Evaluating the Impact of Smart City Initiatives

The Torino Living Lab Experience

Adriano Tanda, Alberto De Marco and Marta Rosso

Department of Management and Production Engineering, Politecnico di Torino, Corso Duca degli Abruzzi 24, Torino, Italy

Keywords: Living Labs, Smart City, Open Innovation.

Abstract: Launched in January 2016 by the city of Turin, the Torino Living Lab initiative has been designed with the

goal of fostering innovation and entrepreneurship and include the citizens in the Smart City innovation

process. Aimed to private organizations and startups, the initiative identified the most promising Smart City

technologies, systems, and applications, and gave them an opportunity to be tested in a real-life environment.

This paper presents a formal methodology for impact assessment and measurement of success of the Torino

Living Lab initiative. A procedure of ex-ante and ex-post measure is established upon review of research

literature on Living Lab approaches. 16 performance indicators are selected and adapted to the characteristics

of the initiative. Finally, some key takeaways resulting from the preliminary investigation are presented.

1 INTRODUCTION

In recent years, the growth of global population is

fueling the debate on what a city can do to limit the

risks and exploit the opportunities brought by

increasing urbanization trends. In this complex

context, the Smart City (SC) paradigm has been

introduced as a multi-disciplinary and multi-objective

concept with the goal of helping policy makers and

public managers face the problems and chase the

opportunities of the modern urban environment. The

complexity of the SC concept makes it difficult to

understand what are the actions that a city must

undertake to become “smart”. In broader terms, a city

can be considered smart when “investments in human

and social capital and traditional (transport) and

modern (ICT) communication infrastructure fuel

sustainable economic growth and a high quality of

life, with a wise management of natural resources,

through participatory governance” (Caragliu, Del Bo

and Nijkamp, 2011). Quality of life, competitiveness

and sustainability are the main pillars upon which a

city must build its strategic SC plan. This has been the

case of the city of Turin, Italy. In 2009, the

municipality adopted the Turin Action Plan for

Energy (TAPE), a plan aimed at reducing by 40% the

city’s CO2 emission by 2020. The TAPE was a

comprehensive sustainability plan, which included

interventions on multiple dimension of the city,

including improving the energetic sustainability of

public and private buildings, reducing emissions by

public transportation, increasing local production of

energy and optimizing the public lighting system

(Città di Torino, 2009).

In 2011 the municipality of Turin decided to expand

the reach of this strategic renovation initiative. The

result was the creation of the Torino Smart City

(TSC) foundation. The strategic vision of the TSC is

to create a city that is sustainable, environmental-

friendly and efficient; a city that improves the quality

of life of its citizens and their participation by

including them in the innovation process (Torino

Smart City, n.d.). By working in close contact with

the industry, start-up companies, public offices and

citizens, the two main challenges of the TSC

foundation has been facing over the years have been:

how to include the citizens in the innovation

processes of private companies, and how to reduce

the bureaucratic burden that an innovative firm faces

when collaborating with public administrations.

To tackle these challenges, in 2015, the TSC

foundation started working on an initiative that aims

to allow private companies and start-ups to interface

their innovation processes directly with the citizens,

and to facilitate the bureaucratic burden that these

companies have to face. The result of this work has

been the Torino Living Lab (TLL) initiative.

This initiative is a new and unexplored concept for

the city of Turin and many others and the city had the

need to develop a formal methodology for

Tanda, A., Marco, A. and Rosso, M.

Evaluating the Impact of Smart City Initiatives - The Torino Living Lab Experience.

DOI: 10.5220/0006346902810286

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems (SMARTGREENS 2017), pages 281-286

ISBN: 978-989-758-241-7

Copyright © 2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

281

measurement and assessment of the success of the

initiative and its impact on the neighborhood.

This paper describes the methodological approach

taken by the city in order to evaluate the TLL

initiative. First, an overview of the TLL initiative is

given, then the methodology for the assessment of the

initiative is presented and some preliminary results

are showed and discussed while the TLL is still

underway.

2 TORINO LIVING LAB

With the TLL initiative, the city of Turin wanted to

identify the most promising technologies, systems,

and applications, in accordance to the objective of the

TSC strategic plan, and give them the opportunity to

be tested in a real-life environment while encouraging

the involvement of the final users in the innovation

process, as it is the main objective of the Living Lab

research approach (Schuurman et al., 2012) (Niitamo

et al., 2006). The area chosen for the

experimentations is the neighborhood called

Campidoglio.

In January 2016, a public call (Città di Torino,

2016) is launched, defining the main objectives of the

initiatives. The call defines the requirements that each

proposal have to fulfill in order to be accepted into the

initiative. A commission evaluates proposals based

on following parameters:

The proposals should not have a direct financial

burden on the municipality;

The objective of the proposals have to be coherent

with the overall objectives of the TSC plan;

The proposals have to be in some way synergic

with other SC solutions implemented by the city;

The proposals have to have an element of

innovation, whether in the technology, the

processes, or the services provided;

The proposals have to be impactful on the

citizens;

The proposals have to be replicable and scalable

to the whole urban environment;

The proposal have to be accompanied by a

preliminary business model in order to guarantee

its economic sustainability;

The proposal have to be technically feasible. With

feasibility is intended the ability of the TSC office

to provide the required facilitations for the start of

the proposed project.

The TSC office, on its side, would help facilitating

bureaucratic matters with other public offices, such as

creating a fast line to secure permits and

authorizations and waiving all the fees and taxes

involved in the use of public spaces. It would also

facilitate communications between the proposing

firms and other private entities that may be necessary

to start the experimentations, such as utilities or

transportation. The TSC office would also guarantee

exposure of each initiatives by using all available

communication channels, such as institutional

websites and social networking, local newsletters and

poster campaigns, flyers and other advertising

material in public offices. Finally, the TSC office

would put considerable efforts to mediate and engage

the neighborhood into the experimentation process.

Each proposal would have the possibility to organize

meetings with the population to present their solution,

and the TSC office itself organizes several events to

present the TLL initiative.

37 proposals were received. Each technology or

service proposed was evaluated by the parameters

discussed previously. Only the proposals that met all

seven criteria were included in the initiative, bringing

the number of projects down to 32. Starting from July

2016 the initiative entered operations, and will be

concluded by December 2017.

3 METHODOLOGY

Schuurman et al. (2012) and Shamsi (2008) describe

the process required in order to set-up a LL, and

identify five main steps:

Contextualization: exploration of the technology

or service under investigation and its

implications;

Selection: identification of potential users or

users’ groups;

Concretization: initial measurement of the

selected users on a series of metrics in order to

understand their characteristics, behaviors, and

perceptions. This has to be performed as a pre-

measurement;

Implementation: kickoff of the operations of the

LL;

Feedbacks: final measurement of the selected

users on the same metrics used in the

Concretization phase. This has to be performed as

a post-measurement at the end of the research.

The development of the TLL initiative followed a

similar structure. First, the TSC office identified the

neighborhood Campidoglio and its population as the

final users of the initiative. After that, the call was

announced and proposals selected.

The methodology for the “Concretization”,

“Implementation” and “Feedbacks” phases were left

to single players, meaning that the TSC office and the

SMARTGREENS 2017 - 6th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

282

city of Turin would not enforce a standardized

methodology for the implementation and evaluation

of the solutions. However, the TSC office needed to

develop its own methodology for evaluating the

initiative as a whole and for assessing its impact on

the population. To this end, the TSC office decided to

measure the citizen’s characteristics, behaviors, and

perceptions before the implementation of the

initiative, with an ex-ante measurement campaign.

Note that these same metrics will be used for same

ex-post measurement, after the TLL initiative will be

concluded, in order to assess any changes produced

by the initiative and to collect feedbacks.

Furthermore, the TSC office wanted to gather

feedbacks and impressions from the providers of the

tested solutions. A similar methodology of ex-ante

and ex-post measurement was developed to

understand the expectations and the objectives of the

firms at the beginning of the initiative and whether

they were able to meet them.

3.1 Impact Measurement on the

Population

The approach chosen for the identification of the

required set of indicators started by a review of the

literature regarding the evaluation and ranking of

SCs. These works, in fact, present comprehensive sets

of metrics and indicators, employed by the authors to

evaluate the “smartness” level of a city. These sets of

indicators can therefore be used as a baseline for the

evaluation of the TLL initiative’s impacts. To this

end, the work of four authors have been reviewed:

Giffinger and Pichler-Milanović (2007), Cohen

(2014), Lazaroiu and Roscia (2012), and Lombardi et

al. (2012).

After the selection of the sources, the first step in

drafting the set of indicators is to discard all the

macro-economic indicators presented by the authors.

That is because the limited temporal and geographical

nature of the initiative implies a negligible impact on

indicators such as the city’s GDP, the employment’s

level or the immigration’s level, making these metrics

not relevant in the assessment of the TLL initiative.

After these considerations, it can also be noticed that

the authors presented their indicators mostly

following the structure presented by Giffinger and

Pichler-Milanović (2007) that identifies 6 main

factors in the “smartness” of a city:

Smart economy;

Smart people;

Smart governance;

Smart mobility;

Smart environment;

Smart living.

The four sets of indicators, already modified by

discarding the indicators for macro-economic factors,

have been joined together, with duplicates eliminated.

This resulted in a list of 42 indicators. The last step

has been to confront each of these indicators with the

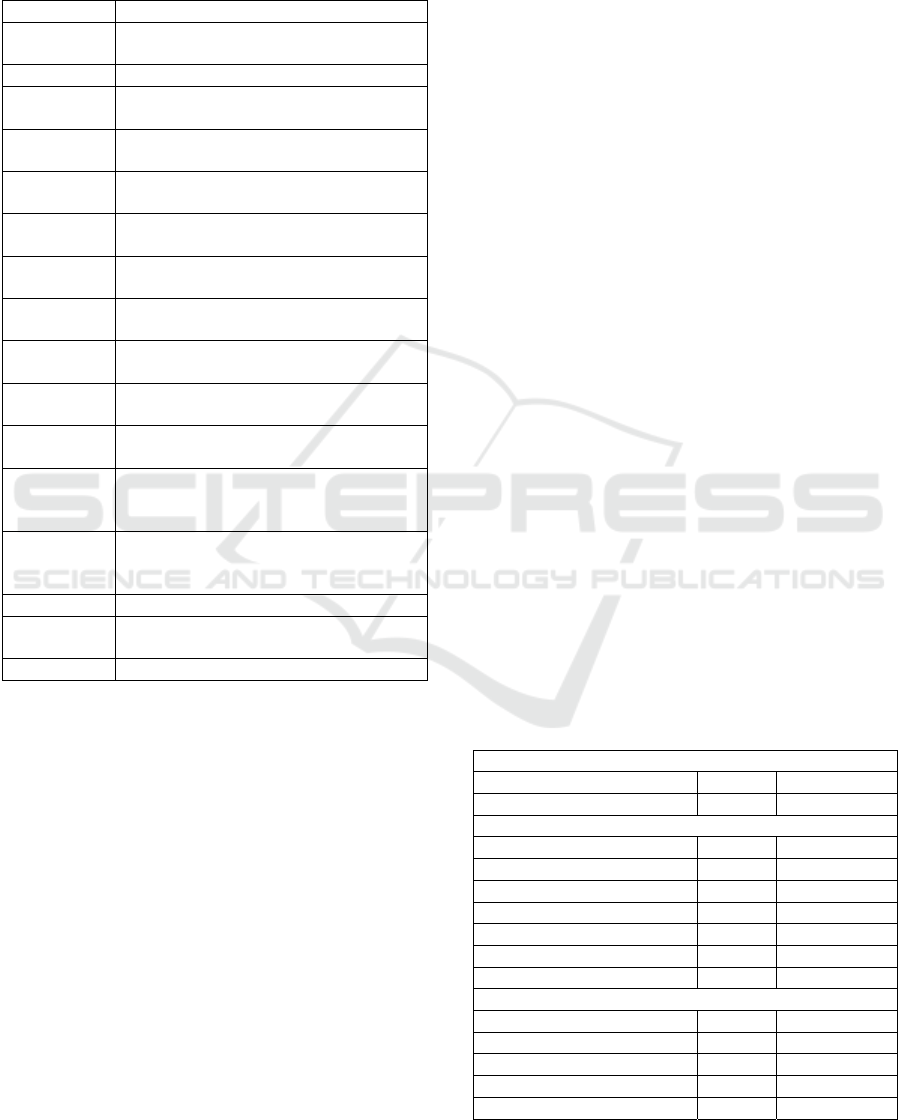

32 selected projects in the TLL initiative. Table 1

shows the classification of the 32 initiatives,

following the SC structure proposed by Giffinger and

Pichler-Milanović (2007).

Table 1: classification of the projects in the TLL initiative.

Domain Number of projects

Economy 3

People 2

Governance 5

Mobility 5

Environment 8

Living 9

This final step allowed eliminating all those

indicators that, while had the potential to impact,

were not influenced by any of the projects in TLL,

bringing the list down to 32 indicators.

However, this list presented some criticalities,

such as the disconnection between the indicators and

the goal of the investigation. While these indicators

are meant to represent a quantitative measure or

statistics, the goal of the investigation is, in fact, to

analyze the characteristics, habits, and behaviors of

the citizens exposed to the TLL initiative. With this

objective in mind, the 32 indicators selected from the

literature have been modified and reworded in a way

that could capture the impressions and opinions of the

citizens on those issues, and assign to those opinions

a quantitative value that could be then used to

evaluate the impacts of the various projects in the

TLL initiative. The final shortlist of 16 indicators is

presented in Table 2.

A survey was the natural choice for conducting

this kind of investigation and assess the values of the

indicators presented in Table 2. The survey submitted

both on line (through the aid of local associations) and

face-to-face during neighborhood meetings, is

structured as follows. The first question set gathers

the demographic profile of the respondents (age,

gender, profession). Then, a question is asked on

whether the interviewees are generally aware of the

TLL initiative and, if yes, which of the 32 projects, if

any, they know. Finally, 15 questions are asked to

understand and measure the perception, behaviors,

and habits of the citizens on the set of indicators given

in Table 2. These perceptions are quantified with a 1

to 5 point Likert scale, with 1 representing a strong

Evaluating the Impact of Smart City Initiatives - The Torino Living Lab Experience

283

disagreement or a minimum, and 5 representing a

strong agreement or a maximum.

Table 2: list of indicators used for the assessment of the

impacts of the TLL initiative.

Domain Indicator

Economy Components of domestic material

consumption

People Civic engagement activities

Governance Usage and perception of applications

based on open data

Usage and perception of institutional

digital services

Mobility Frequency of use and perception on bikes

and/or bike-sharing

Frequency of use and perception on car-

sharing and/or car-pooling

Frequency of use and perception on public

transportation

Assessment on the extensiveness of efforts

to increase the use of cleaner transport

Environment Perception on the total residential energy

consumption

Perception on particulate matter emission

and air quality

Individual effort in protecting nature and

the environment

Assessment on the extent to which citizens

may participate in environmental decision

making

Assessment on the engagement in

environmental and sustainability-oriented

activities

Living Perception on public safety

Participation to cultural initiatives and

events

Use of public and green spaces

As already stated, this measurement needs to be

performed twice in order to gather an ex-ante and an

ex-post measurement, which will allow determining

the impact of the initiative. The first survey,

representing the ex-ante measurement, has been

submitted to the population between the period of

May and July 2016, right before the start of the

projects, and received 71 responses. The ex-post

measure will be done at the end of the TLL initiative,

approximately December 2017 and January 2018. To

guarantee consistency between the two

investigations, the 71 respondents gave their contact

information and agreed to be contacted again to

participate in the ex-post measurement.

3.2 Measure of Impacts on the Firms

The TSC office had also the need to assess the success

on the TLL initiative from the point of view of the

technology and service providers and have a clearer

picture on the expectations and objectives of the firms

when starting the tests on their projects, and whether

these objectives were reached by the end of the

initiative. A similar methodology of ex-ante and ex-

post investigations was developed. The investigation

tool chosen has been semi structured interviews with

each firm, where three questions were asked:

What are your objectives in participating in the

TLL initiative?

How do you plan to evaluate your participation in

the TLL initiative?

Do you have a set of indicators, either qualitative

or quantitative that you plan to measure?

The 32 interviews, with a duration between 15 and

30 minutes have been recorded and some takeaways

can be extracted. At the end of the initiative a second

set of interview will be performed to ascertain

whether the objectives were reached and how did they

evaluate their participation in the TLL initiative.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

As discussed earlier, the methodology for assessing

the impacts of the TLL initiative requires two sets of

measures. Nevertheless, it is possible to gather some

interesting insights by the preliminary analysis of the

ex-ante measurement.

4.1 Survey

The demographic distribution of the survey’s

respondents, by gender, age and profession is

presented in Table 3.

Table 3: demographic mark-up of the survey’s respondents.

Gender

Female 32 45%

Male 39 55%

Age

Less than 18 0 0%

18 - 25 7 10%

26 - 35 12 17%

36 - 45 19 27%

46 - 55 11 15%

56 - 65 11 15%

More than 65 11 15%

Profession

Employee 24 34%

Self-employed/entrepreneur 8 11%

Student 7 10%

Retired 11 34%

Other/unemployed 21 30%

SMARTGREENS 2017 - 6th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

284

The analysis of the ex-ante survey gives an initial

picture on the characteristics, habits, and behaviours

of the citizens of the neighbourhood Campidoglio.

For each question, the degree of agreement was

computed as the percentage of positive votes (4 or 5)

over the total and these results are reported relative to

the measure indicators presented in Table 2:

Economy: the buying choices are dictated first by

the quality of the product (77%), then by the cost

(55%) and lastly by the place of origin (44%).

People: the citizens are not typically engaged into

civic activities (15%).

Governance: most of the digital services and

applications used by citizens are related to

transportation and mobility (42%) and civic activities

(48%), but in general the frequency of use is quite low

(14%). The usage of these applications is, however,

extremely passive, and lacks user engagement as a

content co-generator. Considerations about the

usefulness of these services and ease of use is also low

(respectively 24% and 28%).

Mobility: from the survey’s results, the preferred

mean of transportation is public transportation (49%)

followed by car (24%), bike (23%) and, lastly,

alternative means of transportation such as bike or

care-sharing (20%). Necessity is the main factor in

the choice of transportation (68%), followed by

speed, travel distance (63%), and cost (49%). The

environmental impact of the vehicle is considered as

less important (45%).

Environment: the citizens do not consider

themselves particularly informed regarding the level

of air pollution (14%) and their energy consumption

(34%). Meanwhile they consider themselves

relatively informed on the correct practices to reduce

their energy and environmental impact (42% and 45%

respectively). They are also practicing and

encouraging environmental friendly and sustainable

behaviors (66% and 58% respectively), and they try

to preserve the public green spaces (54%). On the

other hand, there is a lack of participation in civic

activities aimed to environmental protection (15%).

Living: the citizens of Campidoglio feel

themselves relatively safe in their neighborhood

(42%). The usage of public spaces is also relatively

high (46%). Engagement in cultural and social

activities is, again, scarce (20% for both).

In general, it can be noticed a lack of engagement

of the citizens in civic activities and initiatives,

regardless of the topic. The use of digital services and

applications is also considerably low. The awareness

on environmental matters is mixed. While citizens

feel informed on the behaviors to take to be more

environmental friendly, they do not feel informed on

the actual level of pollution.

4.2 Interviews

The first question of the interview asked about the

objective of the project and the participation to the

TLL initiative. While each firm had its own objective,

it is possible to draw some similarities. Between the

32 firms, 4 are participating to the TLL primarily to

test the technical feasibility of their solution. The

primary goal will be to gather valuable insights from

the final users in an early stage of development. Other

4 firms are presenting a relatively mature service or

technology and are using the participation in the TLL

initiative as a way to test on a limited scale the

economic sustainability of the proposed business

model. Furthermore, 15 firms are presenting a

solution that is already at a commercial phase of

deployment and their participation’s goal is creating

demand for the product or tested service, while

gathering user’s feedbacks and opinions for some

possible changes or modifications. The remaining 10

projects present multiple objectives and different

maturity, which makes it difficult to include them in

a single category. Out of these projects, 5 neither have

or plan to have a commercial market application and

are more focused on knowledge sharing,

dissemination, or plan to achieve academic

recognition.

Finally, the interviews also gave insights on the

planned final users of the projects. The first

consideration that can be done is that most of the

projects tested have multiple final users, whether the

citizens, other businesses or the public

administration. The public administration, find itself

with the double role of enabler of the TLL and of the

final users of, specifically, 16 projects. Furthermore,

15 projects have the citizens as their primary target

market, and 21 have other businesses.

5 CONCLUSIONS

One of the challenges that the public administration

has to face in designing a complex and wide-breath

initiative, such as the TLL, is the development of a

control mechanism able to capture the impact of the

initiative on the citizens and to assess its success.

From a the point of view of the literature on the LL

research approach, the most appropriate way to

develop a LL measurement process is to collect the

user’s impressions, habits, and behaviors before the

start of the initiative, in the so-called Concretization

Evaluating the Impact of Smart City Initiatives - The Torino Living Lab Experience

285

phase, and then compare them with those collected

after the end of the testing, in the Feedback phase

(Schuurman et al. 2012) (Shamsi, 2008). The first

step in the application of this methodology has been

the identification of a set of indicators able to capture

the citizen’s habits, behaviors, and impressions. This

process started from a review on the literature

regarding the methodologies for the ranking of SCs.

The comprehensive sets of indicators presented in

these works have been used as a starting point in

designing a set of indicators able to capture the

impacts of the SC innovations tested in the TLL

initiative. However, these sets of indicators required

several further modifications:

Elimination of macro-economic indicators (GDP,

employment, etc.);

Harmonization of the four selected sets into a

single shortlist;

Eliminations of all the indicators of dimensions

not impacted by any project participating in the

initiative;

Modifications of more quantitative indicators to

capture the qualitative nature of the citizen’s

opinions.

The result of these steps was a final shortlist of 16

indicators. This bottom-up approach for identification

of the assessment indicators can be applied with

minimal effort by public administrations in the

context of a LL initiative aimed to test innovative SC

solutions.

Between May and July 2016, the first ex-ante

investigation has been completed through submission

of a survey to a sample of 71 citizens. While these

results are still incomplete and the ex-post measure

will be necessary to understand the entity of the

impacts of the initiative, it is still possible to gather

some interesting preliminary insights. The results

show a severe lack of engagement of the population

in civic activities and most of the interviewed

population reports a minimal use of digital services

offered by the city. Moreover, while there is a general

awareness on environmental issues, the population

reports a lack of information on the level of pollution.

Finally, semi-structured interviews with the

organizations participating into the initiative showed

a heterogeneity in both the maturity of the projects

and on the user targets, from the citizens, to other

businesses, to the public administration.

The next step in the research will be the ex-post

investigation, by the end of the initiative. This will

allow to assess the impacts that TLL had on the habits

and opinions of the population, and to evaluate the

success of the initiative from the point of view of the

organizations involved.

REFERENCES

Caragliu, A., Del Bo, C. and Nijkamp, P., 2011. Smart cities

in Europe. Journal of Urban Technology, vol. 18, no 2,

pp. 65-82.

Città di Torino, 2009. Piano d’azione per l’Energia

Sostenibile. Available from: http://

www.comune.torino.it/ambiente/bm~doc/tape-2.pdf

[01 December 2016].

Città di Torino, 2016. Avviso pubblico per la ricerca di

soggetti interessati alla promozione, lo sviluppo, il

testing e la sperimentazione di iniziative e soluzioni

tecnologiche innovative in ambito "Smart City"

sull’area del quartiere campidoglio. Available from:

http://torinolivinglab.it/wp-

content/uploads/2016/01/Campidoglio_Avviso_torino-

_25-01-2016_Def.pdf [08 March 2016].

Cohen Boyd, 2014. Smart City Index Master Indicators

Survey. Available from: http://smartcitiescouncil.com/

resources/smart-city-index-master-indicators-survey

[03 Marchr 3016].

Giffinger, R. and Pichler-Milanović, N., 2007. Smart cities:

Ranking of European medium-sized cities. Centre of

Regional Science, Vienna University of Technology.

Lazaroiu, G.C. and Roscia, M., 2012. Definition

methodology for the smart cities model. Energy, vol.

47, no. 1, pp. 326-332.

Niitamo, V.P., Kulkki, S., Eriksson, M. and Hribernik,

K.A., 2006. State-of-the-art and good practice in the

field of living labs. In International Technology

Management Conference. IEEE pp. 1-8.

Shamsi, T.A., 2008. Living Labs: good practices in Europe.

European Living Labs–a new approach for human

centric regional innovation, pp.15-30.

Schuurman, D., Lievens, B., De Marez, L. and Ballon, P.,

2012. Towards optimal user involvement in innovation

processes: A panel-centered Living Lab-approach. In

Proceedings of PICMET'12: Technology Management

for Emerging Technologies. IEEE, pp. 2046-2054.

Torino Living Lab, n.d. Torino Living Lab. Available from:

http://torinolivinglab.it [03 December 3016].

Torino Smart City, n.d. La vision. Available from:

http://www.torinosmartcity.it/torino-smart-city/ [03

December 2016].

SMARTGREENS 2017 - 6th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

286