THE SCOPE AND INTENSITY OF DERIVED BENEFITS FROM

E-COMMERCE PENETRATION IN SMES

Louis-A. Lefebvre

(1)

, Elie Elia

(2)

, Élisabeth Lefebvre

(1)

, Onno Omta

(3)

(1)

École Polytechnique de Montréal,

Mathematics and Industrial Engineering, P.O. Box 6079, Centre-Ville Station, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, H3C 3A7

(2)

Université du Québec à Montréal,

ESG, Management and Technology, P.O. Box 8888, succ. Centre-ville, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, H3C 3P8

(3)

Wageningen University,

Faculty of Management & Organization, 6700 EW, Bode 77, Postbus 8130, Netherlands

Keywords: E-commerce, cumulative benefits, organizational learning, SMEs.

Abstract: This paper attempts to (i) to assess the relative importance of benefits related to the gradual unfolding of

business-to-business e-commerce (B-2-B e-commerce) penetration among manufacturing SMEs and (ii) to

demonstrate that the scope and intensity of these benefits increase in the later stages of e-commerce

penetration as organizational learning gradually takes place. Empirical evidence strongly suggests that these

benefits are cumulative and that organizational learning allows SMEs to reap these benefits.

1 INTRODUCTION

Electronic commerce (e-commerce) has raised

considerable interest from public policy makers.

Their efforts were mainly directed to accelerate its

penetration among organizations, especially small-

and-medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and to create

a dynamic e-business environment (see for instance,

eEurope Action Plan, 2002; OECD 1998 and 2002;

US Department of Commerce, 2002a). But is e-

commerce more than technohype? Are the

expectations from e-commerce penetration

unrealistic in the context of SMEs? This paper

attempts to answer these questions but departs from

previous studies by pursuing the following two

objectives: (i) to assess the relative importance of

benefits related to the gradual unfolding of business-

to-business e-commerce (B-2-B e-commerce)

penetration among manufacturing SMEs and (ii) to

demonstrate that the scope and intensity of these

benefits increase in the later stages of e-commerce

penetration as organizational learning gradually

takes place. Our main goal is therefore to gain a

better understanding on how SMEs capitalize on the

potential of e-commerce.

2 RESEARCH FOCUS

2.1 Measuring E-commerce

Penetration from an Evolutionary

Perspective

B-2-B e-commerce continues to grow at a steady

pace, and its strategic impacts on organizations and

industries are increasing (OECD, 2002; Amit and

Zott, 2001). In this paper, B-2-B e-commerce is

defined broadly as “the use of Internet and related

technologies to support any activity that is necessary

for an organization to function effectively” (Magal

et al., 2001). E-commerce penetration in

organizations has been measured from different

perspectives. Some studies used measures of firms’

55

Lefebvre L., Elia E., Lefebvre É. and Omta O. (2004).

THE SCOPE AND INTENSITY OF DERIVED BENEFITS FROM E-COMMERCE PENETRATION IN SMES.

In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, pages 55-61

DOI: 10.5220/0002637000550061

Copyright

c

SciTePress

budget allocation for Internet and communication

technologies (ICTs), connectivity and type of ICTs

in use (Dutta and Evrard, 1999; Grandon and

Pearson, 2003; Riquelme, 2002; US Department of

Commerce, 2002b; Van Beveren and Thomson,

2002). Statistical agencies and some governmental

organizations were more interested in measuring

electronic transactions in numbers and dollar

volumes (Industry Canada, 2002; OECD, 2002;

Statistics Canada, 2001). Other studies focused on

business issues related to e-commerce and measured

e-commerce penetration by the type of activities it

supported or the business solutions that were

adopted (Bertchek and Fryges, 2002; Daniel et al.,

2002; Mirchandani and Motwani, 2001, Varian et

al., 2002).

Although the above approaches for measuring e-

commerce penetration may be useful for their

respective research objectives, they are of little help

in highlighting how these organizations are profiting

from using e-commerce. To be able to measure e-

commerce unfolding in organizations and its related

benefits, we need to measure e-commerce

penetration at its locus of impact: business

processes. This approach fits with Kauffman and

Weill’s (1989) view which emphasized the

importance of choosing the technology’s locus of

impact as the primary level of value analysis in IT

research. The process oriented approach yielded

interesting results in research on IT penetration and

its related benefits (Kauffman and Weill, 1989;

Barua et al., 1995; Tallon et al. 2000) and has also

been used in e-commerce research in both industry

case studies (Subramaniam and Shaw, 2002) and

survey studies (Barua et al. 2001; Zhu and Kraemer,

2002; Lefebvre and Lefebvre, 2003). Zhu and

Kraemer (2002) focused on the dynamic capabilities

perspective and translated “net-enabled processes”

into “e-commerce capabilities”: information,

transaction, interaction and supplier integration.

More recently, Lefebvre and Lefebvre (2003) went

one step further and proposed an e-commerce

penetration trajectory model based on sequential

stages of e-commerce penetration. Their approach

draws on the evolutionary perspective (Nelson and

Winter, 1982) of the dynamic capabilities theory and

represents a useful starting point to better explore

the relationship between e-commerce penetration

levels and their derived benefits.

2.2 Manufacturing SMEs and

E-commerce

According to the US department of commerce

(2002b), manufacturing continues to lead other US

sectors in terms of electronic commerce shipments.

Some researchers have even related the productivity

growth in the US manufacturing sector, between

1995 and 2000, to the surge of the Internet and e-

commerce (McAfee, 2002). Manufacturing SMEs

continue to play a major economic role in all

industrialized economies (Stevenson and Lundström,

2001) and are increasingly pressured by big

manufacturers to adopt e-commerce. SMEs’ limited

financial and non-financial resources makes it more

crucial for them to adequately harness value from e-

commerce initiatives and render the trajectory

approach even more adequate.

2.3 E-commerce Benefits

From the literature review, we have divided the

benefits associated to B-2-B e-commerce (see for

instance, Turner, 2000; Hocque, 2003; Turban et al.,

2002) into four main areas which are considered as

crucial in the context of manufacturing SMEs:

(i) costs reductions by lowering transaction costs

and inventory levels or by gaining economies of

scale (through group buying or purchase

consolidation);

(ii) cycle time reductions with lower lead times,

faster product design or speedier ordering of parts

and components;

(iii) quality increases especially with improved

customer relationships; and

(iv) growth in revenues as e-commerce represents,

especially for the smaller firms, a low cost way to

expand markets and to effectively target market

segments.

Benefits associated with B-2-B e-commerce may

be even more compelling as they are derived from

collaboration between business partners but remain

an under-investigated issue (Gebauer and Shaw,

2002; Kendall et al., 2001).

3 METHODOLOGY

3.1 The E-survey

A systematic sample was drawn from an up-to-date

government list of all manufacturing SMEs

operating in one Canadian province which includes

basic information on each firm such as number of

employees, volume of sales, geographic location and

coordinates including the electronic address of the

CEO. SMEs are here defined as firms with less than

500 employees, a definition in accordance with

some governmental agencies such as the US Small

Business Administration. An electronic

ICEIS 2004 - SOFTWARE AGENTS AND INTERNET COMPUTING

56

questionnaire was sent to the Chief Executive

Officer (CEO) of each of the selected firms. The

total number of SMEs participating to the on-line

survey was 230 firms and the response rate reached

7.6% which is quite acceptable for this type of

survey. Non-response bias does not seem to exist

with respect to firm size as no significant differences

(goodness of fit tests) were found but there is a

slight positive bias towards urban areas.

Furthermore, the use of an e-survey may indeed

underestimate the number of non-adopters of e-

commerce. However, this later issue represents a

shortcoming that tends to disappear as smaller firms

have gained in the last few years a generalized

access to the Internet. In the case of Canadian SMEs

that are in a vast majority linked to the Internet, this

shortcoming appears minimal in comparison to the

cost effectiveness, efficiency and conviviality

offered by e-surveys (Couper, 2000; Rogelberg et

al., 2001; Dillman, 2000).

3.2 Research Variables

3.2.1 E-commerce Penetration

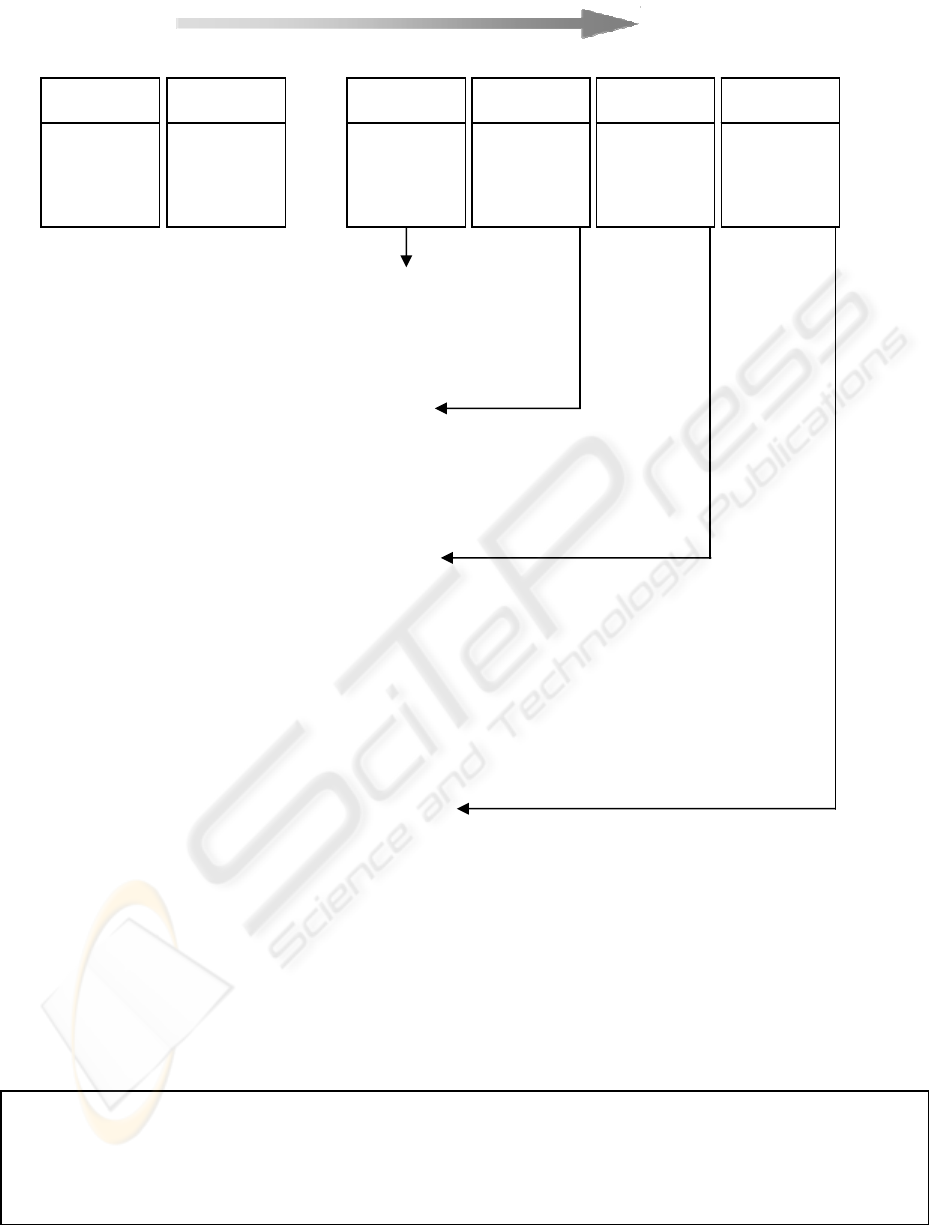

This article builds on previous work conducted by

Lefebvre and Lefebvre (2003) who proposed a six-

stage model that differentiates the non-adopters from

the adopters (upper part of figure 1). Stage 00 and

stage 0 correspond to non-adopters which are not the

focus of this paper. Stages 1, 2, 3 and 4 represent e-

commerce adopters. Stage 1 is limited to electronic

information search and content creation. Stage 2

represents simple e-transactions while stage 3

includes online transactions of increased complexity

such as conducting electronic auctions and

negotiating contracts online. Stage 4 considers a

wider range of e-commerce capabilities that support

e-collaboration activities with customers and

suppliers.

In order to capture different stages of B-2-B e-

commerce penetration (stages 1, 2, 3 and 4), we

have identified and validated 36 business processes

that could be supported electronically (middle part

of figure 1). These processes were also evaluated

with respect to their relative level of complexity by a

panel of 12 experts. Inter-rater reliability between

members of the panel proved to be excellent for

most business processes (ranging from 0.7 to 1.0)

and satisfactory for the remaining ones (r = 0.6).

The mean level of complexity for all stage 1

processes was 1.504, 2.829 for stage 2 processes,

3.547 for stage 3 processes and 4.698 for stage 4

processes. Thus, supporting the fact that complexity

increases with the stages.

The score of e-commerce penetration in one

particular firm simply represents the sum of business

processes that are carried out using electronic means

(

∑

=

36

1

BP

i

i ). To reflect e-commerce initiatives’

complexity, a weighted score could also be

derived:

∑

=

36

1

BP x c

i

ii (where BP

i

corresponds to the

business processes listed in figure 1 and c

i

= level of

complexity of each business process as rated by the

panel of 12 experts). These scores were thoroughly

validated (Lefebvre and Lefebvre, 2003; Elia et al.,

2004).

3.2.2 Derived Benefits

The benefits associated to e-commerce are all based

on perceptual measures using 7-point Likert scales.

They are derived from the literature review and

reflect the manufacturing environment in which

these firms operate. The exact wording was

validated through on-site interviews with the CEOs

of 15 SMEs

.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Profile of Responding Firms

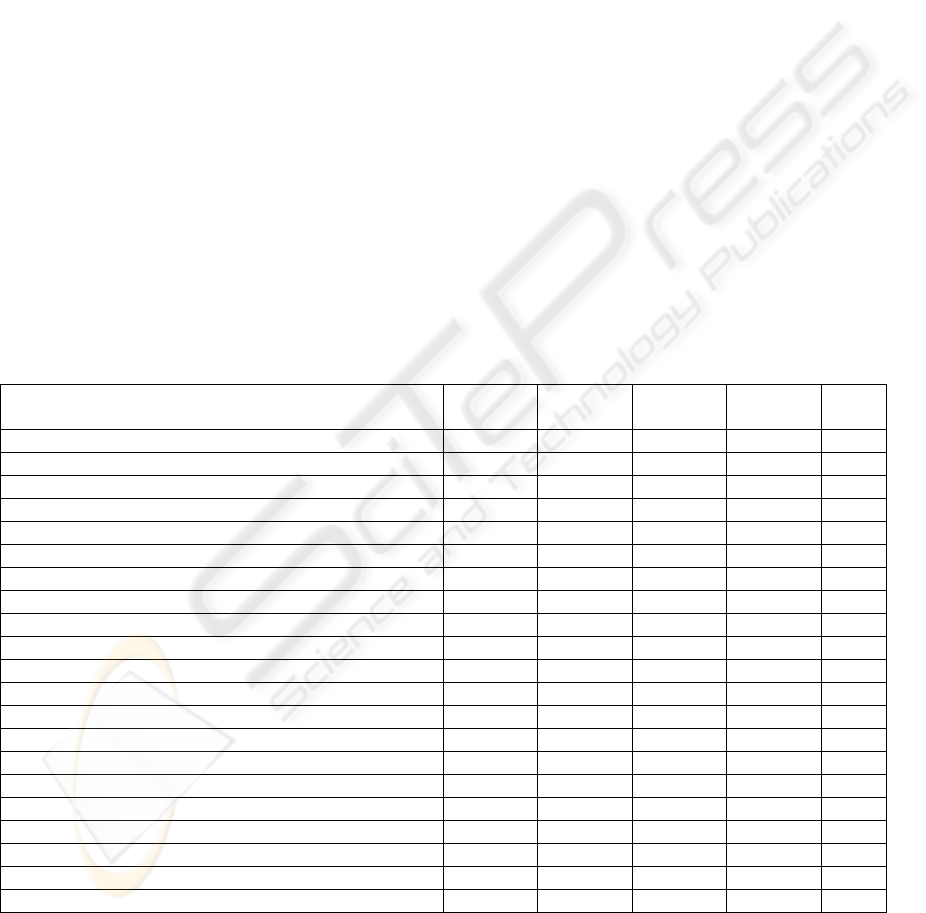

As can be seen from the data presented in Appendix

1, firms in the different stages do not differ

significantly with respect to size although more

advanced firms tend to be larger. However, firms in

stage 3 and 4 do seem to be significantly

internationalized.

Scores of e-commerce penetration increase with

the stages as does the volume of e-transactions (p =

0.0000). These results further validate the stage

model.

4.2 The Scope and Intensity of

Derived Benefits

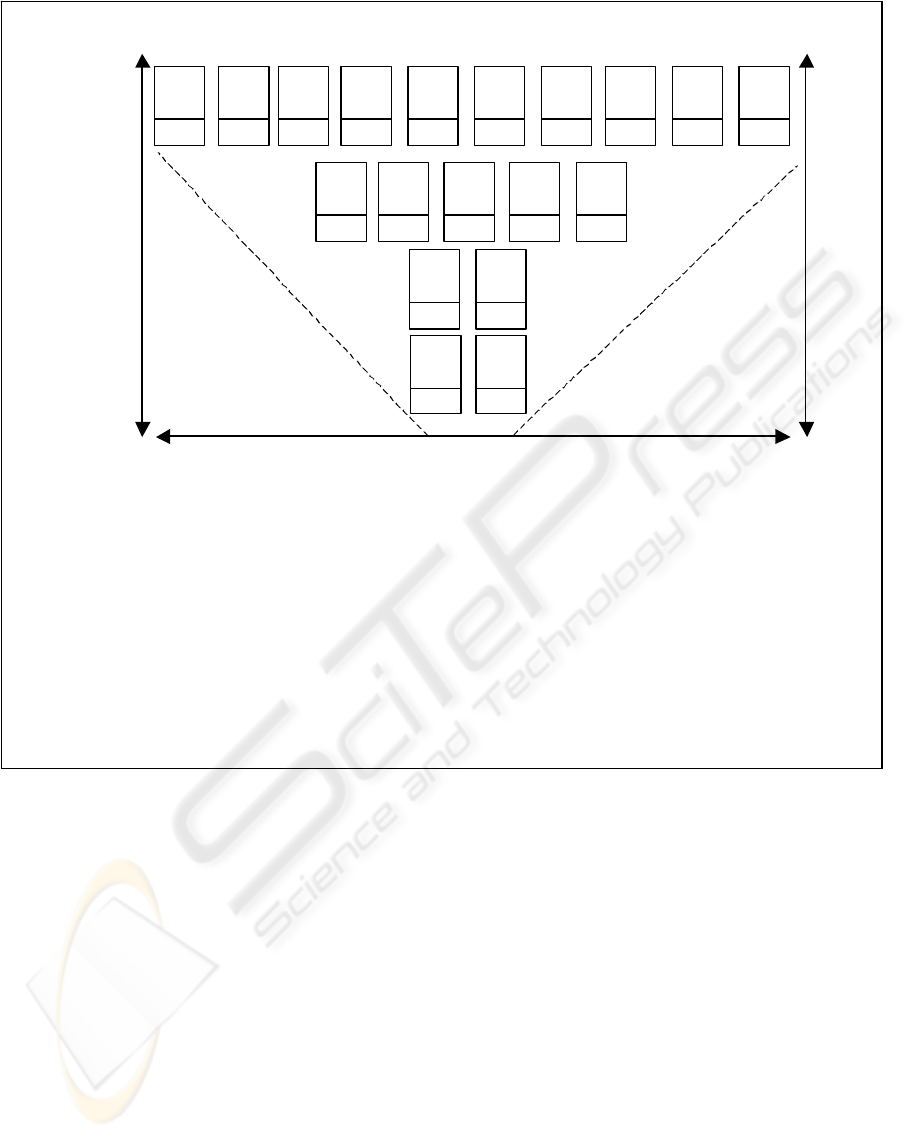

In order to evaluate the scope and intensity of

perceived benefits from e-commerce penetration,

CEOs were asked to evaluate on a seven point scale

(7 being the highest) ten potential benefits. Firms

belonging to each of the four stages of e-commerce

penetration were characterized according to the

benefits they derived from the utilization of e-

commerce business processes. It was decided to

retain only those benefits that ranked 3 or higher on

the 7 point-scale for each group of firms.

THE SCOPE AND INTENSITY OF DERIVED BENEFITS FROM E-COMMERCE PENETRATION IN SMEs

57

Business Processes (BP

i

):

Stage 1: Electronic information search & content creation

• Seek out new suppliers

• Seek out products/services

• Advertise the company and/or its products/services

• Seek out new customers

• Convert information on products/services into digital form

Stage 2: Electronic transactions

• Buy products/services using electronic catalogs

• Place and manage orders with suppliers

• Access suppliers’ product/service databases

• Sell products/services using electronic catalogs

• Receive and manage customer orders

• Access customers’ product/service databases

• Offer customers after-sales services

Stage 3: Complex electronic transactions

• Buy products/services by electronic auction

• Buy products/services by issuing electronic calls for tenders

• Negotiate contracts (price, volume, etc.) with suppliers

• Make electronic payments to suppliers

• Sell products/services by electronic auction

• Sell products/services by responding to electronic calls for tenders

• Negotiate contracts (price, volume, etc.) with customers

• Receive electronic payments from customers

• Allow customers to access the company’s inventories

• Access customers’ inventories

• Allow suppliers to access the company’s inventories

• Access suppliers’ inventories

Stage 4: Electronic collaboration

• Transfer documents and technical drawings to customers

• Transfer documents and technical drawings to suppliers

• Integrate software supporting product design (e.g. CAD/CAM, VPDM, PDM)

• Do collaborative on-line engineering with suppliers

• Do collaborative on-line engineering with customers

• Automate the production floor using a manufacturing execution system (MES)

• Integrate the MES into the management information system

• Ensure the management of quality assurance using the management information system

• Automate distribution/logistics using a logistics execution system (LES)

• Allow distribution/transportation partners to access the information they need (SKU, quantity, delivery turnaround, etc.) in order

to reduce time and costs related to distribution

• Optimize returns management (“reverse logistics”)

• Track products (purchased and sold) during transportation

Score of e-commerce penetration

∑

=

=

36

1

BP

i

i

; and weighted score of e-commerce penetration

∑

=

=

36

1

BP x ic

i

i

.

Where BP

i

corresponds to the Business Processes listed above (BP

i

=0 when BP

i

is not conducted in one particular firm

using electronic means and BP

i

=1 when it is) and c

i

= degree of complexity of each Business Process as rated by a panel of 12 experts.

Figure 1: Stage model for e-commerce penetration among manufacturing SMEs

Stage 00

Stage 0 Stage

1 Stage 2 Stage 3 Stage 4

Non-adopters

with no interest

in e-com

Non-adopters

with interest

in e-com

Electronic

information

search & content

creation

Electronic

transactions

Complex

electronic

transactions

Electronic

collaboration

Non adopters Adopters

ICEIS 2004 - SOFTWARE AGENTS AND INTERNET COMPUTING

58

Where:

Q-CS = Increase in customer service quality.

C-M, S, AS = Reduction in marketing, sales and after-sales costs.

T-D = Reduction in delivery time (speed or dependability).

R-MS = Increase in market share.

R = Increase in revenues.

C-P = Reduction in procurement costs.

C-E = Reduction in engineering, product development and design costs.

C-M = Reduction in manufacturing and inventory costs.

T-M = Reduction in product manufacturing cycle time.

C-L = Reduction in logistics and distribution costs.

Intensity of derived benefits is captured by 7 point Likert scales (where 1= very low and 7= very high).

Figure 2: Scope and intensity of derived benefits

The results of this exercise are presented in figure

2. The corresponding analysis is conducted with

respect to both scope (number of concurrent

benefits that ranked 3 or higher) and intensity (the

level of the derived benefits on the 7 point-scale

for any one of the 10 benefits).

With respect to scope, it becomes generally

evident that the number of concurrent benefits

increases with the stages of e-commerce

penetration, although stages 1 and 2 share the same

benefits which are interestingly enough related to

customer service and cost reductions in client

related activities. The fact that the benefits in the

first two stages share a common focus may be

explained by the time lag required to achieve these

benefits and by unrealistic expectations with

respect to time and outcomes on the part of the

SMEs. In stage 3, firms tend to experience an

increase in the scope of benefits with other added

customer oriented activities like delivery time and

with increases in market share and revenues. Only

in stage 4 do firms derive benefits associated with

increases in engineering, manufacturing, and

overall logistics efficiency. This indicates that

these may be the most difficult to obtain and that

they are captured as a result of a rather long

learning process since they affect product related

creation, realization and distribution processes.

In terms of intensity, it is also observable from

appendix 1 that the level of intensity increases for

most of the benefits as SMEs progress in the later

stages of B-2-B e-commerce penetration: this

suggests again a learning process through which

firms evolve. This positive learning trajectory is

important as it stresses the fact that SMEs get

better over time and that the continued use of e-

commerce processes does translate into mounting

benefits with respect to both intensity and scope.

Scope of derived benefits

Stages of

e-

commerce penetration

Stage 4

Electronic

collaboration

Stage 3

Complex

electronic

transactions

Stage 2

Electronic

transactions

Stage 1

Electronic

information

search and

content

creation

T-D

Q-

CS

C-

M

,

S,

AS

R-

MS

R

Q-

CS

C-

M,S,

AS

Q-

CS

C-

M

,

S,

AS

Intensity of derived

benefits

3.37

3.51

3.26

3.91

3.35

3.00

4.17

3.67

3.67

3.45

3.26

3.31

3.78

3.78

3.90

4.68

4.103.97

3.63

C-P

C-E

T-D

Q-

CS

C-

M

,

S,

AS

R-

MS

R

C-M

T-M

C-L

THE SCOPE AND INTENSITY OF DERIVED BENEFITS FROM E-COMMERCE PENETRATION IN SMEs

59

5 CONCLUSION

This paper is an attempt to demonstrate how

benefits associated with e-commerce in SMEs

differ as the level of penetration of e-commerce

processes in firms increases. An e-commerce stage

model was presented with a spectrum ranging from

rather basic e-commerce processes such as

electronic information search (stage 1) to more

complex processes such as collaboration activities

with customers and suppliers (stage 4).

Furthermore, it was shown that the scope

(number of benefits) and intensity (number of

derived benefits) of these benefits also increases as

a firm moves up in the e-commerce stage model

indicating that there exists a learning process

which allows firms to reap increasing benefits over

time. This suggests the existence of an

evolutionary pattern with respect to both realized

e-commerce penetration and derived e-commerce

benefits in SMEs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the two reviewers

for their insightful comments and gratefully

acknowledge supports from FCAR and SSHRC.

REFERENCES

Amit, R. and Zott, C., 2001. Value creation in e-

business. Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 22,

No. 6/7, pp.493-520.

Barua, A., Kriebel, C.H. and Mukhopadhyay, T., 1995.

Information Technologies and Business Value: An

Analytic and Empirical Investigation. Information

Systems Research, Vol. 6, No. 1, pp. 3-21.

Barua, A., Konana, P., Whinston, A.B. and Yin, F.,

2001. Driving E-Business Excellence. MIT Sloan

Management Review, Vol. 43, No. 1, pp. 36-44.

Bertschek, I. and Fryges, H., 2002. The Adoption of

Business-to-Business E-Commerce: Empirical

Evidence for German Companies. Paper 02-05,

Centre for European Economic Research, Mannheim.

Couper, M.P., 2000. Usability Evaluation of Computer-

Assisted Survey Instruments. Social Science

Computer Review, Vol. 18, No. 4, pp. 384-396.

Daniel, E., Wilson, H. and Myers, A., 2002. Adoption of

E-Commerce by SMEs in the UK, Towards a Stage

Model. International Small Business Journal, Vol.

20, No. 3, pp. 253-270.

Dillman, D.A., 2000. Mail and Internet Surveys: The

Tailored Design. New York: John Wiley.

Dutta, S. and Evrard, P., 1999. Information Technology

and Organization within European Small Enterprises.

European Management Journal, Vol. 17, No. 3, pp.

239-251.

Elia, E., Lefebvre, L.A. and Lefebvre, É., 2004.

Typology of B-to-B E-comerce Initiatives and

Related Benefits in Manufacturing SMEs.

Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International

Conference on Systems Sciences, Hawaii: IEEE.

Forthcoming.

eEurope, 2002. An Information Society for All, Action

Plan 2002 and 2005.

http://www.europa.eu.int/informationsociety/eeurope

/actionplan.

Gebauer, J., and Shaw, M.J., 2002. Introduction to the

Special Section: Business-to-Business Electronic

Commerce”, International Journal of Electronic

Commerce, Vol. 6, No. 4, pp. 7-17.

Grandon, E. E. and Pearson J.M., 2003. Perceived

Strategic Value and Adoption of Electronic

Commerce: An Empirical Study of Small and

Medium Sized Businesses. Proceedings of the 36th

Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences.

Honolulu: IEEE.

Hocque, F., 2000. E-enterprise: Business Models,

Architecture and Components. Cambridge

University Press, Cambridge.

Industry Canada, 2002. Key Indicators on ICT

Infrastructure, Use and Content. Report, Ottawa.

Kauffman, R. J., and Weill, P., 1989. An Evaluative

Framework for Research on the Performance Effects

of Information Technology Investment. Proceedings

of the Tenth International Conference on

Information Systems, Boston.

Kendall, J., Tung, L.L., Chera, K.H., Ng, C.H. and Tan,

S.M., 2001. Electronic Commerce adoption by

SMEs in Singapore. Proceedings of the 34th Hawaii

International Conference on Systems Sciences.

Honolulu: IEEE.

Lefebvre, É., and Lefebvre, L.A., 2003. E-commerce

Adoption Trajectories Among Manufacturing SMEs,

Proceedings of IADIS Conference,Portugal.

Magal, S.R., Feng, M. and Essex, P.A., 2001. An

Exploratory Study of Web-Based Electronic

Commerce Applications. Journal of Information

Technology Theory and Application, Vol. 3, No. 5,

pp. 139-149.

McAfee, A., 2002. The Impact of Enterprise Information

Technology Adoption on Operational Performance:

An Empirical Investigation. Production and

Operations Management

, Vol. 11, No. 1, pp. 33-53.

Mirchandani, A. and Motwani, J., 2001. Understanding

Small Business Electronic Commerce Adoption: An

Empirical Analysis. Journal of Computer

Information Systems, Spring 2001, pp. 70-73.

Nelson, R.R. and Winter, S., 1982. An Evolutionary

Theory of Economic Change. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard Business Press.

OECD, 1998. SMEs and Electronic Commerce. Paris:

Directorate for Science, Technology and Industry.

ICEIS 2004 - SOFTWARE AGENTS AND INTERNET COMPUTING

60

OECD, 2002. Measuring the Information Economy.

Paris: OECD Publications.

Riquelme H., 2002. Commercial Internet Adoption in

China: Comparing the Experience of Small, Medium

and Large Businesses. Internet Research, Vol. 12,

No. 3, pp. 276-286.

Rogelberg, S.G., Fisher, G.G., Maynard, D.C., Hakel

M.D. and Horvath, M., 2001. Attitudes Toward

Surveys: Development of a Measure and its

Relationship to Respondent Behavior.

Organizational Research Methods, Vol. 40, No. 1,

pp. 3-25.

Statistics Canada, 2001. Electronic Commerce and

Technology Use. Ottawa: Connectedness Series.

Stevenson, L. and Lundström, A., 2001. Patterns and

trends in entrepreneurship/SME policy and practice

in ten economies. Swedish Foundation for Small

Business Research, Stockholm.

Subramaniam, C., and Shaw, M.J., 2002. A Study of the

Value and Impact of B2B E-Commerce: The Case of

Web-Based Procurement. International Journal of

Electronic Commerce, Vol. 6, No. 4, pp. 19-40.

Tallon, P. P., Kraemer, L. K. and Gurbaxani, V., 2000.

Journal of Management Information Systems. Vol.

16, No. 4. pp. 145-173.

Turban, E., David King, J.L., Warkentin, J.L. and H.M.,

M., 2002. Chung, Electronic Commerce 2002: A

Managerial Perspective, Prentice-Hall, Upper

Saddle River, New Jersey.

Turner, C., 2000. The Information E-conomy, Kogan

Page, London.

US Department of Commerce, 2002a. Main Street in the

Digital Age: How Small and Medium-Sized

Businesses Are Using the Tools of the New Economy.

Washington DC: Economics and Statistics

Administration.

US Department of Commerce, 2002b. E-Stats 2000.

Washington DC: US Census Bureau.

Van Beveren, J. and Thomson, H., 2002. The Use of

Electronic Commerce by SMEs in Victoria,

Australia. Journal of Small Business Management,

Vol. 40, No. 3, pp. 250-253.

Varian, H., Litan, R.E., Elder A. and Shutter, J., 2002.

The Net Impact Study. Available at:

www.netimpactstudy.com.

Zhu, K. and Kraemer, K.L., 2002. E-Commerce Metrics

for Net-Enhanced Organizations: Assessing the

Value of E-Commerce to Firm Performance in the

Manufacturing Sector. Information Systems

Research, Vol. 13, No. 3, pp. 275-295.

APPENDIX 1

The stage model: SMEs’ characteristics, e-commerce adoption and benefits

Stage 1

(n=8)

Stage 2

(n=17)

Stage 3

(n=47)

Stage 4

(n=50)

p

(4)

SMEs’ characteristics

Size (annual sales in $CAN) 18.13M 23.34M 84.46M 139.19M NS

Level of exports (1) 11.95% 8.78% 17.12% 16.97% **

Level of imports (1) 12.14% 8.12% 20.61% 32.45% ***

E-commerce adoption

Score of e-commerce adoption (2) 1.88 3.88 6.55 10.58 ****’

Weighted score of e-com. Adoption (2) 2.79 8.22 15.66 31.93 ****’

Volume of e-transactions

% of e-sales (3) 0.00% 1.43% 9.29% 12.58% ****

% of e-procurement (3) 0.00% 0.98% 16.59% 21.27% ****

Benefits derived from e-commerce adoption

Increase in customer service quality 3.67 4.17 3.91 4.68 NS

Reduction in marketing, sales & after-sales costs 3.67 3.00 3.26 3.90 NS

Reduction in delivery time (speed/dependability) 2.33 2.58 3.35 4.10 *

Increase in market share 2.83 2.92 3.51 3.78 *

Increase in revenues 2.33 2.58 3.37 3.78 *

Reduction in procurement costs 2.83 2.67 2.91 3.63 NS

Reduction in eng., product develop. & design costs 2.00 2.25 2.24 3.97 ***

Reduction in manufacturing & inventory costs 2.00 2.00 2.15 3.31 **

Reduction in product manufacturing cycle time 2.17 2.42 2.38 3.26 NS

Reduction in logistics & distribution costs 2.50 2.50 2.68 3.45 NS

(1) Level of exports: ratio of sales realized in foreign markets over total sales. Level of imports: ration of purchases from foreign markets

over total purchases. (2) As defined in figure 1. (3) Ratio of e-sales over total sales. Ratio of e-procurement over total procurement. (4) p=

level of significance of the Kruskall Wallis Test (non-parametric ANOVA) * = p<0.10; ** = p<0.05 ; *** = p<0.01 ; **** = p<0.001.

THE SCOPE AND INTENSITY OF DERIVED BENEFITS FROM E-COMMERCE PENETRATION IN SMEs

61