Socio-Psychological Aspects of Childhood Creativity Development: A

Study on Unique Traits

Nozima Valieva

National University of Uzbekistan, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Keywords Children, Creativity, Parents, Mass Media, Socio-Psychological Characteristics, Factors, Creativity, Talent,

Family, Life Satisfaction.

Abstract This paper explores the socio-psychological facets associated with the growth of creative skills in primary

school children. The driving forces behind the enhancement of these creative abilities primarily include the

unique dynamics of family relationships and parental attitudes towards their children, the standing of siblings,

the nature of parent-child interactions, and the influence of media. This study also investigates the gender-

related differences in the development of creative abilities among primary school-aged children.

1 INTRODUCTION

In contemporary psychology, the issue of fostering

creative skills in primary school children remains

pertinent. The investigation has unveiled several

overarching aspects pertaining to the development of

creative abilities, which encompass a range of

biological and social factors contributing to the

emergence of this phenomenon in the analysis of

creative abilities. Nevertheless, there is currently no

unanimous consensus on the content and structure of

creative abilities, and even the very concept of

creative abilities lacks a clear definition, just as

comprehensive research on the factors influencing the

formation and growth of creative abilities in young

children of school age.

The objective of this study was to examine the socio-

psychological attributes associated with the evolution

of creative abilities in primary school children. The

research encompassed up to 300 young

schoolchildren.

2 METHODS OF RESEARCH

In our study, we employed the following

methodologies: the author's socio-psychological

questionnaire, "How did your child's imagination

*

Corresponding author

develop?", "Generalization of concepts",

"Methodology for studying Guilford's creative

abilities", and "Continue the signs" by Dyachenko

O.M.

During the initial phase of the research, a dedicated

socio-psychological survey was administered to

parents, followed by a statistical analysis based on

their responses to the survey questions. The socio-

psychological questionnaire, in total, comprised ten

questions.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

Questionnaire "How many children do you have?"

According to the responses, 3.3% of families have 1

child, 20.5% of families have 2 children, 55% of

families have 3 children, 17.9% of families have 4

children, 2.6% of families have 5 children, and 0.7%

of families have 6 children.

Regarding the question "How do parents assess their

children's creative abilities?", the findings revealed

that 50 (33.1%) parents rated their children's abilities

as "moderate," while 101 (66.9%) parents rated their

children's abilities as "high." Interestingly, the option

74

Valieva, N.

Socio-Psychological Aspects of Childhood Creativity Development: A Study on Unique Traits.

DOI: 10.5220/0012477700003792

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st Pamir Transboundary Conference for Sustainable Societies (PAMIR 2023), pages 74-82

ISBN: 978-989-758-687-3

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

for "low level" was provided, but no parent chose this

option.

When asked about the creativity of their children in

the family, the results were as follows: 66 parents

considered their first child to be highly creative, and

43 parents saw the second child as highly creative. In

terms of sibling status, 31 parents perceived their

third child as highly creative, and 9 parents regarded

the fourth child as highly creative (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Information on how many children in the family, according to parents' opinions, possess creative abilities

The analysis revealed the following results regarding

the number of children in the family and how many

of them are perceived by parents as possessing

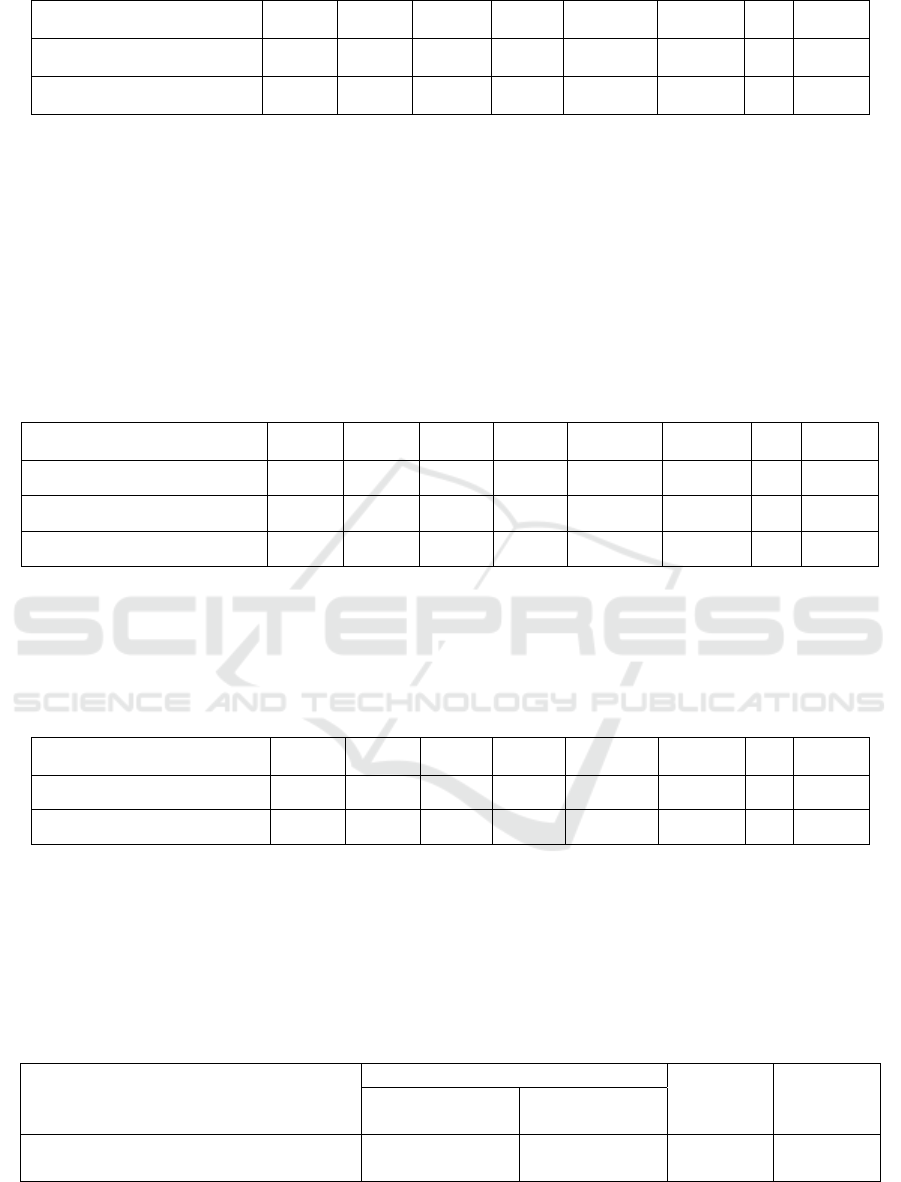

creative abilities (Table 1).

Table 1. Information on the number of children in the family and the perception of parents regarding the presence of creative

abilities

Children who possess creative

abilities in the family

Number of children in the family

Tot

al

1 2 3 4 5 6

1

st

Child

5

1

9

3

6

51 66

2

nd

Child

1

1

2

4

71 43

3

rd

Child

2

3

71 31

4

th

Child

81 9

5

th

Child

1 1

6

th

Child

1 1

Total

5

3

0

8

3

2

7

5 1 151

As depicted in this table, families with only one

child showed unanimous high appreciation for their

child's creative abilities. Among parents with two

children, 19 (approximately 63%) rated the creative

ability of the first child, and 11 (37%) rated the

second child. In families with three children, 36

(43%) parents acknowledged the creative ability of

the first child, 24 (29%) of the second child, and 23

Socio-Psychological Aspects of Childhood Creativity Development: A Study on Unique Traits

75

(28%) of the third child. However, the situation

changes significantly for families with four children.

Out of 27 parents with four children, 5 (19%)

recognized the creative ability of the first child, 7

(26%) of the second child, another 7 (26%) of the

third child, and 8 (30%) of the fourth child. This

indicates that families with four children tend to

overestimate the creative abilities of the later-born

children, especially the fourth child, rather than the

first child. Conversely, parents of five or more

children treated all their children equally without

making distinctions.

The subsequent question addressed the age at

which parents first noticed their children's creative

ability, revealing the following outcomes (Table 2).

Table 2: Information regarding the age at which parents first noticed their children's creative abilities

Age Amount Percent

1 year old 2 1,3

2 years old 8 5,3

3 years old 21 13,9

4 years old 16 10,6

5 years old 30 19,9

6 years old 23 15,2

7 years old 28 18,5

8 years old 15 9,9

9 years old 5 3,3

10 years old 3 2,0

Total 151 100,0

According to the data presented in Table 2, two

parents noticed their child's abilities at the age of one,

while eight parents noticed their child's abilities at the

age of two. Twenty-one parents observed their child's

abilities at the age of three, followed by 16 parents at

the age of four, 30 parents at the age of five, 23

parents at the age of six, 28 parents at the age of

seven, 15 parents at the age of eight, and another 15

parents at the age of nine. Three parents noticed their

child's abilities at both the ages of five and ten. This

suggests that most parents begin to notice their

children's creative abilities around the age of 5-7, just

before reaching school age.

Regarding the questions "Do you want your child

to achieve dreams that you can't achieve?" and "Do

you think my child should do what I want?", the

analysis of parents' answers showed the following

results. While 98% of parents want their child to

achieve dreams they could not, 93.4% of them

disagreed with the idea that "my child should do what

I want."

These opposing positions indicate that parents, on

one hand, want their children to fulfill dreams they

couldn't achieve, and on the other hand, they do not

expect their children to fulfill these dreams based on

their parents' desires; instead, parents expect their

children to achieve their own dreams through their

interests and efforts.

In response to the question "Are there conditions

in the family for the formation and development of

the creative abilities of your children?", 98.7% of

parents answered "yes," and only 1.3% of parents

answered "no." This implies that the majority of

parents strive to create conditions that foster the

development of their children's abilities.

Regarding the factors influencing the

development of creative abilities in children, 41

(19.3%) parents mentioned heredity, while 113

(53.3%) parents attributed a significant influence to

the family. Additionally, 38 (17.9%) parents cited

school as a reason for the development of creative

ability, and 20 (9.4%) parents cited the media as a

factor influencing children's ability. This suggests

PAMIR 2023 - The First Pamir Transboundary Conference for Sustainable Societies- | PAMIR

76

that most parents believe that family is one of the

most important factors contributing to the

development of creative abilities in children.

In conclusion, after analyzing the results of the

socio-psychological questionnaire administered to

parents of primary school-aged children, several

conclusions can be drawn. Psychodiagnostic

methodologies were conducted on primary school

students, and the initial statistical analysis of the

obtained data is presented below.

The statistical analysis of the Jenson Creativity

Survey scale results (Table 3) for 151 pupils revealed

the following: the minimum score is 8, the maximum

score is 40 points, and the average value for creativity

is 31.13. The scales of asymmetry (-0.872) and excess

(1.552) on the statistical distribution of this scale

indicate a slightly sharp tip, but overall, the data

obtained conform to the normal distribution law (Z =

1.16; p > 0.05).

Table 3: Statistical distribution of Jenson's creativity survey scale (Kolmogorov-Smirnov criterion, N = 151)

Scales

Minimu

m

Maximu

m

Average

.

Statistic

al

deviatio

n

Asymmetr

y

Excess Z р

Creativity

8 40 31,13 5,36 -0,872 1,552 1,16 0,138

Table 4: Indicators of statistical distribution of scales of PARI methodology (Kolmogorov-Smirnov criterion, N = 151)

Scales

Minimu

m

Maximu

m

Average Statistic

al

deviatio

n

Asym

metry

Excess

Z р

Verbalization

8 20 15,37 2,94 -0,373 -0,681 1,48 0,025*

Extreme caution

8 20 15,05 3,07 -0,347 -0,514 1,50 0,022*

Dependence on family

7 20 14,60 3,00 -0,344 -0,494 1,46 0,027*

Suppression of will

7 20 14,90 3,03 -0,424 -0,393 1,46 0,029*

Feeling of devotion

7 20 14,99 3,35 -0,440 -0,713 1,49 0,024*

Fear of offense

7 20 14,92 3,36 -0,489 -0,641 1,51 0,021*

Family conflicts

5 20 12,86 3,54 -0,065 -0,757 1,20 0,112

Irritability

7 20 14,28 3,18 -0,177 -0,573 1,32 0,061

Excessive persistence

5 20 12,24 3,62 0,056 -0,811 1,12 0,164

Exclude extra-familial influences

7 20 15,76 3,00 -0,88 0,431 2,06 0,000*

Excessive parental authority

7 20 16,38 3,32 -0,837 -0,265 2,10 0,000*

Suppression of aggression

7 20 14,91 2,79 -0,332 -0,213 1,09 0,185

Dissatisfaction with the role of

housewife

5 20 12,85 3,52 -0,32 -0,46 0,98 0,288

Partnership

8 20 14,95 2,84 -0,442 -0,242 1,76 0,004*

Develop the child's activity

7 20 15,71 3,04 -0,868 0,198 2,31 0,000*

Avoiding conflicts

5 20 13,63 2,98 -0,431 0,28 1,08 0,194

The negligence of the land

6 20 14,26 3,17 -0,295 -0,574 1,45 0,029*

Suppression of libido

5 20 14,61 3,62 -0,426 -0,736 1,80 0,003*

The superiority of the mother

5 20 13,48 3,54 -0,199 -0,535 1,17 0,129

Excessive intervention in the

child's worl

d

7 20 16,05 3,63 -0,861 -0,215 1,88 0,002*

Socio-Psychological Aspects of Childhood Creativity Development: A Study on Unique Traits

77

Balancing relationships

8 20 16,56 3,15 -1,027 0,394 2,11 0,000*

Striving to accelerate a child’s

development

5 20 13,23 3,75 -0,041 -0,866 1,09 0,190

Lack of maternal independence

7 20 15,27 3,33 -0,644 -0,235 1,51 0,021*

Note: * - p <0.05.

The results of the statistical distribution analysis of

the scales of the PARI methodology are presented in

Table 4. The scales "Verbalization" (Z = 1.48; p

<0.05), "Extreme caution" (Z = 1.50; p <0.05),

"Family dependence" (Z = 1.46; p <0.05),

"Suppression of will" (Z = 1.46; p <0.05), "Feeling of

selflessness" (Z = 1.49; p <0.05), "Fear of offending"

(Z = 1.51; p <0.05), "Exclusion of extra-family

influences" (Z = 2.06; p <0.001), "Excessive parental

authority" (Z = 2.10; p <0.001), "Partnerships" (Z =

1.76; p <0.01), "Development of Child Activity" (Z =

2.31; p <0.001), "Land Indifference" (Z = 1.49; p

<0.05), "Suppression of libido" (Z = 1.80; p <0.01),

and "Excessive interference in the child's world" (Z =

1.88; p <0.01) scales deviated from the normal

distribution rules. Consequently, in the later stages of

the study, it would be advisable to use non-parametric

criteria for processing the scales of the PARI

methodology. Similarly, the analysis of the statistical

distribution of scales of the "Talent Map"

methodology yielded the following results (Table 4).

The scales "Intellectual" (Z = 2.15; p <0.001),

"Creative" (Z = 1.61; p <0.05), "Academic

(scientific)" (Z = 1.50; p <0.05), "Fine Arts" (Z =

1.55; p <0.05), "Art" (Z = 1.45; p <0.05), "Technical"

(Z = 1.39; p <0.05), "Leadership" (Z = 1.87; p <0.01),

and "Sport" (Z = 1.64; p <0.01) scales were also found

to deviate from the law of normal distribution.

Therefore, in the later stages of the research, it would

be appropriate to utilize non-parametric criteria for

processing the scales of the "Talent Map"

methodology.

Table 5: Statistical Distribution Indicators of Scales in the "Talent Map" Method (Kolmogorov-Smirnov Criterion, N = 151)

Scales Minimum Maximum Average Statistical

deviation

Asym

metry

Excess

Z р

Intellectual

-8 16 9,23 5,86 -0,955 0,099 2,15 0,000*

Creative

-8 16 8,34 5,69 -0,86 0,201 1,61 0,011*

Academic

-8 16 7,36 5,69 -0,531 -0,495 1,50 0,022*

Fine arts

-8 16 7,80 6,32 -0,52 -0,794 1,55 0,016*

Musical art

-8 16 5,21 6,11 -0,081 -0,865 0,90 0,392

Fine arts

-8 16 6,07 6,21 -0,379 -0,782 1,45 0,029*

Artistic ability

-8 16 6,30 6,35 -0,23 -0,925 1,12 0,166

Technician

-8 16 5,10 6,61 -0,188 -1,022 1,39 0,042*

Leadership

-8 16 8,66 6,74 -0,703 -0,686 1,87 0,002*

Sport

-8 16 8,54 6,39 -0,595 -0,807 1,64 0,009*

Note: * - p <0.05.

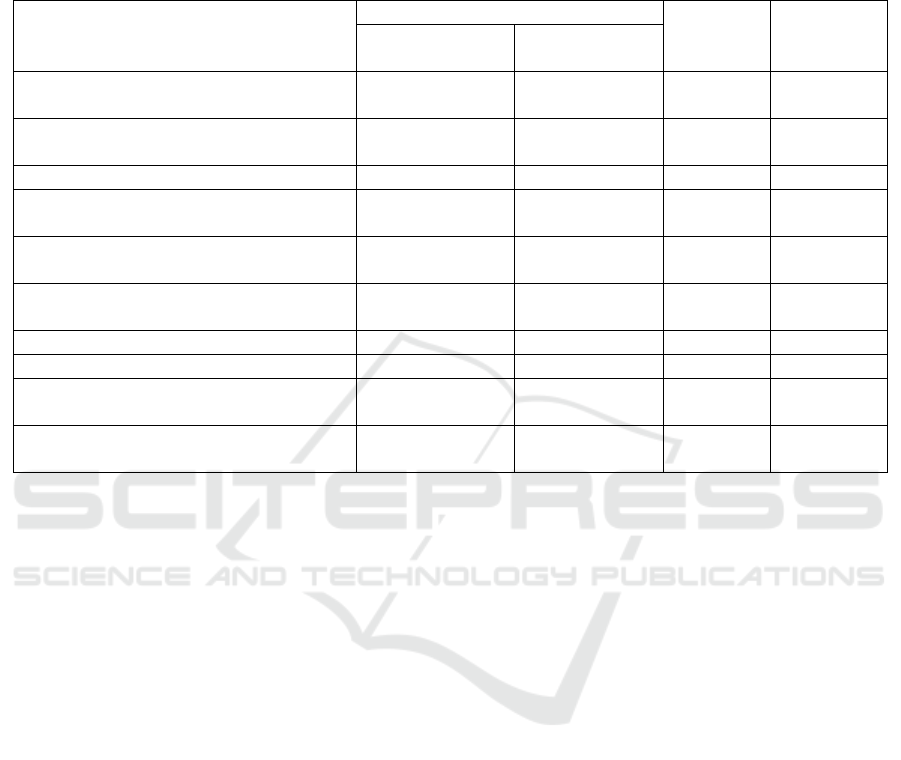

Table 6 shows the statistical distribution indicators of

E.S Hyubner's methodology "Determination of life

satisfaction of pupils".

Table 6: Statistical Distribution Indicators of Scales in the E.S Hyubner's Method "Determining the level of life satisfaction

of pupils" (Kolmogorov-Smirnov criterion, N = 151)

Scales Minimu

m

Maximu

m

Average Statistica

l

deviation

Asymmetry

Excess Z р

Family

4 6 5,79 0,44 -1,885 2,697 5,97 0,000*

School

2 6 5,53 0,76 -1,781 3,366 4,83 0,000*

PAMIR 2023 - The First Pamir Transboundary Conference for Sustainable Societies- | PAMIR

78

Teachers

2 6 5,40 0,87 -1,542 2,006 4,23 0,000*

Myself

1 6 5,55 0,84 -2,362 6,763 5,00 0,000*

My friends

2 6 5,55 0,75 -2,531 8,593 4,51 0,000*

Note: * - p <0.05.

As observed in the table, the data for "Family" (Z =

5.97; p <0.001), "School" (Z = 4.83; p <0.001),

"Teachers" (Z = 4.23; p <0.01), "Myself" (Z = 5.00;

p <0.001), and "My Friends" (Z = 4.51; p <0.001) do

not adhere to the rules of normal distribution.

Therefore, in the later stages of the study, it became

necessary to use non-parametric criteria when

developing scales for E.S. Hyubner's "Determination

of life satisfaction of pupils" methodology.

Table 7 presents the results of the statistical

distribution of the scales of Warteg's "Circles"

method. It can be observed that the scales for

"Thinking speed" (Z = 4.37; p <0.001), "Thinking

divergence" (Z = 2.43; p <0.001), and "Thinking

originality" (Z = 3.08; p <0.001) do not conform to

the rules of normal distribution. When dealing with

such a series of non-parametric numbers, it is, indeed,

appropriate to use non-parametric criteria.

Table 7: Indicators of statistical distribution indicators of Warteg's method "Circles" (Kolmogorov-Smirnov criterion, N =

151)

Scales Minimum Maximum Average Statistical

deviation

Asymmetry Excess

Z р

Speed of thinking

0 20 13,35 8,37 -0,605 -1,488 4,37 0,000*

Divergence of thinking

0 8 2,26 1,98 0,289 -1,035 2,43 0,000*

Originality of thinking

0 12 2,24 2,68 1,409 1,821 3,08 0,000*

Note: * - p <0.05.

Table 8 shows the statistical distribution indicators of the "Detection of external disturbances" method (adaptation

of A.M. Prikhojan).

Table 8: Indicators of statistical distribution indicators of the "Detection of external disturbances" method (adaptation of A.M

Prikhojan) (Kolmogorov-Smirnov criterion, N = 151)

Scales Minimum Maximum Average Statistical

deviation

Asymmetry Excess

Z р

Anxiety

3 42 21,58 7,59 -0,23 -0,431 1,04 0,233

False scale

0 10 5,91 1,96 -0,196 -0,458 1,49 0,024*

Note: * - p <0.05.

The primary scale of this method, known as

"Anxiety," conforms to the normal distribution of the

Kolmogorov-Smirnov criterion (Z = 1.04; p> 0.05),

whereas the false scale (Z = 1.49; p <0.05) is found to

be inconsistent with the rules of distribution.

The study also analyzed gender differences in

creative abilities among young school-age children.

No statistically significant difference was found in the

gender characteristics of the Jenson Creativity Survey

indicators (Table 9).

Table 9: Gender Differences on the Jenson Creativity Survey Scale (Mann-Whitney Criterion)

Scale

Average

U p

Boys

(N=61)

Girls

(N=90)

Creativity 72,5 78,4

2529,

5 0,413

Socio-Psychological Aspects of Childhood Creativity Development: A Study on Unique Traits

79

However, when examining the results of the "Talent

Map" methodology, notable gender differences

were discovered (Table 10).

Table 10: Gender difference indicators of the "Talent Map" methodology (Mann-Whitney criterion)

Scales

Avarage

U P

Boys (N=61)

Girls

(N=90)

Intellectual

67,1 82,1

2200,

5 0,038*

Creative

70,3 79,9

2397,

5 0,187

Academic 65,5 83,1 2105 0,015*

Fine arts

63,5 84,5

1981,

5

0,004*

*

Musical art

65,9 82,9

2126,

5 0,019*

Fine arts

65,7 83,0

2117,

5 0,017*

Artistic ability 66,8 82,3 2182 0,033*

Technician 85,0 69,9 2196 0,037*

Leadership

67,2 82,0

2207,

5 0,041*

Sport

75,7 76,2

2726,

5 0,944

Note: * - p <0.05; ** p <0.01.

As shown in the table, significant differences between

boys and girls were observed in terms of

"Intellectual" ability (U = 2200.5; p <0.05). In our

study, girls exhibited higher "Intellectual" abilities

than boys, which could be attributed to the age-related

characteristics of the subjects. Scientific literature

suggests that girls in primary school tend to have

higher levels of mental, emotional, physical, and

physiological development compared to boys.

Furthermore, girls also outperformed boys in

"Academic" abilities (U = 2105; p <0.05). Their

interest in various fields of knowledge and overall

curiosity are distinguishing characteristics among

girls in primary school.

When examining the "Fine Arts" scale, girls' abilities

significantly exceeded those of boys (U = 1981.5; p

<0.01). This difference can be attributed to the

psychological and physical maturity of young school-

age girls, which positively affects the development of

aesthetic abilities and psychomotor skills in them.

The heightened sense of aesthetics is also evident in

the way girls dress and present themselves.

Girls also exhibited higher performance in "Musical"

abilities (U = 2126.5; p <0.05) and "Artistic" abilities

(U = 2117.5; p <0.05) compared to boys. Overall,

girls demonstrated a higher level of artistic and

creative skills, reflecting their age-related

psychological characteristics. Surprisingly, girls also

outperformed boys in "Leadership" skills: U =

2207.5; p <0.05. This finding challenges the common

perception of leadership as predominantly a male

characteristic. Girls' advantage in leadership abilities

can be attributed to their physiological and

psychological maturity.

The only area where boys showed higher confidence

levels than girls was in "Technical" skills (U = 2196;

p <0.05). This result aligns with the general

understanding that boys tend to display a greater

interest in technical thinking and problem-solving

related to technology.

In the subsequent analysis, gender differences were

explored using ES Hyubner's "Determining the level

of life satisfaction of pupils" methodology. However,

no significant gender differences were found in the

level of satisfaction in family life, school life,

cooperation with teachers, activities, and

relationships with friends (Table 11).

PAMIR 2023 - The First Pamir Transboundary Conference for Sustainable Societies- | PAMIR

80

Table 11: Gender difference indicators of the E.S Hyubner's method "Determining the level of life satisfaction of pupils"

(Mann-Whitney criterion)

Scales

Avarage

U р

Boys

(N=61)

Girls

(N=90)

Family

73,4 77,8 2587

0,38

7

School

77,5 75,0 2652

0,67

3

Teachers

75,5 76,4

2711,

5

0,88

5

Myself

79,8 73,4 2511

0,27

0

My friends

70,6 79,7 2414

0,13

5

During the analysis of gender characteristics using

Warteg's "Circles" methodology, it was observed

that there are differences in the level of statistical

confidence (Table 12).

Table 12: Gender differences in Warteg's "Circles" methodical scales (Mann-Whitney criterion)

Scales

Avarage

U P

Boys

(N=61)

Girls

(N=90)

Speed of thinking

63,9 84,2 2009

0,002*

*

Divergence of thinking

60,7 86,4 1811

0,001**

Originality of thinking

71,3 79,2

2457,

5 0,249

Note: ** p <0.01.

As indicated in the table, there are statistically

significant differences in the level of confidence

between boys and girls on the "Thinking speed" scale

(U = 2009; p <0.01). Thinking speed is a vital

indicator of creative thinking, and quick thinking

often positively influences the development of quick-

witted and creative qualities. The exact speed of

thinking is a critical factor that impacts the

development of creative abilities in girls.

A comparative examination of gender differences on

the "Thinking divergence" scale revealed statistically

significant distinctions in confidence levels (U =

1811; p <0.01). Divergent thinking is widely known

as the ability to generate multiple solutions to a

problem. This suggests that girls hold a significant

advantage over boys in terms of their ability to

creatively find numerous solutions to any given

problem, as evidenced by their higher scores on this

scale. Although girls also outperformed boys on the

"originality of thinking" scale, the difference was not

statistically significant. In other words, while this

relatively rare trait is slightly more developed in

school-age girls than in boys, there are still boys who

can think originally and produce "untouched"

thoughts.

4 CONCLUSION

1. The assessment parents give to their children's

creative abilities is largely influenced by the birth

order of the children. Parents tend to believe more in

the high abilities of their first child and, to some

extent, in the abilities of their subsequent children.

However, as more children are born, these hopes may

diminish.

2. The perception of how many children in the

family possess creative abilities is influenced by the

family size. Families with up to 3 children often focus

more on the first and second child's creative abilities,

while families with four children tend to overestimate

Socio-Psychological Aspects of Childhood Creativity Development: A Study on Unique Traits

81

the creativity of the later-born children, especially the

fourth child, rather than the first child. Families with

five children treat their children more equally,

without distinguishing between them based on

creative abilities.

3. According to the majority of parents, one of the

most significant factors influencing the development

of creative abilities in children is the family

environment. "Heredity" and "school" are considered

the second and third most influential factors,

respectively. The media is seen as having the least

impact on the development of children's creative

abilities.

4. It has been established that the intellectual,

academic (scientific), fine art, musical, artistic, and

leadership abilities of primary school-age girls are

significantly higher than those of boys. Only in

technical skills do boys outperform girls. There were

no significant differences between boys and girls in

sports skills or in creative abilities of a more general

nature.

5. Girls have been noted to outperform boys

significantly in terms of thinking speed and

divergence, which are underlying aspects of creative

abilities.

6. The level of attention and care parents give to

their children's upbringing is positively correlated

with their appreciation of their children's creative

abilities. Parents who take child-rearing more

seriously tend to value and acknowledge their

children's abilities in various areas more.

REFERENCES

V. G. Berezina, I. L. Vikentev, and S. Yu. (2011).

Childhood of a creative person. St. Petersburg:

Bukovsky Publishing House, 60 p.

Bogoyavlenskaya D.B. (2018) Psychology of creative

abilities. M.,-321 p.

Vygotsky L.S. (1991). Imagination and creativity in

childhood / L.S. Vygotsky. M.: Pedagogy, 276 p.

Endovitskaya T. (2007)On the development of creative

abilities // Preschool education. No. 12. P. 73-75.

Polanyi M. (1981). The creative imagination // The concept

of creativity in science and art. - The Hague, Poweion

W.E. Creativity and competition // J. Creative behavior.

- 1982. - V. 16. - No. 2.

Prentry R.A. (1980). Creativity and psychopathology: a

neurocognitive perspective. - N.Y.

PAMIR 2023 - The First Pamir Transboundary Conference for Sustainable Societies- | PAMIR

82