Familialism and financial resources in old age. Setting

the scene for the provision of care in Portugal

Alexandra Lopes

London School of Economics

Department of Social Policy. LSE Health and Social Care

Houghton Street. London WC2A 2AE. United Kingdom

Abstract. The paper examines some trends in the living arrangements and in

the living conditions of the Portuguese elderly . The analysis draws on panel

data from the European Community Household Panel and provides a

sociological characterization of the living realities of the Portuguese elderly in

order to ground in empirical evidence the discussion on the interest and

viability of tele-care in the Portuguese context. The main argument of the paper

is that in a society still strongly marked by traits of familialism, all mechanisms

that are based on the idea of the elderly remaining in their homes are of

potential interest in the sense that they can complement and improve the quality

of the care provided by families. The second argument of the paper addresses

the issue of the financial conditions of the Portuguese elderly and raises

awareness for the limitations of any market-based solutions as potentially

triggering further inequalities within the care system.

1 Introduction

Despite the erosion of the traditional modes of functioning of the Portuguese society,

Portugal can be argued to remain a strongly familialist system in the ways it organises

for the provision of welfare. This trait becomes particularly clear if analysed from a

cross-national comparative perspective. By familialism one means a system of

welfare provision where the families and the households are taken as the primary

locus for social aid, but more than that, where families are assumed not to fail when

performing that role.

The labelling of the Portuguese system as a familialist system shapes quite

considerably the debate about the provision of care for the elderly in this country.

While in other European countries the debate on care for the elderly often involves

taking as a starting point the absence of family resources and in fact a majority of

elderly living alone, in Portugal, similarly to other South European countries, that

same debate has to take as a starting point the prevalence of traits of familialism in the

ways elderly people organise their lives, namely the comparatively higher incidence

of cohabitation between generations.

This paper aims at giving a contribution to the debate on the solutions for the

provision of care for the elderly, by analysing the living arrangements and the living

conditions of the Portuguese elderly. The focus is on the presence of strong familialist

Lopes A. (2004).

Familialism and financial resources in old age. Setting the scene for the provision of care in Portugal.

In Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Tele-Care and Collaborative Virtual Communities in Elderly Care, pages 119-135

DOI: 10.5220/0002665001190135

Copyright

c

SciTePress

traits in the ways the Portuguese elderly organise their lives. The argument that flows

along the paper is that designing solutions for the provision of care in Portugal has to

take into account those traits. In that sense, it is reasonable to expect that developing

solutions that facilitate the lives of families as welfare providers may tackle one of the

main problems related to care for the elderly in Portugal. Families are still there and

are still a relevant welfare provider. The fact that they are experiencing increasing

difficulties in performing that role should signal the need to invest in policies that

alleviate that burden by promoting simultaneously a better quality of life both for the

elderly and for their carers. The use of new technologies and in particular of long-

distance assistance mechanisms can have a particularly fertile ground for

implementation in the Portuguese context.

This question however has another side: the side of the financial implications of

the solutions to be implemented. It is legitimate to ask who will pay for the

application of home-based technologies to the provision of care for the elderly. What

this paper tries to discuss is the impossibility of putting the financial burden on the

elderly or on the families. By analysing the financial situation of the Portuguese

elderly population and of their households the paper will demonstrate how generalised

is the lack of financial resources to cope with any market-based solution. This has

immediate and obvious implications for the state as welfare provider that can not be

disregarded when debating this topic.

The paper is organised in four parts. In the first part it puts forward the key

arguments underlying the analysis and identifies the core research questions being

addressed. In the second part we find a brief description of the methods and data used

in the analysis. This paper draws on data from the European Community Household

Panel. The third part is the core of the paper and lays down the main findings of the

analysis. It starts with some considerations on the living arrangements of the elderly

followed by some analysis of the engagement of the Portuguese society in caring after

the elderly. Both components of the discussion will support the argument about the

importance of a familialist approach to the provision of care for the elderly in the

Portuguese context. After that it moves on to some analysis of the financial situation

of the Portuguese elderly and their households trying to capture, even if broadly, some

indicators about the availability of financial resources in old age and about the

feasibility of market-based solution within the context of the Portuguese society. The

fourth and last part of the paper brings together some concluding remarks about the

findings highlighting the policy implications of those when debating the introduction

of new mechanisms of provision of care for the elderly in Portugal.

2 Arguments

In a context of increasing demands for caring services and solutions but, at the same

time, of increasing constraints on the financial ability of the states to meet those

needs, it has been argued that the search for alternative mechanisms of care provision

that maximize the permanence of the elder person at home will be one of the most

feasible ways to address the overall issue of care for the elderly in the near future [5].

That will respond not only to the limitations of resources available by developing

solutions that can be potentially cheaper than institutional care, but also to the

120

demands for better quality of care and better quality of life in old age. Among these

alternative mechanisms one can discuss the interest of tele-care solutions.

The interest of a paper on living arrangements and living conditions of the elderly

in a workshop about tele-care is grounded in the fact that if we are to stand for

mechanisms of care that are based on the elderly staying in their homes, we need to

know where they are living, what are their living arrangements and their living

conditions.

Living arrangements are one of the most important dimensions of quality of life

and well being in old age. They are strongly correlated with the availability of family

care, as well as social and economic support, therefore determining the ways the

elderly will tackle old age related needs. It has been widely recognized that in order to

plan care services it is very important to have information on patterns of living

arrangements among the elderly, in order to better assess not only the nature of the

needs of these but also the existing resources to tackle those needs [3] [7].

This paper argues that mechanisms of care provision such as tele-care are

particularly interesting in the Portuguese context because of the persisting traits of

familialism that characterize the living arrangements of the elderly in our society.

Families remain the main source of support in old age and therefore we are still in

time to structure the provision of care to elderly taking the family as the starting point.

If the traditional family support is under constraint and if families are experiencing

more and more difficulties in acting as welfare providers it is largely because they are

not being targeted as welfare providers. The dissemination of mechanisms that can

help families deliver care and that can make it less burdensome to juggle care and

paid work are argued to fit the sociological characteristics of the elderly population in

Portugal.

However, designing solutions for the delivery of care is not dependent solely on

the sociological profile of the living arrangements of the elderly people. It must take

into account other factors, among which the availability of financial resources in old

age. The paper tries to provide some evidence on the disadvantaged financial situation

of the majority of old age people in Portugal and on the limitations that represents in

terms of policy design. Any type of alternative solution to institutionalised care will

necessarily involve state funding based programs. Any other approach would mean

severe equity problems that would in any case respond to market imperatives but fail

to address the main issue of increasing needs for care among the elderly. Provision of

tele-care and other long-distance assisted care mechanisms has to consider the

financial realities of the elderly and has to be thought of from the perspective of cost-

effectiveness when the state is the likely fund provider.

3 Methods and data

The paper uses data from the European Community Household Panel (ECHP). The

ECHP is a longitudinal panel covering the EU population, which commenced in 1994

and follows up its sample members annually. The ECHP has been interrupted after its

8

th

wave. At the time the analysis was carried out there had been released the 5 first

waves of the panel (1994 to 1998). In the first 2 waves the panel did not cover the 15

EU member states (Austria joined in the second wave, in 1995, and Sweden and

121

Finland in 1996). Also, there were some problems of reliability with the data recorded

for Luxembourg. In our research we only consider the national samples of 11

countries: Germany, Denmark, Netherlands, Belgium, France, United Kingdom,

Ireland, Italy, Greece, Spain and Portugal.

The ECHP is the first cross-national panel survey that has been administered in a

comparable way across the EU, to households rather than to individuals. It contains

data on personal characteristics of all the members of each household, at the same

time that retains data for the household as a unit. And these are the main advantages

of the ECHP compared to any other survey available: because it is a household survey

it collects information on all members of respondent households, which is particularly

useful in the analysis of living arrangements. Because the same questions were asked

in each country, the results are directly comparable overcoming the most common

problems of harmonization of data in cross-country analysis. In addition, because it is

a panel, it allows for some reliable analysis of trends over time, namely for the

analysis of changes in living arrangements and of the factors that trigger those

changes. Finally it is a relatively large panel compared to some other datasets. Wave 1

contains information on more than 9000 males and over 12000 females aged 65 or

over.

The paper draws on some descriptive analysis of data from the last wave available

(1998). At the time the paper was written the analysis of the longitudinal dimension of

the panel was in progress and therefore still not available for dissemination. It was

considered that the results to include in the paper should refer to the closest point in

time, therefore focusing on 1998. Some glimpses of dynamic analysis are included in

the paper and when that is the case data from previous waves are recovered.

The findings of the paper are organized in two main parts. The first part focuses on

the characteristics of the living arrangements of the elderly people in Portugal

highlighting the permanence of traits of familialism and setting the scene for the

implementation of policies of care provision from a sociological perspective. The

second part focuses on the analysis of the financial conditions of the elderly and

particularly on some poverty analysis.

The numerical findings include some multivariate analysis with the estimation of

some models for the likelihood of some specific types of living arrangements. This

however responds more to an exercise of synthesis than to any real attempt to model

realities. Along the paper, and for clarification purposes, information about the

variables used for the analysis and the specific approaches developed will be put

forward.

4 Findings

The argument put forward in this paper is two folded. On one hand it is argued that

the permanence of strong traits of familialism in the ways the Portuguese elderly

organise their lives makes it necessary to consider the family as a unit of welfare

provision in any discussion about mechanisms of care. On the other hand it is argued

that both the elderly and their families do not have the financial resources to purchase

those mechanisms if they are implemented on a market-basis provision.

122

The section on findings is therefore organised according to these two axis. Firstly we

will find some evidence about the importance of familialism in the living strategies of

the Portuguese elderly. This is done by analysing their living arrangements but also

by analysing the nature of the engagement in caring after the elderly by the

Portuguese families. Secondly we will find some evidence about the financial

conditions of the elderly and of their households.

The living arrangements of the Portuguese elderly

Where and with whom are the Portuguese elderly living?

The living arrangements of the elderly were classified according to a six categories

typology, which is the result of the combination of theoretical criteria and data

availability. The categories are as follows:

− living alone

− living with spouse

− living with spouse and adult children

− living just with adult children

− living in complex household with dependent children

− living in other complex household without dependent children

Different studies use different typologies, most of the times depending on the

research questions being addressed. As for the first 4 categories they are self-

explanatory. In this typology we would highlight the meaning of the last 2 categories.

First, the term “complex household” was chosen to designate a household structure

that is more complex than the nuclear family, either because involving the

cohabitation of more than 2 generations - which is often the case of the complex

households with dependent children, meaning that the elderly is living with at least

one adult child, his or her spouse and grandchildren – or because involving bonds

among the household members different from parenthood – some examples are

daughters in law or other relatives such as brother/sister.

As for the observed crude differences among countries our attention is drawn

immediately to the South European cluster (to a certain extent followed by Ireland,

but less clearly). It is in these countries that one seems to observe a clear trait of

familialism reproduced in the elderly people’s lives in the form of a relatively high

share of individuals living in some kind of complex extended household. It is also in

these countries that one finds the lowest shares of elderly living alone as well as signs

of another well documented phenomenon in familialist systems which is the late

departure from the parental home by the younger cohorts reflected in a

proportionately higher incidence of adult children/parents cohabitation [2].

Focusing on the Portuguese elderly sub sample, we have tried to identify the

profiles of the elderly according to their living arrangements. The interest of this

analysis is more than merely descriptive. Understanding the characteristics of the

different living arrangements from the perspective of the socio-demographic

characteristics of the elderly should allow for some preliminary considerations on the

potential factors associated to each living arrangement and on the implications of that

in terms of policy design.

123

Table 2 below summarizes data on a set of variables taken as descriptors of the

different living arrangements considered. In the next few paragraphs we will put

forward some considerations on the meanings of those data.

Several studies have shown the strong association between gender and living

arrangements in old age, as well as with the patterns of change in living arrangements

as age progresses once reached old age. One should note that, at least partially, these

features should not be imputed to any specific institutional or cultural milieu in the

Table 1. Cross–sectional frequencies for the living arrangements of the elderly people in 11

ECHP countries, in 1994 and in 1998 (row percentages)

Living arrangements

Countries

Year

Valid

n

Alone

With

spouse

With spouse

and adult

children

With adult

children

In complex

household

1

1994 1626 38.1 52.0 5.7 a) 2.2 Germany

1998 1644 42.2 48.6 3.6 a) 3.9

1994 557 39.4 58.4 a) a) - Denmark

1998 558 48.2 50.0 a) a) a)

1994 1039 37.5 56.4 4.4 a) - Netherlands

1998 984 43.5 52.6 a) a) -

1994 731 41.4 45.6 7.2 a) a) Belgium

1998 740 45.9 43.0 4.2 a) 4.3

1994 1590 33.0 54.3 6.3 3.9 2.4 France

1998 1614 37.7 49.1 4.3 4.0 4.8

1994 1423 40.4 50.5 4.3 3.3 a) UK

1998 1438 45.9 44.1 2.8 3.4 3.7

1994 657 37.1 34.0 15.4 8.4 4.8 Ireland

1998 684 40.6 31.0 9.3 8.4 10.7

1994 2027 27.8 45.5 11.8 4.3 10.6 Italy

1998 2019 31.9 39.3 9.0 5.2 14.7

1994 1336 21.5 46.4 10.4 4.0 17.6 Greece

1998 1372 27.4 41.1 7.0 4.5 20.0

1994 1630 16.7 41.4 19.4 7.1 15.4 Spain

1998 1709 19.4 35.9 15.4 7.7 21.5

1994 1287 21.0 44.7 14.1 5.9 14.1 Portugal

1998 1236 26.9 38.1 9.5 5.1 20.3

Source: ECHP, waves 1 and 5 (1994 and 1998)

Obs. Cases are weighted

Notes:

1)

given the very low frequencies observed in the 2 categories defined for complex

households (with or without dependent children), it was considered that the aggregation of

both categories would bear more significance for the cross-national comparison. If not, the

small numbers observed for those categories would make it impossible to display any data

at all for a large number of countries.

a)

the frequencies observed are below 40 (non weighted cases) (Eurostat regulations on

data presentation determine that we do not present the respective proportions for those

categories)

124

sense that they are often the “natural” consequence of the demographic behaviour of

older cohorts.

It is not surprising to find in that respect that among the elderly living alone a bit

more than 75% are females. This is undoubtedly related to the fact that women have a

higher life expectancy than men and tend to be because of that proportionately more

exposed to widowhood, adding to the fact that women tend to marry older men,

reinforcing the effect of their higher life expectancy.

Although this is a far too well recognised trait of the living arrangements of the

elderly, it is important to highlight it once more from the perspective of the

implications of gendered patterns of living arrangements for policy design. If one

looks at the distribution within each gender category, it should be almost self-evident

the importance of recognising that more than 60% of the male elderly are living with

a spouse, while among females that group hardly reaches 40%. When it comes to

discussing the provision of care for the elderly, it becomes evident that for males the

most likely provider will be a spouse, frequently an elderly herself. As for females,

that likelihood is significantly reduced, while it increases the likelihood of living

alone and therefore the exposure to the risk of absence of an informal carer if in need

and the need to resource to descendents or other kin. We will come back to this issue,

but what the gender divide seems to suggest is that the issue of living arrangements is

Table 2. Individual-based variables describing the living arrangements of the Portuguese

elderly, in 1998 (column percentages)

Living arrangement

Individual-based variables

Alone Couple Couple

with

adult

children

With

adult

children

Complex

household

with dep.

children

Complex

household

without

dep.

children

Male 23.8 57.5 66.7 18.9 30.6 30.7 Gender

Female 76.2 42.5 33.3 81.1 69.4 69.3

65-69 4.9 9.5 15.6 12.2 9.6 9.3

70-74 31.6 45.4 47.5 28.9 36.9 32.6

75-79 31.6 28.5 26.2 20.0 28.0 23.7

80-84 18.9 12.4 7.1 23.3 14.6 16.7

Age

group

85+ 13.1 4.2 3.5 15.6 10.8 17.7

Married - 96.1 99.3 - 29.3 30.7

Divorced/separated 2.7 - - - 1.9 3.3

Widowed 87.1 1.8 - 97.8 66.2 43.3

Marital

status

Never married 9.2 1.9 - - 2.5 22.8

Yes, severely 24.0 25.1 30.5 26.7 33.8 26.4

Yes, to some

extent

25.2 25.1 17.0 23.3 17.8 24.1

Hampered

in daily

activities

No 50.9 49.8 52.5 50.0 48.4 49.5

Yes, after children 1.2 1.5 - 2.2 12.7 -

Yes, after adult - 4.2 9.9 10.0 2.2 7.5

Engaged

in caring

after

someone

No 98.5 94.3 90.1 87.8 85.4 92.0

Source: ECHP, wave 5 (1998)

125

largely an issue for females. Women are far more often confronted with changes in

living arrangements here reflected in a larger variety of living forms than men.

The same way as gender, age seems to be a significant discriminator element of

living arrangements in later life. We would highlight in particular the age distribution

among those living alone. It is very relevant that 95% of those living alone are 70 or

more years old (undoubtedly an effect of their exposure to widowhood), and that a bit

more than 30% are actually over 80. If one accepts that the likelihood of developing

age-related needs increases with age, this group of old people living alone must be a

special target in terms of policy design. However, and from a comparative

perspective, the age distributions of the other living arrangements also show how

relevant is the presence of the very old elderly in the households where extended

family resources are available (around 30% among the 2 types of complex

households).

The gendered divide mentioned above is largely reinforced by age, which shows as

referred before the effect of the demographic behaviour of older cohorts, namely in

terms of male and female life expectancy. The graphs that follow provide a very

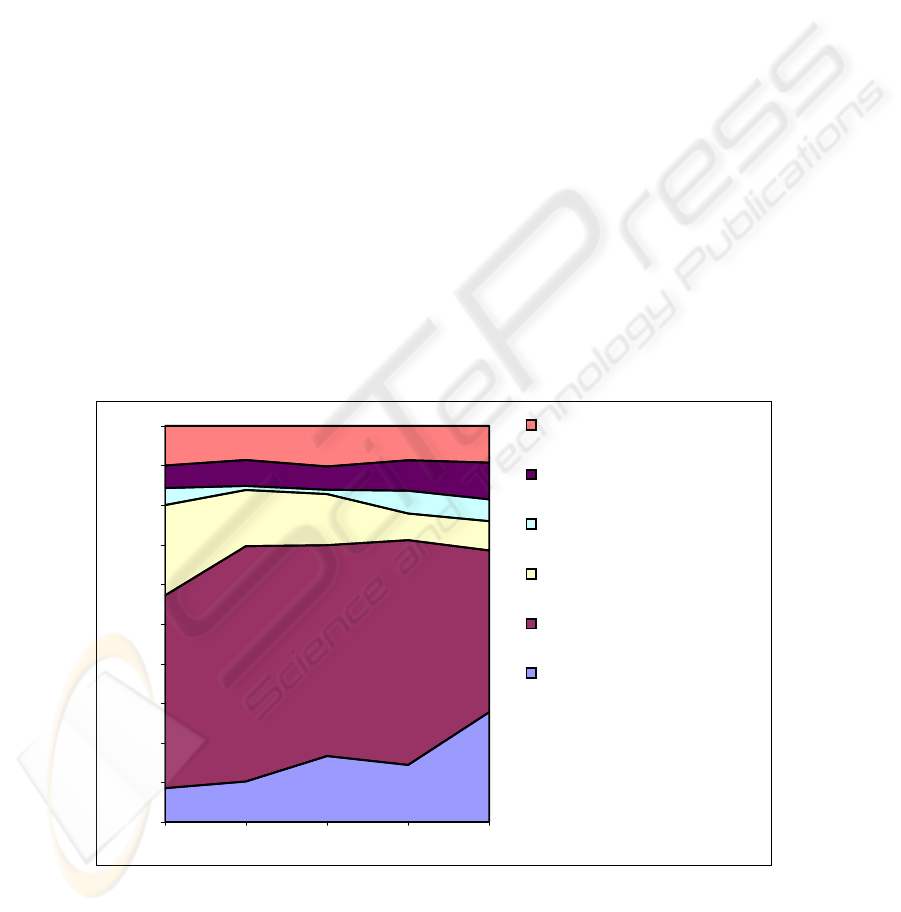

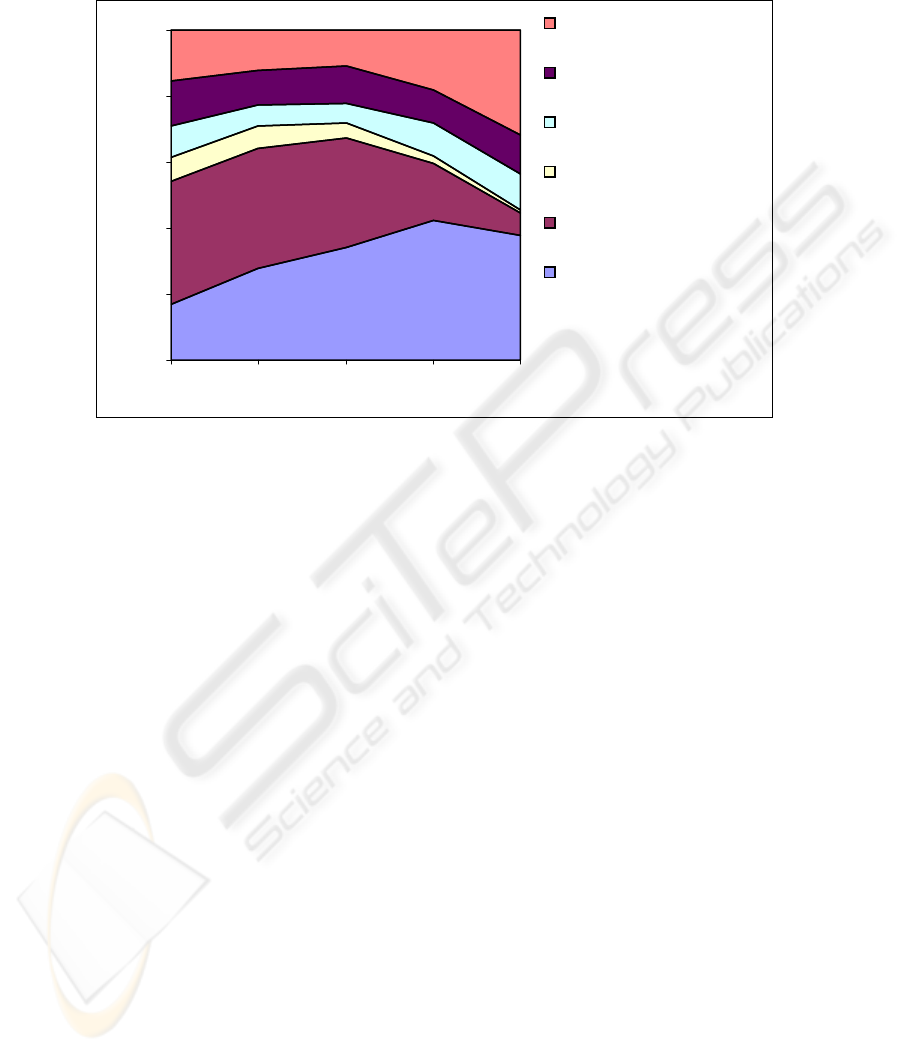

intuitive description of this phenomenon.

If for both men and women the likelihood of living alone increases with age, the

growth is more marked among women. In fact, all along the age line males show as

the most frequent living arrangement living with a spouse (with or without adult

children). A further cross-tabulation with marital status would show that even among

those men in other living arrangements, namely in complex households, the share of

individuals that cohabit with a spouse if far greater that among women.

Fig. 1. Living arrangements of Portuguese male elderly by age, in 1998

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

65-69 70-74 75-79 80-84 85+

living in complex household

without dep. children

living in complex household

with dep. children

living with adult children

living in couple with adult

children

living in couple

living alone

Source: ECHP, wave 5 (1998)

126

Fig. 2. Living arrangements of the Portuguese female elderly by age, in 1998

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

65-69 70-74 75-79 80-84 85+

living in complex household

w ithout dep. children

living in complex household

w ith dep. children

living with adult children

living in couple w ith adult

children

living in couple

living alone

Source: ECHP, wave 5 (1998)

One should also note from the graphs above that the likelihood of living in

complex/extended households increases with age, this for both gender groups. This

increase is however more pronounced among females, again undoubtedly an effect of

their greater exposure to widowhood.

As for marital status variations the single most evident trait to highlight is

obviously the strong correlation between widowhood and living alone. This is the

single most impacting event in old age as has been largely demonstrated [3].

Widowhood often means that the individual changes to living alone status. That is

what our data seem to suggest with more than 87% of those elderly living alone

declaring being widowed. Yet, it seems to be equally significant to highlight that

within the distribution of widowed elderly around 40% are not living alone,

cohabiting with other kin. Around 30% are actually living in some type of complex

extended household.

One of the crucial variables to analyse in this paper is the effect of the existence of

some type of health problem that may impose some limitations in the normal life of

the elder person, in that sense acting as a proxy indicator for the existence of specific

needs for care. One would expect to find a higher proportion of elderly living in some

form of extended household among those who declare some hampering condition

limiting their daily activities. Interestingly enough we do not observe such a clear

pattern in our data. In fact, and in a similar way across all types of living

arrangements, around 50% of the elderly declare having some hampering condition,

either severe or moderate.

However, this does not mean that the distributions found in our data are not

substantially significant. It is our belief that the data may be biased (to what extent we

could not say) by the way the variable is measured. The assessment of the existence

127

of an hampering condition is made on the basis of the self-perception the elder person

has on his/her condition. It is documented how one’s self-perception of health status

is a culturally determined construct [1]. It would be a legitimate hypothesis to rise that

elderly living alone tend to perceive themselves as more frail and in a worse health

condition than those that benefit from some type of family network. In that sense we

could expect to inflate our results in both directions according to the elderly sub-

group we are focusing.

Our interpretation of the trend of no association between the existence of an

hampering condition and the type of living arrangement of the elder person displayed

in our data is that it could also be reflecting the increasing difficulties of families to

cope with the demands falling on them and in that sense leaving severely exposed to

the risk of social exclusion a significant portion of our elderly population. In any case

it is worth highlighting that the majority of people who actually declare some

hampering condition are living with a spouse. This substantiates what other

researchers have been claiming about the couple as the main unit of care provision in

old age.

This idea results reinforced by the analysis of the engagement in caring after other

people among our sample of elderly. From table 2 we would highlight two main

aspects. On one hand it seems quite clear that the extended household tends to work

as the locus for the exchange of care. This means that if it is true that by living with

his kin, the elder person is benefiting, at least in theory, form a support network that

will help dealing with old age related problems, it is also true that in these households

the elderly tends to have himself a role as carer, namely of children. The second

aspect to highlight is precisely the reinforcement of the couple as a care unit.

Table 3 below summarises the relative impact of this set of factors when trying to

understand what are the structuring elements of living arrangements among the

Portuguese elderly. We have estimated 2 relatively simple logistic regression models

for the likelihood of finding a Portuguese elder person living in a specific type of

household. Model 1 estimates the likelihood of living alone, model 2 the likelihood of

living in some type of extended household (with or without children). We have

elected these two types of households as they can be considered the antipodes of a

familialist society.

The first summary measure to highlight is the non-significance of the gender divide

in the likelihood of finding the elder person either living alone or in

complex/extended households. This does not contradict our initial comments on the

gender differences. Those differences exist in absolute numbers. What our model

reinforces is the idea that those absolute differences among men and women do not

have a gender origin and are simply the result of the differentiated incidence of other

socio-demographic phenomena in the two groups (particularly widowhood and life

expectancy).

Contrary to gender, age and marital status do show a very significant impact in

both our models, although in different ways. As for age, younger cohorts of elderly

are more likely to be living alone (corresponding to the age interval where it is more

likely for the bereavement of a spouse to take place). Older cohorts of elderly show

more likely to be living in some type of complex household (one could infer that with

age the likelihood of needing specific care increases therefore the likelihood of

getting that care from the extended family network).

128

Marital status has a strong effect, as expected. We would call the attention to the

effect of widowhood as increasing both the likelihood of living alone and of living in

complex household.

Suffering from an hampering condition does not show any significant effect on the

choice of living arrangement, which should be read along the same lines as what was

argued before about the same topic.

Finally, we observe a significant impact from the caring status variable. It is

important to remember that we are focusing here on the elder person as a carer and

not as a recipient of care. The relevant bit of information to highlight once more

seems to be the exchange of care implied in the cohabitation of the elder person with

the extended family (the granny phenomenon).

Table 3. Summary models to estimate the likelihood of finding an elder person living alone

and living in a complex household in Portugal, in 1998

Living alone Living in complex household Factors associated to

living arrangements in

old age

Coefficient estimates

(t-statistic)

Odds

ratio

Coefficient estimates

(t-statistic)

Odds

ratio

Age group in 1994

65 – 69 (base)

70 – 74 0.761** (2.44) 2.141 -0.116 (0.51) 0.891

75 – 79 0.899*** (2.84) 2.457 -0.117 (0.50) 0.889

80 – 84 0.394 (1.20) 1.483 -0.089 (0.34) 0.915

85 + 0.157 (0.46) 1.170 0.478* (1.76) 1.613

Gender

Male (base)

Female -0.243 (1.36) 0.785 0.162 (1.14) 1.175

Marital status

Married (base)

Widowed 5.857*** (11.33) 349.595 0.973*** (6.53) 2.646

Never married 5.066*** (9.26) 158.488 1.970*** (8.87) 7.167

Separated/divorced 5.407*** (8.28) 222.930 1.610*** (3.76) 5.003

Hampering condition

No (base)

Yes 0.070 (0.48) 0.932 0.068 (0.55) 1.073

Caring status

Not caring (base)

Caring after children -1.645*** (3.23) 0.193 1.256*** (3.88) 3.512

Caring after adult -3.544*** (3.46) 0.029 0.298 (1.04) 1.347

Constant -5.994 - -2.136 -

Source: ECHP, wave 5 (1998)

Notes: * significant at 0.1; ** significant at 0.05; *** significant at 0.01

129

How much are Portuguese families looking after the elderly?

So far we have looked at where do elderly people choose to live (be that a free choice

or a constrained choice). Now we suggest looking at familialism from the perspective

of those that engage in caring after an elder person. In familialist systems the

household appears as the main locus for the provision of social welfare. The question

to ask follows logically and addresses to what extent do Portuguese families and

households reflect that trait of familialism when we focus on taking care of the

elderly.

Table 4 summarises data for the amount and the nature of engagement in care after

an elder person in 11 ECHP countries in 1998.

One could be initially surprised by the absence of any significant overall incidence

of engagement in caring after an elder person among the South European countries

(traditionally labelled as the familialist countries). That should not be the case in the

sense that it is well documented that the rates obtained for this type of broad question

are heavily influenced by concepts of care that vary enormously across countries[4].

The reality of the Northern European countries in particular is significant to illustrate

this phenomenon. Caring and the figure of the carer are well established in the public

arena of these countries, making it more straightforward for their citizens to identify

themselves as carers, even if the amount of care delivered is very reduced and most of

the time only in the form of visits to give some emotional support to an elder person

living alone. In familialist systems, on the contrary, care is usually identified with

Table 4. Descriptive variables on the amount and nature of the engagement in care after elder

people in 11 ECHP countries, in 1998 (percentages within each country)

Intensity of care giving

(% of those engaged in

care)

Location of care (%

of those engaged in

care)

Effects on paid

work (% of those

engaged in care)

Country %

caring

after

an

elderly

Less

than

14

hours

per

week

14

up to

28

hours

per

week

More

than

28

hours

per

week

Cared

after

person

lives in

household

Cared

after

person

lives

elsewhere

Caring

prevents

from

taking

paid

work

Caring

does

not

prevent

from

taking

paid

work

%

females

among

those

engaged

in care

after an

elderly

Germany 3.0 n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a.

Denmark 6.9 66.9 19.7 13.4 30.0 69.3 15.5 84.5 63.2

Netherlands 7.5 45.9 44.9 9.2 29.9 70.1 15.3 84.7 58.4

Belgium 6.8 68.7 15.6 15.7 30.2 68.7 13.5 86.5 57.1

France 4.1 64.3 22.2 13.5 35.6 63.3 6.8 93.2 63.8

UK 15.4 n.a. n.a. n.a. 31.4 64.4 n.a. n.a. 58.0

Ireland 5.1 31.2 17.5 51.3 56.9 42.6 33.3 66.7 67.6

Italy 6.6 41.6 30.7 27.7 45.7 49.8 15.9 84.1 64.3

Greece 4.1 34.0 46.1 19.8 65.2 32.2 14.8 85.2 78.4

Spain 5.8 17.3 25.9 56.8 66.6 32.3 20.3 79.7 72.8

Portugal 5.1 23.8 23.0 53.2 83.0 15.7 32.7 67.3 85.1

ECHP 6.2 53.5 22.5 24.0 49.2 48.6 18.1 81.9 64.8

Source: ECHP, wave 5 (1998)

Obs. Cases are weighted

Note: n.a. means data were not available for the particular country on the variable

130

more demanding tasks of support in daily activities.

To support our argument we should analyse in detail the data on the nature of the

provision of care in the subsequent columns of table 4. There we will find significant

variations across countries and patterns of care provision that clearly reinforces the

familialist character of the Portuguese society.

Our general remark on this would be that in Portugal caring after an elder person is

definitely a household matter, meaning that engaging in care after an elder person

usually involves cohabitation between the carer and the recipient of care. This is

associated to a proportionately higher intensity of care giving, which in turn seems to

have a stronger impact on the carer’s ability to participate in the labour market.

Although put forward in a very simple way, this is a pattern of care giving that has

lots of implications both for the elder person receiving care and for the household

providing care. The immediate consequence to raise is of a financial nature and has to

do with the income losses caused by the inability of at least one household member to

participate in the labour market as a consequence of his or her engagement in care

giving. Other consequences will cover aspects related to the burden on the carer and

on the entire household and on the emotional consequences the care giving context

often has. There is no research of a kind in Portugal on this topic, but research carried

out in other countries has shown how important it is to include in policy design not

only the needs of the elderly but also the needs of their carers [6]. In that sense any

mechanisms that can somehow alleviate the burdens on the informal family carers

making it more flexible to juggle care with other social roles, namely paid work and

leisure activities are expected to have positive effects in the overall quality of life of

the household engaged in care giving and, if not directly at least indirectly, in the

quality of life of the elder person receiving care.

The last column in table 4 adds up on this by showing how comparatively strong is

the gender bias in the Portuguese pattern of engagement in caring after an elder

person. This, if not surprising within a familialist context, does raise some worries

about the availability of informal carers in the near future. The behaviour of younger

cohorts of females as far as their participation in the labour market is concerned has

been changing significantly, with increasing levels of participation but also, as

surveys on values have been demonstrating, with a increasingly stronger orientation

towards values of self-fulfilment and individual economic independence. The joint

effect of the impact caring has on being able to keep paid work and the decreasing

availability of females to sacrifice their professional lives, may pose serious problems

of availability of carers in the near future.

Financial conditions in old age

The analysis of the financial conditions of the Portuguese elderly sub sample has

made use of rather aggregated information. We work with household income as a

more reliable alternative to personal income. By considering household income we

account for the transfers within the household and therefore get a more accurate

picture of the effective resources available for the elder person. Since the overall goal

of our analysis is to assess, even if in a crude way, the living conditions of the elderly,

the equivalent adult household income appears as the most reliable measurement. In

terms of calculations this means that the summary variable for the household income

131

is transformed according to the number of equivalent adults in the household. To

equalise the income variable we have used the modified OECD scale

1

.

The income distribution problems that characterise the Portuguese population in a

comparative perspective, namely within the EU, are well know and are well

documented. We will not focus on that. The same can be said for the problems of

income distribution within the Portuguese society. Evidence has been put forward on

the inequality problem associated to the income distribution across the Portuguese

society. A good reference for that is the work of Rodrigues, where among other

conclusions, it is demonstrated the comparative weak situation of the elderly [8].

1

The OECD equivalent modified scale for computing the household income per equivalent

adult gives a weight of 1.0 to the first adult in the household, 0.5 to the other adults and 0.3

to each child. By dividing the total household income by the OECD equivalent modified

scale we take into account in the analysis the differences in dimension and composition of

households.

Table 5. Measures of inequality within the income distribution of the elderly Portuguese

sub sample, in 1998

Measures of Inequality

1

Deciles Ratio (P90 / P10) 4.50

Share Ratio (S80 / S20) 5.74

Gini Index 0.37

Source: ECHP, wave 5 (1998); own calculations

1

The measures used are:

Deciles ratio: the ratio between the 90

th

percentile and the 10

th

percentile of the

distribution.

Share ratio: the ratio between the total amount of income of the 20% of the population with

higher incomes and the total amount of income of the 20% of the population with lower

incomes.

Gini index: it is a widely used measure of inequality particularly sensitive to transfers in the

middle of the distribution.

Table 6. Proportion of total equivalent adult income in each decil of the distribution

Decil Proportion of total income Lorenz Curve Coordinates

1

st

0.0328 0.0323

2

nd

0.0464 0.0792

3

rd

0.0537 0.1329

4

th

0.0612 0.1941

5

th

0.0679 0.2620

6

th

0.0770 0.3390

7

th

0.0913 0.4303

8

th

0.1132 0.5435

9

th

0.1534 0.6969

10

th

0.3032 1.0000

Source: ECHP, wave 5 (1998); own calculations

132

In this paper we focus on the distributional aspects within the elderly population.

The reason for this approach is the belief that one of the main challenges when

designing policies for any group is to offer solutions that maximise the equal access

of all to whatever goods are being offered. In the field of care provision this argument

seems more relevant than any other.

Tables 5 and 6 provide for some summary data about the income distribution

inequalities within the elderly sub sample.

The information contained in both tables is self-evident and gives us a clear picture

of the deep inequalities within the elderly population. The Gini index (0.37) and the

Lorenz Curve coordinates are particularly clarifying in that respect and show how

unequal is the income distribution among the elderly, with more than 45% of the total

income concentrated in the 20% better off elderly. This becomes more significant if

we remember that the income variable we are analysing refers to total income after

social transfers. We are talking about the final disposable income of the elderly.

What this picture reinforces is the idea that when targeting elderly people we need

to take into account profoundly distinct segments of elderly. More than that, we need

to keep in mind that any solution that involves a substantial provision of care

solutions by the market will raise serious equity problems in such an unbalanced

income distribution.

Our interest though, and because we are tackling the problem of care provision

from the perspective of a familialist framework, involves some more detailed analysis

that focus on the variations of income across different living arrangements. It is

argued that the choices of the elderly in terms of living arrangements are often

responding to financial constraints, in that sense working many times as strategies to

alleviate poverty. Table 7 below displays summary income data for different types of

living arrangements.

The comparison of both the mean and the median incomes of different types of

living arrangements give us a first idea of how important the family network can be in

the life of the elder person as a mechanism to alleviate poor financial conditions.

Table 7. Mean and median equivalent adult income by type of living arrangement among

the Portuguese elderly, in 1998 (in thousand escudos)

Type of living arrangement Mean income Median income Valid n

Living alone 693.4 504.0 408

Living in couple 858.8 584.2 674

Living in couple with adult children 1009.4 819.0 141

Living with adult children 1034.6 783.6 88

Living in complex households with dep.

children

1026.6 854.8 157

Living in complex households without dep.

children

1012.4 811.2 215

Total elderly sample 875.8 629.2 1716

Source: ECHP, wave 5 (1998); own calculations

133

We would highlight in particular the better off situation of the elderly living in

complex households with dependent children.

If we add to the table above information about the relative position of the elderly in

terms of the national poverty line, the effect of different living arrangements as

poverty alleviators results even more clear.

Having defined the national poverty line as 60% of the national median income,

table 8 above shows how strong the effect of the family resources is for the elderly in

alleviating poverty. One should note in particular the extremely high proportion of

elderly below the poverty live among those living alone and, although less, among

those living in couple. In any case, for both living arrangements we have elderly

people on their own. These are the groups that contribute more to the total amount of

poor. By contrast, those living in extended households seem to benefit from transfers

of family resources that significantly reduce their exposure to poverty.

These are all extremely important elements to take into account when discussing

the potential of any mechanism of care provision. Not only we have to take into

account the average disposable income of families and of the elderly in particular

(signalling clearly the unfeasibility of pure market solutions) but also the differences

among groups of elderly and the risks of introducing further inequalities in the system

if the solutions developed target the small segment of those that are better off.

5 Closing remarks

We have seen that the living arrangements of the Portuguese elderly, and despite

some signs that the traditional models are under increasing pressure, are still of a

markedly familialist nature. This in itself is of major interest when discussing care

solutions based on the elderly staying at home. The majority of the elderly in Portugal

are not living alone, although that is a living arrangement in clear expansion

(therefore to be taken into account in terms of policy design).

The consideration of the people with whom the elderly are living is in that sense a

very important issue when debating the characteristics of the technologies to

Table 8. Proportion of individuals below the national poverty line by type of living

arrangement, in 1998

Type of living arrangement Proportion of poor by

living arrangement

Proportion of the total

population of poor

Living alone 52.7 12.8

Living in couple 36.5 14.6

Living in couple with adult children 22.7 1.9

Living with adult children 26.1 1.4

Living in complex households with dep.

children

13.4 1.2

Living in complex households without dep.

children

20.0 2.6

Total elderly sample 34.7 -

Source: ECHP, wave 5 (1998); own calculations

134

implement and the extent to which they require interaction with the human element.

This human element is very likely to be there in the Portuguese case so it should be

triggered as a resource available. This seems to be equally important from the

perspective of the existing carers, making it worth to discuss the potentially

complementary character of these new technologies to the care provided by the

families.

However, any serious discussion on the advantages of implementing a particular

solution to care after the elderly has to go hand in hand with considerations about the

financial viability of that solution. In this paper we have limited our contribution to

putting forward the existing financial conditions of the Portuguese elderly,

highlighting their limited resources to deal with any market-based solution. The

overall income asymmetries of the national population are clearly reproduced (if not

reinforced) among the elderly sub sample. Debates on policy design must always be

based on equity principles. It is our belief, given the data available, that there is a

clear danger of reinforcing existing inequalities if we are to base the provision of

these new mechanisms of care on market forces.

References

1. Fry, C.L.: Culture, Age and the Infrastructure of Eldercare in Comparative Perspective.

Journal of Family Issues 21, 6 (2000) 751-776

2. Guerrero, T.J., Naldini, M.: Is the South so Different? Italian and Spanish families in

comparative perspective. In: Rhodes, M. (ed.): Southern European Welfare States. Between

Crisis and Reform, Frank Cass, London (1997) 42-66

3. Iacovou, M.: Health, Wealth and Progenity. Explaining the Living Arrangements of Older

European Women. Institute for Social and Economic Research, Colchester (2000)

4. Kendig, H., Hashimoto, A., et al. (eds.): Family Support for the Elderly. The International

Experience. Oxford University Press, Oxford, New York, Tokyo (1992)

5. OECD: Caring for the Frail Elderly People. Policies in Evolution. OECD, Paris (1996)

6. Pickard, L.: Carer Break or Craer-blind? Policies for Informal Care in the UK. Ageing and

Society 20, 6 (2001) 441-458

7. Pickard, L., Wittenberg, R., et al.: Relying on Informal Care in the New Century? Informal

Care for the Elderly People in England to 2031. Ageing and Society 20, 6 (2000) 745-772

8. Rodrigues, C.F.: Income Distribution and Poverty in Portugal (1994/95). INE (available

online at www.ine.pt

)

135