How to Promote Informal Learning in the Workplace?

The Need for Incremental Design Methods

Carine Touré

1,3

, Christine Michel

1

and Jean-Charles Marty

2

1

INSA de Lyon, Univ. Lyon, CNRS, LIRIS, UMR 5205, F-69621 Villeurbanne, France,

2

Université de Savoie Mont-Blanc, CNRS, LIRIS, UMR 5205, F-69621 Villeurbanne, France,

3

Société du Canal de Provence, Le Tolonet, France

Keywords: Lifelong Learning, Informal Learning, Knowledge-sharing Tools, Enterprise Social Media, User-centered

Design, Adult Learner.

Abstract: Informal Learning in the Workplace (ILW) is ensured by the everyday work activities in which workers are

engaged. It accounts for over 75 per cent of learning in the workplace. Enterprise Social Media (ESM) are

increasingly used as informal learning environments. According to the results of an implementation we have

conducted in real context, we show that ESM are appropriate to promote ILW. Indeed, social features are

adapted to stimulate use behaviors and support learning, particularly meta-cognitive aspects. Three

adaptations must nevertheless be carried out: (1) Base the design on a precise and relatively exhaustive

informational corpus and contextualize the access in the form of community of practice structured according

to collaborative spaces; (2) Add indicators of judgment on the operational quality of information and the

informational capital built, and (3) Define forms of moderation and control consistent with the hierarchical

structures of the company. Our analysis also showed that an incremental and iterative approach of user-

centered design had to be implemented to define how to adapt the design and to accompany change.

1 INTRODUCTION

Lifelong learning is an approach to education that has

been addressed since the 1970s to provide the skills

and knowledge needed to succeed in a rapidly

changing world (Sharples, 2000). It includes formal,

non-formal and informal learning (Commission of the

European Communities, 2000). Unlike informal

learning, formal and non-formal learning are

structured with tools or training sequence. The latter

occurs during daily experiences, while working or

interacting with other people. It is characterized by

the merger of learning with the everyday work

activities in which workers are engaged (Longmore,

2011) and is motivated by personal needs. Informal

learning is of central importance for enterprise since

it accounts for over 75 per cent of learning in the

workplace (Bancheva and Ivanova, 2015). It is the

most important way to acquire and develop skills

required in professional contexts.

The Knowledge Management (KM) research field

promotes the management and maintenance of

knowledge sharing in the workplace. Three

generations of technologies were privileged for

informal learning (Ackerman et al, 2013; Hahn and

Subramani, 1999). Two main strategies can be

identified to manage knowledge: valuation of

informational capital and valuation of human capital

with collaboration (Ackerman et al, 2013; Wenger,

2000).

The first generation considers that workers can

continuously learn and be able identify solutions to

problems they can meet during working activities.

They have to look for information on processes and

know-how related to their activity. To support them,

enterprises produce relatively exhaustive information

corpuses on working activity and make them

accessible. Despite their exhaustiveness, these

knowledge databases remained most of the time

unused because they were maladjusted to

collaborators needs and characteristics; particularly

regarding information access and training (Hager,

2004; Graesser, 2009). Moreover, access tools to this

information are not dedicated to learning process.

Indeed, Graesser (2009) recommended to privilege

training objectives based on auto-regulation and

meta-cognition ; and by this way help learners to

“learn how to learn’. He describes (Graesser, 2011)

220

Touré, C., Michel, C. and Marty, J-C.

How to Promote Informal Learning in the Workplace? - The Need for Incremental Design Methods.

DOI: 10.5220/0006355502200229

In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2017) - Volume 2, pages 220-229

ISBN: 978-989-758-240-0

Copyright © 2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

various principles based on fun, feedback or control

to support learning.

The second generation focus was on expertise

sharing and identification of experts able to provide

useful information to collaborators. Communities of

practice (CoP) were commonly adopted by

enterprises to help practitioners express, share and

exploit their knowledge (Pettenati and Ranieri, 2006;

Wenger, 2000). Direct interaction between peers was

recognized to facilitate knowledge transfer and

improve information quality (Wang, 2010). However,

the lack of information completeness, accuracy in

identification and recommendation of expert, privacy

protection and control revealed some limits

(Ackerman et al, 2013). CoPs have remained hardly

ever used.

The third generation combines principles of both

first and second generations. It is characterized by

collaborative information spaces merging

information repositories, communication and

collaboration processes. Many enterprises chose to

implement enterprise social media (ESM) to improve

organizational performance, especially in the

knowledge sharing context (Ellison, Gibbs and

Weber, 2015). They integrate management of

working activity, knowledge management strategies

and social aspects promoting interactivity between

peers (Dennerlein et al, 2015; Leonardi, Huysman

and Steinfield, 2013; Riemer and Scifleet, 2012).

ESM foster informational and social capital

valuation; they are particularly well adapted to find

and interact with collaborators, receive and seek for

help (Ackerman et al, 2013). They are also easier to

manipulate, more attractive and interactive than

traditional collaborative environments. They fulfill

users’ needs for usefulness and gratification (Ersoy

and Güneyli, 2016). Indeed, they allow the

recognition of each one in the contributions made and

permit social connections materialized by simple

actions as following a post or as commenting.

Nevertheless, the free access to information,

contribution and cooperation features has opened the

door to misuse leading to a lack of efficiency in the

exploitation of information resources or a feeling of

harassment (Turban, Bolloju and Liang, 2011).

Our objective is to study to what extent ESM are

actually adequate tools to implement informal

learning strategies. More specifically, we will study

what social features are the most effective to match

learning objectives stated by Graesser and how to

make them coherent with the objectives and practices

of the organization and collaborators. The long-term

objective is to favor a sustainable use. To answer

these questions, we present in the next section ESM

characteristics and how they can significantly support

informal learning in the workplace. This helped us

identify various design propositions. We

implemented these propositions in a real context to

evaluate their accuracy and refine them. This study is

presented in the third section of the paper.

2 USING ESM FOR INFORMAL

LEARNING

2.1 Pros

ESM features promote construction and identification

of relevant information. Comments within social

media are an emblematic form of expression and a

communication tool for users to effectively judge the

quality of information and easily participate to

content construction. Indeed, information captured

within informal learning tools evolves and may

become rapidly outdated. Comments have the

advantage that workers can communicate and

participate online to the construction of the

knowledge corpus (Kaplan and Haenlein, 2010), they

reduce the risk of forgetting or losing practice.

Appreciations left by users provide us with an

additional way to evaluate information quality and to

promote information submission. They can be

formalized as in some wikis where content posted can

be qualified with completeness and readability

indicators. These indicators allow collaborators to

form their opinion on the content and better

understand how they can participate to its refinement.

This feedback helps authors to be aware of the

usefulness of their publications (Kietzmann,

Hermkens andMcCarthy, 2011) and helps to build

their reputation. Moreover, wikis frequently use these

features to support collaborative innovation, problem

resolution and more generally help organizations

improve their business processes (Turban, Bolloju

and Liang, 2011).

ESM provide visibility and persistence of several

communicative actions like download, content

publication, identification of what others do, status

update, profile creation (possibilities to highlight

particular aspects of themselves), connecting with or

following people (Leonardi, Huysman and Steinfield,

2013; Stocker and Müller, 2013). They expand (and

precise) the range of people, networks and contexts

from which people can learn across the organization.

Making communicative activities visible also

allows self-regulation. Notifications, number of

appreciations, new submissions, etc. help identify

How to Promote Informal Learning in the Workplace? - The Need for Incremental Design Methods

221

what and how others do, evaluate what one’s do and

adjust one’s own behavior. It promotes meta-

cognition and meta-knowledge (learn how to learn)

(Schön, 2000). This awareness thus becomes an

intrinsic motivator to construct one’s own numerical

identity through indicators (Zhao, Salehi and

Naranjit, 2013). Being involved in a group helps

collaborators develop meta-social knowledge and

facilitates their ability to collaborate and coordinate

(Janssen, Erkens and Kirschner, 2011), particularly

within CoPs.

2.2 Cons

Janssen et al (2011) identifies two groups of risks

linked to the problems of acceptance and to the use of

ESM and quality of content published by

collaborators.

The acceptance and the ability to use play a basic

role on the initial and continuous use of technologies.

The process of acceptance begins with the

construction of initial beliefs towards the information

system. They are generated by external stimuli such

as system quality, service quality, knowledge quality

or information quality (DeLone and McLean, 2003;

Jennex and Olfman, 2006; Kulkarni, Ravindran and

Freeze, 2007; Venkatesh et al, 2003). These beliefs

are moderated by personal factors like age, previous

experience or service quality (Venkatesh, Thong and

Xu, 2012). They also influence the ease of use of the

system. Indeed, an efficient use may require high

levels of literacy and technical proficiency in seeking

for information, evaluating its usefulness and

truthfulness or connecting with remote people or

computers (Benson, Johnson and Kuchinke, 2002;

Turban, Bolloju and Liang, 2011). Contextual

characteristics of collaborators are most of the time

not considered during the design process (Longmore,

2011). To develop meta-social skills and improve

communication as proposed by Graesser (2011),

users need clear learning objectives and awareness on

peers feedback and information quality. They also

need recognition of what they do (improvement of

professional reputation, acknowledgement from

community, being informed that their actions are

appreciated by others) (Wang and Noe, 2010).

Moreover, policies and structure of governance (i.e.

monitoring, control or filtering of system accesses)

have to be established as well as management

campaign of training) (Turban, Bolloju and Liang,

2011). These solutions are money and time

consuming, especially for limited IT budgets and

companies that seek rapid and simple collaborative

solutions. After this initial cycle of use, the user

acquires an experience that helps him to construct

new beliefs and experience confirming or refuting the

previous ones ; this impacts his attitude towards the

system (satisfaction or dissatisfaction) and his

intention to use the system (Bhattacherjee, 2011;

Bhattacherjee, Limayem and Cheung, 2012).

The second group of risks concerns the validity

and quality of information created and published.

Despite the fact that published content is most the

time not anonymous within ESM, it can be useless for

informal learning since information is often poorly

detailed and proofread, particularly if knowledge

objects manipulated are of technical nature. Within

social media, posts are very often brief and people

give generic information without giving details. This

may be suitable for updates, but not for the

construction of the core information corpus.

Moreover, people may engage in informal behavior

when using social media. Activities like using

improper language, publishing information that is

confidential, using incomplete information or using

ratings or comments to harass colleagues may be

common. The ability to discern the quality of the

accessible information is mostly incumbent upon

users and they have little control in these

environments, which is one principle of social media

(Bhattacherjee, 2011; Turban, Bolloju and Liang,

2011). These risks may negatively affect the social

and learning environment and call into question the

expected learning processes.

2.3 Summary and Proposition

ESM appear to be suitable to support informal

learning in the workplace. They supply functionalities

that promote and facilitate collaboration, knowledge

sharing, user motivation and visibility, and

information persistence. They also propose reflexive

indicators that facilitate the analysis and coordination

of collective activities, social connection and

learning. These characteristics position workers and

their needs at the heart of the learning environment,

making ESM appropriate tools to support informal

learning in the workplace. However, their use may be

inefficient due to the profile of workers, who are adult

learners and need to be aware of the value of their

participation in the learning group: they seek concrete

personal and professional feedback, usefulness and

gratification. Moreover, the quality of information

published may be problematic regarding learning

strategies.

To reduce the risks related to information quality,

we believe that it is important to base the learning

environment on a precise and exhaustive information

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

222

corpus. This informational architecture which is most

of the time already formalized into information

systems can then be enriched with collaborative

characteristics. Literature review showed that

indexation and structuration of information have to be

reviewed to facilitate contextual access. A search

engine and indexation tags are fundamental elements

to guaranty a transversal access to information.

Activity’s contextual aspect such as the one

proposed by CoPs can be reproduced with structured

wikis according to enterprise’s working communities.

Various elements have to be considered to guaranty

quality and trustworthiness of published content; and

also facilitate contribution: select useful information,

organize it according to specific template files, and

organize validation according to hierarchical

decision-making structures of the community.

As regards to learning support, literature review

showed three additional characteristics of ESM to

promote users’ engagement: visibility and reflexivity.

Comments and appreciations (e.g. “Likes”) can be

considered as tools for expression and

communication, allowing collaborators to provide

feedback and participate to construction of contents.

These features allow them to be involved into the co-

construction of knowledge and maintain an updated

available information which is important for the

quality of learning processes. Awareness indicators

like notifications (of new submissions, who and

when, number of comments) promote the

construction of meta-cognitive skills for self-

regulation and stimulate participation. Indicators of

information quality facilitate identification of useful

content and collaboration by a critical analysis of

items to be added to update and improve contents.

Finally, to minimize risks of misuse of the

environment, we propose to use a user-centered,

incremental and iterative design methodology. This

methodology allows to identify characteristics and

preferences of users and to design a contextually

adapted environment. The incremental and iterative

nature of the approach also makes it possible to

accompany the change associated with the

introduction of a new information system and thus to

positively influence its acceptance and its initial and

continuous use. Indeed, since informal learning is

inherent in the employee’s will and not stimulated by

accompanying strategies, this characteristic appears

fundamental. Analysis of core acceptance of

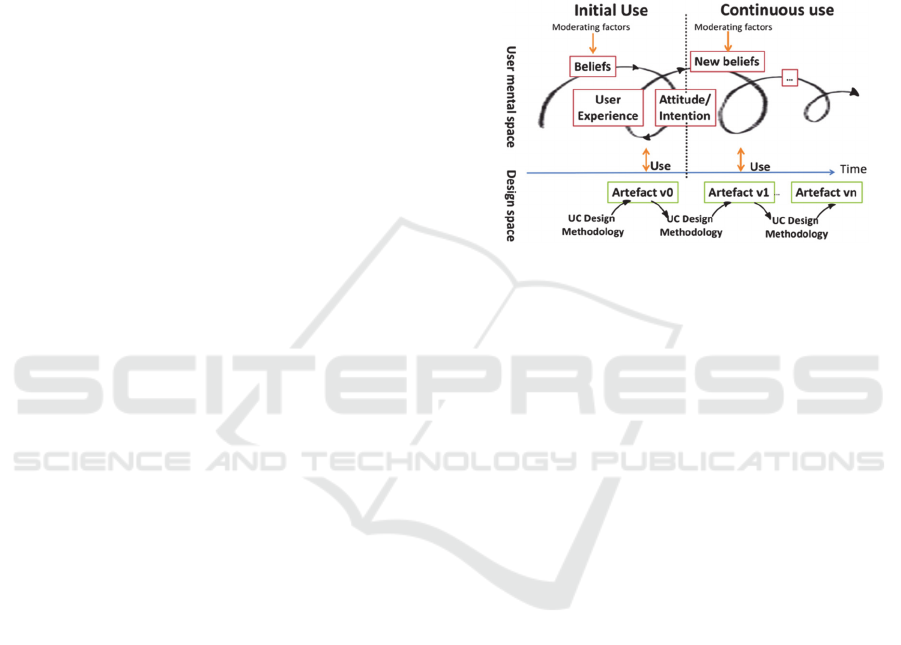

technology models in the workplace showed that the

acceptance model can be represented with a spiral

(see Figure 1) structured with conditions of use.

Every loop builds an artifact increasingly adapted to

users' needs and behavior. We posit that the

sustainability of our process can be effectively

ensured by providing users with an artifact matching

their profile and needs at each stage of this cycle.

We implemented our methodology in a real

context. The objective was to identify the most

adapted ESM features that promote informal learning,

to assess the feasibility of the methodology and to

identify a structuring order of the various items which

have to be considered at each stage. We present the

results of this experimentation in the next section.

Figure 1: Incremental and iterative design of information

systems for informal learning.

3 IMPLEMENTATION

3.1 Context and Constitution of the

Working Group

The Société du Canal de Provence (SCP) is located

in the south of France and specializes in services

related to the treatment and distribution of water for

companies, farmers and communities. The

intervention territory is divided into ten geographic

areas called Operating Centres (OC). Each OC

corresponds to a community of practice in which we

find three positions: the Operator (O), the

Coordinator Technician (CT) (an operator who also

has the role of manager of the community), and the

Support and Customer Relationship Technician

(SCRT). They are the responsible people for the

maintenance of hydraulic infrastructures (canals,

pumping stations, water purification stations, etc.).

The operators need a wealth of knowledge about their

work: there is a lot of (sometimes dynamic)

information to learn and knowledge sharing is

especially important.

To assist them, SCP produced in 1996 a

knowledge book about the processes and hydraulics

infrastructures. This information was accessible

through a tool named ALEX (Aide à L’EXploitation).

It gathered information from returns on experience

How to Promote Informal Learning in the Workplace? - The Need for Incremental Design Methods

223

sheets developed in HTML format, and stored it

within a directory on a dedicated server in each OC.

Throughout its twenty years of existence, it was

hardly ever used despite the fact that collaborators

agreed with the learning environment principle. One

main reason was because accessibility to information

was not adapted. ALEX was a typical sample of

traditional KM strategies based on knowledge books

and produced in the 1990’s. It is an appropriate

context to work on means capable of supporting

lifelong learning.

Four OCs were selected by the responsible person

for the project to act as pilot OCs. Eleven employees

coming from those OCs were invited to freely

participate in the working group. They were chosen

according to their experience and different positions,

thus being representative of various trades within the

company, and according to their use of the previous

version of the knowledge book. The focus groups

were moderated by ourselves and by a member of the

working group (a board member, responsible for the

ALEX project). We count in total twelve sessions

conducted on a two years period. The first year

consisted in formalizing the basic users’ needs. Six

meetings, separated by about two to three weeks,

allowed us to propose a solution increasingly refined

until a last version fully usable in the work context.

The platform was made available to users for three

months. At the end of this first year, a debriefing

meeting was held on the eligibility of the proposed

solution and a new analysis and design cycle was

initiated. It took seven months and six working

sessions.

3.2 The First Design Cycle

Results of the first cycle are presented more in detail

in (Touré et al, 2015). In summary, this stage showed

that the main requirement that emerged from the

meetings was to propose easier ways to search for,

submit and access knowledge (see Figure 2 zone

1,5,7) organized in collaborative CoPs according to

the different OCs. The discussions allowed us to

identify the general structure of navigation and

organization of the information of the website and the

methods of structuring knowledge, in particular

eleven different structures of data sheets. A work of

harmonization of the architecture of the various IS

was carried out to integrate Alex with the other IS and

with the intranet of the company. The objective was

to facilitate the navigation between the different tools

and thus their accessibility from every workstation

and in mobility. A simplified numerical space

reproducing a word processor office suite and various

document templates were designed. Four user roles

were proposed to control submissions and guaranty

information quality – the reader, the contributor, the

validator and the manager. The working group was in

charge of attributing the different roles. For example,

the validator roles were attributed to CTs who are

responsible for each OC while the manager roles was

attributed to ALEX project responsible person.

After a three months use, an evaluation was

conducted and showed that this new version of ALEX

match the basic users’ expectations but lacked

attractive items to guaranty a long-term usage (Touré

et al, 2015). The second design cycle allowed us to

work on these elements.

3.3 The Second Design Cycle

Discussions were about design of items for

stimulation, control and monitoring of activity. They

revealed two emerging groups of needs for

readers/contributors and for validators/managers. The

first ones were sensitive to the addition of social

features and activity indicators (comments, ratings,

notifications…) while the latter expressed

expectations about monitoring activity via an activity

dashboard. We present in the following subsection

results related to social features, since the dashboard

is still being developed currently.

3.3.1 Comments and Appreciations

Discussions on comments and appreciation were

based on mockups presenting interactions that mimic

what is commonly done in Web 2.0 knowledge

construction tools like blogs or wikis: comments and

“Likes” counting number of positive appreciations.

All the participants agreed with the idea of using

comments as they are simpler means of

communication than emails. They also make the

sheets interactive, as they can be seen as an

‘annotation tool’. However, they noted that

contributors must be informed when a new comment

is added on their experience sheet. Moreover, unlike

comments left within classic social networks, SCP

collaborators asked for moderation and archiving of

comments to improve their readability and to control

potential excess or harassment in relation to co-

workers. Validators (collaborators with enough

expertise who are in charge of electronic validation of

experience sheets) will manage and ensure that

propositions made within comments are effectively

taken into account for the improvement of sheets.

They are also in charge of archiving comments.

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

224

The ‘Like’ functionality gave rise to much

discussion. Some participants had concerns about the

real meaning of the term ‘like’, potential abuse (if a

‘Like’ is just given by affinity and does not reflect the

quality of a contribution) and the negative impact it

could have on contributors’ motivation if they do not

receive any. Some participants thus asked for

clarification by relabelling the functionality to ‘useful

sheet’. Others were very enthusiastic about it as they

are already familiar in other social networks and

consider it as ‘playful’ in a professional context.

During the next session, where the resulting feature

was shown to users, they finally argued that the ‘Like’

functionality, in the context of SCP, is not a key

motivator for contribution but rather signifies the

reactivity of other collaborators and the awareness of

their feedback, the feeling of being in a human

community that works. Ultimately, they agreed to

consider ‘Likes’ as assessments of the sheet’s content

usefulness expressed by readers and to leave the term

‘like’ as is. Some adaptations have however been

requested: replace the raised thumb by a smiling

emoticon, and initiate discussions, among

collaborators, on this social functionality to prevent

the risks of misunderstandings and abuse.

3.3.2 Activity Indicators

Several pieces of information were proposed as

representative of reflexive indicators: notifications of

new publications, authors and date of submission, last

sheets read, view of contribution status, number of

comments received on a sheet. The view of

publications and number of comments did not trigger

any discussion as they have been already discussed in

previous sessions (see Figure 2 zone 3,4).

Notifications of new contributions published or

consulted were mentioned to facilitate the

identification of recent information and the interests

of other collaborators. The identification of the actors,

such as the last contributor or the last reader, was

deemed useful for initiating direct discussions

between colleagues. However, the identification of

the successive contributors was not considered

necessary, a validated form being considered as a

collective work. The status of publications (pending,

rejected, and accepted) has emerged due to the

expressed need to know if and when the validator has

taken into account a contribution. Finally, by

considering possible use cases, the discussions

revealed two ways of presenting these indicators: in a

personal page linked to profiles (see Figure 2 zone 6

for access) and on COs front pages. The first page was

seen as a way for each collaborator to follow his / her

Figure 2: View page of a content form.

own activity and see its scope within the organization.

The second was seen as a means for identifying the

dynamics of a community, updated or useful

information and thus initiating discussions among

colleagues.

3.3.3 Information Quality Indicators

Three indicators were proposed to express

information quality: readability, completeness with

respect to the concept described and relevance (Lee,

et al., 2002). The objective is to inform the user of the

reading effort necessary to realize the information

presented in real situations of work or problem

solving. There was general support for the use of such

indicators. Discussions focused on evaluation scales,

how values were allocated, and the names of

indicators. To describe readability, participants

proposed a 4 level scale: operational (the information

on the sheet is immediately or quickly exploitable,

such as alarms records specifically describing each

step to perform a corrective maintenance operation);

support (can be used in case of emergency but

requires more analysis for information

appropriation); acquisition (general information to

train the reader); and sharing (information that needs

further work). An agreement was reached on the term

‘presentation level’ to name the indicator.

Completeness was found useful using the name

‘Level of coverage’. The evaluation scale of this

indicator is on three levels: weak, medium and good.

This indicator was not deemed appropriate, as content

is relevant if accepted for publication by the validator.

As with the readability indicator, the completeness

assessment of the sheet is made by the validators. The

participants did not deem it useful to depict this

indicator with an icon (stars, lights ...) and preferred

How to Promote Informal Learning in the Workplace? - The Need for Incremental Design Methods

225

the indications to be directly written in the header of

each content form (see Figure 2 zone 1).

4 EVALUATION

4.1 Methodology

A qualitative evaluation has been done to measure the

design quality and the potential learning

effectiveness. Criteria for design quality are deriving

from uses success factors identified in the TAM,

UTAUT and ISSM models of technology acceptance

(DeLone and McLean, 2003; Venkatesh et al., 2012):

Use (Use), Usefulness (Usef), Satisfaction (Sat),

Percieved benefit (Ben), Usage intention (UI).

Indeed, successful use of the tool is related to positive

satisfaction, attitude and intention; this is why we

focus on these criteria. We measured learning

effectiveness according to users’ statements on

impact on use, work habits and performance

(IOU&W).

ALEX with social functionalities was made

available for four months. Ten collaborators have

been interviewed about their uses and positions about

new social functionalities. A first group (group 1) was

composed by five of them (named P1 to P5) that had

participated to the design working group, while a

second group (group 2) was composed by five other

people (named P6 to P10) who were not involved at

all in ALEX design. Interviews were individual and

lasted one hour per person. During the interview, an

interface of ALEX was available to help participants

to contextualise and refine their appreciations. The

interviews were anonymously recorded and manually

encoded to identify the parts of sentences, called

utterances, corresponding to the different criteria. A

positive (+), neutral (=) or negative (-) polarity was

assigned to each selected utterance. An utterance was

considered as neutral when participants said that they

did not know how to answer a question or when it was

not possible to detect a polarity in the given answer.

We analysed participants’ appreciations according to

the number of statements and polarity on each criteria

and compare the two groups to measure if the

working group proposition are shared with the other

collaborators.

4.2 Results

4.2.1 General Results

111 utterances (n=111) were collected. Table 1

describes their distribution according to the six

criteria and the three polarities in frequency and

percentage. We note that appreciations are globally

positive (60.2%). Only 11.3% are negative and 28.5%

are neutral. Usefulness is the most expressed

statement (40) and is globally positive (52.5%) even

if one third of the participants don’t have an accurate

point of view about it (32.5%). Satisfaction and

impact on work and performance are the most

positive criteria (with respectively 90% and 72.7%).

A third of the participants (35.7%) express positive

statements about usage intention while nearly half of

them (42.8%) have no real idea of the kind of usage

they can introduce. Statements about real uses are

diverse. Half of the participants express positive uses

(50%) but a third of them (31.3%) didn’t use Alex.

Comments of participants related to each criteria

presented in the section 4.2.3 are useful to refine and

understand these results.

Table 1: Distribution of utterances according to criteria

(frequency) and polarities (percentage).

Use Usef Sat Ben IOU&W UI Means

n

16 40 20 10 11 14

+ (%)

50 52.5 90 60 72.7 35.7 60.2

- (%)

31.3 15 0 0 0 21,4 11.3

= (%)

18.7 32.5 10 40 27.3 42.9 28.5

Table 2: Group 1 and 2 comparison.

Use Usef Sat Ben IOU&W UI

+ (%)

37.5 25 35 20 27.3 7.1

Group 1 - (%)

6.3 5 0 0 0 7.1

= (%)

12.5 7.5 5 30 18.2 28.6

+ (%)

12.5 27.5 55 40 45.5 28.6

Group 2 - (%)

25 10 0 0 0 14.3

= (%)

6.3 25 5 10 9.1 14.3

4.2.2 Group Answers Comparison

Table 2 shows the distribution of positive, negative

and neutral responses among people from groups 1

and 2. People in group 2 express more satisfaction

than in group 1. This corroborates the fact that we

succeeded in transcribing future users’ needs. This is

the same for usefulness, benefits and usage intention,

for which we collected more positive appreciations

from the participants who were not involved in the

design. This may be related to the surprise effect and

let’s expect a motivating effect for further use. The

negative appreciations about usefulness in group 1

were given by participant P4 concerning quality

indicators. This can be explained by the position of

the participant (engineer) and his seniority. He stated

that “engineers use ALEX only in specific

maintenance operation periods”. As he is an expert,

quality indicators do not have particular usefulness

for him.

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

226

4.2.3 Comments of Participants Related to

Each Criteria

The participants provided us with very valuable

comments. A more complete transcription of these

interviews can be found in (Touré et al, 2017). Here,

we give the most salient comments.

Usefulness. Six out of ten participants explicitly

found comments functions useful: four from group 2

and two from group 1. Three out of ten participants

explicitly found indicators useful. One relates that:

“… in the previous version of ALEX, we couldn’t

really rely on sheets during maintenance

operations… as the information evolves rapidly,

when someone notices a mistake or something else…

it was discussed face to face with the person supposed

to operate the sheet’s modifications … which was

done… or not… for me, comments are a feature more

rewarding than oral exchanges, comments come from

everyone… a trace of their viewpoint is kept, less

chance of forgetting or losing information as was

common in previous versions”. Indeed, having up-to-

date information is an important part of information

quality, positively related to an effective use of the

platform (DeLone and McLean, 2003) by two

participants from group 2 and one from group 1.

Concerning ‘Likes’, three out of ten participants

explicitly found this functionality useful: one from

group 2 and two from group 1. One participant

qualified as “sympathetic” the idea of adding this

social functionality and highlighted “a lack of

communication and social components in the

previous version of ALEX”.

User satisfaction and benefits. Participant

generally find the platform more modern and

satisfactory overall; they did not find many negative

aspects. Participant P1 said that ALEX was “a

renovated tool, similar to those findable in the

internet market, more playful and pleasant”, while

participant P4 argued that Alex was “more user-

friendly”. They express benefits to use new

‘comment’ and ‘Like’ functionalities. Participant P5

employed the phrases “peers’ acknowledgment and

feeling useful”. Participant P3 said: “…as it is now

easier to use, we have more time to submit and seek

for information… I am personally satisfied to

participate in the building of the tool… inter alia to

help the new colleagues integrating in the company…

but I would like to be aware of my exact role in the

tool and also have a kind of acknowledgements from

the company…” In these words, we identify the belief

of social influence which arises from the use of the

tool and motivates users. This is an interesting

finding, as intrinsic benefits like reputation, joy and

knowledge growth positively leverage continued use

of knowledge-sharing tools (He & Wei, 2009).

Impact on use and on performance. At the time

of the interviews, most participants did not mention

any significant increase of ALEX use compared with

how they used the previous versions. Four out of ten

participants were frequent users (from twice a week

to every day, according to the working tasks to

perform), while the remainder used it once a month

or less. When asked why, most of them answered that

they had enough experience and knowledge of the

hydraulics infrastructures. They also justified this by

the fact that they were rarely confronted with difficult

or atypical issues they didn’t already know how to

deal with, or needed more frequent connection to

ALEX. Nevertheless, three participants argued that

ALEX had been “a time saver to access unknown

intervention venues” and useful to “get information

about the components of my new OC”, or to assist him

“during a drain, a common maintenance operation”

in water infrastructures. The two first ones were new

to the OC, and the last one had a complex

maintenance operation to perform.

Usage intention. About half of the participants

expressed usage intention linked with information

seeking. Few of them plan to submit and collaborate

on ALEX’s content. However, the score 42.9% of

neutral appreciation rate (see Table 1) can be

explained be the youth of the project and the

particular conditions of the context. For example,

participant P2 was about to leave SCP (termination of

his contract). He nevertheless participated in the

evaluation and specified that “ALEX usage

perspectives are positive … under the conditions of a

general advertisement campaign within the

company…”. Participant P1 also stressed the positive

effect of the user-centred design approach on

workers’ involvement and on sustainability of the

new ALEX: “… everyone participated in the

refinement of the tool, the result satisfied more people

and strengthened the project… everyone sees more

clearly its real interest, which was not necessarily the

case before, so I think it will be continuously used

…”.

4.2.4 Conclusion about Evaluation

The qualitative evaluation we conducted showed that

workers were satisfied with their new tool. We also

noticed that new beliefs arose from the use of the tool,

such as social reputation, usefulness and joy.

Participants showed positive usage intention,

especially for information seeking, which is a way of

knowledge verification and learning. However, the

How to Promote Informal Learning in the Workplace? - The Need for Incremental Design Methods

227

usage frequency did not change, as workers

considered themselves too experienced to change

their habits. This is not surprising, as learners most of

the time are poor at estimating their skills, but this can

change by learning and improving their

metacognitive skills (Glenberg, Wilkinson, &

Epstein, 1982; Kruger & Dunning, 1999). We believe

that this will have a positive impact on the tool usage

in the long term. Further evaluation certainly needs to

be done, but these outcomes corroborate the fact that

our methodology plays a role in sustainable use,

defended by our generic cycle of improvement of

technologies. People engagement is supported half by

involvement in the design methodology and half by

the social functionalities that give positive beliefs and

usage intention. Designers help users to express their

latent needs and transcribe them; experts have roles

as content validators and community moderators; and

the other workers participate in the community.

Results give us positive insights into the sustainability

of our proposed model for informal learning.

5 DISCUSSIONS AND

CONCLUSION

Our analysis showed that ESM are appropriate to

support informal learning strategies in the workplace.

Indeed, social features like comments, appreciations,

activity indicators are adapted to stimulate use

behaviors and support learning, particularly meta-

cognitive aspects. Three adaptations must

nevertheless be carried out: (1) Base the design on a

precise and relatively exhaustive informational

corpus of the procedures and know-how already

formalized in the company and contextualize the

access in the form of community of practice

structured according to collaborative spaces; (2) Add

indicators of judgment on the operational quality of

information and the informational capital built, and

(3) Define forms of moderation and control consistent

with the hierarchical structures of the company. Our

analysis also showed that an incremental and iterative

approach of user-centered design had to be

implemented to define how to adapt the design and to

accompany change.

The reinforcement of the design work on

information architectures, in terms of content,

structuring and publication, is not contrary to the

principle of social media. Evaluation shows that

information seeking is a massive use intention. It thus

could be useful to refine this work for proposing

information search recommendation based on users'

tracks. On the other hand, the need to adapt forms of

moderation and control to the hierarchical structures

of the company questions us. This principle is

coherent with learning objectives since it creates

some forms of mediation but is less so if one

considers the principles of social media which consist

in smoothing these forms of hierarchies to highlight

the speech of each moderated by the collective. We

wonder whether it is realistic to add this additional

work load. Its implication is indeed critical to

guarantee this type of functioning. In addition, we are

wondering whether these requirements are indeed

sustainable over the long term or whether they are an

acceptance step in the design cycle as a form of

temporary guaranty that should fall after the use of

this type of platform all over the company.

The evaluation conducted shows promising

results about uses and effects on the satisfaction and

the feeling of learning after three months of use. On

this basis, our next objectives will be to extend the

deployment of the platform to all OCs to observe the

acceptability of the principles to the whole

organization, the informal learning effects and answer

more general questions about the Forms of

moderation.

REFERENCES

Ackerman, M. S., Dachtera, J., Pipek, V., & Wulf, V., 2013.

Sharing Knowledge and Expertise: The CSCW View of

Knowledge Management. In Computer Supported

Cooperative Work (CSCW), 22(4–6), 531–573.

Bancheva, E., & Ivanova, M., 2015. Informal learning in

the workplace. In Private World(s): Gender and

Informal Learning of Adults, 157–182.

Benson, A. D., Johnson, S. D., & Kuchinke, K. P., 2002.

The Use of Technology in the Digital Workplace: A

Framework for Human Resource Development. In

Advances in Developing Human Resources, 4(4), 392–

404.

Bhattacherjee, A., Limayem, M., & Cheung, C. M. K.,

2012. User switching of information technology: A

theoretical synthesis and empirical test. In Information

and Management, 49(7–8), 327–333.

Bhattacherjee, A., 2001. Understanding information

systems continuance: an expectation-confirmation

model. In MIS Quarterly, 25(3), 351–370.

Commission of the European Communities, 2000. A

Memorandum on Lifelong Learning, Retrieved from

http://arhiv.acs.si/dokumenti/Memorandum_on_Lifelo

ng_Learning.pdf.

DeLone, W. H., & McLean, E. R., 2003. The DeLone and

McLean Model of Information Systems Success : A

Ten-Year Update. In Journal of Management

Information Systems, 19(4), 9–30.

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

228

Dennerlein, S., Theiler, D., Marton, P., Santos Rodriguez,

P., Cook, J., Lindstaedt, S., & Lex, E., 2015.

KnowBrain: An Online Social Knowledge Repository

for Informal Workplace Learning. In 10th European

conference on technology enhanced learning, EC-TEL

2015, Toledo, Spain, september 15–18, 2015

proceedings, Vol. 9307, 509–512.

Ellison, N. B., Gibbs, J. L., & Weber, M. S., 2015. The Use

of Enterprise Social Network Sites for Knowledge

Sharing in Distributed Organizations: The Role of

Organizational Affordances. In American Behavioral

Scientist, 59(1), 103–123.

Ersoy, M., & Güneyli, A., 2016. Social Networking as a

Tool for Lifelong Learning with Orthopedically

Impaired Learners. In Journal of Educational

Technology & Society, 19, 41–52.

Graesser, A. C., 2009. 25 principles of learning. Retrieved

October 11, 2016, from

http://home.umltta.org/home/theories/25p

Graesser, A. C., 2011. CE Corner: Improving learning. In

Monitor on Psychology, 2–5.

Hager, P., 2004. Lifelong learning in the workplace?

Challenges and issues. In Journal of Workplace

Learning, 16(1/2), 22–32.

Hahn, J., & Subramani, M. R., 1999. A framework for

knowledge management systems : issues and

challenges for theory and practice. In ICIS'00

Proceedings of the twenty first international conference

on Information systems, 302–312.

He, W., & Wei, K.-K., 2009. What drives continued

knowledge sharing? An investigation of knowledge-

contribution and -seeking beliefs. Decision Support

Systems, 46(4), 826–838.

Janssen, J., Erkens, G., & Kirschner, P. A., 2011. Group

awareness tools: It’s what you do with it that matters.

In Computers in Human Behavior, 27(3), 1046–1058.

Jennex, M. E., & Olfman, L., 2006. A Model of Knowledge

Management Success. In International Journal of

Knowledge Management, 2(3), 51–68.

Kaplan, A. M., & Haenlein, M., 2010. Users of the world,

unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social

Media. In Business Horizons, 53(1), 59–68.

Kietzmann, J. H., Hermkens, K., McCarthy, I. P., &

Silvestre, B. S., 2011. Social media? Get serious!

Understanding the functional building blocks of social

media. In Business Horizons, 54(3), 241–251.

Kulkarni, U., Ravindran, S., & Freeze, R., 2007. A

knowledge management success model: theoretical

development and empirical validation. In Journal of

Management Information Systems, 23(3), 309–347.

Lee, Y. W., Strong, D. M., Kahn, B. K., & Wang, R. Y.,

2002. AIMQ: a methodology for information quality

assessment. In: Information & Management, 40(2),

133–146.

Leonardi, P. M., Huysman, M., & Steinfield, C., 2013.

Enterprise social media: Definition, history, and

prospects for the study of social technologies in

organizations. In Journal of Computer-Mediated

Communication, 19(1), 1–19.

Longmore, B., 2011. Work-based learning: bridging

knowledge and action in the workplace. In Action

Learning: Research and Practice, 8(4), 79–82.

Pettenati, M., & Ranieri, M., 2006. Innovative Approaches

for Learning and Knowledge Sharing. In E. Tomodaki

& P. Scott (Eds.), Innovative Approaches for Learning

and Knowledge Sharing, EC-TEL 2006 Workshops

Proceedings, 345–355.

Riemer, K., & Scifleet, P., 2012. Enterprise Social

Networking in Knowledge-intensive Work Practices :

A Case Study in a Professional Service Firm. In 23rd

Australasian Conference on Information Systems, 1–

12.

Schön, D. A., 1987. Educating the reflective practitioner:

Towards a new design for teaching and learning in the

professions, Jossey-Bass Edition, Oxford and San

Francisco.

Sharples, M., 2000. The design of personal mobile

technologies for lifelong learning. In Computers &

Education, 34(3–4), 177–193.

Stocker, A., & Müller, J., 2013. Exploring Factual and

Perceived Use and Benefits of a Web 2.0-based

Knowledge Management Application: The Siemens

Case References +. In Proceedings of the 13th

International Conference on Knowledge Management

and Knowledge Technologies.

Touré C., Michel C. & Marty J.-C., 2015. Refinement of

Knowledge Sharing Platforms to Promote Effective

Use: A Use Case. In 8th IEEE KARE Workshop in

conjunction with 11th SITIS International Conference,

Nov 2015, Bangkok, Thailand, 680-686.

Touré C., Michel C. & Marty J.-C., 2017. Towards

extending traditional informal learning tools in the

workplace with social functionalities. In International

Journal of Learning Technology, 34p. (to be published

in 2017).

Turban, E., Bolloju, N., & Liang, T.-P., 2011. Enterprise

Social Networking: Opportunities, Adoption, and Risk

Mitigation. In Journal of Organizational Computing

and Electronic Commerce, 21(3), 202–220.

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Hall, M., Davis, G. B., Davis,

F. D., & Walton, S. M., 2003. User acceptance of

information technology: Toward a unified view. In MIS

Quarterly, 27(3), 425–478.

Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y. L., & Xu, X., 2012. Consumer

Acceptance and Use of Information Technology:

Extending the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use

of Technology. In MIS Quarterly,36(1), 157–178.

Wang, S., & Noe, R. a., 2010. Knowledge sharing: A

review and directions for future research. In Human

Resource Management Review, 20(2), 115–131.

Wenger, E., 2006. Communities of practice: A brief

introduction. Retrieved from

http://www.ewenger.com/theory.

Zhao, X., Salehi, N., & Naranjit, S., 2013. The many faces

of Facebook: Experiencing social media as

performance, exhibition, and personal archive. In

Proceedings of the CHI'13 Conference, Paris, 1–10.

How to Promote Informal Learning in the Workplace? - The Need for Incremental Design Methods

229