EFFECTIVE XML REPRESENTATION FOR SPOKEN

LANGUAGE IN ORGANISATIONS

Rodney J. Clarke, Philip C. Windridge, Dali Dong

Faculty of Computing, Engineering and Technology, Staffordshire University, Beaconside, Stafford, United Kingdom

Keywords: XML, Spoken Language, CHAT, Transcription, Organisations

Abstract: Spoken Language can be used to provide insights into organisational processes, unfortunately transcription

and coding stages are very time consuming and expensive. The concept of partial transcription and coding is

proposed in which spoken language is indexed prior to any subsequent processing. The functional linguistic

theory of texture is used to describe the effects of partial transcription on observational records. The

standard used to encode transcript context and metadata is called CHAT, but a previous XML schema

developed to implement it contains design assumptions that make it difficult to support partial transcription

for example. This paper describes a more effective XML schema that overcomes many of these problems

and is intended for use in applications that support the rapid development of spoken language deliverables.

1 SIGNIFICANCE OF SPOKEN

LANGUAGE RESOURCES

Spoken Language is a central but nonetheless often

overlooked organisational resource. Its complexity

signals its enormous potential for a variety of

organisational applications including but not limited

to the analysis of decision-making processes;

negotiations occurring during the introduction of

new work practices into work places; training and

deployment of methods; and systems analysis,

design, development, installation, operation and

decommissioning. The complexity of spoken

language can be studied using a variety of research

approaches including various kinds of qualitative

analysis, contextual analysis, ethnography,

semiotics, and linguistics. As spoken language is

used to represent different kinds of meanings than

written language, this will necessitate special

technologies for its potential to be fully appreciated

and used.

A major operational difficulty that affects the

acceptance and uptake of approaches that utilise

spoken language resources to study organisations

and their associated technologies is the performance

bottleneck associated with the transcription and

coding processes. In part this is a consequence of

some basic assumptions about what constitutes

adequate spoken language data from a research

perspective. The belief that transcripts can only be of

use when they completely cover the entire

observational record and are exhaustive in terms of

coding is referred to here as a monolithic view of

transcription and its deliverables. As transcripts can

be re-analysed or reused for different purposes, the

notion that coding in particular can ever be complete

is questionable. Furthermore, due consideration must

be given to issues of security, privacy,

confidentiality and intellectual property related to

spoken language in organisational settings. It must

also be acknowledged that organisations constitute

‘unsafe environments’ for participants (Cameron et

al, 1992) involving issues of access, control, power

and representation. Therefore, the assumptions that

inform a monolithic view of transcription and coding

deliverables may need to be revised. In the following

section we propose moving from a monolithic to a

‘partial’ view of transcription and coding, and

suggest theory and methods that can assist us in

understanding the consequences of doing so.

2 CONCEPT OF PARTIAL

TRANSCRIPTION

One obvious strategy for dealing with the

bottlenecks and problems associated with

transcription and coding processes in organisational

settings is to omit chunks of the observational record

based on the occurrence of an explicit indexing

486

J. Clarke R., C. Windridge P. and Dong D. (2004).

EFFECTIVE XML REPRESENTATION FOR SPOKEN LANGUAGE IN ORGANISATIONS.

In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Enter prise Information Systems, pages 486-491

DOI: 10.5220/0002601604860491

Copyright

c

SciTePress

phase prior to transcription and coding itself. In

contrast to a monolithic approach to transcription,

previously described, the production of intentionally

incomplete transcription and coding deliverables is

referred to here as partial transcription. The

advantages of partial transcription include amongst

other things the ability to encourage empowerment

research (see Cameron et al, 1992) by enabling the

participants themselves to determine what gets

recorded. This facilitates trust and improves the

research relationship between analysts and members

of organisations. An obvious difficulty with partial

transcription is that, depending on the kind of

analysis being undertaken, omitting sections of a

transcript will disrupt a number of spoken language

resources- some of these may be crucial to the

analysis being conducted. Fortunately, functional

linguistic theories exist which can give considerable

insight into which specific language resources will

be affected. We use Systemic Functional Linguistics

(SFL) a semiotic model of language (Halliday,

1985) because it has a concept referred to as texture

that encompasses and defines all the text-forming

resources that may be used in a transcript or any

other text. For example, texture has also been

applied to hypertext development and modeling

(Clarke, 1997). Any texts including all transcripts

must possess texture in order to function as a

semantic unit, as well as being relevant or

appropriate to a given social setting or occasion.

Whether knowingly or not, speakers and writers use

their experience of texture resources when

constructing texts, while listeners and readers use

their experience of these resources when interpreting

texts. Texts are generally read from start to finish

and so many of these resources flow through a text

in chains. This is an attribute of language referred to

as sequential implicativeness (Schegloff and Sachs,

1973). For example a text might start with the

sentence “Rod is in the Red Theatre” and if the next

sentence was “He is giving a seminar” we might

reasonably conclude that the ‘He’ is Rod. This is an

effect of sequential implicativeness in the so-called

Reference System (see below).

There are several models of texture within SFL.

The texture model we use (Martins’ 1992, 381

adaptation of Halliday and Hasan’s 1976 model)

recognises three major groups of text-forming

resources- Intrasentential Resources, Intersentential

Resources, and Coherence. Within each major

group, there are a number of sub-categories of text-

forming resources each having an associated

analysis method and some also have graphical

methods:

– intra-sentential resources (Martin 1992, 381) or

structural resources (Halliday, 1985)- involve

systems of THEME and INFORMATION and

spoken language specific systems involved in

Conversation Structure. All texts consist of sets

of clauses each of which can be divided into a

theme and a rheme. Listeners or readers rely

upon thematic progression, the specific pattern

of themes, to predict how the text should unfold.

Texts must also provide and ‘manage’

information. Listeners or readers come to rely

upon patterns of information units to build and

accumulate new meanings from those that have

already been given. Conversation Structure

involves speech functions the characteristic set

of moves enacted by participants involving

initiations (offers, commands, statements,

questions) or responses, as well as sequences of

speech functions that form jointly negotiated

patterns called exchange structure.

– intersentential text-forming resources of

Cohesion- describe how clauses within any text

are interrelated giving the appearance of a unity

thereby assisting listeners and readers in

understanding the meanings being negotiated.

There are a number of types of cohesion,

including lexical cohesion which describes how

lexical items (words) and sequences of events

are used to consistently relate a text to a topic,

reference which describes how participants are

introduced and subsequently managed, ellipsis

which establishes reference relationships through

the omission of otherwise repetitive lexical

items, substitution which employs alternate lexis

for original lexical items, and conjunction which

refers to the logical relations between parts of a

text.

– text forming resources of Coherence- which

describes how clauses in texts relate to the

contexts in which they occur. All texts must be

relevant to the immediate situational context,

referred to as situational coherence, while also

conforming to an appropriate genre, referred to

as generic coherence.

It is relatively easy to understand in principle

what happens when we partially transcribe.

Effectively we run the risk of disrupting sequential

implicativeness of many of these text-forming

resources. Partial transcripts may loose coherence,

and will most certainly have disrupted thematic and

informational intra-sentential resources. Perhaps the

group of text forming resources most disrupted will

be cohesion as omitting clauses make it more

difficult for readers to understand the transcript as a

unity. We could easily produce an unintelligible

partial transcript if we removed too much of it.

While texture theory can tell us which language

resources will be affected when we adopt partial

transcription, it can only provide part of the picture.

The theory of texture cannot tell us how significant

EFFECTIVE XML REPRESENTATION FOR SPOKEN LANGUAGE IN ORGANISATIONS

487

the disruption will be for the type of research

methodology being undertaken. NLP analyses may

find partial transcription useful because redundancy

within and interdependency between text-forming

resources can offset the fact that the transcript is not

complete. We might expect qualitative analyses to

be adversely affected by partial transcription

although this may be almost completely offset by

carefully designing the indexing phase. The indexing

phase may function to provide Code Tables for those

qualitative methodologies that use descriptive,

interpretative or pattern codes based on relatively

pre-established analytical categories (see Miles and

Huberman 1994, 57-72). However, grounded theory

and ethnographic methodologies are more likely to

be adversely effected by adopting partial

transcription. Of course, it is impossible here to

consider all the ways in which a text may have its

texture forming resources affected by partial

transcription, but knowledge of these resources can

help us greatly. Having established partial

transcription as a potentially useful approach to

dealing with the bottlenecks associated with

transcription and coding processes in organisation it

became a mandatory requirement in our studies. We

now turn our attention to ways in which we

represent the transcript content and metadata.

3 REPRESENTING TALK: CHAT

AND THE TALKBANK SCHEMA

Even in the research literature, transcription is often

ad hoc and idiosyncratic; formal standards are not

necessarily well known. One of the best-defined

transcription standards is CHAT- Codes for the

Human Analysis of Transcripts developed by Brian

MacWhinney and Jane Walter at the CHILDES-

Child Language Data Exchange Research Centre,

Department of Psychology, Carnegie Mellon

University (CHILDES, 2003). CHAT is a scalable,

elaborate and expressive standard that supports

transcription and coding even under the most

adverse of conditions (participants with speech

impediments, unclear or noisy recordings, breaks in

the observational record). The standard is extensible,

providing a consistent way of adding new headers if

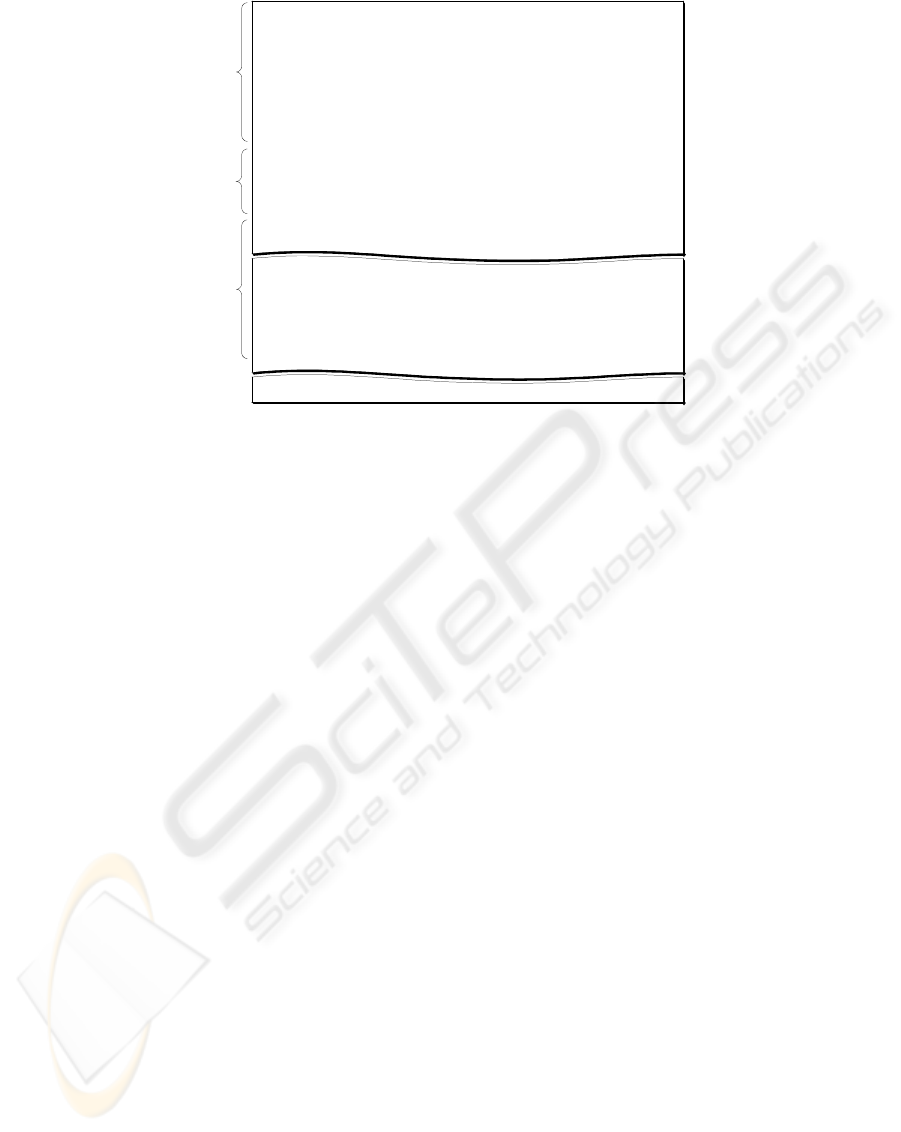

necessary (MacWhinney, 2003). As illustrated in

Figure 1, CHAT transcripts have a common basic

structure. A block of so-called Constant Headers at

the top of the transcript starting with an @Begin

provides persistent information, which is applicable

throughout the transcript. Some headers can occur

more than once in a transcript signalling for

example, changes in situation, space and time, and

are referred to as Changeable Headers. The body of

the transcript consists of speaker utterances called

Mainlines, signalled with an asterix and a three-

letter participant code. Each mainline may be

followed by zero or more Dependent Tiers, used for

coding information about the utterances. These start

with a percent sign and three-letter code that

@Begin

@Participants: CAR Caroline Adult, DAL Dali Adult, PHI Phil Adult

@Age of CAR: 40;

@Sex of CAR: female

@SES of CAR: working

@Age of DAL: 29;

@Sex of DAL: male

@SES of DAL: working

@Age of PHI: 34;

@Sex of PHI: male

@SES of PHI: working

@Coder: Phil Windridge

@Transcriber: Phil Windridge

@Date: 20-FEB-2003

@Filename: SL6

@Time Duration: 10:00-10:46

@Room Layout: K316; several tables pushed together in the centre of the room leaving little room to squeeze

around the outside; whiteboard, OHP and a bookcase full of PhD and Masters dissertations

@Situation: Caroline, Dali and Phil conduct an informal technical meeting for SemLab

*DAL: yeah that's nice, ok.

%act: adjusts the mini disk equipment

*CAR: [=! chuckles] okay # right.

*DAL: <<so that's> [//] er actually <that's what I'm trying> [//] still trying working on it>[>].

*CAR: <mmhm>[<].

*DAL: probably, <I was> [/] I was searching the internet <for this information> [//] whether they got the information.

@End

Mainlines/

utterances

Constant

header

Constant

headers

Changeable

headers

Mainline

Dependent Tier

Figure 1: Structure of a simple CHAT Transcript. The special symbols in the mainlines indicate group

structure. The excerpt is from ‘SL6’, SemLab Corpora (after Clarke et al 2003).

ICEIS 2004 - INFORMATION SYSTEMS ANALYSIS AND SPECIFICATION

488

indicates the type of coding information provided.

The single command @End is used to mark the end

of the transcript.

One of the reasons that CHAT is of interest for

researchers of spoken language in organisational

settings is that it was developed with subsequent

computer processing in mind. A suite of programs

called CLAN can be used to parse CHAT compliant

transcripts. Development work has proceeded in

several directions under the aegis of a National

Science Foundation funded joint project between

Carnegie Mellon and Pennsylvania Universities

called TalkBank. The first direction involves

expanding the range of media used in the study of

communication. The second direction involves

leveraging the advantages afforded by XML and

related technologies. Within TalkBank, the spoken

language resources are represented using CHAT.

The design of the current TalkBank (2003) schema

appears to be based on creating an XML version of

the CHAT standard and for the most part appears to

reproduce the structure of a CHAT file itself. A

design assumption that informs the TalkBank

schema is that transcripts are monolithic entities, as

previously defined, and this reflects the kind of

applications that CHAT was developed to address.

As described in section 2, transcription in

organisational settings and for organisational

purposes necessitates a different design approach,

which we believe makes the adoption of the current

TalkBank CHAT schema problematic for the

following reasons:

– Monolithic View of Transcripts: Above the level

of the utterance, TalkBank views transcripts as

monolithic and non-hierarchical entities.

However in organisational settings, transcripts

may more usefully be considered otherwise and

this should be reflected in the XML used to

represent them. An appropriate XML schema for

these purposes would, for example, place

episodes at a higher level than utterances in the

XML hierarchy.

– Overloading of the Schema: A consequence of

modeling the design of the XML schema on the

CHAT file structure itself is that the resulting

single file becomes huge. If all analyses must be

contained within the one file then any schema

will become overloaded.

– Over-specification of CHAT semantics: The

TalkBank XML schema over-specifies certain

aspects of the CHAT syntax. For example the

use of an explicit pause element complicates the

schema by replacing one character with an entire

line while not contributing anything to the

CHAT semantics.

– Coupling between Schema and Standard: The

over-specification of the CHAT semantics,

described above, induces a very tight coupling

between the CHAT standard and its current

XML representation. This means that any

changes to the standard also require reworking of

the XML schema itself. This may create a

version control problem, likely to require

modification of the existing XML schema, XML

documents using this schema and associated

XSLTs.

– Poor Group Support: There are several kinds of

scoped symbols used in CHAT to show ranges

within utterances (MacWhinney, 2003). Of

particular interest in our applications are

paralinguistic scoping, the provision of

explanations or alternative realisations for what

was spoken, retracing by or overlapping between

speakers, or to signal the existence of errors.

Limitations in the TalkBank (2003a) schema

preclude the representation of overlapping group

structures, which are extremely important for

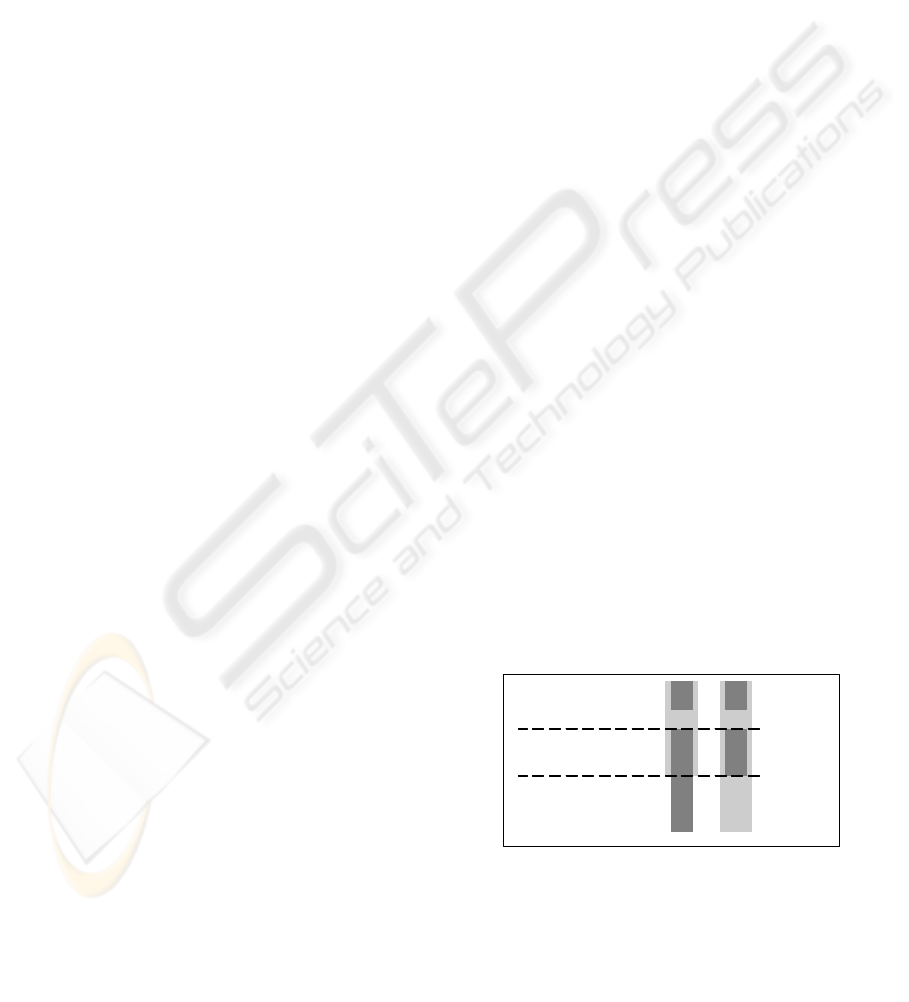

NLP applications. Figure 2 shows an XML

representation of an excerpt from SL6, part of the

SemLab Corpora (Clarke et al, 2003). The group

structure in the excerpt can be interpreted in two

entirely different ways. The region of ambiguity

can only be resolved with reference to the

original source material.

– Lack of Version Control: As with conventional

CHAT, the TalkBank schema does not enable

the content of a transcript to be version

controlled. In effect the only version of a

transcript is the current one. A lack of version

control is a significant problem for

organisational applications, which assume that

spoken language resources are not monolithic.

In order to support transcription and coding in

organisational settings, the current TalkBank schema

was abandoned and we developed an XML schema

called the Spoken Language Architecture. In order

to use this new schema we developed tools which

enable us to prepare, index, transcribe and code

<w><<so</w>

<w>th a t's > </w >

<w>[//]</w >

<w>er</w>

<w>actually</w >

<w><that's</w>

<w>what</w>

<w>I'm </w >

<w>trying></w >

<w>[//]</w >

<w>s till</w >

<w>try in g </w >

<w>working</w>

<w>on</w >

<w>it> </w >

<w>[> ]</w >

<w>. </w >

Am biguous

group

boundaries

<<so that's> [//] er actually <that's w hat I'm

try in g > [//] s till try in g w o rk in g o n it> [> ].

Figure 2: XML Representation of the excerpt from

‘SL6’, SemLab Corpora (after Clarke et al 2003). Two

entirely different interpretations of a group structure are

shown (the right hand side shows an embedded group). The

ambiguity between these interpretations affects the text

between the dashed lines.

EFFECTIVE XML REPRESENTATION FOR SPOKEN LANGUAGE IN ORGANISATIONS

489

transcripts. The following section describes our

XML representation for the Spoken Language

Architecture.

4 XML REPRESENTATION FOR

THE SPOKEN LANGUAGE

ARCHITECTURE

In order to develop the Spoken Language

Architecture for use in organisational settings, we

abandoned the design option of using a single XML

file to represent a transcript, in favour of a multi-file

XML schema. The resulting Spoken Language

Architecture consists of a Descriptor file comprising

most of the coding and indexing information that

may be supplied by other applications, and a Root

file that consists of utterances and the codes that are

immediately related to them, see Figure 3.

The SLA schema has the following attributes:

– Incremental Production of Transcripts: The

concept of partial transcription was described in

section 2. The multi-file XML schema is the

basis of the Spoken Language Architecture and

supports the incremental development of

transcripts- akin to developing ‘transcripts in

pieces’.

– Extensibility and Processing: The XML schemas

used in the Spoken Language Architecture are

designed to be as open as possible- as new

applications emerge for spoken language

resources, the XML schema can be expanded to

accommodate them by associating purpose

specific Descriptor files with the SLA Root file.

– Abstraction of CHAT Semantics: The Spoken

Language Architecture abstracts the CHAT

semantics in such a way as to reduce the need to

change the design of the XML when the syntax

of the CHAT standard changes. An example of

this is information related to participants in the

transcripts. Alterations to CHAT standard syntax

have resulted in the addition of an obligatory

@ID header to present information in a different

format. The abstraction of this information in the

SLA architecture would allow reformatting to

whatever syntax was applicable in a given

version.

– Partially or Completely Overlapping Regions:

Correctly identifying groups adds semantic

information to the transcript. However group

boundaries are not easily defined because the

group structures used in CHAT can remain

ambiguous without reference back to the original

source material. In XML it is only possible to

represent groups of words in the transcript where

they are embedded in, or isolated from, other

groups. To overcome this constraint it is

necessary to separate group structure from group

content. Consequently, groups can be

represented as isolated, embedded or

overlapping. Embedded and overlapping groups

are especially important in natural language

processing applications.

– Version Control for Transcripts: A requirement

necessitated by the use of partial transcription is

the need to modify embellish, update improve)

the transcript over time. Not only is it necessary

to keep track of these modifications it is also

useful too have the ability to reverse the effect of

these changes. In SLA, the version control of

transcripts is handled by the addition of Changes

files to record updates and inserts on both the

SLA Root and Descriptor files.

A fully CHAT compliant transcript could be

rendered either by using an XSLT in conjunction

with a helper application or by using purpose-built

applications that would process the SLA XML

schema directly. The latter approach is more

interesting as different bespoke and third party

applications could in principle contribute to the

creation and management of data streams that would

be registered and consolidated together to form

various transcription and coding deliverables.

5 CONCLUSIONS AND FURTHER

RESEARCH

Spoken language is a valuable yet often

underutilised resource in organisational settings. The

major bottlenecks involved in utilising these

resources in the study of organisations are the

crucial stages of transcription and coding. These

stages are time-consuming and the assumption that

Figure 3: Relating the SLA Descriptor file to word

group ranges in the Root file.

ICEIS 2004 - INFORMATION SYSTEMS ANALYSIS AND SPECIFICATION

490

spoken language records need to be completely

transcribed and coded reduces the likelihood that

these resources will be utilised. If we first index the

observational record then we can drastically reduce

the amount of effort and cost of pre-processing

spoken language resources by identifying only those

parts of the record that need to be transcribed and

coded. We applied the concept of texture from

Systemic Functional Linguistics to describe and

account for the effect of partial transcription on the

observational record. In general, it is the text-

forming resources of cohesion that are particularly

sensitive to the omission of clauses and

consequently this makes the resulting transcript

more difficult for readers to understand as a unity.

We could easily produce an unintelligible partial

transcript if we did not transcribe and code enough,

so knowledge of these resources provides an

important theoretical underpinning to partial

transcription.

One of the best transcription and coding

standards is the CHAT transcription system. A

critical evaluation of the TalkBank XML schema for

CHAT revealed that it could not satisfy the design

requirements for the spoken language architecture in

organisational settings. We therefore developed a

new multi-file XML schema called Spoken

Language Architecture (SLA) to support CHAT

while allowing transcripts to be incrementally

developed, enabling us to move away from treating

transcripts as monolithic units. Extensibility of the

SLA schema and abstraction of the CHAT semantics

address the issues of schema overloading, over-

specification of the CHAT semantics and coupling

between the schema and standard evident in

previous approaches. Having argued the need for

version control in organisational applications, the

relative ease with which version control was

incorporated into SLA demonstrates the

appropriateness of an extensible multi-file XML

schema for spoken language resources.

Future work will be involved in applying the

theory of texture to account for the effects that text-

forming resources will have on transcripts at various

stages of completion. It is hoped that visualization

tools can be developed that will enable the mutual

interaction between these text-forming resources to

become easier to understand and estimate. Tools that

support the production of ‘transcripts in pieces’ are

currently under development .

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research presented here was partially funded

through two United Kingdom Engineering and

Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC)

grants, Semiotic Enterprise Design for IT

Applications (SEDITA) jointly conducted by

Staffordshire and Reading Universities, Grant

Reference: GR/S04833/01, and Reducing Rework

Through Decision Management (TRACKER) jointly

conducted by Lancaster and Staffordshire

Universities, Grant Reference: GR/R12176/01.

REFERENCES

Cameron, D.; Frazer, E.; Harvey, P.; Rampton, M. B. H.

and K. Richardson, 1992. Researching Language:

Issues of Power and Methods Chapter 1:

“Introduction”, London and New York: Routledge 1-

28

CHILDES, 2003. Child Language Data Exchange System

http://childes.psy.cmu.edu/

21 August

Clarke, Rodney J., 1997. “Texture during Hypertext

Development: Evaluating Systemic Semiotic Text-

Forming Resources” in SEMIOTICS’97: 1st

International Workshop on Computational Semiotics

May 26-27, 1997, Leonard de Vinci Pôle

Universitaire: The International Institute of

Multimedia, Paris La Defense Cedex, France

Clarke, Rodney J.; Chibelushi, Caroline; Dong, Dali and

Phillip C. Windridge, 2003. SemLab Systems

Development Corpora, Faculty of Computing,

Engineering and Technology, Staffordshire

University, United Kingdom

Halliday, Michael A. K., 1985. An Introduction to

Functional Grammar London: Edward Arnold

Halliday, Michael A. K. and Ruqaiya Hasan, 1976.

Cohesion in English London: Longman

MacWhinney, Brian, 2003. CHAT Transcription System

Manual

http://childes.psy.cmu.edu/manuals/CHAT.pdf

Martin, James R., 1992. English Text: System and

Structure Amsterdam: John Benjamins

Miles, Matthew B. and A. Michael Huberman, 1994.

Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook

Second Edition Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications

Schegloff, E. A. and H. Sachs, 1973. “Opening up

Closing” Semiotica 7 (4), 289-327

TalkBank, 2003. XML Schema version 1.1.3

http://xml.talkbank.org:8888/talkbank/talkbank.html

EFFECTIVE XML REPRESENTATION FOR SPOKEN LANGUAGE IN ORGANISATIONS

491