Transportation Infrastructure and Market and Supplier Access:

How Do They Shape Foreign Direct Investment?

Natalia Vechiu

a

Aix Marseille Univ., CRET-LOG, Aix-en-Provence, France

Keywords: Foreign Direct Investment, Liner Shipping Connectivity Index, Market Access, Transportation Infrastructure.

Abstract: Although the benefits of transportation infrastructure for economic and social development are generally

unquestionable, depending on the transportation mode and the economic development of countries, sometimes

transportation infrastructure does not have the expected positive impacts, or it may even hinder economic

development. In this paper, we focus on the impact of different types of transportation infrastructure on

foreign direct investments, in a close relation to the market/supplier access as an essential determinant for

FDIs and thus, a potential significant interaction term with transportation infrastructure. Based on the new

economic geography models, we attempt to distinguish between international and domestic transportation

infrastructure in destination countries and test their impact on bilateral FDI stocks, in a gravity type setting.

We take the liner shipping bilateral connectivity index as a proxy for international infrastructure and railroads

density as a proxy for the domestic one. Using a panel dataset from 2008 to 2012, we find evidence that

different transportation infrastructures have different impacts depending on the countries’ economic

development level: international infrastructure has a strong and significant positive impact on FDIs, whereas

the impact of railroads depends on destination countries’ economic development.

1 INTRODUCTION

In over 50 years of accelerating globalization, foreign

direct investments (FDIs) have increased

dramatically, because of decreasing trading and

transportation costs, financial liberalization,

increasing market potential in developed and

developing countries etc. Between 1980 and 2020,

global inward FDIs have been multiplied by 60

reaching almost 50% (48.8%) of world GDP in 2020.

In order to attract FDIs, governments around the

world try to adopt policies based on financial

incentives, but also long-term economic development

measures such as improving communication and

transportation infrastructure. More precisely, related

to the latter, improvements and innovations in the

transportation have been associated with basically

every wave of the Schumpeterian growth model:

waterpower in the first wave, rail in the second, the

internal combustion engine in the third, aviation in the

fourth, digital networks in the fifth wave. However,

researchers have questioned the type of infrastructure

that would be the most beneficial as well as its

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3806-7353

distributional effects. Fogel (1962, 1964) argues that

in the US, investment was misdirected towards

railroads because of government policies promoting

rail transportation and that the river networks were

much more important for economic development than

railroads. Rose, Savage, Jenkins and Fransman

(2017) summarizes several transport infrastructure

projects failing to generate the expected high

economic benefits. Among them, the Coega project

(an industrial development zone around the port of

Coega in South Africa) mainly designed to attract

FDIs has failed to deliver he expected results.

Thus, we choose to focus on the link between

transportation infrastructure and FDI, in order to

identify the type of infrastructure that would be the

most efficient in attracting FDIs, as a function of

countries’ level of development. Martin and Rogers

(1995) and Behrens, Gaigné, Ottaviano and Thisse,

2007 (2007) show that in relatively poor countries,

improving the international infrastructure may lead to

industrial companies leaving the country, whereas

improving domestic, local infrastructure may lead to

industrial companies relocating into the country. But

Vechiu, N.

Transportation Infrastructure and Market and Supplier Access: How Do They Shape Foreign Direct Investment?.

DOI: 10.5220/0011970700003494

In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business (FEMIB 2023), pages 89-97

ISBN: 978-989-758-646-0; ISSN: 2184-5891

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

89

these main results have never been tested empirically.

Without attempting a full structural estimation of

these models, we follow Martin and Rogers (1995)

and Behrens et al. (2007) and try to disentangle the

direct and indirect effects that different types of

transportation infrastructure may have on FDIs, as a

function of countries’ economic development. We

take maritime transportation infrastructure (LSCI, the

bilateral liner shipping connectivity index) as a proxy

for international infrastructure and rail transportation

as a proxy for domestic infrastructure. Maritime

transportation allows many connections between

points in two different countries, whereas rail

transportation allows relatively less. Accordingly,

Redding and Turner (2015) show that rail appears as

the preferred mode for domestic transportation in

terms of ton-kilometres.

Consequently, the main value added of our study

is to test for the impact of different types of

transportation infrastructure on FDIs, in a gravity

panel type setting, as well as for interaction effects

between transportation infrastructure and recipient

countries’ level of economic development. To our

knowledge, the bilateral LSCI has never been tested

before as a determinant of bilateral FDIs. We also

deal with the market and supplier access issue put

forward by NEG models. The market access, also

called market potential, is a major FDI determinant,

which has usually been proxied by GDP or measures

based on GDP and distance. We follow Redding and

Venables (2004) and consider a more comprehensive

measure of market as well as supplier access based on

countries’ capacity to export and import and their

proximity to world markets.

Finally, our paper is structured as follows: after a

review of the theoretical and empirical literature in

section 2, section 3 describes the empirical model

with its theoretical background as well as the data and

methodology; in section 4, we present and discuss the

results, while section 5 concludes.

2 LITERARURE REVIEW

Research on the macro- or microeconomic links

between transportation infrastructure and FDI is

scarce. However, given that it deals with trade costs

which commonly also include transportation costs,

some theoretical insights can be drawn from the NEG

and the international trade literature. Especially,

footloose capital models (Martin & Rogers, 1995;

Baldwin, Forslid, Martin, Ottaviano, & Robert-

Nicoud, 2003) allow us to draw some conclusions on

the link between trade/transportation costs and

international capital flows. One of the most important

conclusions of those models is that in the presence of

capital mobility, decreasing trade costs trigger the

agglomeration of economic activity in locations with

the biggest markets, with capital tending to relocate

to locations with the highest reward. Martin and

Rogers (1995) focus on the impact of different types

of transportation infrastructure on industry location.

They show that poor countries with good domestic

infrastructure attract foreign firms, whereas those

improving their international transportation

infrastructure encourage firms to leave the country.

On the other hand, the multinational firms literature

refines the analysis by taking into account the

different motives for companies to invest abroad.

More precisely, Markusen (1995) and Markusen and

Venables (1998) explain how relatively high trade

costs foster rather horizontal FDI, whereas Fujita and

Thisse (2006) explain how decreasing trade costs

foster vertical FDIs between developed and

developing countries. Empirical research on

transportation infrastructure and FDI is even scarcer

than the theoretical one. There is ample evidence on

the importance of transportation (especially

infrastructure) for economic development and

location of economic activity, but mostly at national

and regional level within countries, with no

consideration for FDIs.

Among the few notable contributions dealing with

transportation infrastructure and FDI, Hong (2007)

focuses on logistics firms, Castellani, Lavoratori and

Scalera (2021) focus on R&D and HQ activites,

Yeaple (2003) and Hanson, Mataloni, and Slaughter

(2005) deal with the importance of freight costs,

whereas Blyde and Molina (2015) analyse the impact

of a logistics index on FDIs and Shahbaz, Mateev,

Abosedra, Nasir and Jiao (2021) focus on FDI

determinants, including transportation infrastructure,

in France. Chen et al. (2023) show a positive impact

of infrastructure on FDI, but they deal mostly with

communications, not transportation infrastructure.

Saidi et al. (2020) show a positive impact of

transportation infrastructure on FDI attractiveness,

but they only focus on road transportation.

3 THE EMPIRICAL MODEL

3.1 Theoretical Background

Our empirical analysis is based on the NEG and

international trade literature. More precisely, we refer

to NEG models (Krugman, 1991; Baldwin et al.,

2003; Venables, 1996; Fujita & Thisse, 2006),

FEMIB 2023 - 5th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

90

assuming monopolistic competition in the production

of industrial goods and capital mobility, as well as on

those of the multinational activity literature

(Markusen, 1995; Markusen & Maskus, 2002;

Markusen & Venables, 1998; Fujita & Thisse, 2006).

Regarding FDI determinants and to the extent that

"regions" in NEG models may also represent

"countries" in the real world, we get three major

conclusions from these models:

when trade/transportation costs are

exogenous/endogenous, FDIs are attracted to

countries with high/low market potential or

market/supplier access

in poor countries, domestic transportation

infrastructure has a positive impact on FDIs

in poor countries, international transportation

infrastructure has a negative impact on FDIs.

Consequently, we have two main research

questions:

1. How is international transportation

infrastructure impacting FDI decisions as

opposed to domestic transportation

infrastructure?

2. To the extent that the market/supplier access can

be viewed as a proxy for countries' economic

development level, how do market/supplier

access and transportation infrastructure shape

FDI decisions, in rich as opposed to poor

countries?

In this regard, we define the following baseline

gravity equations:

OFDI

ijt

= MA

it

+ MA

jt

+ IntTRinfr

jt

+

DomTRinfr

jt

+ Control

jt

(1)

OFDI

ijt

= SA

it

+ SA

jt

+ IntTRinfr

jt

+

DomTRinfr

jt

+ Control

jt

(2)

where subscripts i, j and t define home country, host

country and time, respectively, OFDI represents

bilateral outward FDIs, MA represents the market

access, SA represents the supplier access, IntTRinfr

is our measure of international transportation

infrastructure, DomTRinfr is our measure of domestic

transportation infrastructure and Control is a vector of

control variables considering different aspects of host

countries' global competitiveness.

3.2 Data and Methodology

We conduct our study on a heterogeneous panel of

outward bilateral FDI stocks, including a wide variety

of developing and developed countries. Due to data

availability for our main variables, we focus on the

2008-2012 period. Regarding the links with outward

FDs, our main variables of interest are the market

access and transportation infrastructure, but we also

consider time fixed effects and several destination

country specific variables, to control for different

aspects of host countries global competitiveness, such

as availability of human capital, governance,

macroeconomic environment.

We choose bilateral outward FDI stocks as our

dependent variable rather than inward FDI, given that

the location decision comes from origin countries not

destination ones. Also, the literature on outward FDI

determinants is a lot scarcer than the one on inward

FDI determinants and it deals especially with cross

section data (mostly BRICS countries) rather than

panel data (Chou, Chen & Mai, 2011; Zhang & Daly,

2011; Wang, Hong, Kafouros & Boateng, 2012;

Anwar & Mughal, 2012). Regarding the market and

supplier access, we follow Redding and Venables

(2004) and compute these measures. Interestingly,

this measure of market/supplier access allows

considering at the same time countries’ market size,

their integration into world markets, trade costs as

well as unobserved heterogeneity via home and host

country fixed effects. As a proxy for international

transportation infrastructure, we take maritime

transportation. As a proxy for domestic transportation

infrastructure, we take rail transportation. If maritime

transportation appears as an obvious choice for

international transportation, Redding and Turner

(2015) shows that, in a rather heterogeneous sample

of developed and developing countries, rail appears

as the preferred mode for domestic transportation in

terms of ton kilometres. Also, in Europe, over the

period 2007-2016, around 55% of the rail freight is

national freight, with countries like the United

Kingdom, Turkey or Portugal approaching even 80 to

90% (author’s calculation based on Eurostat data).

For maritime transportation, we use UNCTAD’s

bilateral index for liner shipping connectivity (LSCI).

This very interesting measure of maritime

transportation includes 5 components, considering

the transportation capacity as well as the competition

on services connecting two countries. Finally, we add

control variables considering host countries’ global

competitiveness in terms of human capital,

governance, macroeconomic environment. Table 1

summarizes variables, data and sources.

Consequently, our equations to be estimated become:

OFDI

ijt

= MA

it

+ MA

jt

+ LSCI

ijt

+ RAIL

it

+

Control

jt

(3)

OFDI

ijt

= SA

it

+ SA

jt

+ LSCI

ijt

+ RAIL

it

+

Control

jt

(4)

Transportation Infrastructure and Market and Supplier Access: How Do They Shape Foreign Direct Investment?

91

Table 1: Data and sources.

Variable Data Source

OFDI Bilateral outward FDI UNCTAD (US$ millions, stocks)

MA/SA Market/Supplier Access Author’s calculation (index)

LSCI Bilateral liner shipping connectivity UNCTAD (index)

RAIL Rail lines density World Bank (total route-km/km

2

)

Control variables in host countries

SEC Secondary enrollment World Bank (units)

CORRUPT Corruption Index Transparency International (index)

UNEMP Unemployment rate World Bank (% of total labour force)

(a) (b)

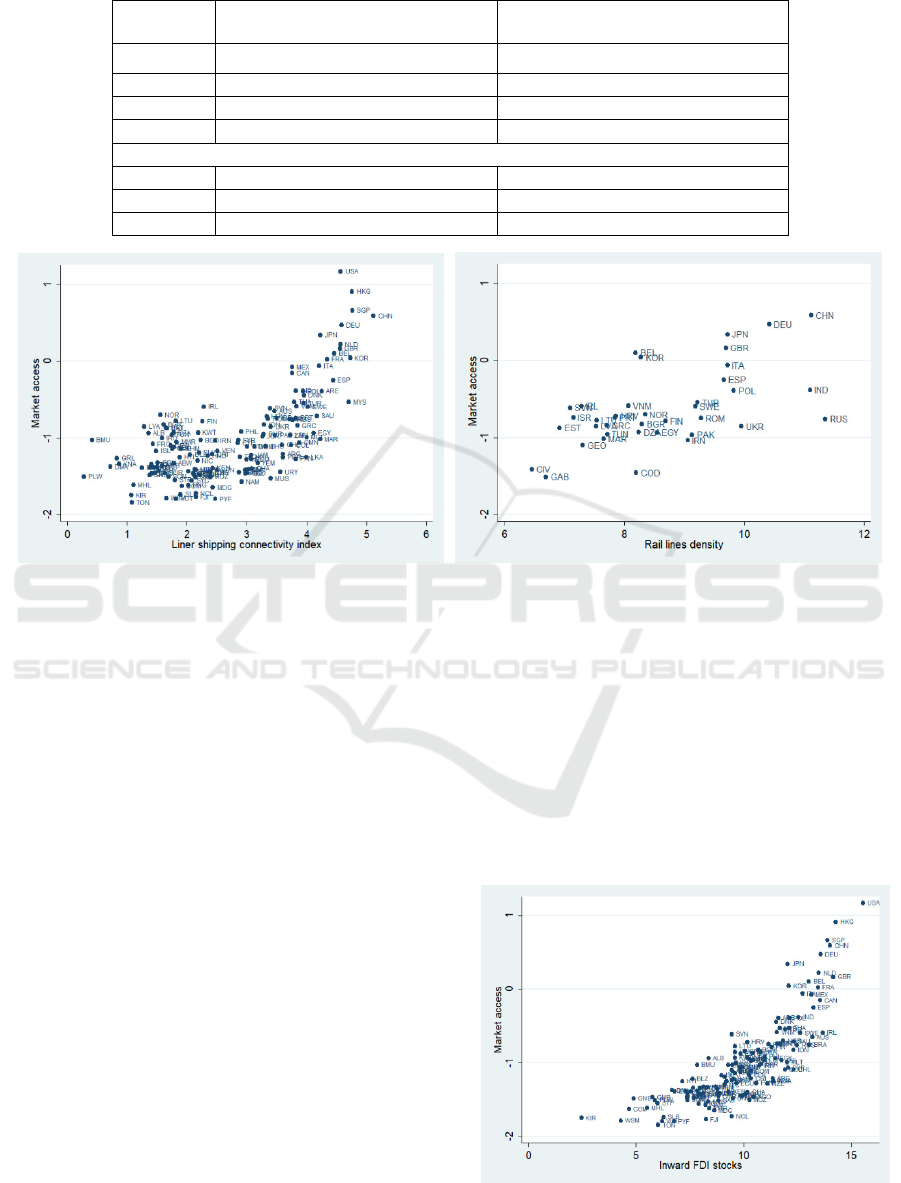

Figure 1: Transportation infrastructure and the market access (2015, log scale): (a) LSCI; (b) Rail lines density.

We follow a two-step analysis. In a first step,

given that there is no database for the market and the

supplier access for our time span, we are concerned

with their computation. Consequently, we follow

Redding and Venables (2004) and compute the

market and supplier access for all the countries in our

sample, between 2008 and 2012, with improved

econometric treatment allowing to take into account

the heteroskedasticity of bilateral trade flows,

traditionally used for this kind of computation. In a

second step, we use non-parametrical as well as

different parametrical estimators for gravity

equations, given that our dependent variable is the

bilateral outward FDIs. As one can already see in

Figure 1, the market access seems to be rather

positively related to the transportation infrastructure,

especially when it comes to the maritime

infrastructure.

One can notice the case of Belgium, Netherlands,

Hong Kong or Singapore, small economies, but with

very high market access, given their high openness

and integration into the world economy, whereas

China and the US show high market access especially

thanks to their very important domestic markets. Just

as transportation infrastructure, countries with high

market access also receive relatively higher FDI

stocks (Figure 2).

Studies on FDIs and the market access as defined

above are basically inexistent. Fugazza and Trentini

(2014) discuss the impact of the market access on

different types of FDIs, but their measure of the

market access is based on tariffs, which could be

assimilated to a de jure measure. Our measure of

market access is a rather de facto one, given that it is

based on actual trade flows between countries.

Figure 2: Market access and FDI (2015, log scale).

FEMIB 2023 - 5th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

92

Vechiu and Makhlouf (2014) use Mayer’s (2009)

real market potential, a similar variable, but analyse

its impact on EU countries’ sectorial specialization in

production not on FDIs. Hering and Paillacar (2016)

and Fally, Paillacar and Terra (2010) compute this

measure of market access but use it to discuss

migration and wages respectively. Finally, Candau

and Dienesch (2017) compute and use this measure

of market access to discuss multinational companies’

location decision via count models (number of

foreign affiliates) instead of FDIs. To our knowledge,

the only notable contribution on the link between this

de facto measure of market access and FDIs is Vechiu

(2018).

3.3 The Non-Parametric Assessment

and Parametric Estimation

Strategy

In a preliminary analysis, we proceed to a non-

parametric analysis of our main variables of interest:

bilateral outward FDIs (OFDI), the market and

supplier access (MA and SA) of destination countries

and the transportation infrastructure of destination

countries (LSCI and RAIL). The Kendall’s rank

correlation (results available on request) shows us

positive statistically significant connections between

all our variables, with the international component of

transportation infrastructure (LSCI) relatively more

correlated with FDIs than the domestic one (RAIL).

Regardless of the development level of host

countries, lower transportation costs between home

and host countries as well as within host countries do

attract FDIs, especially when it comes to international

transportation. This also suggests evidence for export

platform FDIs, with home countries seeking to serve

third markets, including their own, from foreign

locations.

Before proceeding to the parametric estimations,

summary statistics and density analysis (results

available on request) show two main problems related

to our dependent variable: overdispersion and

heteroskedasticity. These are current problems

related to bilateral FDI data, which require quite

specific econometric treatment. As stated by Silva

and Tenreyro (2006, 2008), the heteroskedasticity

inherent to gravity equations could be dealt with by

using the Poisson Pseudo Maximum Likelihood

(Poisson PML) estimator.

The latter remains consistent even in the presence

of overdispersion when the dependent variable is

continuous. Furthermore, Head and Mayer (2014)

suggest using OLS, as well as Poisson and Gamma

PML as robustness checks. Also, economists are

often concerned with endogeneity coming from

reverse causality (here, especially market access and

infrastructure variables endogeneity) as well as the

omitted variables bias.

In gravity equations, reverse causality should not

be a significant problem, given that the dependent

variable is bilateral, while the independent ones are

not (Naughton, 2014; Head & Mayer, 2014): for

instance, FDI coming from one partner country

should not have a significant impact on the market

access of a country. However, as a robustness check

allowing to solve the problem of potential

endogeneity of the market access and the

infrastructure variables, we also run all our

regressions by replacing the variables with their

lagged variables (first lag). Finally, we tackle the

problem of omitted variables bias by considering

several control variables, while our MA and SA

variables also take into account origin and destination

country fixed effects. Time fixed effects are also

included in all our regressions to control especially

for the 2008-2009 global crisis. We follow Head and

Mayer (2014) and use the three suggested estimators

for comparison and robustness checks.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1 Direct Effects

Table 2 reports results for the estimation of (3), using

OLS, PPML and GPML. The results for the

estimation of (4) are available on request. Our results

remain rather robust regardless of the method used,

with the remark that all estimators perform globally

better with the market access than the supplier access.

PPML and GPML estimates are highly similar,

suggesting that indeed heteroskedasticity is a problem

and OLS estimates are unreliable. Transportation

infrastructure variables perform very differently, with

the bilateral maritime index having a very strong

positive impact on OFDIs, whereas the rail

transportation impact is mostly non-significant. The

impact of the bilateral LSCI is very strong and very

significant as compared to most other variables,

confirming the previous non-parametric results and

especially in estimations taking into account the

supplier access. Consequently, multinational

companies seek foreign locations with high market

potential and goods access to suppliers, as well as

good connections to the home market: foreign

locations are more attractive if they allow exporting

back to the home market relatively cheaper and at the

same time supplying more easily foreign affiliates

Transportation Infrastructure and Market and Supplier Access: How Do They Shape Foreign Direct Investment?

93

Table 2: Transportation infrastructure, market access and FDI.

Dependent variable OFDI

ij

OLS PPML GPML

LnMA

i

0.998*** 1.243*** 0.946***

(-0.113) (-0.14) (-0.11)

LnMA

j

0.485** 1.336*** 0.520**

(-0.199) (-0.237) (-0.202)

LnLSCI

ij

2.321*** 1.815*** 1.822***

(-0.273) (-0.274) (-0.238)

LnRAIL

j

-0.036 -0.269*** -0.016

(-0.068) (-0.068) (-0.072)

LnSEC

j

0.445*** -0.063 0.244***

(-0.068) (-0.091) (-0.062)

LnUNEMP

j

-0.057 0.186 0.123

(-0.101) (-0.122) (-0.098)

LnCORRUPT

j

1.949*** 1.544*** 1.678***

(-0.236) (-0.239) (-0.196)

Constant -0.315 7.474*** 3.830***

(-1.368) (-1.563) (-1.052)

Time fixed effects yes yes yes

Obs 1,355 1,458 1,458

R

2

0.377

Robust standard errors in parentheses

*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

with home inputs. Corruption also stands out as a

powerful FDI determinant, with multinationals being

attracted to foreign location with low corruption

levels, as already highlighted in the literature (Candau

& Dienesch 2017; Vechiu 2018).

We are however concerned with the possible

endogeneity of some variables especially the

market/supplier access and the bilateral LSCI,

therefore we replicate the estimations by replacing all

independent variables with their first lag. Results do

not change significantly and are available on request.

4.2 Indirect Effects

As emphasized by Martin and Rogers (1995), the

impact of transportation infrastructure on FDIs might

depend on countries’ level of richness. Consequently,

we re-run all our regressions by integrating

interaction terms between transportation

infrastructure variables and the market/supplier

access (we add LnLSCI

ij

× LnMA

j

.and LnRAIL

j

×

LnMA

j

in (3) and then, LnLSCI

ij

× LnSA

j

and LnRAIL

j

× LnSA

j

in (4)). We take the market/supplier access

as a proxy for countries’ level of richness, given that

they are highly correlated (Redding & Venables,

2004; Mayer, 2009). Results for the regressions

taking into account the market and the supplier access

are available on request. Following the same

reasoning as in sub-section 4.1, estimations have been

run replacing all covariates with their first lag. Results

are also available on request.

Estimations allow highlighting some interesting

findings, namely regarding rail transportation

infrastructure, which becomes highly significant both

independently and via the interaction term.

Interpreting railroads in host countries as a

detrimental factor for outward FDIs is rather

counterintuitive, but however, the interaction term

does support Martin and Rogers’ (1995) view. While

estimation results allow reading the statistical

significance of the estimated coefficients, they are

less straightforward to interpret. Consequently,

Figure 3 presents the predictive margins for high and

low MA/SA in host countries. More precisely, in rich

host countries (high MA/SA), improving a poor rail

infrastructure has a negative impact on FDIs getting

in the country. Then, as the rail infrastructure

improves, its impact becomes null. On the other hand,

in poor countries (low MA/SA), rail infrastructure has

a positive impact on FDIs getting in the country. The

impact is very small for poor rail infrastructure, but it

becomes higher and higher, as rail infrastructure

improves. Accordingly, improving local

infrastructure in poor countries is a way to attract

FEMIB 2023 - 5th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

94

(a) (b)

Figure 3: The impact of rail infrastructure on bilateral OFDIs, as a function of destination countries’: (a) MA; (b) SA.

FDIs, as suggested by Martin and Rogers (1995).

However, regarding their conclusion that improving

international infrastructure might lead to capital

leaving poor countries, we find limited proof:

maritime transportation might have a positive impact

on FDIs getting in countries with low SA, but a

negative one in countries with high SA. Thus,

improving access to foreign suppliers becomes a

substitute for the low SA, consequently reassuring

and attracting foreign investors.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The importance of transportation infrastructure and

transportation services for economic development

has already been highlighted in theoretical as well as

empirical research. Transportation supports mobility,

thus contributing to economic growth and shaping

location decisions of consumers as well as

companies. However, if and how it impacts FDI

decisions has been less analysed.

This paper fills this gap by showing how different

types of transportation infrastructure affect FDI

decisions. Based on the conclusions of NEG models,

we have shown that transportation infrastructure has

different impacts on FDI depending on its

international versus domestic reach as well as on

countries’ economic development. If maritime

infrastructure is shown to have a strong significant

impact regardless of countries’ economic

development, rail transportation seems to be more

beneficial to poor countries than to rich ones.

Consequently, especially on developing and

poorer countries, public policies regarding

transportation should focus on infrastructure

designed to improve access and mobility first of all

on a national and local level and then, more

sophisticated infrastructure that allows a better

connection with global markets.

Finally, this work opens up perspectives for future

research, in order to better understand the linkages

between transportation infrastructure, FDI and

market/supplier access. More recent and more

detailed data (sectorial FDI, other types of

transportation infrastructure) would help define more

precise policy recommendations.

REFERENCES

Anwar, A. I., & Mughal, M. (2012). Economic Freedom

and Indian Outward Foreign Direct Investment: An

Empirical Analysis. Economics Bulletin, 32(4), 2991-

3007.

Baldwin, R. E, Forslid, R., Martin, P., Ottaviano, G. I. P.,

& Robert-Nicoud, F. (Eds.).(2003). Economic

Geography and Public Policy. Princeton: Princeton

University Press.

Behrens, K., Gaigné, C., Ottaviano, G. I. P., & Thisse, J. F.

(2007). Countries, Regions and Trade: On the Welfare

Impacts of Economic Integration. European Economic

Review, 51, 1277-1301.

Blyde, J., & Molina, D. (2015). Logistic Infrastructure and

the International Location of Fragmented Production.

Journal of International Economics, 95, 319-332.

Candau, F., & Dienesch, E.. (2017). Pollution Haven and

Corruption Paradise. Journal of Environmental

Economics and Management, 85, 171-192.

Castellani, D., Lavoratori, K., Perri, A., & Scalera, V. G.

(2021). International Connectivity and the Location of

Multinational Enterprises’ Knowledge-Intensive

Activities: Evidence from US Metropolitan Areas.

Global Strategy Journal, 12(1), 82-107.

Chen, H., Gangopadhyay, P., Singh, B., & Chen, K. (2023).

What motivates Chinese multinational firms to invest in

Transportation Infrastructure and Market and Supplier Access: How Do They Shape Foreign Direct Investment?

95

Asia? Poor institutions versus rich infrastructures of a

host country. Technological Forecasting & Social

Change, 189.

Chou, K. H., Chen, C. H., & Mai, C. C.. (2011). The Impact

of Third-Country Effects and Economic Integration on

China’s Outward FDI. Economic Modelling, 28, 2154-

2163.

Fally, T., Paillacar, R., & Terra, C. (2010). Economic

Geography and Wages in Brazil: Evidence from Micro-

Data. Journal of Development Economics, 91, 155-168.

Fogel, R. W. (1962). A Quantitative Approach to the Study

of Railroads in American Economic Growth: A Report

of Some Preliminary Findings. Journal of Economic

History, 22(2), 163-197.

Fogel, R. W. (1964). Railroads and American Economic

Growth: Essays in Econometric History. Baltimore:

Johns Hopkins Press.

Fugazza, M., & Trentini. C. (2014). Empirical Insights on

Market Access and Foreign Direct Investment. Study

Series. UNCTAD. http://unctad.org/en/pages/Publica

tionWebflyer.aspxpublicationid=876. Accessed 23

February 2018.

Fujita, M., & Thisse, J. F. (2006). Globalization and the

Evolution of the Supply Chain: Who Gains and Who

Loses?. International Economic Review, 47(3), 811-

836.

Hanson, G. H., Mataloni, R. J., & Slaughter, M. J. (2005).

Vertical Production Networks in Multinational Firms.

Review of Economics and Statistics, 87(4), 664-678.

Head, K., & Mayer, T. (2014). Gravity Equations:

Workhorse, Toolkit, and Cookbook. In G. Gopinath, E.

Helpman & K. Rogoff (Eds.), Handbook of

International Economics. (pp. 131-195). Elsevier.

Hering, L., & Paillacar, R. (2016). Does Access to Foreign

Markets Shape Internal Migration? Evidence from

Brazil. World Bank Economic Review.

Hong, J. (2007) Transport and the location of foreign

logistics firms: The Chinese experience.

Transportation Research Part A, 41, 597-609.

Krugman, P. (1991). Increasing Returns and Economic

Geography. Journal of Political Economy, 99(3), 483-

499.

Markusen, J. R. (1995). The Boundaries of Multinational

Enterprises and the Theory of International Trade.

Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9(2), 169-189.

Markusen, J. R., & Maskus, K. E. (2002). Discriminating

Among Alternative Theories of the Multinational

Enterprise. Review of International Economics, 10(4),

694-707.

Markusen, J., & Venables, A. J. (1998). Multinational

Firms and the New Trade Theory. Journal of

International Economics, 46, 183-203.

Martin, P., & Rogers, C. A. (1995). Industrial Location and

Public Infrastructure. Journal of International

Economics, 39, 335-351.

Mayer, T. (2009). Market Potential and Development.

CEPII Working Paper. http://www.cepii.fr/CEPII/en/

publications/wp/abstract.asp?NoDoc=1584. Accessed

24 April 2017.

Naughton, H. T. (2014). To Shut Down or to Shift:

Multinationals and Environmental Regulation.

Ecological Economics, 102, 113-117.

Redding, S. J., & Turner, M. A. (2015). Transportation

Costs and the Spatial Organization of Economic

Activity. In G. Duranton, J. V. Henderson, & W. C.

Strange (Eds.), Handbook of Urban and Regional

Economics, (pp. 1339-1398). Elsevier.

Redding, S., & Venables, A. J. (2004). Economic

Geography and International Inequality. Journal of

International Economics, 62, 53-82.

Rose, L., Savage, C., Jenkins, A., & Fransman L. (2017).

The Failure of Transport Megaprojects: Lessons from

Developed and Developing Countries. Paper presented

at the Pan-Pacific Conference XXXIV: Designing New

Business Models in Developing Economies, Peru.

Saidi, S., Mani, V., Mefteh, H., Shahbaz, M., & Akhtar, P.

(2020). Dynamic linkages between transport, logistics,

foreign direct investment, and economic growth:

Empirical evidence from developing countries.

Transportation Research Part A, 141, 277-293.

Shahbaz, M., Mateev, M., Abosedra, S., Nasir, M. A., &

Jiao, Z. (2021). Determinants of FDI in France: Role of

Transport Infrastructure, Education, Financial

Development and Energy Consumption. International

Journal of Finance & Economics, 26(1), 1351-1374.

Silva, J. M. C. S., & Tenreyro, S. (2006). The Log of

Gravity. Review of Economics and Statistics, 88(4),

641-658.

Silva, J. M. C. S., & Tenreyro, S. (2008). Comments on

‘The log of gravity revisited’. http://personal.lse.ac.uk/

tenreyro/mznlv.pdf. Accessed on 26 April 2018.

Vechiu, N. (2018). Foreign Direct Investments and Green

Consumers. Economics Bulletin, 38(1), 159-181.

Vechiu, N., & Makhlouf, F. (2014). Economic Integration

and Specialization in Production in the EU27: Does

FDI Influence Countries’ Specialization? Empirical

Economics, 46, 543-572.

Venables, A. J. (1996). Equilibrium Locations of Vertically

Linked Industries. International Economic Review,

37(2), 341-359.

Wang, C., Hong, J., Kafouros, M., & Boateng, A. (2012).

What Drives Outward FDI of Chinese Firms? Testing

the Explanatory Power of Three Theoretical

Frameworks. International Business Review, 21, 425-

438.

Yeaple, S. R. (2003). The Role of Skill Endowments in the

Structure of U.S. Outward Foreign Direct Investment.

Review of Economics and Statistics, 85(3), 726-734.

Zhang, X., & Daly, K. (2011). The Determinants of China’s

Outward Foreign Direct Investment. Emerging Markets

Review, 12, 389-398.

APPENDIX

Albania, Algeria, Angola, Antigua and Barbuda, Argentina,

Australia, Bahrein, Bangladesh, Barbados, Belgium, Belize, Benin,

Bermudas, Brazil, Brunei, Bulgaria, Cabo Verde, Cambodia,

Canada, Chili, China, Colombia, Comores, Costa Rica, Côte

FEMIB 2023 - 5th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

96

d'Ivoire, Croatia, Cyprus, Democratic Republic of the Congo,

Denmark, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Egypt, El Salvador,

Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Estonia, Fidji, Finland, France, French

Polynesia, Gabon, Georgia, Germany, Ghana, Greece, Guatemala,

Guinea, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia,

Iran, Iraq, Ireland, Island, Israel, Italy, Jamaica, Japan, Jordan,

Kenya, Kuwait, Latvia, Lebanon, Liberia, Lithuania, Madagascar,

Malaysia, Malta, Marshall Islands, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mexico,

Moldova, Morocco, Mozambique, Myanmar, Namibia,

Netherlands, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Nicaragua, Nigeria,

Norway, Oman, Pakistan, Panama, Papua New Guinea, Peru,

Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Qatar, Republic of the Congo,

Romania, Russia, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Samoa, Saudi Arabia,

Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Singapore, Slovenia, Solomon

Islands, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, Sri Lanka, Suriname,

Sweden, Syria, Tanzania, Thailand, Togo, Trinidad and Tobago,

Tunisia, Turkey, Ukraine, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom,

Unites States, Uruguay, Vanuatu, Venezuela, Vietnam, Yemen

Transportation Infrastructure and Market and Supplier Access: How Do They Shape Foreign Direct Investment?

97