Getting Ready for the New Normal Way of Working: Using Business

Simulation Projects to Foster Work-from-Anywhere Skills

Ilenia Fronza

1 a

, Gennaro Iaccarino

2 b

, Sara Tosi

2

, Luis Corral

3 c

and Claus Pahl

1 d

1

Free University of Bozen/Bolzano, Bolzano, Italy

2

I.I.S.S. “Galileo Galilei”, Bolzano, Italy

1

ITESM Campus Queretaro, Mexico

Keywords:

Work-from-Anywhere (WFX), Soft Skills, K-12, High School, Business Simulation Projects.

Abstract:

While entering the post-COVID-19 pandemic phase, to define a new normal way of working, some companies

are transitioning toward a permanent WFX model, while others are combining WFX with colocated work

(i.e., hybrid work). Therefore, fostering WFX skills (usually classified as soft skills) in early-career students

becomes crucial; additionally, it can help reduce early school leaving. This work aims at understanding how

business simulation projects foster the WFX skills deemed crucial by industries. To this end, we conducted two

case studies involving high school students. The final questionnaire revealed that most participants evaluate

their WFX as fair or higher. Moreover, they believe that business simulation projects help in developing WFX

skills. Based on our results, we highlight recommendations for educational practice.

1 INTRODUCTION

Work-From-Home (WFH) and Work-From-

Anywhere (a.k.a. WFX or WFA) allow greater

autonomy in selecting spaces, times, and tools

(Choudhury et al., 2019; Sako, 2021). With the

world entering the post-COVID-19 pandemic phase,

WFH/WFX is becoming the “new normal” way of

working. Software companies have shown that they

can work remotely without significantly impacting

productivity (Smite et al., 2021b); additionally,

most software professionals would like to continue

WFH/WFX (Terminal, 2021). Based on these consid-

erations, some companies choose a permanent WFX

model (Drera, 2021). Other major companies, such

as Google and Apple, are pushing their employees

to return to the office (Kaplan, 2021); however,

they are going toward hybrid work, which is neither

pure distributed nor pure co-located. Therefore, it is

becoming clear that WFX will be integrated (at least

to some extent, in the case of hybrid work) into the

new normal way of working. Consequently, the job

market of the next future will demand more and more

WFX skills (Paasivaara et al., 2013; Prossack, 2020),

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0224-2452

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7776-7379

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9253-8873

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9049-212X

which are usually classified as soft skills (Matturro

et al., 2019).

Research shows a gap between the software in-

dustry and software engineering education (Oguz and

Oguz, 2019); for example, novices at Microsoft face

problems related to their lack of soft skills, such as

social and communication skills (Begel and Simon,

2008). Therefore, there is a need to train future soft-

ware professionals by developing soft skills (Capretz

and Ahmed, 2018) and, specifically, make future soft-

ware professionals capable of confronting the chal-

lenges of WFX by thriving in the “new normal way of

working”.

Working in a remote setting requires a combi-

nation of good collaboration infrastructure and sev-

eral WFX skills, i.e., a complete mindset of au-

tonomy, teamwork, collaboration, technological re-

sources, and understanding of goals (Fronza et al.,

2022b). Cultivating these traits early in their career

will give students the skills they need for the new

work environment. To this end, high school students

must be provided with courses featuring authentic ex-

periences: early exposure to WFX will let them em-

brace WFX practices, develop a good command of

the enabling technology, and fine-tune the necessary

skills (Fronza et al., 2022b).

Business simulation projects can enhance several

skills, such as time and strategy management, nego-

418

Fronza, I., Iaccarino, G., Tosi, S., Corral, L. and Pahl, C.

Getting Ready for the New Normal Way of Working: Using Business Simulation Projects to Foster Work-from-Anywhere Skills.

DOI: 10.5220/0011986100003470

In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2023) - Volume 2, pages 418-425

ISBN: 978-989-758-641-5; ISSN: 2184-5026

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

tiation, and decision-making (Asiri et al., 2017; Xu

and Yang, 2010). Moreover, they can be used as a tar-

geted intervention to prevent and counter explicit and

implicit early school leaving because of their connec-

tion with real life (European Commission, 2020).

This paper explores how prepared students feel

in the WFX skills deemed crucial by the industry

representatives interviewed in (Fronza et al., 2022a).

Moreover, we investigate the contribution (perceived

by students) that business simulation projects make

to developing WFX skills. To this end, we build on

our previous work (Fronza et al., 2022a) by reporting

the results of two case studies we conducted follow-

ing the same approach. We distributed a questionnaire

among the participants of the case studies presented in

this work and the case study in (Fronza et al., 2022a).

Results show that most students evaluate their WFX

as fair or higher. Moreover, they believe that business

simulation projects help in developing WFX skills.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows: Sec-

tion 2 introduces related work and Section 3 details

the research method. Results are reported in Section

4. Section 5 draws conclusions and suggests areas for

future work.

2 RELATED WORK

After its inception in the 1970s (Choudhury, 2021),

the advances in digital technology (e.g., desktop virtu-

alization and video chat platforms) (Sako, 2021) and

the collected evidence on performance benefits (e.g.,

(Bloom et al., 2015)) made Work-From-Home (WFH)

spread in several sectors in the 2000s, with several

companies moving toward greater geographic flexi-

bility. Then, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, em-

ployees were given more flexibility and autonomy in

choosing spaces, times, and tools; on the other hand,

they started having greater responsibility for accom-

plishing objectives at the pre-established times (Soft-

tek, 2020). This led to the introduction of WFX poli-

cies, which extend WFH (Softtek, 2020) in a way that

workers can organize their activities by combining

private and work life. WFX is based on trust between

employer and collaborators (Stamenova, 2021; Soft-

tek, 2020) and on employees’ ability to understand the

goal, select available resources (tools and time), col-

laborate with others, and deliver results (Smart Work-

ing Observatory, 2020).

The development of research about COVID-19

and its many impacts on work settings is an emer-

gent topic that continues to evolve. With this reality

in mind, we discuss a selection of works that walk

us through the future of WFX after the pandemic, the

changes in working routines and practices that WFX

has determined, and the skills needed to succeed in a

WFX setting.

WFX. It is becoming clear that WFX will not disap-

pear after the pandemic: employees express the de-

sire to continue with remote work (Buffer, 2021) re-

gardless of several factors (including age, education,

gender, earnings, and family circumstances), even ac-

cepting sizable pay cuts (Barrero et al., 2021). As

a result, some companies are choosing a permanent

WFX model (Drera, 2021). In contrast, others (Ka-

plan, 2021) are going in the direction of hybrid work

(i.e., a combination of remote and in-office work-

ing) (Sako, 2021), since offering customized working

styles seems to be effective in attracting talents (Kelly,

2021).

WFH determined several changes and novelties in

working routines and practices. Among the reported

changes, the daily rhythm of WFX is more flexible

and self-imposed (Smite et al., 2021a). Several issues

have been reported concerning WFX, including a re-

duced ability to unplug, loneliness, complex collabo-

ration and communication (Buffer, 2021; Adil et al.,

2022). Moreover, maintaining an organizational cul-

ture represents one of the main issues; in this regard,

one challenge is defining those activities that must

happen in-the-office to help maintain the organiza-

tional culture (Smite et al., 2021a).

Skills Needed to Succeed in a WFX Setting. The ex-

isting literature in Global Software Engineering (for

example, (Monasor et al., 2010; Casey et al., 2007;

Swigger et al., 2010; Christensen and Paasivaara,

2022)) identified specific (soft) skills needed to suc-

ceed in WFX settings, such as strong written commu-

nication, adaptability, focus, time management, col-

laboration, working in culturally diverged teams, and

using collaborative technologies (Paasivaara et al.,

2013; Prossack, 2020). Several ideas for training have

been proposed in the existing literature, but they are

mainly dedicated to a university environment (Mona-

sor et al., 2010). The focus is given to practical ex-

periences through which students can learn by doing

(Monasor et al., 2010; Christensen and Paasivaara,

2022).

In our previous work (Fronza et al., 2022a), we

identified the following WFX skills deemed crucial

by industry representatives:

• Self-Motivation: The ability to understand busi-

ness goals, establish personal goals, and work to-

ward them without being constantly driven.

• Communication: It is crucial to maintain a con-

stant communication, collaboration, understand

and share goals and progress toward achieving

them, and maintain the team morale.

Getting Ready for the New Normal Way of Working: Using Business Simulation Projects to Foster Work-from-Anywhere Skills

419

• Autonomy: The ability to learn autonomously, un-

derstand goals, and execute tasks without being

constantly driven.

• Time Management: The ability to manage time

and achieve goals regardless of the effort invested

and the adopted schedule.

• Curiosity: Ability to initiate action, having an ex-

ploring attitude towards uncertain or ambiguous

conditions.

• Endurance (a.k.a. Resilience): Ability to over-

come failure, deal with ambiguity and frustra-

tion, and be persistent and emotionally tempered

to work in isolation.

• Position Fit: Ability to alignment personal goals

with company goals.

This paper builds on (Fronza et al., 2022a) to

understand whether high school students have WFX

skills and if activities featuring authentic experiences

(such as business simulation projects) can enhance

WFX skills.

Skills to Prevent Early School Leaving. This multi-

factorial problem depends on social and economic

difficulties, learning difficulties, and the educational

environment. In Europe, the early school leaving rate

is measured using the Early Leaving from Education

and Training (ELET), which considers students who

have not been admitted to the next class and students

regularly enrolled but not attending (Baldassarre and

Sasanelli, 2020). The percentage of students who

dropped out in 2019 was 9.7% (Eurostat, 2022), with

a target set for 2030 of less than 9%.

Early school leaving has relevant social and eco-

nomic implications and is directly related to the rate

of unemployment and social exclusion. The Euro-

pean program foresees the monitoring of the educa-

tion and training sector by collecting data and ana-

lyzing the phenomenon’s trends across the EU and

in individual member states. Thanks to the heavy

investment and the monitoring network carried out

in recent years, another similar early school leav-

ing, which is primary for the students’ adult life, has

emerged: the so-called implicit early school leaving.

This phenomenon concerns students who, even after

finishing school, have not acquired the basic skills

to undertake a professional career. Therefore, these

students attended schools passively, wholly alienated

from knowledge and skills. PISA, an OECD program

for international student assessment (PISA, 2022), as-

sesses basic skills achievement by measuring 15-year-

olds’ ability to use their reading, mathematics, and

science knowledge and skills to tackle real-life chal-

lenges.

In this context, the acquisition of soft skills allows

students not only to enter the world of work more ef-

fectively but also to attend university with greater suc-

cess (Piacentini and Pacileo, 2019). Promoting WFX

(soft) skills at school leads to a twofold benefit. On

the one hand, it would make students more prepared

for the current job market, and on the other hand, it

would help reduce early school leaving.

3 METHOD

In this study, we will answer the following questions:

• RQ1. What WFX skills do students have?

• RQ2. Do business simulation projects contribute

to developing WFX skills?

To answer these research questions, we conducted

two case studies following our approach in (Fronza

et al., 2022a) (Section 3.1). Then, we distributed a

questionnaire among all the students who participated

in the case studies presented in this work and the case

study presented in our previous work (Fronza et al.,

2022a) (Section 3.2).

3.1 Case Studies

The study context consists of the following two busi-

ness simulation projects (Asiri et al., 2017; Xu and

Yang, 2010) conducted in February 2022 in two

fourth-year classes of a CS high school in Bolzano,

Italy.

• The first business simulation project involved

nine students (8 M, 1 F). The project simulated

seven working days in a financial services com-

pany. Teams had to develop an application that

monitors NASDAQ financial stocks through the

Yahoo finance API. Then, collected data were pro-

cessed by a telegram bot and sent to the company

clients.

• The second business simulation project in-

volved 11 (M) students. The project simulated

seven professional working days to implement a

client-server application to monitor a hardware

system and ensure remote maintenance, imag-

ining instruments underwater or in inaccessible

places.

Both the business simulation projects followed the

approach of (Fronza et al., 2022a), i.e., they emu-

lated, methodologically and practically, the typical

software industry environment (Corral and Fronza,

2018). Similarly to (Fronza et al., 2022a), students

were divided into two major areas: the technical and

the communication area (i.e., focusing on documenta-

tion, communication, and graphic/web layout). Each

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

420

area was coordinated by a leader and, when possi-

ble, was divided into smaller groups based on tasks.

As suggested in (Bacon et al., 1999) students worked

in self-selected teams that chose their leader. Each

leader interacted with others and the area leaders. To-

gether with the teacher, each team defined short-term

goals that the teacher and leaders regularly verified.

Based on weaknesses and threats reported by students

in the SWOT analysis in our previous work (Fronza

et al., 2022a), we have introduced the following ad-

justments:

• smaller working groups and fewer working days

to improve communication and individual work-

ers management;

• the teacher focused on planning effective and at-

tractive short-term goals;

• better organized WFX activities, with more de-

fined slots of co-located work (usually 3-4 hours

in the morning);

• more autonomy for WFX activities.

Similarly to the case study in (Fronza et al.,

2022a), we distributed the following online question-

naire throughout the process to monitor the WFX ex-

perience:

1. Did you (or your team) achieve the goals? [y/n]

2. Did you find it difficult to achieve the goals? [y/n]

3. Did you achieve the goals on time? [y/n]

4. Did you work better alone or with your team?

[alone; with my team]

5. Indicate the time slots of the day in which you

worked in remote way (WFX).

The questionnaire is slightly different with respect

to the one we used in the previous case study (Fronza

et al., 2022a). Indeed, in these two case studies, on-

site working hours were pre-defined; moreover, as

suggested by the SWOT in (Fronza et al., 2022a), we

focused on the timely achievement of goals.

3.2 Questionnaire

We distributed a final questionnaire among all the stu-

dents participating in the case studies presented in

this paper. Moreover, we distributed the same ques-

tionnaire among the participants of our previous case

study (Fronza et al., 2022a). The questionnaire aimed

to assess 1) how prepared students feel they are re-

garding the WFX skills and 2) the contribution (per-

ceived by students) that business simulation projects

make to developing WFX skills. In particular, we fo-

cused on the WFX skills deemed crucial by the in-

dustry representatives interviewed in (Fronza et al.,

2022a) (see Section 2). For each of these WFX skills

(except position fit, which was disregarded as it is un-

likely to be applicable in the context of a short-term

project), students were asked to answer the following

two questions using a five-point scale (from very poor

to very good):

1. How good is this skill in your case? [very poor,

poor, fair, good, very good]

2. How good was the business simulation project in

helping you develop this skill? [very poor, poor,

fair, good, very good]

At the end of the questionnaire, students could

leave comments and feedback in an open question.

We followed legal requirements and ethical codes of

conduct for child participation in research, such as

informed consent, voluntary participation, and con-

fidential data treatment (EU Agency for Fundamental

Rights, 2014).

4 RESULTS

All the objectives proposed at the beginning of both

case studies have been achieved; the proposed solu-

tions have been tested and work correctly. Similarly

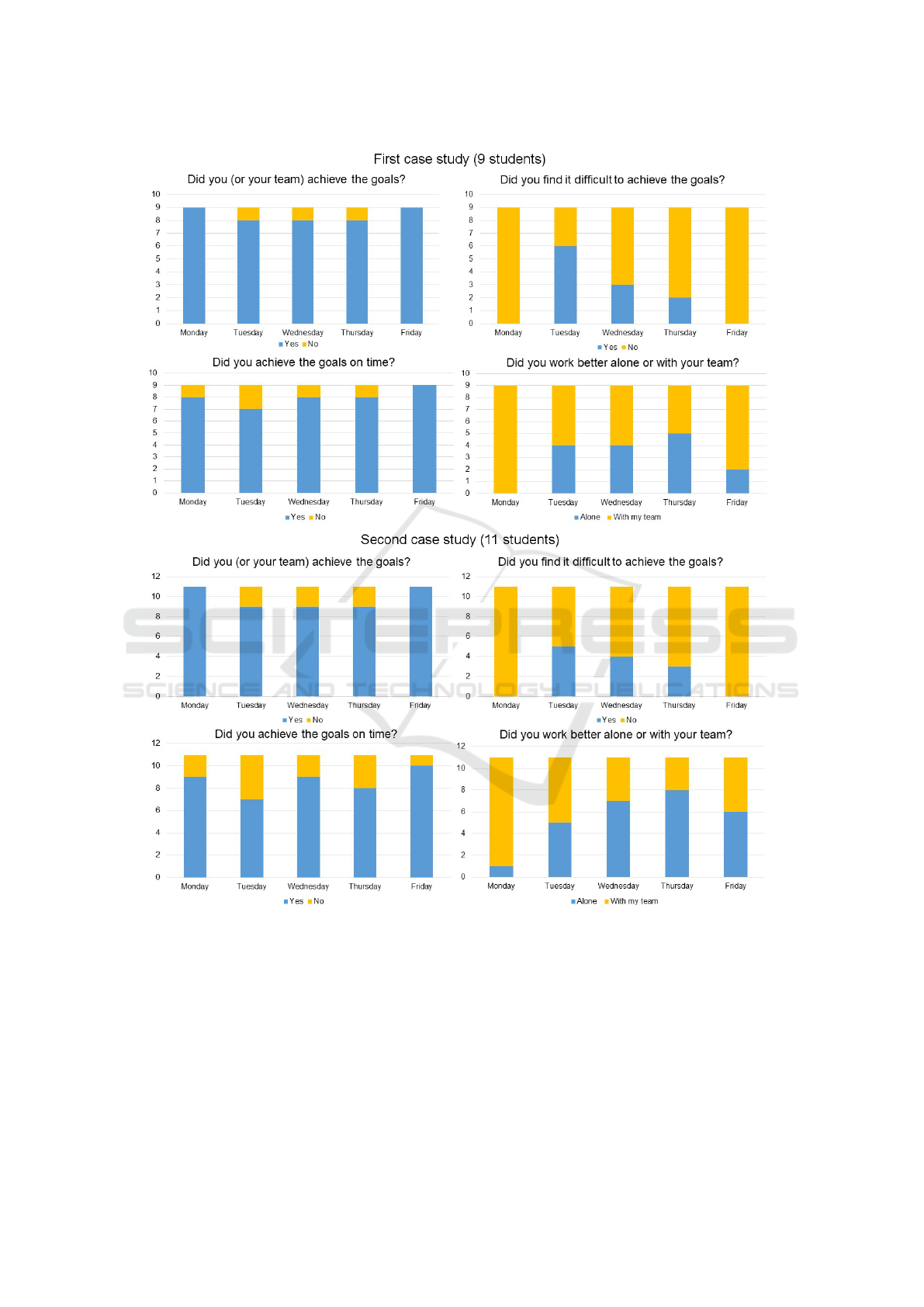

to what we reported in (Fronza et al., 2022a), Figure 1

shows that in both our case studies, most students re-

ported that they achieved daily objectives, mostly on

time, even though they encountered some difficulties.

Teamwork was appreciated, especially in the initial

and final parts of the projects; in the main phase of

the activities (i.e., once the main tasks and roles were

clear), students preferred to work independently.

The daily questionnaire also collected information

regarding the preferred time slots for WFX. As ex-

pected, in both case studies, there is limited WFX

in the morning (Figure 2); indeed, co-located work

has been encouraged in that part of the day. Con-

versely, when they could choose the working arrange-

ment (i.e., in the afternoon), students preferred WFX.

In the remainder of this section, we answer the

RQs by analyzing the data collected from the ques-

tionnaire distributed among the students participating

in the case studies presented in this paper and (Fronza

et al., 2022a). We collected 34/43 answers (79%), 23

from our previous case study (Fronza et al., 2022a),

and 20 from the case studies presented in this work.

RQ1. What WFX Skills Do Students Have? Figure

3 shows that most students evaluate fair or higher their

self-motivation (82.3%), communication (79.4%), au-

tonomy (88.2%), time management (73.5%), and cu-

riosity (79.4%).

In particular, nearly half of the students (44.1%)

consider their communication skills to be good, while

Getting Ready for the New Normal Way of Working: Using Business Simulation Projects to Foster Work-from-Anywhere Skills

421

Figure 1: Daily questionnaire of both case studies.

curiosity is the skill that gets the highest number of

preferences for “very good” (23.5%). Instead, most

students consider themselves weak on endurance.

RQ2. Do Business Simulation Projects Contribute

to Developing WFX Skills? According to the stu-

dents who participated in the case studies, busi-

ness simulation projects foster WFX skills. Indeed,

most students answered fair or above for most skills

(i.e., self-motivation 82%, communication 76.5%, au-

tonomy 76.5%, time management 79.4%, curiosity

73.5%). Only for endurance, 58.8% of students be-

lieve that the business simulation projects do not help

to acquire that skill. The analysis of the answers to

the open-ended question reveals that the length of the

business simulation project is considered too short to

acquire a complex skill, such as endurance/resilience.

The answers to the open-ended question offer in-

teresting insights. Students highlighted the pros and

cons of the business simulation projects, which some-

times seem to be curiously symmetrical regarding

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

422

Figure 2: Preferred time slots for WFX.

the same aspect. For example, several students em-

phasized that the activity effectively simulated a real

company/business context, allowing them to glimpse

the “real world” dynamics. Conversely, an almost

equal number of students remarked that the activity

would have been much more effective if carried out in

a company and not at school. This observation high-

lights that, even though carefully designed, a simula-

tion might still be perceived as a “fake workplace” de-

void of problems such as timing, relationships, envy,

and rewards.

Another relevant point regards the relationship

and communication between the various members of

the group. As a positive aspect, participants remarked

that business simulation projects enhance individual

talents in a team and foster management skills. On

the other hand, several students highlighted that some

team members’ lack of involvement/interest affected

the final result. However, everyone agrees on the char-

acteristics needed for successful teamwork (i.e., good

motivation, correct division of tasks, and attention to

roles), which should reflect everyone’s inclinations.

One student, in particular, highlighted the need for a

leader, “a charismatic person who brought the lazy

ones back to the right path. Without this figure, the

group sank quickly, groping in the dark without clear

objectives”.

As a positive aspect, students defined business

simulation projects as “stimulating and constructive”

and highlighted their ability to foster new skills with

respect to those required by “normal school practice”,

i.e., skills that “will be useful in the context of univer-

sity studies, as well as in the future world of work”

(e.g., problem-solving, autonomy, time management,

and communication). Nevertheless, negative aspects

of business simulation projects are reported as well.

For example, difficulties emerged in communication

and collaboration within the groups. In addition, the

activity should have been longer.

The following comment probably summarizes the

core characteristics of a business simulation project:

“It is an important activity for students; it brings

them closer to the world of work and challenges them.

It helps them develop new skills and collaborate to

reach a solution. Leaving students in complete auton-

omy is, in my opinion, the best way to let them grow”.

5 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

WORK

In this paper, we shed light on whether high school

students have WFX skills and if activities featuring

authentic experiences (such as business simulation

projects) can enhance WFX skills. Most of the stu-

dents who participated in our case studies (two in this

paper and one in (Fronza et al., 2022a)) evaluated as

fair or higher the majority of the WFX skills that are

deemed crucial by industries (e.g., self-motivation,

autonomy, curiosity). Moreover, they believe that

business simulation projects help in developing WFX

skills. On the other hand, students feel weaker in

terms of endurance and consider business simulation

projects too short to foster this skill.

Based on these results, business simulation

projects in high schools seem promising for pro-

moting the WFX skills deemed crucial by indus-

tries. Our study cannot inform whether students’ good

WFX skills are mainly due to the business simulation

project (i.e., we did not collect data on the entry level).

However, students clearly stated that the project con-

tributed to acquiring WFX skills.

Educators can use our results as a baseline to pro-

vide students with courses featuring authentic expe-

riences to prepare them for the “new normal way of

working”. Based on the results of this work, the main

suggestion emerging from this work is that business

simulation projects should be longer in time to allow

for the development of endurance. Second, educators

should focus on increasing the authenticity of these

experiences as much as possible so that students per-

ceive them as more similar to the professional setting.

We acknowledge that the work presented in this

paper may have limitations. In the following, we dis-

cuss them and propose directions for further research

to address these limitations. In this paper, we asked

students to self-assess their WFX skills. An objective

and validated tool for evaluating these skills would

strengthen the results. Therefore, we plan to focus

on this objective in the future. Larger samples are

needed to confirm and generalize the results and limit

the validity threats connected with the reliability and

validity of our instruments. Moreover, students’ back-

grounds might impact the results. Therefore, the ex-

perience should be repeated in other school contexts.

Finally, we plan to use these results and student com-

Getting Ready for the New Normal Way of Working: Using Business Simulation Projects to Foster Work-from-Anywhere Skills

423

Figure 3: Summary of the results of the questionnaire (34 respondents).

ments to make business simulation projects increas-

ingly similar to a professional context.

Preventing and countering explicit and implicit

early school leaving is a necessary priority. An ef-

fective way to do this is based on the configuration of

inclusive tools capable of welcoming, supporting, and

guiding the learning process of a plurality of students

(Baldassarre and Sasanelli, 2020). Based on the ac-

tivities presented in this paper, the teachers among the

authors agree that business simulation projects (with

WFX skills) can contribute to contrast implicit early

school leaving. Indeed, these projects make school

a permanent laboratory where skills are conveyed by

using practical activities similar to reality. In these

new educational contexts, students are encouraged

to express themselves, find solutions, and participate

with their abilities. In future work, we intend to inves-

tigate and measure the effectiveness of business sim-

ulation projects on contrasting implicit dispersion.

REFERENCES

Adil, M., Fronza, I., and Pahl, C. (2022). Software design

and modeling practices in an online software engi-

neering course: The learners’ perspective. In Interna-

tional Conference on Computer Supported Education,

CSEDU - Proceedings, volume 2, page 667 – 674.

Asiri, A., Greasley, A., and Bocij, P. (2017). A review of

the use of business simulation to enhance students’

employability (wip). In Proceedings of the Summer

Simulation Multi-Conference, SummerSim ’17, San

Diego, CA, USA. Society for Computer Simulation

International.

Bacon, D. R., Stewart, K. A., and Silver, W. S. (1999).

Lessons from the best and worst student team expe-

riences: How a teacher can make the difference. Jour-

nal of Management Education, 23(5):467–488.

Baldassarre, M. and Sasanelli, L. D. (2020). Implicit early

school leaving and inclusive curriculum: towards an

exploratory survey. Qtimes - Journal of Eduvation,

Technology and Social Studies, XII(4):240–250.

Barrero, J. M., Bloom, N., and Davis, S. J. (2021). Why

working from home will stick. Technical report, Na-

tional Bureau of Economic Research.

Begel, A. and Simon, B. (2008). Novice software devel-

opers, all over again. In Proceedings of the Fourth

International Workshop on Computing Education Re-

search, ICER ’08, page 3–14, New York, NY, USA.

ACM.

Bloom, N., Liang, J., Roberts, J., and Ying, Z. J. (2015).

Does working from home work? evidence from a

chinese experiment. The Quarterly Journal of Eco-

nomics, 130(1):165–218.

Buffer (2021). The 2021 state of remote work.

https://lp.buffer.com/state-of-remote-work-2020. Last

accessed: Jan. 2023.

Capretz, L. F. and Ahmed, F. (2018). A call to promote

soft skills in software engineering. Psychology and

Cognitive Sciences, 4(1):e1-e3.

Casey, V., Richardson, I., Moore, S., Paulish, D., and Zage,

D. (2007). Globalizing software development in the

local classroom. In 20 th Conference on Software En-

gineering Education & Training (CSEET’07), IEEE

Computer Society.

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

424

Choudhury, P., Larson, B., and Foroughi, C. (2019). Is it

time to let employees work from anywhere. Harvard

Business Review, 14.

Choudhury, P. R. (2021). Our work-from-anywhere future.

Defense AR Journal, 28(3):350–350.

Christensen, E. L. and Paasivaara, M. (2022). Learning soft

skills through distributed software development. In

Proceedings of the International Conference on Soft-

ware and System Processes and International Con-

ference on Global Software Engineering, ICSSP’22,

page 93–103, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Corral, L. and Fronza, I. (2018). Design thinking and ag-

ile practices for software engineering: an opportunity

for innovation. In Proceedings of the 19th Annual

SIG Conference on Information Technology Educa-

tion, pages 26–31.

Drera, S. (2021). Is work-from-anywhere (wfa) here to

stay? Linkedin, https://tinyurl.com/pv8xbtdd. Last

accessed: Jan. 2023.

EU Agency for Fundamental Rights

(2014). Child participation in research.

https://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2014/child-

participation-research. Last accessed: Feb. 2023.

European Commission (2020). A whole school approach

to tackling early school leaving. policy messages.

https://education.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/docu

ment-library-docs/early-school-leaving-group2015-

policy-messages en.pdf. Last accessed: Jan. 2023.

Eurostat (2022). Early leavers from educa-

tion and training by sex and labour status.

https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/bookmark/

05622de1-fe5a-43a1-858c-f603cf5734d6?lang=en.

Last update: September 2022.

Fronza, I., Corral, L., Iaccarino, G., Bartoli, L., and Pahl,

C. (2022a). Work-from-anywhere skills: Aligning

supply and demand starting from high schools. In

Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on

Computer Supported Education (CSEDU), volume 2,

pages 327–337, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Fronza, I., Corral, L., Wang, X., and Pahl, C. (2022b).

Keeping fun alive: an experience report on running

online coding camps. In 2022 IEEE/ACM 44th Inter-

national Conference on Software Engineering: Soft-

ware Engineering Education and Training (ICSE-

SEET), pages 165–175.

Kaplan, A. (2021). Musk says tesla staff can ‘pretend to

work somewhere else’ following leaked emails end-

ing remote work. https://tinyurl.com/yc4xayzh. Last

accessed: Jan. 2023.

Kelly, J. (2021). Smart companies will win the war for tal-

ent by offering employees uniquely customized work

styles. Forbes, https://tinyurl.com/3asxn9cy. Last ac-

cessed: Feb. 2023.

Matturro, G., Raschetti, F., and Font

´

an, C. (2019). A sys-

tematic mapping study on soft skills in software engi-

neering. J. Univers. Comput. Sci., 25(1):16–41.

Monasor, M. J., Vizca

´

ıno, A., Piattini, M., and Caballero,

I. (2010). Preparing students and engineers for global

software development: A systematic review. In 2010

5th IEEE International Conference on Global Soft-

ware Engineering, pages 177–186.

Oguz, D. and Oguz, K. (2019). Perspectives on the gap

between the software industry and the software engi-

neering education. IEEE Access, 7:117527–117543.

Paasivaara, M., Lassenius, C., Damian, D., R

¨

aty, P., and

Schr

¨

oter, A. (2013). Teaching students global soft-

ware engineering skills using distributed scrum. In

2013 35th International Conference on Software En-

gineering (ICSE), pages 1128–1137.

Piacentini, M. and Pacileo, B. (2019). How are pisa results

related to adult life outcomes? PISA in Focus, (102).

PISA (2022). Program for international student assessment.

https://www.oecd.org/pisa/.

Prossack, A. (2020). 5 must-have skills for remote work.

https://www.forbes.com/sites/ashiraprossack1/2020/07/

30/5-must-have-skills-for-remote-work/?sh=642d20d

f33c4. Last accessed: Jan. 2023.

Sako, M. (2021). From remote work to working from any-

where. Commun. ACM, 64(4):20–22.

Smart Working Observatory (2020). Smart work-

ing. https://www.osservatori.net/en/research/active-

observatories/smart-working. Last accessed: Jan.

2023.

Smite, D., Moe, N. B., Klotins, E., and Gonzalez-

Huerta, J. (2021a). From forced working-

from-home to working-from-anywhere: Two

revolutions in telework. [Online]. Available:

https://arxiv.org/abs/2101.08315. Last accessed: Jan.

2023.

Smite, D., Moe, N. B., Klotins, E., and Gonzalez-Huerta,

J. (2021b). Work patterns of software engineers

in the forced working-from-home mode. CoRR,

abs/2101.08315.

Softtek (2020). Smart working: Much more than

telework. https://softtek.eu/en/tech-magazine-

en/innovation-trends-en/smart-working-mucho-mas-

que-teletrabajo/. Last accessed: Jan. 2023.

Stamenova, A. (2021). Smart working: The

agility and flexibility enterprises need.

https://www.lumapps.com/blog/digital-

workplace/smart-working-definition-benefits-tools/.

Last accessed: Jan. 2023.

Swigger, K., Brazile, R., Serce, F. C., Dafoulas, G., Al-

paslan, F. N., and Lopez, V. (2010). The challenges

of teaching students how to work in global software

teams. In 2010 IEEE Transforming Engineering Edu-

cation: Creating Interdisciplinary Skills for Complex

Global Environments, pages 1–30. IEEE.

Terminal (2021). The state of remote engineering 2021 edi-

tion. Technical report.

Xu, Y. and Yang, Y. (2010). Student learning in business

simulation: An empirical investigation. Journal of Ed-

ucation for Business, 85(4):223–228.

Getting Ready for the New Normal Way of Working: Using Business Simulation Projects to Foster Work-from-Anywhere Skills

425