The Function of Complex Sentences in the Prose of Alisher Navoi

S. Ashirboyev

Tashkent State University of Uzbek Language and Literature named after Alisher Navoi, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Keywords: Sentence, Parts of the Sentence, Subject, Simple Part, Complex Part, Extended Part, Persian and Arabic

Suffixes, a System of Words.

Abstract: Recently, the quantity of research into the history of the Uzbek language has declined, not due to a lack of

source material, but rather an absence of motivation in this area. There is a call for studies focusing on the

historical phonetics, morphology, and lexicology of Uzbek, particularly its historical syntax, which merits

fresh exploration. This paper examines syntactic phenomena within the language of Alisher Navoi, capturing

unique aspects of 15th-century Uzbek. We prioritise an analysis of complex sentence structure in Navoi's

prose, proposing a novel theory classifying sentence parts into two types: simple and complex. The complex

parts are recommended to include expanded, permanent compounds, Persian and Arabic suffixes, and word

series. This innovative classification in Uzbek linguistics is a first. The study also discusses the structural and

semantic peculiarities of the -ki//kim form, a sentence part significantly differing from contemporary Uzbek

and other related and unrelated languages.

1 INTRODUCTION

A fresh perspective is required in researching the

historical syntax of the Uzbek language. We

frequently refer to the works of Alisher Navoi when

discussing the history of the Uzbek language. Navoi's

works, dating from the 15th century, showcased the

vast potential of the Uzbek language, defining an

entire era. Consequently, the language, as shaped by

Navoi in his literature, has been globally

acknowledged as the old Uzbek literary language.

While we object to the term 'old Uzbek language', we

sometimes use it given its reference to the

internationally recognised classical Uzbek literary

language, and we endeavour to substantiate our

scientific views using this source. Specifically, we

elucidate and validate the issue of complex sentence

structure through the examination of the subject,

using factual material from Navoi's prose. Our

analysis of complex sentence structures in Navoi's

prose utilises methods such as synthesis,

substantiation, and notably the opposition method,

which effectively differentiates between simple and

expanded subjects.

*

Corresponding author

2 RESULTS

In traditional linguistics, sentences are thought to

have five parts. We maintain this categorisation in our

work, with minor amendments, particularly regarding

the attribute's position in sentence structure. Parts of

a sentence vary based on the structural and semantic

features of word forms, phrases, and other syntactic

units [Abdullaev F. (1974),2]. These elements serve

to convey certain semantics. However, structure and

semantics alone are insufficient to differentiate

sentence parts; they must also be viewed as

constructive-functional sentence elements

[Abdullaev F., Yusupov M. (1981)]. This

differentiation approach is preferred, though it does

have contentious issues.

There is consensus in Uzbek and broader Turkic

language research on defining primary sentence parts.

Debate remains over designating an attribute from

secondary sentence parts, and difficulties exist in

identifying the object and modifier. Numerous

suggestions exist for naming the structural and

semantic features of sentence parts in Uzbek

linguistics, too numerous to list. However, we find A.

Hojiev and N. Mahmudov's recommendation to use

the opposition method valuable: unextended part ↔

S. Ashirboyev, .

The Function of Complex Sentences in the Prose of Alisher Navoi.

DOI: 10.5220/0012483100003792

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st Pamir Transboundary Conference for Sustainable Societies (PAMIR 2023), pages 213-220

ISBN: 978-989-758-687-3

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

213

extended part, simple part ↔ complex part, single-

component part ↔ multi-component part, etc.

[Abdurahmanov G., Sulaymanov A., Kholyirov H.,

Omonturdiev J. ,(1979)]. Conversely, J. Omonturdiev

disagreed with the term 'extended part' [Ashirboev S.

(1990)]. We propose a universal classification pattern

for all sentence parts' internal structural properties:

simple and complex. It's worth noting that in

historical language studies or source syntax work, all

instances of simple sentence parts are included. We

argue that such practice is outdated in the context of

contemporary Uzbek language theory and lacks

scientific value. Accordingly, while citing simple

sentence parts in research may be outdated, studying

the semantics of sentence parts within historical

language texts remains scientifically significant.

Summarising all types of sentence parts comprising

two or more word forms in their structural features,

we propose calling them complex sentence parts.

Given their use across languages and historical

periods, it's expedient to analyse their structural and

semantic properties scientifically. This article

examines the complex part pattern relating to the

subject expression. We first need to classify the

complex sentence parts. Based on the subject

examples in Alisher Navoi's prose, we classify them

as follows:

1. Extended part: Characterised by word

combinations, verbal adverbs, participles, and

gerunds. Some contain transformed speech parts

[Ashirboev S. (1990)]. The key feature is the free

syntactic relationship of the word forms. Notably,

A.N. Kononov and V.G. Kondratev argue that the

extended part's dominant word is solely verb forms

[Baskakov N. A. (1975)]. While unchallenged, it

seems inappropriate to limit the dominant component

of extended parts to verb forms. Any independent

word group can participate in this position. Examples

follow.

2. Part comprising a stable compound: These parts

have free syntactic relations, but the compound is

fully lexicalised.

3. Part containing Persian and Arabic suffixes: This

will be explained in detail later.

4. Part composed of a word series: Here, the syntactic

relationship between words gives an impression of

comprehension, but they are non-functional and

represent a complex concept. These parts mostly

relate to word sequences expressing a person's name

and lineage.

This classification also applies to the subject, object,

and modifier, with unique structural and semantic

types according to the predicate's application

features, which we'll detail in future work. We believe

this classification will interest researchers of Turkic

and non-Turkic languages.

In this article, we illustrate the structural and content

features of complex sentence parts, focusing on the

subject forms not present in contemporary Uzbek and

other languages.

The subject, denoting the thought object and speech

subject, is integral. Its semantic properties stem from

the semantics of the word forms or compounds

expressing it. V.G. Gak contends that the sentence's

primary semantics is it being the action executor,

inferred sign from the predicate, and state bearer

[Bashmanov. M. (1982) -11]. This is demonstrated

when the subject is represented by nouns denoting

living subjects: Va Shayx Ibrohim Ojariyki, xisht

ulabdur, 'Shayh Ibrohim laid a brick' (NM 3).

From the above description, we can list several

characteristics specific to the subject in Alisher

Navoi's prose:

1. It denotes the subject of action, state, and sign.

Such a subject is primarily characterised by adjectives

and participles: Hamul besh-o‘n kunda abtar

devonani bo‘zaxonada yana bir abtar bo‘ynini chopib

o‘lturdi (XM 27).

2. It indicates the subject of the action object: Vazirga

bu xabar yetishti, 'the ministers received this

message'. (Nas. 97).

3. It signifies the subject of the action place: Va ul

hazratning muborak marqadi Jom viloyatida Xarjurd

qasabasidadur, 'And his blessed grave is in the city of

Harjurd in Jam province'. (NM 6).

4. It indicates the subject of the action or sign's time:

Va Yaloshning zamoni besh yildin juzviy o‘ksukdur,

And the sovereignty of Yalosh is less than five years.

(TMA 60).

5. It represents the subject of the action or sign's

cause: Mulk ochmog‘ining jihati ul bo‘ldi, 'this was

the reason for the conquest of the states' (TMA 17).

Structural Features of the Subject: It is known that the

subject is a crucial component of a simple sentence

with two main parts. However, instances of implicit

subjects are also evident in the works of Alisher

Navoi, mirroring the modern Uzbek language, as

there are instances where the subject's position in the

sentence remains vacant. Statistical data supports this

perspective. Upon examining four works by Alisher

Navoi, we observed the following: the subject in the

simple sentence was not utilised in 158 instances in

Majolisun nafois, 18 in Muhokamatul lug'atayn, 51 in

Tarihi muluki Ajam, and 101 in Mahbubul qulub.

Before analysing the complex part of the subject in

Alisher Navoi's works, it seemed appropriate to

introduce some fundamental principles regarding the

PAMIR 2023 - The First Pamir Transboundary Conference for Sustainable Societies- | PAMIR

214

usage of simple sentences in the writer's works. This

is because they serve as a dominant component in the

structure of a complex part of the subject:

1. It is represented by a common noun: "Saxovat

insoniyat bog‘ining borvar shajaridur, generosity in

humankind is a tree that gives fruit" (MQ 100).

2. It is represented by a proper noun: The usage of the

proper noun as a function of the subject is

characteristic in Alisher Navoi's works: "Miri

majlisdag‘i ahli majlisqa muttafiq bo‘ldi, 'Miri agreed

with the opinions of those participating in the

meeting'" (XM 5).

3. It is represented by the noun in the form of "yoye

nisba" and "yoye ishorat": "Odami til bila soyir

hayvondin mumtoz bo‘lur, humans differ from

animals through language" (MQ 126).

4. It is expressed by substantive adjectives: "Nodon –

eshak, balki eshaktin battarrak, foolishness is a

donkey, perhaps worse than a donkey" (MQ 133).

5. It is characterised by an adjective in the Arabic

plural form: "Atbo'i qalin, his dependents are

numerous" (XM 42).

This analysis provides an understanding of the

complexity of subject structures within Alisher

Navoi's works. Additionally, it highlights the need for

a concept that can encapsulate complex subject

forms, such as those characterised by several word

forms or those containing inextricably linked words.

This concept seems relevant not only for modern

analyses but also when examining classical works

like those of Alisher Navoi. It is therefore advisable

to consider subjects with these features as complex

subjects in Navoi's works.

For instance, consider the sentence: "Bu she'rga

hazrati Maxdumi Nuran javob aytibdurlar va otin

'Lujjatul asror' bitibdurlar, 'Hazrat Mahdumi Nuran

responded to this poem and titled it as 'Lujjatul Asror''

(ML 25)." Here, it is not possible to analyse or

question the individual words in the application of

"Hazrat Mahdumi Nuran" which occupies the

position of the subject. This observation suggests that

it isn't always necessary to differentiate between the

attribute-substitution relations in compounds, as seen

in the sentence: "Ammo bu toifani haq taolo noqisi

vojib yaratibdur (MQ 56)."

Depending on the relationship of the words in the

composition, the following forms of the complex

subject can be identified:

1. Although the attribute-substitution relationship is

noticeable, it is not necessary to differentiate, that is,

to analyse them: 'Kichik Mirzo alayhirrahma ul

viloyattin o‘tarda bu azizning mazkur bo‘lg‘an sifotin

eshitib, aning ziyoratig‘a yetti' translates as 'Kichik

Mirzo alayhirrahma, having heard good things about

this revered person, visited him when he travelled to

this province' (MQ 60).

2. The word 'binni', indicating the generation, is

involved in the structure: 'Bahrom binni Shopur

otasining vasiyati bila saltanat taxtig‘a o‘lturdi'

translates as 'Bahrom bin Shapur ascended the throne

following his father’s last will' (TMA 57).

3. Arabic suffixes and the word 'binni' are used:

'No‘shiravonul odil binni Qubod chun saltanat taxtin

musharraf qildi' translates as 'When Noshiravonul

odil binni Qubad ascended the throne' (TMA 62).

4. It consists of Arabic suffixes: 'Dorul mulki

Madoyin erdi' translates as 'Madoyin was the capital

of the country' (TMA 63).

5. It consists of Farsi suffixes: 'Bahromi Cho‘bina

mutag‘ayyir bo‘lub, anga yog‘i bo‘ldi' translates as

'The opinion of Bahromi Chobina changed, and he

became his enemy' (TMA 68).

The issue of the extended subject's naming, syntactic

and semantic nature remains controversial in Uzbek

linguistics. The phenomenon known as 'razvernuty

chlen' or 'razvitoy chlen' in the field is referred to in

Uzbek linguistics by the terms 'extended part',

'compound part' [Syntax. - Tashkent:

Science,(1966).], 'subject represented by syntactic

compounds' [Ghulomov A.G., Askarova M.A. (1965)

- Hojiev A., Mahmudov N. (1983)], and there are

even views that the subject expressed in syntactic

phrases [ML – Alisher Navoi. (1941)]. Nazarova,

who researched the syntax of the work "Boburnoma",

also referred to the extended subject as

'rasprostranenniy chlen predlojeniya' [Syntax. -

Tashkent: Science,(1966).]. Although it is advisable

to use the term 'extended part' when naming this

phenomenon, coining the term should not be the main

issue for discussion in linguistics. On the contrary, it

would be preferable to focus on the scientific

regulation of the theory of that phenomenon. Due to

this, the term 'extended part' should be specific to the

event it represents.

In Uzbek linguistics, there are also supporters who

deny the existence of the extended part phenomenon

[ML – Alisher Navoi. (1941)]. Such a view is also not

correct because, although the parts of sentences are

formally and grammatically separate, the meaning of

the word form is one of the bases of its definition. In

other words, all lexical and grammatical peculiarities

of the word forms entering into the syntactic

relationship in the sentence are taken into account

[MN – Alisher Navoi. (1961)]. In defining the

extended subject (although he does not use the term),

he considers its relation to the predicate. In addition,

he gives examples such as 'three children have gone',

'ten children are sitting'. It is noteworthy that in these

The Function of Complex Sentences in the Prose of Alisher Navoi

215

sentences, the word 'child' itself cannot express the

subject of thought; in this case, not only the child but

also 'three children' and 'ten children' together express

the subject of the sentence. It is known that such a

view aligns with the goals of semantic syntax. In

linguistics, the notion has long existed that not just a

word form, but also an entire syntactic group can

become parts of sentences, and these views continue.

From this perspective, in the work "the current Uzbek

literary language", in the sentences 'Bizga aqli o‘tkiri

kelsin. Odil ko‘rgan odam shumi?', it is rightly stated

that in the position of the subject it is necessary to

denote not only the words 'o‘tkiri', 'odam' but also the

combinations 'aqli o‘tkiri', 'Odil ko’rgan odam'. We

would like to emphasise once again that it would be a

primitive approach to separate the word form used in

the nominative case from the context of the sentence

and determine its position in the sentence. We would

stress that any part of a sentence should be considered

from the point of view of the fulfilment of a logical

function concerning the predicate of the word form or

combination, which must be distinguished as the

content direction of the sentence and the part of the

sentence. Furthermore, the syntactic groups in the

composition of the subject that have their attribute

(sometimes a secondary part of the sentence) cannot

hold a relatively independent position, but rather they

integrate completely into the composition of the

subject's content. This syntactic-semantic

relationship occurs in other parts as well.

In the sentence, which has unified subjects, each

union component, if it is in the form of a phrase, the

word forms in that structure will be in a free syntactic

relation, and the dominant component will be in a

relationship of compatibility, cohesion, and

management with subordinate word forms. This

viewpoint is specific to the composition of each

unified subject, and it means the micro-syntactic

relation in them, that is, the internal syntactic

relationship for each syntactic group: 'Lozim ko‘rundi

turk tili sharhida bir necha varaqqa zebi oroyish

bermak va anda hazrat sultonus salotin muloyimat

tab' va mahorat zehnlaridin sharh yetmak va

humoyun roylari tartib bergan devon bobida bir necha

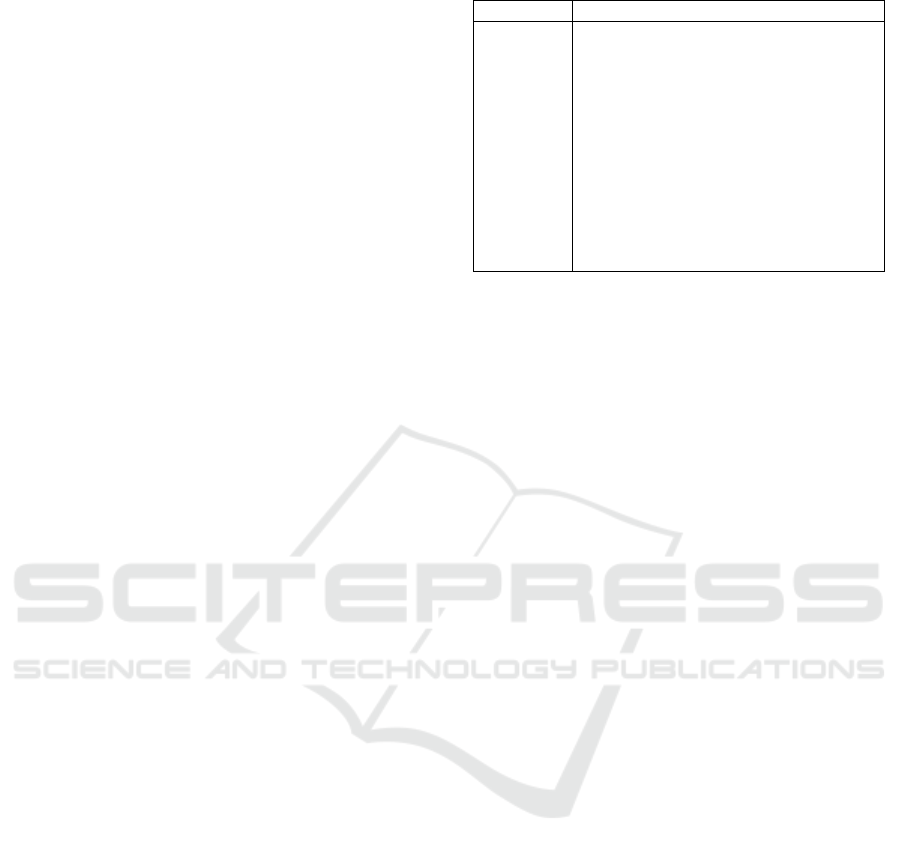

so‘z go‘stohliq yuzidin surmak' (MQ 37) (Table 1)

Table 1: This sentence can be described as follows

p

redicate United sub

j

ects

Lozim

ko‘rundi

‘It is

necessary’

turk tili sharhida bir necha varaqqa zebi

oroyish bermak ‘to give a comment to

the Turkish language in several pages’

anda hazrat sultonus salotin muloyimat

tab’ va mahorat zehnlaridin sharh

yetmak ‘to comment on the works and

skills of the King’

humoyun roylari tartib bergan devon

bobida bir necha so‘z go‘stohliq yuzidin

surmak ‘to give opinion about the

Devon which was written with his

favorite words’

In the given sentence, the infinitive, which is the

subject along with the dominant component and its

subordinate components, expressed the subject of the

sentence in relation to the predicate. In all instances,

the dominant component, consisting of the infinitive,

entered into a managerial relationship with the

subordinate component.

We can observe that it is straightforward to identify

the extended subject in such applications, but it is

challenging to determine the relatively independent

position of syntactic groups in instances where the

united subject has not participated. Another difficulty

arises in determining whether they form content

integrity with the dominant component. In such

situations, it has been demonstrated that it is

necessary to employ the opposition method. This

method involves separating the word in the general

case from the compound in which it participates and

determining its relation to the predicate, or the

compound as a whole is related to the predicate. In

this opposition, whichever syntactic phenomenon can

represent the subject of the sentence should be

acknowledged as the subject. This method can be

better appreciated in the following analyses:

'Va bu so‘zning tanavu'i taaqquldin nari va

tasavvurdin tashqaridur', which translates as 'And the

meaning of this word is beyond comprehension and

imagination' (ML 2). 'Bu munosabat bila arab

salotinidag‘i Ibrohim Mahdiydek va Ma'mun

Xalifadek va bulardin o‘zga ham salotinzodalar

g‘arro nazmlardin qasoyid ayttilar va qavoyid zohir

qildilar', translates as 'In this regard, like Arab sultans

Ibrahim Mahdi and Ma'mun Khalifa, and other

sultans wrote poems and created novels' (ML 33

In these two sentences, we describe the practice of

determining the word forms and phrases in the subject

position. In the first sentence, the subject of the

speech isn't clear when the word form is used in

relation to the predicate, i.e., when the word is used

outside the realm of comprehension and imagination.

PAMIR 2023 - The First Pamir Transboundary Conference for Sustainable Societies- | PAMIR

216

However, when in the form of the word, it can clarify

the predicate.

Conversely, in the use of 'salotinzodalar g‘arro

nazmlardin qasoyid ayttilar va qavoyid zohir qildilar',

the word form 'salotinzodalar' can express the subject

of independent speech. Even then, the subject of the

speech, the subject in the sentence, remains unclear.

This is because the word form in the attributive

position relative to the form of the word, which is

defined as the subject, is not a practical part of the

sentence.

In the following sentence, the word in the general

case cannot occupy the position of the subject: 'Va

aning zamonidagi anbiyo Uzayir bila Urmiyo va

Doniyol alahissalom erdilar', which translates as

'Uzayir, Urmiyo, and Doniyol alahissalom lived at

that time' (TMA 18). It's impossible to assume the

word 'anbiyo' as the subject because it cannot denote

a predicate 'Uzayir bila Urmiyo va Doniyol

alahissalom erdilar'. This syntactic group occupies

the position of the subject.

As is known, Persian and Arabic suffixes are widely

used in the classical Uzbek literary language [MQ –

Alisher Navoi. (1948) ]. These syntactic groups

maintain their syntactic position in the mentioned

languages. They preserve the feature of attribute-

attributed. However, it's not challenging to notice that

in the classical Uzbek language, a certain level of

lexicalisation began. Therefore, such syntactic groups

also participate in one syntactic position in the works

of Alisher Navoi: 'Bu ishtin xoqon-i turk voqif

bo‘lub, cherik tortib, Jayhundin o‘tub, aning

viloyatig‘a daxl qildi', which translates as 'the

Haqqan-i-Turk became aware of this, he lined up the

troops, he crossed the Jayhun river and invaded his

province' (TMA 54).

In determining the extended subject in "Boburnoma",

H. Nazarova associates them (the subject considered

the dominant component) exclusively with words that

have the suffix –lik (along with its other variants,

participle, and the name of the action or gerund [HM

– Alisher Navoi.]. She then transforms such subjects

into the defining basis of the material of expression.

However, in addition to the word forms outlined by

H. Nazarova, other forms of the noun, such as

pronouns and adverbs, can also participate in the

dominant component of the subject. In our view, the

material expression doesn't play a significant role in

the syntactic construction; rather, the syntactic

position and semantics are critical. In other words, a

part is determined as the subject of the sentence if it

can express the subject of the speech, irrespective of

whether it is represented by a word form or by a

phrase.

We'll look at the structural characteristics of the

extended subject. We base our understanding on the

concept of the dominant component in traditional

linguistics and examine it in terms of the syntactic

relationships of the word forms in the composition of

the extended subject.

The syntactic structure of the extended subject, with

its dominant component represented by the noun, is

as follows

1. The extended subject within the frame of attribute

– substitute (adjective noun). Cohesion relationship is

reflected here. Its subordinate component includes

word forms belonging to different parts of speech,

such as:

- Adjective. Bihamdilloh, burung‘i davlat muyassar

bo‘ldi, 'Thank God, the former state has returned'

(MSh 20). Xushnavis kotib so‘zga oroyish berur...

'The calligrapher with beautiful handwriting adores

the word' (MQ 30).

- Noun as an adjective: Forsigo‘y shoir munungdek

g‘arib mazmun adosidin mahrum, 'Poets who write in

Persian cannot express such a meaning' (ML 9).

- Pronoun. Ul tifl Iskandar erdi, 'That boy was

Iskandar' (TMA 27).

- Numeral. Anga otasidin yigirmi ming dirham

meros qoldi, 'Twenty thousand dirams were left to

him as inheritance from his father' (NM 89).

- Adverb. Baso tiflki ayni muhabbattin ota soqoli

tukin tortib uzubdur, 'Frequently, children tear off a

strand of their fathers’ beards because of their love for

them' (NM 89).

2. The extended subject in the frame of attribute –

substitute (possessive relationship). The material

expression of the indicator in this construction is:

- Noun. Bahmanning otasi talut naslidin erdilar,

'Bahman's father was of Talut descent' (TMA 21).

- Pronoun. Alarning viloyati ko‘p erdi, 'They have

many regions' (NM 135).

- Verb forms. Safurag‘a tug‘urur dardi paydo

bo‘ldi, 'Safura’s time to give birth has come' (TAH

340a).

In Alisher Navoi's prose, it is also noted that a word

with an implicit marker, that is, one possessing an

affix due to a marker in speech, can also take the

position of an extended subject: Ko‘ngli bu darddin

buzuldi, 'He was upset by this pain' (NM 10).

Yoshingiz uzun bo‘lsin, 'May you live long' (MSh

22).

3. Extended subject consisting of a Persian suffix:

Podshoh-i zamon Mirg‘a xiroj hukmi qildi, 'Podshoh

ordered Mir to leave the country' (MN 5).

4. Extended subject in the frame of object-predicate.

HK manages the word forms in the place case:

The Function of Complex Sentences in the Prose of Alisher Navoi

217

Majlisida nag‘manavozliq ilmu taqvo g‘izosig‘a

navhasozliq, 'Talking nonsense in a meeting is like

crying' (MQ 15). Mushukka rioyat kabutarg‘a

ofatdur, 'To do good to a cat is to do evil to pigeons'

(MQ 122).

Such compositions exist not only in classical Uzbek

literary language but also in the current Uzbek literary

language [Abdullaev 1974, 27; Abdullaev,

Ibrohimova 1982, 23], yet there are no viewpoints on

the syntactic situation causing it. In our opinion, the

emergence of such a syntactic condition is because it

undergoes ellipsis in this small syntactic position (that

is, the combination that appears in the subject

position), signalling the start of the transition from the

analytic form to the synthetic form. This is more

evident in the following sentences: Shohqa sipoh

darveshlar duosidur, fuqaro himmati va tengri

rizosidur, 'the prayers of the dervishes, the generosity

of the citizens and the approval of God will go to the

soldiers who serve the king' (MQ 17). Yomonlarg‘a

lutfu karam yaxshilarg‘a mujibi zararu alam, ‘dealing

with bad people harms good people’ (MQ 122).

In the position of shohqa sipoh and yomonlarg‘a lutfu

karam, had they been restated as shohqa sipoh bo‘lish

and yomonlarg‘a lutfu karam qilish, we would

consider it structural verb management rather than

noun management. However, the viewpoint of noun

management appears to be true if it is considered not

from the standpoint of the normal completeness of

written literary language but from the viewpoint of

the influence of spoken language on classical Uzbek

literary language. This is because ellipsis is a feature

of spoken language, and the syntactic phenomenon

reflected in practice is analysed.

The words in the place case that appeared in the text

as part of shohqa sipoh, yomonlarg‘a lutfu karam,

majlisida nag‘manavozliq, mushukka rioyat can be

considered as a determinant part. However, as

Bashmonov pointed out, it doesn't mean that there's

no syntactic connection (managerial relationship)

with the second part of the sentence or that it's a

secondary part [HPM - Alisher Navoi] that is

independent in its own right and fully related to the

sentence. Rather, such word forms constitute a direct

subject structure, though the syntactic connection

between them (dominant and subordinate

component) is weakened. In this respect, the

viewpoints of V.V. Babaytseva and L. Yu. Maksimov

hold true [28].

Such a determinant relationship is observed not only

in the extended subject comprised of two components

but also in the extended subject composed of multiple

components: Holo Pahlovon o‘rnida qoim maqomi

uldur, ‘He is a person who replaced Holo Pahlovon’

(MN 163). In this sentence, the transformed phrase

holo Pahlovon o‘rnida qoim maqomi occupies the

subject position. The dominant component (qoim

maqomi) governs the phrase holo Pahlovon o‘rnida,

but the management relationship between them is

weakened.

It is well known that word forms in a sentence can't

be syntactically independent, yet there are instances

where the syntactic relationship between them

becomes disconnected. Some of these even go

beyond the limits of the sentence (except for the

introductory part and the introduction), making it

impossible to consider them as part of the sentence.

As a result of this, when thinking about the

determinant part, one can only consider the

weakening of the syntactic connection between the

dominant and the subordinate part in the micro

syntactic position. The extended subject with a

determinant relation can be used specifically:

Faqirg‘a taajjub ustiga taajjub voqe' bo‘ldi, ‘To me, it

was an incident that surprised me’ (HPM 385a). It is

clear that in this sentence, the combination of faqirg‘a

taajjub ustiga taajjub appears in the subject position,

creating a non-standard state and entering into a

formal management relationship with the word

subordinated to faqirg‘a, so it can also be referred to

as a weak relationship.

Previously, we discussed the two-component

structure of sentence parts where the noun served as

the dominant component. In Alisher Navoi's prose,

three or more types of structures exist in phrases like

"the owner of the horse", which significantly

complicates its structure. Similarly, in Navoi's works,

there are three or more types of structures in the

extended subject, which undoubtedly add complexity

to the composition. Since the syntactic relationships

between them reflect the framework of the two-

component complex subject, they have not been

analysed in terms of their syntactic relations.

However, we would like to provide some examples:

Three components: Bovujudi, bu ikki misra' bir-

biriga marbut emas, ‘Unfortunately, these two

phrases are not connected to each other’ (MN 240);

Four or more components: Muncha g‘ayri mukarrar

xalq Said davlatidin shuarog‘a mamduh bo‘lubdur,

‘A certain category of people have been praised in the

Said’s state’ (MN 52). Mundoq nosih so‘zin

eshitmaganning sazosi taassuf yemak va o‘ziga

nosazo demak, ‘Not hearing the advice of such a

person does harm to oneself’ (MQ 141).

The complex subject's dominant component is

expressed by an adjective. They enter into a cohesive

and managerial relationship:

PAMIR 2023 - The First Pamir Transboundary Conference for Sustainable Societies- | PAMIR

218

Cohesive relationship: Subordinate words, adjectives,

participles, adjectival nouns, numerals, pronouns can

take part: Ko‘rungan qaro xud dasht bahoyimi edi,

‘The appearing thing was the steppe animal’ (TMA

27). Bir kecha ikki o‘g‘ri ittifoq qilibdur, ‘One night,

two thieves made an agreement’ (NM 4);

Managerial relationship: Biligiga mag‘rur – bilur elga

ma'yub va tengriga maqhur, ‘A person who is proud

of their knowledge incurs anger and indignation from

both God and people’ (MQ 107).

Such a subject consists of three or more components:

Bu nav' ko‘p bexirad nodonlar ... azizu sharif umr

tarkin qildilar, ‘Many foolish people at this level are

wasting their valuable and precious lives’ (MQ 105).

The complex subject's dominant component is

expressed by a numeral. In the part of the sentence

with such a structure, the subordinate word in the

ablative case takes part and it adopts the meaning of

the accusative case [Qodirov 1977, 20]. Two or more

types of structures of such a complex subject are used:

Alardin biri anga zahr berib halok qildi, ‘One of them

killed him with poison’ (TMA 33).

The complex subject's dominant component is

expressed by the pronoun. Oqibat Kayxisrav o‘zi

azim cherik tortib yurudi, ‘As a result, Kayxisrav

himself lined up his great troops and declared war’

(TMA 15).

The complex subject's dominant component is

expressed by forms of the verb. In this case, the name

of the action (gerund) and the participle are

considered. These functional forms are used in forms

that carry the possessive affix and do not change: Va

ro‘za tutmoq andin sunnat qoldi, ‘Fasting became a

habit for him’ (TMA3). Eranlar yasanmog‘ikim

namoyish uchundur, xotunlar bezanmog‘idekdurki

oroyish uchundur, ‘The making of men is equal to the

making of women’ (MQ 100). Xato va sahvin anglab

mutannabih bo‘lg‘an saodatmand odam-i-dur, ‘The

man who recognises his small mistake is a happy

man’ (MQ 143).

The structure of the subject utilises the form -ki //

kim. In the works of Alisher Navoi, there exists a

unique phenomenon that is not found in other

languages, including current Uzbek literary language:

the use of the formant -ki // kim in the subject's

structure. It can be stated that such usage is exclusive

to Alisher Navoi. Predominantly, there are

perspectives suggesting that the formant -ki//kim

links compound sentences and functions as a particle

in modern Uzbek literary language, which doesn't

necessitate specific commentary. However, there is

no analytical view in academic literature concerning

the usage of this form in the subject's composition and

the syntactic groups pursued in Alisher Navoi's

works. This can be observed in the following

examples:

1. The explanation ensures the presence of structures:

Va uch tilki, turkiy, forsiy va hindiy bo‘lg‘ay, bu

uchovning avlodu atbo'i orasida shoe' bo‘ldi, ‘The

three languages, Turkish, Persian and Indian, are

related to one language tree according to their origin’

(MQ 5). In this sentence, the phrase turkiy, forsiy va

hindiy bo‘lg‘ay elucidates uch til that came in the

position of subject, identifying what languages they

are. The formant -ki in the subject's composition in

this sentence ensures the existence of this explanatory

construction.

2. It facilitates the presence of an introductory phrase.

Bu nav' kishiki, anga mundaq bo‘lg‘ay kirdor, bu

davrda mavjud va hozir bor, ‘There are people of such

nature’ (MQ 103).

3. It ensures that the commentary and introductory

phrase are used together: Va Ashkim, Dorobning

o‘g‘li erdi va Iskandar zamonida vahmdin yoshurun

yurur erdi, anga xuruj qilib, ani o‘lturdi va taxt bildi,

‘And Ashkim was the son of Dorob, and in the time

of Alexander he hid in fear, attacked him, killed him,

and took the throne’ (TMA 32). In this sentence, the

construction Dorobning o‘g‘li erdi is an explanatory

construction, whereas the construction Iskandar

zamonida vahmdin yoshurun yurur erdi is an

introductory construction that provides additional

information about Dorob.

4. It ensures that the predicates in the sentence

transformation come together: Dehqonki dona

sochar, yerni yormoq bila rizq yo‘din ochar, ‘The

peasant sows seeds in the ground and thereby earns

his sustenance’ (MQ 46). In this sentence, the

constructions dona sochar, yerni yormoq bila rizq

yo‘din ochar are the combined predicates in the

sentence transformation. Actually, it's impossible to

form a sentence in this manner: Dehqonki dona

sochar, yerni yormoq bila rizq yo‘din ochar.

5. It ensures the presence of a simple and complex

predicate: Bovujudi, bu bekning sipohiyliqda jalodat

va bahodurlig‘in har kishikim tanir va musallam tutar,

‘By the way, everyone acknowledges and appreciates

the bravery and nimbleness of this prince in the army’

(MN 181).

6. It indicates the emphasis of the subject: Zihi,

muvaffaq bandaiki uldur, ‘This person has achieved

all successes’ (MN 117)

The formant ki//kim can join any syntactic form and

group that appears in the subject's position:

- To the word denoting a person: Muftiki hiyla bila

fatvo tuzar, ilm no‘gi bila shariat yuzin buzar, ‘If the

Mufti issues a fatwa by deception, he will break

Shari'at in this way’ (MQ 25);

The Function of Complex Sentences in the Prose of Alisher Navoi

219

- To the word denoting an unclear meaning:

Maqsudki pir irshodidin ayru bu yo‘lg‘a qadam

urmamaq kerak, balki dam, ‘It is not necessary to act

against the teacher's wishes’ (MQ 153);

- To the pronoun: Bu da'vog‘a ulki ravshani dalildur,

“ashobi fil” voqeasi bila tayron abobildur, ‘The

clearest evidence for this claim are the events “ashobi

fil” and “tayron abobil”’ (MQ 106);

- To the complex object: Otashin yuzluk mug‘anniyki

xalqdin muloyim surud chiqarg‘ay... ‘A skilled singer

extracts a melody from the nation…’ (MQ 35).

3 CONCLUSION

The text corrected in British English is as follows:

Although the language of Alisher Navoi's works,

particularly the syntax of his prose, forms the

foundation for the syntax of modern Uzbek literary

language, the complexity of its syntactic structure, the

practice of composing distinctive phrases, and the

peculiar use of Arabic and Persian phrases set its

syntactic features apart from both related and

unrelated languages, as well as the contemporary

Uzbek language. Specifically, the new function of the

formant -ki//kim in the subject's composition is

becoming known in Alisher Navoi's prose. We hope

that these characteristics of Alisher Navoi's language

will enrich the content of the historical syntax of the

Uzbek language and attract the attention of foreign

linguists.

REFERENCES

Abdullaev F. (1974)How are words connected? -Tashkent:

Science,.

Abdullaev F., (1982) Ibrahimova F. Management in Uzbek.

- Tashkent: Science,.

Abdullaev F., Yusupov M. (1981)Some issues of the use of

Persian-Tajik and Arabic additions in the old Uzbek

language // Uzbek language and literature, , -№1.

Abdurahmanov G., Sulaymanov A., Kholyirov H.,

Omonturdiev J. ,(1979)Modern Uzbek literary

language. - Tashkent: Okituchi.

Ashirboev S. (1990) Structural and semantic features of

simple sentences in Alisher Navoi's prose works:

Philol. doctor of sciences ... dissertation. -Tashkent,.

Babayseva, V.V., Maksimov L.Yu. (1981) Contemporary

Russian language. Syntax, punctuation. - Moscow:

Prosvesheniya,.

Beloshapkova V. A., Zamskaya Ye. A., Milovslavskyi

N.G., Panov M.V. (1981) Modern Russian language. -

Moscow: Visshaya school,.

Bashmanov. M. (1982) Determinant clauses in the Uzbek

language // Uzbek language and literature. - Tashkent, ,

#2.

Vinogradov V.V. (1975) Osnovnie voprosi syntaxa

predlogeniya // Issledovaniya po russkoy grammatike. -

Moscow: Nauka,.

Omonturdiev J. (1980) Common participle, turn, adverbial

clause and their criteria // Grammatical construction of

the Uzbek language. - Tashkent: TDPU, ,

Omonturdiev J. (1988)The problem of using the term in

relation to the structural types of speech fragments //

Lexical-grammatical features of the Uzbek language. -

Tashkent: TDPU,.

Shoazizov Sh. Sh. (1973) Podlejashee i yego viragenia v

sovremennom uzbekskom literaturnom yazike:

Autoref. diss. ... kand.philol. science - Tashkent,.

Grammar of the Uzbek language. Syntax. - Tashkent.

Science, (1976).

Ghulomov A. G. (1955) It's simple. - Tashkent: FA

publishing house,.

Ghulomov A.G., Askarova M.A. (1965) Modern Uzbek

literary language. - Tashkent: Teacher,.

Hayitmetov K. (1981) Determinants in the aspect of the

theory of actual division of the sentence // Uzbek

language and literature, , -#2.

Hojiev A., Mahmudov N. (1983) Semantics and syntactic

position // Uzbek language and literature. - Tashkent, ,

- No. 2.

Modern Uzbek literary language. Syntax. - Tashkent:

Science,(1966).

ML – Alisher Navoi. (1941) Discussion dictionary: M.

Katrmere edition. - Paris,.

MN – Alisher Navoi. (1961) Majolisun Nafais: Scientific

and critical text // Prepared by S. Ganieva. Tashkent,.

MSh - Alisher Navoi. Source: Culliyot // National Library

of Paris (photocopy).

MQ – Alisher Navoi. (1948) Mahbubul kulub: Svodny

tekst podgotovil A. N. Kononov. -M. - L.: Iz-vo AN

SSSR,.

NM – Alisher Navoi. Nasoimul Muhabbat: Kulliyat //

National Library of Paris (photocopy).

HM – Alisher Navoi. Khamsatul mutahayyirin: Kulliyat //

Paris National Library (photocopy).

TMA – Alisher Navoi. (1975)History of Muluki Ajam:

Scientific text // prepared by L. Khalilov. - Tashkent,.

HPM - Alisher Navoi. Holoti Pahlovon Muhammad:

Kulliyat // Paris National Library (photocopy).

PAMIR 2023 - The First Pamir Transboundary Conference for Sustainable Societies- | PAMIR

220