STRATEGIC ANALYSIS OF THE ENVIRONMENT

A DSS FOR ASSESSING TECHNOLOGY ENVIRONMENTS

Giovanni Camponovo, Samuel Bendahan, Yves Pigneur

University of Lausanne, Switzerland

Keywords: Decision support system, environmental scanning, strategy alignment

Abstract: Assessing the external environment is an important component of organizations' survival and success.

Unfortunately, a huge amount of information must be collected and processed in order to obtain a thorough

and comprehensive representation of the environment. A decision support system can be very useful in

helping decision makers to organize and analyze this information efficiently and effectively. This paper

outlines a conceptual proposition helping to design such a system by presenting an ontology of the relevant

information elements (actors, issues and needs) and a set of tools to analyze them. This paper also illustrates

a prototype version of one of these tools which supports the analysis of the actors and issues perspectives.

1 INTRODUCTION

Assessing the environment of an organization can be

defined as a search for information about events and

relationships in a company's outside environment,

the knowledge of which can help its top

management to plan the company's future course of

action (Aguilar 1967). Organizations scan their

environment in order to understand the external

forces of change that may affect their future position

so that they can develop effective responses.

Researches from different disciplines recognize

that understanding their own environments and

consequently adapting their strategies to it is highly

important to the organizations' survival and success.

From a systems theory perspective, companies

are seen as complex social open systems (Boulding

1956), which are involved in a variety of exchanges

with a larger system which is globally referred to as

their environment. These exchanges are considered

of primary importance as they are the source of the

input resources required by the organization and the

destination of its output (Katz and Kahn 1966).

The importance of obtaining a thorough

perception of the environment has also been

acknowledged by numerous prominent authors in

strategic management, as shown in the following

paragraphs. In particular, the alignment between the

organization’s strategy and its environment is seen

as essential for performance.

Indeed, one of the fundamental models that lies

at the core of modern strategic management, the so-

called Harvard normative model, makes its essential

contribution by stating that organizations must craft

their strategies based upon the prior identification of

the present and future opportunities and threats in

the environment and the match between these and

the organization's unique strengths and weaknesses

stemming from corporate resources and

competencies (Learned, Christensen et al. 1965).

Many other renowned researchers are proponents

of theories supporting the importance of monitoring

the environment and achieving alignment with

organizational strategy, structure, and performance

(Dill 1958; Bourgeois 1980; Andrews 1987). Some

further advise firms to proactively influence their

environment to attain more favorable conditions

(Porter 1980; Godet 2001).

Additional support can be found in the disruptive

technologies literature. It suggests that established

firms often fail to cope with a changing environment

due to their focus on current customers. This hinders

them from perceiving and dealing with change that

does not initially affect their mainstream market but

can later disrupt it (Christensen and Bower 1996).

A few empirical studies support the importance

of environmental scanning and suggest a positive

relationship with organizational performance (Choo

2001). For instance it has been found that higher-

performing firms are characterized by more frequent

scanning and by more careful tailoring of scanning

122

Camponovo G., Bendahan S. and Pigneur Y. (2004).

STRATEGIC ANALYSIS OF THE ENVIRONMENT A DSS FOR ASSESSING TECHNOLOGY ENVIRONMENTS.

In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, pages 122-129

DOI: 10.5220/0002614401220129

Copyright

c

SciTePress

to perceived strategic uncertainty (Daft, Sormunen et

al. 1988) and that firms having advanced

environment monitoring systems exhibited higher

growth and profitability than firms that did not have

such systems (Subramanian, Fernandes et al. 1993).

Research has shown that environmental analysis

becomes even more essential in industries which are

characterized by disruptive, uncertain and complex

environments. These are commonly considered as

the major drivers of environmental scanning (Daft,

Sormunen et al. 1988; Boyd and Fulk 1996).

Ironically, these characteristics that increase the

value of scanning also make it more difficult and

costly. Such environments usually characterize

technologically intensive industries such as the

mobile business, e-business and software industries.

Unfortunately, while the development of

knowledge has produced many techniques to deal

with parts of the problem, there is no easy

methodology allowing for a systematic assessment

of the environment (Andrews 1987, p. 39).

Moreover, due to the huge amount of information to

be collected and processed, decision makers should

be assisted by decision support systems providing

them the tools to systematically take advantage of

the information at their disposal (Aguilar 1967).

The main objective of this paper is to provide

conceptual foundations which aim to facilitate the

development of an environmental decision support

system. In particular, the paper provides an ontology

indicating the relevant elements to monitor and their

relationships. This ontology, presented in section 2,

provides insights on how to structure the collected

information. In addition, the paper provides a set of

complementary analytic and visualization tools (see

section 3) which allow users to analyze this

information from different perspectives, thus

providing a complete image of the environment.

A prototype tool is presented in section 4 in

order to give a preliminary idea of the usefulness of

an environmental DSS. At the time of writing, this

tool integrates only a subset of the proposed

elements, but it will be extended in future work.

2 ENVIRONMENT ONTOLOGY

This section presents a conceptual framework

intended to facilitate the collection and organization

of the relevant information by indicating the

elements to monitor and their relationships.

Although the relevant elements to observe

essentially depend on the specific context under

study, it is possible to describe a set of sufficiently

abstract elements that should be assessed in any

environment analysis. In a concrete case, these

elements can be instantiated so as to match the

particularities of the context under study.

In order to identify these elements, the literature

was reviewed to identify and compare the elements

proposed by the various existing approaches. In fact,

there is a variety of complementary approaches

which are focused on different environmental

dimensions and have different scopes such as the

competitor, competitive, business, technology and

market intelligence, environment scanning, actors-

issues models etc. (Choo 1999).

From the analysis of these approaches, three

elements show up as highly relevant: the market, the

actors and the issues. The market is the key element

proposed by the business and market intelligence,

but is at least mentioned by all other approaches.

Analysis of the actors is advised by actor-issues

methods, competitor, competitive and business

intelligence. Finally, issues are the key proposal of

actor-issues methods and environmental scanning.

These elements are intertwined by a series of

influence relationships as depicted in Figure 1

The market or use perspective represents the

demand side of the organization's environment.

According to Kotler (Kotler 2003, p. 11), assessing

the market basically implies investigating the end

user needs and how they are translated into wants

(desires to buy specific products to satisfy these

needs) and demands (capacity and willingness to pay

for these products). It is also important to understand

how customers value the various elements of the

value propositions (a sets of benefits embodied in a

combination of products and services that satisfies

certain needs) and choose the solution to adopt.

Research in marketing has shown that the market

is not a homogeneous group, but that buyers tend to

have individual needs, behaviors and preferences. A

process of segmentation is commonly used to

identify "groups of customers that have similarities

in characteristics or needs that are likely to exhibit

similar purchase behavior" (Smith 1956). It is vital

to gather information about the customers (i.e. in

terms of socio-demographic, psychographic and

ACTORS

MARKET

ISSUES

Influence

Influence

Influence

Influence

Influence

Influence

Figure 1: environmental ontology

STRATEGIC ANALYSIS OF THE ENVIRONMENT: A DSS FOR ASSESSING TECHNOLOGY ENVIRONMENTS

123

behavioral variables) that compose each segment.

Knowledge of customers' needs, wants, demands

and segments allows firms to conceive more

attractive value propositions and to gain substantial

competitive advantage. Actually, some firms try to

integrate their customers in the value proposition

design (i.e. through mass customization).

The actors perspective represents the supply side

of the environment. The relevant actors are those

that have the power of directly or indirectly

influence the organization's performance.

Among these actors, a prominent place is taken

by the different players that contribute to satisfy the

same end-user needs. As illustrated by Porter (Porter

1980), these players principally include not only the

organization's existing direct competitors, but also

the players in adjacent industries along the value

system such as suppliers, distributors, new entrants

and substitute product producers.

However, other influential players in diverse

environmental areas must be taken into account. It is

indeed suggested to consider all the actors which can

influence the evolution of the environment (Godet

2001). In particular, it is worth considering players

in the less immediate environment such as

regulatory authorities and technology suppliers.

Finally, issues can be defined as open and

debatable questions, events or other forthcoming

developments whose realization can significantly

influence the future conditions of the environment

and, consequently, the ability of the organization to

achieve its objectives (Ansoff 1980). Issues can arise

in different environmental areas such as the market,

technology, regulatory, economic and social areas.

Issues are an important element of environmental

analysis. While the two other elements provide a

good picture of the current conditions, they are not a

sufficient basis for guiding decisions which deploy

their effect in a relatively distant future. In changing

environments, companies must continually look

beyond the current environmental state and assess its

future prospects. Due to the high uncertainty of

future developments, this often leads to establishing

a number of scenarios rather than a single forecast.

In this respect, issues are a good mechanism to

reflect on possible disruption of current conditions

and trends, allowing the development of a broader

set of scenarios. Particularly interesting issues are

those that are open to dispute and upon which actors

have diverging positions and means of influence.

Notice that these elements are consistent with the

observations of Porter, which asserts that industries

with rapidly changing and complex environments

experience significant uncertainties about demand,

strategy and technology (Porter 1980). The proposed

elements cover the mentioned uncertainties: the

market deals with demand uncertainties, actors cope

with supply and its related strategic uncertainties,

and issues cover environmental factors which

include technology (Camponovo and Pigneur 2003).

These elements are inextricably intertwined and

interact through influence relationships. While this

concept is generic, relationships between a particular

pairs of elements have an adapted meaning.

The market and actors are linked by a market

relationship: by adopting certain value propositions

as an expression of their needs, end users influence

the type of products that are offered by the different

actors and hence determine their relative power;

conversely actors can often shape and even create

user needs by offering innovative value propositions.

Market and issues are linked by an adoption

relationship in the sense that the realization of issues

can affect end user needs and, consequently, the

solutions they adopt. Conversely, the adoption of

certain solutions may affect positively or negatively

the probabilities of realization of certain issues.

Actors and issues are linked by a position

relationship. Actors can influence the realization of

certain issues by strategically positioning themselves

on them. On the other hand, the realization of issues

constrains the strategic possibilities open to actors.

Finally influence relationships also exist between

the instances of issues, actors and needs. Actors are

linked by pressure relationships (Porter 1980), issues

by dependency relationships (Arcade, Godet et al.

1999) and needs by a contribution relationships.

These relationships can create a complex

network of indirect relationships between elements.

For instance, the pressure relationships between

actors can potentially change as a result of the

realization of certain issues or shifts in user needs.

3 ANALYSIS TOOLS

This section presents a selection of methods and

tools to collect analyze and visualize information

about the different elements of the previous section.

Before illustrating these methods, it is useful to

remind that there is a wide variety of information

sources that may convey useful information. They

have been categorized by the internal vs. external,

personal vs. impersonal and verbal vs. written

dimensions (El Sawy 1985). For instance, personal

sources include external actors (i.e. competitors,

customers, experts, suppliers, consultants etc.) as

well as internal employees, staff and managers at all

levels. Impersonal sources include internal reports

and enterprise information systems, as well as

external publications such as trade journals, research

reports, the mass media and online sources (El Sawy

1985; Choo 1994).

ICEIS 2004 - ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND DECISION SUPPORT SYSTEMS

124

3.1 Market

A good starting point in analyzing the market

perspective is to exploit the wealth of internally

available information. In fact, through customer

interaction, an organization knows a lot about its

market. In addition to the opinions of the various

employees (e.g. sales force, staff, managers,...),

enterprises commonly have sophisticate internal

record systems (e.g. transaction histories, sales

reports, customers databases) which can be exploited

through a variety of data mining techniques. Seldom,

companies also possess market intelligence systems

and internal market research departments.

It is imperative to complement this internal point

of view on the market with external information in

order to avoid overemphasizing current visions,

beliefs and assumptions about the market.

External secondary data consist in market

reports, various business, governmental or academic

studies and publications and published statistics

(demographics, economics, industry...). This data

has a lower cost and is readily available and should

therefore be used first.

Primary data should then be used to gather

complementary information and get fresh insight

into original aspects of the market. Many research

instruments can be used to collect primary data.

The traditional way of investigating end user

needs is by directly asking users to elicit their needs.

There is a variety of quantitative and qualitative

methods including surveys, interviews, customer

visits and focus groups (McQuarrie 1996). Alas,

they are better suited for descriptive research than to

discover actual user needs. Reasons are that users

are hardly conscious of their real needs and are

prone to reporting bias.

An alternative consists in focusing on the user's

behavior. There is a multitude of methodologies

from different research disciplines such as diffusion

studies (studying the link between the characteristics

of an innovation and its diffusion process), adoption

studies (focusing on the individual user's decision to

adopt a particular service), uses and gratification

studies (studying the gratifications sought in

adopting a new service), domestication studies

(studying the societal consequence of domestication

of everyday life technology), observational research

(ethnography, participant, indirect observation,

usability studies) and experimental methodologies

(e.g. simulated shopping experience in a controlled

environment) (Pedersen and Ling 2002; 2003).

Companies must also understand the possible

market evolution. There is a multitude of forecasting

methods, such as various extrapolation techniques,

probabilistic forecast, scenarios, expert opinion,

delphi, buyers' intentions survey,... (Martino 2003).

An interesting approach is to assess the

disruptiveness of emerging value propositions by

comparing them to the ordinary ones on a number of

dimensions (Rafii and Kampas 2002).

3.2 Actors

Understanding the roles of the different actors

participating in a business system is essential

because of their central role in shaping the future

environment state by partly influencing some of the

forces that govern its evolution.

For assessing the role of the key players, it is

recommended to briefly but clearly describe their

business models. This essentially implies describing

the organization's value proposition, its target

customers, its infrastructure (activities and

partnership network) and its financial aspects

(Osterwalder and Pigneur 2002).

Based on the business model of the different

actors, it is also possible to assess the relationships

and interactions among them. The well-known value

chain framework (Porter and Millar 1985), which

defines the value system as composed by a series of

interconnected value-adding activities performed by

the various enterprises along the supply chain, can

be seen as the integration of the participants’

business models. While this framework is adapted to

manufacturing, there are extensions suited to service

providers and brokering activities (Stabell and

Fjeldstad 1998).

While these methods enable us to assess the

relations between entities stemming from exchanges

of value, there are important indirect relationships

between actors that must be taken into account, too.

These have been brilliantly illustrated by Michael

Porter’s five-forces framework (Porter 1980), which

advocates the important effect on the firm by the

pressure of existing competitors, suppliers, buyers,

new entrants and substitute products producers. This

framework can be extended to include other

categories of players in the regulation (Rugman and

Verbeke 2000) and technology areas.

3.3 Issues

Since the main goal of environment analysis is to

anticipate the potential changes that occur in it, it is

argued that the company must look beyond the

current market state and assess the most important

future prospects of its environment. This can be

done by identifying and assessing the major issues

and trends that may affect the environment.

While trends indicate the most likely evolution,

issues determine possible departures from these

STRATEGIC ANALYSIS OF THE ENVIRONMENT: A DSS FOR ASSESSING TECHNOLOGY ENVIRONMENTS

125

trends towards alternative futures. Both elements

must be obviously considered. Issues can be seen as

forthcoming developments which are likely to have

an important impact on the ability of the

organization to achieve its objectives (Ansoff 1980).

Identification of the relevant issues is a difficult

task and is mostly a matter of judgment. It often

must rely on the opinion of a group of experts. A

number of methods can help by fostering creativity

(e.g. brainstorming, assumption reversal, and

analogies), consensus (e.g. delphi, nominal groups)

and collaboration (e.g. group support systems).

Godet proposes a systematic method for

identifying, classifying and prioritizing issues. This

method, called MICMAC, is based on the concept of

influence and dependence between issues and

classifies issues as dominant, relay, dominated and

autonomous (Arcade, Godet et al. 1999).

An interesting category of tools are actor-issues

methods. These basically consider the environment

as a game between multiple actors that try to

influence the factors (i.e. the issues) that govern its

evolution either by mobilizing their resources to

influence the issues outcome directly or indirectly by

influencing (i.e. negotiating with) other actors.

There are a few actor-issue methods which stem

from various disciplines and provide different

information. The MACTOR method (Arcade, Godet

et al. 1999) originates from a systemic perspective

and provides an aggregate overview of the system

under study through a number of computations on

several input matrices. Allas and Georgiades (Allas

and Georgiades 2001) developed a simpler model to

support negotiators, which essentially consists in a

set of graphs that provide strategic information.

Other methods tackle the same problem based on

game theory using expected utility calculations

(Bueno de Mesquita and Stokman 1994).

4 A PROTOTYPE: MASAM

Based on the previous considerations, we conceived

a prototype tool called MASAM based on previous

actor-issues methods so as to integrate the actor and

issue perspectives. It provides a preliminary insight

on the usefulness of a more elaborate system. This

prototype will be extended in forthcoming work to

include the market perspective. In the meantime, this

perspective can be regarded as a particular case of

issues (e.g. social, demographic and economic issues

affecting user needs, wants and demand) and actors

(customers, consumer groups).

MASAM is a tool based on the multi actor-issue

models proposed by Godet (Arcade, Godet et al.

1999) and Allas (Allas and Georgiades 2001).

Actually, it integrates both models, corrects some of

their flaws and adds new features as described in

(Bendahan, Camponovo et al. 2003).

This tool is intended to assist decision makers in

analyzing situations involving multiple actors that

have divergent interests on multiple issues. It helps

them to devise a suitable strategy which takes into

account the interests and potential actions of other

actors as well as the potential disruptive effects of

the realization of certain issues on the environment.

In particular, it can be used to support the selection

of multiparty negotiation strategies or as part of a

more ambitious scenario planning approach.

MASAM is a tool which is based on the

collection of the opinion of a number of experts

about the organization's environment (section 4.1). It

fundamentally consists in a series of transformations

that aggregate and analyze these opinions and

generate valuable information that would be hardly

obtainable from an unassisted analysis of the inputs

(section 4.2). A visualization tool (section 4.3) has

been developed specifically for MASAM (Monzani,

Bendahan et al. 2004), allowing a graphical

representation of this information, providing a

means to easily and intuitively interpret it.

4.1 The inputs

MASAM is a tool which is based on the collection,

aggregation and computation of the opinion of a

number of experts about certain aspects of the

organization's environment.

The first input is a list of the relevant actors and

issues, as defined in sections 3.2 and 3.3. All actors

which have a stake in the current situation and can

influence its outcome, either by influencing issues

directly or by influencing the other actors, should be

considered. As well, it is worth including all issues

which may disrupt the current environmental

conditions, especially those upon which actors have

sensibly diverging positions and means of influence.

The rest of the input consists in matrices that

take into account the influence relationships between

actor and issues or between pairs of actors. The

concepts used to link these elements are called

position, salience, clout and influence.

Position (Pos

a,i

) represents the preferred outcome

of an issue "i" to an actor "a". It is formalized as a

linear continuum between two extreme values on

which actors position themselves.

Salience (Sal

a,i

) denotes the importance of an

issue to an actor. It is measured by the relative utility

that the actor loses if the outcome is not close to

their position. Actors with high salience lose a lot of

utility, while less salient actor are less affected.

Clout (Clo

a,i

) represents the power that an actor

ICEIS 2004 - ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND DECISION SUPPORT SYSTEMS

126

has to influence an issue's outcome. The clout value

can be seen as the actual part of control of the issue.

It is supposed that the actors have, altogether, the

power to influence the issue's outcome along the

continuum on which the positions are set. If they

cannot fully influence an issue, a fictive actor

enacting the environmental trends may be used.

Finally, influence (Inf

a,b

) represents the ability of

an actor "a" to influence the decision of another

actor "b". It corresponds to a relationship of power

between the two actors, formalized as the part of

control of one actor over the other. This means that

actors do not have full control on themselves, but

their actions are partly commanded by other actors

that have means of pressure on them. The freedom

that an actor has over its choice represents the actor's

auto-determination coefficient.

The input matrixes can be filled with values of

any scale. They are subsequently standardized so as

to contain values ranging from 0 to 1.

The quality of the input is fundamental. For that

reason, a careful choice of experts is essential to

ensure input quality. In particular, it is suggested to

select experts who are representative of the different

actors’ opinions. Furthermore, it is suggested to use

some methods which can help fostering creativity

(e.g. brainstorming), consensus (e.g. Delphi surveys)

and collaboration (e.g. group support systems).

4.2 The transformations

MASAM proposes a set of transformations of the

input data that provide valuable information for

formulating strategic recommendations. The key

ones are presented below with the corresponding

equations: these allow users to assess indirect

influence, analyze the issues' outcomes and

disagreements, the actors’ true power repartition and

their proximity. Notice that MASAM extends the

Godet’s and Allas’ methods and can thus also

perform the same transformations proposed by them.

Indirect influence of order n (Inf(n)

a,b

) can be

calculated using the following formula to take into

account the fact that actors can not only influence

other actors directly, but also indirectly through

chains of influence passing through third parties.

The user can specify the order of indirect influence,

which defines the maximum length of these chains,

according to the chances that parties have to bargain.

The issues analysis allows the estimation of the

expected outcome (Outcome

i

) for all issues, which

can be calculated using different hypothesis such as

a pure vote based only on clout or integrating direct

or indirect influences. By comparing the actors’

positions with this outcome, it is possible to identify

the divergence of actors (Divergence

a,i

) so as to

identify the actors that may want to challenge the

outcome and how they want to change it.

The actors analysis enables to estimate the

true repartition of power (Power

a

) among actors

considering their clout on the different issues, as

their influence on other actors and the importance of

the different issues. Actors are also compared to

each other by looking at their general agreement on

the different issues: a proximity coefficient can be

calculated to illustrate potential conflicts and

coalitions.

4.3 Output analysis

Thanks to the visualization tool, the user can

obtain an intuitive representation of the output data

which clearly brings to light the key elements. The

most interesting graphs are illustrated thereafter

using data taken from a study of the Public Wireless

LAN industry in Switzerland. The study analyzed

seven actors. Due to lack of space, this example is

not described in this paper, but a description of the

study as well as the visualization tool can be found

in (Bendahan, Camponovo et al. 2003; Monzani,

Bendahan et al. 2004).

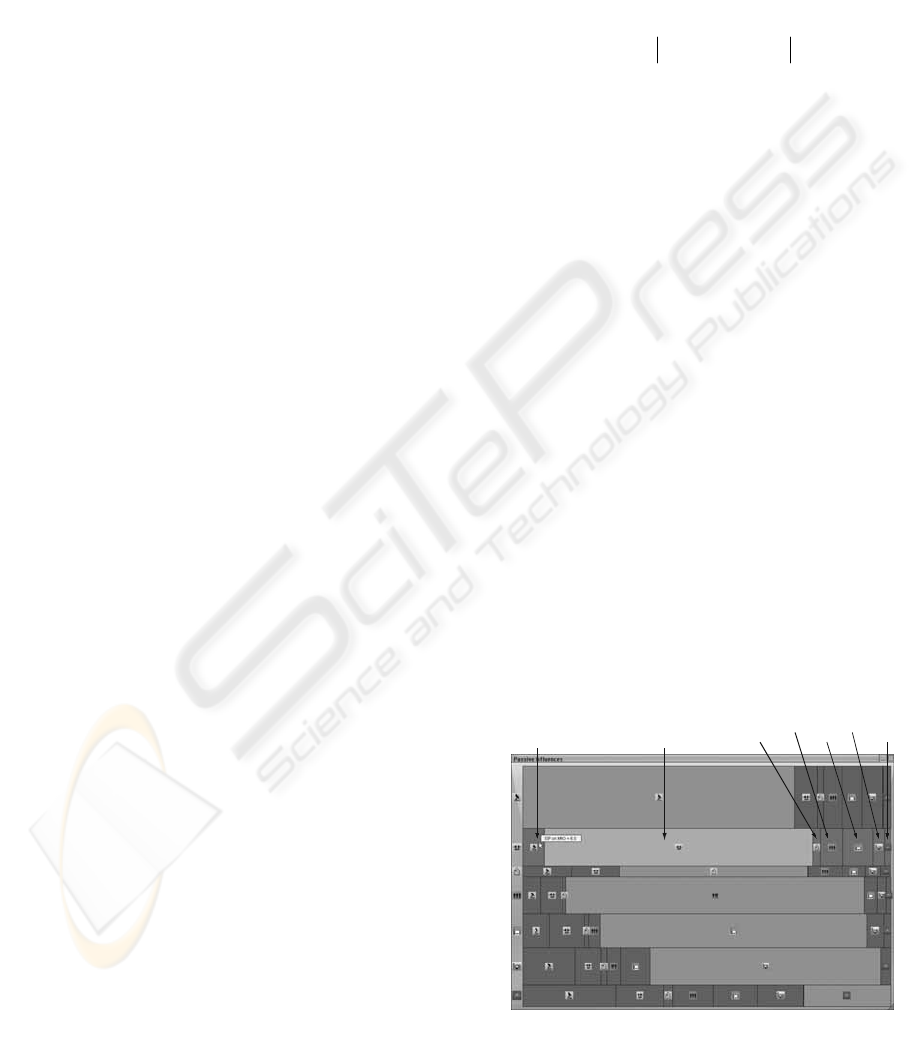

The influence graph (Figure 2) summarizes the

influence relationships between actors and their

relative power. Each horizontal bar represents an

actor. The height of this bar is proportional to the

actor's true power, while its length shows who

controls the subject actor. Actors that have a high

()

()

ba,ba,

c

bc,ca,ba,

c

bc,ca,ba,ba,

InfInf(0)

ba cb1)-Inf(n 1)-Inf(n Inf(n)

ba 1)-Inf(n 1)-Inf(n 1)-Inf(n Inf(n)

=

≠∀≠∀⋅=

=∀⋅+=

∑

∑

()

(

)

∑

∑

⋅⋅=

ic

c,ib,iba,a

SalClo Inf(N) Power

()

(

)

()

∑

∑

∑

⋅=

⋅⋅=

a

ia,iia,ia,

a

ba,ib,bia,i

SalOutcome - Pos Divergence

Inf(n) CloPos Outcome

Mobile Network

Operators

Wireline

ISP

Venues

Communities

Telephony

Informatics

Regulator

Mobile

Network

Operators

Wireline ISP

(currently

highlighted)

Venues

Communities

Telephony

Informatics

Regulator

Figure 2: Influence graph

STRATEGIC ANALYSIS OF THE ENVIRONMENT: A DSS FOR ASSESSING TECHNOLOGY ENVIRONMENTS

127

surface are therefore the most influent actors. This

graph can be helpful to view the different means of

pressure that actors can use in their negotiations. In

particular it can help to spot actors which can be

influenced to gain their support as well as consider

defensive strategies to prevent being influenced.

The issues analysis graph (Figure 3) shows the

issues’ expected outcome and the dissatisfaction of

actors on these issues. Each issue is represented as a

bar. The middle of the bar represents the issue’s

expected outcome. On this bar, the actors are placed

according to their dissatisfaction, which depends on

the actor’s position and salience. This graph can help

to identify the actors that are more likely to defend

or challenge the expected outcome: the more an

actor is far from the center, the more it is likely to

exhibit a strong will to challenge the expected

outcome. Actors can also spot their possible allies

and enemies on the different issues.

The relative power of actors is approximately

shown in the influence graph. However, a more

precise vision of the repartition of power can be

obtained from the power repartition graph (Figure

4) which shows how each issue is controlled. The

principle of the graph is similar to the influence

graphs: issues are represented as horizontal bars that

are divided according to the repartition of clout of

actors. The vertical sizes of the bars represent the

issues’ importance (average salience of actors).

Additional indications can be obtained from the

brightness of the surfaces, which is proportional to

the actor’s salience. Actors with large and bright

surfaces are very interesting negotiation parties, as

they can be easily convinced to make concessions

and have the power to influence the outcome.

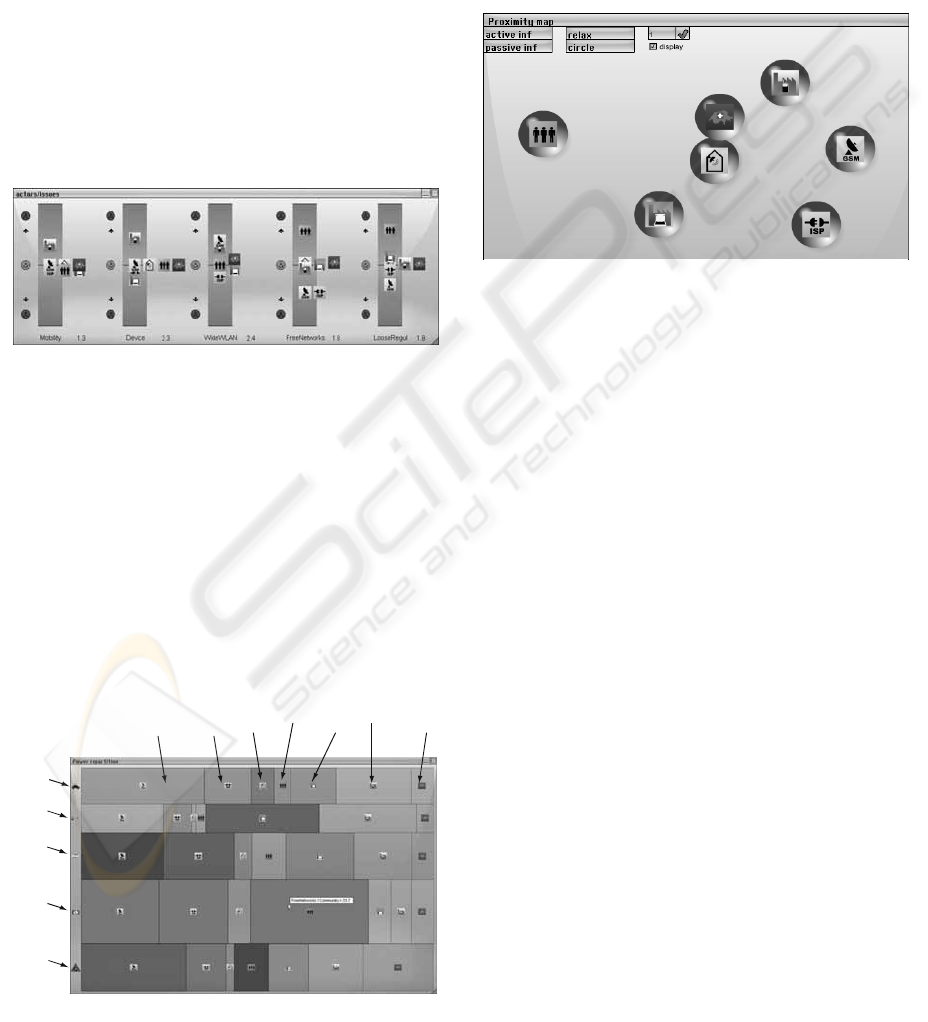

Finally, the proximity map (Figure 5) places the

actors on a 2D graph giving an overview of the

relative proximity of actors. Actors are positioned

according to their proximity coefficient, showing

how similar are their position on salient issues. This

graph can be used to spot the likely alliances and

conflicts: geographically compact groups of actors

will more likely form alliances, while far away ones

will more likely combat each other on a large

number of issues.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Environmental analysis is a hard task, because it

requires a huge amount of information which is hard

to identify and collect. Many different elements have

to be assessed and integrated to give strategists a

solid base upon which make their decision. For these

reasons, a decision support system is very valuable.

This paper intends to facilitate environmental

analysis by proposing an ontology of the relevant

elements to consider (i.e. markets, actors and issues)

and by suggesting a selection of tools to analyze and

visualize the information in these different

perspectives. In the longer term, we hope that these

elements will support and stimulate the development

of various decision support systems for assessing an

organization’s environment in a comprehensive and

systematic manner.

The usefulness of such systems was illustrated

by a prototype tool that proposes a partial analysis of

the global situation by integrating the issues and

actors perspectives. This tool is a first step towards

the conception and development of an integrated

system which assists the extensive analysis of the

environment from the three mentioned perspectives.

Finally, we also envision to devise a modified

scenario planning methodology which would take

advantage of the results of this environmental

analysis to possible to develop more grounded and

coherent future scenarios (Godet 2001).

Figure 5: Proximity map

Figure 3: Issue analysis graph

Mobile Network

Operators

Wireline

ISP

Venues

Communities

Telephony

Informatics

Regulator

Mobility

Device

Issues

Wide Area

WLAN

networks

Free

Networks

(currently

highlighted)

Loose

Regulation

Figure 4: Power repartition graph

ICEIS 2004 - ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND DECISION SUPPORT SYSTEMS

128

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The work presented in this paper was supported by

the National Competence Center in Research on

Mobile Information and Communication Systems

(NCCR-MICS), a center supported by the Swiss

National Science Foundation under grant number

5005-67322.

REFERENCES

Aguilar, F. J. (1967). Scanning the business environment.

Macmillan.

Allas, T. and N. Georgiades (2001). New tools for

negociators. McKinsey Quarterly. 2: 86-97.

Andrews, K. R. (1987). The concept of corporate strategy.

Dow Jones-Irwin.

Ansoff, H. I. (1980). "Strategic Issue Management."

Strategic Management Journal 1(2): 131-148.

Arcade, J., M. Godet, et al. (1999). Structural analysis

with the MICMAC method & Actor's strategy with

MACTOR method. CNAM: 70.

Bendahan, S., G. Camponovo, et al. (2003). "Multi-issue

actor analysis: tools and models for assessing

technology environments." To be published in Journal

of Decision Systems 12(4).

Boulding, K. E. (1956). "General Systems Theory - The

Skeleton of Science." Management Science 2(3): 197-

208.

Bourgeois, L. J. I. (1980). "Strategy and Environment: A

Conceptual Integration." Academy of Management

Review 5(1): 25-39.

Boyd, B. K. and J. Fulk (1996). "Executive Scanning and

Perceived Uncertainty: A Multidimensional Model."

Journal of Management 22(1): 1-21.

Bueno de Mesquita, B. and F. N. Stokman (1994).

European Community decision making models,

applications and comparisons. Yale University Press.

Camponovo, G. and Y. Pigneur (2003). Business Model

Analysis Applied to Mobile Business. ICEIS 2003.

Choo, C. W. (1994). "Perception and Use of Information

Sources in Environmental Scanning." Library &

Information Science Research 16(1): 23-40.

Choo, C. W. (1999). "The Art of Scanning the

Environment." Bulletin of the american society for

information science 25(3).

Choo, C. W. (2001). "Environmental scanning as

information seeking and organizational learning."

Information Research 7(1).

Christensen, C. M. and J. L. Bower (1996). "Customer

Power, Strategic Investment and the Failure of

Leading Firms." Strategic Management Journal 17:

197-216.

Daft, R. L., J. Sormunen, et al. (1988). "Chief Executive

Scanning, Environmental Characteristics and

Company Performance: An Empirical Study."

Strategic Management Journal 9(2): 123-139.

Dill, W. R. (1958). "Environment as an Influence on

Managerial Autonomy." Administrative Science

Quarterly 2(4): 409-443.

El Sawy, O. A. (1985). "Personal Information Systems for

Strategic Scanning in Turbulent Environments: Can

the CEO Go On-Line?" MIS Quarterly 9(1): 53-60.

Godet, M. (2001). Manuel de prospective stratégique.

Dunod.

Katz, D. and R. L. Kahn (1966). The social psychology of

organizations. Wiley.

Kotler, P. (2003). Marketing management. Prentice Hall.

Learned, E. p., C. R. Christensen, et al. (1965). Business

policy: text and cases. R. D. Irwin.

Martino, J. P. (2003). "A review of selected recent

advances in technological forecasting." Technological

Forecasting and Social Change 70(8): 719-733.

McQuarrie, E. F. (1996). The Market Research Toolbox:

A Concise Guide for Beginners, SAGE Publications.

Monzani, J. S., S. Bendahan, et al. (2004). Decision and

Visualization for Negotiation. HICSS, Hawaii.

Osterwalder, A. and Y. Pigneur (2002). An e-business

model ontology for modelling e-business. 15th Bled

Electronic Commerce Conference, Bled.

Pedersen, P. E. and R. Ling (2002). Mobile end-user

service adoption studies: A selective review. Working

Paper, Agder University College and Telenor R&D.

Pedersen, P. E. and R. Ling (2003). Modifying adoption

research for mobile Internet service adoption: Cross-

disciplinary interactions. HICSS, Hawaii.

Porter, M. E. (1980). Competitive strategy : techniques for

analyzing industries and competitors. The Free Press.

Porter, M. E. and V. E. Millar (1985). "How information

gives you competitive advantage." Harvard Business

Review 64(4): 149-160.

Rafii, F. and P. J. Kampas (2002). "How to identify your

enemies before they destroy you." Harvard Business

Review 80(11): 115-+.

Rugman, A. M. and A. Verbeke (2000). "Six cases of

corporate strategic responses to environmental

regulation." European Management Journal 18(4):

377-385.

Smith, W. (1956). "Product Differentiation and Market

Segmentation as Alternative Marketing Strategies."

Journal of Marketing 21: 3-8.

Stabell, C. and D. Fjeldstad (1998). "Configuring value for

competitive advantage: on chains, shops, and

networks." Strategic Management Journal (19): 413-

437.

Subramanian, R., N. Fernandes, et al. (1993).

"Environmental scanning in U.S. companies: their

nature and their relationship to performance."

Management International Review 33(3).

STRATEGIC ANALYSIS OF THE ENVIRONMENT: A DSS FOR ASSESSING TECHNOLOGY ENVIRONMENTS

129