Trust in and Acceptance of Video-based AAL Technologies

Sophia Otten

a

, Wiktoria Wilkowska

b

, Julia Offermann

c

and Martina Ziefle

d

Chair of Communication Science, Human-Computer Interaction Centre, RWTH Aachen University, Campus-Boulevard 57,

Aachen, Germany

Keywords: Trust, Video-based AAL Technology (VAAL), Technology Acceptance.

Abstract: Due to a growing demand and need for solutions that alleviate the strain on the overburdened healthcare

system, video-based ambient assisted living (VAAL) technologies offer a good alternative to support

individuals in need of help. In order to successfully implement such technologies into the living spaces of

individuals with care needs, factors that determine their trust in, and acceptance of, such technology need to

be examined in more detail. This study investigates perceptions on trust and its relationship with the

acceptance criteria of VAAL technologies. In a mixed-methods design approach using focus groups and a

questionnaire study, participants evaluated their trust and acceptance perceptions of VAAL technology and

assessed its benefits and barriers. Results revealed significant relationships between the variables, signalling

the relevance of understanding of how trust may influence the overall acceptance of VAAL technologies.

Recommendations for future studies as well as applications of the findings are made.

1 INTRODUCTION

As of this moment, there is both a shortage of

healthcare personnel that is expected to increase and

a growing demand of people with care needs (Michel

& Ercanot, 2020). These issues have been further

exacerbated by the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic and

will bring about multiple serious societal issues, such

as maintaining the relationship with physicians in

people with chronic diseases (Erquicia et al., 2020).

In order to combat these challenges, there are several

approaches to go about it. One of them, in an attempt

of digitalising processes in all sectors of the public,

are assistive technologies. These kinds of devices and

systems are designed to enable people with care needs

to live a more autonomous life and keep their quality

of life while still having support for their

requirements (Peek et al., 2014, Wahezi et al., 2021).

Specifically, ambient and assisted living (AAL)

technologies are a type of technology that is typically

used for monitoring health status and behaviours,

such as detecting falls or recognising movement

patterns. These include wearable or ambient-installed

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4027-5362

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7163-3492

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1870-2775

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6105-4729

sensors that are used in people’s homes or permanent

care facilities (Climent-Perez et al., 2020; Steinke et

al., 2012). More precisely, video-based AAL

technologies (VAAL) can be used to monitor

people’s behaviours and alert medical personnel

and/or family members in case of a medical

emergency without having to interact with the users.

However, many of these solutions are still under

construction and more information about their

potential is needed. While studies often focus on

technological or legal obstacles, the perspective of

potential users is often missing. It is therefore

important to investigate people’s acceptance of AAL

technologies and what plays into their decisions to

use them, conducting studies from a user-centred

perspective (Offermann-van Heek & Ziefle, 2019).

Perceived benefits and barriers are proven to make

it more or less likely for people to accept such

technologies (Jaschinski & Allouch, 2015;

Wilkowska et al., 2021). Some examples of potential

benefits are the (re)gained independence and health-

related security of immediate help, while some

examples of potential barriers include data

management, usability, and trust issues (Schomakers

126

Otten, S., Wilkowska, W., Offermann, J. and Ziefle, M.

Trust in and Acceptance of Video-based AAL Technologies.

DOI: 10.5220/0011785500003476

In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2023), pages 126-134

ISBN: 978-989-758-645-3; ISSN: 2184-4984

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

et al., 2021). In addition, other factors shape the AAL

acceptance by potential users, like privacy, perceived

control, attitudes towards AAL, medical necessity, as

well as the added value to their daily life (Jaschinski

et al., 2021; Offermann-van Heek et al., 2019).

The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM; Davis,

1989) has been widely used in technology acceptance

research. This model assumes that two key

components significantly influence the attitude

towards its use: 1) perceived ease of use a given

technology, and 2) perceived usefulness that relates

to the idea of how useful the technology is. These

components are closely related to the behavioural

intention to use and the actual use of this technology.

Current research on health-related technologies

applied TAM in different contexts, confirming the

predictive power and determining role of these

criteria for innovative technologies (Rahimi et al.,

2018; Alshammari & Rosli, 2020).

In line with trading off the benefits and barriers,

potential users consider trust in these systems to be

vital. Throughout the literature, trust has been

conceptualised a human belief and expectancy and is

considered and interplay of a trustors and a trustee

(McKnight & Chervany, 2001). For trust in medical

technology, three main dimensions are relevant: user,

technology, and context factors (Xu et al., 2014; Bova

et al., 2006). However, as the development and use of

technologies is rapidly advancing, a more nuanced

distinction of how people form trust in VAAL

technology is necessary. Research shows that whether

and how people trust a particular technology is

dependent on both factors relating directly to the

technology but also context-related influences, such

as trust in their physician (Qiao et al., 2015). This

suggests that trust is influenced by multiple aspects,

and the way how people form trust in technology is

complex. Specifically, trust in technology has been

shown to be crucial for later acceptance (Wilkowska

& Ziefle, 2019). Due to the different measurements

of acceptance and trust in (V)AAL technology across

studies, results might differ (Wilkowska et al., 2015).

Considering this gap, this empirical study aims at

identifying relevant trust factors for the use of VAAL

technology, applying a mixed method approach.

2 QUALITATIVE APPROACH

First, an interview study was run with the purpose of

identifying trust factors that are considered relevant

for trusting VAAL technology.

2.1 Procedure

Both interview groups were recruited in the social

network of the researchers and volunteered to take

part. Informed consent and permission to record was

obtained prior to the beginning. During the interview,

first, trust perceptions in the healthcare system were

explored. Secondly, AAL technologies with a focus

on video-based systems were explained. Next, trust

perceptions, requirements for trust, and benefits and

barriers about trusting VAAL technology were

discussed and participants were asked about how trust

changes and develops in health decisions. Lastly,

demographic variables (e.g., age, gender, health

status), but also, technical affinity, and experience

with medical technology were assessed.

2.2 Sample

Two focus groups were held on two occasions with

each five participants (50% female). Both interview

groups lasted roughly one hour, were audiotaped and

transcribed later on. The age range was 22 to 55 years

(M=30.2; SD=12.39). On a scale from 1 to 6,

technical affinity ranged at M=4.2 (SD=1.48). Seven

participants completed vocational training, two of

them are students. Four participants work in the

medical and four in a technical field. Eight of them

have experience with medical technology and two

have professional care experience. None of them

neither dependent on care by others nor have acute

diseases, but four of them reported chronic diseases.

2.3 Results

There were two key topics in users’ argumentation

lines that were relevant for trust in the VAAL

technology: data protection and information and

communication flow. Also, several trust-associated

criteria were found and are discussed below.

2.3.1 Data Protection

In this category, participants mostly referred to their

data being sealed from third parties. While they

reckoned that any technology can theoretically be

hacked, they did agree that in order for them to trust

the VAAL system, access to their data should have

the highest possible protection mechanism.

“Just as important is the issue of data protection,

because of course no one wants to be filmed in their

own four walls or have any sound recordings of

them published for whatever purpose. There are

enough crazy people who abuse data like that [...].

Trust in and Acceptance of Video-based AAL Technologies

127

So data protection is a very important point for

me.” (male, 24 y)

Data protection was also an important aspect for

trust in VAAL technologies. In addition, participants

felt more comfortable if they could decide who has

access to their data and how it is shared.

“In any case, data will be stored somehow if the

[VAAL system] is installed in my bedroom and if I

knew that someone could access it, of course I

wouldn't like it at all.” (male, 26 y)

The key component was knowledge about the

technology brought to the users in a truthful way.

According to them, the topic receives growing

interest over the last years (relevance). For this

factor, five items were constructed in the

questionnaire (data access and relevance).

2.3.2 Information and Communication Flow

This category was defined as the context in which the

technology was introduced, monitored, and used.

Participants mentioned that they would more likely

trust a VAAL system in their home if their physician

explained it to them well. Moreover, they felt more

secure in trusting if the person monitoring their

activity, e.g., in case of a fall, was someone with a

professional medical background. Conversely, they

would not trust a VAAL system if they felt that the

systems did not understand the severity of the

incident. Participants agreed that an overall

professional appearance mattered for their trust

development (professionalism).

“I would then, if something like that [a detected

incident]is checked again by another person, then I

would like to have the experienced person and not

the one who was maybe a gardener before and says,

"oh, let's have a look" and then sends someone off.

[...] It would be important to me that it is checked

again by competent people who have medical

experience.” (female, 52 y)

Another aspect of this was that participants

referred to understanding the mechanisms both

behind the actual technology, i.e. the source code, and

behind the bureaucracy, i.e. the financing of it. One

participant, working as a computer scientist, said that

his only condition for trust in VAAL technology

required an open-source code. Other participants

argued that this would not affect them as much seeing

as they lacked the technical know-how. They did,

agree that they wanted to be able to retrace how

VAAL systems end up with the user. Moreover, they

worried about financing these systems and who

would pay for the usage. They also referred to trusting

the systems more if the costs were covered by their

insurance companies.

“If the source code behind it is open source, i.e. if I

can see it, modify it and, as a computer scientist, I

can understand exactly what is happening there,

then for me trust is already given because I can

identify that for myself.” (male, 25 y)

“I have also written down transparency. So how

does the system work, how does it recognise that

there is a problem. Of course, people have to be

taught this, made aware of it, and older people in

particular understand it even less than we do

now..” (female, 24 y)

“Who finances this? Does the health insurance or

the long-term care insurance cover part of it, or do

you have to pay the whole cost yourself? Of course,

not everyone can afford that.” (male, 24 y)

Participants mentioned that information should not

only consider the technology, but also about the

processes and involved parties behind and around it

(information transparency). Participants also

agreed that whether or not the system worked well

was relevant to trusting it.

"I would also say competence, so it doesn't set off a

false alarm twenty times. That it works reliably and

doesn't notify someone when really only a pen fell

down. I mean once or twice is no problem, but if it's

all the time, I’m thinking 'Why do I have the thing

in the first place?'" (female, 22 y)

Regarding the technical competence of the

system, it was agreed that this was one of the most

important predictors of trust in the VAAL system.

Taken together, this factor consisted of

information transparency about and around the

technology, professionalism toward the potential

users, and technical competence. For this factor,

seven items were constructed in the questionnaire.

2.3.3 Associated Trust Criteria

This category pertained to individual perceptions of

benefits of VAAL systems bringing a surplus value to

their life, coded as health aspects. They also brought

up examples of having less strain on medical

personnel as well as more independence with the

VAAL system, i.e. relief in care.

“It [the VAAL system] would have to be a good

added value somehow. When I see that I am limited, I

would like to be able to try it out and be told that if I

ICT4AWE 2023 - 9th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

128

really fall down or hit the corner and hit my head and

can't press a button any more, that someone will

come. So if I could recognise an added value, that it

would make me more independent of other people, I

would trust it more.” (female, 52 y)

“So, of course, for the people who rely on the system,

it must be ensured that the system works well, because

normally you save a caregiver who is with you 24/7

and who watches over you, or relatives who make

sure that nothing happens to you, that you are well

and that you don't lie in your flat for two days and

can't move.” (male, 25 y)

Some aspects were highly individual, respecting

the need of empathy (i.e., emotional aspects) of the

system as a relevant trust considerations. Seven items

were constructed in the questionnaire (emotional

aspects, relief in care, and health aspects).

3 QUANTITATIVE APPROACH

On the basis of the focus group study, trust factors

were identified and classified in three categories.

Considering other variables in literature, i.e.,

acceptance measures, the following research

questions emerged:

RQ1: How are the identified trust factors evaluated?

RQ2: Which role do the associated trust criteria play?

RQ3: Are trust and associated trust criteria related to

the evaluations of VAAL technology?

RQ4: Which role do the trust categories play for the

evaluation of VAAL technology?

3.1 Methods

Data was collected by an online survey in summer

2022. Participants were recruited mostly via social

networks and the participation was voluntary.

3.1.1 Design of the Survey & Care Scenario

We first introduced participants to the main purpose

of the study, i.e. trust in, and acceptance of, VAAL

technology. We assured participants of a high

standard of data protection and informed that none of

their answers can be referred to them personally.

The online survey was divided into four parts.

First, participants indicated their demographic data

(i.e., age, gender, education, and professional

background). We also surveyed the respondents’

perceived health condition (1=”very bad” to 6=”very

good”), the health status as well as need for nursing

care. We also surveyed the usage of health-related

digital technologies as well as the purpose of the use.

In the third part, using a scenario-based method,

participants were introduced into the following

situation: “(…) You are 85 years old and live alone in

your house (...). Because you have several chronic

diseases, including hypertension and inflamed joints,

you take daily regulating medication. Recently, you

have been experiencing additional coordination

difficulties and you are increasingly unsteady on your

feet, especially at night. However, moving into a

retirement home is unthinkable for you, as you would

like to remain in your familiar surroundings. You

decide to install a VAAL system in your home.

Decisive for you is the technology for the fall

prevention, intervention, and the control of the daily

routine as well as the analysis of your mobility

behaviour. You are free to decide who you share the

data with (e.g., doctor, nursing service, relatives). If

changes in your health condition and activity status

are detected, these persons receive a notification.”

Thereafter, participants assessed the acceptance of the

use of assistive technologies for health reasons. They

responded to statements referring to benefits (e.g.,

sense of security, emergency notification) and

barriers for the use (e.g., invasion of privacy, concern

about surveillance). Respondents also evaluated

technology acceptance criteria according to TAM

(Davis, 1989), i.e., perceived ease of use, usefulness,

and the intention to use such technologies (7 items;

=.86) which were adapted to VAAL technology.

Finally, participants shared their opinions on trust

in VAAL technology. The trust items were related to

Data Protection (5 items; =.89), Information &

Communication Flow (7 items; =.69), and

Associated Trust Criteria (7 items; =.75). All items

were evaluated on six-point Likert scales.

3.1.2 Sample

After data cleaning, N=101 participants were

considered for the statistical analyses. The age of the

participants ranged from 18 to 83 (M=35.7 years,

SD=10); 64% of respondents were females. Most of

the respondents (50%) held a university degree, 22%

indicated general university entrance qualification

(22%). Of all participants, 12.9% had a vocational

baccalaureate diploma and 10.9% held a secondary

school degree as their highest educational

qualification, whereas 3% reported to hold a PhD.

The majority of the sample reported (very) good

health (58%) and 10% as mostly bad. Additionally,

42% respondents reported to suffer from a chronic

illness or physical impairment and 23% indicated to

Trust in and Acceptance of Video-based AAL Technologies

129

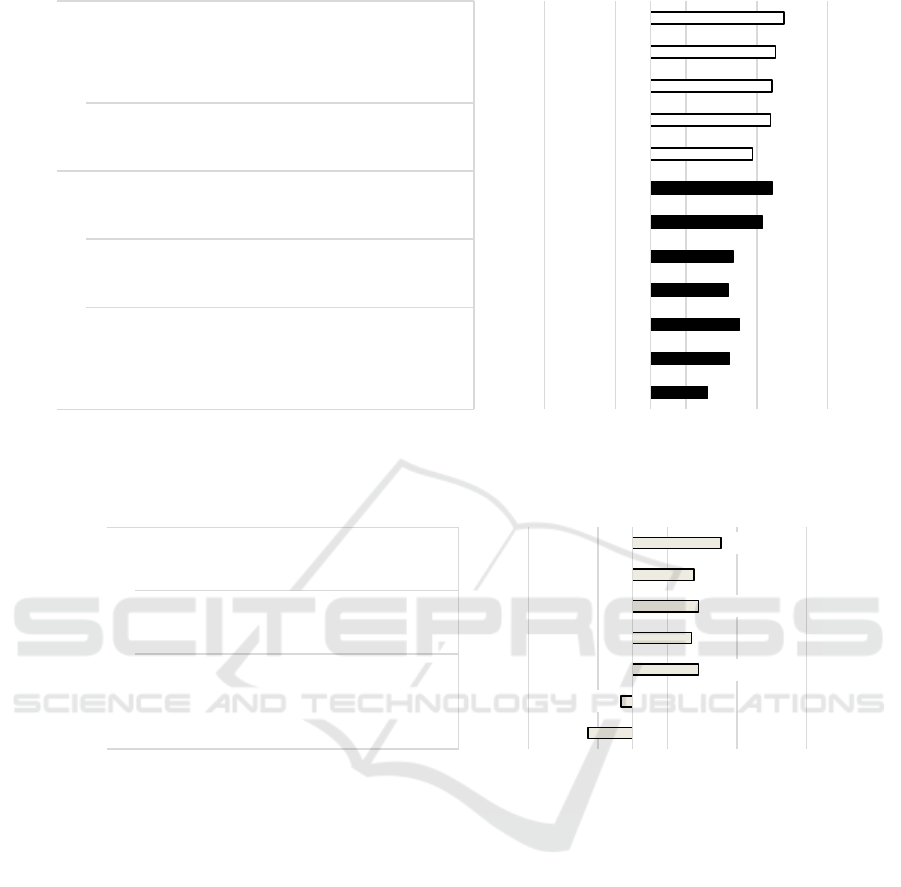

Figure 1: Evaluation of trust in VAAL technology (N = 101).

Figure 2: Evaluation of associated trust criteria (N = 101).

be affected by an acute physical or mental illness. 4%

needed care assistance (professional nursing or family

support). 53% of the respondents are actively using

health-assisting technologies (e.g., documentation of

vital parameters, monitoring of physical activities,

control of sleeping patterns, or weight control.)

3.2 Results

The quantitative results are described based on the

research questions. We used descriptive statistics for

the analysis of acceptance and trust statements

(M=means, SD=standard deviations). To examine

relations between the constructs we calculated

correlation analyses and examined the internal

consistency of the scales using Cronbach’s Alpha (

>.7). The significance level (p) was set at 5%.

3.2.1 Trust in Technology (RQ1)

Starting with Data Protection, all five items received

confirming evaluations. For the participants, it was of

major importance that they can decide “…who may

share…” (M=5.38; SD=.81), “…who sees…”

(M=5.26; SD=.91), and “…who may store…”

(M=5.21; SD=.92) their data. Further, they showed

strong agreements referring to the statements that

their “…privacy…” (M=5.08; SD=.95) and their

“…data security…” (M=4.94; SD=.97) are of highest

priority. Moving to the category Information &

Communication Flow, the results showed a more

differentiated evaluation pattern. Here, the statements

referring to Information Transparency (i.e., “…if I

4,30

4,61

4,75

4,60

4,66

5,08

5,22

4,94

5,19

5,21

5,26

5,38

123456

... if it is ready for the market.

... if it has been thoroughly researched.

... if it has a low error rate.

... if my doctor is well experienced with the technology.

... if my doctor has a good command of the technology.

... if I am well informed about it.

... if I can inform myself well about it.

... if my data security is of the highest priority.

... if my privacy is of highest priority.

... if I can decide who may store my data.

... if I can decide who sees my data.

... if I can decide who may share my data.

Technical

Competence

Professio-

nalism

Information

Transpa-

rency Relevance Data Access

Information & Communication Flow Data Protection

Evaluation (min = 1; max = 6)

rejection agreement

2,86

3,33

4,45

4,35

4,45

4,38

4,77

123456

... if it shows me warmth.

... if it shows me empathy.

... if it is individually tailored to me.

... if it relieves professional caregivers.

... if it relieves my relatives.

... if it improves my health situation.

... if it helps me with activities in everyday life.

Emotional

Aspects

Relief in

Care

Health

Aspects

Evaluation (min = 1; max = 6)

rejection agreement

Associated Trust Criteria

ICT4AWE 2023 - 9th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

130

can inform myself…” (M=5.22; SD=.84) and “…if I

am well informed…” (M=5.08; SD=.91) received the

highest agreement and thus represent relevant factors

for trust in VAAL technology. Further, the statements

referring to Professionalism received agreement, but

at a lower level: “…my doctor has a good command

of…” (M=4.66; SD=1.03) and “…my doctor is well

experienced with…” (M=4.60; SD=1.10) the

technology. Finally, also the items referring to

Technical Competence received agreeing

evaluations: here, participants confirmed statements

referring to “…a low error rate…” (M=4.75; SD=.89)

and “…it has been thoroughly researched” (M=4.61;

SD=1.10)), while the item “…if it is ready for the

market” (M=4.30; SD=1.15) received the lowest, but

still positive evaluations (Figure 1).

Figure 3: Correlations between technology perception and

acceptance (N = 101).

3.2.2 Associated Trust Criteria (RQ2)

The participants also assessed criteria relevant for

trust related to the interaction with VAAL technology

(7 items, Figure 2). Participants evaluated Health

Aspects to be relevant trust criteria when interacting

with VAAL technology. Here, help and support

“…with activities in everyday life” (M=4.77;

SD=1.03) as well as an improvement of the “…health

situation” (M=4.38; SD=1.22) received confirming

evaluations. Likewise, statements referring to Relief

in Care (i.e., relief of “relatives” (M=4.45; SD=1.13)

and “professional caregivers” (M=4.34; SD=1.18)

obtained approval. Regarding Emotional Aspects the

most divergent evaluation patterns were found: the

participants confirmed that if technology “…is

individually tailored” (M=4.45; SD=1.22)

represented a relevant trust criterion for them. In

contrast, the participants tended to reject showing

“empathy” (M=3.33; SD=1.56) and showing

“warmth” (M=2.86; SD=1.46) to be relevant factors

for trust in interacting with VAAL technology.

3.2.3 Relationships Between Technology

Perception & Acceptance (RQ3)

Regarding the relations between technology

perception and the acceptance of VAAL technology

(Figure 3), correlation analyses identified a strong

relationship between the Perceived Benefits and

Acceptance of VAAL technology (ρ=.552; p<.001)

and a moderate negative correlation between

Perceived Barriers and Acceptance (ρ=-.371;

p<.001). A correlation analysis was also run to

uncover relations between Information &

Communication Flow, Data Protection, and

Associated Trust Criteria (Figure 4). The results

showed a direct moderate relationship between

Associated Trust Criteria and the Acceptance of

VAAL technology (ρ=.379; p<.001). Further,

acceptance correlated with the Perceived Benefits of

VAAL technology as well (ρ=.263; p<.001).

However, Trust Criteria were not related with the

other trust constructs (n.s.). Information &

Communication Flow was related with the

Perceived Benefits (ρ=.331; p<.001) and the

Perceived Barriers (ρ=.295; p<.001). Also,

Information & Communication Flow and the

Acceptance of VAAL technology (ρ=.238; p<.001)

were related. Focusing on Data Protection, a

relationship with the Perceived Barriers (ρ=.461;

p<.001) was found. Data Protection was neither

related with the other trust constructs nor with the

Perceived Benefits and Acceptance of VAAL (n.s.).

Figure 4: Correlations between trust and technology acceptance (N = 101).

Acceptance of VAAL

(TAM, 7 Items)

Perceived Barriers

(8 Items)

Perceived Benefits

(7 Items)

.552**

-.371**

Acceptance of VAAL

(TAM, 7 Items)

Perceived Barriers

(8 Items)

Perceived Benefits

(7 Items)

.552**

-.371**

Data Protection

(5 Items)

Information &

Communication Flow

(7 Items)

Trust in AAL Technology

Trust related to

Interaction with

AAL Technology

.238*

.295**

.461**

.331**

.616**

Associated Trust

Criteria

(7 Items)

.379**

.263**

Trust in and Acceptance of Video-based AAL Technologies

131

3.2.4 Role of Trust for Technology

Perception & Acceptance (RQ4)

To answer the underlying research question, linear

regression analyses were run to reveal the role the

technology perception for its acceptance (Figure 5).

39.6% variance of the Acceptance of VAAL

technology (adj. r

2

=.396; F(2,100)=33.77; p<.001)

can be explained by the Perceived Benefits (β=.490;

p<.001) and Perceived Barriers (β=-.350; p<.001).

Figure 5: Regression analysis: Role of technology

perception for acceptance (N = 101).

Next, the three identified trust constructs were

considered in regression analyses as well. Based on

the results of the correlation analysis, linear

regression analyses were conducted. Starting with the

Acceptance of VAAL technology, the regression

model predicted 47.9% (adj. r

2

=.479;

F(2,100)=23.96; p<.001) variance of Acceptance

based on Perceived Benefits (β=.364; p<.001),

Perceived Barriers (β=-.382; p<.001) and the trust

construct Associated Trust Criteria (β=.269;

p<.001). Information & Communication Flow

(β=.146; p=.082; n.s.) was not a predictor for the

Acceptance of VAAL technology. Based on the

results of the correlation analysis, the role of the trust

constructs for the perception of VAAL technology

was analysed (Figure 6: significant results).

For the Perceived Benefits, the regression model

predicts 13.1% variance (adj. r

2

=.131; F(2,100)=8.56;

p<.001) based on the two trust constructs

Information & Communication Flow (β=.260;

p<.01) and Associated Trust Criteria (β=.244;

p<.05). For the Perceived Barriers, the regression

model explained 18.5% variance (adj. r

2

=.185;

F(2,100)=12.32; p<.001) based on the trust construct

Data Protection (β=.391; p<.01). In contrast,

Information & Communication Flow (β=.073;

p=.54; n.s.) was not proven to be a significant

predictor of the perceived barriers of VAAL

technology.

4 DISCUSSION

In this study, a mixed-methods approach was used to

explore the perceptions of VAAL technology on trust

and acceptance.

From the interview study, two main themes

emerged, data protection and information and

communication flow. The category “Data

protection” included relevance and data access.

Information and communication flow consisted of

information transparency, professionalism, and

technical competence. These categories suggest an

interplay of aspects pertaining to the technology itself

and providers that are involved in its usage. In

addition, a separate category covered aspects of

associated trust criteria, consisting of health

aspects, relief in care, and emotional aspects. These

results suggest that there are multiple facets relevant

for trust in VAAL technology. In the subsequent

survey, four research questions in the context of trust

components in VAAL technology and its relation

to acceptance and, specifically, to the benefit and

Figure 6: Regression analysis: Role of trust for technology perception and acceptance (N = 101).

Acceptance of VAAL

(adj. r

2

=.396)

Perceived Barriers

(8 Items)

Perceived Benefits

(7 Items)

.490**

-.350**

Acceptance of VAAL

(adj. r

2

=.479)

Perceived Barriers

(adj. r

2

=.195)

Perceived Benefits

(adj. r

2

=.135)

Data Protection

(5 Items)

Information &

Communication Flow

(7 Items)

Trust in AAL Technology

Trust related to

Interaction with

AAL Technology

.397**

.260**

Associated Trust

Criteria

(7 Items)

.269**

.244**

.364**

-.382**

ICT4AWE 2023 - 9th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

132

barriers perceptions. The role that the trust

dimensions played in the perception and acceptance

of VAAL was identified with regression analyses.

The findings revealed multiple significant

relationships that are discussed in the next section.

Data protection in line with data access and

security was highlighted as extremely trust-relevant

by participants. Regarding information and

communication flow, information transparency was

the most important predictor of trust, followed by

professionalism and technical competence. This

means that there are clear rankings of which factors

are important for trusting VAAL. When it comes to

the question of which trust criteria are applied, there

were more diverse answers. While relief in care and

health aspects are undisputedly trust relevant,

emotional aspects received contradicting evaluations.

Apparently, associated trust criteria vary more among

participants and seem to be more individual.

In line with previous research on the acceptance of

AAL technologies (Peek et al., 2014; Offermann et

al., 2022), the evaluations of the technology are

significantly associated with the overall VAAL

acceptance. The higher benefits were perceived, the

higher was the resulting VAAL acceptance, and also,

higher assessments of perceived barriers lowered this

overall acceptance. Associated trust criteria directly

correlated with perceived benefits and overall

acceptance of VAAL technology. Moreover, data

protection significantly correlated with perceived

barriers, while information and communication flow

was significantly associated with perceived benefits.

Both of these relationships are also associated with

overall acceptance which signals an indirect effect of

trust in VAAL technology through perceptions of

VAAL technology.

With respect to the identified trust constructs, one

trust construct directly and two indirectly correlated

with the acceptance of VAAL technology. In line

with previous research (e.g., Jaschinski, 2018;

Wilkowska & Ziefle, 2019), these results confirm

trust to be a decisive factor for the acceptance of

medical assisting technologies. Beyond that, the

study identified different facets of trust suggesting a

network of influences relating to different constructs.

There are not many studies combining the knowledge

from qualitative and quantitative approaches as

outlined by a review from Peek et al. (2014).

Summarizing the approach and the methodology, we

can say that the mixed-methods design provides a

solid foundation for scientific practice, but also

allows for flexibility and opportunity to extract in-

depth knowledge.

When it comes to the limitations of the study, a

first issue regards the use of “only” scenario-based

evaluations of trust and the acceptance of VAAL. We

cannot exclude that scenario-evaluations differ from

the agreements or rejections and usage behaviours in

real-life contexts, representing the well-known gap

between (reported) attitudes and the (real) behaviour

(Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980). Future studies might

incorporate some sort of scenario comparison that

would allow for an experimental manipulation of the

targeted VAAL systems. It is further relevant to

outline how trust perceptions alter the evaluations of

acceptance as it represents one of the key predictors

of the perception and acceptance including the

intention to use VAAL technology.

Reflecting the sample of the quantitative study, the

size was relatively small, and not very representative

for the majority of people which are in need of care.

Thus, we cannot exclude a sample selection bias,

which reduces the generalizability of our findings to

the whole population of care.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This study used two methodological approaches in

order to investigate trust in VAAL technology and its

relationship with the acceptance of such technologies.

Several dimensions of trust revealed to be relevant in

understanding how people evaluate potential benefits

and barriers, but also, whether the users are more or

less likely to accept such technologies. When

designing these technologies, it becomes evident that

not only the technological features are important to

think about but also the context. Specifically the

interactions of the people involved, such as

technicians, physicians, and healthcare providers, are

important to prepare and honour. It is important to

remember that people still place their trust to a large

extent in humans and by extension, on their

recommendations of said technologies.

Understanding these mechanisms can help in

educating developers, computer scientists, healthcare

professionals and even policy makers about the

priorities of the potential users.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors thank Verena Grouls for research support.

This project has received funding from the European

Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation

Trust in and Acceptance of Video-based AAL Technologies

133

programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant

agreement No 861091.

REFERENCES

Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding Attitudes and

Predicting Social Behavior. 1st ed. Englewood Cliffs,

NJ: Prentice-Hall (1980).

Alshammari, S. H., Rosli, M. S. (2020). A review of

technology acceptance models and theories. Innovative

Teaching and Learning Journal (ITLJ), 4(2), 12-22.

Beier, G. (1999). Kontrollüberzeugungen im Umgang mit

Technik [Locus of control when interacting with

technology]. Report Psychologie, 24(9):684–693.

Bova, C., Fennie, K. P., Watrous, E., Dieckhaus, K., &

Williams, A. B. (2006). The health care relationship

(HCR) trust scale: Development and psychometric

evaluation. Res Nurs Health, 29(5), 477-488.

Climent-Perez, P., Spinsante, S., Mihailidis, A., & Florez-

Revuelta, F. (2020). A review on video-based active

and assisted living technologies for automated

lifelogging. Expert Systems with Applications, 139.

Davis, F. D., 1989. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease

of Use, and User Acceptance of Information

Technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340.

Erquicia, J., Valls, L., Barja, A., Gil, S., Miquel, J., Leal-

Blanquet, J., ... & Vega, D. (2020). Emotional impact

of the Covid-19 pandemic on healthcare workers in one

of the most important infection outbreaks in Europe.

Medicina Clínica,, 155(10), 434-440.

Jaschinski, C. (2018). Independent Aging with the Help of

Smart Technology: Investigating the Acceptance of

Ambient Assisted Living Technologies. Dissertation.

University of Twente.

Jaschinski, C., & Allouch, S. B. (2015). An extended view

on benefits and barriers of ambient assisted living

solutions. International Journal on Advances in Life

Sciences 7(1-2). 40-53.

Jaschinski, C., Allouch, S. B., Peters, O., Cachucho, R., &

Van Dijk, J. A. (2021). Acceptance of technologies

foraging in place: A conceptual model. Journal of

medical Internet research, 23(3),

McKnight, D. H., & Chervany, N. L. (2001). What trust

means in e-commerce customer relationships: An

interdisciplinary conceptual typology. International

Journal of Electronic Commerce, 6(2), 35-59.

Michel, J. P., & Ecarnot, F. (2020). The shortage of skilled

workers in Europe: Its impact on geriatric medicine.

European Geriatric Medicine, 11(3), 345-347.

Offermann-van Heek, J., Schomakers, E. M., & Ziefle, M.

(2019). Bare necessities? How the need for care

modulates the acceptance of ambient assisted living

technologies. International Journal of Medical

Informatics, 127, 147-156.

Offermann, J., Wilkowska, W., Ziefle, M. (2022). Interplay

of Perceptions of Aging, Care, and Technology

Acceptance in Older Age. International Journal of

Human–Computer Interaction, 1-13.

Offermann-van Heek, J., & Ziefle, M. (2019). Nothing else

matters! Trade-offs between perceived benefits and

barriers of AAL technology usage. Frontiers in Public

Health, 7, 134.

Peek, S. T., Wouters, E. J., Van Hoof, J., Luijkx, K. G.,

Boeije, H. R., & Vrijhoef, H. J. (2014). Factors

influencing acceptance of technology for aging in

place: a systematic review. International journal of

medical informatics, 83(4), 235-248.

Qiao, Y., Asan, O., & Montague, E. (2015). Factors

associated with patient trust in electronic health records

used in primary care settings. Health Policy and

Technology, 4(4), 357-363.

Rahimi, B., Nadri, H., Afshar, H. L., Timpka, T., (2018). A

systematic review of the technology acceptance model

in health informatics. Applied clinical informatics, 9(3),

Schomakers, E. M., Biermann, H., & Ziefle, M. (2021).

Users’ Preferences for Smart Home Automation–

Investigating Aspects of Privacy and Trust. Telematics

and Informatics, 64, 101689.

Steinke, F., Fritsch, T., Brem, D., & Simonsen, S. (2012).

Requirement of AAL systems: Older persons' trust in

sensors and characteristics of AAL technologies. In

Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on

Pervasive Technologies Related to Assistive

Environments (pp. 1-6).

Wahezi, S. E., Kohan, L. R., Spektor, B., Brancolini, S.,

Emerick, T., Fronterhouse, J. M., ... & Kaye, A. D.

(2021). Telemedicine and current clinical practice

trends in the COVID-19 pandemic. Best Practice &

Research Clinical Anaesthesiology, 35(3), 307-319.

Wilkowska, W., Offermann-van Heek, J., Florez-Revuelta,

F., & Ziefle, M. (2021). Video cameras for lifelogging

at home: Preferred visualization modes, acceptance,

and privacy perceptions among german and turkish

participants. International Journal of Human–

Computer Interaction 37(15), 1436-1454.

Wilkowska, W., Ziefle, M. (2019). Determinants of Trust

in Acceptance of Medical Assistive Technologies. In:

Bamidis, P., Ziefle, M., Maciaszek, L. (eds). ICT4AWE

2018. Communications in Computer and Information

Science, vol 982. Springer, Cham.

Wilkowska, W., Ziefle, M., & Himmel, S. (2015).

Perceptions of personal privacy in smart home

technologies: Do user assessments vary depending on

the research method?. In International Conference on

Human Aspects of Information Security, Privacy, and

Trust (pp. 592-603). Springer, Cham.

Xu, J., Le, K., Deitermann, A., & Montague, E. (2014).

How different types of users develop trust in

technology: A qualitative analysis of the antecedents of

active and passive user trust in a shared technology.

Applied Ergonomics, 45(6), 1495-1503.

ICT4AWE 2023 - 9th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

134