Introducing Digital Education as a Mandatory Subject: The Struggle of

the Implementation of a New Curriculum in Austria

Corinna H

¨

ormann

a

, Eva Schmidthaler

b

and Barbara Sabitzer

c

STEM Didactics, Johannes Kepler University, Altenbergerstraße 68, Linz, Austria

Keywords:

Digital Education, 21st Century Skills, Computational Thinking, STEM.

Abstract:

In response to the requirement that every European citizen acquires the skills necessary for enhancing and

utilizing digital technology in a critical, inventive, and creative way, the European Digital Competence Frame-

work for the Digital Competence of Educators (DigCompEdu) was developed. In Austria, grade 9 students

began taking “Computer Science” in 1985. For a very long time, there was only this single year of IT edu-

cation that was compulsory during the educational career. 21st century skills were finally formally integrated

into higher grades when Austria introduced the mandatory curriculum “Digital Education” (Digitale Grund-

bildung) in September 2018 for all students in lower secondary education. The administration of the school

could decide whether to provide “Digital Education” as a standalone course or whether to integrate it into

other subjects. Finally, the new curriculum was added to the regular timetable as a compulsory subject in the

2022/2023 academic year. But because of a staffing shortage and a lack of teaching material, schools continue

to struggle with the issue of who is teaching what and how. This paper discusses the introduction of the new

curriculum and examines early results of a poll that 673 teachers participated in between September and De-

cember 2022.

1 INTRODUCTION

Digital technology is usually applied in education

for data collection, administrative efficiency enhance-

ment, and testing rather than teaching. Buckingham

(2020) states that many teachers teach with or through

technology, rather about it. Moreover, educational

technology often fails to bridge everyday students’

lives with what they learn in school (Buckingham,

2020). However, as new professions are emerging, fu-

ture adults will need new abilities and qualifications.

In order to adequately prepare today’s children for the

demanding challenges of the next digital era, the edu-

cational community must move quickly.

The development of pupils’ digital abilities is ex-

tremely important, particularly in the years of the

COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent emergency

remote teaching. Dealing with the pandemic has

posed new issues for the educational sector because

remote learning is sometimes stigmatized as being

less beneficial to academic progress. It is hardly

surprising that throughout the COVID crisis, there

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4770-6217

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9633-8855

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1304-6863

has been an increase in young people’s media use

(Langmeyer et al., 2020). However, the loss of rigid

frameworks from daily school life as a result of the

pandemic has not only had negative effects but has

also significantly increased creativity and digitization,

proving the value of digital education. Nevertheless,

in 2018 the “Teaching and Learning International Sur-

vey” (TALIS) revealed that Austrian teachers show

less professional IT education than educators in other

European countries. Additionally, compared to other

states, Austrian teachers tend to attend fewer digi-

tal education training programs, and information and

communications technologies (ICT) are used less fre-

quently for project work or customized education pro-

grams. Austrian educators’ lack of motivation to use

new technologies is another flaw in international com-

parisons (Sturm, 2020).

The introduction of “Digital Education” as a

stand-alone topic or integrated into other lower sec-

ondary school subjects was the next significant devel-

opment in Austria to address these challenges after

Computer Science was introduced in the 9th grade

in 1985. The subject “Digital Education” became a

mandatory subject for students in grades five to seven

in 2022, and teachers should get extensive additional

Hörmann, C., Schmidthaler, E. and Sabitzer, B.

Introducing Digital Education as a Mandatory Subject: The Struggle of the Implementation of a New Curriculum in Austria.

DOI: 10.5220/0011837000003470

In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2023) - Volume 2, pages 213-220

ISBN: 978-989-758-641-5; ISSN: 2184-5026

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

213

training. Year eight will follow the consecutive year.

However, schools continue to struggle with the prob-

lem of who is teaching what, and how due to a staffing

shortfall and a lack of instructional materials.

This paper describes the theoretical background of

“Digital Education” in Europe with a focus on Aus-

tria. It also addresses the implementation of the new

curriculum and looks at preliminary findings from a

survey that 673 Austrian secondary teachers took be-

tween September and December 2022.

2 THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

2.1 Digital Education in Europe

The Joint Research Center of the European Union de-

fines “Digital Competence” as the following (Ferrari,

2013):

Digital Competence is the set of knowl-

edge, skills, attitudes (thus including abili-

ties, strategies, values and awareness) that are

required when using ICT and digital media

to perform tasks; solve problems; communi-

cate; manage information; collaborate; create

and share content; and build knowledge ef-

fectively, efficiently, appropriately, critically,

creatively, autonomously, flexibly, ethically,

reflectively for work, leisure, participation,

learning, socialising, consuming, and empow-

erment.

Every European citizen must acquire these skills

in order to use digital technology critically and cre-

atively, and the European Digital Competence Frame-

work (DigCompEdu) addresses this need. It offers

a framework for comprehending what it means to be

digitally competent and provides a solid base that can

inform policies in many nations (Redecker and Punie,

2017).

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic the European

Commission released a “Digital Education Action

Plan (DEAP)” in September 2020 to influence the

path that European education should take. Two rele-

vant strategies were proposed: Strategy (1) defines the

technical part of the plan and concentrates on digital

infrastructure and the provision of equipment. Addi-

tionally, it nurtures teachers’ required digital abilities.

Area (2) provides digital education, including the un-

derstanding of new technologies. The main objective

of the program is to update educational systems and

adapt them to recent significant digital advancements.

Reports show that there are serious structural biases

across the EU member states. Only 35% of primary

schools show a reliable infrastructure, whereas 52%

and 72% of lower and higher secondary schools are

considered well equipped (Kask and Feller, 2021).

In Austria’s bordering country Switzerland a

project called “Lehrplan 21” has been developed to

implement the topic “Media and Computer Science”

throughout the school career. The project concen-

trates on “Understanding Media & Responsible Us-

age”, “Basic Computer Science Concepts and Prob-

lem Solving”, as well as “Applied Computer Science”

(Grandl and Ebner, 2017).

According to a 2010 research by the Dresden Uni-

versity, twelve of Germany’s 16 states have media lit-

eracy or fundamental computer science ideas included

in their curricula. But otherwise there is no nation-

wide directive for teaching computer science or digi-

tal education (Grandl and Ebner, 2017).

After giving every student in Great Britain a BBC

micro:bit when they turned eleven or twelve in 2014,

the country added “Information and Communication

Technology” as a required subject. Educational and

teaching objectives concentrate on “Computer Sci-

ence”, “Digital Literacy”, and “Information Technol-

ogy” (Grandl and Ebner, 2017).

Moreover, Slovakia installed the subject “Infor-

matika” for all students from grade two to eleven

by focusing on computational thinking (Grandl and

Ebner, 2017).

Poland’s curriculum now includes lessons on “Un-

derstanding and Analysis of Problems” and “Pro-

gramming and Problem Solving by Using Computers

and other Digital Devices” (Grandl and Ebner, 2017).

Of course, the EU may only give suggestions and

has limited capacities as each member is responsible

for its own system. The European Union can still offer

guidelines for member state coordination, though.

2.2 Digital Education in Austria

Three sub-projects were presented in the Austrian

government’s “Masterplan for Digitalization”, which

was published in 2018. The first sub-project, titled

“Teaching and Learning Content”, focuses on updat-

ing current curricula – however, digital content must

be included. Additionally, it establishes the subject

of “Digital Education” and regulates the creation and

acquisition of digital teaching and learning resources

for classrooms. The second sub-project defines the

concept of “Teacher Training and Teacher Educa-

tion”. The third section of the master plan, “Infras-

tructure and Modern School Administration”, helps in

increasing technological infrastructure, installing dig-

ital devices (both technical and administrative), and

optimizing school administration through the use of

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

214

practice-oriented tools and programs.

The master-plan also presented an 8-point-

concept to foster digital education that is outlined as

the following (Bundesministerium f

¨

ur Bildung, Wis-

senschaft und Forschung, 2018):

1. “Portal Digital School”: should be a single point

of entry and should unify all necessary pedagogi-

cal and administrative applications

2. Standardization of learning platforms

3. Teacher training concerning distance- and

blended learning

4. Expansion of the platform “Eduthek”: this learn-

ing platform provides additional exercises and has

been further developed since the COVID-19 pan-

demic

5. Development of verified learning-apps

6. Upgrading IT infrastructure

7. Supplying students with digital devices

8. Supplying teachers with digital devices

2.2.1 Implementation of “Digital Education” in

2018

In lower secondary education (grades five to eight),

the new topic “Digital Education” was introduced in

September 2018 and has been taught in two to four

hours per week. Schools had to use money from

the school budget to implement more than those four

hours. Futhermore, school administration could de-

cide if they offer stand-alone subjects or if they imple-

ment the curriculum in an integrative way in several

other subjects (Bundesministerium, BMBWF, 2018).

The 2018 curriculum’s eight subject-specific top-

ics were described as follows (BGBLA, 2018):

1. Social aspects of digitalization: reflecting the us-

age of digital devices in everyday life as well as

benefits and ethical boundaries

2. Information, data, & media: queries, evaluating

sources, sharing information

3. Operating systems & standard software: basic

knowledge of operating systems, text processing,

presentation software, calculations

4. Media design: adopting, producing, and adapting

media

5. Communication & social media: different com-

munication platforms, creating digital identities,

cloud-sharing

6. Data security & privacy: securing devices as well

as private data

7. Technical problem solving: solving basic IT prob-

lems

8. Computational thinking: working with algo-

rithms, creative usage of programming languages

2.2.2 Implementation of “Digital Education” in

2022

Heinz Faßmann, the Austrian minister of education,

announced in November 2021 that “Digital Edu-

cation” would become a mandatory subject in the

2022/2023 academic year. Besides, the major differ-

ence is that from 2018 to 2021 students were solely

graded with “successfully completed” or “not suc-

cessfully completed”, whereas now they will receive

traditional grades in five stages from “very good”

to “inadequate” when completing the subject “Dig-

ital Education”. Starting with the academic year

2022/2023, the new model for the subject “Digital

Education” proposes to implement one annual stand-

alone hour peer week for students in grades five to

seven. Grade eight will follow the consecutive year.

Beginning with the school year 2023/2024, the new

competence-oriented curriculum will be implemented

at both primary level and secondary level I, and as

a result “Digital Education” will be made mandatory

for all students. In addition, the new curriculum in-

troduces the overarching topics “IT education” and

“media education” starting with the first grade and

their mandatory implementation in other lessons (Po-

laschek, 2022).

A draft of the new curriculum for “Digital Edu-

cation” was created by a group of experts from uni-

versities as well as teacher training programs, apply-

ing both national and international competency mod-

els (Polaschek, 2022). In March 2022 the concepts

of the new curriculum were presented by the Austrian

Ministry of Education by implementing the 4C’s of

the 21st century: Critical Thinking, Creativity, Col-

laboration, and Communication (BMBWF, 2022).

A two dimensional competence model forms the

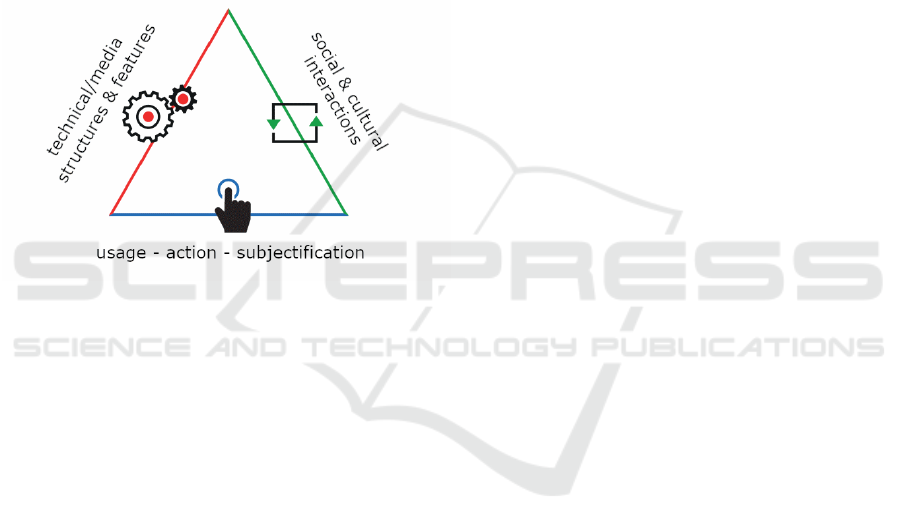

basis of the presented curriculum (see Figure 1)

(BMBWF, 2022):

Figure 1: Competence Model of Austrian Curriculum “Dig-

ital Education” (adapted by the authors) (BMBWF, 2022).

The vertical classification lists the topics repre-

sented in the “Frankfurt Dreieck” (see Figure 2) by

their respective subject headings: (T) technical-media

Introducing Digital Education as a Mandatory Subject: The Struggle of the Implementation of a New Curriculum in Austria

215

– structures and features of digital, IT, and media sys-

tems, (G) social-cultural – social interactions through

the use of digital technologies, and (I) interaction-

related – interaction in the form of usage, action, and

subjectification (Brinda et al., 2019). The horizon-

tal line is formed by the following competencies: (1)

orientation – analyzing and reflecting about social as-

pects of media change and digitization, (2) informa-

tion – responsible handling of data, information, and

information systems, (3) communication – communi-

cating and cooperating using media systems, (4) pro-

duction – creating and publishing digital content, de-

signing algorithms, and creating software programs,

(5) interaction – responsible use of offers and options

of a digital world (BMBWF, 2022).

Figure 2: Frankfurt Dreieck (adapted by the authors)

(BMBWF, 2022).

The curriculum’s content itself is subdivided into

the four grades (Informatikportal AHS

¨

Osterreich,

2022):

5

th

grade:

(T) input–process–output (IPO) model; search en-

gines; protection and usage of personal data; algo-

rithms; hardware components

(G) digital vs. analog; personalized search rou-

tines; online cooperation & collaboration; different

forms of presentation of content; forms of media use

in media change

(I) analyzing and questioning personal usage be-

haviour; conduct internet research; assess quality of

sources; store, copy, search, retrieve, change, and

delete data; perform simple calculations with data;

collect and represent data; text processing; presenta-

tions; use help-systems to solve problems

6

th

grade:

(T) accessibility and usability of technology; col-

lect, filter, sort, interpret, and represent data; how the

internet works; create simple code; hardware vs. soft-

ware; basics of networks

(G) interests and conditions of media production;

selecting and operating suitable software programs;

different communication media; opinion formation

and manipulation; intellectual property rights & copy-

rights; digital communication to participate in social

discourse

(I) digital vs. analog life; license mod-

els; social media; create, adapt, and analyze vi-

sual/audiovisual/auditory content; balance of digital

offers and own needs; health and ecological aspects

7

th

grade:

(T) interdisciplinary examples of applications of

technology in environment and society; artificial in-

telligence; cloud-based systems; use Computational

Thinking to solve problems; computer systems in ev-

eryday objects

(G) changes of media usage behaviour; personal-

ized search routines; compromise between publica-

tion of information and confidentiality and security;

popular media culture; ecological problem constella-

tion in connection with digitization

(I) reflect on digital technologies of everyday life;

searching for information and data using appropriate

strategies; identification of patterns in data represen-

tations to make predictions; use data to show cause

and effect relationships; crowd-sourcing; designing

digital identities in a reflective way; accessibility of

digital content; adapting software applications to per-

sonal needs; viruses or malicious software/malware

8

th

grade:

(T) reflecting on the limits and possibilities of ar-

tificial intelligence; data backup; network protocols;

software development; differences of application soft-

ware, system software, and hardware layers; encryp-

tion software

(G) euphoric and culturally pessimistic attitudes

towards digitalization; collection, evaluation, and

linking of user data in terms of negligence, misuse,

and surveillance; data manipulation; different ways

of displaying content; digital communication to civil

society participation and commitment

(I) normativity of digital technologies and me-

dia content; updating and improving information and

content; communicating responsibly; right to your

own picture; creating simple programs or web appli-

cations; reflecting limits of technical configurations;

precautions for independence and informational self-

determination

In order to prepare students for successful jobs

when they enter the profession, educators should

assist them in acquiring these skills (Connections

Academy, 2013). Therefore, various teacher train-

ing courses started in autumn 2022, to help teachers

tackle the unfamiliar new curriculum. Most of those

courses take up four semesters and are divided into

five modules, which contain, connect, and link media

design processes, IT basics, and media design actions.

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

216

It is meant for educators who actually teach the sub-

ject “Digital Education” as part of their teaching du-

ties or who teach this topic in an integrative manner

(PH Ober

¨

osterreich, 2022).

3 STUDY

3.1 Methodology

The study focused on the implementation of the

mandatory curriculum “Digital Education”, which

was installed in Austria in September 2022. The sur-

vey’s foundation is laid forth in the following research

questions: (RQ1) Which type of implementation of

the curriculum “Digital Education” preferred teach-

ers: integrated or stand-alone? (RQ2) Are there any

topics of the curriculum teachers struggle with? If so,

which?

The survey was distributed to all Austrian sec-

ondary public schools to teachers who actually

teach “Digital Education” in the current school year

2022/23. A total of 795 teachers agreed to begin the

questionnaire, whereas 673 managed to finish it.

First, it was verified that the participants actually

teach “Digital Education” in the current school year,

to sort out all other teachers. The second part of the

survey concerned gender, age group, years in service,

school type, and subjects taught.

The next section focused on the teacher training

course “Digital Education” and consisted of the fol-

lowing questions:

1. Are you currently attending the teacher training

course for “Digital Education”? (yes/no)

2. If no at (1): Are you planning to attend such a

course in the future? (yes/maybe/no)

3. If no at (2): Why is such a course out of the ques-

tion for you? (no time/I already know everything

about it/no interest/too much work/not supported

by the school/other)

The last section was dedicated to personal encoun-

ters of the teachers. The following questions were

implemented by using a scale-rating applying a five-

point Likert scale with the options “strongly agree,

agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, strongly

disagree” (Joshi et al., 2015).

Please rate the following statements:

1. I think the content of the curriculum for the sub-

ject “Digital Education” makes sense.

2. I think the introduction of the subject “Digital Ed-

ucation” as an independent subject makes sense.

3. I think it was better when “Digital Education”

could still be integrated into other subjects.

4. I am having troubles preparing for “Digital Edu-

cation” class.

5. I have sufficient resources to prepare for lessons

in “Digital Education”.

6. I feel confident in terms of content in “Digital Ed-

ucation” class.

7. I think that “Digital Education” should be taught

by teachers who studied computer science.

Succeeding questions also used a five-point Likert

scale with the options “very good, good, intermediate,

poor, very poor” (Joshi et al., 2015).

Please rate your knowledge in the individual com-

petence areas of the “Digital Education” curriculum

based on school grades:

1. analyzing and reflecting on social aspects of me-

dia change and digitization

2. handle data, information, and information sys-

tems responsibly

3. communicating and cooperating using IT systems

4. creating and publishing content digitally, design-

ing algorithms, and programming

5. assess offers and options for a world shaped by

digitization and use them responsibly

The next questions concerned possible support:

1. Would you like to have more support in imple-

menting the “Digital Education” curriculum?

2. If yes at (1): Which offers would you use?

(teacher training at universities/teacher train-

ing at school/online teacher training/online re-

sources/books/other)

Moreover, an opportunity was provided to add

personal opinion by asking “I would also like to say

the following”. Still, this paper concentrates on eval-

uating the quantitative survey data, while the qualita-

tive survey data are reviewed in other articles.

3.2 Results

In total there were 795 participants, whereas 673 suc-

cessfully completed the questionnaire. Four-hundred-

fifty-four (67.5%) of those who finished the survey

claimed that they actually teach “Digital Education”.

3.2.1 General Information Results

Of the 454 teachers, 309 (68.1%) stated that they are

“female”, 138 (30.4%) “male”, and seven (1.5%) de-

scribed themselves as “diverse”. When taking a look

Introducing Digital Education as a Mandatory Subject: The Struggle of the Implementation of a New Curriculum in Austria

217

at the age groups, 95 (20.9%) teachers were “under

30 years old”, 141 (31.1%) “30 to 39 years old”, 105

(23.1%) “40 to 49 years old”, 90 (19.8%) “50 to 59

years old”, and 23 (5.1%) “60 years or older”. Con-

cerning years in service the participants stated that

127 (28%) have been working at school “five or less

years”, 108 (23.8%) “five to ten years”, 82 (18.1%)

“eleven to 20 years”, 70 (15.4%) “21 to 30 years”,

and 67 (14.8%) “30 or more years”.

3.2.2 Teacher Training Course Results

This section wanted to know more about the teacher

training courses. One-hundred-thirty-two (29.1%)

teachers affirmed that they currently visit a teacher

training course in digital education, whereas 322

(70.9%) don’t. Concerning the question, if they plan

to attend in the future, 31 (9.6%) chose “yes”, 131

(40.7%) “maybe”, and 160 (49.7%) “no”.

3.2.3 Personal Experience Results

When looking at the results of the section concerning

personal experiences, the following emerged:

The question “I think the content of the curricu-

lum for the subject “Digital Education” makes sense”

was answered by 42 (9.3%) with “strongly agree”,

by 211 (46.5%) with “agree”, by 122 (26.9%) with

“neither agree nor disagree”, by 67 (14.8%) with

“disagree”, and by twelve (2.6%) with “strongly dis-

agree”. The median lies with “agree”, whereas the

arithmetic mean can be found at 2.55 (when number-

ing the Likert scale from one to five downwards).

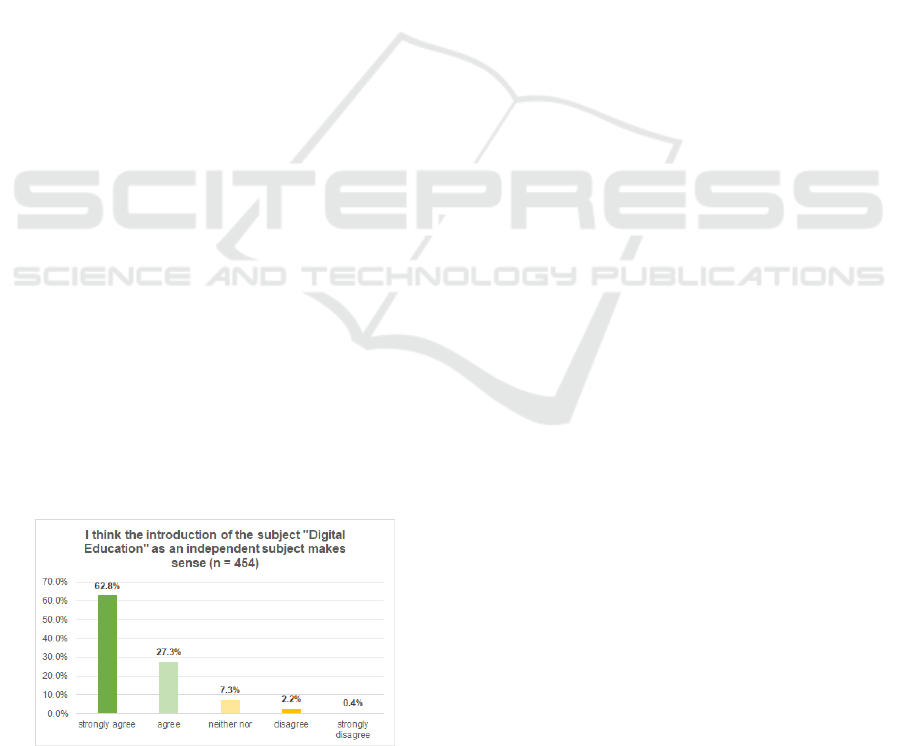

“I think the introduction of the subject “Digital

Education” as an independent subject makes sense”

was rated by the teachers like the following (see

Figure 3): two-hundred-eighty-five (62.8%) partic-

ipants “strongly agree”, 124 (27.3%) “agree”, 33

(7.3%) “neither agree nor disagree”, ten (2.2%) “dis-

agree”, and two (0.4%) “strongly disagree (median =

“strongly agree”, arithmetic mean = 1.50).

Figure 3: I think the introduction of the subject “Digital Ed-

ucation” as an independent subject makes sense (n = 454).

Ten (2.2%) of the attendants “strongly agreed” to

the statement “I think it was better when “Digital Ed-

ucation” could still be integrated into other subjects”,

33 (7.3%) “agreed”, 103 (22.7%) “neither agreed

nor disagreed”, 171 (37.7%) “disagreed”, and 137

(30.2%) “strongly disagreed (median = “disagree”,

arithmetic mean = 3.86).

Questions (2) “I think the introduction of the sub-

ject “Digital Education” as an independent subject

makes sense” and (3) “I think it was better when “Dig-

ital Education” could still be integrated into other sub-

jects” together answered the first research question

that was stated like the following (RQ1) Which type

of implementation of the curriculum “Digital Educa-

tion” preferred teachers: integrated or stand-alone? In

total 90.1% “strongly agreed” or “agreed” that they

prefer the stand-alone version of the curriculum. As

a control sequence the question “I think it was better

when “Digital Education”could still be integrated into

other subjects” verified this hypothesis, when 67.9%

“disagreed” or “strongly disagreed”.

The next part consisted of a self-assessment of

teachers in the various topics of the curriculum. One-

hundred-twenty-two (26.9%) rated their knowledge in

the field of “analyzing and reflecting on social aspects

of media change and digitization” with “very good”,

218 (48%) “good”, 89 (19.6%) “intermediate”, 21

(4.6%) “poor”, and four (0.9%) “very poor”. When

numbering the Likert scale from one to five down-

wards, the median is “good”, whereas the arithmetic

mean is 2.05.

Concerning the topic “handle data, information,

and information systems responsibly”, 197 (43.3%)

classified themselves as “very good”, 195 (43%)

“good”, 49 (10.8%) “intermediate”, eleven (2.4%)

“poor”, and two (0.4%) “very poor” (median =

“good”, arithmetic mean = 1.74).

The section “communicating and cooperating us-

ing IT systems” was rated by 177 (39%) teachers with

“very good”, 197 (43.4%) “good”, 64 (14.1%) “in-

termediate”, 14 (3.3%) “poor”, and one (0.2%) “very

poor” (median = “good”, arithmetic mean = 1.82).

On the contrary, as shown in Figure 4, 99 (21.8%)

participants claimed their knowledge on “creating and

publishing content digitally, designing algorithms,

and programming” is “very good”, 102 (22.5%)

“good”, 119 (26.2%) “intermediate”, 82 (18.1%)

“poor”, and 52 (11.5%) “very poor” (median = “in-

termediate”, arithmetic mean = 2.75). This answers

the second research question, that was stated like the

following: (RQ2) Are there any topics of the curricu-

lum teachers struggle with? If so, which?

Regarding the topic “assess offers and options for

a world shaped by digitization and use them respon-

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

218

Figure 4: Creating and publishing content digitally, design-

ing algorithms, and programming (n = 454).

sibly”, 143 (31.5%) teachers rated themselves “very

good”, 208 (45.8%) “good”, 81 (17.8%) “intermedi-

ate”, 20 (4.4%) “poor”, and two (0.4%) “very poor”

(median = “good”, arithmetic mean = 1.96).

The last questions from this survey contained

teacher support. Three-hundred-and-fifteen (69.4%)

teachers stated that they “would like to have more

support in implementing the “Digital Education” cur-

riculum”, whereas 113 (24.9%) claimed that they do

not need any support. Twenty-six (5.7%) declared

“other”.

3.3 Discussion

The gender distribution, with 68.1% female, 30.4%,

and 1.5% diverse, is representative for Austria. Fur-

thermore, it is not surprising, that the upper two age

groups (50 or older) do not want to teach a brand

new subject and is therefore under-represented with

24.9%.

In Austria every teacher usually studies two sub-

jects and therefore covers at least two at a time at

school. Because of a lack of teachers, administration

also deploys their staff in other, field related, subjects.

This is most often seen in Middle School. As nearly

half of the participants state that they are employed at

a Middle School, it is not uncommon that in this sur-

vey each teacher covers 3.6 subject on average. The

two most stated second subjects covered by the teach-

ers who implement “Digital Education” are Mathe-

matics (185) and Computer Science (153). No won-

der that teachers who already have STEM subjects,

tend to teach the new curriculum as well. Remark-

ably, the next subject in line is German (100) closely

followed by Physical Education (99), which both have

no connection at all to the curriculum of “Digital Ed-

ucation”.

Only 132 (29.1%) claimed that they currently visit

a teacher training course. This could be due to the

lack of vacant spots, as there was a run of appli-

cants for a place at those classes. The organizing

teacher training colleges even limited the spots to

active teachers with recommendations of respective

headmasters, only. Even though there was a keen

demand. Half of those who do not attend a course

at the moment, do not want to in the future. This

could be due to the fact that lots of the participants

of this survey teach Computer Science, which is very

similar to the new curriculum. Also, in the second

most subject Mathematics, educators already tend to

use digital devices for many years. Some state that

they find themselves “too old“ or “in the last years“

of their job, but still this does not seem to justify no

further professional education at all. Of course the

geographical location of the teacher training colleges

plays an important role, as most of the time they can

be found in central regions. To guarantee accessibility

for all teachers, colleges already think about a course

that is fully online. Still, such a teacher training is

time-consuming and a lot of extra work, most often

at weekends. Considering that, teachers also brought

forth that they cannot attend because they have “little

children to care for”.

Interestingly, only 22.9% of the participants

claimed that they have troubles when preparing for

“Digital Education” class and 23.5% stated that they

do not have sufficient teaching material. Compared

to one of the last questions, 69.4% “would like to

have more support in implementing the “Digital Ed-

ucation” curriculum” (see Figure 7), this seems odd.

In conclusion, it can be said that there is already lots

of available teaching material but still teachers need

help in dealing with the unfamiliar curriculum.

When looking at the topics of the curriculum,

there is only one that stands out. Fifty-five percent of

the participants rated their knowledge in the field of

“creating and publishing content digitally, designing

algorithms, and programming” with “intermediate“ to

“very poor”, which is alarming, considering the fact

that those teachers already implement the curriculum

(see Figure 5).

4 CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

This paper evaluated a study carried out from Septem-

ber to December 2022 with a focus on the adoption

of the compulsory curriculum “Digital Education” in

Austria in 2022. In conclusion, both research ques-

tions could be answered:

1. Which type of implementation of the curriculum

“Digital Education” preferred teachers: integrated

or stand-alone? Overall, 90.1% of respondents in-

dicated that they “strongly agreed” or “agreed”

that they prefer the curriculum as a stand-alone.

Introducing Digital Education as a Mandatory Subject: The Struggle of the Implementation of a New Curriculum in Austria

219

Figure 5: Rating of knowledge of the topics of the curricu-

lum (n = 454).

This hypothesis was supported by the control

question, “I think it was better when “Digital Ed-

ucation” could still be integrated into other sub-

jects”, with 67.9% “disagreeing” or “strongly dis-

agreeing”.

2. Are there any topics of the curriculum teachers

struggle with? If so, which? The participants’

understanding of “creating and publishing con-

tent digitally, designing algorithms, and program-

ming” was assessed by 55% of them as “interme-

diate” to “very poor”.

With the introduction of the compulsory sub-

ject another problem appeared, as currently no en-

tire “Digital Education” studies in Austrian teacher

education exist, as there is for other traditional sub-

jects. In autumn 2022 postgraduate training for teach-

ers started to tackle the lack of fully trained staff in

“Digital Education”. Still, there seems to be an ur-

gent need for establishing and expanding the subject-

specific expertise of teachers especially in the field of

“creating and publishing content digitally, designing

algorithms, and programming”.

REFERENCES

BGBLA (2018). Bundesgesetzblatt der Republik

¨

Osterreich: 71. Verordnung.

BMBWF (2022). Projekt Lehrpl

¨

ane NEU - Fachlehrplan

Digitale Grundbildung.

Brinda, T., Br

¨

uggen, N., Diethelm, I., Knaus, T., Kommer,

S., Kopf, C., Missomelius, P., Leschke, R., Tilemann,

F., and Weich, A. (2019). Frankfurt-Dreieck zur Bil-

dung in der digital vernetzten Welt – Ein interdiszi-

plin

¨

ares Modell.

Buckingham, D. (2020). Epilogue: Rethinking digital liter-

acy: Media education in the age of digital capitalism

— Buckingham — Digital Education Review.

Bundesministerium, BMBWF (2018). Verbindliche

¨

Ubung

Digitale Grundbildung – Umsetzung am Schulstan-

dort.

Bundesministerium f

¨

ur Bildung, Wissenschaft und

Forschung (2018). Masterplan f

¨

ur die Digitalisierung

im Bildungswesen.

Connections Academy (2013). How online education builds

career readiness with the 4 cs.

Ferrari, A. (2013). Digital Competence in Practice: An

Analysis of Frameworks. Joint Research Centre of the

European Commission., page 91.

Grandl, M. and Ebner, M. (2017). Informatische Grundbil-

dung - ein L

¨

andervergleich. Medienimpulse, 55.

Informatikportal AHS

¨

Osterreich (2022). Kompetenzraster

Digitale Grundbildung.

Joshi, A., Kale, S., Chandel, S., and Pal, D. K. (2015). Lik-

ert scale: Explored and explained. British Journal of

Applied Science & Technology, 7(4):396.

Kask, M. and Feller, N. (2021). Digital education in europe

and the eu’s role in upgrading it.

Langmeyer, A., Guglh

¨

or-Rudan, A., Naab, T., Urlen, M.,

and Winklhofer, U. (2020). Kindsein in Zeiten von

Corona: Ergebnisbericht zur Situation von Kindern

w

¨

ahrend des Lockdowns im Fr

¨

uhjahr 2020.

PH Ober

¨

osterreich (2022). Digitale Grundbildung in der

Sekundarstufe.

Polaschek, M. (2022). Erledigung BMBWF -

¨

Osterreichisches Parlament - 9338.

Redecker, C. and Punie, Y. (2017). European framework for

the digital competence of educators: DigCompEdu.

Publications Office of the European Union.

Sturm, W. (2020). Digitale Bildung im 21. Jahrhundert

– Versuch, Wirklichkeit, Vision. Schwerpunkt BIL-

DUNGSverSUCHE, 15.

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

220