Designing a Career Exploration Corner for Children with Less Access to

Role Models

Fathima Assilmia and Keiko Okawa

Graduate School of Media Design, Keio University, Yokohama, Japan

Keywords:

Career Exploration, ICT for Rural Education, 360-degree Video.

Abstract:

Aspiration is substantial in children’s learning and career development. Unfortunately, the isolation of infor-

mation in rural areas left the children with a narrow vision of future careers. Utilizing the combination of

Information and Communication Technology (ICT) and analog learning methods, the project aims to broaden

children’s horizons and build a sense of connectedness between them and the world of work. Exploration

components and delivery methods were designed and validated with schoolchildren aged 9 to 13 who live in

Panglungan Village, Indonesia. Observation, survey, output analysis, and interview are combined to examine

the impact of the learning components and the program’s sustainability. The result shows that the learning

component designed also help promote aspiration in children in rural area. The research also emphasizes the

use of new media in non-formal learning like career exploration and the role of a learning center in rural areas.

1 INTRODUCTION

The question “what do you want to be when you grow

up?” is often asked of children. The answer could be

a job or the type of person they dream of in the future.

This answer comes from the information they are ex-

posed to up to that point. The information may come

from the closest people in their household, the peo-

ple they interact with daily, information from school,

television, etc. While these childhood aspirations may

not be the career they pursue when they are older, it is

believed to correlate to how they perceive careers and

impact their learning. Students with long-term goals

are more engaged in learning because they feel it is

a process to be someone they dream about and con-

tribute something to the world (Dweck et al., 2014).

This engagement in learning is also seen to positively

influence achievement (Martins et al., 2021).

Widening children’s awareness of the varieties of

careers can open more possibilities for them and help

them make better career decisions. Among many

sources that children can get career information from,

learning from the people in the working world may

help broaden their horizons (Chambers et al., 2018).

Learning directly from them could show the relevance

of learning, bring a different point of view and break

the stereotypes related to a certain job. However, chil-

dren who live in rural areas are lacking exposure to a

variety of career models as there are not that many

career examples available in the area. They also have

fewer encounters with what “people like them” can

be in their careers. This isolation of information may

narrow children’s vision of their future careers.

The existing efforts by the volunteers, in Indone-

sia for example, where work people from various

backgrounds visit elementary schools in rural areas

to share their profession with them (Inspirasi, 2016;

Pulau, 2014), are faced with some limitations in mo-

bility and access to the location (Bosma and Firdaus,

2017). This problem can be solved with Information

and Communication Technology (ICT), as many re-

search suggested (Chinapah and Odero, 2016; Poko-

rska, 2012; Ito et al., 2013). However, ICT solutions

for education in rural communities are often discon-

tinued because they are not designed based on local

needs. It is suggested that ICT solutions in rural ar-

eas should empower the local people (Warsihna et al.,

2013), combined with a network to the more extensive

community outside of the locality (Lowe et al., 2019).

Considering the infrastructure in the local area, figur-

ing out the right balance between the utilization of

technology and traditional learning method would be

crucial in ensuring the learning operation.

This research aims to design a sustainable ca-

reer exploration program for children with less ac-

cess to role models to promote their aspirations. To

deal with the disconnect between the world of work

and children in rural areas, the exploration of learn-

Assilmia, F. and Okawa, K.

Designing a Career Exploration Corner for Children with Less Access to Role Models.

DOI: 10.5220/0011987500003470

In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2023) - Volume 2, pages 229-236

ISBN: 978-989-758-641-5; ISSN: 2184-5026

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

229

ing components using immersive and analog media

for schoolchildren children ages 9-13 or grades 4-6

of elementary school was conducted. The delivery

method for sustainable practice in rural and disad-

vantaged areas was also explored. For this study, the

design was experimented with children and the com-

munity in Panglungan Village, a mountain village in

East Java, Indonesia. A combination of the quanti-

tative and qualitative evaluation was used to validate

the impact of the learning components in promoting

aspirations and the efficiency of the delivery method.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Career Exploration for Elementary

Schoolchildren

Career development programs often neglect the child-

hood stage, which is still far from the decision-

making period. In recent years, more people have

been interested in the importance of child career de-

velopment (Watson and McMahon, 2016). It is sug-

gested that at the elementary school level, the fo-

cus should be on raising aspirations and broadening

horizons instead of career advice (Chambers, 2018).

Gottfredson (1981) theorizes that the development of

children’s aspirations between 9 to 13 years old is

based on social valuation before evolving into unique

personal characteristics in the next stage (Gottfred-

son, 1981). This stage is the ideal age for children

to explore careers as a foundation of their career de-

velopment before developing their unique selves.

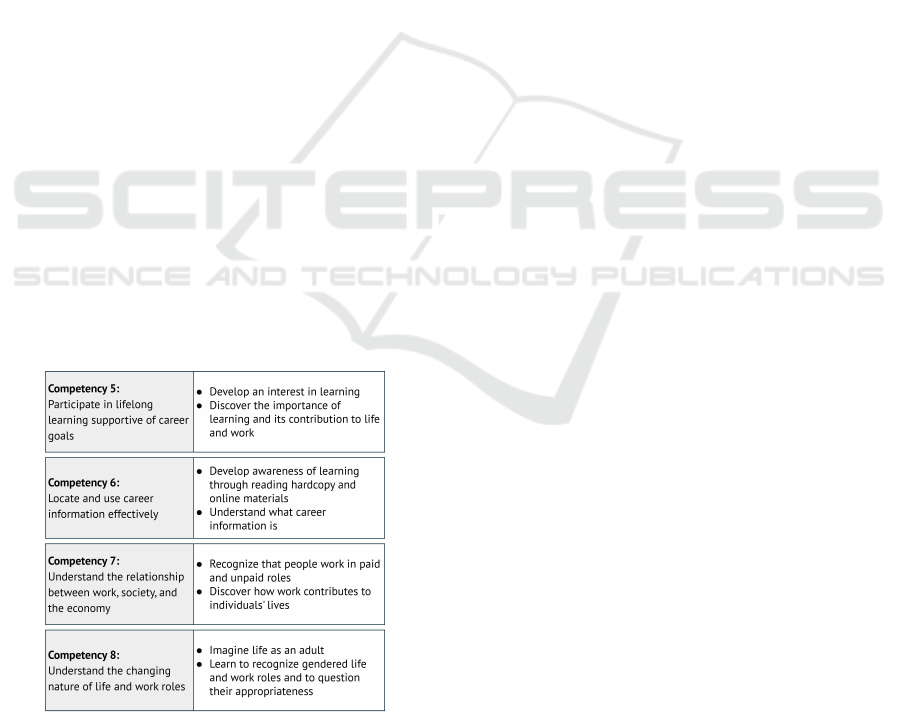

Figure 1: Early phases of career management competencies

in learning and work exploration area (Australia, 2010).

While “career” is closely related to paid jobs, it

embodies a person’s life roles and journey (Hodgetts,

2009). Learning about someone’s career is not lim-

ited to knowing their current job description but in-

cludes their learning and journey up to that point. An

Australian Blueprint for Career Development iden-

tified four competencies for learning and work ex-

ploration area (Australia, 2010). The competencies

were designed in five developmental phases, where

the Awareness and Exploring phases are the most suit-

able for elementary school children (Figure 1).

2.2 Combining Immersive Media and

Traditional Learning Method

Among many learning methods, Kolb’s Experiential

Learning Cycle (ELC), is an adaptive learning style

that emphasizes active contribution from learner (Mc-

Carthy et al., 2016). This learning style is based

on concrete experience, followed by reflective obser-

vation, abstract conceptualization, and active experi-

mentation, where learners grasp and deconstruct ex-

perience to gain knowledge (Illeris, 2018). The im-

plementation of ELC in virtual computer laborato-

ries helped learners gain a deeper understanding of

the subject matter (Konak et al., 2014). This study

also promoted peer learning to facilitate the reflection

and conceptualization stages of ELC. The application

of Experiential Learning or Active Learning with a

balance utilization of immersive and traditional me-

dia for children’s career exploration in rural areas is

explored in this study.

2.2.1 Immersive Learning Using 360 Video

Immersive media is beneficial in reintroducing some

of the crucial tools that exist in the traditional ed-

ucational space, like presence, immediacy, and im-

mersion (Bronack, 2011). Immersive Virtual reality

(IVR) as a learning source is believed to help de-

velop re-engagement to content over time (Makran-

sky and Petersen, 2021) and may also elicit a short-

term state of wanting to know more (Knogler et al.,

2015). Among many technologies categorized as im-

mersive, 360

◦

video is one of the more accessible

technologies as a mobile device, and a 3-DoF device

like Google Cardboard is sufficient to enjoy the ex-

perience. An example of the use of 360

◦

video in a

religious studies classroom resulted in students valu-

ing the experience, stating that it helped them deepen

their knowledge of religions and elicited feelings of

empathy toward other religions (Johnson, 2018).

Creating a learning experience using storytelling

in 360

◦

video requires different techniques compared

to the traditional two-dimensional (2D) video. Some

problems that could occur when creating educational

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

230

videos in 360

◦

video are related to the point of

view (POV) and attention (Kavanagh et al., 2016).

In a 360

◦

camera, the lens position represents the

viewer’s eyes. The placement and actors’ interac-

tion with the camera could give the illusion of inter-

action (Elmezeny et al., 2018). Because the viewer

can control their view, they might unintentionally lose

track of the main information when exploring the

spherical environment. It is suggested that having fo-

cused characters, a simple storyline, and using audio-

visual direction cues can help direct viewers’ atten-

tion (Elmezeny et al., 2018). But it is also emphasized

not to overly restrict viewers’ field of view to gain the

full advantage of 360

◦

video (Elmezeny et al., 2018).

2.2.2 Visual Journaling for Reflection Method

While immersive technology helps engagement in the

learning content, reflection as a way to extract mean-

ing from experience (Boud, 2001) could aid the com-

prehension process. Journaling is one of the practices

that is often used as a reflective method in learning

new material (Chang and Lin, 2014). Journaling is

believed to help us look more closely at a subject

and see things from an unexpected perspective (New,

2005). Furthermore, using it in its manual form en-

couraged students to be active learners and practice

critical thinking (New, 2005; Hash, 2021). Similarly,

a worldwide survey on primary school children’s as-

pirations used drawing to draw information from the

children (Chambers et al., 2018). Some of the rea-

sons that the report mentioned are the ability to help

children tell a better story, to encourage children who

are usually shy, and to avoid intimidation from other

people, especially teachers or adults.

2.2.3 Gamification in Children’s Learning

To make learning more exciting for children, gami-

fication, an approach using game features, is often

used (Faiella and Ricciardi, 2015). It is recommended

to use gamification in activities that include a repe-

tition to elicit interest (Faiella and Ricciardi, 2015).

Gamification in learning has been proven to benefit

the learning outcomes from a cognitive, motivational,

or behavioral perspective (Sailer and Homner, 2020).

Among many game elements used in children’s ed-

ucation, challenge, and achievement are some of the

most popular and present within (Nand et al., 2019).

2.3 Learning Center in Rural Areas

While ICT solutions can help bridge children with

the outside community, a physical center in the rural

area is deemed necessary (Svendsen and Lind, 2009;

Svendsen, 2013). Considering the difference in learn-

ing supporting tools available in every household,

a base or learning center that provides technology-

based solutions could expand the inclusivity of learn-

ing opportunities for the local people (Sharma, 2014).

Among many places available in the rural ar-

eas, the technology-supported physical space for non-

formal learning could be installed in existing Tele-

center (Yasya, 2020), public spaces like public library

(Svendsen, 2013), and mosque (Cheema et al., 2014),

privately owned space like coffee shop (Afifah, 2021),

and many other places depending on the characteristic

of the village.

3 DESIGN

3.1 Target User

The main target of this research was children ages 9-

13 or grades 4-6 of elementary school who live in ar-

eas with less access to role models. In these areas, the

transition from elementary to middle school is often

a crucial period for them to either continue school or

directly join the workforce, making the time before

this transition a critical period for intervention.

These areas usually have a homogenous commu-

nity with the main livelihood coming from the direct

use of natural resources like farming, fishery, min-

ing, etc. Even though many rural areas are already

provided with internet infrastructure, the stability and

access are not evenly distributed to every household.

Most children in these areas neither have individual

gadgets nor many adults who can guide them in ac-

cessing the internet productively.

3.2 Career Exploration Design

The Career Exploration components were designed

for children to explore various career journeys, see

how they impact people’s lives, and how the jobs can

relate to their daily lives. Through the preliminary ex-

plorations with children in Pramuka Island, Indonesia

(2017), Thien Binh Orphanage, Vietnam (2019), and

Panglungan Village, Indonesia (2021), different com-

binations of components were implemented and eval-

uated in each exploration (Figure 2).

Choosing an interest is a very personal and re-

peated process. The preliminary design results show

that individual exploration is the most efficient way

for children to explore based on their interests. The

children also enjoyed exploring the 360

◦

environ-

ment, especially the working process part. However,

verbal communication was not something they were

Designing a Career Exploration Corner for Children with Less Access to Role Models

231

Figure 2: Exploration component design process.

comfortable with. The use of visual journalling and

written communication may help the exploration pro-

cess. Additionally, the children desired interaction

with peers and their context, which was also deemed

necessary to increase their engagement.

There are four components to the career explo-

ration program. They are (1) Experience, (2) Reflect,

(3) Interact, and (4) Practice. Below is the improved

design of the components based on the lesson learned

from the preliminary research.

3.2.1 Component 1: Experience

In the Experience component, children experience

various people’s working lives in 360

◦

video format.

They choose one video content that they want to

watch each time. For this research, 13 video content

from five job categories were designed. The contents

are compiled in a Padlet (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Contents provided for the Experience component.

The purpose of the video content is to give a

workplace experience and tell an inspiring story of

a real working person. The video is created in the

first-person PoV around the workperson’s workplace,

where the workperson and children drive the story as

the main characters. Using audio and visual cues,

the viewer may have a sense of interaction with the

characters and environment in the video. The 7 to

10 minutes video contains one key point or statement

that guides the story. Based on that key point, the

story also includes (1) the career path of the workper-

son, (2) interesting working processes, (3) important

skills, (4) the social impact or value of the job, and (5)

an encouraging message from the workperson.

3.2.2 Component 2: Reflect

After watching the video, children internalize the ex-

perience. Initially, the reflection method was done

verbally, which did not work. Instead, using a visual

journaling method, children internalize their experi-

ence in two prompts (Figure 4). The prompt is a re-

flective drawing “If I were...”, where children imagine

how it would look like if they had the same profes-

sion as the workperson. The second part is reflective

writing “I should learn or do...”, where children con-

template the things that they can learn or do now to be

like the workperson.

Figure 4: Visual Journal template.

3.2.3 Component 3: Interact

Children interact with work people and peers through

comment writing and verbal communication in this

component. To the workperson, children write com-

ments or questions related to the video content or the

job. To their peers, they share their drawings from the

Reflect component.

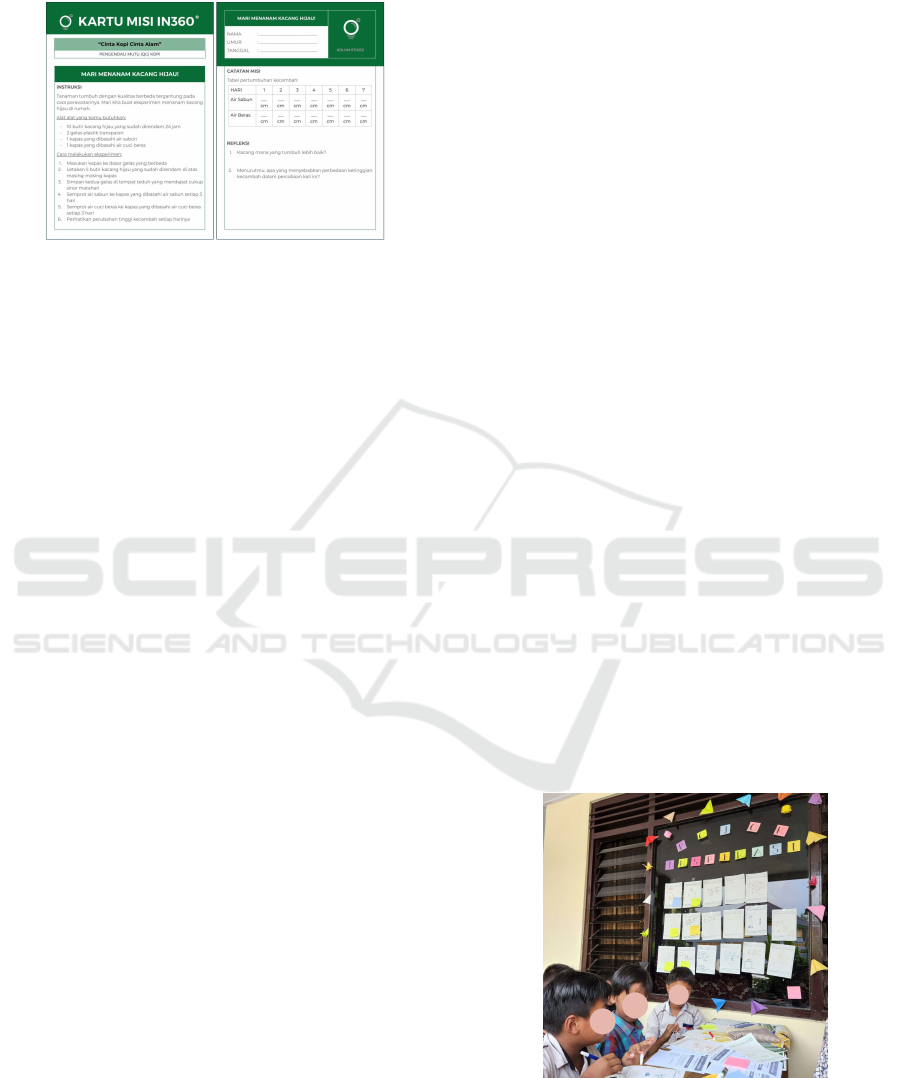

3.2.4 Component 4: Practice

The Practice component is when children exercise

how skills from the job can be transferred into daily

life. With the supervision of guardians at home, they

do a practical challenge following the Mission Card.

Each Mission Card is designed based on the video

content provided to the children. Each mission card

contains the details of the video, instructions for the

mission, an activity report column, and a reflection

column (Figure 5). The recommended duration for

each activity is around 2 hours across a 1-week time

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

232

frame. For every completed mission, they may re-

ceive a collectible reward.

Figure 5: Mission Card example.

3.3 Exploration Corner Design

To facilitate repeated exploration, children should

have a space to return to. Considering the diverse

availability of technology in every household, design-

ing a learning center that provides all the equipment

necessary for the exploration could ensure the inclu-

sivity of the program. This learning center, which

I call Exploration Corner, operates outside school

hours, where children can do the Experience, Reflect,

and Interact components with their peers. The mod-

ule for these three components is designed for 20 min-

utes, two children at a time. Therefore, for every hour

the Corner runs, it could accommodate 4-6 children.

The corner is supported by an internet connection, fa-

cilitated by a volunteer, and provides all the equip-

ment required for career exploration.

3.3.1 Corner Facilitation

The facilitator is someone from the local community.

The facilitator helps the children with the equipment

and time management during the activity. The fa-

cilitator should provide a safe space and encourage

children to express their thoughts throughout the ex-

ploration. They should be mindful not to do the ac-

tivity for children. Unlike how a classroom is usu-

ally conducted, there is no right or wrong answer

in the exploration process, so the facilitators should

not judge or give negative remarks about children’s

thoughts. Instead, a conversation based on chil-

dren’s opinions could expand their understanding of

the working world.

Supporting Materials. A program guideline and

supporting materials are provided to help the facili-

tator run the Exploration Corner. The materials in-

clude the 360

◦

video contents, corresponding Mission

Cards, and a visual journal template.

Equipment. A fundamental requirement to run the

Corner is a 360

◦

Video Viewing Set which includes

a 3DoF VR viewer, a gyroscope and accelerometer-

equipped smartphone, and an earphone. And last but

not least, colorful stationery and some stickers for the

Mission Card reward were also required.

4 IMPLEMENTATION

I implemented the Career Exploration and the Explo-

ration Corner in Panglungan Village. Panglungan is a

village located on the slope of Anjasmara Mountain

in East Java, Indonesia. The village is surrounded

by forest on three sides, and the only access to a

nearby village is through the north area of the village.

With the primary economic sector in agriculture, most

people here work as farmers or stay-at-home moms.

While 100% of the children in this village are regis-

tered in Elementary School or equivalent, the num-

ber of school enrollment continues to decrease even

though this area has school facilities with free tuition

up to High School. And only 10% of the students

in this area continue their study to higher education.

Most of them work as farmers or factory workers in

neighboring cities after discontinuing their studies.

The Career Exploration Corner was installed on

the front porch of Mr. A’s house. He was also the

facilitator for the corner. The house is near a Musholla

(prayer hall), where some children usually spend their

afternoon for religious education. (Figure 6). The

exploration ran for two cycles on July 2022. Each

cycle consists of four days, 2 hours each. A total of 43

children aged between 10 to 12 joined the exploration.

Participants were free to return to the second cycle as

they liked within the given schedule.

Figure 6: Career Exploration Corner at Panglungan Village.

Designing a Career Exploration Corner for Children with Less Access to Role Models

233

5 FINDINGS AND DISCUSSIONS

Through the Career Exploration implementation, the

impact of the activity on children’s aspirations us-

ing observation, survey, and output analysis methods.

Combined with real-time observation, a video camera

was set up to observe the participants during the ac-

tivities. A deeper analysis of communication and in-

teractions between participants was conducted using

video recording. After each activity, a post-activity

survey related to exploration was given out to partici-

pants. After excluding some data for consent and va-

lidity reasons, 69 data from the Corner Exploration

and 40 from the Practice component were used for

evaluation. Additionally, the efficiency of the corner

and its replicability were looked upon through obser-

vation during and after the installation of the corner,

along with interviews with the Corner Facilitators.

5.1 Promoting Aspiration in Children

5.1.1 Children Identify the Relationship

Between Learning, Life, and Work

The observation showed that children could explore

the video in all directions through the cues given

in the video. The result from the Reflect compo-

nent showed that children internalized the learning in

many different ways. Some identified the items in the

environment, while others interpreted what was being

said in the video and created their interpretation of

how they would look doing that job (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Children’s learning internalization.

Additionally, they reflected on what they should

do or learn to become like the person in the video.

The answers include general answers like “ I should

study hard” and “I have to study in college”; more

specific knowledge or skills to the job like “I should

draw better (to be a Game Illustrator),” “I should learn

how to edit video (to be a Video Designer),” “I have to

learn how to plant coffee seeds (to be a Coffee Quality

Controller)”; and attitudes or soft skills like “leader-

ship (to be a Creative Manager),” “discussion skill (to

be a Professor),” “experimenting (to be a Biotechnol-

ogist),” “discipline (to be an Animator),” and “helping

mom in the kitchen to be able to cook.”

5.1.2 Children Experience How Skills Can Be

Transferable

From the Mission Card result, it could be seen that

children experienced how the skills can be transfer-

able. One of the missions related to a professor’s job

was to gather data and retell the information (Fig-

ure 8). The children commented that they learned

about research skills, saying “I learned) to look for

information from the internet and interviewed the vil-

lage head.” The children also thought that the activity

helped them understand the vital attitude introduced

by the workperson. One of them commented “I have

to be brave to ask questions and know how to col-

lect data properly.” One of the parents’ feedback also

stated the activity’s benefit to children’s daily life. “I

am happy with this activity; my child has new experi-

ences and broader insights about everyday life.”

Figure 8: Children’s finished Mission Cards.

5.1.3 Positive Attitude Towards Their Future

After going through the activity, the children ex-

pressed their initial interest in the jobs. One of the

children wrote comments directed at the workperson,

saying “I want to be a professor”. The positive atti-

tude was also reflected in the survey result, where the

children were asked if they thought that they could be

like the workperson. The majority of them answered

“Yes” (Figure 9). The children also commented that

the activity motivated them to learn and pursue their

interests, stating “I gain experience and enthusiasm

to pursue my aspiration” and “I gain experience and

becoming more enthusiastic about going to school.”

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

234

Figure 9: ‘Do you think you can be like the person in the

video?’ (n=66).

5.1.4 High Interest to Explore More

According to the comments the children wrote for

work people, they showed curiosity toward the job.

They asked questions like “What do you usually do

in the office?”, “How to make it (video mapping)?”

etc. The parents also commented that the children

asked many questions at home, saying “... they asked

many questions; it forces us to think about giving log-

ical and reasonable answers.” From 39 children who

joined the first time, 28 children came on the sec-

ond cycle. 89.3% of them said they wanted to watch

another video. Most of them found the activity fun

and would like to know more about other professions.

The observation also showed the influence of peers

on children’s learning decisions, from choosing the

video to returning to the Corner for another cycle.

5.2 The Efficiency of Exploration

Corner

5.2.1 Strategic Location Encourages Interaction

Since the Career Exploration Corner location was

very close to the Musholla, many interactions were

observed during and after the running of the Corner.

During night prayer time, a group of children who

did not join the exploration visited the Corner asking

“What is this?”. Once they saw their friend’s name,

they called that kid to explain about the Corner. Some

kids also talked to the facilitator outside the explo-

ration hours and asked “when can we watch another

video again?”. After the validation period, two groups

of children visited the Corner and asked to do the ca-

reer exploration again.

5.2.2 The Technology Readiness

Due to the instability of the internet connection, the

video contents were downloaded using a Premium

YouTube account so that they could be played in high-

quality even without an internet connection.

5.2.3 Corner Facilitators Feedback

From the interview with Corner Facilitator, he under-

stood the project’s goal and stated that the guideline

was sufficient for them to comprehend the whole pro-

gram. He also had enough time to understand the

learning materials and prepare the logistics required.

However, he stated that he needs more experience to

help children who are shy to be more comfortable go-

ing through the exploration. He suggested that further

training in dealing with children with various charac-

teristics was necessary to facilitate better facilitation.

6 CONCLUSIONS

This research explored the design of a sustainable ca-

reer exploration program for children with less access

to role models to promote their aspirations. The val-

idation investigated whether the exploration compo-

nents help promote aspiration in children and whether

the Corner Exploration supports the program’s sus-

tainability. The result shows that new media could fa-

cilitate non-formal learning, like career exploration,

in rural areas. It also emphasizes the important role

of a learning center and facilitation. However, further

research on facilitator training needs to be explored

before moving forward to the service deployment.

Despite the promising result, the design is mainly

implemented in Indonesia. Replication in other re-

gions can increase the validity of the result. Addition-

ally, the long-term impact on children’s career deci-

sions could be evaluated later in the program. Lastly,

While we were able to adapt to the speed of the inter-

net during the implementation, it emphasized the need

to improve the infrastructure quality in rural areas.

REFERENCES

Afifah, N. (2021). personal communication.

Australia, M. M. (2010). Australian blueprint for career

development. Ministerial Council for Education, Early

Childhood Development and Youth Affairs.

Bosma, F. D. and Firdaus, M. (2017). Fenom-

ena Komunikasi Komunitas Kelas Inspirasi (Studi

Fenomenologi Social Movement pada Anggota Komu-

nitas Kelas Inspirasi Pekanbaru). PhD thesis, Riau

University.

Boud, D. (2001). Using journal writing to enhance reflec-

tive practice. New directions for adult and continuing

education, 2001(90):9–18.

Designing a Career Exploration Corner for Children with Less Access to Role Models

235

Bronack, S. C. (2011). The role of immersive media in on-

line education. The Journal of Continuing Higher Ed-

ucation, 59(2):113–117.

Chambers, N. (2018). Primary career education should

broaden children’s horizons. Accessed: 2022–06-08.

Chambers, N., Kashefpakdel, E. T., Rehill, J., and Percy, C.

(2018). Drawing the future: Exploring the career as-

pirations of primary school children from around the

world. London: Education and Employers.

Chang, M.-M. and Lin, M.-C. (2014). The effect of re-

flective learning e-journals on reading comprehension

and communication in language learning. Computers

& Education, 71:124–132.

Cheema, A. R., Scheyvens, R., Glavovic, B., and Imran,

M. (2014). Unnoticed but important: revealing the

hidden contribution of community-based religious in-

stitution of the mosque in disasters. Natural hazards,

71(3):2207–2229.

Chinapah, V. and Odero, J. O. (2016). Towards inclu-

sive, quality ict-based learning for rural transforma-

tion. Journal of education and research, 5(2/1):107–

125.

Dweck, C. S., Walton, G. M., and Cohen, G. L. (2014).

Academic tenacity: Mindsets and skills that promote

long-term learning. Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Elmezeny, A., Edenhofer, N., and Wimmer, J. (2018). Im-

mersive storytelling in 360-degree videos: An anal-

ysis of interplay between narrative and technical im-

mersion. Journal For Virtual Worlds Research, 11(1).

Faiella, F. and Ricciardi, M. (2015). Gamification and learn-

ing: a review of issues and research. Journal of e-

learning and knowledge society, 11(3).

Gottfredson, L. S. (1981). Circumscription and compro-

mise: A developmental theory of occupational aspira-

tions. Journal of Counseling psychology, 28(6):545.

Hash, P. (2021). Visual journaling as a method for critical

thinking in writing courses. Double Helix, 9.

Hodgetts, I. (2009). Rethinking Career Education in

Schools: Foundations for New Zealand Framework.

Careers Services.

Illeris, K. (2018). An overview of the history of learning

theory. European Journal of Education, 53(1):86–

101.

Inspirasi, K. (2016). Tentang ki. Accessed: 2022–04-29.

Ito, M., Guti

´

errez, K., Livingstone, S., Penuel, B., Rhodes,

J., Salen, K., Schor, J., Sefton-Green, J., and Watkins,

S. C. (2013). Connected learning: An agenda for re-

search and design. Digital Media and Learning Re-

search Hub.

Johnson, C. D. (2018). Using virtual reality and 360-degree

video in the religious studies classroom: An experi-

ment. Teaching Theology & Religion, 21(3):228–241.

Kavanagh, S., Luxton-Reilly, A., W

¨

uensche, B., and Plim-

mer, B. (2016). Creating 360 educational video: A

case study. In Proceedings of the 28th Australian con-

ference on computer-human interaction, pages 34–39.

Knogler, M., Harackiewicz, J. M., Gegenfurtner, A., and

Lewalter, D. (2015). How situational is situational in-

terest? investigating the longitudinal structure of situ-

ational interest. Contemporary Educational Psychol-

ogy, 43:39–50.

Konak, A., Clark, T. K., and Nasereddin, M. (2014). Using

kolb’s experiential learning cycle to improve student

learning in virtual computer laboratories. Computers

& Education, 72:11–22.

Lowe, P., Phillipson, J., Proctor, A., and Gkartzios, M.

(2019). Expertise in rural development: A conceptual

and empirical analysis. World Development, 116:28–

37.

Makransky, G. and Petersen, G. B. (2021). The cognitive

affective model of immersive learning (camil): a theo-

retical research-based model of learning in immersive

virtual reality. Educational Psychology Review, pages

1–22.

Martins, J., Cunha, J., Lopes, S., Moreira, T., and Ros

´

ario,

P. (2021). School engagement in elementary school:

A systematic review of 35 years of research. Educa-

tional Psychology Review, pages 1–57.

McCarthy, M. et al. (2016). Experiential learning theory:

From theory to practice. Journal of Business & Eco-

nomics Research (JBER), 14(3):91–100.

Nand, K., Baghaei, N., Casey, J., Barmada, B., Mehdipour,

F., and Liang, H.-N. (2019). Engaging children with

educational content via gamification. Smart Learning

Environments, 6(1):1–15.

New, J. (2005). Drawing from life: The journal as art.

Princeton Architectural Press.

Pokorska, A. (2012). Ict for inclusive learning: The way

forward. Eastern European Countryside, 18:169–176.

Pulau, K. I. J. (2014). About this group. Accessed:

2022–04-29.

Sailer, M. and Homner, L. (2020). The gamification of

learning: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology

Review, 32(1):77–112.

Sharma, T. (2014). Education for rural transformation: The

role of community learning centers in nepal. Journal

of Education and Research, 4(2):87–101.

Svendsen, G. L. H. (2013). Public libraries as breeding

grounds for bonding, bridging and institutional social

capital: The case of branch libraries in rural d enmark.

Sociologia ruralis, 53(1):52–73.

Svendsen, G. L. H. and Lind, G. (2009). Multifunctional

centers in rural areas: Fabrics of social and human

capital. Rural education in the 21st century. New York:

Nova Science Publishers.

Warsihna, J. W. J. et al. (2013). Pemanfaatan teknologi in-

formasi dan komunikasi (tik) untuk pendidikan daerah

terpencil, tertinggal dan terdepan (3t) [utilization of

information and communication technology (ict) for

education in rural, underdeveloped and outermost ar-

eas]. Jurnal Teknodik, pages 235–245.

Watson, M. and McMahon, M. (2016). Career exploration

and development in childhood: Perspectives from the-

ory, practice and research. Taylor & Francis.

Yasya, W. (2020). Rural empowerment through education:

Case study of a learning community telecentre in in-

donesia. International Journal of Modern Education

& Computer Science, 12(4).

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

236