Digital Transformation of Public Services from the Perception of ICT

Practitioners in a Startup-Based Environment

George Marsicano

a

, Edna Dias Canedo

b

, Glauco V. Pedrosa

c

, Cristiane S. Ramos

d

and Rejane M. da C. Figueiredo

e

University of Brasilia (UnB), Brasilia, Brazil

Keywords:

Digital Transformation, Public Services, Perception of ICT Practitioners, Enterprise Content Management.

Abstract:

In 2021, the Brazilian government created the StartUp GOV.BR program to accelerate the digital transforma-

tion of the public sector in Brazil. Inspired by the business’s culture of startups, this program gathers ICT

practitioners with multiple competencies dedicated to the planning, development and delivery of digital trans-

formation projects. This article aims to investigate and understand the perception of these ICT practitioners

about the StartUps GOV.BR program in order to identify possibilities for improvement. For this, we conducted

23 focus groups with up to 12 people, totaling 175 participants. Then, we fully transcribed and qualitatively

analyzed the data from each of the focus groups based on the Grounded Theory. The results were organized

and structured through the construction of models of relationships between categories, along with narratives

that help to explain and understand the members’ perception of the StartUp GOV.BR program. As results, we

present 34 improvement points and 62 actions to be carried out towards program improvement. The results

achieved in this work can contribute to delineate growth strategies, as well as the assets and capabilities re-

quired in order to successfully transform digitally public services not only in Brazil but also in governments

around the world.

1 INTRODUCTION

The evolution of Information and Communication

Technologies (ICT) has provided numerous relevant

resources for managers in private and public

organizations to rethink their processes and services

(Le

˜

ao and Canedo, 2018). For the public sector,

each service or process integrated into the digital

environment contributes a little more to the efficiency

of the machinery of government. This movement

has been called Digital Transformation, which is

the transition from a conventional, manual and even

inefficient operational model to integrated, agile and

interconnected environments that bring efficiency

and quality to work (Canedo et al., 2020); (Le

˜

ao and

Canedo, 2018); (Pedrosa et al., 2022). Governments

around the world have been very attentive to the

importance of digital transformation (Ines Mergel

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9212-9124

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2159-339X

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5573-6830

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6235-5590

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8243-7924

et al., 2019); (Scupola and Mergel, 2022); (Bravo

et al., 2021). However, for this transformation

to occur, a plan is needed to create procedures,

techniques and tools that improve both planning and

teamwork (Correa et al., 2022).

The implementation of methodologies for

structuring and controlling Digital Transformation

activities is a major challenge for governments

around the world (Gong et al., 2020). In Brazil, one

of the methodologies adopted by the government to

accelerate Digital Transformation was to implement

an innovative program, called StartUp GOV.BR,

which is analogous to the business process known as

a startup. In startups, companies that have recently

begun operation and thus have no operational

history must develop or improve a business model

in a scalable and disruptive way (Bortolini et al.,

2018). In the StartUp GOV.BR program, instead of

companies, services or processes are created using

digital technology and/or other more profitable and

practical solutions towards a more effective and

efficient digital transformation.

The StartUp GOV.BR program was established in

March 2021 by the Digital Government Secretariat

490

Marsicano, G., Canedo, E., Pedrosa, G., Ramos, C. and Figueiredo, R.

Digital Transformation of Public Services from the Perception of ICT Practitioners in a Startup-Based Environment.

DOI: 10.5220/0011826600003467

In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2023) - Volume 2, pages 490-497

ISBN: 978-989-758-648-4; ISSN: 2184-4992

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

(SGD) of the Brazilian Ministry of Economy (ME),

which selects strategic digital transformation projects

that have a high impact on the population and

allocates a group of ICT practitioners dedicated to

the planning, development, and delivery of these

projects. The expertise of the ICT practitioners

covers several areas of knowledge, including project

management, information security, user expertise,

software development and data science. Allocating

this multidisciplinary team aims for meeting the

demands for technological and innovative solutions,

making digital transformation processes more

practical and agile.

This paper aims to investigate and understand

the perception of ICT practitioners (members of

StartUps) about the program after 1 year of its

beginning. For this purpose, we conducted 23

focus groups with up to 12 people, totalling 175

participants. Data from each of the groups were

fully transcribed and analyzed qualitatively based on

Grounded Theory (Carver, 2007).

2 METHODOLOGY

We adopted a methodological process consisting of

four phases: Planning; Data collection; Data analysis

and interpretation; and Writing. The data collection

procedure comprised 23 interviews with focus groups

(Kontio et al., 2004) composed of up to 15 people

that played different roles in several startups. Two

weekly meetings were held to ensure the participation

of at least one startup professional in at least one of

the weekly meetings. The guiding questions were:

Q.1. What is your perception of the StartUp GOV.BR

program?

Q.2. How do you perceive the performance and

internal functioning of the startups?

Q.3. How do you perceive the external context of the

startup?

Q.4. How do you perceive the relationships between

the startup, ME and other organizations?

All meetings were online and lasted up to two

hours. An interview script was followed: 1. First

contact: the facilitator started the meetings by

introducing himself and explaining the purpose and

relevance of the research, as well as the need for

collaboration of the interviewees. The confidentiality

of all the information disclosed during the session

was emphasized. The interviewees also introduced

themselves by telling their name, their background,

and the StartUp they belonged to. 2. Question

formulation: the guiding questions were made one

at a time, and participants were free to speak at will.

Further details were requested when necessary. 3.

Recording of responses: all sessions were transcribed

(with consent from the participants) to ensure greater

accuracy and veracity of the information. 4. Closing:

the interviews were closed cordially.

The principles of Grounded Theory were applied

in the analysis and interpretation of the results.

According to (Carver, 2007), elements of Grounded

Theory can help researchers both in exploratory

studies (to generate hypotheses) and in confirmatory

studies (to identify evidence that does or does not

support the hypotheses). According to (Merriam and

Tisdell, 2016), analyzing data means answering the

research question. This is often conducted through

the coding approach established by (Corbin and

Strauss, 2014), which is divided into three phases: 1)

Open coding: it is performed at the beginning of data

analysis and consists of marking any data unit that

may be relevant to the study and outlining concepts

to represent blocks of raw data. At the same time,

concepts are qualified in terms of their properties

and dimensions (Corbin and Strauss, 2014), (Singer

et al., 2008); 2) Axial coding: it is the process of

relating the categories and subcategories identified in

open coding, refining the category scheme (Corbin

and Strauss, 2014); and 3) Selective coding: it means

to develop the central categories, propositions, or

hypotheses. To do so, the researcher must reflect on

how the categories and their interrelationships can

lead to the development of a model or even a theory

to explain the phenomena (Corbin and Strauss, 2014),

(Seaman, 2008).

Parallel to the three coding phases, three levels of

abstractions were used to organize the data: 1. code,

extracted from raw data; 2. concept, which points

the researcher’s interpretations of a set of codes; and

3. category, a grouping of concepts that allows the

researcher to reduce and combine data. Data were

constantly compared during the analysis. According

to (Merriam and Tisdell, 2016), comparing one data

segment with another helps to determine similarities

and differences between them. The general objective

of constant comparison is to identify patterns in

the data. Patterns are then organized in terms of

relationships with each other in the construction of

the theory (Corbin and Strauss, 2014).

Twenty-three interviews were carried out with

the focus groups from February 2022 to May 2022

with the participation of 175 ICT practitioners.

This sample represents practitioners from all 25

startups of the Startup GOV.BR program and the

7 roles played by them. The focal group sessions

Digital Transformation of Public Services from the Perception of ICT Practitioners in a Startup-Based Environment

491

were held remotely through Microsoft Teams, which

made it possible to connect people from the Federal

District and 13 states of Brazil. The participants

work in different entities of the Brazilian Public

Administration.

Data analysis was performed using Ground

Theory ((Corbin and Strauss, 2014). The codes,

concepts and categories were identified based on

the data collected, avoiding the use of preconceived

logical hypotheses. The entire process of coding was

performed by three authors of this research with the

help of the MAXQDA

1

tool. First, the open coding

of focus groups was done based on the selection

of text segments and the assignment of codes to

them. For each participant of each focus group,

codes were generated that were constantly compared

with each other (within the same focus group and

between focus groups) to identify similarities and

differences and, consequently, patterns in the data

(Merriam and Tisdell, 2016). Furthermore, the

codes were structured iteratively. Three researchers

participated in this coding phase. Thus, every time

the files used by the researchers were unified, the lead

researcher compared the codes created by the two

other researchers for coherence. It is important to

mention that the researchers participated in different

focus groups. Second, the categories were built. The

codes were grouped into concepts, and the concepts

were grouped into categories. As the coding process

took place, a set of relationships between concepts

around categories was identified. Based on this,

narratives were constructed that helped to answer

each of the guiding questions. It is important to

highlight that the entire process of data analysis was

supported by the writing of memorandum, which

helped the researchers to keep their partial records

and their reflections on the codes, concepts and

categories that emerged throughout the research

process (Corbin and Strauss, 2014), (Glaser, 2011).

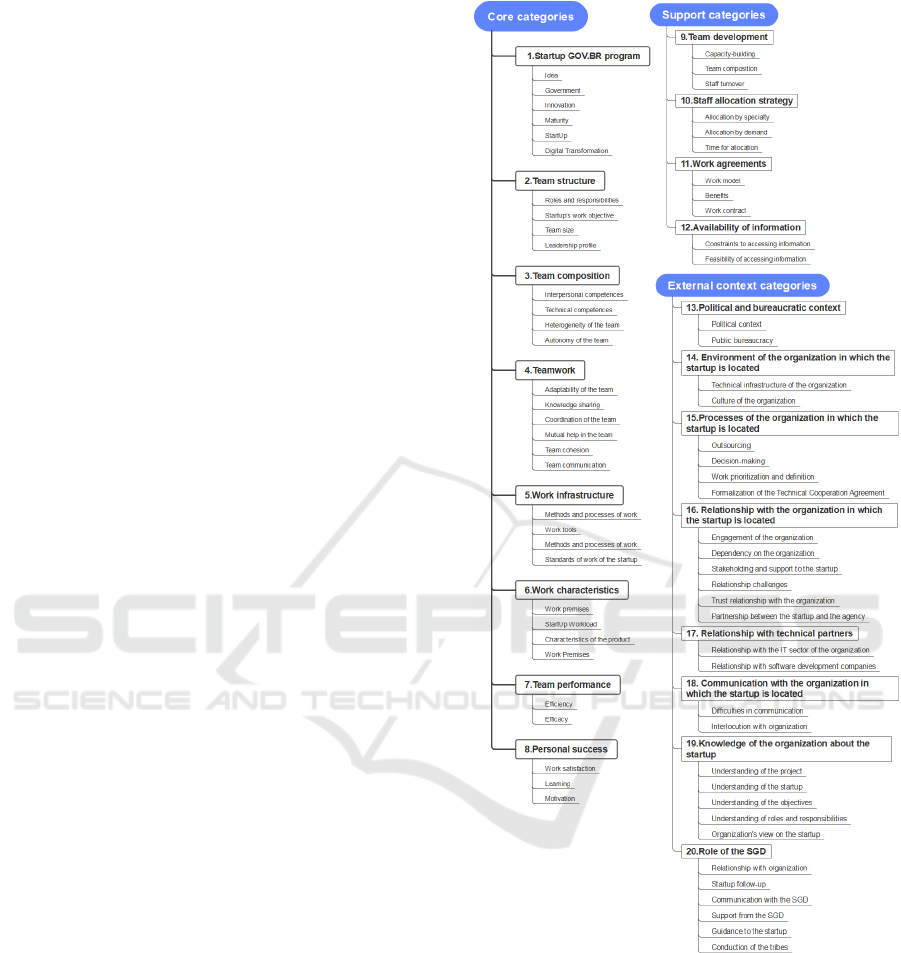

3 RESULTS

The participants’ statements in all focus groups were

transcribed and duly anonymized. This transcription

generated 23 documents with 1,490 coded text

segments, which gave rise to 73 concepts (groupings

of text segments) and 20 categories (groupings of

concepts). In the following, the obtained results

will be presented with a focus on the categories and

the derived concepts, according to the four guiding

questions.

1

https://www.maxqda.com/pt

3.1 Q.1

Q.1 is a broad question related to the perceptions

of ICT practitioners about the StartUp GOV.BR

program. The data that helped to answer this question

are organized within the category ‘StartUp GOV.BR

program’, which is composed of six concepts as

shown in Figure 1. The concepts of the category

‘StartUp GOV.BR program’ are:

• Idea: this concept encompasses data referring

to the practitioners’ perception of the idea of

the StartUp GOV.BR program. Repeatedly, the

evidence points to a shared perception that it is an

‘excellent’, ‘very good’, ‘sensational’, ‘positive’,

‘relevant’ idea. There are also reports on the

scope of the program. Several experts reported

that they had no idea of such scope, which they

see as a very positive thing. Also, some data show

that the idea of the program is revolutionary,

audacious, ambitious and necessary for the

government.

• Government: repeatedly, the evidence indicates

that experts are concerned about the change of

government and the continuity of the StartUp

GOV.BR program. There is a strong consensus

among focus group participants that the program

must be kept independent of the government. In

addition, data indicate that the Brazilian State will

be much more agile and digital as the program

continues in the future.

• Innovation: the data indicate that the innovative

character of the StartUp GOV.BR program is one

of the great motivations and appeals for specialists

to want to take part.

• Maturity: the evidence points to a strong

consensus among specialists that the StartUp

GOV.BR program needs to mature in terms of

its work strategy, allocation of practitioners, and

choice and definition of projects. In addition,

certain amateurism is still reported in the

program, conceding that there is a learning

process for those involved (SGD, startup, partners

organizations) and expecting great perspectives

for the future.

• Startups: the data indicate that practitioners like

the mode of work, structure and organization

of startups, and are excited to see their benefits.

Some data point to startups as a driving force that

enables projects in various government bodies.

Also, some reports register the impossibility of

using agile methodologies, as well as practitioners

frustrated with the difference between the idea

of the StartUp GOV.BR program and the daily

ICEIS 2023 - 25th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

492

experience of startups. The prior preparation

of the startups is considered essential in terms

of planning and business knowledge before

establishing a solution.

• Digital Transformation: this concept concerns

the practitioners’ view of digital transformation

in the government. The evidence points to

two groups of data: 1) Benefits of Digital

Transformation: the most mentioned benefit

is the ease and improvements in the provision

of government services to the citizen. Some

reports point to digital transformation as

a disruptive and evolutionary process. 2)

Barriers to Digital Transformation: bureaucracy

and the government’s need for a change in

mentality are indicated as major barriers to digital

transformation.

The following narrative helps to answer Q.1:

“Specialists believe the StartUp GOV.BR program

is an excellent innovating idea which presents itself

as a great appeal and motivation for practitioners

interested in being part of the startup. The possibility

of facilitating and improving citizens’ lives through

digital transformation is seen as an important benefit

of the program. Practitioners like the startups’

work modes, structure and organization, and are

excited to see the possible results of the program.

Currently, it is understood that the program needs

to mature in terms of its work strategy, allocation

of practitioners, choice and definition of projects.

Finally, practitioners are concerned about the

continuity of the StartUp GOV.BR program as the

government changes. For them, the program must

be kept independent of the government, so that the

Brazilian State can be more agile and digital in the

future.”

3.2 Q.2

To answer Q.2, Q.3 and Q.4, the participants of

the focus groups addressed not only the internal

functioning of the startup but also its external

relations (with the organization in which it is located,

with third parties, and with the Ministry of Economy)

and political and bureaucratic context, work processes

external to the startup, work agreements, etc.–that is,

a set of other aspects that impact the performance and

functioning of startups to a greater or lesser extent.

To support the identification and organization

of the set of categories, concepts and relationships,

we used the models on teamwork proposed by

(Gladstein, 1984), (Cohen, 1993), (Hoegl and

Gemuenden, 2001), (Lindsjørn et al., 2016) and

(Marsicano, 2020). This strategy aims to make sense

of the grouping of code sets into a given concept

and category, thus bringing greater consistency and

meaning to the data, given the complementary use of

empirical data and conceptual models.

To answer Q.2, it is important to highlight that

the internal context of startups means everything that

involves their members (essentially, the practitioners),

their internal relationships, the composition and

structure of the team, their infrastructure and

work characteristics, and their results. The orga-

nization, the work agreements and the availability of

information, which have a direct relationship with the

startup, are also considered part of this context. Thus,

the internal context of the startup has two groups

of categories: core and support. Core categories

are those that relate to a set of essentially internal

characteristics and support categories are those that

refer to a set of characteristics that directly support

the core categories. Figure 1 the concepts of these

two categories. Based on the set of data resulting

from the focus groups (categories, concepts, codes

and models), we present the narrative that helps to

answer Q.2:

“Startups work centered on teamwork, whose inputs

are team design, organization and work agreements.

In team design, startups have a facilitating and

committed leadership, as well as clarity about work

objectives, even though teams are inadequately sized

and lack a proper understanding of their roles and

responsibilities. The teams are made up of mature,

proactive, resilient, heterogeneous people with

technical skills suited to the job. However, startups

lack autonomy. Practitioners face difficulties in being

allocated to activities according to their experience.

When this happens, they feel underutilized and

have an increased need for training courses to

improve their individual performance. The work

agreements need to be clear from the beginning of

the contract and the lack of health insurance and

a career plan, as well as the low salary and the

duration of the contract, are factors that contribute

to weakening the relationship between practitioners

and the StartUp GOV.BR program, increasing the

high turnover rate. On the other hand, remote work

strongly favors the feasibility of startups. According

to practitioners, the team members are aware of the

need for evolution and maturation in the use of agile

approaches, help each other, share their knowledge

and experiences, have fluid communication and

good internal coordination, and have feelings

of belonging and unity. At the individual level,

practitioners report learning (new technologies,

roles, work models), satisfaction, engagement and

commitment to work and deliveries. On the team’s

Digital Transformation of Public Services from the Perception of ICT Practitioners in a Startup-Based Environment

493

side, meeting deadlines is difficult, although there is

satisfaction with the quality generated and the results

produced for society. Regarding teamwork and the

results expected, practitioners mention the lack of an

adequate work infrastructure (tools, processes and

reference methods) and the difficulty to obtain the

necessary information for carrying out the work as

points that make it hard to generate results. This is

enhanced by characteristics such as work overload

and pressure, the need for interaction with different

actors (entities, areas, technical partners), the size

and complexity of the products, and the lack of

compliance with some premises needed for carrying

out the work of startups.”

3.3 Q.3

Q. 3 is related to the perception of ICT practitioners

on the external context of the StartUp GOV.BR

program. The external context is understood as

everything that goes beyond the internal context, that

is, the organization in which the startup is located,

as well as its work processes, structure, political and

bureaucratic context, and partners. Figure 1 shows

the categories of the external context of a startup.

The narrative that helps to answer Q.3 is:

“Practitioners perceive the external context of

a startup as the context of the organization in

which it is located, encompassing the political and

bureaucratic scenario, the environment (culture and

technical infrastructure) and the work processes; the

relations and communication between the startup,

the organization and technical partners; and the

organization’s knowledge and understanding about

the startup. According to the specialists, the political

instability, the vertical and segmented structures of

the organizations, a non-agile culture, the lack of an

adequate technical infrastructure, the delay in hiring

public or private software factories and in signing

Technical Cooperation Agreements are obstacles for

the startups to carry out their work. When looking

at the startup’s relationship with the organization

in which it is located, although there is support and

sponsorship from the top management, startups are

viewed with distrust in the beginning. Over time, it is

possible to establish a good (enriching) partnership

between startup and organization, although some

are more resistant to it. Specialists also feel a lack

of engagement from in-house servants and business

areas with the project that is being developed.

Associated with this and the lack of knowledge

about the organization, the greatest difficulty for

startups is in identifying and/or having access to

people with whom they must have a technical or

business relationship. Regarding the relationship

between startups and technical partners, there is

a lack of alignment and integration between the

startup and the IT of the organizations; therefore,

the relationship with public or private third parties

tends to be difficult, conflicting and/or limiting. The

communication with the organizations has some

noise, which tend to be solved due to the good

inter-locution carried out by the project managers.

Finally, some organizations lack knowledge about

what the startup is, its projects, objectives, roles,

and responsibilities; startups are sometimes seen as

inspection and audit teams, and specialists as are

seen as outsourced.”

3.4 Q.4

Q.4 is the work of the SGD (institution coordinating

the program) and its relations with startups and

organizations involved in projects of digital trans-

formation. Based on the qualitative analysis of the

focus groups, we defined one category (‘Role of the

SGD’) and we identified six concepts, as shown in

Figure 1. The narrative that helps to answer Q.4 is:

“For practitioners, although there is a feeling

of satisfaction with the individual and collective

support that the SGD offers to startups, problems

are mentioned regarding the (inadequate and slow)

allocation of personnel and the communication

between the startup and the SGD, which is sometimes

seen as stressful and lacking proper disclosure of

projects, technologies, tools and standards that can

be used or serve as a reference by startups day to

day. There is a lack of guidance from the SGD,

especially during the startup formation and the

beginning of work. Regarding the monitoring of the

work, some participants of the focus groups believe

it makes no sense to compare and rank the startups

because their projects differ in nature and their

contexts are unique. In addition, an incongruity is

pointed out regarding the requirement for long-term

planning, since startups are required to act based

on agile methodologies. Concerning the practices

implemented by the SGD, the specialists wish the

meetings of tribes were carried out separately to

discuss more technical topics. Finally, concerning

the relationship between the SGD and the partner

organizations, specialists believe there is a lack of

communication, proximity, alignment and knowledge

about what happens in the organizations and in

the startups day-to-day.” Figure 1 presents the 20

categories and the 73 concepts identified during the

qualitative analysis of the data.

ICEIS 2023 - 25th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

494

4 DISCUSSIONS

In the StartUp GOV.BR program, the initial idea

is that the StartUp teams are oriented towards

agility, based on the following premises: cross-

functional teams, working from end to end, using

agile approaches, and making quick and frequent

deliveries. With regard to cross-functional teams,

the temporary hiring model favored the construction

of teams of specialists. However, the lack of one

or another specialist causes the non-completion of a

set of activities, for example. From an agile point

of view, cross-functional teams should be made up

of people capable of performing multiple roles, not

just specialized roles (data science, developer, UX,

etc.). Even for the formation of teams with several

specialists, StartUps suffer from a lack of human

resources (quantity and skills). For example, there

are teams with only a manager, a process analyst,

and a data scientist. In addition, a group of junior

professionals is identified, or those looking to change

careers, and make StartUp their first experience.

The idea of end-to-end work is for StartUp to

be able to carry out all the work until the delivery

of the software solution to the customer. During

this research, some barriers to end-to-end work

were identified: professional profile restrictions

(inadequate skills or quantities); software product

development policy of some public Institutions that

hinder or prevent StartUps end-to-end work; and

in many cases, StartUps began to relate beyond

the SGD and its public Institution, with technical

partners (public or private), thus losing their ability to

act from end to end. In this scenario, a set of StartUps

has acted only as a kind of project relationship and

follow-up team, which: helps to establish the scope,

performs the planning and follow-up of the project,

identifies high-level requirements and, in some

cases, builds prototypes, and sends them to technical

partners (public or private), who will, in fact, build

the software solutions.

On using agile approaches, what gives support

and meaning to the use of agile practices are their

values and principles. If these values and principles

are weakened, then practices tend to become

inefficient. In some cases, this is the scenario of

StartUps. To overcome this drawback, each StartUp

tries to use one or another agile practice that can

facilitate their work but also has to maintain practices

and/or artifacts of plan-driven approaches.

Difficulties in adopting agile approaches in

the StartUp GOV.BR Program causes: fragility in

sustaining agile values and principles; the lack of

knowledge and experience, from top management to

Figure 1: Categories and concepts of the internal and

external contexts of startups.

the technical level; vertical structures and difficult

communication; the need for command and control,

with the requirement of long-term planning; the

political environment of public Institutions, which

sometimes makes decisions to the detriment of the

technical context; treatment of requirements as fixed

or stable from the beginning of the project (in some

cases); the resistance from a non-agile culture on

the part of some public Institutions. Given all this

context, making quick and frequent deliveries also

Digital Transformation of Public Services from the Perception of ICT Practitioners in a Startup-Based Environment

495

becomes a major challenge for StartUps. The culture

of some public institutions makes it difficult to carry

out small partial deliveries, favoring the delivery of

large scopes over a longer period of time. On the

other hand, it is still possible to identify a set of

public institutions that are favorable and support the

implementation of an agile culture in their internal

processes. Which favors part of the StartUps in

carrying out fast and frequent deliveries.

Faced with so many challenges and possibilities

related to the StartUp GOV.BR program, we proposed

34 points for improvement and 62 actions in order to

help to maximize the generation of results, to mature

the program, as well as to define strategies for the

coming years. Each point of improvement and action

was related to one or more categories and concepts

identified in the data analysis process. In addition, for

each action, those responsible for its execution, the

target public, and its possible impacts are identified.

5 THREATS TO VALIDITY

To increase internal validity, we performed data

triangulation using (i) multiple methods and

(ii) multiple data sources. Concerning (i), data

was collected through complementary methods:

interviews, document analysis and questionnaire

(Easterbrook et al., 2008), (Merriam, 2009),

(Creswell, 2017). Regarding (ii), data were collected

longitudinally with the same people, but with

different roles and perspectives (Merriam, 2009).

Another strategy adopted was member checking

(Merriam, 2009), in which some participants gave

feedback on the emerging results.

In qualitative research, the most important

question is whether it was supported by data collected

without bias from the researchers. To minimize this

threat, field journals were kept which can be verified

by external auditors. Regarding external validity,

the results of this study will be transferable rather

than generalizable. To improve transferability, the

“rich, thick description” strategy was used (Merriam,

2009) to provide a detailed description to the reader,

enabling them to replicate the study and verify

whether the results of the original study can be

transferred (Merriam, 2009). In addition, we used

the maximum variation strategy, in which teams were

selected randomly to achieve greater diversity and

allow a greater range of applications of the results of

this research.

6 CONCLUSIONS

This paper presented an analysis of the data collected

from 23 interviews with professionals participating

in the StartUp GOV.BR program. According

to the perception of ICT practitioners, building

multi-functional teams to work on projects that

use agile methodologies, which aim to generate

quick and frequent deliveries, had difficulties in

finding a friendly work environment. Startups

suffer from a lack of qualified human resources

to compose cross-functional teams. The general

shortage of software development profiles skilled

in requirements, construction and testing imposes

technical restrictions on startups. There is also a

lack of UX professionals, which limits the ability

of startups to act from the point of view of user

experience. Practitioners reported that their startup

teams were composed only of project managers,

process analysts, and an infrastructure and/or data

science profile.

Regarding the profile of temporary practitioners,

it was reported that hiring generalist professionals

instead of specialists may be more appropriate within

the work context of startups. In other words, it may

be better to hire professionals who have multiple

knowledge, or even to define a mixed contract,

involving specialists and generalists, to provide

greater flexibility in the allocation and work of these

practitioners in the phases of the life cycle. About

startups working end-to-end on their projects, the

restrictions of professional profiles, combined with

the policy of some organizations on the development

of software products, need to be improved. In

many cases, startups began to relate with technical

(public or private) partners, besides the SGD and the

organization. Thus, they lost the possibility to work

end-to-end. Currently, a set of startups act as a kind

of project relationship and follow-up team—they

help to establish the scope, do the planning, identify

high-level requirements, in some cases even build

prototypes, and pass the material on to third parties

and/or private software factories that will actually

build the solutions.

Regarding fast and frequent deliveries, the culture

of some organizations makes it difficult to make

small partial deliveries, favoring the delivery of large

scopes in a deadline longer than six months. Despite

this, some startups have managed to make smaller

deliveries. This needs to be carried out little by little,

gaining the trust of the customer who is unfamiliar

with a culture of agile deliveries and is used to

receiving large systems at once.

ICEIS 2023 - 25th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

496

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work has been supported by Minist

´

erio da

Economia (ME) - Secretaria de Governo Digital

(SGD) Transformac¸

˜

ao Digital de Servic¸os P

´

ublicos

do Governo Brasileiro.

REFERENCES

Bortolini, R. F., Cortimiglia, M. N., de Moura

Ferreira Danilevicz, A., and Ghezzi, A. (2018).

Lean startup: a comprehensive historical review.

Management Decision, 59(8):1765–1783.

Bravo, J., Aquino, J., Alarc

´

on, R., and Germ

´

an, N.

(2021). Model of sustainable digital transformation

focused on organizational and technological culture

for academic management in public higher education.

In Proceedings of the 5th Brazilian Technology

Symposium, pages 483–491. Springer.

Canedo, E. D., Le

˜

ao, H. A. T., and Cerqueira, A. J. (2020).

Citizen’s perception of public services digitization and

automation. In Filipe, J., Smialek, M., Brodsky, A.,

and Hammoudi, S., editors, Proceedings of the 22nd

International Conference on Enterprise Information

Systems, ICEIS 2020, Prague, Czech Republic, May

5-7, 2020, Volume 2, pages 754–761. SCITEPRESS.

Carver, J. (2007). The use of grounded theory in

empirical software engineering. In Empirical

Software Engineering Issues. Critical Assessment and

Future Directions, pages 42–42. Springer.

Cohen, S. G. (1993). Designing effective self-managing

work teams. Center for Effective Organizations,

School of Business Administration . . . .

Corbin, J. and Strauss, A. (2014). Basics of qualitative

research: Techniques and procedures for developing

grounded theory. Sage publications.

Correa, W. A. R., Iwama, G. Y., Gomes, M. M. F., Pedrosa,

G. V., da Silva, W. C. M. P., and da C. Figueiredo,

R. M. (2022). Evaluating the impact of trust

in government on satisfaction with public services.

In Electronic Government - 21st IFIP WG 8.5

International Conference, EGOV 2022, Link

¨

oping,

Sweden, September 6-8, 2022, Proceedings, volume

13391 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages

3–14. Springer.

Creswell, J. W. (2017). Research design: Qualitative,

quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage

publications.

Easterbrook, S., Singer, J., Storey, M.-A., and Damian,

D. (2008). Selecting empirical methods for software

engineering research. In Guide to advanced empirical

software engineering, pages 285–311. Springer.

Gladstein, D. L. (1984). Groups in context: A model of task

group effectiveness. Administrative science quarterly,

pages 499–517.

Glaser, B. G. (2011). Getting out of the data: Grounded

theory conceptualization. Sociology press.

Gong, Y., Yang, J., and Shi, X. (2020). Towards

a comprehensive understanding of digital

transformation in government: Analysis of flexibility

and enterprise architecture. Government Information

Quarterly, 37(3):101487.

Hoegl, M. and Gemuenden, H. G. (2001). Teamwork

quality and the success of innovative projects:

A theoretical concept and empirical evidence.

Organization science, 12(4):435–449.

Ines Mergel, Noella Edelmann, and Nathalie Haug (2019).

Defining digital transformation: Results from expert

interviews. Government Information Quarterly,

36(4):101385. Publisher: JAI.

Kontio, J., Lehtola, L., and Bragge, J. (2004). Using

the focus group method in software engineering:

obtaining practitioner and user experiences. In

Empirical Software Engineering, 2004. ISESE’04.

Proceedings. 2004 International Symposium on,

pages 271–280. IEEE.

Le

˜

ao, H. A. T. and Canedo, E. D. (2018). Best practices and

methodologies to promote the digitization of public

services citizen-driven: A systematic literature review.

Inf., 9(8):197.

Lindsjørn, Y., Sjøberg, D. I., Dingsøyr, T., Bergersen, G. R.,

and Dyb

˚

a, T. (2016). Teamwork quality and project

success in software development: A survey of agile

development teams. Journal of Systems and Software,

122:274–286.

Marsicano, G. M. (2020). Construc¸

˜

ao e validac¸

˜

ao de um

modelo de efetividade de equipes de software. UFPE,

Brazil.

Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative Research and

Case Study Applications in Education. Revised and

Expanded from” Case Study Research in Education.”.

ERIC.

Merriam, S. B. and Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative

research: A guide to design and implementation. John

Wiley & Sons.

Pedrosa, G. V., Judice, A., Judice, M., Ara

´

ujo, L., Fleury,

F., and Figueiredo, R. (2022). Applying user-

centered design on digital transformation of public

services: A case study in brazil. In Hagen, L.,

Solvak, M., and Hwang, S., editors, dg.o 2022:

The 23rd Annual International Conference on Digital

Government Research, Virtual Event, Republic of

Korea, June 15 - 17, 2022, pages 372–379. ACM.

Scupola, A. and Mergel, I. (2022). Co-production in digital

transformation of public administration and public

value creation: The case of denmark. Gov. Inf. Q.,

39(1):101650.

Seaman, C. B. (2008). Qualitative methods. In Guide to

advanced empirical software engineering, pages 35–

62. Springer.

Singer, J., Sim, S. E., and Lethbridge, T. C. (2008).

Software engineering data collection for field

studies. In Guide to Advanced Empirical Software

Engineering, pages 9–34. Springer.

Digital Transformation of Public Services from the Perception of ICT Practitioners in a Startup-Based Environment

497