Bottlenecks in Regional Innovation Ecosystem: A Case on Region

with Extremely Low RDI Activity

Ville Pöntinen

a

and Jyri Vilko

b

Department of Industrial Engineering, Lappeenranta-Lahti University, Kauppalankatu 13, 45100 Kouvola, Finland

Keywords: Innovation Ecosystem, Regional Innovation Network, Knowledge Sharing, RDI.

Abstract: The benefits of innovation ecosystems and the knowledge they contain have long been studied as part of

business innovation and their importance has been recognized as vital for regional vigour. Ecosystems always

involve different kinds of actors and their mutual roles and dialogue form a complex system. This study

examined the performance of an innovation ecosystem in the region in southeast Finland through a single-

case study method. The region is known for the fact that very little innovation activity takes place within it.

The study used a group interview as the primary data collection method. The main findings indicated that

factors hindering RDI activities in the region include a lack of trust in the actors' relationships, which made

organizations less willing to collaborate, and a weak innovation culture, which appears to be caused in part

by the region's blue-collar traditions and low education levels. Furthermore, the innovation funding received

by local higher education institutions had not resulted in a significant increase in company RDI activity.

Another problem appeared to be that companies were not ready to commit to long-term co-development and

were more interested in achieving short-term benefits by focusing on ongoing projects.

1 INTRODUCTION

Research, development and innovation (RDI)

activities are widely acknowledged as pivotal drivers

of economic progress, catalyzing big leaps in

productivity by creating and implementing new

technologies and refined practices. At a concrete

level, effective RDI activities create, inter alia, new

employment opportunities, especially for people with

a higher education qualification, and enable a shift

towards the production of sophisticated, higher-value

products and services, which leads to economic

growth. This critical role of RDI is also reflected in

the European Union's collective target of allocating

3% of GDP to RDI investment. Increasing the amount

of RDI investments is especially integral for smaller

regions, ensuring their vitality in the long term and

establishing resilience to address wicked challenges.

In particular, the development of regional

innovativeness helps small regions that suffer from a

poor reputation and hence a lack of skilled labor

(Asheim & Coenen, 2005).

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0006-8475-6308

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9906-0470

A well-functioning innovation ecosystem fosters

cross-sector idea generation for new products and

combinations, while also cultivating an atmosphere of

trust among ecosystem participants, mitigating

uncertainty and aligning with prevailing perceptions,

values, and visions (Harmaakorpi & Melkas, 2005).

The convergence of diverse organizations and

communities within the ecosystem enriches both

explicit and tacit knowledge accessible to all

individuals (Schienstock & Hämäläinen, 2001, p.

144).

From a regional economic point of view, today's

innovation ecosystem functionality holds greater

significance than it did 30 years ago when mega

innovations were less frequent. Industrial regions can

no longer rely on a robust forest industry and paper

production as the production of both has declined

sharply in Finland during the 2000s (Metsäteollisuus,

2023). This shift, combined with growing

globalization, deregulation, and the emergence of

modern megatrends like the heavy usage of social

media and political instability has led us to the age of

temporary advantage, where sustainable advantage

174

Pöntinen, V. and Vilko, J.

Bottlenecks in Regional Innovation Ecosystem: A Case on Region with Extremely Low RDI Activity.

DOI: 10.5220/0012180900003598

In Proceedings of the 15th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2023) - Volume 3: KMIS, pages 174-184

ISBN: 978-989-758-671-2; ISSN: 2184-3228

Copyright © 2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

rarely if ever exists (D’aveni, Dagnino & Smith,

2010). Therefore, all regional actors must adapt to

these rapid changes and establish an ecosystem that

enables innovative operations in this dynamic

landscape, aiming to attain at least a temporary

advantage for a limited duration.

2 THEORETICAL

BACKGROUND

Ecosystem has rapidly become a buzz word in various

academic arenas. Innovation and regional

development are no exception in this regard, and

especially in the context of innovation, the ecosystem

paradigm has completely overtaken the traditional

systems discourse. Granstrand and Holgersson

(2020), for example, define an innovation ecosystem

as: “an evolving set of actors, activities, and artifacts,

and institutions and relations, including

complementary and substitute relations, that are

important for the innovative performance of an actor

or a population of actors.” The main objective for

these actors is to leverage the interdependencies to

create and capture shared value (Adner, 2017).

Regardless, the innovation ecosystem can be viewed

as a complex, evolving construct with a distinct

identity that resists replication across different

environments. It can be considered as a combination

of networks and systems (Durst & Poutanen,

2013). As such, innovation ecosystems appear to be

extremely diverse and heterogenic entities. Due to

this complex and heterogeneous nature, the weakness

of the concept is that there are many definitions of the

innovation ecosystem, and it is not possible to give a

completely unambiguous description (Oh, Phillips,

Park & Lee, 2016).

At a regional level, innovation ecosystems have

been studied for over 30 years. One of the first to

study regional innovation ecosystems was Scott

(1991), who analysed relations of economic systems

within regional innovation ecosystem in US. In

Europe, Fagerberg and Verspagen (1996) engaged in

comparable research, categorizing various types of

growth regions, each with distinct growth rates and

differing dynamics. Cooke et al. (1997) identified key

dimensions of a regional innovation system and tried

to make the concept more operational. More recent

regional ecosystem or network studies have focused

on knowledge flows and management (Harmaakorpi

& Melkas, 2005; Laihonen & Lönnqvist, 2015;

Radziwon et al., 2016), the role of regional

development officers (Sotarauta, 2010), value-

capture and creation process (Radziwon et al., 2016

and regional policy measures (Morgan, 2007).

Some have also researched the topic with a

systematic literature review approach. One literature

review was written by Durst and Poutanen in 2013,

who recognized multiple factors affecting the

innovation ecosystem performance: governance,

strategy and leadership, organizational culture,

human resource management, technology, partners,

and clustering.

This paper builds upon Durst's and Poutanen's

(2013) framework, enhancing it through the layered

classification of different levels in the ecosystem and

the incorporation of Chaudharry' et al., 2022 and van

der Panne, van Beers, and Kleinknecht's (2003)

literature reviews to this approach. Chaudharry et al.

(2022) specifically emphasize the open innovation

paradigm, thereby reinforcing the collaborative

aspects of Durst and Poutanen's (2013) innovation

ecosystem concept. Van der Panne et al.’s (2003)

study on the other hand offers a broader perspective

on factors promoting successful innovation.

The three papers have been combined to create a

collection of factors that evaluate ecosystem

performance at the individual, inter-firm, intra-firm

and ecosystem levels. Some of the factors from the

literature review by Durst and Poutanen (2013) have

been shifted to lower levels because they fit there

better. The following paragraphs and figure 1.

provide a summary of the factors drawn from these

three literature reviews affecting the performance of

the innovation ecosystem on different levels (Durst &

Poutanen, 2013; Chaudharry et al., 2022; Van der

Panne, 2003).

Within the innovation ecosystem, the wise use of

resources is crucial for economic development. Thus,

within the ecosystem, the ability of ecosystem actors

to manage (Watanabe & Fukunda. 2006) and allocate

(Tassey, 2010) resources efficiently across different

business operations is at the core of a well-

functioning system. However, this is not sufficient on

its own. The ecosystem must also have access to

different funding possibilities (Tassey, 2010; Samila

& Sorenson, 2010) such as through national or

international financial instruments that can be utilized

to boost the RDI activities in the ecosystem. Funding

should be directed toward all actors and their

activities, spanning organizational barriers (Durst &

Poutanen, 2013).

In evaluating the efficacy of ecosystem

operations, the role of governance must be

highlighted. Governance is a multifaceted construct

and therefore has several sub-categories affecting the

ecosystem functionality. For example, it should be

Bottlenecks in Regional Innovation Ecosystem: A Case on Region with Extremely Low RDI Activity

175

Figure 1: Factors affecting successful innovation (adapted from: (Durst & Poutanen, 2013; Chaudharry et al., 2022; Van der

Panne, 2003).

clear to all participating organisations what their role

is within the system (Tassey, 2010) and that there are

democratic Carayannis & Cambell, 2012) and data-

driven elements (Iyer & Davenport, 2008) included in

the decision-making process. These factors also help

in conducting timely decisions that make it possible

to act cohesively in the innovation process (Adner,

2006; Watanabe & Fukunda, 2006). For the

infrastructure to function effectively, it is important

that there is a continuous financial investment in the

ecosystem (Iyer & Davenport, 2008) and that systems

are flexible in a sense that they allow for smooth

interaction and expansion of the ecosystem whenever

necessary (Rohrbeck et al., 2009). Furthermore, well-

planned architectural control enables the goals and

objectives of partners to be aligned and systematic

risk assessment (Adner, 2006) helps mitigate

potential disruptions and setbacks in the ecosystem.

Strategy and leadership include subfactors that

affect day-to-day life in the ecosystem, particularly

when things do not go as planned. It is critical that the

ecosystem's actors have faith in their strategy and

remain patient (Iyer & Davenport, 2008) even when

things get tough. Hence, it is also important that the

leadership keeps the ecosystem's purpose clear to

participants, pays attention to detail (Iyer &

Davenport, 2008), and remembers to take at times a

distanced view to innovation (

Mezzourh & Nakara,

2012).

It is also essential for ecosystem that novel

information is brought into the ecosystem by different

people, especially researchers (Rohrbeck et al., 2009)

who are in touch with foreign research networks and,

thus, possess up-to-date knowledge from the

scientific fields. Moreover, a diverse array of

partnerships enhances the ecosystem's resilience.

While deeper partnerships are primarily established at

the inter-firm level, their impact resonates at the

ecosystem level, shaping collaborative dynamics and

diversity (Rohrbeck et al., 2009; Carayannis &

Campbell, 2012). One way to increase diversity is to

include university-industry collaboration in the

ecosystem (Mercan & Göktas, 2011).

While the ecosystem is a very abstract concept

and not limited to a particular cluster, there are still

benefits of such focus, particularly in terms of the

ease of interaction with other organisations and their

members when operating from the same physical

location (Mercan & Göktas, 2011). Technologies

(Carayannis & Campbell, 2012), on the other hand,

are the final factor that has an impact at the ecosystem

level. Their usefulness emerges, for example, through

the flexibility they bring to knowledge management

and the reduction in the need for human resources.

At the inter-firm level, interpersonal and

relationship factors include trust (Veugelers et al.,

2010; Rochford & Rudelius, 1997), commitment in

action (Rojas, 2018), and cultural differences (van de

Vrande et al., 2009). Knowledge leakages (Greco et

KMIS 2023 - 15th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

176

al., 2019) also fall into the same category. They can

be either intentional or accidental.

The effectiveness of cooperation at the inter-firm

level is also influenced by business and strategic

factor. This factor includes subfactors such as how

business models fit together (Brunswicker &

Chesbrough, 2018); Zhu, Xiao, Dong, & Gu (2019)

and how resources complement one another (Pullen

et al., 2012; Maidique & Zirger, 1984; Stuart &

Abetti, 1987) It is frequently the case that

complementary resources are required for productive

innovation activity. The companies' goals (Pullen et

al., 2012) should support each other properly in order

to guide the ecosystem in the appropriate direction at

the inter-firm level. However, sometimes the issue is

that certain organizations are more willing to take

risks whereas others are more risk-aversive

(Veugelers et al., 2010).

Legal factors and knowledge and information

management factors are two other sets of factors. The

first is primarily concerned with defining IPR rights

(Salge et al., 2013) in such a way that their absence

causes problems. In terms of knowledge

management, it is mainly a question about creating,

storing, and sharing knowledge optimally (

Rouyre &

Fernandez, 2019) and being able to transform

knowledge (Katila & Ahuja, 2002) in the proper

form.

At the intra-firm level, three main categories of

factors can be identified: knowledge and capabilities,

culture, and strategy and structure, the first of which

emphasizes matters like experience from previous co-

development activities with other organisations

(Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Maidique & Zirger, 1985;

Zirger, 1997). Similarly, intra-firm R&D capabilities

(Greco et al., 2019; Sofka & Grimpe, 2010) and

intensity (Kleinschmidt & Cooper, 1995; Stuart &

Abetti, 1987; Brouwer et al., 1999) are both important

and fundamental capabilities that enable smooth

collaboration with others in the creation of

innovation. Also strongly linked to these subfactors is

the organisation's ability to acquire and integrate

external knowledge smoothly for its own use

(Lichtenthaler, 2011; Salge et al., 2013)

When it comes to culture, the culture of the

organization (Ekvall & Ryhammar, 1998; Lester,

1998) is at the heart of everything the organization

does, and at its best, it enables smooth co-creation of

innovation. On the other hand, a culture of resistance

to change (Keupp & Gassmann, 2009) or the not-

invented-here (NIH) syndrome (Schaarschmidt &

Kilian, 2014), can be slowing factors. Similarly, the

commitment of the organisation's management

(Lester, 1998) has a major impact. If it does not show

real commitment to collaborative action, it is likely

that lower levels of the organisation will not do so

either. The strategy and structure on the other hand

focus on the company's strategy towards innovation

(Cottam et al., 2001) and whether the organization's

internal structure (Stuart & Abetti, 1987; Lester,

1998) promotes co-creation activities and is flexible

enough to make it possible.

Individuals have also an impact on the

ecosystem's ability to innovate. Factors include things

like knowledge and attitudes, and psychological and

cognitive abilities. The capacity to effectively apply

existing knowledge to advance an innovation

(Laursen & Salter, 2020) and attitudes toward

external knowledge and open innovation

(Lichtenthaler, 2011) are part of the first factor. The

latter, on the other hand, includes individuals'

emotional competencies and sense of self-efficacy

(McQuilken et al., 2018), and cognitive limitations

(Dahlander & Gann, 2010; Dahlander et al., 2016)

which both have an impact on the functionality of the

ecosystem.

3 RESEARCH DESIGN

This study centers on the region of Kymenlaakso in

Finland, which can be termed as an “extreme” due to

its heavy lack of RDI investments. There, RDI

investments amounted to only 0.5% of the region's

GDP in 2021 (Neittaanmäki, 2023) .This is the lowest

quotation of all Finnish regions. In the case of

Kymenlaakso, we can therefore speak of a real crisis

area, with serious problems in all areas of RDI

activity. Of particular concern, however, is the fact

that the level of business RDI investments in

Kymenlaakso has fallen by 14 percentage points

between 2017 and 2021 (Neittaanmäki, 2023). Thus,

Kymenlaakso not only starts from a disadvantage, but

it also faces the additional challenge of declining

regional innovation activity from its primary

innovation ecosystem actors - companies.

The study examined innovation ecosystem in

Kymenlaakso through a qualitative single case-study

method. A single case-study method was particularly

well suited for this paper, due to its capacity to

facilitate a synthesis and resolution of multiple cases

with the usage of diverse set of data sources.

Furthermore, it allowed the paper to address

important issues such as defining the essence of the

case and recognizing the knowledge that can be

obtained and learned from its in-depth analysis

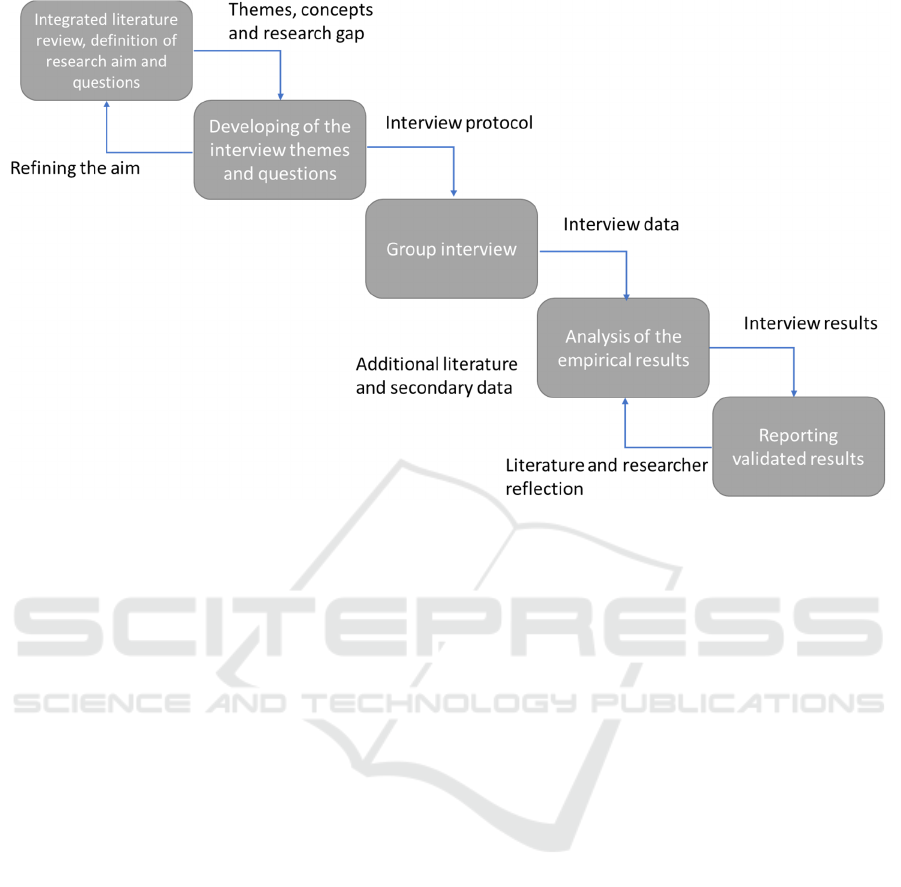

(Eriksson & Kovalainen, 2008). Figure 2. portrays in

more detail the process behind the methodology of

Bottlenecks in Regional Innovation Ecosystem: A Case on Region with Extremely Low RDI Activity

177

Figure 2: Development path of the study's methodology.

this study. Next, the stages of the research design for

this paper are further explained.

In practice, the first step was to conduct an

integrated literature review to support the definition

of the purpose of the study and the research question.

However, these were further refined afterwards, once

clear themes had been established and the final

interview questions and questions decided. The main

research question then became:

What factors hinder the functioning of the

innovation ecosystem in the region with extremely

low RDI activity and the emergence of new

innovations?

After determining the research question, the

interview protocol and data selection were defined. It

was decided that primary data would be gathered

through a group interview technique in which one of

the authors of this study served as a facilitator and led

the discussion using the interview questions shown in

Appendix 1. Thus, the interview technique could be

considered as a semi-structured interview in which

the facilitator asked open-ended questions from the

interviewee group, allowing the interviewees to

engage in a free dialogue on each topic.

Data selection followed an information-oriented

approach aimed at maximizing the informational

value from a limited sample size (Flyvbjerg, 2011).

The selected case subjects possess a high level of

expertise by default, given their pivotal roles within

the Kymenlaakso region's innovation ecosystem.

Consequently, they offer current insights into the

ecosystem's functioning, challenges, and trends. This

selection strategy is also particularly conducive to

gathering data on critical cases, which are cases of

significant magnitude that address well-known issues

(Flyvbjerg, 2011). Kymenlaakso serves as such a

critical case due to its limited innovation activity, and

this method can yield crucial insights and findings

that complement conventional perceptions of the

ecosystem's bottlenecks.

The interview took place via Teams, involving an

event facilitator and seven interviewees, whose

professional titles and organizations are detailed in

Table 1. This comprehensive interview, spanning

approximately 2 hours, covered predetermined topics

outlined in the interview protocol. Following the

interview, both authors reviewed and transcribed the

event recording. Subsequently, the authors engaged

in discussions to reach a consensus regarding the

bottlenecks identified by the interviewees.

Furthermore, the collected data was cross-referenced

with the findings from a study conducted by Finnish

Entrepreneurs, focusing on innovation network

activities across various Finnish regions. This study

was published during the finalization of this research.

Subsequently, the results from both primary and

secondary data sources were analysed, with

researchers reflecting on the interview transcriptions

and secondary data. Ultimately, all the analysed

primary and secondary data were compared with the

KMIS 2023 - 15th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

178

existing literature, and the authors synthesized their

findings.

Table 1: Interviewees information.

Interview subject’s job

title

Organisation

Chief executive officer Vocational institute

Competence development

manager

Project consultancy

company

School director

University of applied

sciences

Regional development

specialist

Regional council

Regional director

Project consultancy

company

Communication manager

Regional chamber of

commerce

Chief executive officer

Regional chamber of

commerce

Triangulation was used to increase the validity

and reliability of the study. Practically, it means that

several different data sources were used in the study

to develop an understanding of the complex

phenomenon. Firstly, the primary data gathering was

conducted as a group interview to collect the experts'

views on the situation in the region. On the other

hand, an external research paper that also addressed

the innovation ecosystem situation in the area was

utilized and compared with the experts’ views.

Finally, the study used it authors’ professional

knowledge consisting of innovation management on

the one hand and logistics, in particular supply chain

management, on the other. By combining this

knowledge with the literature and research data

collected, a high-quality reflection of the state of the

region's innovation ecosystem was achieved.

4 ANALYSIS

This section of the paper analyses the qualitative

group interview results about the networked RDI

activity in the region and addresses Finnish

Entrepreneurs’ (2023) barometer results at the end of

the chapter. During the interviews, several aspects

arose to highlight the poor network and culture in the

regional RDI that hinders the functioning of

innovation ecosystem. Overall, bottlenecks to

develop the culture of RDI were seen to hindering in

several aspects, especially in terms of inter-industrial

and university-company-level collaboration, in the

regional regulatory perspective, in personal and

organizational level trust. Especially the latter one

seemed to be a clear bottleneck in the larger RDI

actions which would require vast expertise from

different fields and thus difficult to manage by

individual organizations.

The lack of inter-firm and university-industry

level collaboration was restricted to customer

relationships in particular projects with strict focus on

certain outcome. The collaboration within the project

was typically active and it was seen fruitful between

the companies, however the collaboration was closed

by nature and limited to the short-term goals of the

project, and typically formally sealed with NDAs.

Overall, the companies did not practice collaboration

beyond formal contracts and especially collaboration

between organizations with different natures such as

university or university of applied sciences were seen

non-relevant. The more strategic perspective of the

possible competitive advantage between was not

identifiable for the companies and in many ways even

starting such collaboration seemed risky in the current

economic situation as a comment from a regional

project consultancy company revealed:

“Anything else than our own RDI activity is

foreign to us. We don’t see it as a part of our

operations. Our role in the projects is rather to be a

stooge and we don’t consider ourselves as such a

strong actor which would consider wider and long-

term RDI activity to be natural”

Apart from the challenges in industry

collaboration, significant gaps existed between the

two universities in the region. The university of

applied sciences had a long-standing presence in the

region and played a substantial role in securing

regional development funding. In contrast, the

university unit in the region had been a much smaller

entity, with only a few researchers based there.

However, the university had expanded its presence in

a neighbouring region through mergers with two

universities of applied sciences. In the past, there had

been discussions about a potential merger with the

regional university of applied sciences, but this idea

had been met with resistance. While collaboration

between these two institutions functioned at some

levels, significant difficulties arose at the upper

management level. The university of applied sciences

did not view strategic collaboration as relevant and,

instead, regarded the university as a competitor,

especially because the university had become more

active in the region lately. The problematic

relationship between these two was also seen in the

interview, from the comments of the university of

applied sciences that were directed to undermine the

university’s collaboration with the companies:

Bottlenecks in Regional Innovation Ecosystem: A Case on Region with Extremely Low RDI Activity

179

“In the university, they are focusing just on

writing academic papers”

This was referring to the fact that one of the

university’s main functions was to produce scientific

publications, and the companies would not benefit

from the collaboration. This was one of the examples

which indicated the lack of trust in the RDI network.

Similarly, the lack of trust was seen to be relevant

among the companies and universities as well, as one

of the comments from the companies revealed:

“We would like to see examples of projects on

how our confidential data is being used, and how the

collaboration with companies is handled”

The utilization of public funding was lacking in

the region. While the region was considered low

developed and thus received relatively high regional

development support, it was underutilized by the

companies. While the university of applied science

had a strong project funding portfolio, in fact the

largest in the country compared to other universities

of applied sciences, alone it did not seem to make

enough impact to the culture. From the companies

perspective the regional RDI funds were not seen that

relevant to their functions and especially the reports

were seen as cumbersome:

“We are bad in utilizing public funding as it

entails reporting. Economic cycles also have an

effect. When the economy is booming, we are too busy

and when its falling, we don’t have enough money for

RDI”The structure of the regional industry was one

of the most mentioned problems in the region. The

old brick-and-mortar heritage, where there had been

always someone who told managers what to do and

how had sticked into culture. The once-vital pulp and

paper giants, which had long served as the backbone

of local businesses, were now in decline, with

factories shutting down and their local RDI functions

relocated to other regions. Some optimism emerged

from the prospects of green transformation, along

with the potential investments in hydrogen and

battery industries slated for the region. However,

these new industries encountered regulatory

challenges at the regional level, with lengthy

complaints lodged against their projects. Overall, the

local attitude towards RDI was seen difficult:

“The local opinion and culture for RDI activities

is not easy. We’ve experienced often rounds of

complaints against development projects”

The regional RDI-activities had risen as a concern

for different players in the region in the previous

years, as one of the recent activities a college

association was founded to fund professorships and to

strengthen the RDI activities in the region. The

association had also collected funds to establish

renewable energy and cyber security professorships

in the region to help in the local RDI. The chamber of

commerce and the regional council had noticed a gap

in knowledge of how academic research is done in the

region and ordered a consult to investigate this. In

addition to the association, the local chamber of

commerce had recently activated to facilitate the

collaboration and discussion around RDI.

While there was a severe bottleneck in the

regional RDI network, a recent study by Finnish

Entrepreneurs (2023) revealed the strength of the

inter-organizational collaboration between the

companies. In the study, the region was ranked as the

best in Finland. Therefore, it can be argued, that while

the wider RDI collaboration is lacking, companies are

focusing on direct contract-based relationship

management.

5 CONCLUDING DISCUSSION

RDI activities are the essence of long-term

competitiveness for companies, and thus one of the

keys to regional development as well. While Finland

is considered one of the most innovative countries in

the world, and the Research and Innovation Council

of Finland has set up a vision for Finland to become

the most attractive and competent environment for

experimentation and innovation by 2030, there are

major regional differences within the country

(Rinkkala et al. 2019; The Research and Innovation

Council, 2017). This research focused on one of the

lowest RDI-funding receiving regions in Finland to

study the bottlenecks for ecosystem and networked

innovation activities. The study revealed that there

are several factors contributing to the lack of

innovation activity in the region, especially the lack

of networked innovation seemed to suffer in the

region.

As one of the most important factors, the lack of

trust in the ecosystem, inter-firm, and individual

levels seemed to hinder the collaboration activities

between the companies. This relates to the literature,

as several other studies have also identified trust and

its lack as a problem that hinders cooperation among

actors that participate in RDI activities (Veugelers et

al., 2010); Rochford & Rudelius, 1997). The lack of

trust was relevant to the company-university

collaboration as well.

The organizations interviewed were suspicious

about the confidential information being delivered to

the universities and in some ways did not understand

what kind of benefits there could be in the

collaboration, likely because of a lack of prior

KMIS 2023 - 15th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

180

knowledge and experience with the university

cooperation. Other research literature recognizes that

sharing information and building trust takes time and

does not happen instantaneously (Schartinger et al.

2001; Nsanzumuhire & Groot, 2020). Similar

indications can be seen in this study as the university

in Kymenlaakso is only now beginning to take a

greater role in regional development. On the other

hand, the research field has also found that clear and

wide contractual agreements regarding knowledge

sharing can improve trust in university-industry

collaboration (Hemmert et al., 2014), which could

also be a way to ease the collaboration in this case

where no long-term relationships are established yet.

While public RDI funding was available for the

companies, they considered the reporting required by

the funding to be excess work and therefore did not

apply it. In other studies (Tassey, 2010; Samila &

Sorenson, 2010), additional funding was found to

have a positive effect on innovation activity in the

ecosystem level, but in this research, the effect was

more neutral, as even if funding was available, firms

did not possess resources or skills to apply for it due

to the time limits and effort required, showing that the

lack of experience and capabilities prevented

effective action. This is in line with (Sanchez-Vidal

& Martin-Ugedo, 2005) finding that firms, especially

SMEs lack of knowledge on how to approach

different sources of funding prevents them from

gaining more funding.

In addition, the poor innovation culture related to

the old industrial traditions in the region opposed

challenges for the proactive thinking and mindset of

the people. The region's innovativeness suffers from

the reasonably low education of the people and the

working population comprises mostly from blue-

collar workers. The old industrial plants have been

closing in the region and shifted their RDI functions

to other regions. Similarly, the region has one of the

lowest in-house investors lists as well. The companies

in the region typically focus on closed customer-

related dyadic RDI projects and were struggling to

see the benefit of developing their competencies

through ecosystemic collaboration with other

organizations or institutions.

The role of the university in the region is still

limited due to the fact that there is no established

university campus in the region, rather smaller

research units, with scarce resources. The role of the

university of applied sciences has been however

larger in the region and in many ways, and it has been

responsible for the RDI activities. Indeed, the funding

received by the local university of applied science is

the highest in the country (XAMK, 2019). As the

main actor the university of applied science however

does not seem to be sufficient to lift the RDI activity

in the region. Moreover, the funding received by the

university of applied sciences did not seem to help the

local companies and their RDI activities or increase

funding. A somewhat similar case can be found in the

city of Twente, which, like the Kymenlaakso region,

has a long history as an industrial area. In Twente, the

local university has been able to create some level of

transformation in the innovative capacity of the

region (Hospers & Benneworth, 2012). Nevertheless,

this study shows that always local university actors

cannot translate the abundant RDI funding into

increased regional innovation capacity.

The role of different actors in the networked RDI

activities is relevant especially when trying to

develop the culture of innovation. Some regional

actors had been introduced in order to boost the RDI

activities, however the overall collaboration was still

in its infancy. The regional council had introduced

smart specialization fields according to which the

strategic RDI funding were allocated, however a clear

roadmap about the collaborative arrangements

toward these were lacking. With clear lack of trust

among members and some of the actors still seeking

their place in the ecosystem, the maturity of the

overall RDI ecosystem was still in its infancy

This text has several scientific and managerial

implications: Firstly, the paper sheds light on the

networked innovation activities at a local level by

assessing different aspects of the innovation

indicators. In doing this especially the bottlenecks of

the current case illustrate how the long-term strategic

collaboration with different types of organizations

and institutes suffers as the companies only focus on

short-term benefits in the ongoing projects and also

while showing how the lack of trust and the fear that

sharing information is more bad than good

contributes to business fragmentation and hinders

ecosystem innovation(Tassey, 2010; Rojas et al.,

2018). Secondly, the study provides information

about an extreme case of a low innovation activity

region and how historical weight and resistance to

change can be hindering the development of

innovation culture and activities (Keupp &

Gassmann, 2009; Schaarschmidt & Kilian, 2014).

Finally, the paper illustrates how limited

understanding of different organizations roles and

activities can be a bottleneck for the regional

innovations (Tassey, 2010).

In the future, more research should be focused on

the network types and roles of different organizations,

and how homogenous the ecosystem is. Some

researchers have already started this work (Sotarauta,

Bottlenecks in Regional Innovation Ecosystem: A Case on Region with Extremely Low RDI Activity

181

2010; Laihonen & Lönnqvist, 2015; Radziwon et al.,

2016). More research is also needed on innovation

culture change management. It would benefit similar

types of regions, networks and organizations in them.

In addition, more knowledge is required on how to

transform an industrial region into a more innovative

one and how the university or university of applied

science can play an effective role in enabling this via

ecosystemic development.

Organizations and managers should acquire more

knowledge on how wider and long-term innovation

projects are managed and what kind of benefits could

be expected from participating actively in innovation

ecosystems. Moreover, distrust (Westergren, 2011)

and competitive positions between different

organizations and institutions can be harmful to

organizations, and in order to develop an innovation

culture management support is essential (Lester,

1998). On the other hand, active regional actors must

make every effort to lower the barriers to attending

innovation ecosystem and thus enable trust to develop

between the actors in the region (Hemmert et al.,

2014; Nsanzumuhire & Groot, 2020).

Finally, as a source of competitiveness and

growth, managing and developing the regional

innovation ecosystems is essential. Currently, new

technologies and many other changes and trends are

increasing the necessity for companies to develop

their operations and value production accordingly.

With low innovation areas, the changes are more

difficult to implement and without changes, the

organization's competitiveness will most likely fall

and with that the regional one falls as well.

REFERENCES

Adner, R. (2017). Ecosystem as Structure: An Actionable

Construct for Strategy. In Journal of Management

43(1), 39–58.

Adner, R. (2006) Match Your Innovation Strategy to Your

Innovation Ecosystem. In Harward Business Review,

84(4), 98-107.

Asheim, B. & Coenen, L. (2005). Knowledge Bases and

Regional Innovation Systems: Comparing Nordic

Clusters. In Research Policy, 34, 1173-1190.

Brouwer, E., Budil-Nadvornikova, H. & Kleinknecht, A.

(1999). Are urban agglomerations a better breeding

place for product innovation? An analysis of new

product announcements. In Regional Studies, 33(6),

541–549

Brunswicker, S., & Chesbrough, H. (2018). The adoption

of open innovation in large firms: Practices, measures,

and risks—A survey of large firms examines how firms

approach open innovation strategically and manage

knowledge flows at the project level. In Research

Technology Management, 61(1), 35–45.

Carayannis, E. G. & Campbell, D. F. J.(2012). Mode 3 and

Quadruple Helix: toward a 21st century fractal

innovation ecosystem. In International Journal of

Technology Management, 46(3-4), 201-234.

Chaudhary, S., Kaur, P., Talwar, S., Islam, N., & Dhir, A.

(2022). Way off the mark? Open innovation failures:

Decoding what really matters to chart the future course

of action. In Journal of Business Research, 142, 1010-

1025.

Cohen, W. M., & Levinthal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive

capacity: A new perspective on learning and

innovation. In Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1),

128–152.

Cooke, P,. Uranga, M,. & Etxebarria, G. (1997). Regional

Innovation Systems: Institutional and Organisational

Dimensions. In Research Policy, 26, 475-491.

Cottam, A., Ensor, J. & Band, C. (2001) A benchmark study

of strategic commitment to innovation. In European

Journal of Innovation Management, 4, 88–94

Durst, S. & Poutanen, P. (2013). Success factors of

innovation ecosystems-Initial insights from a literature

review. In CO-CREATE 2013: The Boundary-Crossing

Conference on Co-Design in Innovation, Aalto

University, 27-38.

Dahlander, L., & Gann, D. M. (2010). How open is

innovation? In Research Policy, 39(6), 699–709.

Dahlander, L., O’Mahony, S., & Gann, D. M. (2016). One

foot in, one foot out: How does individuals’ external

search breadth affect innovation outcomes? In Strategic

Management Journal, 37(2), 280–302.

D'Aveni, R.A., Dagnino, G.B. and Smith, K.G. (2010), The

age of temporary advantage. In Strategic Management

Journal,31(13),1371-1385.

Ekvall, G. & Ryhammar, L. (1998). Leadership style, social

climate and organizational outcomes: A study of a

Swedish University Colleges. In Creativity and

Innovation Management, 7(3), 126–130

Eriksson, P. & Kovalainen, A. (2008). Introducing

Qualitative Methods: Qualitative methods in business

research. London, SAGE Publications.

Fagerberg, J. & Verspage, B. (1996). Heading for

Divergence? Regional Growth in Europe Reconsidered.

In Journal of common market studies, 34(3), 431-448.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2011). Case Study, in Norman K. Denzin and

Yvonna S. Lincoln, eds., In The Sage Handbook of

Qualitative Research, 4th Edition (Thousand Oaks,

CA: Sage, 2011),17, 301-316.

Granstrand, O. & Holgersson, M. (2020). Innovation

ecosystems: A conceptual review and a new definition.

In Technovation, 90-91.

Greco, M., Grimaldi, M., & Cricelli, L. (2019). Benefits and

costs of open innovation: The BeCO framework. In

Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 31(1),

53–66.

Han, C., Thomas, S., Yang, M., & Cui, Y. (2019). The ups

and downs of open innovation efficiency: The case of

Procter & Gamble. In European Journal of Innovation

Management, 22(5), 747–764.

KMIS 2023 - 15th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

182

Harmaakorpi, V. and Melkas, H. (2005). Knowledge

management in regional innovation networks: the case

of Lahti, Finland. In European Planning Studies, 13(5),

641-659.

Hemmert, M., Bstieler, L., & Okamuro, H. (2014).

Bridging the cultural divide: Trust formation in

university–industry research collaborations in the US,

Japan, and South Korea. Technovation, 34(10), 605–

616.

Hospers, J-A. & Benneworth, P. (2012) Innovation in an

old industrial region: the case of Twente. International

Journal of Learning and Intellectual Capital, 9(1/2), 6-

21.

Iyer, B. & Davenport, T. H. (2008). Reverse engineering:

Google’s innovation machine. In Harvard Business

Review, 86(4).

Laihonen, H. & Lönnqvist, A. (2013). Managing regional

development: A knowledge perspective. In Intenational

Journal of Knowledge-Based Development, 4, 50-63.

Laursen, K., & Salter, A. (2020). Who captures value from

open innovation—the firm or its employees? In

Strategic Management Review, 21(1), 1–9.

Lester, D.H. (1998). Critical success factors for new

product development. Research Technology

Management, 41(1), 36–43

Lichtenthaler, U. (2011). Open innovation: Past research,

current debates, and future directions. In Academy of

Management, 25(1), 75–93.

Katila, R., & Ahuja, G. (2002). Something old, something

new: A longitudinal study of search behavior and new

product introduction. Academy of Management

Journal, 45 (6), 1183–1194.

Keupp, M. M., & Gassmann, O. (2009). Determinants and

archetype users of open innovation. In R&D

Management, 39(4), 331–341.

Kleinschmidt, E.J. & Cooper, R.G. (1995) The relative

importance of new product success determinants:

Perception versus reality. In R&D Management, 25(3),

281–297.

Maidique, M.A. & Zirger, B.J. (1985) The new product

learning cycle. In Research policy, 14, 299–313

McQuilken, L., Robertson, N., Abbas, G., & Polonsky, M.

(2018). Frontline health professionals ’ perceptions of

their adaptive competences in service recovery. In

Journal of Strategic Marketing, 1, 70-94.

Mercan, B. & Göktaş, D. (2011). Components of

Innovation Ecosystems: A Cross-Country Study. In

International Research Journal of Finance and

Economics, 76, 102–112.

Metsäteollisuus. (2023). Forest industry production

volumes since 1960. available at:

https://www.metsateollisuus.fi/newsroom/forest-

industry-production-volumes-since-1960

Mezzourh, S. & Nakara, W. A. (2012). New Business

Ecosystems and Innovation Strategic Choices in SMEs.

In The Business Review, 20(2), 176-182.

Morgan, K. (2007). The Learning Region: Institutions,

Innovation and Regional Renewal. In Regional Studies,

41.

Neittaanmäki, P. (2023). Tutkimus- ja kehittämismenot

sekä bruttokansantuote maakunnittain vuosina 2017-

2021. In Informaatioteknologian tiedekunnan

julkaisuja 97. Jyväskylän yliopisto, Informaatio

teknologian tiedekunta.

Nsanzumuhire, S. & Groot, W. (2020). Context perspective

on University-Industry Collaboration processes: A

systematic review of literature. Journal of Cleaner

Production, 258, 120861.

Oh, D-S, Phillips, F., Park, S. & Lee, E. (2016). Innovation

ecosystems: A critical examination. In Technovation,

54, 1-6.

Pullen, A. J. J., De Weerd-nederhof, P. C., Groen, A. J., &

Fisscher, O. A. M. (2012). Open innovation in practice:

Goal complementarity and closed NPD networks to

explain differences in innovation performance for

SMEs in the medical devices sector. In Journal of

Product Innovation Management, 29(6), 917–934.

Radziwon, A., Bogers, M & Bilberg, Arne. (2016).

Creating and Capturing Value in a Regional Innovation

Ecosystem: A Study of How Manufacturing SMEs

Develop Collaborative Solutions. In International

Journal of Technology Management, 75.

Rinkkala, M., Lauonen, P., Weckström N., & Koponen, P.

(2019). Internationally significant innovation and

growth ecosystems in Finland. Spinverse Oy. Available

at: https://teknologiateollisuus.fi/sites/default/files/

2020-01/Internationally%20significant%20innovation

%20and%20growth%20ecosystems%20in%20Finland

.pdf

Rochford, L. & Rudelius, W. (1997.) New product

development process; stages and successes. In

Marketing Management, 26, 67–84

Rohrbeck, R., Hölze, K. & Gemünden, H. G. (2009).

Opening up for competitive advantage – How Deutsche

Telekom creates an open innovation ecosystem. In

R&D Management, 39(4), 420–430.

Rojas, B. H., Liu, L., Lu, D., Rojas, B. H., Liu, L., & Lu, D.

(2018). Moderated effect of value co-creation on

project performance. In International Journal of

Managing Projects in Business, 11(4), 854–872.

Rouyre, A., & Fernandez, A. S. (2019). Managing

knowledge sharing-protecting tensions in coupled

innovation projects among several competitors. In

California Management Review, 62(1), 95–120.

Salge, T. O., Farchi, T., Barrett, M. I., & Dopson, S. (2013).

When does search openness really matter? A

contingency study of health-care innovation projects. In

Journal of Product Innovation Management, 30(4),

659–676.

Samila, S. & Sorenson, O. (2010). Venture capital as a

catalyst to commercialization. In Research Policy,

39(10), 1348-1360.

Sánchez-Vidal, J & Martín-Ugedo, J. F. (2005). Financing

Preferences of Spanish Firms: Evidence on the Pecking

Order Theory. In Review of Quantitative Finance and

Accounting, 25(4), 341–355.

Schaarschmidt, M., & Kilian, T. (2014). Impediments to

customer integration into the innovation process: A

Bottlenecks in Regional Innovation Ecosystem: A Case on Region with Extremely Low RDI Activity

183

case study in the telecommunications industry. In

European Management Journal, 32(2), 350–361.

Schartinger, Schibany, A., & Gassler, H. (2001). Interactive

Relations Between Universities and Firms: Empirical

Evidence for Austria. In The Journal of Technology

Transfer, 26(3), 255–255.

Schienstock, G. & Hämäläinen, T. (2001) Transformation

of the Finnish Innovation System: A Network Approach,

Reports Series, 7. Helsinki. Sitra.

Scott, A. (1991). The aerospace-electronics industrial

complex of Southern California: The formative years,

1940–1960. In Research Policy, 20(5), 439-456.

Sofka, W., & Grimpe, C. (2010). Specialised search and

innovation performance—Evidence across Europe. In

R&D Management, 40(3), 310–323.

Sotarauta, M. (2010). Regional Development and Regional

Networks: The Role of Regional

Development Officers in Finland. In European Urban and

Regional Studies, 17(4), 387-400.

Stuart, R. & Abetti, P.A. (1987) Start-up ventures: Towards

the prediction of initial success. In Journal of Business

Venturing, 2, 215–230.

Finnish Entrepreneurs. (2023). Elinvoimabarometri.

Available at: https://survey.taloustutkimus.fi/

dashboard/elinvoimabarometri/index-en.html

Tassey, G. (2010). Rationales and mechanisms for

revitalizing US manufacturing R&D strategies. In

Journal of Technological Transformation, 35, 283–

333.

The research and innovation council of Finland. (2017).

Vision and road map of the Research and Innovation

Council Finland. Available at: https://

valtioneuvosto.fi/documents/10184/4102579/Vision_a

nd_roadmap_RIC.pdf/195ec1c2-6ff8-4027-9d16-d561

dba33450

van der Panne, G., van Beers, C. and Kleinknecht, A.

(2003). Success and Failure of Innovation: A Literature

Review. In International Journal of Innovation

Management, 7(3), 309–338.

van de Vrande, V., de Jong, J. P. J., Vanhaverbeke, W., &

de Rochemont, M. (2009). Open innovation in SMEs:

Trends, motives and management challenges. In

Technovation, 29(6–7), 423–437.

Veugelers, M., Bury, J., & Viaene, S. (2010). Linking

technology intelligence to open innovation. In

Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 77(2),

335–343.

Watanabe, C. & Fukuda, K. (2006). National Innovation

Ecosystems: The Similarity and Disparity of Japan-US

Technology Policy. In Journal of Services Research,

6(1), 159-186.

Westergren, U. (2011). Opening up innovation: the impact

of contextual factors on the co-creation of IT-enabled

value adding services within the manufacturing

industry. In Information Systems and e-Business

Management, 9(2), 223–245.

XAMK. (2019). XAMK on Suomen vahvin tutkimus- ja

kehittämiskorkeakoulu. Available: https://www.

xamk.fi/tiedotteet/xamk-on-suomen-vahvin-tutkimus-

ja-kehittamisammattikorkea/

Zhu, X., Xiao, Z., Dong, M. C., & Gu, J. (2019). The fit

between firms’ open innovation and business model for

new product development speed: A contingent

perspective. In Technovation, 86–87, 75–85.

Zirger, B.J. (1997) The influence of development

experience and product innovativeness on product

outcome. In Technology Analysis & Strategic

Management, 9(3), 287-297.

APPENDIX

Interview Questions

1. How is information shared within the ecosystem

and networks? Does information reach all actors?

2. What hinders active networking?

3. Are companies successful in forming partnerships

with businesses in the region?

4. Are the different actors communicating effectively

with each other?

5. Do the actors trust each other?

6. How do personal chemistries work within the

ecosystem?

5. Do actors within the ecosystem work only with

established partners or do they cooperate on a

broad scale?

6. What is the culture of the regional innovation

ecosystem?

7. What is the role of higher education in the region

and is there cooperation with businesses and other

actors?

8. Do the actors within the ecosystem share similar

goals and objectives?

9. Are there enough resources in the region to

maintain ecosystem functions?

10. Are different funding sources widely used?

11. How well do ecosystem actors tolerate risk in

general?

12. Is innovation part of the business culture and

strategy of companies in the region?

13. Do firms have experience in innovation?

14. Are firms closed or open to co-creation?

15. Are there sufficient R&D resources in the region's

enterprises?

16. Are firms' organizational structures generally

supportive of innovation?

KMIS 2023 - 15th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

184