Knowledge Processes in Virtual Teams

Tacit Knowledge

Birgit Großer

1

, Sara Kepplinger

2

, Cathrin Vogel

3

and Ulrike Baumöl

1

1

Chair for Information Management, FernUniversität Hagen, Universitätsstr. 41, Hagen, Germany

2

Fraunhofer Institute for Digital Media Technology IDMT, Ehrenbergstr. 31, Ilmenau, Germany

3

Department of Instructional Technology and Media, FernUniversität Hagen, Universitätsstr. 33, Hagen, Germany

Keywords: Tacit Knowledge, Virtual Teams, Knowledge Processes, Enterprise Information Systems.

Abstract: The deployment of virtual teamwork superseding traditional work structures provides ample opportunities

for organizations regarding e.g., cost efficiency and employee retention. Many organizations embrace the

potentials of virtual teamwork, being it modern enterprises such as start-ups or traditionally set companies

integrating more virtual solutions along their evolution. Virtual teams create value by processing knowledge

through the creation, transfer, retention and application of knowledge. Knowledge consists of explicit

knowledge and hard to capture tacit knowledge. As tacit knowledge cannot always be easily converted to

explicit knowledge in form of written documents, the knowledge processes for virtual teams are constituted

differently regarding tacit knowledge. The reliance on information and communication technology for

processing tacit knowledge introduces further challenges but also opens up new approaches, e.g., by

working in three dimensional virtual environments. The paper at hand presents an exploratory case study

about how knowledge processes regarding tacit knowledge manifest themselves in virtual teams and what

technological solutions are relevant as support. A case study is performed and implications for the

implementation and technological support of knowledge processes for tacit knowledge are derived.

1 INTRODUCTION

The welfare of today´s society bases – more than

ever – on knowledge: Most of the latest innovative

and successful business models rely on data and

with that on knowledge. Working on data,

information and knowledge is extensively supported

by technology. This enables employees to work

mobile, flexible and remotely, e.g., in virtual teams

(VTs). The business potential of virtual teamwork

supported by information and communication

technology (ICT) is considerable. Virtual teamwork

can lead to a continuous workflow due to

asynchronous working hours within a team.

Traveling and office expenses can be cut when

employees do not need office buildings. Moreover,

the value creation of traditional business models

depends on the transfer of knowledge and its

application. As a consequence, the profile of the

knowledge worker is not only common, but also

predominant in most of the industrialized countries,

in new as well as in traditionally set companies.

Today, we face two major changes with respect to

the socio-technical prerequisites for knowledge

work: First of all, individuals are much more ready

to share knowledge and actively participate in the

development of collective solutions (Von Krogh, et

al., 2012). In addition to that, the current and

upcoming workforce is used to work with ICT in

their private as well as in their work life. Thirdly,

technical solutions for supporting knowledge work

have become much easier to use and, more

importantly, more “social” in many aspects.

Employees process knowledge, being it deliberately

or unknowingly, when they create, transfer, retain

and apply knowledge. The common distinction of

knowledge into explicit (EK) and tacit knowledge

(TK) (Elmorshidy, 2016) is applied for our research.

The processes for EK are widely and well known,

e.g., writing, storing, or transferring knowledge. In

contrast to that, processes creating and managing TK

are less transparent and well defined (Alavi &

Tiwana, 2002). Especially, when work happens in

VTs the processing and capturing of TK becomes

more challenging since the personal contact is

missing. As a consequence, the processes need to be

Großer, B., Kepplinger, S., Vogel, C. and Baumöl, U.

Knowledge Processes in Virtual Teams.

DOI: 10.5220/0006674602470254

In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2018), pages 247-254

ISBN: 978-989-758-298-1

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

247

adapted and supported with appropriate ICT. Based

on these prerequisites, more options to organize

collaborative work and with that knowledge sharing

environments arise. As VTs are considered an

efficient way to organize knowledge work, more and

more companies look into the potential of

virtualization of teams and try to understand the

mechanisms for their functioning.

VTs are by no means new as research objects.

Extensive research offers insights on various aspects

of VTs (Gilson, et al., 2015). Besides general

analyses of knowledge processes in VTs (Fang, et

al., 2014) (Rosen, et al., 2007) research on TK in

VTs offers only few observations. E.g., the

processes of how TK can be created (Diptee &

Diptee, 2013) and shared (Elmorshidy, 2016) by

VTs are analyzed. We advance these insights by

providing a holistic view on all four knowledge

processes (i.e., creation, transfer, retention and

application, see Section 2) regarding TK in VTs and

the derivation of guidance for their implementation.

The above mentioned changes in mind-set and

ICT support lead to new opportunities. At the same

time, it becomes relevant to think about the

requirements and processes regarding the challenges

introduced by TK for VTs (Alavi & Tiwana, 2002).

Thus, we focus on how to implement knowledge

processes for TK in VTs, by building on existing

knowledge from scientific literature and performing

an exploratory case study. Additionally, approaches

for implementing TK processing in VTs and links

for future researches are proposed.

This procedure and the derived research

questions are shown in Table 1. The left column

shows five components that are substantial for a

valid case study design (Yin, 2014). In the right

column we provide information on how and in what

order these components are implemented for the

case study at hand.

Therefore, Section 2 provides essential

definitions of the relevant concepts. In Section 3 the

case study performing interviews is presented. In

Section 4 the results of the study are synthesized

with the findings from literature in order to propose

approaches for knowledge processes regarding TK

in VTs.

2 CONCEPTUALIZATION

In order to address research questions RQ1 and RQ2

and their manifestations (see Sections 3.3 and 4)

VTs, TK, knowledge system and knowledge

processes, as well as factors influencing the transfer

Table 1: Key components and action plan.

Component of case

study design

Implementation and section

1. Research

questions

RQ1: How is tacit knowledge

processed in companies adopting

virtual teamwork?

RQ2: What are organizational and

technological solutions for effective

processing of tacit knowledge in

virtual teamwork? See Section 4.

2. Theoretical

propositions

Concepts for virtual teamwork, tacit

knowledge and knowledge processes

are derived in Section2.

3. Units of

analysis and

data

Interviews with one organization

were conducted, transcribed and

analyzed. See Section 3.

4. Linking data to

propositions

The results are mapped to the

knowledge processes and

approaches are proposed in Section

4.

5. Criteria for

interpreting

findings

Criteria and their manifestation are

described in Sections 3.3 and 4.

of TK are described in the following passages. The

virtualization of teamwork is analyzed regarding the

influencing drivers of business models (performance

promise, products and services, conditions of

production) as well as the organization and design of

the workplace (organizational and technical).

Teams in today’s work environment can be

characterized by different degrees of virtuality along

a continuum between more traditional and

completely virtualized teams (Schweitzer &

Duxbury, 2010). On the one hand, teams that can be

located towards the traditional end of the continuum

might use ICT so the team members do not have to

be in the same office all the time and are able to

work slightly different hours. Completely virtualized

teams on the other hand strongly rely on ICT for

being able to perform their tasks, not working face-

to-face and intensely asynchronously. This can be

presented by the use of collaboration platforms to

chat and exchange documents for the minor degree

of virtuality up to completely virtual teamwork,

where the employees are spread over the globe

performing any knowledge process via ICT. Modern

companies such as start-ups are often far more

virtualized than traditional companies or

organizations that introduce virtual teamwork for

certain tasks or special roles (Hanebuth, 2015). The

organization whose employees were interviewed

regarding their implementation of knowledge

processes (Section 3) represents a degree of

virtuality that is noticed to be prominent among

organizations of this size and age. The teams work

ICEIS 2018 - 20th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

248

in a traditional setting but use technologies for

virtual teamwork as their work requires increasing

mobility resulting in disperse and asynchronous

teamwork.

The ways of human interaction in work

environments are different for VTs compared to

traditional teams. In traditional teams, employees

meet in offices and can learn from each other by

literally watching each other work. VTs rely on ICT

for their everyday work, including all knowledge

related processes. ICT, like established video call

applications or virtual environments (VEs), preserve

the narrative structure and experience for distance

communication and enable virtual teamwork,

especially supporting the handling of TK (Haase, et

al., 2013). VEs include software applications, such

as three dimensional meeting rooms, opportunities to

work on virtual objects, the use of avatars for

communication, etc. As these applications differ in

their use and regarding opportunities for their

operation, knowledge related processes can be

assumed to be designed differently if the teams in

focus work virtually, due to the prerequisites of VTs

and their ICT use. Virtuality in teamwork becomes

even more challenging, when focusing on processing

TK in a virtual setting. TK is regarded to enable

people to create ideas through their experience of the

past and anticipation of the future. This ability is

crucial for developing advanced and innovative

ideas (Leonard & Sensiper, 1998). But as TK cannot

always be converted and passed on easily via written

documents (Martins & Meyer, 2014), human

interaction is needed for creating, transferring,

retaining and applying TK.

These knowledge processes are embedded in the

knowledge system which in this context covers all

areas of work systems (Alter, 2010). This does not

only include ICT but also the people involved,

organizational rules, and the processes performed.

Therefore, VTs and the deployed ICT are building

blocks of the observed knowledge system. (Section

3). Its processes can be defined as a sequence of

input, alteration and output in order to create value

(Heisig, 2009). Complying with this definition,

knowledge processes use knowledge as object of

alteration. Many different concepts of knowledge

processes are derived in literature (Heisig, 2009).

For the paper at hand the knowledge processes are

structured into creation, transfer, retention and

application of knowledge (Heisig, 2009). This

discrimination serves the analysis of different

knowledge related tasks and a reasonable mapping

of ICT to the knowledge processes. The process of

knowledge creation includes the generation of TK

from EK as well as from sources of mainly tacit

character (Liu, et al., 2008). Transfer of TK is

presented by the transfer from one to another person

happening within a team as well as the transfer

between teams. Factors influencing the quality of

transfer of TK are e.g., trust, reciprocity, and

organizational structure (Hao, et al., 2016). The

extent of the factors’ positive or negative influence

on TK transfer appears to follow complex dynamics

for each single case. There is no consensus in

literature concerning these influencing factors (Hao,

et al., 2016). The factors concerning TK transfer are

especially addressed by ICT, e.g., in user generated

social intranets (Elmorshidy, 2016). TK transfer is

also referred to as TK sharing in literature (Hao, et

al., 2016). Sharing stresses the dynamics of

reciprocity and intrinsic factors such as the

employees’ attitudes and intentions (Hao, et al.,

2016). As the concepts of sharing and transferring

TK are not consistently discriminated in literature of

different scientific fields, this paper and further

research can add to structuring these concepts.

Retention of TK can be realized by documentation,

implying the conversion of TK to EK (Martins &

Meyer, 2014). As TK cannot always easily be

converted, another way of retaining this knowledge

is within the carriers. Therefore, also employee

retention is of major importance, as not documented

TK would leave the organization with the employee.

The process of knowledge application is presented

by the actions of the knowledge carrier. The carriers

are not only hosts of the knowledge but apply it

through their work-related actions. Concerning TK,

ideas of carriers only have a positive effect on team

and company performance when they are actually

applied. This pertains to disruptive innovations as

well as to minor changes in everyday business.

Thus, this process is of major importance, although

not yet recognized by research and practice as much

as the other three knowledge processes described

above (Alavi & Tiwana, 2002).

Consensus has been achieved on the importance

of TK in work systems (Martins & Meyer, 2014).

Three arguments stressing the relevance of

knowledge processing of VTs are proposed by

(Fang, et al., 2014): Knowledge processes of VTs

impact individual and organizational learning. VTs

enable the utilization of knowledge across distances.

An effective handling of tasks by virtual teamwork

aims towards an efficient use of available knowledge

(Fang, et al., 2014). Virtuality of work settings,

including solutions from telework to 3D virtual

meetings, is assumed to affect knowledge related

processes in work systems (Diptee & Diptee, 2013).

Knowledge Processes in Virtual Teams

249

However, it does not become clear, how TK is

managed as a consequence of virtualization. Thus,

the effects of virtuality on knowledge processes for

TK and the related use of ICT are to be enlightened

in the paper at hand. In order to meet this goal, we

aim at deriving organizational and technological

approaches for processing TK in organizations

which strive for a virtual work environment. These

organizations are not founded as virtual companies,

but evolve from a less virtualized traditional setting

towards more virtual solutions.

The following case study addresses RQ1

regarding how TK is being processed in companies

adopting virtual teamwork. Based on the results of

this analysis, RQ 2, focusing on adequate solutions

for effective processing of TK in VT teamwork is

addressed.

3 CASE STUDY

The data considered in the following has been

collected in a foundation. It defines the status quo of

working, knowledge processing, communication

processes and their appreciation in this particular

foundation. The method of data collection (i.e.,

interviews) was pre-defined in consultation with the

foundation based on structural and organizational

issues. We extracted information relevant for RQ1

(see Table 1) focusing on the exploration of existing

processes related to TK.

3.1 Data Collection

In December 2016, interviews with ten employees

with the duration of one hour have been conducted.

These ten from more than hundred employees of an

around ten year old private and independent

foundation addressing socio-political topics were

from different levels of responsibility. Some of them

have to solve leading and organizational tasks,

others financial issues and a lot of them have tasks

mainly related to research and assessment. The

interviews were conceptualized in order to analyze

the current state of knowledge management

strategies and the usage of ICT applications in this

context. In sum, 49 mainly open questions without

pre-defined answer possibilities have been asked via

a video conference-system after having had an on-

site meeting with the interviewees once. All

interviews have been recorded and transcribed.

The interviewees cover a broad range of

hierarchical levels of the foundation. The

interviewees regularly work together as team, face-

to-face during the same office hours, but also work

virtually if a personal meeting is not possible. This is

the case when either being on business travels or

with external partners, customers, and experts.

Table 2 presents the analysis’ characteristics

(Benbasat, et al., 1987) and their implementation.

Table 2: The analysis’ characteristics and their implement-

tation.

Standardized characteristics

(Benbasat, et al., 1987)

Implementation

1. Phenomenon is examined

in a natural setting.

Processing of tacit

knowledge is analyzed in an

organization.

2. Data are collected by

multiple means.

Interviews are recorded and

transcribed as data collection

method.

3. One or few entities

(person, group, or

organization) are

examined.

Ten employees of one

organization are examined.

4. The complexity of the unit

is studied intensively.

The complexity is structured

by differentiating into four

knowledge processes.

5. Case studies are suitable

for the exploration,

classification and

hypothesis development

stages of the knowledge

building process.

The goal is to derive

organizational and

technological approaches for

how to process tacit

knowledge regarding virtual

teamwork.

6. No experimental controls

or manipulations are

involved.

The analyzed data was

collected and assessed

following the Grounded

Theory.

7. The investigator may not

specify the set of

independent and

dependent variables in

advance.

The dependent variables are

not set, but the research goal

induces virtual teamwork as

context for the independent

variables.

8. The results derived depend

heavily on the integrative

powers of the investigator.

The conceptualization of

tacit knowledge processes

and data analysis processes

support the integrative

potential.

9. Changes in site selection

and data collection

methods could take place

as the investigator

develops new hypotheses.

Changes in site selection or

collection methods are

regarded as opportunities for

validating the findings

though future research.

10. Case research is useful in

the study of “why” and

“how” questions because

these deal with operational

links to be traced over

time rather than with

frequency or incidence.

“Why” and “how” questions

are implemented in the data

collection. Ways for how to

process tacit knowledge are

extracted from the interview

data, supporting the

exclusion of arbitrariness.

11. The focus in on

contemporary events.

The focus is on current

developments and analyzed

regarding a currently

operating organization.

ICEIS 2018 - 20th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

250

Figure 1: Code model.

answers, the teams are considered to be currently

evolving from a less virtualized traditional setting

towards more virtual approaches. This evolvement is

furthermore based on the private media usage

behavior of the interviewees and on organizational

modernization activities.

3.2 Data Analysis

In order to answer RQ1 and prepare for RQ2, the

data set is categorized and analyzed deploying

common steps of the Grounded Theory approach

(Glaser & Strauss, 1998) going beyond a simple

content analysis and providing further hypotheses as

a result. As outlined in Table 2, the following

aspects (e.g., technical issues, “applications” (e.g.

social media, mail and phone)) and thereof clustered

categories (e.g., ICT, transfer, fast way of

cooperation, and tools) were defined, based on the

conceptualization proposed in Section 2. The

processes of knowledge creation, retention, transfer,

and application were used to code the answers of the

interviews. Based on these processes and after

analyzing the available interviewees’ responses by

two researchers, a systematic definition of categories

was done. The results are presented in the code

model in Figure 1 and discussed in Sections 3.3 and

4. The code model allows modeling while assessing

the results of the interviews. Once the categories and

underlying aspects were defined, the amount of

mentions regarding each category was counted. It is

recommended, that two researchers are executing

these activities independently of each other for valid

results. Therefore, and to avoid media bias one

researcher used MAXQDA

1

and one researcher used

1

MAXQDA is a professional research software for qualitative,

quantitative and mixed methods research for defining the code

theory model (online available: http://www.maxqda.com/)

pen and paper. Results were brought together after a

consistency check of the coding scheme (see Figure

1).

The chances and challenges ICT induces appear

to be of major interest for the interviewees

concerning TK management and a difference

between desired and existing culture of knowledge

management and knowledge sharing was revealed.

The code model provides an excerpt of the potentials

and issues seen in the TK management processes by

the interview partners. The available interviewees’

answers have been scanned regarding the categories

and their frequency was counted (i.e., how often an

aspect and a category were mentioned – not

necessarily designations, but interpreted meanings).

The coding leads to the results and hypotheses as

presented in the following section.

3.3 Results

The results of the interview analysis provide answers

to RQ1 regarding how TK is processed in companies

adopting virtual teamwork. The currently established

team structure can be located in-between traditional

and VTs as described above and the results represent

the challenges concerning TK and its current

handling. However, the results also provide an

insight about how TK could be represented in

knowledge systems used for virtual teamwork.

Most of the factors mentioned in the interviews

concerning TK are related to the knowledge transfer

process. Furthermore, in VTs working with unclear

task descriptions, communication between

colleagues is significant. The mentioned skills lead

to the conclusion that the employees working in

teams are required to be responsible for their

decisions and processes and innovative at the same

time. They express a tension between these job

requirements. Furthermore, their work relies on TK

ICT

messenger usage

Tacit knowledge (TK)

application

creation

problematic transfer

transfer

confer with colleagues

understanding of knowledge

management / relation to TK

seen potential

improved working coordination

more reliability

unclear responsibility

better knowledge

management

fast way of cooperation, tools

retention

Knowledge Processes in Virtual Teams

251

and should be handled in an organized way with and

in ill-structured situations. Due to this, it is not

surprising, that communication is important for the

employees to share experiences, discuss topics and

processes. The interviewees state they all receive an

average amount of fifty emails per day and

collaborate via sharing and commenting texts. On

the one hand, it is stated that using emails and chats

causes a lack of being able to convey complex TK

that could be transmitted better via personal contact

or videoconferences. An advantage of synchronous

contact is that wrong or missing information can be

communicated faster, compared to asynchronous

email contact. On the other hand, some interviewees

elucidate that asynchronous conversations have the

advantage of not interrupting thinking processes, as

spontaneous calls may do. Consequently, the

retrieval of information is problematic, because of

missing TK by a spillover of information. Changing

the ways of sharing knowledge, e.g., by using

knowledge management systems that structure

information in clusters, is regarded as supportive.

Being open minded and willing to share

knowledge is mentioned as important for successful

collaboration and communication. The importance

of personal communication is stressed, regarding

transferring knowledge in conversations with

colleagues and experts as well as in conferences.

This personal, direct transfer of experience is used

when facing new projects, tasks, and exceptional

situations, as well as for creative and training

processes.

Transfer and creation of knowledge are difficult

to distinguish in the interview results regarding the

moment creation takes place: Employees collaborate

to solve problems or act within unclear situations

and tasks. While searching for an advice, two people

share an experience and might be able (if willing) to

gain ideas or create new common practices and thus

knowledge for themselves. The application of

knowledge very much relies on pre-created TK in

form of not (yet) shared or converted knowledge

(e.g., experiences, not well documented best

practices), and on how it can be converted to EK and

used by other team members. According to the

interviewees, a common way to gain information is

searching online via search engines as a starting

point followed by offline (mostly informal) talks to

experts, research in specific journals and books.

Based on the interviewees’ answers, there are some

internal guidelines available within the organization

(e.g., how to start and finalize a project), but not

regarding creation, transfer and retention of

knowledge in a formal way. This leads to the

availability of a certain amount of TK which is

rarely transferred to EK. According to the

interviewees, such a transfer within the investigated

organization mainly happens after a private talk in

an informal way in which the persons involved

notice that similar research has already been

performed or certain knowledge is already available.

Yet, all the interviewed employees are willing to

share their knowledge with colleagues, if this

knowledge is important for them. Currently, this

happens via extensive meetings. In order to retain

TK, personal communication and meetings should

be structured and focused. The interviewees prefer a

to-do-list rather than a protocol after the meeting.

The documentation of meetings and project

results leads to the process of retention of TK. The

employees use tools for storing knowledge, in order

to keep access and share with colleagues. Virtuality

becomes more significant while being away on

business. ICT supporting virtual knowledge

retention are e.g. automated tracking tools for

communication and meetings, email applications

and organizational tools (e.g. trello or clouds).

However, several disadvantages were described

concerning ICT use: Using knowledge storage tools,

the knowledge stored is abridged, sometimes

unclear, unstructured and should be updated with

content. Such tools can furthermore distract from

work processes if they need to be updated manually.

This can be overcome by implementing automated

tracking tools, generating documentation from data

collected along written communication (email, chat)

and also tracking spoken communication in calls,

video-calls and virtual meetings in VE.

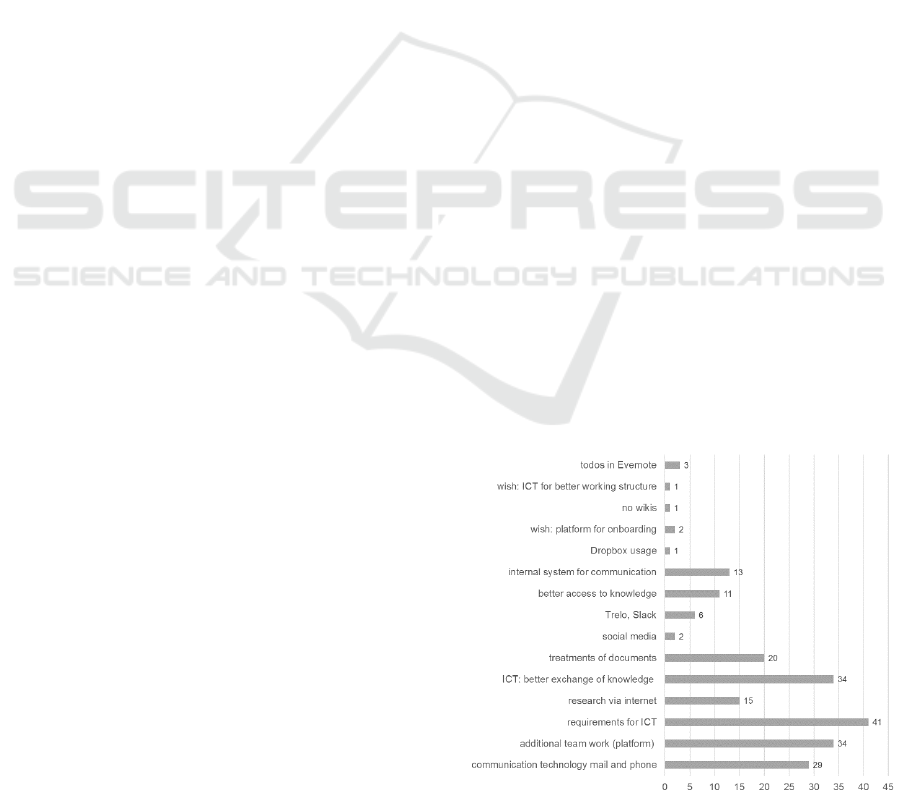

Interviewees see a problem in the often

unfiltered presentation of information. Figure 2

provides an overview of the frequency in the

interviews regarding the described categories. The

Figure 2: Frequency of categories related to ICT.

ICEIS 2018 - 20th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

252

majority is related to general ICT requirements,

followed by issues relevant in rather traditional

working environments (e.g., additional team work,

mail and phone, treatment of documents). Less often

mentioned topics are related to suggestions (e.g.,

that one would not like to use wikis or Dropbox) or

to wishes (e.g., use ICT for better working structure

or platforms for the special case onboarding). In

order to be able to transfer TK to EK and retain it,

interviewees see potential in user-friendly and

automated tools. These tools are required to combine

storage, support transfer and provide features for

retaining experience by transforming TK to EK.

4 DISCUSSION

Based on the results (Section 3.3), as derived along

the Grounded Theory approach, following

hypotheses are derived:

1 If team members are aware of the existence and

location of related TK, duplication of work (e.g.,

research to same or similar topic, definition of

best practices, and research for previous

experiences) would be avoided.

2 If TK is converted to EK, documented and

communicated in a continuous and constant way,

transparency concerning available knowledge

would be provided.

3 If the activity of knowledge documentation is a

complex and time-consuming task, it prevents

from doing the daily business and is, in sum, not

supportive.

These hypotheses and the according results

(Section 3.3) as well as the conceptual foundations

(Sections 1 and 2) are synthesized for addressing

RQ2, providing support towards solutions for

effective processing of TK in virtual teamwork. The

organizational implementation of the knowledge

processes for TK and the corresponding

technological support are shown in Table 3. The

results are presented for TK. Options for TK that

require or include the conversion to EK are marked

with (EK).

The results in Table 3 show, that creation of TK

does not necessarily require EK but relies on the

interaction with team members or other teams. In

order to support informal talks, open meeting rooms

could be established. These open meeting rooms

require an always online video room which can be

visited by employees e.g. during coffee breaks for

informal talks or can be attached to a personal

workplace. E.g., if a VT includes employees

working in two cities in office buildings, each office

Table 3: Implementation and technological support of

knowledge processes for TK in VTs.

Knowledge

process

Implementation

Technological

support

Creation

Online search, talk to

experts, informal talks

VE, open meeting

rooms

Transfer

To team member, to

other VT, using

clustered knowledge

VE, wiki (EK), email

and chat (EK)

Retention

Within carrier

(supported by

employee retention),

converted to EK for

storage

To-do-lists (EK),

wiki (EK), individual

handover (EK),

tracking tools (EK)

Application

Use of TK for tasks

VE, video calls

could set up a real room with some seating and an

always on online camera, so employees can

spontaneously meet, just as they are used to from

coffee breaks in traditional office settings. These

technological solutions need organizational support

for employees to recognize the benefits and for

supporting a technological progressive and open

minded culture within the organization.

Another technological opportunity that can be

applied for solutions such as VEs, chats and phone

calls is the tracking of conversations. The tracking

can be automated and the collected data can directly

be converted to EK using adequate algorithms. The

challenge for this opportunity is how to convert TK

that can be only correctly interpreted when cultural

aspects, tone of voice, gestures and content are

combined and mapped to the preconditions of the

recipient. Even though already several solutions

exist and research in this field is very active, this is a

highly relevant open link for further research.

5 CONCLUSIONS

TK proves to be a valuable but hard to capture

resource in knowledge processes of VTs. All four

identified knowledge processes are recognized to be

a challenge for VTs. But these challenges can be

addressed by organizational and technological

solutions as shown in this paper. The main results of

the interviews conducted among the employees are

that communication rules are helpful, but must not

be too detailed and complicated and need to be

coherent across teams. In order to provide

transparency concerning available knowledge, rules

need to be documented and communicated.

Knowledge processes regarding TK are

represented in a similar way in work environments

for VTs and traditional teams regarding retention

and application of knowledge. Challenges occur

Knowledge Processes in Virtual Teams

253

through virtuality concerning knowledge creation

and transfer. These can be addressed by inducing

communication and documentation rules, as well as

by using ICT for synchronous teamwork, such as

VEs (RQ1 and RQ2). Organizational knowledge

processes meet the requirements of individual

knowledge processes when providing supportive

management of TK. This leads to an organizational

culture of enabling and valuing knowledge work.

Even though the interviews provided relevant

insights, drawing ideas from interviews in one

organization only can be regarded as limitation of

this work. As the selected organization represents a

common size and degree of virtualization, the results

are nevertheless assumed to represent a large group

of organizations. However, there are open points,

concerning managing and supporting the harvesting

of TK through ICT. Knowledge creation and

application can be measured using respective reports

(Argote & Ingram, 2000). As this is more difficult

when surveying TK, further research is required to

provide report applications and rules for TK.

Creation of TK is based on human interaction, e.g.

in VEs, and could be augmented by human-

machine-interaction and even machine-machine-

interaction as already tackled by research concerning

neuronal networks. This participation of machines

introduces further opportunities for reporting

through the immanent conversion of TK to EK in

digital devices. Knowledge conversion from TK to

EK, especially concerning experience-related issues

is also crucial for efficient work.

Besides the goal of knowledge retention, written

and oral discussions could be tracked for detecting

risk of troubles, serving as early warning system, but

at the same time introducing supervision and

impairing organizational trust. Therefore, the

support and governance of cultural changes that are

required when introducing new ICT are of major

importance. Built on the results from the research

above, effective VTs can be established for different

degrees of virtuality, based on organizational

foresight and new technological achievements.

REFERENCES

Alavi, M. & Tiwana, A., 2002. Knowledge integration in

virtual teams: The potential role of KMS. Journal of

the American Society for Information Science and

Technology, 53(12), pp. 1029-1037.

Alter, S., 2010. Work systems as the core of the design

space for organisational design and engineering. Int. J.

Organisational Design and Engineering, 1(1/2), pp. 5-

28.

Argote, L. & Ingram, P., 2000. Knowledge Transfer: A

Basis for Competitive Advantage in Firms.

Organizational behavior and human decision

processes, 82(1), pp. 150-169.

Benbasat, I., Goldstein, D. K. & Mead, M., 1987. The

Case Research Strategy in Studies of Information

Systems. MIS Quarterly, September, pp. 369-386.

Diptee, D. & Diptee, J., 2013. Tacit knowledge acquisition

in virtual teams. s.l., s.n., pp. 1-8.

Elmorshidy, A., 2016. Tacit knowledge strategic use in

organizations — A new model for creation, sharing

and success. Agadir, Morocco, s.n., pp. 1-6.

Fang, Y., Kwok, R. C.-W. & Schroeder, A., 2014.

Knowledge proces-ses in virtual teams: Consolidating

the evidence.. Behaviour & Infor-mation Technology,

33(5), p. 486–501.

Gilson, L. L., Maynard, M. T., Jones Young, N. C.,

Vainen, M. & Hakonen, M., 2015. Virtual Teams

Research: 10 Years, 10 Themes, and 10 Opportunities.

Journal of Management, July, 41(5), pp. 1313-1337.

Glaser, B. G. & Strauss, A. L., 1998. Grounded Theory,

Strategien qualitativer Forschung. Bern: Verlag Hans

Huber.

Haase, T., Termath, W. & Martsch, M., 2013. How to

Save Expert Knowledge for the Organization:

Methods for Collecting and Documenting Expert

Knowledge Using Virtual Reality based Learning

Environments. s.l., s.n., pp. 236-246.

Hanebuth, A., 2015. Success factors of virtual research

teams – Does distance still matter?. Management

Review, May, 26(2), pp. 161-179.

Hao, J., Zhao, Q., Yan, Y. & Wang, G., 2016. A brief

introduction to tacit knowledge and the current

research topics. Jeju, South Korea, s.n., pp. 917-921.

Heisig, P., 2009. Harmonisation of knowledge

management – comparing 160 KM frameworks

around the globe. Journal of Knowledge Management,

13(4), pp. 4-31.

Leonard, D. & Sensiper, S., 1998. The role of tacit

knowledge in group innovation. California

management review, 40(3), pp. 112-132.

Liu, Y., He, J., Xiong, D. & Zeng, Z., 2008. Managing

Tacit Knowledge in Multinational Companies: An

Integrated Model of Knowledge Creation Spiral and

Knowledge Fermenting. Tianjin, China, s.n., pp. 1-5.

Martins, E. C. & Meyer, H. W. J., 2014. Organizational

and behavioral factors that influence knowledge

retention. Journal of Knowledge Management, 16(1),

pp. 77-96.

Rosen, B., Furst, S. & Blackburn, R., 2007. Overcoming

Barriers to Knowledge Sharing in Virtual Teams.

Organizational Dynamics, 36(3), p. 259–273.

Schweitzer, L. & Duxbury, L., 2010. Conceptualizing and

measuring the virtuality of teams. Information Systems

Journal, 20(3), pp. 267-295.

Von Krogh, G., Haefliger, S., Spaeth, S. & Wallin, M. W.,

2012. Carrots and rainbows: Motivation and social

practice in open source software development. MIS

quarterly, 36(2), pp. 649-676.

Yin, R. K., 2014. Case Study Research. Design and

Methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

ICEIS 2018 - 20th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

254