Ear Training Applications in Music Education: Exploring Utilization,

Effectiveness, and Adoption Factors in France

David Andres Munive Benites

1 a

, Philippe Lalitte

1 b

and Victoria Eyharabide

2 c

1

IReMus Laboratory, Sorbonne University, Paris, France

2

STIH Laboratory, Sorbonne University, Paris, France

maria-victoria.eyharabide@sorbonne-universite.fr

Keywords:

Survey, Music Learning, Use of Technology, Music Education, Ear Training.

Abstract:

This study investigates the utilization of ear training applications in the context of music education in France.

Ear training is a crucial skill for musicians that involves the ability to identify and reproduce musical sounds.

Mobile applications are increasingly being used to support and enhance this skill. The study examines the

prevalence of ear training applications among music students and instructors, their perceived effectiveness,

and the factors that influence their adoption and use. It also explores the potential benefits and drawbacks

of integrating ear training apps into music education curricula. The data was collected through a survey of

125 students, as well as interviews with eight teachers and four developers. Results show that ear training

apps have potential benefits for music education in France, but are currently underutilized. While students

are willing to use them, teachers face challenges in finding apps that align with their pedagogical methods

and provide high-quality musical examples. Improved integration of ear training tools could be achieved by

focusing on music perception, memory, and metacognitive learning skills.

1 INTRODUCTION

In music, ear training refers to the process of devel-

oping and refining one’s ability to recognize and iden-

tify musical sounds, such as pitches, intervals, chords,

and rhythms, solely by listening to them. This skill is

essential for musicians of all levels and is frequently

taught in music schools and conservatories.

In this context, one of the most prevalent meth-

ods for training musical hearing is ”dictation,” which

refers to the process of listening to a piece of music

and then transcribing it by writing down the notes,

rhythms, and other musical elements that make up the

piece.

Computer technology, especially Computer-

Assisted Instruction (CAI), has been used for ear

training and dictation since the late 1960s(Peters,

1992). Within a decade, many universities in the

USA had adopted these tools, and a few commercial

options were available for domestic use. At the

professional level, the music industry, regardless of

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3540-0832

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6010-0658

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3775-1495

culture, was eager to use technology, which impacted

every aspect from recording to distribution.

Even though technology continues to drive trends

in the music industry, its pace in music education has

been slower(Spieker and Koren, 2021). Nonetheless,

the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent lockdowns

have affected the use of technology in the music and

ear training classroom. Therefore, this study analyzes

the current use of technology for musical ear train-

ing, focusing on the French higher education system,

students, and teachers.

2 EAR TRAINING APPS IN

HIGHER EDUCATION

INSTITUTIONS

Integration of ear training CAIs in higher education

has been analyzed since the first programs in the

1960s (Stevens, 1991; Peters, 1992). The adoption of

technology for higher music education has occurred

at different rates among countries. For example, in

the USA (Spangler, 1999), the UK (Upitis, 1983), and

Australia (Stevens, 2018), the use of CAIs in univer-

Munive Benites, D., Lalitte, P. and Eyharabide, V.

Ear Training Applications in Music Education: Exploring Utilization, Effectiveness, and Adoption Factors in France.

DOI: 10.5220/0012054200003470

In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2023) - Volume 1, pages 447-453

ISBN: 978-989-758-641-5; ISSN: 2184-5026

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

447

sities and conservatories has been well-documented

and analyzed. However, the adoption of technology

in other countries has had an irregular pace.

In 2020, Buonviri and Paney (Buonviri and Paney,

2020) conducted a study about the use of technology

in aural skills for Advanced Placement Music Theory

in the USA. They focused their survey on high school

teachers who pointed out that while technology can

offer additional practice opportunities and personal-

ized learning experiences for students, these advan-

tages may be reduced by limitations such as a lack of

access to technology and constraints of software pro-

grams. 91% of respondents incorporated technology

into their classrooms, primarily using websites during

class.

In Turkey, Demirtas¸ (Demirtas¸, 2021) conducted

a survey about university music students’ attitudes to-

wards technology after the 2020-2021 academic year,

during which the use of digital technologies predomi-

nated due to the pandemic. The researchers found that

attitude scores decreased after a year of e-learning in

all student populations.

In France, the authors Marie-Aline Bayon (Bayon,

2017) and Pascal Terrien (Terrien and Deveney, 2018)

have analyzed the broader topic of technology and

music education at all levels of instruction and its evo-

lution in recent years. Terrien found that despite the

challenges, teachers perceived the period of distance

learning as stimulating and satisfying due to peda-

gogical innovations and closer relationships with their

students and colleagues. He concluded that the inte-

gration of new technologies in teaching is not with-

out difficulty, and the use of digital tools should be

supported and involve stakeholders to affect teachers’

perceptions of learning, methods of collaboration, and

assessment. Bayon, on the other hand, has reflected

on the concept of a music school that integrates tech-

nology at all levels of instruction. The school uses

software for ear training, score editing, creation, and

recording. Bayon advocates for the integration of dig-

ital technologies in all music instruction levels.

Recent studies (De Berny et al., 2021; Biasutti

et al., 2022) have shown that the COVID-19 pan-

demic has accelerated the integration of technology

in education, specifically highlighting the benefits

of blended learning (Guppy et al., 2022). During

the pandemic, teachers focused on promoting stu-

dent success and adopted approaches such as cooper-

ative learning and individualized teaching. The over-

all findings of these studies indicate that online music

learning could be successful when teachers adapted

their content and developed personalized materials.

3 SORBONNE UNIVERSITY’S

STUDENT’S SURVEY

3.1 Background

In April 2021, a questionnaire was sent to undergrad-

uate and graduate students at the Sorbonne University

Musicology Department to inquire about the use of

digital tools for auditory and musical learning. The

objective of the survey was to understand the con-

ditions of using digital technology as an additional

tool for aural training at Sorbonne University. The

questionnaire aimed to explore students’ interests and

difficulties experienced in aural training, awareness

of the existence of digital learning tools, as well as

the most and least appreciated aspects of these tools,

among others.

3.2 Population

The number of responses to the questionnaire was

125, giving us a confidence level of 95% and a mar-

gin of error of 8.1% (see Table 1). It should be noted

that the questionnaire was only sent once to the stu-

dents’ email addresses. Women (71%) participated

more than men (29%) in the survey.

Most students (56%) were between 19 and 23

years old at the time of the survey. The most repre-

sented instruments among the students were the piano

(27.2%), voice (12.8%), violin (14.4%), cello (8.8%),

and flute (7.2%). The majority of students (49.6%)

had between 13 and 16 years of musical practice.

Sixty percent of students had one to three hours of

daily instrumental practice, and 48% had one to three

hours of group music practice. Additionally, 74.4%

of the students had studied in a specialized teach-

ing establishment (such as a Conservatoire au Ray-

onnement R

´

egional, P

ˆ

ole Sup

´

erieur d’Enseignement,

or CNSMDP), with 54.9% preparing or having pre-

pared a conservatory diploma. In France, most practi-

cal subjects are taught in conservatories while univer-

sities deliver Musicology (mostly theory oriented) de-

grees. Furthermore, 79.2% of students had five years

or more of ear training and music reading (solf

`

ege).

Table 1: Percentage of students surveyed by year.

% students N. students 1st year 2nd year 3rd year Master 1st Master 2nd

Total 839 33% 19.6% 17.6% 16.4% 13.2%

Survey 125 32.2% 20.8% 24% 11.2% 12.8%

3.3 Results

According to the survey results, 73% of students re-

ported experiencing difficulties in ear training. The

main causes of these difficulties were perception,

EKM 2023 - 6th Special Session on Educational Knowledge Management

448

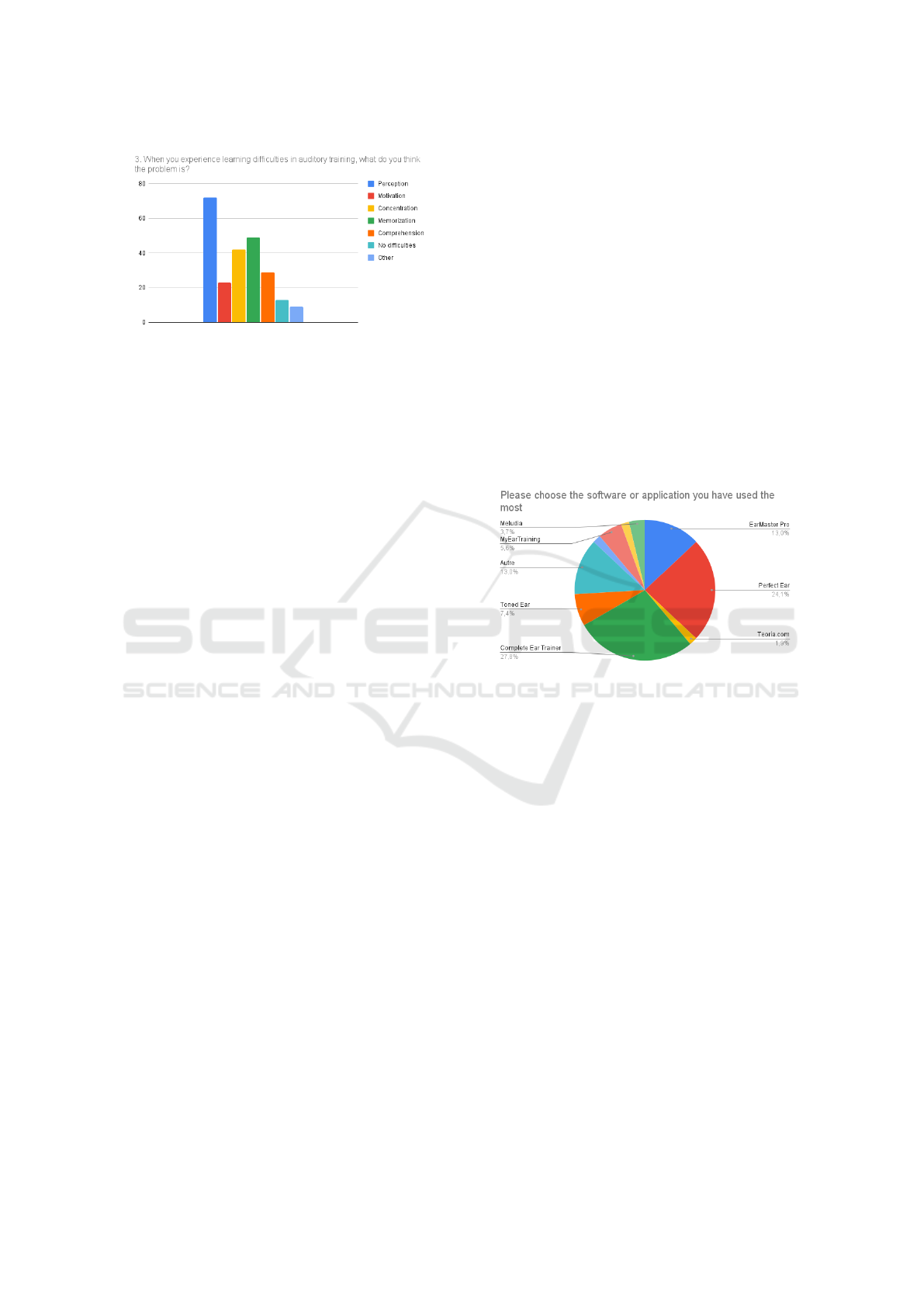

Figure 1: Learning problems felt by students.

memorization, and concentration (Figure 1). Al-

though 50% of students reported being aware of the

existence of applications for aural and musical learn-

ing, especially those that specialize in developing the

musical ear, only 59.7% of students reported receiv-

ing encouragement from their teachers to use learn-

ing applications. Furthermore, 56.5% of students

reported discussing learning applications with their

classmates. The majority of students (70.4%) used

learning applications on a smartphone. Nearly half

(48%) of students had used the applications for less

than a year, and 50% of students used the applications

”from time to time,” while 14.8% used them on a daily

basis. Of the students who used ear training applica-

tions, 81.4% reported that they were at most or mod-

erately motivated to study ear training, and 88.9% re-

ported being able to progress or moderately progress

thanks to these tools.

In terms of the most appreciated elements in the

applications, 55.6% of students found the learning

method to be the most favorable, followed by feed-

back on the answer. In contrast, the quality of the

sounds (37%) and visual design (31.5%) were the

least appreciated elements. The most common reason

for using the applications was ”to improve my school

results,” followed by ”to improve my musical knowl-

edge.” The main purpose of using the application was

to develop the musical ear, followed by learning har-

mony (called in France ”Music Writing”).

It is worth noting that the analyses of the survey

remain descriptive. The results did not provide sig-

nificant evidence to identify correlations among the

responses to predict behavior between variables. As

a result, a new survey is being developed to further

explore the needs of students in relation to the Sor-

bonne University’s ear training class. Nonetheless, it

is evident that the students find motivation and sup-

port in the ear training apps. They struggle primar-

ily with perception, memorization, and concentration

problems. The feedback and learning methods in the

apps are the most appealing elements to them, while

sound quality and visual design are the least favored.

3.3.1 Favourite Applications

The most used applications were:

• Complete Ear Trainer

• Perfect Ear

• EarMaster Pro

These applications have strong gamification fea-

tures, give immediate feedback on the response and

use drill type exercises for ear training. The gam-

ification aspects are score, time, ranking and statis-

tics. They offer exercises for intervals, chords, chord

inversions, scales, melodic dictations, chord progres-

sions. EarMaster Pro allows to sing or play the an-

swer, while on the other two the response is through

buttons. Additionally, EarMaster Pro has attracted the

interest of researchers, as evidenced by multiple stud-

ies (Liu, 2014; Wang, 2015).

Figure 2: Preferred applications.

Students declared having used and being familiar

with at least eighteen ear training applications (Fig-

ure 2). This data and the fact that at least 43% of

students mentioned having discussed with their col-

leagues about music learning apps shows that students

are interested, and look for music education tools.

The preferred applications, Complete Ear Trainer

and Perfect Ear are mobile phone applications, while

Ear Master Pro is a desktop application. In these ap-

plications the learning method was the main appreci-

ated feature, and the sound quality the least appreci-

ated, except in the case of EarMaster Pro where there

are some responses that point to the opposite.

The data in the current survey remains descriptive.

However, a more in-depth survey has been developed

and is currently being conducted at Sorbonne Univer-

sity and other universities in France, with the goal of

conducting a broader analysis.

Ear Training Applications in Music Education: Exploring Utilization, Effectiveness, and Adoption Factors in France

449

4 INTERVIEWS

4.1 Teachers

The active pedagogies, as described by Jacques-

Dalcroze, Willems, Orff, Kodaly, among others, have

had a significant impact on the teaching of solf

`

ege in

modern-day conservatories and universities in France

(Large, 2017). These pedagogical approaches typi-

cally rely on the musical experience of the student

as the primary means of learning (Prot

´

asio, 2022).

The active participation of the student in musical ex-

pression and personal reflection is central to these

methods. In 1977, influenced by this philosophy, the

French Ministry of Culture modified the approach to

teaching solf

`

ege from one that used abstract and seg-

mented musical elements to one that encouraged the

use of real musical examples (Large, 2017). This

change in approach is an essential element to con-

sider in understanding the reluctance to adopt most

available digital tools in formal music education.

In this study, we interviewed four conservatory

teachers, including two from Paris, one from Mar-

seille, and one from Tours, regarding their use of digi-

tal tools in the ear training class. One of them teaches

future ear training conservatory teachers. Two of the

teachers cited the technical nature of the drills and ex-

amples as the primary reason for not using ear training

apps. According to all four conservatory teachers, the

use of intervals, chords, or cadences in an uncontextu-

alized manner creates an artificial and unnatural envi-

ronment. Another point cited against the use of apps

was that the musical sounds tended to be poor in com-

parison to recordings of real instruments. Addition-

ally, the teachers emphasized the importance of the

human interaction of teacher feedback as a key ele-

ment in the progression of ear training, which they did

not consider positive to be automated. Although one

teacher acknowledged the potential for social interac-

tion with a community of learners, he was against the

use of gamification features, stating that the motiva-

tion to study should be intrinsic to the musical activi-

ties.

One conservatory teacher suggested that digital

tools could be beneficial if drills were presented in

relation to the historical evolution of musical con-

texts, highlighting how musical elements interact in

different ways, are played on different instruments,

and depend on the aesthetics of a particular style or

period. Another teacher expressed a desire for a tool

that could develop the student’s attention to a partic-

ular voice in a polyphony, where the student would

have to write the missing voice after listening to a

recording.

We also interviewed four university teachers at

Sorbonne University. In this university, the ear train-

ing and music analysis teachers have created a cur-

riculum that follows the content covered in the music

history class. In this way, they ensure an enhanced im-

mersion of students in specific styles. However, they

encounter the problem of a wide spectrum of levels

in aural skills, especially in the first year. They have

to constantly try different methods to help students

who are starting their musicology bachelors without

a strong ear training and music theory background.

These teachers are motivated to try digital tools to

support their work, but they cite similar conditions to

those stated by conservatory teachers regarding con-

textualization, the use of the voice or instruments, and

the quality of sounds.

Two advocates of digital technologies for music

education in France, Amandine Fressier and Marie-

Aline Bayon, were also interviewed. Despite hav-

ing different approaches, they share the objective of

using technology as a means of creative expression

to enhance the understanding of musical elements.

Fressier advocates for the use of open software, pri-

marily for musical notation and recording. In con-

trast, Bayon partners with platforms such as EarMas-

ter Pro or Soundtrap through her school, promoting

the integration of technology into a blended learning

format for music education. They are both prominent

advocates for the inclusion of digital technologies in

music education. According to both of them, the lack

of technology integration is due to inadequate instruc-

tion on these tools by teachers, budgetary constraints

from their institutions, and insufficient time to adapt

the tools to their usual teaching methods.

In summary The conservatory teachers cited poor

quality sound, lack of musical context, and the impor-

tance of human interaction and feedback as barriers

to the adoption of ear training apps, while one sug-

gested that such tools would be beneficial if presented

in relation to the historical evolution of musical con-

texts. The university teachers faced the challenge of

teaching a wide spectrum of levels in aural skills, but

were also motivated to try digital tools to support their

work. Finally, two advocates for digital technologies

in music education emphasized the importance of ad-

equate instruction, budgetary constraints, and insuffi-

cient time as reasons for the lack of technology inte-

gration in music education.

4.2 Developers

Various ear training software programs have been de-

veloped, including Meludia, EarMaster Pro, Com-

plete Ear Trainer, and the ear training research project

EKM 2023 - 6th Special Session on Educational Knowledge Management

450

BbMAT (Duret et al., 2021). These programs utilize

different platforms, including web, desktop, and mo-

bile apps. While BbMAT is free to use, the others are

available on subscription.

One of the most widely used programs is Ear-

Master Pro, which allows users to sing or play the

answer due to its pitch recognition feature, and in-

cludes scores of classical music and jazz for lesson

planning based on a real repertoire. However, the

use of computer-generated sounds is an issue that the

EarMaster team is working to address, as it limits

the program’s ability to provide a variety of instru-

ment samples. Meanwhile, Meludia takes a differ-

ent approach by focusing on ”fundamental musical

archetypes,” and Complete Ear Trainer is based on the

David Lucas Burge’s ”Perfect Pitch Ear Training Su-

perCourse” (Burge, 1981), which includes ear train-

ing drills on intervals, chords, scales, and dictation.

Both programs are considering the inclusion of real

repertoire in the future. BbMAT, on the other hand,

is specifically designed to train different aspects of

ear training, such as the identification of textures, tim-

bres, and emotional meanings in music, and has been

developed for use by cochlear implant users. Melu-

dia has also been used in studies for cochlear implant

users and incorporates timbral aspects in its training

path (Boyer and Stohl, 2022).

In interviews with the developers, it was noted that

budgetary constraints can limit sound quality and the

use of real musical examples, as well as the inclusion

of requests from different schools and teachers. De-

spite these challenges, developers continue to strive

for improvements and innovations in ear training soft-

ware programs.

5 DISCUSSION

The survey and the interviews with teachers and de-

velopers have allowed us to clarify the current state of

integration of digital technologies in the ear training

classroom, especially at the university level.

Although the survey did not show correlations, it

made clear that issues of perception, memory, and at-

tention are present. According to the literature, these

aspects are trainable, and could be addressed by spe-

cialized strategies (Blix, 2014). It is important to

note that students present these issues even though

most of them are not novice ear training/music theory

students. Therefore, a dedicated focus on attention

(Kraus and Chandrasekaran, 2010), memory (Mishra,

2004), and imagery (Zatorre and Halpern, 2005) can

improve the way students identify, conceptualize, and

use musical elements.

The interviews with the teachers revealed that they

would be willing to try digital tools in their ear train-

ing classes. In addition, they have ideas for software

that would be aligned with their methods. However,

problems like budget for these kinds of tools in con-

servatories, instruction on how to use and customize

the tools, and inappropriate pedagogical approaches

prevent larger integration. Some institutions have

managed to include these tools as part of their train-

ing; however, according to experts on digital integra-

tion in education (Bayon, Terrien, and Fressier), there

is still great potential in technology to tackle learning

problems.

In Sorbonne University (and probably in other

universities), poor basic knowledge of ear train-

ing/music theory can quickly become a handicap for

students in many subjects. The university is open-

ing doors to students who have not spent their previ-

ous years in music schools, conservatories, or who

do not come from families where music is prac-

ticed. Also, different musical backgrounds (interna-

tional students) and interests (electronic music pro-

duction and performance, influence of sound design)

can result in different levels of expertise regarding tra-

ditional ways to measure music literacy (such as dic-

tation and sight-reading). Therefore, we argue that

a way to provide more inclusive education would be

to offer tools that narrow the knowledge gap in these

specific areas and evaluate different aspects of musi-

cianship (Chenette, 2019).

The offer from apps could improve this landscape

by adding suggestions for learning by cognitive psy-

chology and pedagogy (Karpinski, 2000; Butler and

Lochstampfor, 1993). Instead of focusing only on

drills, it would be beneficial if they include contex-

tualized exercises and use their capabilities to further

interaction with musical content. The use of metacog-

nitive strategies (Blix, 2014) and singing (Fine et al.,

2006) can greatly benefit struggling students (Wash,

2019). They would also appeal more to teachers and

institutions if they could provide deeper levels of cus-

tomization (provided that they can guarantee teacher

training). We agree with the study of Cheng and

Leong (Cheng and Leong, 2017) in which they ad-

vocate for a better dialogue between software devel-

opers and ear training teachers. We believe that better

ICT instruction for teachers and the search for feed-

back by developers can have a positive impact on the

outcomes for all involved actors.

Ear Training Applications in Music Education: Exploring Utilization, Effectiveness, and Adoption Factors in France

451

6 CONCLUSIONS

Ear training apps are available in abundance on the

market, but unfortunately, they have not been ade-

quately utilized in formal music education in France.

However, students are willing to use these apps to

supplement their instruction, and many of them have

seen considerable benefits. Ear training and solf

`

ege

teachers, particularly those from younger generations,

are enthusiastic about incorporating digital tools to

enhance their lessons. However, in some cases, teach-

ers face the challenge of selecting from numerous

apps that do not fully align with their pedagogi-

cal approaches. The obstacles hindering the use of

these apps include inadequate musical examples, poor

sound quality, incomplete musical nuances, and high

costs for students. Some developers are working to

address these concerns and meet the needs of educa-

tors. We assert that the integration of ear training tools

can be improved by providing real musical examples

and focusing on training music perception, memory,

and metacognitive learning skills.

7 DATA AVAILABILITY

The data that support the findings of this study are

available from the corresponding author, [DAMB],

upon request.

REFERENCES

Bayon, M.-A. (2017). R

´

evolution num

´

erique et enseigne-

ment sp

´

ecialis

´

e de la musique: quel impact sur les

pratiques professionnelles? L’Harmattan.

Biasutti, M., Antonini Philippe, R., and Schiavio, A.

(2022). Assessing teachers’ perspectives on giving

music lessons remotely during the covid-19 lockdown

period. Musicae Scientiae, 26(3):585–603.

Blix, H. S. (2014). Learning strategies in ear training. Au-

ral perspectives. On musical learning and practice in

higher music education.

Boyer, J. and Stohl, J. (2022). Meludia–online music train-

ing for cochlear implant users. Cochlear Implants In-

ternational, 23(5):257–269.

Buonviri, N. O. and Paney, A. S. (2020). Technology use

in high school aural skills instruction. International

Journal of Music Education, 38(3):431–440.

Burge, D. L. (1981). The Perfect Pitch Ear-training Super-

course. David L. Burge.

Butler, D. and Lochstampfor, M. (1993). Bridges unbuilt:

Comparing the literatures of music cognition and au-

ral training. Indiana Theory Review, 14(2):1–17.

Chenette, T. K. (2019). Taking aural skills beyond sight

singing and dictation. Engaging Students: Essays in

Music Pedagogy, 7.

Cheng, L. and Leong, S. (2017). Educational affordances

and learning design in music software development.

Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 26(4):395–407.

De Berny, C., Rousseau, A., and Deschatre, M. (2021). Les

usages du num

´

erique dans l’enseignement sup

´

erieur.

Technical report, L’INSTITUT PARIS REGION.

Demirtas¸, E. (2021). The effect of the covid-19 process on

the attitudes of music students towards e-learning1.

Bridging Theory and Practices for Educational Sci-

ences, 14:247–258.

Duret, S., Bigand, E., Guigou, C., Marty, N., Lalitte, P.,

and Bozorg Grayeli, A. (2021). Participation of acous-

tic and electric hearing in perceiving musical sounds.

Frontiers in Neuroscience, 15:558421.

Fine, P., Berry, A., and Rosner, B. (2006). The effect of

pattern recognition and tonal predictability on sight-

singing ability. Psychology of Music, 34(4):431–447.

Guppy, N., Verpoorten, D., Boud, D., Lin, L., Tai, J., and

Bartolic, S. (2022). The post-covid-19 future of dig-

ital learning in higher education: Views from edu-

cators, students, and other professionals in six coun-

tries. British Journal of Educational Technology,

53(6):1750–1765.

Karpinski, G. S. (2000). Lessons from the past: Music the-

ory pedagogy and the future. Music Theory Online,

6(3):1–6.

Kraus, N. and Chandrasekaran, B. (2010). Music training

for the development of auditory skills. Nature reviews

neuroscience, 11(8):599–605.

Large, L. (2017). Redonner du sens au cours de forma-

tion musicale aujourd’hui. Master’s thesis, CEFE-

DEM Auvergne Rh

ˆ

one-Alpes.

Liu, H. Y. (2014). Application of music software in college

professional music using. In Applied Mechanics and

Materials, volume 556, pages 6754–6757. Trans Tech

Publ.

Mishra, J. (2004). A model of musical memory. In Proceed-

ings of the 8th International Conference on Music Per-

ception and Cognition. Adelaide, Australia: Causal

Productions, pages 74–86.

Peters, G. D. (1992). Music software and emerging tech-

nology. Music Educators Journal, 79(3):22–63.

Prot

´

asio, N. (2022). Aproximac¸

˜

oes culturais nas peda-

gogias musicais de dalcroze, kod

´

aly, willems e orff.

Revista Musica Hodie, 22.

Spangler, D. R. (1999). Computer-assisted instruction in

ear-training and its integration into undergraduate mu-

sic programs during the 1998-1999 academic year.

Master’s thesis, Michigan State University.

Spieker, B. and Koren, M. (2021). Perspectives for music

education in schools after covid-19: The potential of

digital media. Min-Ad: Israel Studies in Musicology

Online, 18:74–85.

Stevens, R. S. (1991). The best of both worlds: An eclectic

approach to the use of computer technology in music

education. International Journal of Music Education,

(1):24–36.

EKM 2023 - 6th Special Session on Educational Knowledge Management

452

Stevens, R. S. (2018). The evolution of technology-based

approaches to music teaching and learning in aus-

tralia: A personal journey. Australian Journal of Mu-

sic Education, 52(1):59–69.

Terrien, P. and Deveney, G. (2018). L’int

´

egration du

num

´

erique dans l’enseignement: apprentissage musi-

cal, instrumental et vocal. L’Harmattan.

Upitis, R. (1983). Milestones in computer music instruc-

tion. Music Educators Journal, 69(5):40–42.

Wang, Y. A. (2015). Study on solfeggio teaching under midi

environment. Management, Information and educa-

tional engineering, page 469.

Wash, E. (2019). Using technology to enhance instruction

and learning in the music classroom. Master’s thesis,

Liberty University.

Zatorre, R. J. and Halpern, A. R. (2005). Mental con-

certs: musical imagery and auditory cortex. Neuron,

47(1):9–12.

Ear Training Applications in Music Education: Exploring Utilization, Effectiveness, and Adoption Factors in France

453