A Strategy for Structuring Teams Collaboration in University Course

Projects

Chukwuka Victor Obionwu

1 a

, Maximilian Karl

2

, David Broneske

3 b

, Anja Hawlitschek

1 c

,

Paul Blockhaus

1

and Gunter Saake

1 d

1

Otto-von-Guericke University Magdeburg, Saxony-Anhalt, Germany

2

Humboldt-University Berlin, Germany

3

German Centre for Higher Education Research and Science Studies, Hannover, Lower Saxony, Germany

Keywords:

Knowledge Transfer, Skill Acquisition, Interaction Analysis, Collaborative Platforms, Study Engagement,

Social Behavior, Team Assessment Strategy.

Abstract:

The increased demand in today’s work environment for individuals with diverse skill sets, fast skill acquisition,

and ability to collaborate is as a consequence of the rapidly evolving technological environments. Thus,

institutes of higher learning have increasingly adopted e-learning platforms, owing that one of the defining

aspects of these platforms is the capacity to facilitate collaborative engagement. This adoption has resulted

in curriculum changes, and the development of tools and further specialized platforms that are focused on the

acquisition and transfer of particular soft, and hard skill sets. One such specialized platform is Teams platform

of SQLValidator, a web-based interactive environment for learning, practicing, and acquisition of collaborative

problem-solving skills by way of projects centered around the Structured Query Language. In this paper, we

give insight into our platform, and the strategy we adopted to ensure the acquisition of SQL, and collaborative

skills. To assess its effectiveness, we monitored the activity and performance of our students on an SQL based

collaborative project. Our evaluation indicates that our strategy not only gave us practical insight into the

student level of SQL skill acquisition, and interaction, which is important for instructors, but is also proved

effective in facilitating the acquisition, and transfer of teamwork ethics and collaborative problem-solving skill

among students.

1 INTRODUCTION

The challenge, structure, and requirements of the

21st-century work environment have made the acqui-

sition of teamwork and collaborative problem-solving

skills indispensable (Sundstrom et al., 1990). This

is most evident in the information technology sec-

tor, where the work is often split into well-defined

subtasks to create complex tools. Ergo, it requires

a team of individuals with different backgrounds and

skill sets. Usually, the basis for this skill acquisition is

set during a person’s studies. Due to the recent move

to online learning in most institutions of higher edu-

cation, curriculum administrators and developers are

resorting to online environments that can stimulate

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9109-5866

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9580-740X

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8727-2364

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9576-8474

task engagement, team collaboration, task reflection,

and the acquisition of teamwork skills. Early imple-

mentations of team-based learning showed that col-

laborative problem-solving within small groups was

effective in stimulating active learning (Michaelsen

et al., 2004; Gomez et al., 2010). As observed

in (Michaelsen et al., 2004), team members assumed

specific roles in an effort to efficiently solve the as-

signed tasks. While most team members were not ef-

fectively suited for the assigned roles, team leaders

took it upon themselves to ensure their peers’ learn-

ing. This challenge of fitting team members into de-

fined roles still persists in recent traditional lecture

settings (Michaelsen and Sweet, 2011).

Most recent efforts at orchestrating team collabo-

ration involved platforms designed to facilitate team

collaboration processes, such as planning, schedul-

ing, information lineage, brainstorming, data cre-

ation, gathering, and distribution (Gruba, 2004; Taras

et al., 2013; Gruba and Sondergaard, 2001). One

32

Obionwu, C., Karl, M., Broneske, D., Hawlitschek, A., Blockhaus, P. and Saake, G.

A Strategy for Structuring Teams Collaboration in University Course Projects.

DOI: 10.5220/0012075800003552

In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Smart Business Technologies (ICSBT 2023), pages 32-42

ISBN: 978-989-758-667-5; ISSN: 2184-772X

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

of such learning platforms is SQLValidator (Obionwu

et al., 2021; Obionwu et al., 2022). SQLValidator is

an integral part of the database courses held in our

faculty, and encompasses exercises, questionnaires,

and tests to assess students’ SQL programming skills.

Up till 2021 academic year, the platform was used

mainly as an individual learning platform, where col-

laboration between students was not possible. Due

to the increasing importance of teamwork, we inte-

grated the Teams component of the platform. Ergo

It’s description, and workflow, is an important topic in

this paper. Further important is the facilitation of task

reflection, and acquisition of collaborative problem-

solving skills. Our initial results show that, when stu-

dents collaborate, their solutions of project tasks are

on average better than those without visible collabora-

tion within a team. Furthermore, our investigation of

different degrees of instructional designs shows that

an explicit indication for team self-organization helps

in completing collaborative tasks more efficiently. In

summary, we contribute:

• a collaborative task design for SQL teaching

courses.

• an evaluation showing that collaboration leads to

better results when accomplishing SQL tasks.

This paper is structured as follows: in Section 2,

we discuss related work and, in Section 3, we describe

the design of our system. A characterization of partic-

ipating students of our study through a survey is given

in Section 4. An overview of the collaborative project

is given in Section 5, and team activity results are dis-

cussed in Section 6. In Section 7, we summarize and

indicate directions for future research.

2 RELATED WORK

Traditionally, teams are formed as a strategy for tack-

ling difficult challenges, or hard deadline scenarios.

A survey conducted in 2019 by Slack,

1

a highly pop-

ular collaboration platform revealed that ease of com-

munication resulted in good collaboration while top

collaboration challenges centered around communi-

cation difficulties as not being able to convey gestures.

In the subsequent paragraphs, we discuss the es-

sential features of freely available, or open-source

collaboration platforms that are used in the educa-

tional sector. To select these studies and platforms,

we did a literature search and the following platforms

have been selected:

1

https://slack.com/blog/collaboration/good-collaborati

on-bad-collaboration-a-new-report-by-slack last accessed

on 25.02.2022

Schom (Berj

´

on et al., 2015) is a tool for commu-

nication and collaborative learning, which employs

mobile instant messaging for the exchange of infor-

mation between members of an institution. It of-

fers interaction via e-mail, chat, discussion boards, or

microblogging and ensures digital anonymity. Thus,

users can anonymously interact with other users and

groups. Our Teams’ platform, unlike Schom, is de-

signed for effective interaction between students of a

team and, thus, each user knows its teammates as in

traditional scenarios.

Flipgrid (Edwards and Lane, 2021) is an online

video discussion tool that offers students a platform

to discuss ideas, communicate with their peers, and

practice their language and presentation skills. Its

popularity among educators is driven by the ease

by which it is set up and used in classes, and stu-

dents quickly engage in recorded online video-based

conversations with the teacher. It can also be ac-

cessed via internet browsers. Our Teams’ platform,

unlike Flipgrid, emphasizes textual communications

as using a text-based medium in computer-mediated

communication creates a more equitable and non-

threatening forum for discussions, especially those

involving women, minorities, and naturally reserved

personalities (Warschauer, 1997; Ferris and Hedg-

cock, 2013; Warschauer, 2004).

In UniConnect, lecturers create private course

communities and invite enrolled students. Each com-

munity offers dedicated blogs, wikis, forums, li-

braries, IBM docs, task management tools, and the

possibility of viewing group activity streams. Further-

more, students can create workgroups for their assign-

ments and projects. Our Teams’ platform does not

have this level of customization, which opens up fu-

ture work for us. While both systems allow students

to collaborate within and outside lecture periods, Uni-

Connect unlike Our Teams’ platform also features vir-

tual research teams that facilitate research coopera-

tion among two or more universities.

Remote Technical Assistance (RTA) (Blake,

2000), developed at UC Davis, is a collaborative tool

that features a chat system that facilitates random tex-

tual interactions via a TextPad window. It also al-

lows users to record and forward digitized sound and

create shared whiteboards using screen capture. The

chat program also lets each user remotely manipulate

his or her partner’s Web browser, and permits both

point-to-point and multipoint/group chat. The collab-

orative pedagogy of Our Teams’ platform is different

from that of RTA. Furthermore, Our Teams’ platform,

as we describe in Section 3, features a chat system,

code editor, task management system, and an instruc-

tor oversight feature that allows the integration of in-

A Strategy for Structuring Teams Collaboration in University Course Projects

33

Editor

Run / Run All

Clear query

Query

Show saved

list

Add query to

list

Statistics

Query Errors

Chats

Queries

Submissions

Group

Wiki

Queries

Task

Submission

Projects

Oversight

Chats

Instructor Access

Student Access

Teams

Admin

Groups

Project

Center

Project

groups

Semester

Tasks

Student Access

Instructor Access

Project

Reports

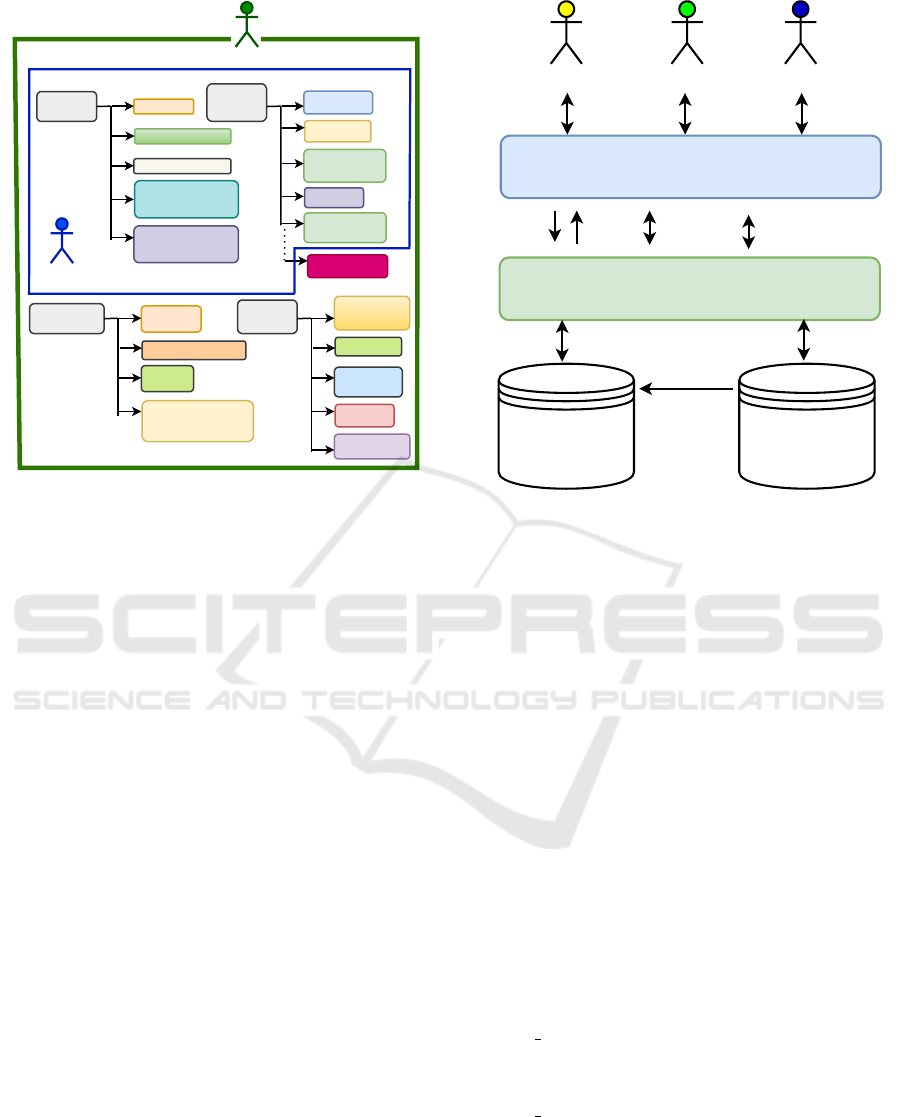

Figure 1: Teams Overview.

structional feedback.

Canvas is an open-source cloud-based learning

management platform (Desai et al., 2021; Mulder

and Henze, 2014), developed by the US infrastruc-

ture company. This platform consists of features, such

as page view count visualization, sentiment / mes-

sage classification and analysis. It has a hierarchical

assessment architecture that streamlines the deploy-

ment of courses and respective assessment modules.

Apart from being free for educators whose university

has no subscription, it also serves as a collaboration

platform. Our Teams’ platform does not have this

level of customization, which opens up future work

for us. While both systems allow students to collabo-

rate within and outside lecture periods, Canvas unlike

Our Teams’ platform is a full-fledged learning man-

agement system.

3 DESIGN AND

IMPLEMENTATION

Several systems have been developed to facilitate on-

line instructor / student interactions. One of such

web-based tools is SQLValidator (Obionwu et al.,

2021). The platform is an integral part of the database

courses held and encompasses exercises, question-

naires, and tests to assess students’ SQL program-

ming skills. Our Teams’ platform is the collaborative

environment for the platform. It is designed to facili-

tate high-level discussions, which are similar in qual-

PHP Server

Web Interface

instructorStudent Admin

Teams01 Sqlvali_data

fetch user

details

user

chat

user

query

error

user task

submission

team

interaction and

administration

data

organization

and task pool

data

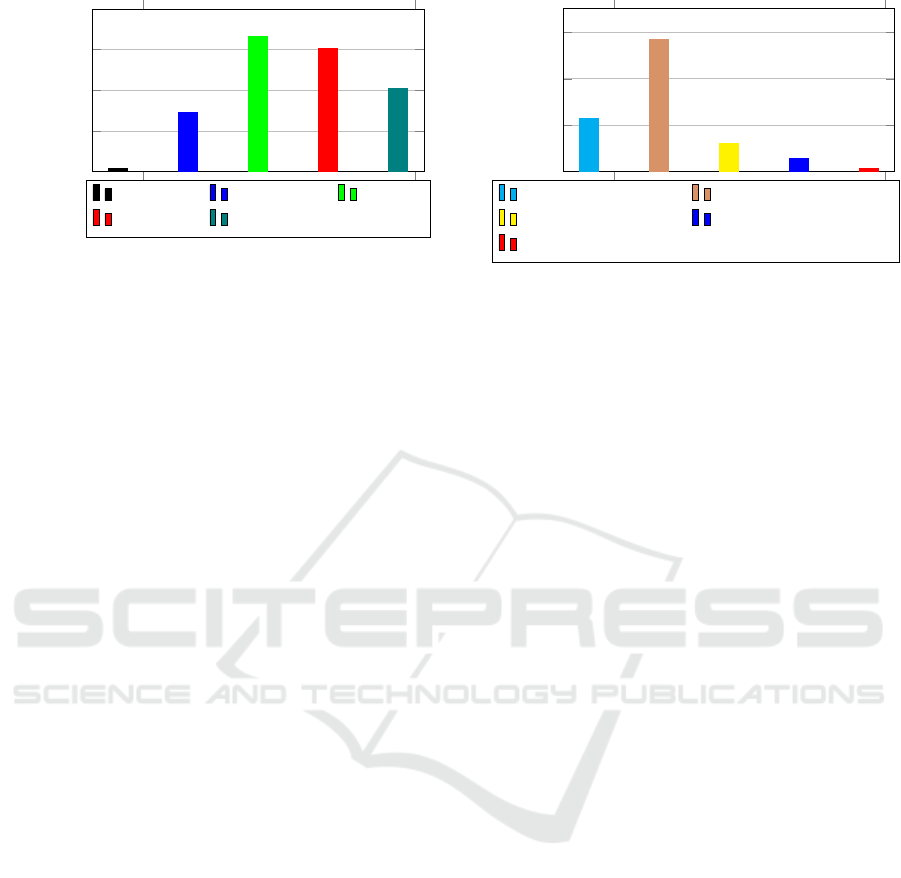

Figure 2: Teams Architecture.

ity to discussions that take place in traditional collab-

oration settings. Fig. 1 shows an overview of the sub-

system, differentiated by access.

3.1 Teams Architecture

There are three main features when implementing a

web-based application, these are centralization, repli-

cation, and distribution. The Teams’ system uses

a centralized client-server architecture. The general

architecture of the application has been depicted in

Fig: 2. As depicted, users interactions via a web in-

terface by way of posting chats, creating submissions

in the group wiki, and executing queries in the edi-

tor, etc. is mediated by a PHP server. The relational

database management system is tasked with storing

and managing all the data resulting from student, and

instructor interaction. To achieve this objective, the

Teams’ platform interacts with two main databases:

• db2 data contains all relevant data to maintain

the organization of the platform itself, such as user

management and task definitions.

• db1 teams01 contains all standard tables and data

used to support project task submissions, chat

management, user query evaluations, and admin

management.

Thus records of all user interaction is stored for ana-

lytical purposes.

ICSBT 2023 - 20th International Conference on Smart Business Technologies

34

Extract

Student's

Survey Input

Submit

Task ?

No

Yes

System

Mails

Instructor

Chat

students

Obtain

Access to

Teams

Create

& Update

Project

Reports

Instructor

Reviews

Submission

Save

Query

Create &

Update

Query

Instructor

Returns

Feedback

Partner

Recommendation

System

Release

next task

Has

Tasks been

Completed

?

Yes

No

Start

End

Instructional Feedback

Via

Oversight Access

Figure 3: Teams Workflow.

3.2 Student Access

As communication is often an integral feature of col-

laboration tools, we made the chat persistent in the

group-wiki, and code editor pages. Students have the

option of updating and deleting their chat posts. To

keep teams focused on current milestones, we struc-

tured the chat in pages. Only the latest 10 chat posts

are visible. History buttons are available to provide

access to previous chat posts. Our strategy aims to

instill a culture of self-assessment and reflection and,

thus, we allow teams to improve their solutions, and

resubmit again. This feature is accessible in the group

wiki/task submissions. Unlike the chat system, where

team members can edit and delete their chat posts,

team members can only create, read, update, but not

delete task submissions. Since many tasks are based

on the Structured Query Language SQL, our platform

includes a query editor. The editor, apart from ex-

ecuting queries, allows collaborators to store previ-

ously used queries. Thus, if in the course of the mile-

stones, it is required to alter the solutions, and hence

the queries, the team can access all their previous

queries from the group wiki. It also allows selected

execution of related queries. The group wiki gives

them access to the project tasks, saved queries, and

submission pages.

3.3 Instructor Access

The instructor, apart from having access to adminis-

trative activities, can grant itself membership of any

team where his feedback is required. This is facili-

tated via the oversight access shown in Fig. 3. Thus,

the instructor can perform CRUD operations on chats

posts, and task submissions. However, all the queries

executed in the instructor profile are not transferred

to the teams profile. In general, the oversight feature

facilitates the integration of instructional feedback,

which is typical for traditional team project interac-

tions. The teams overview diagram further (Fig. 1)

shows the other activities specific to administrators in

Our Teams’ platform.

3.4 Teams Workflow

Given that individual students have completed the

personality survey, team are generated via the part-

ner recommendation system, which is described in

obionwu et al. (Obionwu et al., 2023a). The ad-

ministrator loads several tasks into each team profile,

and initializes the teams. The student members gain

access, introduce themselves, and immediately start

interacting with the tasks in the group wiki. The inter-

action will result in chat, and project report commits,

and they agree that the answer to a respective ques-

tion, the project report is updated again, after which

a submission is made. Once the first task is solved

and submitted, the next task is activated. This process

continues until the last task is activated. Once a sub-

mission event is registered, the system mails the re-

spective instructor and the review process starts. Once

the review is done, the instructor, via the oversight

link, gives a response in the teams chat. Depending

on the response, the entry in the project report will

either be updated or left as the final response to the

respective question. This process will continue until

the final task. A description of the task is shown in

section 5.1

A Strategy for Structuring Teams Collaboration in University Course Projects

35

0

10

20

30

40

0.98

14.71

33.33

30.39

20.59

Fraction of Students

per Skill Level (%)

Excellent Very Good

Good

Fair

Poor

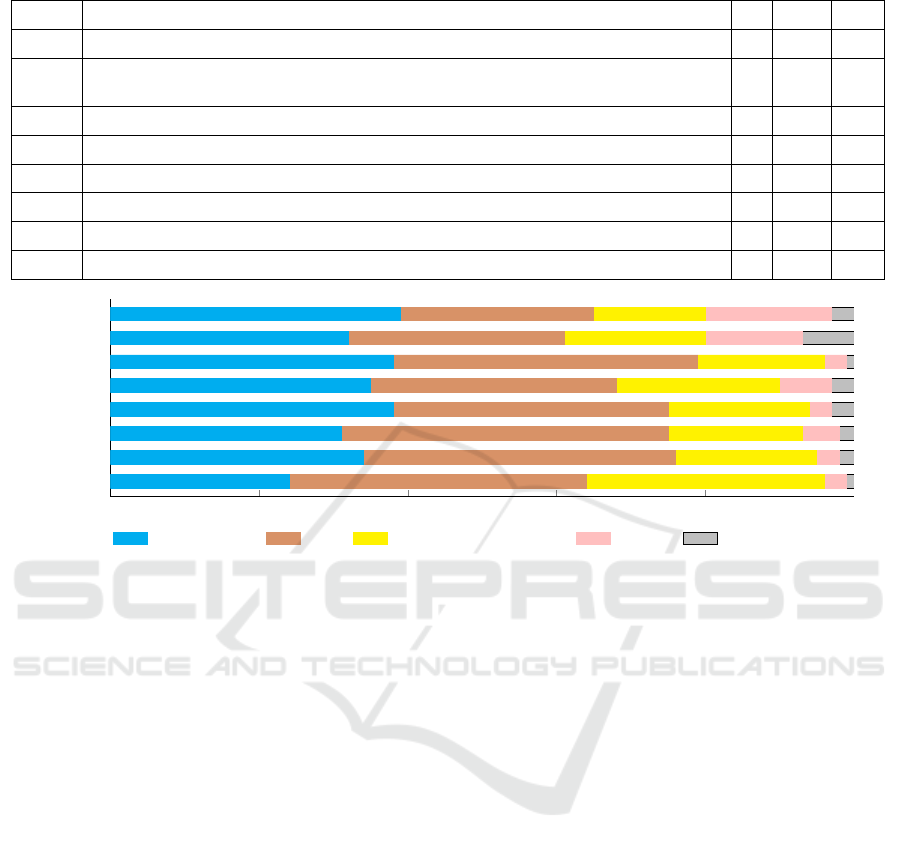

Figure 4: Student’s Initial Practical Programming Knowl-

edge.

4 SURVEY INSIGHTS

Being that the team projects were developed to stim-

ulate the cultivation of collaborative skills (Obionwu

et al., 2023b), having systems and structures gener-

ate collaborative behaviors alone is insufficient (Er-

bguth et al., 2022). Collaboration and team engage-

ment as a feature can be utilized to help learners co-

ordinate and communicate effectively to achieve a

common goal. Thus, to cultivate community learn-

ing and enhance collaboration, we designed tasks to

incorporate communication and not force them on

the students. We further sought to gain insight into

our student’s psychological affinity for collaborative

engagements, and behavioral dispositions to collab-

orative learning. To achieve these goals, we partly

adapted the ”Students’ Readiness for CSCL” ques-

tionnaire (Xiong et al., 2015). Eight items from this

questionnaire were selected from the ”Motivation for

collaborative learning” evaluation, and ten items were

selected from the ”Prospective behaviors for collab-

orative learning” questionnaire. In the 2023 winter

semester, we had 140+ enrollments in our teams’ plat-

form. Although we decided not to enforce survey

participation, 95 students from those enrolled in the

semester course participated in the surveys. Further-

more, we allowed the possibility of skipping sections

of the questionnaire. In the next subsection, we give

a description of the course participants based on the

survey results.

4.1 Participants

The pilot study was conducted in the context of

the 2021 database concept summer semester’s course

where students were required to form teams consist-

ing of 3 individuals as triads are typically more sta-

ble and engaging than other social network struc-

tures (Yoon et al., 2013), and well attuned to our

0

20

40

60

23.07

56.92

12.31

6.15

1.54

Experience with

group work (%)

Extremely familiar Moderately familiar

Somewhat familiar Slightly familiar

Not at all familiar

Figure 5: Student’s group work experience.

task structure as will be discussed in the next subsec-

tion. To increase trust among team members, team

formation took place at the beginning of the course.

But there were lots of teams breakdowns in the pi-

lot study. Thus, we developed a partner recommen-

dation system, which we currently employ to handle

team creation. The students completed personality

surveys, which allowed us to create the teams. These

new teams not only easily became acquaintance, but

showed willingness to deal with the team process. As

for the collaborative tasks, they are extracted from the

concepts described in the lectures, and theoretical ex-

ercises; thus, the teams are expected to have acquired

all the skills and information needed to engage with

the collaborative tasks.

Four exercise instructors oversaw the weekly ex-

ercise meetings and helped facilitate teamwork. To

estimate the participants perceptions and experiences

with respect to teamwork, and collaboration, we con-

ducted surveys. The result of our inquiry into their

self-perceived practical programming knowledge is

shown in Fig. 4. The results suggest that: about 1%

had extensive experience with general programming

15% were proficient, 33% had above-average expe-

rience, while 51% had rather limited programming

skills. Overall, a considerable number of the students’

population were beginners, and hence we taught them

the fundamentals of using SQL. Furthermore, Fig. 5

shows their team work experience. The results indi-

cate that: about 80% had worked in team projects or

tasks prior to enrolling in our course, while 20% had

limited team work experience and thus needed guid-

ance on how to work in team projects.

4.2 Collaboration and Team Interaction

Questioner Description

In the first survey among the participants of the

course, we aimed to elicit our participants’ self-

evaluation and experiences on team interaction, and

ICSBT 2023 - 20th International Conference on Smart Business Technologies

36

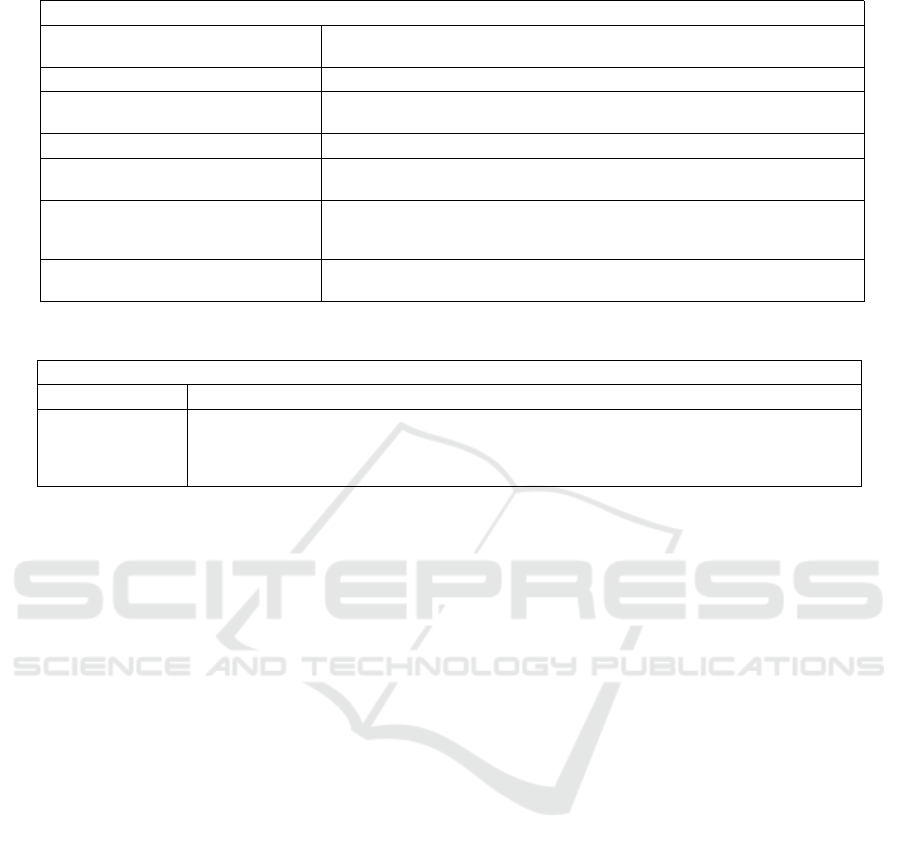

Table 1: Motivation for collaborative learning Questionnaire.

Item Motivation for collaborative learning No. Mean SD

Mot.1 I like to work with other students in group activities. 65 2.8 1.21

Mot.2

Comparing with doing individual assignments, it is more effective to learn by doing

group work.

65 2.85 1.21

Mot.3 I will need teamwork skills in my future job. 65 3.2 0.89

Mot.4 Working in groups allows me to tackle more complex topics than working individually. 65 3.05 1.08

Mot.5 There are many opportunities for discussion and sharing ideas by working in groups. 65 3.08 1.00

Mot.6 I believe I can do well in the group work. 65 3.15 0.87

Mot.7 I believe I can support group-mates. 65 3.2 0.90

Mot.8 I believe I can play an important role in the accomplishment of the group task. 65 3.02 0.89

0 20 40

60

80 100

Mot.1(%)

Mot.2(%)

Mot.3(%)

Mot.4(%)

Mot.5(%)

Mot.6(%)

Mot.7(%)

Mot.8(%)

3

7

1

3

3

2

2

1

17

13

3

7

3

5

3

3

15

19

17

22

19

18

19

32

26

29

41

33

37

44

42

40

39

32

38

35

38

31

34

24

%

Strongly Agree

Agree

Neither agree or disagree Disagree Strongly disagree

Figure 6: Motivation for collaborative learning feedback.

collaboration. A total of 65 of the participants re-

sponded to the optional voluntary survey at the begin-

ning of the course. Most of the users were between

the age of 27-31, and have previously not used our

collaboration platform.

We show descriptive statistics like the mean, the

standard deviation for the quantitative questions rated

on a 5-point Likert scale (in numeric representation: 0

= Strongly Disagree to 4 = Strongly Agree) in Table 1,

which contains questions and responses about their

motivation for teamwork, and in Table 2, we show

their self evaluation of their collaboration behavior.

The vast majority of quantitative replies were agree

(3) and Strongly Agree (4) on the scale. Therefore,

the standard deviations are fairly small for a vast ma-

jority of the questions. There were no questions that

were answered mostly negative, but there are several

questions with mixed replies. In general, questions

were prepared in such a way that not only percep-

tions about current team collaboration, and interac-

tion events are elicited, but also their previous col-

laboration and teamwork experiences, behavior, and

opinions.

We observe from Table 1 and the correspond-

ing plot, Fig. 6, that more than 65% of the partici-

pants liked working in groups (item Mot.1), and 61%

agreed that it was more effective to work in groups

(item Mot.2). 79% of participants in item Mot.3 held

a notion that teamwork skill was important for their

future job, while in item Mot.4, 68% agreed that

complex tasks can easily be tackled by sharing the

workload with group members. Furthermore, in item

Mot.5, 75% agreed that working in groups provided

opportunities for discussion and sharing of ideas, and

in item Mot.6, 75% can perform well while in group

work. 76% believed that they can support their group

mates in item Mot.7 and in item Mot.8, 64% believed

they can play an important role in the accomplishment

of the assigned group task.

Considering Table 2 and corresponding feedback,

Fig. 7, 60 students participated in this survey group

of question as our survey questions are not obliga-

tory, out of which 77% of the participants indicated

that they liked to share ideas (item Beh.1), and in

item Beh.2, 87% indicated that they were open to

new ideas. In item Beh.3, 84% are tolerant of dif-

ferent ideas. 82% indicated that they can express

their thoughts appropriately (item Beh.4) and 75%

further indicated in item Beh.5 that they always par-

ticipated appropriately during group work. In item

Beh.6, 73% of the participants indicated that they

were able to provide feedback on individual team

member’s performance, while 70% in item Beh.7 in-

dicated that they were able to provide feedback on in-

A Strategy for Structuring Teams Collaboration in University Course Projects

37

Table 2: Prospective behaviors for collaborative learning questionnaire.

Item Prospective behaviors for collaborative learning No. Mean SD

Beh.1 I like to share my ideas with others. 60 3.02 0.98

Beh.2 I am open to new ideas. 60 3.27 0.84

Beh.3 I am tolerant of different ideas. 60 3.25 0.88

Beh.4

I am able to express what I think in an appropriate way, not harming other group mem-

bers.

60 3.18 0.81

Beh.5 I always participate in an appropriate way. 60 3.13 0.83

Beh.6 I am able to provide feedback on overall team’s performance. 60 2.9 1.00

Beh.7 I am able to provide feedback on individual team member’s performance. 60 2.8 0.95

Beh.8 I am able to monitor my group’s progress. 60 2.87 0.98

Beh.9 I am able to implement an appropriate conflict resolution strategy. 60 2.77 0.95

Beh.10 I am able to recognize the source of conflict confronting my group. 60 2.87 1.02

0 20 40

60

80 100

Beh.1(%)

Beh.2(%)

Beh.3(%)

Beh.4(%)

Beh.5(%)

Beh.6(%)

Beh.7(%)

Beh.8(%)

Beh.9(%)

Beh.10(%)

3

2

3

2

2

3

3

2

3

2

5

5

8

7

6

17

15

13

15

23

20

22

20

28

23

42

37

37

42

35

48

48

42

40

38

35

47

47

40

40

25

22

28

23

30

%

Strongly Agree

Agree

Neither agree or disagree Disagree Strongly disagree

Figure 7: Prospective behaviors for collaborative learning feedback.

dividual team member’s performance as well as mon-

itor their group’s progress in item 8. Furthermore, in

item 9, 63% indicated that they were able to imple-

ment an appropriate conflict resolution strategy and

in item 10, 68% indicated that they were able to rec-

ognize the source of conflict confronting their group.

In general, the standard deviations from the mean

were modest, as most of the participants indicated

that they either agreed or strongly agreed with the

perceptions on collaboration and teamwork that were

queried about in the survey. So, in general, all par-

ticipants have a positive attitude and motivation to-

wards the expected teamwork. This is reinforced by

Fig. 5 which showed that about 80% of the partici-

pants already experienced group work. Thus, around

20% of our participants have not experienced work-

ing in teams. Ergo, our project was a guide for this

group of participants on the basics of teamwork, and

collaboration.

5 COLLABORATIVE PROJECT

STRUCTURE AND

PARTICIPANTS

5.1 Team Tasks

Our collaborative tasks are based on the Structured

Query Language SQL, a standard for performing

CRUD operations on a database. Thus, to create a

collaborative SQL project with reasonable level of

complexity, we employed the concept of roles. These

roles are known to affect how team members collab-

orate (Ruch et al., 2018), (Lyons, 1971), (Oke et al.,

2016), (Senior, 1997). Furthermore, regulating group

learning is important for learning processes and out-

comes.

Teams have to plan, monitor and evaluate, respec-

tively, reflect on their teamwork - a challenging task,

especially for novices in teamwork. A Collaboration

Script that guide the planning, monitoring, and re-

flection activities can support teams (N

¨

aykki et al.,

2017). Based on this, we created two conditions,

ICSBT 2023 - 20th International Conference on Smart Business Technologies

38

Table 3: Summary of our task description.

Collaborative Task Sections

Introduction and Objective

Motivates and stresses the importance of teamwork. Describes the expectancy of

each milestone.

Specification of Roles Explain the different roles to be assumed by participants of the team.

Teams, Role Formation, & Selection

Students form triad social units and choose either a stakeholder, an administra-

tor, or a developer role.

Planning and Task Sequence Explain the steps that teams should go through to achieve the objective.

Description of Tasks without reflection

script

A total of six tasks from database modeling to data definition and querying.

Description of tasks with reflection

script

In addition to the tasks with reflection script, it contains another first task, which

addresses project planning and an additional last task that inquires team reflec-

tion.

Reflection and Extension

Encourage teams with reflection script-based tasks to think about what has been

learned and how to apply that learning to different contexts.

Table 4: Sample tasks without reflection script.

Sample tasks without reflection script

Task Description

Task 1

ER modeling

The stakeholder(s) designs a use case for which the data management should be done. This use case

is described in a natural language formulation and an ER model is designed for it.

The created and described ER-diagram should contain at least 3 entities and two relations.

Please upload both in the project submission and discuss whether the solution needs adjustment.

structured, and unstructured projects, as we discuss

in Section 5.1.1. The general task description is de-

scribed in the next section.

Collaborative problem-solving facilitates not only

peer knowledge transfer but also several beneficial

skills, such as communication skills, teamwork, and

respect for others. It also stimulates independent re-

sponsibility for learning and sharing information with

teammates (Hung et al., 2008; Parker, 2006). Table 3

shows a summary of our task description. In general,

it is team-centered, and instructors do not dictate or

enforce any collaboration pattern. The overall scene

that we present in the part ”Introduction and Objec-

tive” is that students should follow the whole design

cycle within a data management project – from use

case modeling over schema design to schema defi-

nition and data analysis. To facilitate collaboration

within this scenario, we define the three roles: (1)

stakeholder, who is responsible for defining a com-

plex use case and interesting analyses, (2) adminis-

trator, who should create the schema and execute the

ETL process, and (3) the developer who implements

the analyses. To this end, students individually and

collaboratively assume responsibility for solving dif-

ferent aspects of the project milestones. The tasks

also encourage team strategy reflection. Thus, teams

have the option of re-evaluating, and resubmitting a

previously submitted solution. The goal here is to

induce learning strategies adjustment considerations

and stimulation of self-reflection skills.

5.1.1 Project Type

We created two project types, groups working on

tasks with reflection script and teams working on

tasks without reflection script groups, in order to as-

sess the impact of instructional guidance on the ex-

tent of collaboration. The tasks with reflection script,

shown in Table 4, had a general description of the

task, which was assigned to one of the roles (respon-

sibilities change from task to task). Furthermore, the

last instruction always asked for a critical discussion

inside the group.

In contrast to teams with reflection scripted tasks,

teams with tasks that require reflection, Table 5, were

required to plan their team work before the first task

submission. We further described the planning pro-

cess and possible discussion points. In the preceding

tasks, we also described steps to take and last steps

within their tasks required the teams to reflection on

what they have done. With these explicit instructions,

we aimed at encouraging students to collaborate and

especially to regulate their teamwork more systemat-

ically.

6 ANALYSIS OF THE

COLLABORATIVE PROJECT

Having described the platform, task groups, and their

respective tasks, we now provide a preliminary anal-

A Strategy for Structuring Teams Collaboration in University Course Projects

39

Table 5: Sample tasks with reflection script.

Sample tasks with reflection script

Task Description

Task 0

Project Planning

1. Meet online in the Teams Chat. Briefly discuss the task.

Are there any problems of understanding?

Clarify any questions about the task.

2. Then discuss the concrete implementation: make a time plan and distribute the roles (Considera-

tion: Do you already have experience with a certain role or do you want to strengthen your skills

in a certain role?) Please also store the role distribution.

3. Also, briefly discuss what you find important about teamwork.

What do you expect from your team members?

As a team, write down three key points that the team members want to adhere to.

Task 1

ER modeling

1. The stakeholder designs a use case for which the data management should be done. This use case

is described in a natural language formulation and an ER model is designed for it. The created

and described ER-diagram should contain at least 3 elements and two relations. Please upload

both in the project reports.

2. The two team members provide feedback on the stakeholder

´

s solution (assessment and sugges-

tions for improvement). Through this review process, all team members intensively deal with

each task.

3. Discuss (stakeholders) the feedback with the team members and discuss how to proceed.

Revise the original solution and upload the final result to project reports.

ysis of the collaborative activity. For this analysis, we

selected 28 teams from the 2023 winter semester. We

further used two indicators, the first of which is based

on the number of individuals that submitted respec-

tive tasks. Consequent on the user activity view fea-

ture in the teams’ environment, tutors can know who

solved the tasks. Thus, we differentiate between the

number of students submitting within the project team

as an indication for collaboration. Thus, the label ”3

submitters” (13 teams) implies that each of the team

members submitted at least one task, while ”2 submit-

ters” (8 teams) and ”1 submitter” (7 teams) implies

that only one or two team members did all the sub-

missions. Hence, many teams distributed the tasks

among themselves, which is a positive sign for the

overall collaborative setup. Still, when taking a more

in-depth look into the data, only 6 teams strictly fol-

lowed the role distribution. This is a common prob-

lem that also (N

¨

aykki et al., 2017) identified, as their

instructions were also often disobeyed. As a result,

we need to implement extra score credit incentives to

motivate collaboration among team members.

The second indicator is the project type (cf. Sec-

tion 5.1.1) as it should have an impact on the teams’

team work. In the charts, ”Str.” stands for groups

with tasks that require reflection, (13 groups) and ex-

plicit collaboration instructions, while ”Unst.” desig-

nates teams with tasks that required no reflection, (15

groups) with only recommendations for collaborative

practices. Notably, teams were shuffled in random

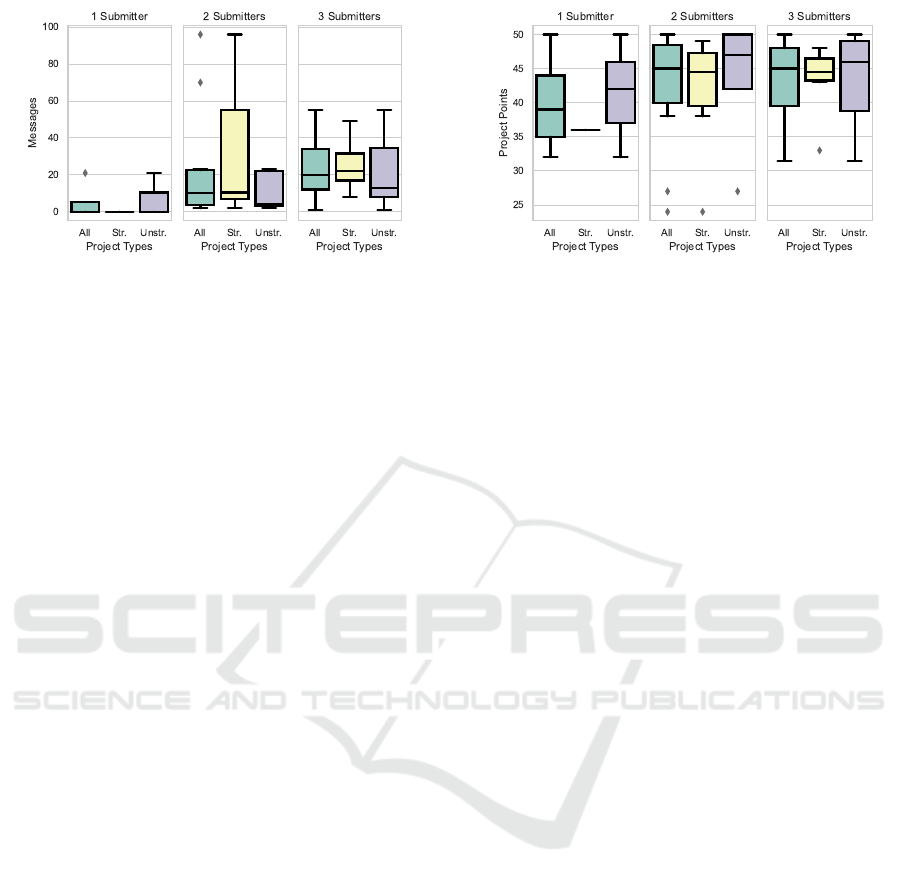

Figure 8: Scores in the Theoretical Exercise Submitted to

Moodle (thus, Moodle Points).

into one of both project types without them knowing

what task description they got.

In the following, we first analyze the skills and

motivation of the teams in forms of the Moodle sub-

mission, their messaging behavior, as well as their fi-

nal project grading.

6.1 Analysis of Team Skill and

Motivation

Fig. 8 shows the group scores obtained from the theo-

retical part of the exercises which preceded the team’s

project. These scores range from 61 (minimum crite-

rion for exam qualification) to 100 and usually rep-

resent the motivation of the students and their under-

standing of the exercises because these points come

ICSBT 2023 - 20th International Conference on Smart Business Technologies

40

Figure 9: Team Messages.

from graded team submission of theoretical exercise

tasks.

This analysis yields two insights. First, we can see

that student teams with a higher Moodle score (i.e.,

motivation) also tend to follow the rules of collabora-

tion more strictly, as we can see from the higher medi-

ans of Moodle points for the teams with two or three

submitters. Second, overall our random shuffling cre-

ated a small bias towards team tasks that required re-

flection where teams with tasks that required no re-

flection have, on average, better teams, which can in-

fluence the final points in the collaborative project.

6.2 Analysis of Chat Behavior

In Fig. 9, we show the messages sent through the in-

tegrated chat system. A positive result of this anal-

ysis is that when collaboration happens (i.e., two or

three people submitted tasks), teams working on tasks

with reflection requirement made more use of the in-

tegrated chats than teams working on tasks with no

reflection requirement. This is a positive sign that our

extra instructions for collaboration is fruitful. How-

ever, this result may also be as a consequence of the

extra score credit incentive they receive when instruc-

tors observe conversation in the team’s chat system.

Also, we observed that they used other social media

apps for communication, thus some of their real com-

munication may be hidden to us, and may follow a

different pattern.

6.3 Analysis of Project Results

At the end of the collaborative project, we graded the

submitted tasks of the teams. The maximum amount

of possible points is 50, with some teams having

achieved this, as visible in Fig. 10.

The score distribution leads to two insights. First,

comparing the median scores of all groups, teams

with more submitters also got better scores. Hence,

collaboration really helped students to reach better re-

Figure 10: Teams Project Scores.

sults in database-related tasks. Our second insight,

however, is that teams working on tasks with reflec-

tion requirement did not score as good as teams work-

ing on tasks with no reflection requirement, which is

against our initial goal. However, this could be ex-

plained by the results from Fig. 8, where teams work-

ing on tasks with no reflection requirement had more

Moodle points. This draws the conclusion that they

have better skill and motivation for the course, and

will, thus, lead to better results in the collaborative

project, and thus the acquisition and transfer of team-

work skills among team members.

7 SUMMARY AND FUTURE

DIRECTIONS

In this paper, we introduced Our Teams’ platform, a

web-based interactive collaborative learning platform

for learning and practicing SQL. We evaluated stu-

dents’ exercise engagements and presented their ac-

tivities and scores. In general, we observed that plac-

ing a collaborative task at the core of a class lec-

ture leads to students achieving better project results

and thus, an effective strategy that induces learning,

knowledge evaluation, and respective skill acquisi-

tion. Furthermore, our students were inclined to use

other social media apps for communication compared

to the internal chat system, and incentives as extra

score credit increased the likelihood that students will

comply to the rules of collaborative team engagement.

Our Teams’ platform is pedagogically structured to

stimulate reflection, a sense of community, and col-

laboration. In the future, we plan to explore how

student’s activity patterns can best be used to pro-

vide instructors and researchers with a clearer picture

of which course aspects students find most challeng-

ing. We also plan to extend the Teams system further

with collaboration stimulation, retrospective evalua-

tion, and graph learning features for better partner

A Strategy for Structuring Teams Collaboration in University Course Projects

41

selection recommendation and study engagement im-

provement.

REFERENCES

Berj

´

on, R., Beato, M. E., Mateos, M., and Fermoso, A. M.

(2015). Schom. a tool for communication and col-

laborative e-learning. Computers in Human Behavior,

51:1163–1171.

Blake, R. (2000). Computer mediated communication:

A window on l2 spanish interlanguage. Language

Learning & Technology, 4(1):111–125.

Desai, U., Ramasamy, V., and Kiper, J. (2021). Evaluation

of student collaboration on canvas lms using educa-

tional data mining techniques. In Proceedings of the

2021 ACM southeast conference, pages 55–62.

Edwards, C. R. and Lane, P. N. (2021). Facilitating student

interaction: The role of flipgrid in blended language

classrooms. Computer Assisted Language Learning

Electronic Journal, 22(2):26–39.

Erbguth, J., Sch

¨

orling, M., Birt, N., Bongers, S., Sulzberger,

P., and Morin, J.-H. (2022). Co-creating innovation

for sustainability. Gruppe. Interaktion. Organisation.

Zeitschrift f

¨

ur Angewandte Organisationspsychologie

(GIO), pages 1–15.

Ferris, D. R. and Hedgcock, J. (2013). Teaching L2 compo-

sition: Purpose, process, and practice. Routledge.

Gomez, E. A., Wu, D., and Passerini, K. (2010). Computer-

supported team-based learning: The impact of moti-

vation, enjoyment and team contributions on learning

outcomes. Computers & Education, 55(1):378–390.

Gruba, P. (2004). Designing tasks for online collaborative

language learning. Prospect, 19(2):72–81.

Gruba, P. and Sondergaard, H. (2001). A construc-

tivist approach to communication skills instruction

in computer science. Computer Science Education,

11(3):203–219.

Hung, W., Jonassen, D. H., et al. (2008). Problem-based

learning. Handbook of research on educational com-

munications and technology, 3(1):485–506.

Lyons, T. F. (1971). Role clarity, need for clarity, satisfac-

tion, tension, and withdrawal. Organizational behav-

ior and human performance, 6(1):99–110.

Michaelsen, L. K., Knight, A. B., and Fink, L. D. (2004).

Team-based learning: A transformative use of small

groups in college teaching.

Michaelsen, L. K. and Sweet, M. (2011). Team-based

learning. New directions for teaching and learning,

128(128):41–51.

Mulder, I. and Henze, L. (2014). Networked collaboration

canvas: How can service design facilitate networked

collaboration? In ServDes. 2014 Service Future; Pro-

ceedings of the fourth Service Design and Service In-

novation Conference; Lancaster University; United

Kingdom; 9-11 April 2014, number 099, pages 451–

453. Link

¨

oping University Electronic Press.

N

¨

aykki, P., Isoh

¨

at

¨

al

¨

a, J., J

¨

arvel

¨

a, S., P

¨

oys

¨

a-Tarhonen, J., and

H

¨

akkinen, P. (2017). Facilitating socio-cognitive and

socio-emotional monitoring in collaborative learning

with a regulation macro script–an exploratory study.

International Journal of Computer-Supported Collab-

orative Learning, 12(3):251–279.

Obionwu, C. V., Walia, D. S., Tiwari, T., Ghosh, T.,

Broneske, D., and Saake, G. (2023a). towards a strat-

egy for developing a project partner recommendation

system for university course projects. pages 144–151.

Obionwu, V., Broneske, D., et al. (2021). Sqlvalidator–an

online student playground to learn sql. Datenbank-

Spektrum, pages 1–9.

Obionwu, V., Broneske, D., and Saake, G. (2022). A collab-

orative learning environment using blogs in a learn-

ing management system. In Computer Science and

Education in Computer Science: 18th EAI Interna-

tional Conference, CSECS 2022, On-Site and Virtual

Event, June 24-27, 2022, Proceedings, pages 213–

232. Springer.

Obionwu, V., Broneske, D., and Saake, G. (2023b). Lever-

aging educational blogging to assess the impact of

collaboration on knowledge creation. International

Journal of Information and Education Technology,

13(5):785–791.

Oke, A., Olatunji, S., Awodele, A., Akinola, J., and Kuma-

Agbenyo, M. (2016). Importance of team roles com-

position to success of construction projects. Interna-

tional Journal of Construction Project Management,

8(2):141.

Parker, G. M. (2006). What makes a team effective or in-

effective. Organisational Development, Jossey-Bass

Reader, San Francisco, pages 656–680.

Ruch, W., Gander, F., Platt, T., and Hofmann, J. (2018).

Team roles: Their relationships to character strengths

and job satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychol-

ogy, 13(2):190–199.

Senior, B. (1997). Team roles and team performance: is

there ‘really’a link? Journal of occupational and or-

ganizational psychology, 70(3):241–258.

Sundstrom, E., De Meuse, K. P., and Futrell, D. (1990).

Work teams: Applications and effectiveness. Ameri-

can psychologist, 45(2):120.

Taras, V., Caprar, D. V., et al. (2013). A global class-

room? evaluating the effectiveness of global virtual

collaboration as a teaching tool in management educa-

tion. Academy of Management Learning & Education,

12(3):414–435.

Warschauer, M. (1997). Computer-mediated collaborative

learning: Theory and practice. The modern language

journal, 81(4):470–481.

Warschauer, M. (2004). Technology and social inclusion:

Rethinking the digital divide. MIT press.

Xiong, Y., So, H.-J., and Toh, Y. (2015). Assessing learners’

perceived readiness for computer-supported collabo-

rative learning (cscl): A study on initial development

and validation. Journal of Computing in Higher Edu-

cation, 27(3):215–239.

Yoon, J., Thye, S. R., and Lawler, E. J. (2013). Exchange

and cohesion in dyads and triads: A test of simmel’s

hypothesis. Social science research, 42(6):1457–

1466.

ICSBT 2023 - 20th International Conference on Smart Business Technologies

42