ACCESSIBILITY AND VISUALLY IMPAIRED USERS

António Ramires Fernandes and Jorge Ribeiro Pereira and José Creissac Campos

Departamento de Informática, Universidade do Minho

Portugal

Keywords:

Accessibility, Internet, Visually impaired users, talking browsers

Abstract:

Internet accessibility for the visually impaired community is still an open issue. Guidelines have been issued

by the W3C consortium to help web designers to improve web site accessibility. However several studies

show that a significant percentage of web page creators are still ignoring the proposed guidelines. Several

tools are now available, general purpose, or web specific, to help visually impaired readers. But is reading a

web page enough? Regular sighted users are able to scan a web page for a particular piece of information at

high speeds. Shouldn’t visually impaired readers have the same chance? This paper discusses some features

already implemented to improve accessibility and presents a user feedback report regarding the AudioBrowser,

a talking browser. Based on the user feedback the paper also suggests some avenues for future work in order

to make talking browsers and screen readers compatible.

1 INTRODUCTION

Internet accessibility is still an issue for people with

disabilities, in particular for the visually impaired

community. Web pages are designed based on the vi-

sual impact on the visitor with little or no concern for

visually impaired people. HTML is commonly used

as a design language and not as a content language.

Two types of complementary directions have

emerged to help the visually impaired community:

• Raising the awareness of developers to accessibil-

ity issues and providing appropriate methods for

web development and evaluation, see for example

(Rowan et al., 2000);

• Developing tools that assist visually impaired users

to navigate the web.

Sullivan and Matson (Sullivan and Matson, 2000)

state that popular press typically reports that 95% or

more of all Web sites are inaccessible to users with

disabilities. The study in (Sullivan and Matson, 2000)

shows a not so dark picture by performing a contin-

uous accessibility classification. Nevertheless the pa-

per still concludes that "...many Web designers either

remain ignorant of, or fail to take advantage of, these

guidelines" (Web Content Accessibility Guidelines by

WC3).

Sanborn et. al. (Jackson-Sanborn et al., 2002) per-

formed an evaluation of a large number of sites and

concluded that 66.1% failed accessibility testing.

Developing strategies to make web pages more ac-

cessible is a solution proposed by many researchers.

For instance Filepp et. al. (Filepp et al., 2002) pro-

pose an extension for HTML tables. Adding specific

tags to HTML tables would allow web page designers

to add contextual information.

However these extensions are still a long way from

becoming a standard. Furthermore, even when they

do become a standard, there is still the issue of getting

web designers to follow them. The W3C Guidelines

have been around for quite some time and the results

from (Jackson-Sanborn et al., 2002) and (Sullivan and

Matson, 2000) show that a large percentage of web

designers do not follow the proposed guidelines.

Based on these studies we can conclude that ac-

cessibility for the visually impaired community re-

mains an issue. Some solutions have emerged to help

this particular community of disabled people provid-

ing tools that assist users to navigate the web. These

solutions can be categorized regarding their scope:

General Purpose Screen readers

Web Specific Talking Web browsers and Transcod-

ing

Screen readers provide a general purpose solution

75

Ramires Fernandes A., Ribeiro Pereira J. and Creissac Campos J. (2004).

ACCESSIBILITY AND VISUALLY IMPAIRED USERS.

In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, pages 75-80

DOI: 10.5220/0002641100750080

Copyright

c

SciTePress

to the accessibility problem for the visually impaired

community. Their main advantage is being able to

single handedly deal with most software. However

this lack of specificity also implies that screen read-

ers are not optimized to deal with any application in

particular.

IBM(IBM, 2000) proposes a transcoding system to

improve web accessibility which explores similarities

between a web page and its neighboring. Common

layout structure is then removed, hopefully retaining

the important parts of the page.

Talking browsers such as IBM’s Homepage

Reader

1

, Brookes Talk

2

(Zajicek et al., 2000) and the

AudioBrowser

3

(Fernandes et al., 2001), on the other

hand offer a solution to specific tasks: web browsing

and e-mail. Being specific solutions they are unable

to deal with other tasks besides web surfing. Never-

theless a specific solution can represent a significant

advantage to the user.

Talking browsers and transcoding approaches can

take advantage of the underlying structure of the doc-

ument, and present different views of the same docu-

ment to the user.

In this paper we shall explore the avenue of solu-

tions based on talking browsers. In section 2 we shall

focus mainly on features offered by these applications

that improve real accessibility. Section 3 reports on

the feedback provided by users of a particular solu-

tion, the Audiobrowser. Conclusions and some av-

enues for future work are proposed in section 4.

2 TALKING BROWSERS

In this section some features and issues related to talk-

ing browsers web solutions are presented. The focus

is mainly on features that provide an added value to

the user and not on basic features such as basic navi-

gation.

2.1 Integration

An important issue in these solutions is to allow the

visually impaired user to share its web experience

with regular and near sighted users. All the solutions

presented in the first section deal with this issue. The

IBM approach is to allow users to resize the window,

fonts, and colors. An alternative approach is used

both by the Brookes Talk and the AudioBrowser: a

distinct area where the text which is being read is dis-

played in a extra large font. These areas can be resized

1

Available at

http://www-3.ibm.com/able/solution_offerings/hpr.html

2

Available at http://www.brookes.ac.uk/schools/cms/

research/speech/btalk.htm

3

Available at http://sim.di.uminho.pt/audiobrowser

to a very large font making it easier for even seriously

near-sighted users to read the text.

All solutions also provide a standard view of the

page therefore allowing the visually impaired and

near-sighted users to share their experience with reg-

ular sighted users. This feature is essential to allow

for full inclusion of users with disabilities in the In-

formation Society.

2.2 Document Views

The Brookes Talk solution provides an abstract of the

web page comprising key sentences. This approach,

reduces the amount of text to about 25% and therefore

gives the user an ability to quickly scan the contents

of the page.

The AudioBrowser includes a feature that attempts

to get the user as quickly as possible to the page’s

contents. A significant number of web pages has a

graphical layout based on two or three columns. The

first column usually contains a large set of links, and

the main contents is on the second column. Normal

reading of one of such pages implies that the user

must first hear the set of links before the application

reaches the main content itself. In order to get the

user as quickly as possible to the main contents of the

web page the links are removed. This eliminates most

of the content of the first column, therefore the user

reaches the main content with just a few key strokes.

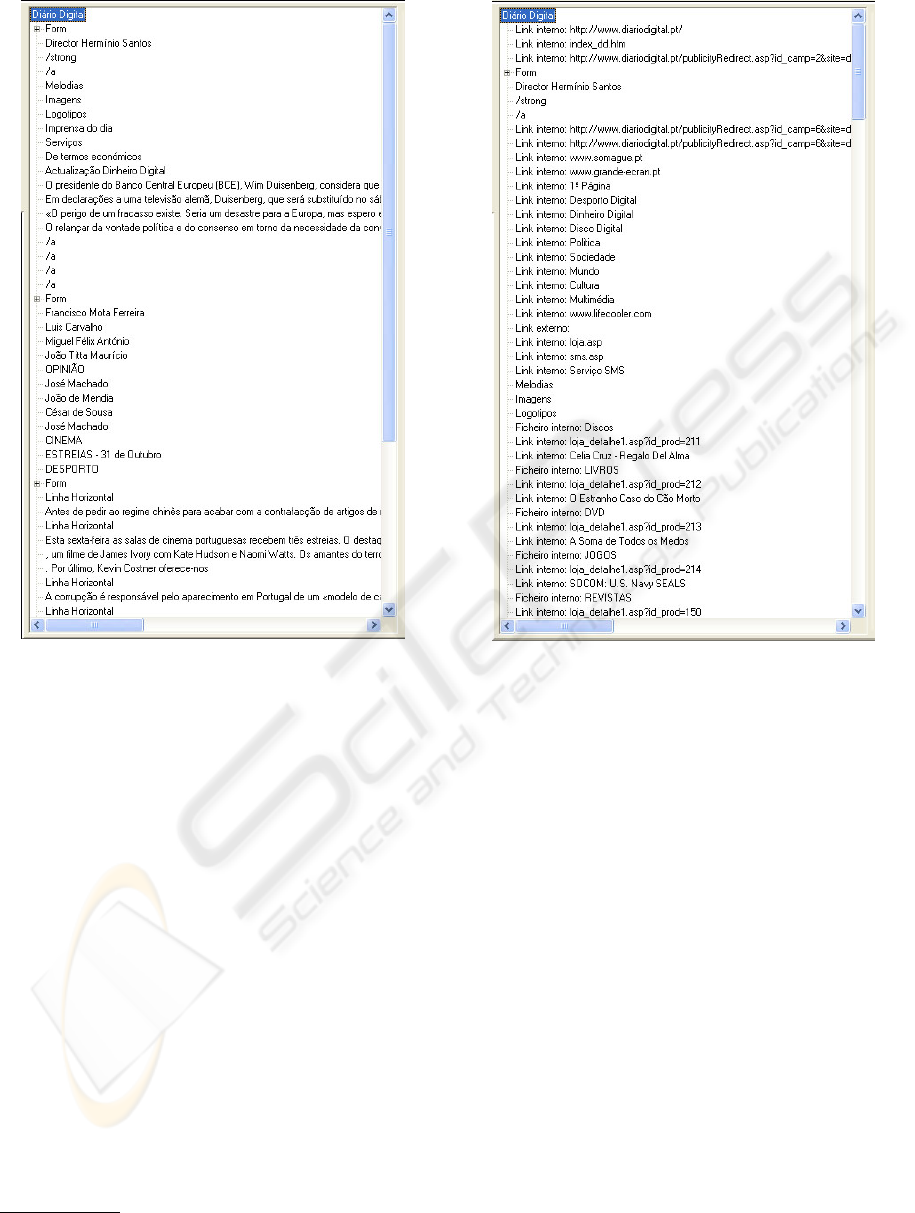

Figure 1

4

shows the text which will be read using this

feature, and figure 2 show the full text of the page as

understood by the browser.

It is clear from the figures that using this feature

provides a much faster access to the real contents of

the web page. In figure 2 the first news item "O pres-

idente do Banco Central..." is not even visible on the

window, whereas in figure 1 it appears very near to

the top. Another clue is the size of the dragging bar

which gives a hint regarding the amount of the text in

both views.

Note that table navigation doesn’t provide the same

functionality since web pages tend to use tables as a

design feature and not a content feature. Therefore

navigating on a table can be cumbersome.

Based on the same assumption the AudioBrowser

allows for the linearization of tables. The reading is

currently row based. In this way the artifacts caused

by tables tend to be eliminated.

The AudioBrowser also provides a third mode

where all the document’s hierarchy is presented. In

this mode the user is presented with a hierarchical tree

where tables, cells and headings are parent nodes of

the tree. The text, links and images are the leaf nodes

4

The text in the images is in Portuguese since the Au-

dioBrowser is currently being developed for a Portuguese

audience only.

ICEIS 2004 - HUMAN-COMPUTER INTERACTION

76

Figure 1: Document View with links removed.

of the tree. This mode gives the user an insight on the

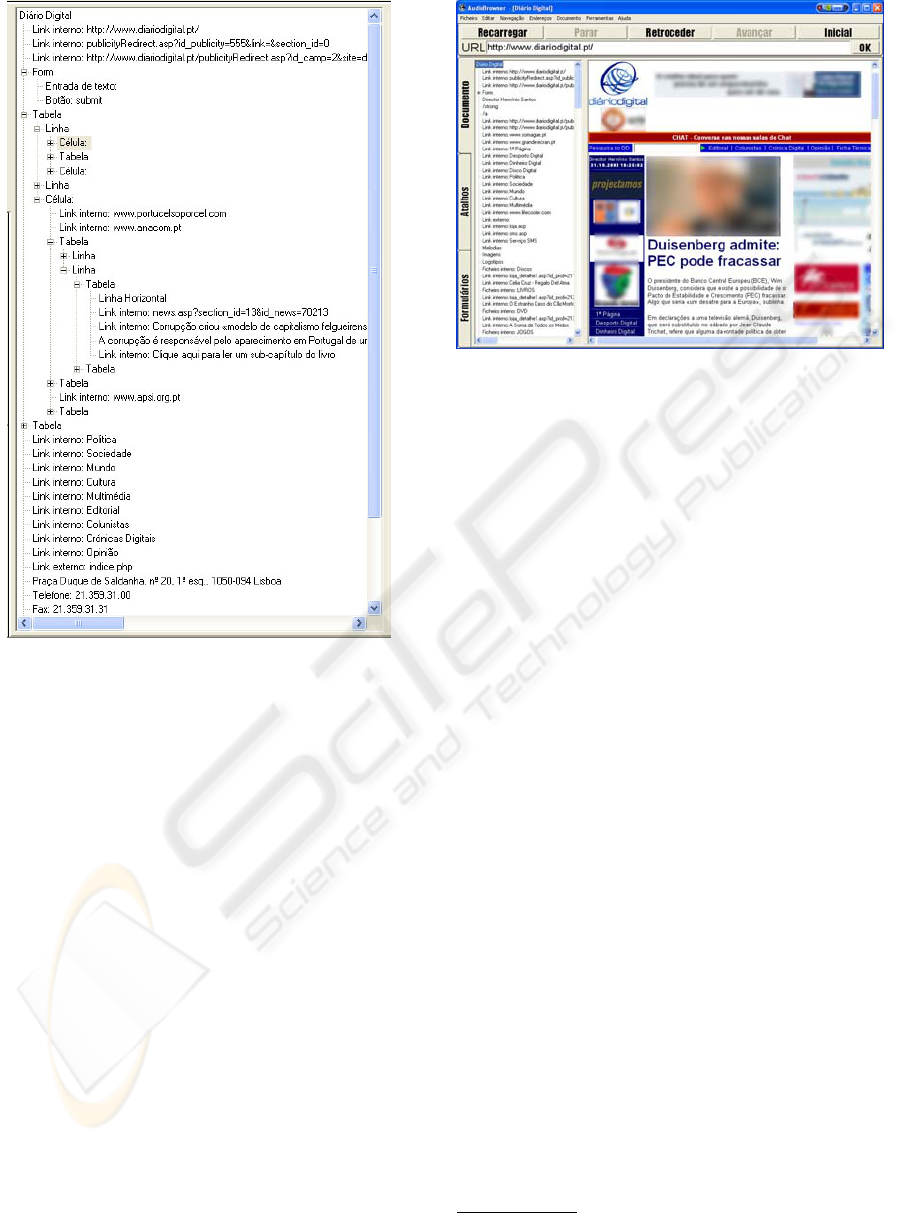

structure of the page, see figure 3.

The AudioBrowser presents any of these views

while at the same time presenting a view of the page

as seen on Internet Explorer, see figure 4

5

. The ability

to present simultaneously multiple views of the page

is useful not only for a visitor of the page, but also for

the web designer as we will point out in section 4.

2.3 Links

In all talking browsers, as well as in screen readers

quick access to links is provided. The AudioBrowser

goes one step further by classifying the links. Links

are classified as:

• external;

• internal;

• anchor;

• an e-mail;

5

The images of individuals and commercial brands were

deliberately blurred.

Figure 2: Normal View of the Document.

• internal files;

• external files.

The notion of an external link is not as clear as one

might think. The semantics of external imply that the

link will lead to a web page outside the group of re-

lated pages under the same base address. The base ad-

dress can be the domain itself, a subdomain, or even

a folder.

For instance in geocities, each user is

granted an area that has as the base address

www.geocities.com/userName. Pages outside this

base address, although in the same domain are

external to the site from a semantic point of view.

Nevertheless, this classification, even if based only

on domains as base addresses, is extremely useful in

some circumstances. Consider a web searching en-

gine such as Google. The internal links represent the

options of the search engine. Once the search has

been performed the external links provide the user

with a quick access to the results.

Long documents with anchors are another example.

In this case the anchors can provide a sort of table of

contents.

ACCESSIBILITY AND VISUALLY IMPAIRED USERS

77

Figure 3: Hierarchical View of the Document

2.4 Bookmarks

Bookmarking a web page is a common procedure

amongst internet users. However the default book-

marking offered in Internet Explorer is not powerful

enough to satisfy fully the visually impaired user, or

as a matter of fact for any kind of user.

The idea behind bookmarking is to allow a user to

save the address of a web page in order to get back

to it latter. This serves a purpose when we consider

small web pages, with little volume of text. When

we consider large pages, with considerable amounts

of text, it may be of use to specify a particular piece

of text.

It may be the case that the user wants to bookmark

not the page itself, but a specific location in the page,

for instance a paragraph. This would allow the user to

stop reading a web page at a particular location, and

then get back to that location latter without having to

start from the beginning of the document again.

Another example where the benefits of bookmark-

ing a specific location of a web page would be of great

use is to allow users to skip text in the beginning of

the document. A significant number of pages have

Figure 4: The AudioBrowser

a fixed structure, where only content varies. As men-

tioned before, it is common to have a left column with

links to sections of the site and other sites. Bookmark-

ing the beginning of the main content area, would al-

low the user to skip the links section when the page is

loaded.

Currently the AudioBrowser seems to be the only

talking browser that has this feature, including com-

patibility with Internet Explorer’s favorites. Jaws

6

,

a popular screen reader, also offers a similar feature

called PlaceMarkers.

2.5 E-mail

E-mail is no longer restricted to text messages: mes-

sages can be composed as a web page. Hence us-

ing the same tools as those used for web browsing

makes perfect sense. The AudioBrowser is capable of

handling e-mail at a basic level, providing the same

set of features that are used for web browsing. The

AudioBrowser attempts to integrate visually impaired

users with regular sighted users, and therefore it uses

the same mailbox as Outlook, hence has access to the

same received messages. The navigation on the mes-

sages is identical to the navigation on a web page,

therefore the interface is already familiar to the user.

3 USER FEEDBACK

In this section we discuss the feedback we got from

users during the project as well as some problems

that arose when attempting to perform usability eval-

uation.

6

Available at http://www.freedomscientific.com/

fs_products/software_jaws.asp

ICEIS 2004 - HUMAN-COMPUTER INTERACTION

78

Visually impaired users were involved in the

project from its early design stages, and helped in

defining the initial requirements for the tool. They

were also involved in analyzing early prototypes of

AudioBrowser.

To evaluate AudioBrowser’s current version we

planned a number of usability tests with its users. This

process turned out more problematic than what we

had initially envisaged. This was partly due to the

typical problem of convincing software developers to

perform usability evaluation, but mainly due to diffi-

culties in setting up the testing sessions.

Performing usability tests with users is always a

difficult and expensive process. We found this even

more so when we are considering visually impaired

users. As point out in (Stevens and Edwards, 1996),

when trying to evaluate assistive technologies diffi-

culties may arise due to a number of factors:

• Variability in the user population — besides the fact

that they will all be visually impaired users, there

is not much more that can be said to characterize

the target audience of the tool (and even that as-

sumption has turned out to be wrong, as it will be

discussed later in this section).

One related problem that we faced had to do with

the variability of use that different users will have

for navigating the web. Due to this, identifying

representative tasks for analysis turned out to be a

problem.

• Absence of alternatives against which to compare

results — in our case this was not a problem since

there are other tools that attempt to help users in

performing similar tasks.

• Absence of a large enough number of test subjects

to attain statistical reliability — this was a major

issue in our case. In fact, we had some difficulty in

finding users willing to participate in the process.

We had access to a reduced number of users and

some reluctance was noticed in participating due to

(self-perceived) lack of technical skills (a “I don’t

know much about computers, so I can’t possibly

help you” kind of attitude). We were, nevertheless,

able to carry out a few interviews, and it is fair to

state that the users that participated did so enthusi-

astically.

One further problem that we faced related to iden-

tifying exactly what was being analyzed in a given

context. The AudioBrowser enables its users to ac-

cess pages on the web. Suppose that, when visiting

some specific page, some usability problem is identi-

fied. How should we decided whether the problem re-

lates to the tool or whether it relates to the page that is

being accessed? For simple (static) pages this might

be easy to decide. For more complex sites, such as

web based applications (where navigation in the site

becomes an issue), it becomes less clear whether the

problem lies with the tool or whether it lies with the

site itself.

Due to these issues, we decided to perform infor-

mal interviews with the available users, in order to as-

sess their level satisfaction with the tool. More formal

usability analysis being left for latter stages.

Even if the reduced number of interviews carried

out does not enable us to reach statistically valid con-

clusions, it enabled us to address some interesting

questions regarding the usability of the AudioBrowser

tool. The analysis addressed two key issues:

• the core concept of the AudioBrowser — a tool tai-

lored specifically to web page reading;

• the implementation of such concept in the current

version of the tool.

Regarding the first issue, the focus on the struc-

ture of the text (as represented by the HTML code),

instead of focusing on the graphical representation

of such text, was clearly validated as an advantage

of the AudioBrowser when compared with traditional

screen readers. Such focus on the structure of the text

enables a reading process more oriented towards the

semantic content of the page (instead of its graphical

representation), and a better navigation over the infor-

mation contents of the page.

Regarding the second issue, the tool was found sat-

isfactory in terms of web navigation. However, its im-

plementation as a stand-alone tool (i.e., a tool that is

not integrated with the remainder assistive technolo-

gies present in the work environment) was found to be

an obstacle to its widespread use by the visually im-

paired community. Aspects such as the use of a sep-

arate speech synthesizer from the one used for inter-

action with the operating systems, create integration

problems of the tool regarding the remaining compu-

tational environment, and can become difficult barri-

ers for users which are less proficient at the techno-

logical level. This is an issue that had not been pre-

viously considered, and that clearly deserves further

consideration.

Besides the planned usability testing, we have also

received reports from regular sighted users who em-

ploy the AudioBrowser to check their own web pages

regarding structure and accessibility. The hierarchi-

cal view of the page provided by the AudioBrowser

allows these users to spot potential accessibility and

syntax problems that would otherwise be hard to dis-

cover. This was a somewhat unexpected application

of the tool, and it stresses the difficulties with identi-

fying the end user population of a software artifact.

ACCESSIBILITY AND VISUALLY IMPAIRED USERS

79

4 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

On this paper we have presented AudioBrowser, a

talking browser that aims at enabling visually im-

paired users to efficiently navigate the web. Audio-

Browser takes advantage of the underlying structure

of the document in order to better present its content,

and is able to present different views of the same doc-

ument enabling the user to choose the view that better

fits its navigational needs at each moment. This fea-

ture is useful not only to visually impaired users, but

also for web designers since it allows them to have a

broader perspective of the construction of the page.

We have received reports of several web designers

that are using the AudioBrowser to this effect.

Features and issues related to talking browsers

were introduced. In this context some of the main

features of the AudioBrowser were described. Focus

was on features that provide increased accessibility.

From a usability point of view the main objection,

as mentioned previously, is the need to switch back

and forth from using the browser to a screen reader,

which is still needed for all the other tasks. This is one

usability problem that was not foreseen neither by the

developers nor the visually impaired people that par-

ticipated on the AudioBrowser project from the very

beginning.

A talking browser and a screen reader are incom-

patible because they both produce speech, and there-

fore they can not be working simultaneously.

However talking browsers have several advantages

over screen readers and should not be put aside. Talk-

ing browsers make it easy to manipulate the web page

and present different views, therefore minimizing the

scanning time for visually impaired users.

Can talking browsers and screen readers be com-

patible? A possible solution for this problem could be

to have the browser not producing any speech at all.

Instead the browser would produce text that would

then be read by the screen reader. It may seem ab-

surd to have a talking browser not talking at all, but

under this approach the browser is in fact "talking"

to the screen reader. In order for this solution to be

successful the process would have to be completely

transparent to the user. To the user the application

would be an enhanced web browser.

A totally different approach would be to have a web

service that provides a subset of the functionality of a

talking browser solution. This requires a proxy based

approach where a web address would be provided.

The page would be transcoded in several views in a

web server, and all those views would be supplied to

a regular browser, for instance using frames. The user

would be able to specify which views would be of in-

terest, and each view, plus the original page, would be

supplied in a separate frame properly identified.

Although this approach requires extra bandwidth

we believe that with the advent of broadband, and

considering that the different views have only text, i.e.

no images, the overhead would be bearable consider-

ing the extra functionality.

Combining a proxy based approach and a talking

browser can provide an enhanced web experience, as

the transcoded web pages may contain special tags

recognized by the talking browser.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research reported in here was supported by

SNRIP (The Portuguese National Secretariat of Re-

habilitation and Integration for the Disabled) under

program CITE 2001, and also FCT (Portuguese Foun-

dation for Science and Technology) and POSI/2001

(Operational Program for the Information Society)

with funds partly awarded by FEDER.

REFERENCES

Fernandes, A. R., Martins, F. M., Paredes, H., and Pereira, J.

(2001). A different approach to real web accessibility.

In Stephanidis, C., editor, Universal Access in H.C.I.,

Proceedings of HCI International 2001, volume 3,

pages 723–727. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Filepp, R., Challenger, J., and Rosu, D. (2002). Improving

the accessibility of aurally rendered html tables. In

Proceedings of the fifth international ACM conference

on Assistive technologies, pages 9–16. ACM Press.

IBM (2000). Web accessibility transcoding system.

http://www.trl.ibm.com/projects/acc_tech/attrans_e.htm.

Jackson-Sanborn, E., Odess-Harnish, K., and Warren,

N. (2002). Website accessibility: A study of ada

compliance. Technical Report Technical Reports

TR-2001-05, University of North Carolina

˝

UChapel

Hill, School of Information and Library Science,

http://ils.unc.edu/ils/research/reports/accessibility.pdf.

Rowan, M., Gregor, P., Sloan, D., and Booth, P. (2000).

Evaluating web resources for disability access. In Pro-

ceedings of ASSETS 2000, pages 13–15. ACM, ACM

Press.

Stevens, R. D. and Edwards, A. D. N. (1996). An approach

to the evaluation of assistive technology. In Proceed-

ings of ASSETS ’96, pages 64–71. ACM, ACM Press.

Sullivan, T. and Matson, R. (2000). Barriers to use: Usabil-

ity andcontent accessibility on the webŠs most popu-

lar sites. In Proceedings on the conference on univer-

sal usability, 2000, pages 139–144. ACM Press.

Zajicek, M., Venetsanopoulos, I., and Morrissey, W. (2000).

Web access for visually impaired people using active

accessibility. In Proc International Ergonomics Asso-

ciation 2000/HFES 2000.

ICEIS 2004 - HUMAN-COMPUTER INTERACTION

80