1990, Kuutti, 1996). A weakness of the AT and also

strength to some extend is its generality. The

definition being totally dependent on what the

subject, object etc. is in particular situation it also

means that it is impossible to make general

classification of what is an activity (Kuutti 1991).

To summarize, subjects, who are motivated by

an object, carry out activities. A subject transforms

the object into an outcome. An object may be shared

by a community of people, working together to

achieve a desired outcome. Tools, rules, and a

division of labor mediate the relationship between

the subjects, community, and the object.

Contradictions are a key principle in AT and they

are driving force of change.

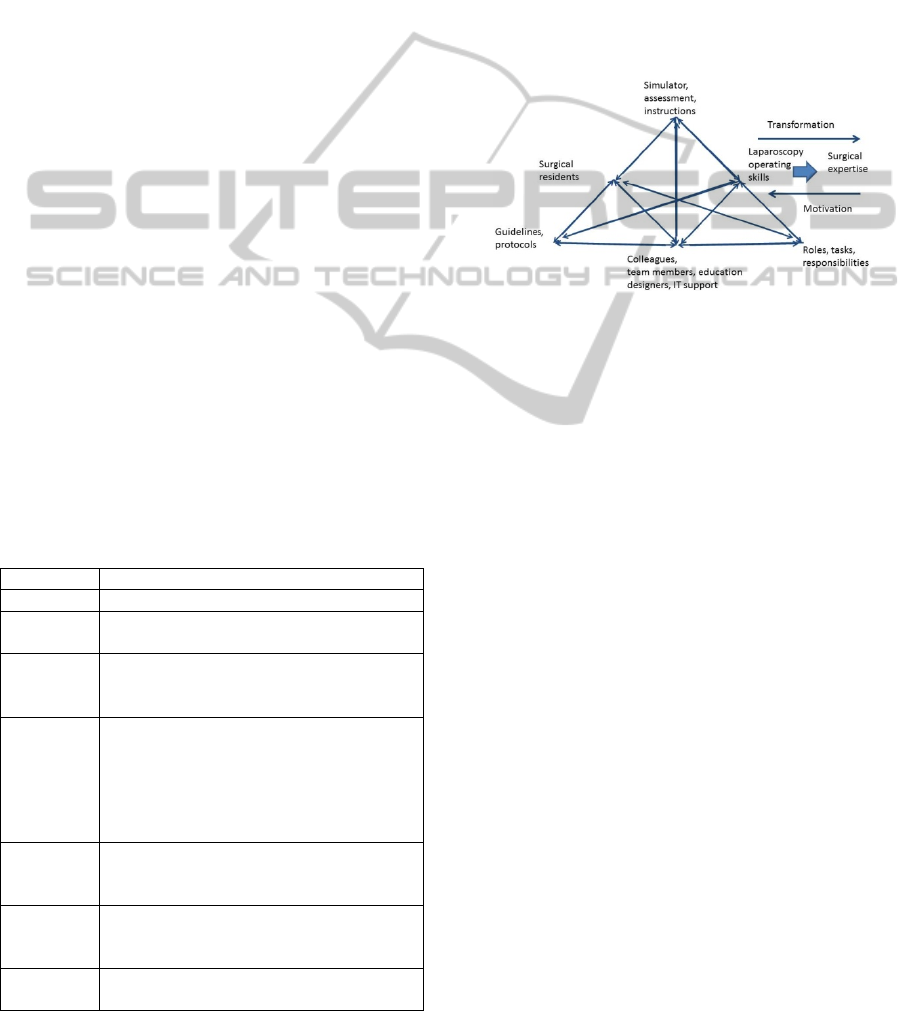

In the depiction of surgical residents training at

hospital as an activity, the resident surgeons are

chosen to be a subject. A subject plays a key role

when analysing other elements of an activity. In this

case we are interested in how the hospital working

culture promotes or restricts workplace learning –

how for example the tools support residents learning

and achieving the learning objectives or how the

Table 1: Surgical residents training at hospital.

Component Description

Subject Resident surgeons

Object To learn skills needed in operating

laparoscopic procedures

Outcome Resident surgeons with adequate

professional skills to perform surgical

operations

Instruments

(tools)

Virtual reality simulator for practicing

p

sychomotor skills, ergonomics, procedures

etc., guidelines and instructions (written,

online videos, lectures, seminars), senior

surgeons guidance during simulator training,

pedagogic methods

Community Surgical residents, senior surgeons, surgical

team members, education designers, IT

support

Division of

labour

Roles, tasks, responsibilities divided among

a community such as teaching, skills

practising, guidance, support

Rules Patient treatment policies guidelines,

treatment protocols

community supports the usage of the tools. From the

residents’ and supervisors’ as well as hospital points

of view, the main object is to produce skilled

professional surgeons for the hospital work to

maintain and further enhance patient safety, working

efficiency and resources. The activity “surgical

residents training at hospital” is presented in the

terms of activity theory (AT) in Table 1.

The instruments (tools) include simulation

environment for practising skills, assessment tools

such as self-assessment forms and instructions for

training and conducting independent learning, senior

guidance sessions, lectures etc. (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Surgical residents training at hospital as an

activity.

The mediating tools in the surgical education context

in hospitals could be seen as enhancing

metacognitive and reflective skills, such as creating

possibilities for supervisor-learner discussions and

self-assessments. For improving workplace learning,

Kyndt et al. (2009) sees as the most crucial

contribution to support the condition of “feedback

and knowledge acquisition”. This means creating

situations for receiving feedback, such as enhancing

teamwork practices, debriefings or peer feedback

possibilities (Kyndt et al. 2009).

5 CHALLENGES IN SURGICAL

TRAINING AT HOSPITAL

WORK

The empirical evidences presented in this chapter are

based on Silvennoinen´s study (2011). The study

was conducted in a Finnish hospital in which

resident training was studied with variable methods,

such as observations, and data was also gathered via

interviews and questionnaires and analysed with

both qualitative and quantitative approaches.

However, in this paper we present several

contradictions in AT system of surgical residents

training applying new simulation-based learning

ActivityTheoryasaLenstoIdentifyChallengesinSurgicalSkillsTrainingatHospitalWorkEnvironment

459

approach at hospital work environment. Many of the

contradictions are in connection to the elements of

expansive workplace learning and emerge when

organisations are not fostering an expansive

workplace learning approach.

The problematic issues or contradictions within

AT system can be listed as the elements affecting to

training program implementation and the realisation

fluency of this new type of workplace learning.

1) Workplace culture, such as hospital’s

recognition and support for employees as

learners can be compromised by the fact that

there is not enough planned time off-the-job for

simulation-based training (SBT). This creates a

contradiction between the Rules and Subject.

2) Second contradiction relates to senior surgeons,

since hospital’s recognition of, and support for

employees as teachers/instructors is sometimes

also compromised by the same fact that they

also have other tasks and not enough planned

time off-the-job for instructors of (SBT) for

facilitating learning and developing their own

competences. This creates a contradiction

between the Division of labour and

Community.

3) Lack of metaskills – (self-assessment is

experienced as difficult task). This

contradiction emerges when Instruments are

not supporting the Subject.

4) Learning requirements; the gap between the

surgical work task demands and existing skills

(too difficult tasks for example relating

psychomotor abilities). This creates another

contradiction between the Rules and

Instruments.

5) Special characteristics /constraints of the

simulation environment; usability and efficacy

problems: realism, interactivity, received

feedback, potential to enhance skill transfer.

This inner contradiction emerges within

Instrument.

Figure 3: Identified contradictions.

Contradictions have several consequences. The

contradiction between Rules and Subject creates

problems with motivation when residents are not

willing to come to practise skills with simulators

after normal working hours. Also the problems of

managing one’s working hours might cause

exhaustion which results in motivation decrease.

6 CONCLUSIONS

From the curriculum design viewpoint, we should be

able to define the activities that surgical residents

need to engage in. The two main tasks taking care of

patients and learning to become specialised

physicians seem sometimes contradictive.

Identifying contradictions within and between these

two different activities - effective learning at

workplace and taking care of patients should

enhance understanding on how the workplace

learning could be enhanced more efficiently.

In this paper we used the concepts from the

activity theory (Engeström 1987, 1999) to identify

contradictions within the surgical residents training

at hospital activity. The following contradictions

were identified: contradiction between the Rules and

Subject, contradiction between the Division of

labour and Community, contradiction between

Instruments and Subject, contradiction between the

Rules and Instruments, and inner contradiction

within Instruments.

There are several studies that support the

findings of this paper. It has been noticed that the

hospital routines and rules are not adequately

supportive of changes within resident education that

has remained unchanged for centuries. The study of

Van de Wiel et al. (2011) is supporting this

argument, which shows that learning opportunities

for expertise development are not utilized optimally

by the young physicians at clinics. The learning is

organized according to physician’s practical

experience and patient care procedures, and

opportunities for enhancing deliberate learning are

not actively sought (Van de Wiel et al. 2011).

In the study of Kyndt et al. (2001) there emerged

several prohibiting reasons for participation in

formal learning activities amongst public healthcare

employees. The residents were discouraged by the

‘required investments’ such as distance, costs, time,

or writing assignments relating to the learning

activity and they also more likely have children, who

might prohibit extra working or training hours

(Kyndt et al. 2011). On the other hand the older

generation, like senior surgeons might have

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

460

attitudinal issues towards learning with new

technology and might even experience that they are

not good at learning new things and “refuse going

back to school (Kyndt et al. 2011).

In a context of education, for example, a

contradiction in teachers’ practices might occur

when a new technology is introduced into their

activity system and clashes with an old element (see

e.g. Engeström 1995, Murphy and Manzanares

2008, and Turner and Turner 2001). The similar

features emerge at the surgical simulator training

while implemented in traditional working culture.

We present recommendations for dealing with

the contradictions that we presented in this paper.

First, the lack of hospital’s recognition and support

for employees as learners and fact that there is not

enough planned time off-the-job for simulation-

based training. The contradiction between the Rules

and Subject can be dealt with careful planning and

implementation of new workplace learning activities

which creates a culture in which better commitment

of the whole organisation and all workers is reached.

The potentiality for workplace learning depends here

on the extent that hospital is designed not only to

produce service of patient care, but to support

workers competency development (Ellström et al.

2008). The success for supporting workplace

learning would therefore require changes to

traditional training culture and whole hospital

organisation. Enhancing open discussions and

enabling high level decisions relating trainees and

trainers division of labor is needed. Better success

would be acquired by investing more human

resources and time allocated for instruction, training

and facilitating.

Second contradiction was the lack of instructors

time allocated to instructing residents since they also

has several other tasks relating patient treatment.

This contradiction between the Division of labour

and Community could be dealt with similar

proposals for action. Lack of metaskills of the

medical residents as well as specialist doctors has

also been found in other research (Silvennoinen

2011) which suggests that educating and practising

self-monitoring and self-assessment is needed.

The contradiction between Rules and

Instruments caused by too high demands in learning

should be solved by offering the residents gradual

progressive tasks with senior support and guidance.

At work the interaction between novices and experts

is very important (Billet 2000) and in surgery this

means that the residents needs to interact with

specialists and work under their guidance, taking

part in the job tasks together – in other words,

participating in the communities of practice (Lave

and Wenger 1991).

The special characteristics/constraints of the

inner contradiction emerging within instruments

need both the technical development and evaluation

of tools used for skills practising, such as surgical

simulators. Supportive actions for training

implementation at hospital environment could also

be co-creative planning and right placement of

training and defining the right training phase within

resident curriculum. Critical evaluation should be

used for guaranteeing continuity and quality

progress of the education design.

REFERENCES

Aggarwal, R., Grantcharov, T., Moorthy, K., Hance, J. and

Darzi, A. 2006. A competency-based virtual reality

training curriculum for the acquisition of laparoscopic

psychomotor skill. The American Journal of Surgery

191(1), 128-133.

Basharina, O. K. 2007. An activity theory perspective on

student-reported contradictions in international tele-

collaboration. Language Learning and Technology,

11(2), 82-103.

Billett, S. (2000). Guided Learning at Work. Journal of

Workplace Learning, 12(7), 272-285.

Bleakley, A. 2011. Learning and Identity Construction in

the Professional World of the Surgeon. In H. Fry and

R. Kneebone (Eds.) Surgical Education: Theorising

an Emerging Domain. Netherlands: Springer, 183-

197.

Britt, L. D., Sachdeva, A. K., Healy, G. B., Whalen, T. V.,

and Blair, P. G. (2009). Resident duty hours in surgery

for ensuring patient safety, providing optimum

resident education and training and promoting resident

well-being: a response from the American College of

Surgeons to the Report of the Institute of Medicine,

“Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision,

and Safety”. Surgery, 146(3), 398-409.

Ellström, E., Ekholm, B. and Ellström, P. 2008. Two

Types of Learning Environment: Enabling and

Constraining a Study of Care Work, Journal of

Workplace Learning, 20(2), 84-97.

Engeström, Y. 1987. Learning by expanding: An activity-

theoretical approach to developmental research.

Helsinki: Orienta-konsultit.

Engeström, Y. 1995. Objects, contradictions and

collaboration in medical cognition: an activity-

theoretical perspective. Artificial Intelligence in

Medicine, 7(5), 395-412.

Engeström, Y. 1999. Expansive Visibilization of Work: an

Activity Theoretic Perspective. Computer Supported

Cooperative Work (CSCW), 8(1-2), 63-93.

Engeström, Y. 2000. Activity theory as a framework for

analyzing and redesigning work. Ergonomics, 43(7),

960-974.

ActivityTheoryasaLenstoIdentifyChallengesinSurgicalSkillsTrainingatHospitalWorkEnvironment

461

Engeström, Y. 2001. Expansive Learning at Work:

towards an Activity Theoretical Reconceptualization.

Journal of Education and Work, 14(1), 133-156.

Epstein, R. M., Siegel, D. J. and Silberman, J. 2008. Self-

monitoring in Clinical Practice: A Challenge for

Medical Educators. Journal of Continuing Education

in the Health Professions, 28(1), 5-13.

Ericsson, K. A. (2004). Deliberate practice and the

acquisition and maintenance of expert performance in

medicine and related domains. Academic medicine,

79(10), S70-S81.

Eva, K. W. and Regehr, G. 2011. Exploring the

Divergence between self-assessment and Self-

monitoring. Advances in Health Sciences Education

16(3), 311-329.

Fry, H. 2011. Educational Ideas and Surgical Education.

In H. Fry and R. Kneebone (Eds.) Surgical Education:

Theorising an Emerging Domain. Springer, 19-36.

Fuller, A., Munro, A. and Rainbird, H. 2004. Workplace

learning in context. Routledge.

Fuller, A. and Unwin, L. 2010. ‘Knowledge workers’ as

the new apprentices: The Influence of Organisational

Autonomy, Goals and Values on the Nurturing of

Expertise. Vocations and Learning, 3(3), 203-222.

Gallagher, A. G. and O'Sullivan, G. C. 2012.

Fundamentals of Surgical Simulation: Principles and

Practice. London: Springer Verlag.

Helle, M. 2000. Disturbances and Contradictions as Tools

for Understanding Work in the Newsroom.

Scandinavian Journal of Information Systems, 12(1),

81-113.

Kneebone, R. (2003). Simulation in Surgical Training:

Educational Issues and Practical Implications. Medical

Education, 37(3), 267-277.

Kuutti, K. 1991. Activity Theory and Its Applications to

Information Systems Research and Development. In

H.-E. Nissen, H. Klein, R. Hirscheim (eds.).

Information Systems Research: Contemporary

Approaches and Emergent Traditions. North Holland:

Elsevier Science Publishers, 529-549.

Kuutti, K. 1996. Activity Theory as a Potential

Framework for Human-computer Interaction

Research. In B. Nardi (ed.) Context and

Consciousness: Activity Theory and Human Computer

Interaction, MIT Press, Cambridge, 17-44.

Kyndt, E., Dochy, F. and Nijs, H. 2009. Learning

Conditions for Non-formal and Informal Workplace

Learning. Journal of Workplace Learning, 21(5), 369-

383.

Latour, B. 1996. On actor-network theory: a few

clarifications. Soziale welt, 369-381.

Lave, J. and Wenger, E. 1991. Situated Learning:

Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge

University Press.

Moulton, C. and Epstein, R. 2011. Self-Monitoring in

Surgical Practice: Slowing Down When You Should.

In H. Fry and R. Kneebone (Eds.) Surgical Education:

Theorising an Emerging Domain. Springer, 169-182.

Murphy, E. and Manzanares, M. A. R. 2008.

Contradictions between the Virtual and Physical High

School Classroom: A Third-generation Activity

Theory Perspective. British Journal of Educational

Technology, 39(6), 1061-1072.

Norman, G., Eva, K., Brooks, L. and Hamstra, S. 2006.

Expertise in Medicine and Surgery. In K. Anders

Ericsson, N. Charness, P. J., Feltovich, R. R. Hoffman

(eds.) The Cambridge Handbook of Expertise and

Expert Performance, 339-354.

Reznick, R. K. 2006. Medical Education: Teaching

Surgical Skills - Changes in the Wind. New England

Journal of Medicine, 355(25), 2664-2669.

Satava, R. M. 2011. Moral and Ethical Issues in

Laparoscopy and Advanced Surgical Technologies. In

Minimally Invasive Surgical Oncology. Springer, 39-

45.

Silvennoinen, M. 2011. Learning Surgical Skills with

Simulator Training: Residents’ Experiences and

Perceptions. In Proceedings of Informing Science and

IT Education Conference (InSITE).

Silvennoinen, M., Helfenstein, S., Ruoranen, M. and

Saariluoma, P. 2012. Learning Basic Surgical Skills

through Simulator Training. Instructional Science,

40(5), 769-783.

Subramonian, K., DeSylva, S., Bishai, P., Thompson, P.

and Muir, G. 2004. Acquiring Surgical Skills: a

Comparative Study of Open versus Laparoscopic

Surgery. European urology, 45(3), 346-351.

Turner, P. and Turner, S. 2001. A Web of Contradictions.

Interacting with Computers, 14(1), 1-14.

Tynjälä, P. 2008. Perspectives into Learning at the

Workplace. Educational Research Review, 3(2), 130-

154.

Van de Wiel M., Van den Bossche P., Janssen, S. and

Jossberger, H. 2011. Exploring Deliberate Practice in

Medicine: How do Physicians Learn in the

Workplace? Advances in Health Sciences Education,

16(1), 81-95.

Van Dongen, K. W., Van der Wal, W. A., Rinkes, I. B.,

Schijven, M. P. and Broeders, I. A. M. J. 2008. Virtual

Reality Training for Endoscopic Surgery: Voluntary or

Obligatory? Surgical Endoscopy, 22(3), 664-667.

Van Veelen, M., Nederlof, E., Goossens, R., Schot, C. and

Jakimowicz, J. 2003. Ergonomic Problems

Encountered by the Medical Team Related to Products

Used for Minimally Invasive Surgery. Surgical

Endoscopy and Other Interventional Techniques,

17(7), 1077-1081.

Vygotsky, L. S. 1978. Mind in Society. The development

of Higher Psychological Processes. Harvard

University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Yule, S. 2008. Debriefing Surgeons on Non-technical

Skills (NOTSS). Cognition, Technology and Work,

10(4), 265-274.

Yule, S. and Paterson-Brown, S. 2012. Surgeons’ non-

technical skills. Surgical clinics of North America

92(1), 37-50.

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

462