Protecting People on the Move through

V

IRTUAL PERSONAL SECURITY

Dadong Wan, Anatole V. Gershman

Accenture Technology Labs

161 North Clark Street

Chicago, IL 60601 USA

Abstract. Ensuring personal safety for people on the move is becoming a

heightened priority in today’s uncertain environment. Traditional approaches

are no longer adequate in meeting rising demands in personal security. In this

paper, we describe V

IRTUAL PERSONAL SECURITY, a research prototype that

demonstrates how technologies, such as ubiquitous surveillance cameras,

location-aware PDAs and cell phones, wireless networks, and Web Services can

be brought together to create a virtualized personal security service. By

incorporating automatic service discovery, situated sensing and multimedia

communication, the novel solution provides consumers with increasing

availability, lower cost, and high flexibility. It also creates a new market for

just-in-time micro security services, providing the owners of surveillance

cameras a new revenue stream.

1 Introduction

Today, businesses and individuals alike spend millions of dollars each year on

security services to protect their physical assets, such as factory plants, offices, and

homes. Yet, they take a big risk at neglecting a more important asset -- people. After

the September 11

th

tragedy in the United States, safety concerns, especially personal

safety, have crept into daily news headlines. While governments at the federal, state,

and local levels have made concerted efforts to prevent potential terrorist attacks,

ensuring personal safety is ultimately the individual’s responsibility. That is, each and

every one of us can take more initiatives to ensure the safety of ourselves, especially

by taking advantage of technologies.

When we travel to a new place, or walk through a neighborhood in a familiar city

during late hours, we want to make sure that our personal safety is guarded. At

present, the options available to us are somewhat limited. If we happen to be on a

private property such as a university or corporate campus, or a suburban shopping

mall, and we need to get to our car parked a few blocks away, we might ask the

private security on duty to walk us there. However, this option is not always practical,

especially when we are on the road. As a result, we sometimes take unnecessary risks

by taking the matter into our own hands. With technologies such as surveillance

cameras and mobile devices, we may soon have access to a new solution for personal

security, which will be available anytime, anyplace. In the following sections, we will

Wan D. and V. Gershman A. (2004).

Protecting People on the Move through VIRTUAL PERSONAL SECURITY.

In Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Ubiquitous Computing, pages 139-146

DOI: 10.5220/0002658701390146

Copyright

c

SciTePress

describe such a prototype solution called VIRTUAL PERSONAL SECURITY, including its

underlying technologies, current implementation, and commercial implications.

2 Beyond Passive Surveillance

Surveillance cameras have long been used in both public and private spaces to

monitor what is happening in their surrounding environments [1]. Aside from

providing valuable archival footages for crime solving, studies have shown that the

mere presence of these cameras has positive effects as deterrence for potential crimes

in urban areas [2]. With their rapidly declining costs and increasing concerns about

personal safety, especially in large cities, surveillance cameras are becoming even

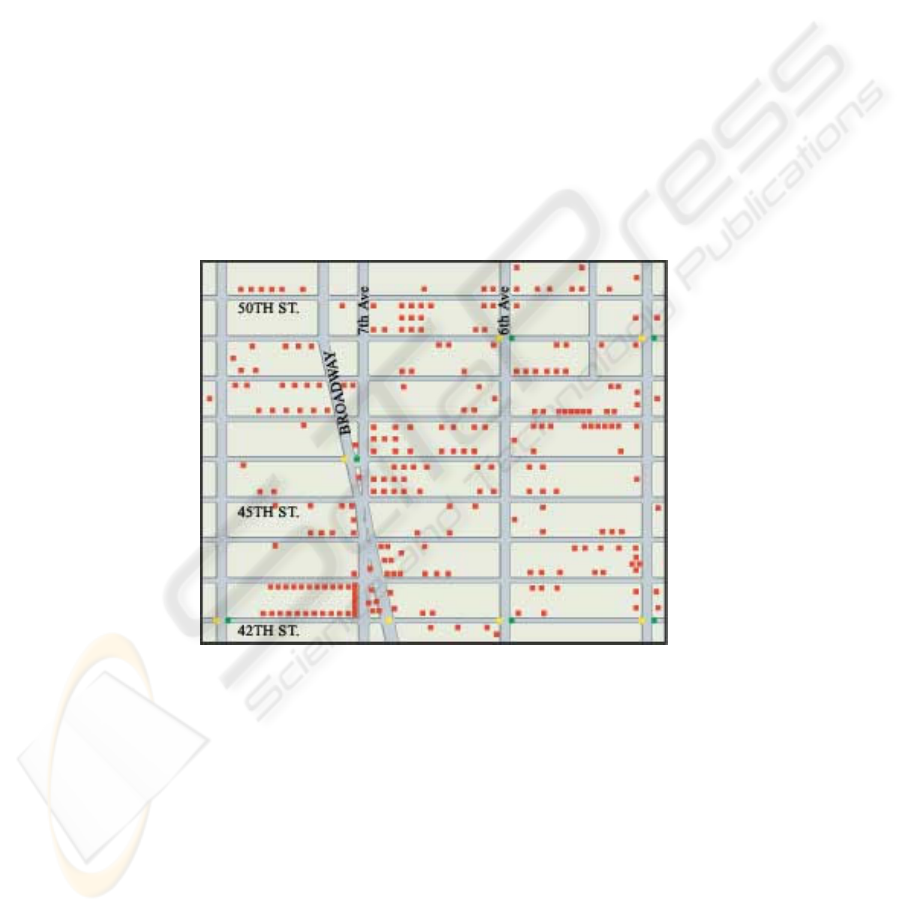

more ubiquitous in recent years. Figure 1, for example, shows the high density of

surveillance cameras in Lower Manhattan [3]. In downtown Chicago, there are on an

average three surveillance cameras in each block [4]. While this omni-presence of

surveillance cameras has raised concerns about individual privacy among civil

libertarians, such a trend is most likely to continue accelerating, especially in light of

rising security concerns among the general public.

Figure 1: Surveillance cameras in Lower Manhattan [3]

Despite their popularity, traditional surveillance cameras have limitations. A vast

majority of these cameras, for example, are based on analog, closed-circuit (CCTV)

technology, which requires special wiring and storage infrastructure. As a result, they

are quite expensive to install and maintain. Furthermore, video streams from these

cameras are stored on analog media such as video tapes, which are difficult to view

and analyze. And finally, these cameras are quite “dumb” in a sense that they don’t

know who they are, and what they are pointing. However, these problems are

disappearing with a new generation of surveillance cameras, which are essentially

140

interactive Web cams. These cameras come with built-in Web servers, and capable of

originating real-time stream videos over the Internet. With this new capability, they

can be used beyond just passive surveillance. As they become more ubiquitous, these

cameras may be used to actively monitor any moving target in the physical world,

such as a person on the move, by sequentially “turning on” the cameras along with the

path, provided that we know the real-time location of the target, and the direction to

which the target is moving.

3 Location-aware Mobile Devices

Another important recent technology trend is the increasing popularity of mobile

devices, including cell phones and PDAs. In many parts of the world, such as Europe

and Asia, cell phones are the most omni-present technology around. The new

generation of cell phones is full-fledged computing devices, featuring built-in cameras

and color displays, as well as multimedia and location awareness. It is interesting to

note that the earliest use of cell phones is for personal safety and emergency purposes.

Yet, until recently when we make a 911 emergency call, the recipient has no way of

determining the exact location of the caller. With the Enhanced 911 (E911) mandate

from the US federal government [5], cell phone carriers in the US are required to

provide locationing capabilities by the year 2004. In other countries such as South

Korea and Japan where mobile phones are more advanced, such capabilities are

already widely available.

At the same time, PDAs are undergoing a different kind of evolution, moving from

being a computing device to a communication device. Newer Pocket PC models, for

example, feature powerful processors and built-in 802.11b (i.e., Wi-Fi) – the fastest

growing wireless network technology in the US. The use of Wi-Fi also enables PDAs

to become location-aware. With the steady improvement of Voice over IP (VoIP),

PDAs are also increasingly used for voice communication. The convergence of cell

phones and PDAs has led to hybrid devices like Handspring’s Treo and T-Mobile

PocketPC phone.

4 Toward VIRTUAL PERSONAL SECURITY

Imagine this scenario: you get off from a late meeting at your client site, and you have

to walk to your car parked about half a mile away. Fearful of walking alone in the

dark, you pull out your iPaq and say, “Personal Security, please.” The application

responds by looking up in an online registry of security service providers, and

selecting the most appropriate one based upon your preference in quality, trust,

pricing, and the provider’s current availability. Once the connection is established, the

remote security agent turns his full attention on to you. Since your iPaq knows where

you are at the very moment, the application uses this information to locate and “turn

on” the surveillance cameras in your area. Sitting in front of his multi-monitor service

desk, the security agent can see from multiple angles about what is happening in your

141

immediate environment. If you tell him which direction you’re heading, he can

“preview” the path by checking on the surveillance cameras along the way to make

sure it is safe to proceed. If not, he may suggest an alternate route. A service like this

may last between five minutes and half an hour or longer. And it can be called upon

anytime, anywhere.

The concept of

VIRTUAL PERSONAL SECURITY, as depicted here, is centered on the

keyword virtual, which implies that the service provider and its recipient don’t have

to be physically together in the same place at the same time. Instead, the co-presence

is created by the seamless integration of three different technologies: location-aware

mobile devices, fixed-location, Web-enabled surveillance cameras, and Web Services.

The mobile device (i.e., PDA or cell phone) is the real-time personal locator. The

exact locationing mechanism and the accuracy may vary depending on the specific

type of devices being used. For example, most cell phones use a combination of GPS

and cell-based triangulation, and their accuracy ranges from 5 to 50 meters. Most

PDAs, in contrast, use 802.11 signals to pinpoint the location of the device holder. Its

accuracy can reach as high as one meter in outdoor settings [6]. Besides locationing,

the mobile device also serves as the primary interface between the user and the

service provider. To that end, it supports wireless voice and data. The voice channel is

important in that it provides the remote service provider auditory clues (i.e., “ears”) to

the user environment.

The surveillance camera is the situated “eyes” for the security service provider,

allowing them to see remotely what is happening in real-time. Since the recipient is

constantly moving, the key here is to be able to quickly determine and select which

cameras to view. Since the application knows the real-time location of the recipient,

and that each surveillance camera also publishes its own coordinates and orientation,

the application can automatically determine which cameras are relevant at any given

moment. As the recipient moves, the views are shifted from one camera to another.

Depending on the camera density in the area where the recipient happens to be, and

the service provider selected, multiple camera views can be supported at the same

time. This ensures that most or all directions of the scene are covered.

The third enabling technology is Web Services, or more specifically, the Universal

Description, Discovery, and Integration (UDDI) [7]. In a nutshell, Web services are a

set of open standards (e.g., XML, SOAP, UDDI) that enable applications of different

sources (e.g., languages, platforms, and organizations) to automatically find, link and

interact with one another over the Internet, sharing data and performing tasks, all

without human intervention. As the name implies, UDDI provides a standard

framework for application publishing, discovery, and dynamic integration. At its core

is a registry that contains detailed descriptions of businesses and services. UDDI

specifies an API that allows programmatic publishing and searching in this registry.

Underlying the virtual personal security application are two UDDI registries:

surveillance cameras and security service providers. Each geo-coded surveillance

camera has an entry in the first registry, and each entry contains information like

camera type, coordinates, orientation, owner, and possibly price. Each security service

provider maintains an entry in the second registry, which provides detailed

specifications about the service, including current availability, price, and interface

details required to invoke the service. Given the user’s requirements and location, the

application makes use of the standard UDDI API to discover the right service

142

provider and closest surveillance cameras. Figure 2 provides a summary of these key

components of

VIRTUAL PERSONAL SECURITY.

Figure 2. Components of VIRTUAL PERSONAL SECURITY

5 The Prototype

To demonstrate the conceptual viability and the technical feasibility of VIRTUAL

PERSONAL SECURITY

, we built an initial research prototype. For the ease of control,

we selected an indoor environment, i.e., the 36

th

floor of our office in downtown

Chicago. On this floor, we installed 33 Axis 2100 Web cams that point at various

sections of the floor: entrances, hallways, enclosed offices, break areas, and meeting

rooms. The floor is also covered with an 802.11 wireless local area network. The

mobile device we use is iPAQ 3860 running Microsoft PocketPC operating system.

The iPAQ is equipped with a dual-slot extension sleeve, which is used for Orinoco Wi

Fi card and Veo Travel Photo camera, respectively. To provide two-way voice over

the IP network on the iPAQ, we use Running Voice IP from Pocket Presence. The

locationing function is built upon the Ekahau 802.11b locationing engine [6], which is

capable of offering up to one-meter accuracy.

The application consists of three modules: user, provider, and brokering, each is

running on a separate machine that is connected to the same local area network. The

user application runs on the iPAQ the user carries around. It is the primary interface

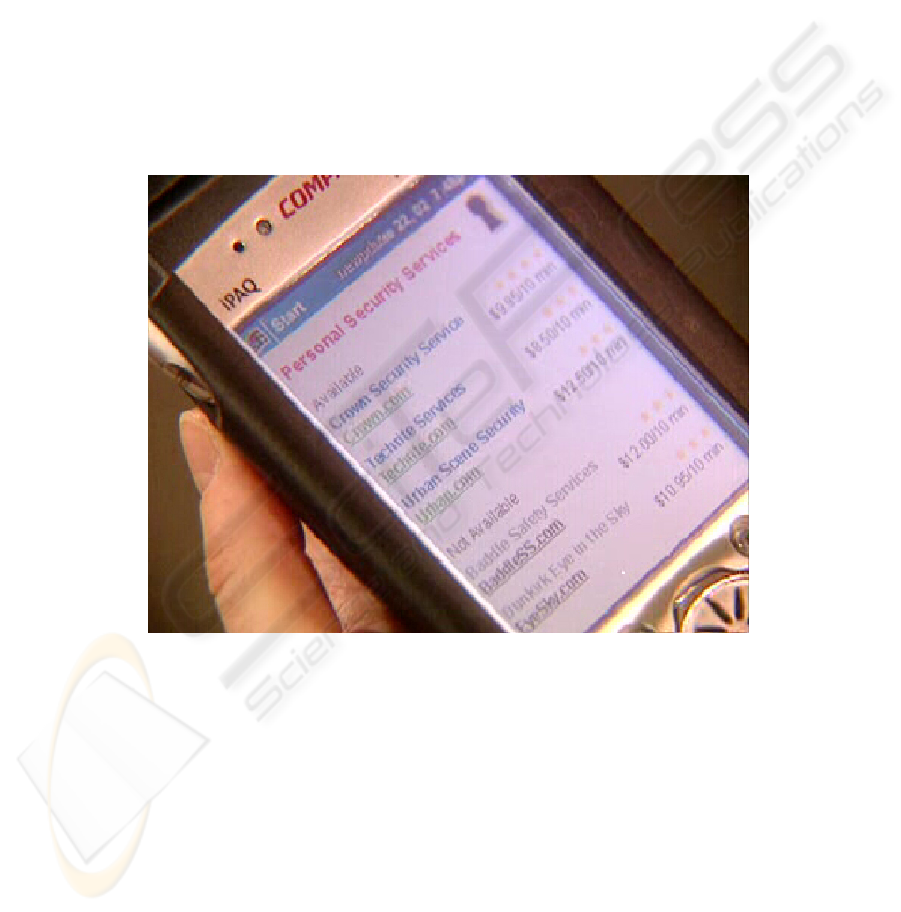

between the user and the security service provider. Figure 3 shows a sample user

screen. After the user makes a request for service, the control is passed over to the

brokering module, which maintains two UDDI registries: one for all the surveillance

cameras on the floor and another for the list of service providers available. For the

prototype, the first registry contains 33 entries, one for each surveillance camera on

Security Service Providers

Brokering

Application

Internet

UDDI Registry:

Geo-coded

Surveillance

Cameras

UDDI Registry:

Security Service

Providers

Users

User Application

Provider Application

Internet

143

the floor. The second registry contains half a dozen of service providers. The Web

services interface is implemented using Microsoft UDDI Server SDK.

As soon as a right service provider is found, a connection is automatically made

between the user application and the provider application. Figure 4 shows a view of

the provider application, which includes a three-monitor setup. The center screen

shows the real-time user location on a map, along with the view from the Veo camera

attached to the iPAQ. The two side screens provide the views from two surveillance

cameras nearby the user. The maps next to them show where those cameras are

located. Collectively, these three different camera views provide the remote security

agent a good sense of what is happening in the user surrounding environment. In the

real-world setting, a professional security company is most likely to support an even

larger number of views. In the event of an emergency, an alarm can be locally

sounded, either by the user or remotely by the security agent, whoever discerns the

situation first. Local help from law enforcement agencies could be immediately

notified and dispatched when necessary.

Figure 3. A sample screen from the user application running on an HP iPAQ 3860.

6 Implications and Discussions

VIRTUAL PERSONAL SECURITY is an early stage conceptual prototype that

demonstrates how ubiquitous technologies, including surveillance cameras, location

aware mobile devices, the Internet and Web Services, can be brought together to

create a new alternative for personal safety, especially in situations where a physical

security escort is either unavailable or too expensive. Our approach is novel in that it

144

combines the best features of the two forms of ubiquitous computing: mobile and

embedded. Being mobile, devices like PDAs and cell phones provide a convenient

delivery channel for services for people on the move. They also serve as a good

location sensor for tracking the real-time location of the device holder. However,

these devices offer limited vision – perhaps the most important sensory data for

security applications -- in part due to their limited bandwidth and power. On the other

hand, surveillance cameras are rich sensors embedded in our environments dedicated

to safety/security purposes. They provide high-fidelity views of the area being

covered. Their locations are not only known but often strategic. Furthermore, they are

becoming increasingly pervasive and Web enabled, which makes them accessible

anywhere. The combination of the two enables rich sensing of the user environment,

and therefore provides sufficient context for viable security services.

Figure 4. An example view for the security service provider’s application.

We envision a service like VIRTUAL PERSONAL SECURITY to be initially offered in

closed-end spaces like university campuses and private parking lots or structures.

With Web enabled surveillance cameras, wireless broadband, and location aware

devices become more ubiquitous, we expect that such a service eventually becomes

feasible on a massive scale. When this happens, a new marketplace for virtual

personal security will emerge. Today, surveillance cameras, which are owned by

different public and private entities, are severely under-utilized resources. In this new

marketplace, these cameras can be made available to licensed security companies as

extra eyes to ensure personal security. For the owners of surveillance cameras, this

represents a new source of revenue streams. Security firms also do not need to spend

valuable resources to install a vast surveillance infrastructure. Instead, they can take

145

advantage of a distributed infrastructure that is already in place and, as a result, offer

the service at an affordable level.

To make the concept of

VIRTUAL PERSONAL SECURITY a reality on a large scale,

however, we will still need to overcome three key technological barriers. First,

surveillance cameras must continue to become cheaper, more powerful, and perhaps

most importantly, truly ubiquitous. While today they are already pervasive in large

cities, it may still take some time before they cover every street corner in every city

neighborhood. Second, surveillance cameras must become more open, and Web

enabled. In other words, real-time video streams from these cameras need to be

available over the Internet so that they are viewable anywhere. And finally, the

locationing capabilities of mobile devices must also improve. While the 50-meter

requirement from the US federal government may be adequate to pinpoint a 911

emergency caller, it is too coarse for locating closest surveillance cameras, especially

when the camera density is high. Despite these hurdles, however, we already witness

early signs of progress made on all three fronts. Thus, we believe that the

technological infrastructure required for realizing the vision of

VIRTUAL PERSONAL

SECURITY

will soon be in place.

7 Conclusions and Future Work

In this paper, we presented a novel prototype application called VIRTUAL PERSONAL

SECURITY, which aims to monitor and protect people on the move, just like what ADT

does to property security. One main premise of our approach is that such a service can

be offered by using mostly existing infrastructure, such as the Internet. To that end, it

brings together a number of emerging technologies, including Web-enabled

surveillance cameras, location aware mobile devices, and Web Services. While our

initial prototype is implemented in a somewhat limited, artificial indoor setting, it

clearly demonstrates the viability of the concept and its technical feasibility.

Currently, we are in an active discussion with a major university in Chicago to pilot

the concept on their campus, where 802.11b network is already in place. As

locationing capabilities become more readily available on cell phones in the US, we

also plan to implement another version of the prototype using cell phones.

References

1. David Brin, The Transparent Society: Will Technology Force Us to Choose between

Privacy and Freedom? Perseus Books, Reading, MA. 1999.

2.

Jeffrey Rosen. A Watchful State. The New York Times Magazine. October 7,

2001.

3. Dan Farmer and Charles C. Mann. Surveillance Nation. Technology Review (April,

2003), pp. 34-43.

4. Chip East. Watching you, Watching me in NYC. MSNBC News. April 8, 2003.

5. For further information on E911, see www.fcc.gov/911/enhanced/

6. Ekahu. Accurate Location in Wireless Networks. See www.ekahau.com/technology.

7. For more information on UDDI, see www.uddi.org and www.webservices.org.

8. Steve Mann, "Wearable computing: A first step toward personal imaging," IEEE

Computer, vol. 30, no. 2, Feb 1997.

146