Complex Thinking in Interdisciplinarity: An Exploratory Study in

Latin American Population

Jorge Sanabria-Z

1a

, María Soledad Ramírez-Montoya

1b

, Francisco José García-Peñalvo

2c

and Marco Cruz-Sandoval

1d

1

Institute for the Future of Education, Tecnologico de Monterrey, Monterrey, Mexico

2

Salamanca University, Mexico

Keywords: Professional Education, Educational Innovation, Future of Education, Complex Thinking, Higher Education,

Latin American Countries, LATAM.

Abstract: In the context of Latin America, there are few studies that analyze complex thinking linked to disciplinary

analysis. In this sense, locating the characteristics promoted by the different disciplines presents an

opportunity to scale higher order competencies such as those of complex thinking. This article aims to show

the results of a study that seeks to show the perception of complex thinking competence in young university

students in the Latin American context. A multivariate descriptive statistical analysis has been carried out.

Among the main findings we identified that there is a higher degree of perception of male students in Latin

America on complex thinking competence and that this pattern is found in most of the countries in the sample.

1 INTRODUCTION

Assessment of low- and high-order thinking skills is

frequently performed following the Cognitive

Process dimension of Bloom's taxonomy of

educational objectives, namely the progressive low-

to-high ladder of remember, understand, apply,

analyze, evaluate, and create. The taxonomy has

undergone a revision that separates it into Knowledge

dimension and Cognitive Process dimension

(Anderson, 2005). This breadth has made it possible

to accommodate in the Knowledge dimension

characteristics of the experimental context (e.g., type

of academic subject) on a concrete-to-abstract

continuum of factual, conceptual, procedural and

metacognitive knowledge (Poluakan et al., 2019).

Therefore, in the case of assessment of thinking skills

within a disciplinary area, it has opened the

possibility to factor the characteristics of the area into

the Knowledge dimension for their consideration, for

instance, by labeling it as more or less technology

oriented.

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8488-5499

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1274-706X

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9987-5584

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5703-4023

In the Latin American university context,

disciplinary areas can be classified as either

technology or non-technology based. In this area, the

development of high-level competencies, such as

reasoning for complexity (Lipman, 1997, Morin,

1990), can support training in higher education from

multiple perspectives, considering the

characterisation of students with their socio-

demographic and disciplinary characteristics. The

aim of this article is to analyse the perception of

students from different disciplines, in terms of their

level of mastery of the competency of reasoning for

complexity, to locate possibilities to further enhance

high capacities in future professionals.

1.1

Higher Order Thinking Skills in

Education

High-order thinking skills assessment have been an

area of interest throughout the evolution of

philosophy and psychology. Historically, the path to

defining thinking skills was already observing a

288

Sanabria-Z., J., Ramírez-Montoya, M., García-Peñalvo, F. and Cruz-Sandoval, M.

Complex Thinking in Interdisciplinarity: An Exploratory Study in Latin American Population.

DOI: 10.5220/0011856000003470

In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2023) - Volume 2, pages 288-295

ISBN: 978-989-758-641-5; ISSN: 2184-5026

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

certain maturity in the middle of the twentieth

century, where Newman (1990) indicated the

importance of including deep knowledge resources

and thoughtfulness dispositions to solve problems,

which must be evaluated in order to be able to

develop them. Broadly defined, higher-order thinking

skills refer to an advanced cognitive process that

involves the manipulation of previous thinking

schemes and new information to solve problems and

challenges (Heong et al., 2011). The revised Bloom's

taxonomy has been a widely accepted approach to

identifying higher-order thinking skills in higher

education, particularly aimeda at observing critical

thinking and problem solving (Hadzhikoleva et al.,

2019). The rebirth of Bloom’s taxonomy has also

promote the creation of new instruments to measure

thinking skills, and it continues to be a point of

comparison and inspiration for other alternatives.

Although there are numerous examples at different

educational levels, the implementation of educational

strategies that integrate the development of thinking

at the higher educational level continues to maintain

great interest.

Within the context of higher education, the

consideration of higher order thinking skills in

curricular activities has taken a vital role in the

teaching-learning process. Appropriate incorporation

of the concept of thinking skills from a systemic

perspective should take into account the perceptions

of both students and teachers (Shukla &

Dungsungnoen, 2016), nevertheless, students are the

natural focus for the development of thinking skills.

To this end, a study conducted by Yuliati and Lestari

(2018) on higher education students, have found that

students poorly comprehend questions aimed at

identifying higher-order thinking skills, which

beyond comprehension, may also be an indicator of

the need for better instruments to measure perception

of thinking. Certainly, exploration for the

development of thinking skills in educational

contexts, in addition to instructional design, involves

factors such as the type of environment and the type

of tools used for learning.

Currently, in both formal and informal

educational settings, the use of technologies for

learning has become the mainstream. The framework

of the fourth industrial revolution has brought with it

Education 4.0, which embraces the use of

technologies for the development of 21st century

skills (Qureshi et al., 2021). Chinedu et al. (2015)

discussed teaching practices for developing higher-

order thinking skills in design and technology formal

education contexts, featuring strategies that entail the

importance of systematic planning and collaborative

activities for creativity that enable students to develop

insights and hence work out solutions. With respect

to field implementations for non-formal education,

Sanabria-Z et al. (2022) have found a window of

opportunity to create native technologies that allow

for greater citizen involvement leading to their

development of complex thinking. With this

assimilation of technologies in education for the

development of competencies, it becomes significant

to highlight the current perception in the development

of thinking competencies.

1.2 Complex Thinking from

Disciplinary Analysis

The development of complex thinking promotes

analysis in an integrated rather than fragmented way,

as an interrelated system and not as disconnected

parts. Morin (2022) calls for "complex thinking",

especially with the experience of the

multidimensional planetary crisis resulting from the

COVID pandemic. Teixeira et al. (2021) associate

complexity in the combination of computational and

qualitative methods to extract definitions and analyse

their use. Decision-making through complex thinking

is also associated in its conceptualisation

(Mohammadi-Shahboulaghi et al., 2021). As a high-

level competence, reasoning for complexity involves

scientific, systemic, critical and innovative thinking

(Ramírez-Montoya et a., 2022). Developing

complexity reasoning competences involves the

interrelationship of analysing the parts in the whole

and the whole in its interconnected parts.

Complex thinking has a substantial challenge in

training across disciplines because of the crossover

that is required towards interdisciplinarity.

Domínguez (2022) puts forward ideas on

interdisciplinarity and its presence at the educational

level in links with the humanities, as an engine that

increases its quality in combination with other

disciplines. In the same sense, Baena-Rojas et al.

(2022) through a bibliometric analysis of the concept

of complexity locate incidence in various fields and

the breadth towards multidisciplinarity. And in a

practical analysis with students from various

disciplines, Vázquez-Parra et al. (2021) found a

greater preponderance of systemic thinking with

students from the disciplines of Engineering,

Business and Humanities, while the highest means for

critical thinking were found in architecture students.

Interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary has a field of

action in the development of complex thinking.

Particularly in the context of Latin America, there

are few studies that analyse complex thinking linked

Complex Thinking in Interdisciplinarity: An Exploratory Study in Latin American Population

289

to disciplinary analyses. Among them, Maturo (2009)

finds that, in Latin America, the philosophical

discussion that stimulates complex thinking

necessarily requires culturally diverse poetic

experiences that are part of the meanings of historical

reality. In the area of health, De Bortoli et al. (2017)

emphasise that nursing education in Latin America

and the Caribbean promotes nursing curricula that

include the principles and values of Universal Health

and promote the development of critical and complex

thinking. For its part, a Mexican study found the

relationship between complex thinking and social

entrepreneurship in higher education students (Cruz-

Sandoval, et al., 2022), as well as research in the area

of education that proposes an international learning

experience between Mexican and Spanish students

(Romero-Rodríguez et al., 2022). In this sense,

locating the characteristics promoted by the different

disciplines presents an opportunity to scale higher-

order competences such as those of complex thinking.

2 METHODOLOGY

To carry out the present study, a population sample of

150 undergraduate students from different Latin

American countries was taken for convenience (see

Table 1). The sample consists of 75 men and 75

women from different disciplinary areas. The study

was carried out during the period August - December

2022. A questionnaire was administered via Google

Forms in which the students responded voluntarily.

Taking into account that the study involves human

subjects, and being a pilot test, the implementation

has been regulated and approved by the

interdisciplinary research group R4C with the

technical support of Writing Lab. Both entities belong

to the Institute for the Future of Education (IFE) of

the Tecnológico de Monterrey.

Regarding the instrument to evaluate the level of

perception in the development of the complex

thinking competency, the validated eComplexity

instrument has been carried out. The purpose of this

instrument is to measure the participants’ perception

of the development of the complex thinking

competency and its sub-competencies. The instrument

comprises 25 items (i.e., questions) linked to each of

the sub-competencies of complex thinking: scientific

thinking; critical thinking; innovative thinking; and

systemic thinking. In this sense, the participant

responds to each of the items according to their

perception of achievement on a 5-level Likert scale.

The items of this instrument can be reviewed in Cruz-

Sandoval, Vázquez-Parra, and Carlos-Arroyo (2023).

Table 1: Participant data and gender. Source: Created by the

authors.

Country Men Women Total

Ar

g

entina 2 2 4

Chile 18 30 48

Colombia 3 3 6

Dominican

Re

p

ublic

3 3 6

Ecuado

r

35 23 58

Guatemala 2 2 4

Mexico 12 12 24

Total 75 75 100

Subsequently, a descriptive statistical analysis of

the data was carried out using the computation

software R (R Core Team, 2017) and RStudio (

RStudio Team , 2022). The analysis consisted mainly

of measures of central tendency (i.e., arithmetic

mean, standard deviation), complemented with

boxplot analysis and violin plot analysis. An ANOVA

analysis was also performed to observe the

significance of the difference in mean values by

gender in Latin American university students. It is

worth mentioning that, as far as possible, a

comparison was made between countries and a

comparison by gender according to the country to

which the students belong.

3 RESULTS

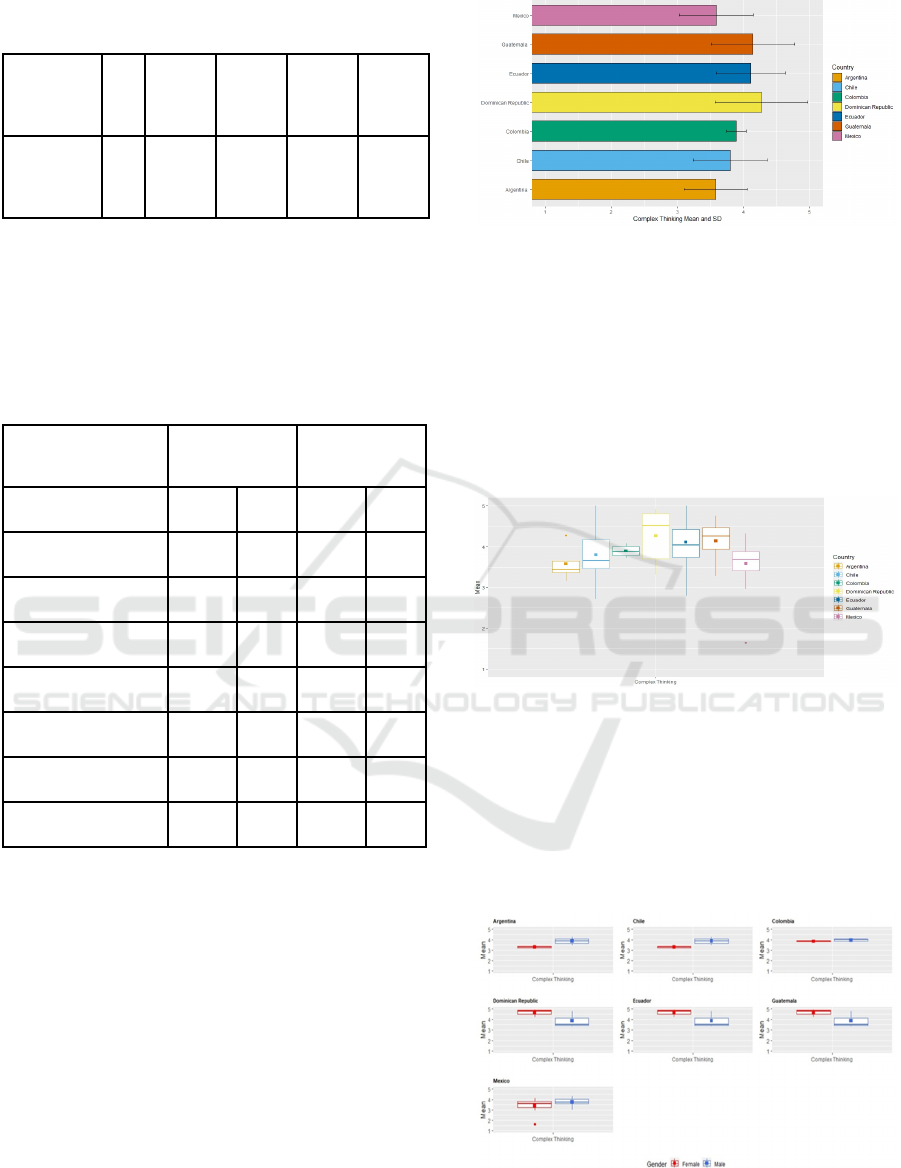

Figure 1 shows the first approach to the results

obtained. It shows the percentage of students per

country in Latin American context with respect to the

mean values obtained in perception of the complex

thinking competency. The results are shown in a 10

X 10 grid in which each square represents 10%.

Likewise, each square is color-coded according to the

range in mean values obtained in the perception of the

development of the competency.. In this sense, the

figure illustrates that Chile (10%) and Ecuador (2%)

present the highest percentage of population with

perception levels between 2 and 3. It is important to

mention that the results are relative to each country

and not to the population in general.

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

290

Figure 1: Mean values in the perception of the development

of complex thinking in [%] by country. Source: Created by

the authors.

Given that the above results could yield spurious

analyses, a more in-depth analysis has been made. In

this sense, Table 2 shows the mean values and

standard deviation (s) with respect to the perception

of the development of complex thinking competency

in Latin American students by gender. From the table

it can be observed that men are perceived as having a

higher development than their female peers,

presenting higher mean values. Likewise, the

standard deviation value indicates how dispersed the

behavior is with respect to the mean value. In this

sense, the deviation in men (0.50), being lower than

in women (0.61), would indicate that there is less

dispersion around the value of perception in men.

Table 2: Complex Thinking. Mean values and standard

deviation in perception of the development of complex

thinking by gender. Source: Created by the authors.

Gende

r

Mean S

d

Male 4.02 0.50

Female 3.80 0.61

In this context, Figure 2 illustrates the previous

results in a better way. It shows Latin American male

students with a higher perception in the development

of complex thinking and with a smaller dispersion

with respect to the mean value compared to their

female peers.

Figure 2: Complex thinking. Overall results. Mean values

and standard deviation in perception of the development of

complex thinking by gender. Source: Created by the

authors.

On the other hand, Figure 3 shows the empirical

Kernel-type distribution density analysis in a

smoothed diagram. From the figure it can be observed

that in men the distribution density is higher at mean

values of perception between 4 and 4.5, while in

women the distribution density is higher at values of

3 and 3.5.

Source: Created by the authors.

Figure 3: Flat violinplot. Distribution density. Kernel

density. Smoothed histogram of perception in the

development of complex thinking by gender.

On the other hand, in order to understand if there

is a significant difference in the perception of the

development of complex thinking between men and

women, an ANOVA analysis was performed. The

results of the analysis ( see Table 3) , show that there

are significant differences (p<=0.05) between male

and female students in how they perceive themselves

with respect to this competency in the Latin American

context.

On the other hand, the analysis by country is

shown in Table 4. It shows that the countries with

high average values in the perception of the

development of complex thinking are the Dominican

Republic, Guatemala and Ecuador. On the other hand,

development of this competency are Argentina,

Mexico, Chile and Colombia. Similarly, the table

shows the analysis of the average values of perception

Complex Thinking in Interdisciplinarity: An Exploratory Study in Latin American Population

291

Table 3: Complex thinking. ANOVA analysis. Men vs

Women. Source: Created by the authors.

Complex

Thinking

Df Sum

Sq

Mean

Sq

F

value

Pr(>F)

Men vs

Women

1 1.782 1.782 5.66 0.018

by gender according to the country to which they

belong. The table shows that, with the exception of

the Dominican Republic and Guatemala, men are

perceived as having a greater development of

complex thinking.

Table 4: Complex thinking by country and gender. Source:

Created by the authors.

Men Women

Countr

y

Mean S

d

MeanS

d

Ar

g

entina 3.86 0.59 3.30 0.20

Chile 4.02 0.59 3.67 0.51

Colombia 3.95 0.20 3.84 0.08

Dominican Rep. 3.88 0.80 4.65 0.36

Ecuado

r

4.16 0.47 4.04 0.59

Guatemala 3.72 0.62 4.56 0.28

Mexico 3.76 0.37 3.41 0.67

As a complement to the previous results, Figure 4

illustrates the behavior in perception of mean values

and deviation(s) of students with respect to complex

thinking by country. The figure shows a similar

behavior between Guatemala and Ecuador. Likewise,

Colombia and Chile show a similar trend. On the

other hand, Mexico and Argentina show the lowest

mean values. It should also be noted that although the

Dominican Republic is the country with the highest

mean value in perception, it is the one that shows the

greatest standard deviation with respect to the mean

value.

In this context, in order to learn more about

the students' perception of complex thinking

competency, a boxplot analysis by country has been

performed. The interesting thing about this analysis

is that it helps to understand the dispersion of our

Figure 4: Complex thinking. Mean and standard deviation

by country with respect to the perception in the

development of complex thinking. Source: Created by the

authors.

data and the outliers (see Figure 5). In this sense, it is

possible to observe that the Dominican Republic,

Chile and Ecuador show a more dispersed behavior,

while Argentina and Colombia show less dispersion

in the students' perception of the development of

complex thinking.

Figure 5: Boxplot analysis of the perception in the

development of complex thinking by country. Source.

Created by the authors.

On the other hand, Figure 6 illustrates the Boxplot

analysis by gender of each country with respect to

their perception of the development of complex

thinking. The figure shows that the general behavior

(with the exception of the Dominican Republic,

Figure 6: Boxplot analysis of the perception in the

development of complex thinking by country and by

gender. Source: Created by the authors.

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

292

Guatemala and Ecuador) is that men perceive

themselves better in the development of complex

thinking competencies. Likewise, it is important to

highlight that women show less dispersion in

perception than men, that is, although the mean

values in women in some countries are low, the

dispersion is lower than in their male peers (despite

the fact that men present higher mean values).

Finally, Figure 7 shows the analysis of complex

thinking by type of discipline, showing how students

from the social sciences are perceived as having the

greatest development of complex thinking. On the

other hand, students belonging to engineering and

technology disciplines are those who are perceived as

having the least development in complex thinking.

On the other hand, students of humanities, medical

sciences and natural sciences show a similar behavior

in the average value of perception.

Figure 7: Complex thinking. Boxplot analysis by discipline.

Source: Created by the authors.

4 DISCUSSION

Students in Latin America in technological

disciplinary areas are perceived with a lower degree

of development of high-order thinking skills. The

analysis of complex thinking in students by discipline

shows how those in social sciences are perceived with

greater development, while those in areas related to

technology are perceived with less development of

complex thinking. This deficiency could be related to

the lack of technological developments that are linked

to the development of student involvement, as

pointed out by Sanabria-Z et al. (2022). This scenario

suggests that the stereotype of the study of

technological areas where it focuses heavily on

practice leaving aside the context may still be

governing despite the educational evolution.

Latin American male students tend to have self

greater perception in the development of complex

thinking. Based on what is represented in the BoxPlot

analysis, the perception in the development of

complex thinking by country and gender differs in

favor of males, with less dispersion of the data. This

finding, seen from the perspective of instructional

design, is supported by what Maturo (2009) points out

about Latin America, calling for the importance of

considering the cultural aspects of historical reality

when constructing narratives for the development of

thought. As a whole, the contextual nature of

educational environments where high-order thinking

skills are sought to be developed, plays a fundamental

role that is highly considered by those who design

learning activities and seek to measure the

development of competencies.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The impact of the identification of thinking skills is

of great value in the context of education 4.0, which

strongly links skills with the use of technologies. In

this study, we sought to present the state of the

perception of students from different disciplines

about the reasoning competence due to complexity,

considering the difference between disciplinary areas

with and without a technological base. Among the

main findings we identified that there is a higher

degree of perception of male students in Latin

America about complex thinking competence and

that this pattern occurs in most of the sample

countries.

The implications of this study for best practices

show that it is necessary to continue strengthening the

way of constructing reasoning development activities

for complexity considering the inclusion in the

instructional design of activities. Likewise, the

analyses give rise to reflection on how the research

has a wide area of application that ranges from

knowing the perception of students and instructors,

teaching conditions, and instruments for measuring

competencies.

Some limitations of the study are limited to the

type of sample that is limited to a group of countries

but not to the entirety of Latin America; the broad

definition of the disciplinary areas between

technological and non-technological without

specifying the particularities of the subject of study;

and the lack of observation of perception over time to

identify the passage of low-order thinking skills

towards high-order skills in students. Some

limitations of the study are limited to the type of

sample that is limited to a group of countries but not

to the entirety of Latin America; the broad definition

of the disciplinary areas between technological

and non-technological without specifying the

Complex Thinking in Interdisciplinarity: An Exploratory Study in Latin American Population

293

particularities of the subject of study; and the lack of

observation of perception over time to identify the

passage of low-order thinking skills towards high-

order skills in students.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge the financial and technical

support of Writing Lab, Institute for the Future of

Education, Tecnologico de Monterrey, Mexico, in

producing this work and the financial support from

Tecnologico de Monterrey through the “Challenge-

Based Research Funding Program 2022”. Project

name” OEM4C: Open Educational Model for

Complex Thinking” with Fund ID # I001 - IFE001 -

C1-T1 – E ”

REFERENCES

Anderson, L. W. (2005). Objectives, evaluation, and the

improvement of education. Studies in Educational

Evaluation, 31(2-3), 102-113. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.stueduc.2005.05.004

Baena-Rojas, J. J., Ramírez-Montoya,M.S., Mazo-Cuervo,

D.M. & López-Caudana, E. O. (2022). Traits of

Complex Thinking: A Bibliometric Review of a

Disruptive Construct in Education. Journal of

Intelligence 10(37). https://doi.org/10.3390/jintellig

ence10030037

Chinedu, C. C., Olabiyi, O. S., & Kamin, Y. B. (2015).

Strategies for Improving Higher Order Thinking Skills

in Teaching and Learning of Design and Technology

Education. Journal of Technical Education and

Training, 7(2), 135-143. https://publisher.uthm.

edu.my/ojs/index.php/JTET/article/view/1081

Cruz-Sandoval, M., Vázquez-Parra, J.C. & Alonso-Galicia,

P. (2022). Student Perception of Competencies and

Skills for Social Entrepreneurship in Complex

Environments: An Approach with Mexican University

Students. Social Sciences, 11(7), Art.314.

https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11070314

Cruz-Sandoval, M., Vázquez-Parra, J.C., and Carlos-

Arroyo, M. (2023) Complex thinking and social

entrepreneurship. An approach from the methodology

of compositional data analysis, HELIYON.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13415

De Bortoli Cassiani, S. H., Wilson, L. L., De Souza Elias

Mikael, S., Peña, L. M., Grajales, R. A. Z., McCreary,

L. L., . . . Gutierrez, N. R. (2017). The situation of

nursing education in latin america and the caribbean

towards universal health. Revista Latino-Americana De

Enfermagem, 25 doi:10.1590/1518-8345.2232.2913

Domínguez, F. V. (2022). Interdisciplinarity in higher

education: a look from the opposition to mercantilism.

[la interdisciplinariedad en la educación superior: una

mirada desde la oposición al mercantilismo]

Universidad y Sociedad, 14(5), 369-383.

Hadzhikoleva, S., Hadzhikolev, E., & Kasakliev, N. (2019).

Using peer assessment to enhance higher order thinking

skills. Tem Journal, 8(1), 242-247.

Heong, Y. M., Othman, W. B., Yunos, J. B. M., Kiong, T.

T., Hassan, R. B., & Mohamad, M. M. B. (2011). The

level of marzano higher order thinking skills among

technical education students. International Journal of

Social Science and Humanity, 1(2), 121.

Lipman, M. (1997). Pensamiento complejo y educación.

Ediciones de la Torre.

Maturo, G. (2009). Poetic reason and complex thought. [La

razón poética y el pensamiento complejo] Utopia y

Praxis Latinoamericana, 14(47), 127-132.

Morin, E. (1990). Introducción al pensamiento complejo.

Gedisa.

Morin, E. (2022). Lecciones de un siglo de vida. Paidos

Estado y Sociedad.

Newmann, Fred M. "Higher order thinking in teaching

social studies: A rationale for the assessment of

classroom thoughtfulness." Journal of curriculum

studies 22.1 (1990): 41-56. doi:10.1080/0022027900

220103

Poluakan, C., Tilaar, A. L., Tuerah, P., & Mondolang, A.

(2019). Implementation of the revised bloom taxonomy

in assessment of physics learning. Proceedings of the

1st International Conference on Education, Science,

and Technology (ICESTech).

Qureshi, M. I., Khan, N., Raza, H., Imran, A., & ismail, F.

(2021). Digital Technologies in Education 4.0. Does it

Enhance the Effectiveness of Learning? A Systematic

Literature Review. International Journal of Interactive

Mobile Technologies (iJIM), 15(04), 31–47.

https://doi.org/10.3991/ijim.v15i04.20291

R Core Team. (2017). A Language and Environment for

Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical

Computing. https://www.r-project.org/

Mohammadi-Shahboulaghi, F., Khankeh, H., &

HosseinZadeh, T. (2021). Clinical reasoning in nursing

students: A concept analysis. Nursing Forum, 56(4),

1008-1014. doi:10.1111/nuf.12628

Ramírez-Montoya, M. S., Castillo-Martínez, I.M., Sanabria-

Zepeda, J.C., & Miranda, J. (2022). Complex Thinking

in the Framework of Education 4.0 and Open

Innovation—A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of

Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity

8(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc8010004

Romero-Rodríguez, J. M., Ramirez-Montoya, M.S.,

Glasserman-Morales, L.D. & Ramos Navas-Parejo, M.

(2022). Collaborative online international learning

between Spain and Mexico: a microlearning experience

to enhance creativity in complexity. Education +

Training, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print.

https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-07-2022-0259

RStudio Team. (2022). RStudio: Integrated Development

for R (2022.2.2.485). RStudio, PBC. http://

www.rstudio.com/

Sanabria-Z, J., Alfaro-Ponce, B., González Peña, O. I.,

Terashima-Marín, H., & Ortiz-Bayliss, J. C. (2022).

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

294

Engagement and Social Impact in Tech-Based Citizen

Science Initiatives for Achieving the SDGs: A

Systematic Literature Review with a Perspective on

Complex Thinking. Sustainability, 14(17), 1-22.

http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/su141710978

Shukla, D., & Dungsungnoen, A. P. (2016). Student's

Perceived Level and Teachers' Teaching Strategies of

Higher Order Thinking Skills: A Study on Higher

Educational Institutions in Thailand. Journal of

education and Practice, 7(12), 211-219.

https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1099486

Teixeira de Melo, A., Caves, L. S. D., Dewitt, A., Clutton,

E., Macpherson, R., & Garnett, P. (2020). Thinking (in)

complexity: (in) definitions and (mis)conceptions.

Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 37(1), 154-

169. doi:10.1002/sres.2612

Vázquez-Parra, J.C.; Castillo-Martínez, I.M.; Ramírez-

Montoya, M.S.; Millán, A. (2022). Development of the

perception of achievement of complex thinking: A

disciplinary approach in a Latin American student

population. Education Sciences 12, Art. 289.

https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12050289

Yuliati, S. R., & Lestari, I. (2018). Higher-order thinking

skills (hots) analysis of students in solving hots

question in higher education. Perspektif Ilmu

Pendidikan, 32(2), 181-188.

Complex Thinking in Interdisciplinarity: An Exploratory Study in Latin American Population

295