Health and society – conceptual paradoxes and

challenges for a business plan, for a new political agenda

and for a strategy for action in the information age

Angela Lacerda Nobre

Escola Superior de Ciências Empresariais do Instituto Politécnico de Setúbal ESCE-IPS

Campus do IPS, Estefanilha, 2914-503 Setúbal, Portugal

Abstract. The present paper considers the activity of tele-care within the broad

framework of the information age, of how modern society is organised and of

the structuring role of the health sector. The importance of key concepts such as

social structures, human agency and the instance of being-in-the-world, are

highlighted and explored. The inputs of computer ethics, critical realism and

philosophy of action are used and presented. These conceptual arguments are

applied to the particular settings of tele-care business planning and of policy

making. This paper assumes the controversial role of questioning our own

assumptions as thoroughly as possible, and of working from that questioning

process.

1 Introduction

The current paper has the main objective of exploring the links and relations between

theoretical, conceptual and philosophical inputs, and their outputs, applications, and

products at social and cultural level. In other words, this paper argues that current

practices and structures are fundamentally determined by a historical and situated

development of mentalities and conceptions. The better we are able to acknowledge

and to understand these links, the better able we become to have an effective role in

the current settings and within the present social structures of the information age.

Health service provision, in particular tele-care, may be substantially improved, and

developed conceptually and in practice, if we undertake the necessary mediations and

theory building steps.

Thus, section number two relates tele-care with the technological revolution and

stresses the underlying dynamism which it hides. Section three, refers to the areas of

health and education and their role in society. Section four, takes this structuring role

and relates it to the importance of social structures and of human agency. Section five,

refers to social complexity and to the historical philosophical development, stressing

the role of technological revolutions. Section six, focus on the computer revolution

and on the revolution of mentalities. Section seven, refers to ‘the world and our role in

it’ from the perspective of institutional and organisational settings. Section eight,

deals with the implications to a business plan of a tele-care activity of the present

Lacerda Nobre A. (2004).

Health and society – conceptual paradoxes and challenges for a business plan, for a new political agenda and for a strategy for action in the information

age.

In Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Tele-Care and Collaborative Virtual Communities in Elderly Care, pages 143-159

DOI: 10.5220/0002682601430159

Copyright

c

SciTePress

arguments and also to their importance to the policy making areas. Finally, the present

paper offers three figures which schematise the arguments developed within its main

text.

2 Tele-care and the technological revolution – the underlying

dynamism

The idea, the possibility and the concept of tele-care can only exist because there has

been a technological development, namely the development of computer technology

and of the information and communication technology, which enabled this possibility

to occur. When considering tele-care activities we are performing a double analysis:

(i) on the potential and possibilities being opened by the new technology, and (ii) on

our current understanding of what health care means, incorporates and signifies.

However, both these questioning processes are inherently dependent on broader and

more general conceptual frameworks. These frameworks can be understood as a

general mentality or as the current cultural perspective of a specific time and place:

for instance, the early twenty first century Western world view on whatever we may

be considering. These broad lines of thought have a deep and profound impact in the

way we interpret our daily lives and directly affect our decision making processes. As

researchers we obviously cannot simply step out of our ingrained culture though, as

social scientists, we have the privilege as well as the burden of potentially being more

aware of the forces and influences which determine us as well as which directly affect

our actions.

Within the general range of human activities, the ones related to the broad areas of

health care and education present a degree of sophistication and of complexity that is

seldom recognised. In order to grasp this complexity, as well as in order to profit from

the potential that they have to offer, it is necessary to revise our deepest assumptions

and reasoning processes. Our culturally and socially determined perspectives include

both dead ends and conceptual knots, as well as potentially creative ideas and

innovative concepts. The task of the present paper is to consider the specific context

of tele-care activities, and to revise and, when possible, to reformulate common

conceptions in order to help to bring in new, innovative and breakthrough conceptual

perspectives able to inform and change current practices.

3 Health and health care, and education and learning, in the

information age

As society developed, one critical dimension has been the transference from the

private to the public domain of the activities related to health and education. Mass

care and education are a benefit of modern societies. On the other hand, this

transference has implied a certain dismissal from individuals and families in relation

to issues which were initially under their direct and personal sphere. According to the

perspective taken in this paper, this apparently minor issue constitutes one of the

deepest and most serious concern to be considered by modern societies. It is the main

144

objective of this paper to explain why. A second objective is the statement that a tele-

care initiative may consist on a pilot experience where an alternative conception of

health and education may be tested and experienced. A third potential aim is to use

both a new conceptual framework as well as the possibility of a concrete experience

to inform and transform current policy making.

With a limited paper length, it is not possible to develop extensively such

ambitious objectives so that the first and main aim, that of clarifying and stressing the

importance of common conceptions and general theoretical frameworks in

determining our actions and our perceptions of ourselves, of the world, and of our

place in the world, will take the lion’s share of the current paper. The importance that

health and education have in society is related to their potential to influence and

determine a society’s overall mentality. Of course that socialisation and culturisation

processes cannot be subscribed to specific and direct activities as they are embedded

at every level of social interaction through all stages of life. Nevertheless, it is critical

to recognise the potential that health and education have to impact on individual’s

conceptions and this happens as much in singular terms as well as at group and

community level. It is the strength of these ties and links which keeps a society

together. And it is these dynamisms which constitute a society as such.

Within the educational field, we are witnessing a change in practices and

perspectives. The traditional reliance on expository methods and on heavy time

schedules is giving rise, at school level, to time for both team work as well as

independent study. At university level the pressure is even greater to transfer more

time and responsibility to the student, through access to better resources, greater

freedom to pursue different methods, and more peer interaction even at international

level. The harmonisation being defined at European level, bringing together the

different educational policies of European Union member countries, includes and

stresses these changes. The student-teacher relationship as well as the patient-doctor

relationship are changing accordingly. From a traditional and conventional position

where both teacher and doctors were generally considered as the only legitimate and

credible sources and possessors of all relevant knowledge, who would expose and

deliver their insights to receptive and passive listeners, now we have a model where

both sides are more in balance, where both parts share different types of contents and

of skills and the idea is that they work together to achieve common goals. Active

students and patients help to bring better quality results.

This model and perspective is part of an overall movement which the present paper

aims at deciphering and clarifying. The basic argument is the following: the

knowledge economy of the information age represents a major change in relation to

previous reality. Though most changes still remain encapsulated at a potential level,

many have already been realised. The overall change process, due to its immense

complexity, cannot be fully predicted or planned as was often possible in previous

and more stable environments. Thus a sensible solution is to aim at improving the

flexibility and adaptability of every activity. For instance, within education, instead of

relying only on fixed and rigid acquisition of lists of contents, the shift has to be

towards focusing on the learning process itself and on improving its potential through

a learning-to-learn and learning-by-doing approach. Similarly, under this new

perspective, each doctor recognises the role of the patient as a key and unavoidable

partner, one who has the ultimate say in most health related matters.

145

In parallel with this positive shift we witness an inversion in terms of areas which

were not typical health problems and which now represent major health issues.

Pregnancy, though not an illness, represents an important health care area. In terms of

public health, the hospital provision of obstetric services is an important achievement.

However, when there is an unusual and unfounded rise in caesarean interventions we

may question what kind of role health care is representing in these cases. More

importantly, this question is raised when there are situations which belong to the

realm of daily life such as health related problems connected to professional stress.

Besides the huge importance of health-professional stress issues there are many others

to take into account. When faced with life changing situations such as the death of a

member of the family, unemployment or divorce, it is common to see a call for help

through health service providers.

The question that we raise is not a yes or no, black or white, right or wrong

discussion on the acceptability of these situations. The issue that we want to call

attention to is that health and educational instances have a critical role to play in

society and this role cannot be performed by a simple transference of responsibilities

from one sphere to the other, i.e. from the private, personal and family sphere to the

public, official and institutional sphere of service provision. There are many levels of

complexity and it is necessary to grasp them as thoroughly as possible. One central

problem is the reliance on a health system which is based not in preserving health but

is solving illnesses. Preserving health is not simply vaccinating or promoting

prevention campaigns. Health maintenance is much more than this and cannot be

exhaustively defined. Fundamentally, it has to do with the deep and ingrained values

that a society transmits and represents.

One possible answer to this puzzle is the avoidance of the exclusive reliance on a

medically based and illness centred approach, such as we currently have in most

Western world health systems, and to focus in two pairs of main ideas. The first pair

is related to (i) health and to (ii) health care, and the second pair is related to (iii)

education and (iv) learning. The points to acknowledge are the following: (i) first, that

health related issues are to be dealt with within a therapeutic relationship. This

relationship includes, but is not reduced and limited to, the circle of professional

health providers, rather it is extended and includes all relevant social relations. (ii)

Second, that a therapeutic relationship is one that helps each individual to deal in the

best possible way and according to each one’s potential with the specific situation and

reality that is being faced, i.e., to care is to help others learn to care for themselves.

TO LEARN = to participate in this collective experience which

is a transformation and a recreation developmental process.

A patient with a terminal disease or one with a minor injury may both benefit from

a relationship that helps them to deal with their unique reality by making the most of

their own resources, no matter how limited or how rich they are. To put in another

words, it is through a creative and constructive relationship that human beings may

develop their full potential. These relationships are socially and culturally embedded.

Accordingly, it pays off to invest as much as possible in devising ways that help us to

improve social interaction and to transform this interaction in generative and

distributed ways of potential building and reification, i.e. to invest in effective

therapeutic relationships. It is by achieving more, in terms of therapeutic

146

relationships, that more may be achieved, in terms of potential development. It is by

stretching and fulfilling current potential that future potential may be increased. It is

by exploring all possible current developmental opportunities that future development

may be achieved. It is by opening up to present reality that future opportunities may

be created. The second pair of issues centres on education and learning to stress that,

(iii) first, the previously mentioned social interaction and developmental process,

which is integral to the therapeutic relationship, is inherently, intrinsically and

constitutivelly a learning process. (iv) Second, that education, if it is to fulfil its

potential and its true domain it has to acknowledge the learning dimension of all

social interaction, and thus it has to promote social structures and practices which take

this strength into account. Possibly, what we are referring to, is a revolution in

mentalities. A revolution in mentalities may be achieved by a revolution in the way

health and education are seen, delivered and used. A revolution in health and

education is even more drastically revolutionary if we take into account the changes

implicit in the computer revolution of the information age. A tele-care project, a

simple and non ambitious health care provision project, inherently transports all this

complexity and also all this potential.

4 Health and education as structuring sectors of a society – world

views, social conceptions and human agency

Health care and education represent two of the most critical areas within a society.

Together with other broad impact areas they are structuring sectors of an economy,

defining, conditioning and determining the bedrock from where other economic

activities develop. The physical infrastructures, the public transport facilities, the

communication network, the law and justice system, the media, and the political

system are all examples of baseline structuring sectors. However, the specificity of

health and education far exceed the impact of others. It is not a question of

quantitative, direct, immediate or short term impact, the sort of influence which may

be reasonably measured, predicted and planned. The crux of the issue is that both

health and education, taken in their broadest sense, represent the first and determining

conditions for further development. All others, though they may share some degree of

impact at this level, generally interfere at a later level, more related to solving

problems and designing solutions. The creative, generative, innovative, long term

capacity to develop is strongly determined by the health and education areas of a

society. This could be taken as wishful thinking though the validity of this assertion

most probably depends on how we may define and interpret what we include in the

societal field of health and education.

Two issues may be of relevance here. The first one is what concept of the human

being we are using. And the second one is how we relate this concept with how the

world works or, better, with whatever perception we have of how the world works.

Both the arguments of the previous sections as well as of the next sections are

summarised in the graphical schemes presented in Figure One – ‘World view and

action’, Figure Two – ‘Social structures and social practices’, and Figure Three –

‘Human agency as the product of a social relationship and of a learning process – the

potential role of health care and education’.

147

In terms of general mentality and ingrained culture we, the Western society of the

early twenty first century, are still deeply influenced by the concept of human beings

as rational, autonomous and independent entities which was the product of the

philosophical theories of the Enlightenment period of the seventeen and eighteen

centuries. The rationalist theories such as those of I. Kant, as well as the utilitarian

conceptions, such as those from J. Bentham and J. S. Mill, are representative of such

conceptual approaches and philosophical theories. In face of this it is hardly

surprising that most management theories and models, and even business or computer

ethics, are conceptually based on these broad theories.

A critical concept to this analysis is the idea of human agency, understood as the

individual capacity to interfere with, and to change and influence the areas and

spheres to which each individual has access to. It is this capacity that may determine,

in cumulative terms, and in the long run, how societies change and develop. In order

to understand and to explore these influences we will use three broad level references.

Firstly we will use K. Gorniak-Kocikowska comments on the historical development

of Western philosophical thinking, applied particularly to the computer ethics field of

study [8]. Secondly, we will use Roy Bhaskar’s critical comments on the importance

of social structures and human agency [1]. And thirdly, we will refer to the works of

J. Gonçalves [7] within the field of action philosophy in order to bring in critical and

fundamental concepts.

5 Social complexity and historical philosophical development – the

role of technology revolutions

In order to understand current mentalities and commonly shared understandings it is

fundamental to step back and to distance ourselves from current thinking patterns

through the use of historical social and philosophical analysis. This is what Gorniak

proposes and she traces current thinking to centuries’ old influences.

Gorniak, referring to the field of computer ethics, states that «Since... prominent

scholars... use the ethics of Bentham and Kant as the point of reference for their

investigations, it is important to make clear that both these ethical systems arrived at

the end of a certain phase of profound and diverse changes initiated by the invention

of movable printing press.» [8](italics in the original text). The first printed book in

Europe was J. Gutenberg’s ‘Constance Mass Book’, in 1450, and forty years later

there was already the profession of book publishers [8][9]. At a foot note to this

comment Gorniak adds: «Of course the printing press was not the only cause of such

profound changes, but neither was the steam engine or the spinning machine. I do

recognise the tremendous complexity of the processes we are talking about.»

[8](italics not added). In the main text, continues: «The question is: were these ethical

systems merely solving the problem of the past or were they vehicles driving

humankind into the future?» [8]. Gorniak claims that the ethical systems of Kant and

Bentham were created during the time of the Industrial Revolution, but they were not

a reaction to, nor a result of, the Industrial Revolution of the eighteen and nineteen

centuries. Gorniak explains:

«There was no immediate reaction in the form of a new ethical theory to the

invention of the printing press. Rather, problems resulting from the

148

economic, social, and political changes that were caused by the circulation of

printed texts were at first approached with the ethical apparatus elaborated

during the high Middle Ages and at the time of the Reformation. Then, there

was a period of growing awareness that a new set of ethical rules was

necessary. The entire concept of human nature and society had to be revised.

Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau, and others did that work. Finally, new ethical

systems like those of Kant and Bentam were established. These ethics were

based on the concept of the human being as an independent individual,

capable of making rational judgements and decisions, freely entering the

‘social contract’. Such a concept of the human being was able to emerge in

great part because of the wide accessibility of the printed text.» [8].

Gorniak stresses that the ethics of Kant and Benthan were both manifestations of

and summaries of the European Enlightment: «They were created at a time when

Europeans were experimenting with the idea of society’s being a result of an

agreement (a ‘social contract’) between free and rational human individuals, rather

that the submission to divine power or to the power of Nature. Moreover, such a new,

contractual society could have been created in separation from traditional social

groups. The conquest of the world by Europeans... made it possible.» [8] (italics in the

original).

According to Gorniak, despite Kant’s and Bentham’s claims of universalism, their

concepts of the human being refers to European man as defined by the Enlightenment,

as free and educated enough to make rational decisions. Gorniak specifies:

«’Rational’ means here the type of rationality that grew out of the Aristotelian and

scholastic logic and those mathematical theories of the time of printing press

revolution. This tradition was strengthened by ideas of Pascal, Leibniz, and others;

and it permitted one to dismiss from the ranks of partners in discourse all individuals

who did not follow the iron rules of that kind of rationality. The term ‘mankind’ did

not really apply to such individuals. Finally, this tradition turned into Bentham’s

computational ethics and Kant’s imperialism of duty as seen by calculating reason.»

[8]. Gorniak concludes that the nature of both ethical systems must be «very attractive

and tempting for computer wizards, especially for those who grew up within the

influence of the ‘Western’ set of values.» [8].

This argument develops in the context of the discussion of the impacts of the

current computer revolution and Gorniak stresses and resumes the main ideas stating

that: «It now seems very likely that a similar process of ethical theory development

will occur... The Computer Revolution is revolutionary; already computers have

changed the world in profound ways... My claim is that the number and difficulty of

the problems will grow. Already, there is a high tide of discussions about an ethical

crisis in the United States. It is starting to be noticeable that traditional solutions do

not work anymore... The more computers change the world as we know it, the more

irrelevant the existing ethical rules will be and the more evident will be the need for a

new ethic.» [8].

Gorniak’s impressive account highlights the crux of the problem. In order to grasp

why and how health and education are so critical to society we must first

acknowledge what kind of conceptual framework we currently have to situate and

ground our thoughts about the human being. According to Gorniak, most current

theories, at least in the field of computer ethics, are grounded in rationalist and

utilitarian ideas.

149

6 The computer revolution and the revolution of mentalities

A double issue is at stake in the argument that this paper develops: (i) that computers

are changing the face of the world and creating the knowledge economy of the

information age [10], and (ii) that there is a vast range of alternatives in terms of

philosophical theories about the concept of a human being. Each of these theories

corresponds to a general and society level mentality.

One philosophical conception is that humans are ‘deficient’ animals as they have

not been born with any particular skill or speciality. All other animal species have an

innate capacity to fly or to swim, or to perform whatever activity which guarantees its

survival in the environment where they are born. Humans, on the other hand, have a

tremendous capacity to learn and to adapt to very diverse conditions. This malleability

is exactly the characteristic that J. Moor [4][11] argued that made computer

technology genuinely revolutionary and different to all previous technologies. Moor’s

suggestions about the information age are rooted in a perceptive understanding of

how technological revolutions proceed.

«Computers are logically malleable in that they can be shaped and moulded

to do any activity that can be characterised in terms of inputs, outputs and

connecting logical operations... Because logic applies everywhere, the

potential applications of computer technology appear limitless. The computer

is the nearest thing we have to a universal tool. Indeed, the limits of

computers are largely the limits of our own creativity.» [11].

In terms of possible contributions to the concept of human beings, critical realism,

and the works of Roy Bhaskar’s, the father of this conceptual framework, are relevant

and they introduce a new tone. Archer and Bhaskar [1] state:

«... all agents have practical knowledge (not necessarily cognitively

available) and some degree of understanding of the real nature of social

structure which their activities sustain, [however] unintended consequences,

unacknowledged conditions, and tacit rules limit the individual’s

understanding of his or her social world.»

A further level of complexity may be introduced through the specific perspective

of philosophy of action, which will be further developed in the next section.

According to J. Gonçalves [7], there are two opposing interpretations of philosophy:

one more theoretical, contemplative and interior to the human process of thinking;

another one, which interprets philosophy as a doing, as a practice, and as an action.

As philosophy is highly complex both interpretations are possible. Philosophy of

action stresses the meaning creation process inherent to all human action.

There are also two distinct possible perspectives of analysis: «the subject-object

instance refers to the closed relationship, unidirectional, between the researcher, the

subject, and his object of research; the being-in-the-world instance, a concept of

contemporary philosophy, precedes and includes the former one, and is ontologically

rooted thus bringing forth the concept of the world and the unity of action.» [7](italics

in the original text). Ontology is the manifestation of being of all reality. According to

this author, the action involved in the development of human beings and the action

involved in the development of the world, is inherently the same. It is not possible for

human beings to manifest themselves unless in a constitutive relationship with the

150

world. The world is, then, «no longer the mere object of the consciousness of the

subject.» [7](italics in the original text).

Gonçalves stresses a particular point: «Philosophy must be critical but through the

demand of ontological development, through hierarchisation and selection. If we use

the notion of philosophy focused on human’s inner transformation or in a critical

attitude, then there is the risk that this approach will overlook the central role of

action in the world and its essential de-centring process.» [7]. This comment calls

attention to the dangers of pure and reductive cognitivist, mentalistic or voluntaristic

positions which are common within positivist perspectives of reality. If we conduct a

thorough analysis of current perspectives within the general field of management and

of organisational studies we will conclude that most would subscribe to this specific

position. This author stresses that pseudo-education or a reductive approach to

learning is the effort to transform human beings as if they were an isolated

psychological entity, with no constitutive relation with the world. It is thus necessary

to develop the world in order to educate and to transform human beings, as this is the

only way that humans can change. However, according to Gonçalves, instead of de-

centring, as much as possible, human beings in the world, humans are often reduced

to a diminutive and artificial psychological world, especially the one indicated by

consciousness.

7 The world and our role in it – the organisational and institutional

settings

To clarify the argument which is being developed, we stated not only that health

and education were critical structuring areas of a society but also that they were

especially so, i.e. they have a specificity and a idiosyncrasy which enables them to

have an a priori effect, creating the basic conditions from where other areas

departure. We argued that in order to grasp the dynamism of these effects it was

necessary to take into account our common and current vision and conception of the

human being and of the world, that is, the common features of our general mentality.

Under this task, we revised several authors points of view, and stressed their implicit

message: our general mentality is still being basically influenced and determined by

the Enlightenment perspectives of rationalist and utilitarist conceptions, and by the

Cartesian mentalistic idea of rationality.

Critical realism and philosophy of action present alternative perspectives to the

conception of the human being, perspectives which call attention to the (i) importance

of the social relations and of the social structures, as well as to (ii) how humans are

defined within a thorough immersion in a specific ‘world’ and reality, the being-in-

the-world philosophical instance. In order to clarify this notion of the world, the way

that we interpret the social contexts to which we belong, we can use the specific

setting of an organisation or an institution.

According to Gonçalves’ work on the philosophy of action [7] rationality is not a

structure, a paradigm, nor a frame or a rigid law, permanently defined; it is the

meaningful reality which emerges from action, which is the process of constituting an

organised whole. Rationality cannot be reduced to mental schemes, as it is nurtured

from a global rationality which arises from the structure of action. Humanism should

151

not be reduced to the world of human beings but considered as the humanism of the

world, as the value of humans within the world process. Within an institutional

context, the perspective of the philosophy of action, according to Gonçalves [7],

considers the community as a key ontological manifestation of the world which has a

decisive role in the development of the instance of being-in-the-world. A community

may be understood from different perspectives, ranging from the psychological level

to the sociological one. The deep soil of an institution, however, is its ontological

grounding, in particular and especially that of its community. When the presence of

human beings is referred, it is not the individuals themselves, nor the sum of all

individuals, that are being referred to but rather the community itself whose statute

largely overpasses the simple sociological horizon. The maximum degree of

possibilities of being-in-the-world has in a community, thus interpreted, its

fundamental interpreter and protagonist.

At organisational level, the practices and processes are supported by social

relations which may be characterised as social structures. Archer and Bhaskar [1]

develop extensively the notion of social structures, posing the question as to how they

should be conceptualised. These authors argue that individuals and persons surely

exist, though social structures do not exist in the sense of either of these. Roy

Bhaskar, the father of critical realism theory, argues that without the concept of social

structure, or something like it, we cannot make sense of persons, since «all the

predicates which apply to individuals and mark them uniquely as persons are social.

We can predicate a shape, size and colour of a person just as we can of a stone or a

tree... but the moment we say that the person is a tribesman or a revolutionary, cashed

a check, or wrote a sonnet, we are presupposing a social order, a banking system and

a literary form.» [1]. Bhaskar insists that the problem is that we need the idea of a

social structure, but that a social structure does not exist in the same way as a

magnetic field. «... society is incarnate in the practices and products of its members. It

does not exist apart from the practices of the individuals; it is not witnessable; only its

activities and products are.» [1](italics in the original). Structures are both medium

and product, enabling and constraining.

Since social structures do not exist independently of activities, they are not simply

reproduced but are, as Bhaskar notes, reproduced and transformed. This author

explains that it is because society is incarnate in the practices of its members, that it is

easy to lapse into methodological individualism, in which society disappears and only

individuals exist. Of course, «society has not disappeared, since these individuals are

persons and their acts are situated, not simply in a ‘natural’ world but in a world

constituted by past and ongoing human activity, a humanised natural and social

world.» [1](italics in the original).

The argument of these authors follows that because social structures are incarnate

in the practices of persons, this means that they do not exist independently of the

conceptions of the persons whose activities constitute (reproduce, transform) them. It

is because persons have beliefs, interests, goals, and practical knowledge acquired in

their epigenesis as members of a society that they do what they do and thus sustain

(and transform) the structures. Bhaskar further elucidates this point: «... changes in

activity do change society. This suggests that social science is potentially liberating.

For Marx, social science was revolutionary... one must conclude that the modern

social sciences have been, unwittingly or not, defenders of the status quo. As Veblen

put it, rather than ‘disturb the habitual convictions and preconceptions’ on which

152

present institutions rest, social science has ‘enlarged on the commonplace’ and

offered ‘complaisant interpretations, apologies and projected remedies’ – none of

which have been dangerous to the status quo.» [1].

Most fundamentally, this was a result of the failure on the part of mainstream

social scientists to acknowledge that, while social reality is real enough, it is not like

‘unchanging nature’, but is just that which is sustained by human activities, activities

regarding which humans have the only say. If people are causal agents, they are

capable of re-fashioning society in the direction of ‘greater humanity, freedom and

justice’ [1]. To do this, of course, they must (i) see that they have this power; they

must (ii) acknowledge that present arrangements can be improved; and they must (iii)

have some clarity about how they can be improved. But even if they have some grasp

of the reality of society, the solitary individual cannot make change. For change to

come about, practices must be altered, which means that most of those engaged in

reproducing the practices must together alter their activity: «The aim of social science

is an understanding of society and social process, where ‘understanding’ does not

have any special sense – for example, involving empathy or some intuition of

subjectivity. To be sure, action is meaningful, and understanding society involves

understanding what acts mean to actors, but while this is part of the story, it is not the

whole of it... it also involves, as Marx saw, a knowledge of how definite practices are

structured, the relations between social practices and structured practices, and the

tendencies of such practices towards transformation or disintegration.» [1].

There is some parallelism with specific approaches set forward by organisational

literature. Peter Senge [13] states that: “Organisations change only when people

change” and “People change only when they change from within”. To learn, to

acquire, to create knowledge, is a social process thus not an individual and isolated

task. Personal learning as any personal phenomena is intrinsically and inherently

social in essence. The notion of knowledge as values and beliefs is also constitutively

socially structured. “Knowledge, unlike information, is about beliefs and

commitments” [12]. And also: “The power of Knowledge to organise, select, and

judge comes from values and beliefs as much as, and probably more than, from

information and logic.” [6]. Organisations cannot be regarded as objective and neutral

entities as it is critical to recognise the powerful impact of people’s beliefs and values

- people’s thoughts and actions are inescapably linked to their value system, they are

integral to knowledge, determining what the knower sees, absorbs, and concludes

from her observations. People with different values ‘see’ different things and organise

their knowledge according to their values. Argyris and Schon [2][3] are two of the

founders of the field of organisational learning, and their concept of double-loop

learning, which implies the constant questioning of our assumptions, stresses this

precise point of permanent reflection and self-criticism, i.e. of constantly trying to

disclose the lenses which we use to see, read and interpret the world.

153

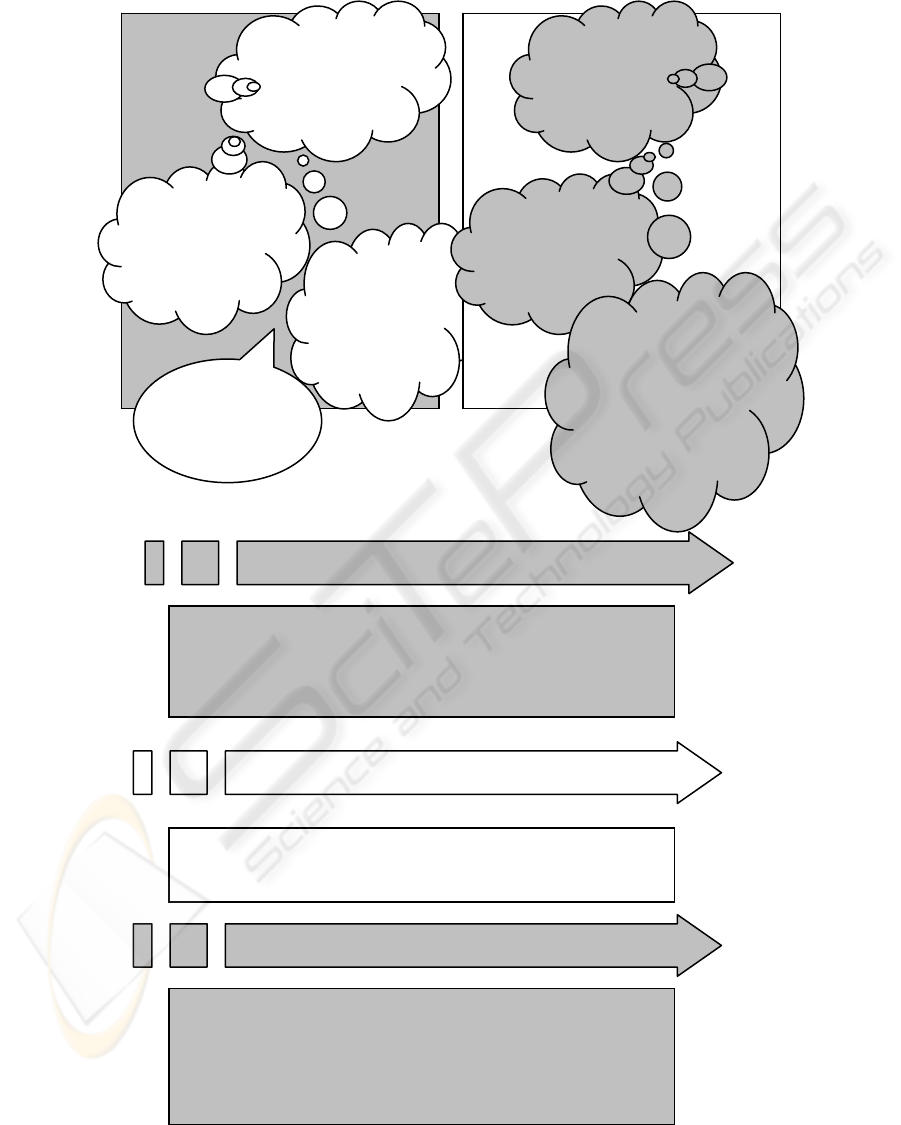

Figure One – World view and action

Our vision,

conception, idea

of the WORLD,

includes...

Our vision,

conception, idea

about ourselves,

about our own

SELF

And our ROLE

and place in

that WORLD,

i.e. how the

WORLD and

SELF relate

It also includes,

implicitly, our

conception of

the UNIVERSE

Our

CONCEPTION

of the world

determines and

conditions...

Our

PERCEPTIONS

, ACTIONS

and

DECISIONS

And it is

CONSTRUCTED

and STRUCTURED

through our SOCIAL

EXPERIENCES and

DYNAMIC

INTERACTIONS

with the WORLD

CONCEPTIONS

World Self Role of Self

Universe Human beings Role of human beings

determine and condition our

PERCEPTIONS ACTIONS DECISIONS

THIS IS A DYNAMIC and CONTINUOUS PROCESS

IT IS AN INTERACTION

and IT IS AN EXPERIENCE

This implies that perceptions, actions and decisions

ALSO determine and condition our conceptions

154

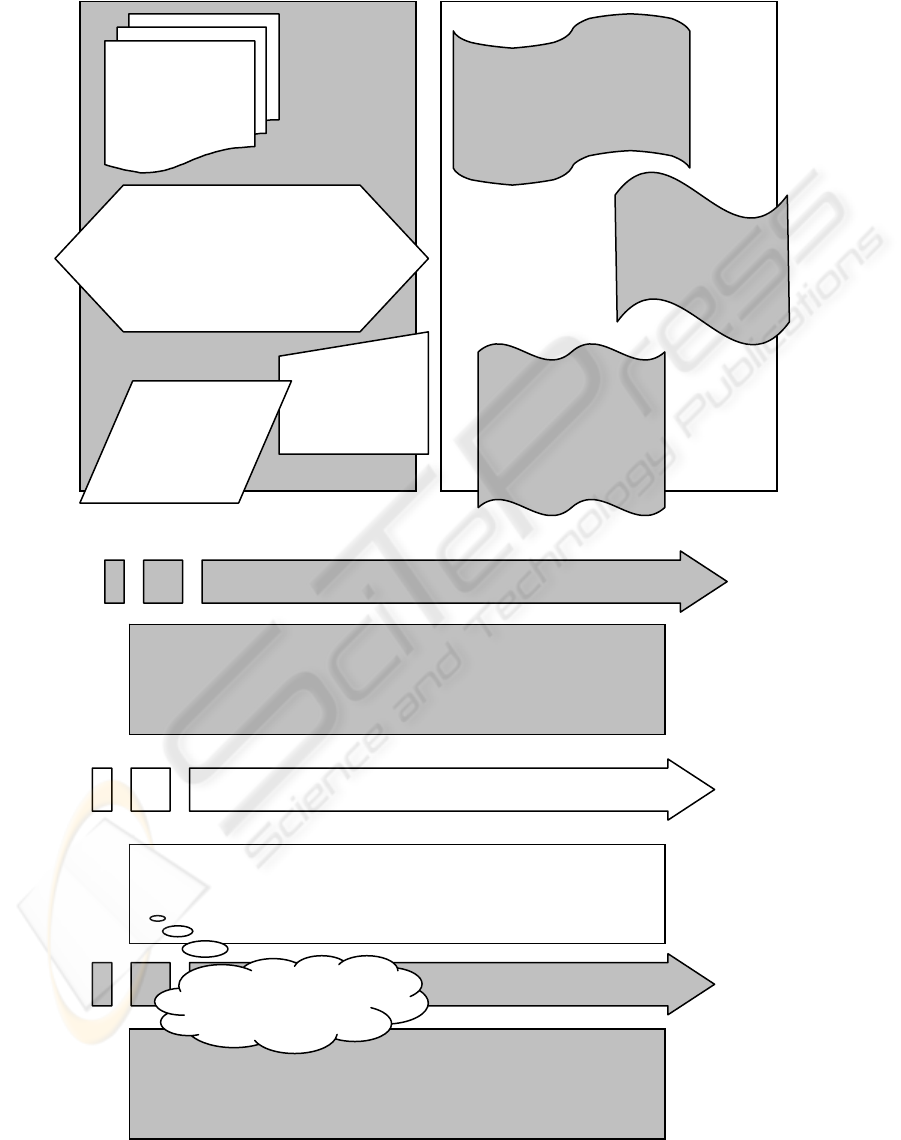

Figure Two – Social structures and social practices

A dynamic social

interaction

is an

EXPERIENCE

This experience can be best

understood through a

BEING-IN-THE-WORLD instance

instead of a SUBJECT-OBJECT

relationship

... because it is

SOCIALLY

and

CULTURALLY

embedded

... thus it is a

COMPLEX

PROCESS

An experience, a dynamic

social interaction, a being-in-

the-world phenomena, is a

CONSTRUCTED process

... it is a

constructed

STRUCTUDED

process

... through the

SOCIAL

STRUCTURES and

SOCIAL PRACTICES

in which we take part

EXPERIENCE

Dynamic social interaction Socially and Culturally embedded

Being-in-the-world phenomena Complex process

This means and this implies that this experience,

this dynamic process,

is CONSTITUTIVELY

socially CONSTRUCTED and socially STRUCTED

That it is worth to become ATTENTIVE and to ACKNOWLEDGE the

crucial importance of the way we CONSTRUCT and STRUCTURE the

communities, groups, organisations, relationships and practices that

constitute ou

r

SOCIAL realit

y

And, in turn, what

does this

mean and

im

p

lies?

155

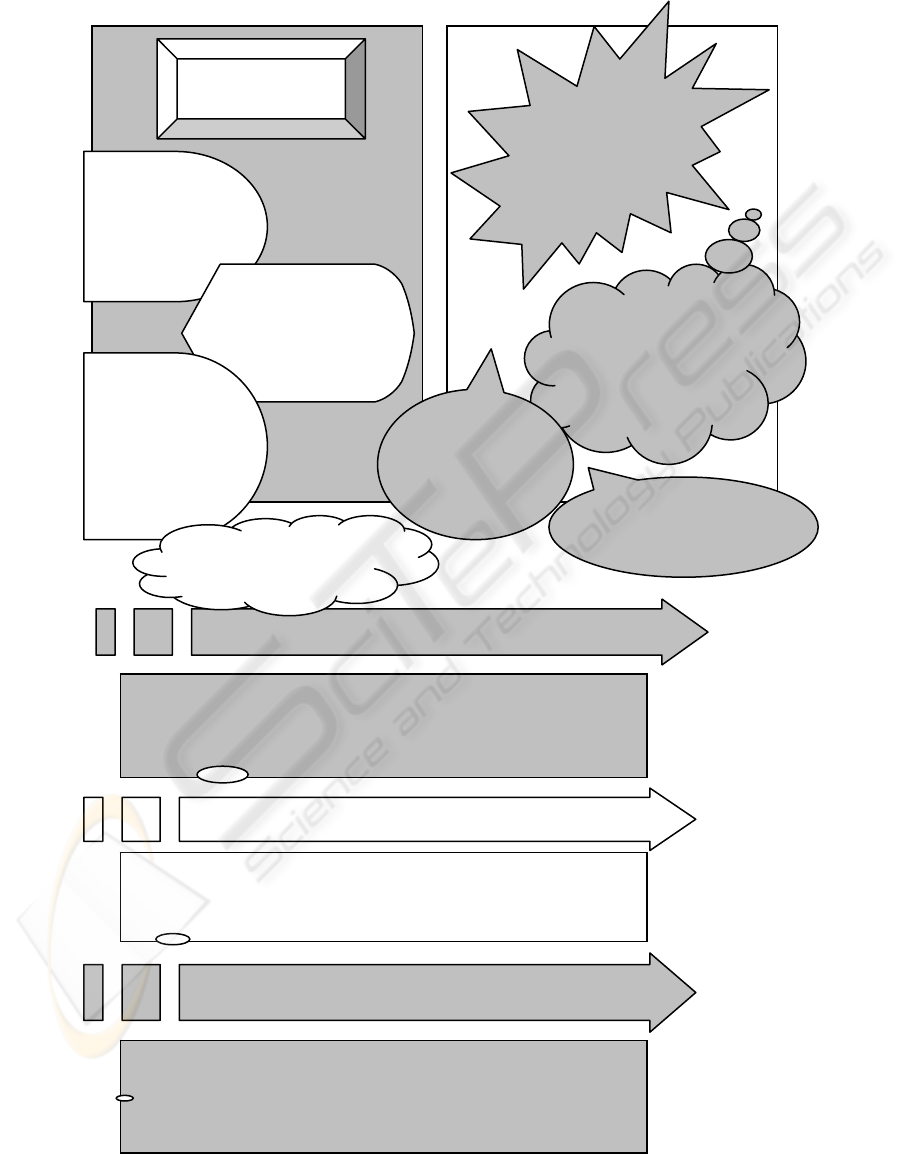

Figure Three – Human agency as the product of a social relationship and of a learning

process – the potential role of health care and of educational activities

SOCIAL

STRUCTURES

... are incarnate in

the PRACTICES

and products of

their members

... are both

MEDIUM and

PRODUCT,

ENABLING and

RESTRAINING

... and are

REPRODUCED

and

TRANSFORMED

by those activities

and practices

The SOCIAL

WORLD is

CONSTITUTED

by past and

ongoing human

activity

... and it does not exist

independently of the

conceptions of the

persons whose

activities constitute

them

HUMAN

AGENCY is this

power and

capacity to

interfere back

... and changes in

activity DO CHANGE

society

Implications in terms of the relationships that are to be promoted,

facilitaded and fostered

:

The more CONSTRUCTIVE, OPEN, DIALOGICAL, and DYNAMIC

the social relationships that we help to build, the more

TRANSFORMATIVE and the greater the DEVELOPMENTAL

POTENTIAL of our social communities and environments

In terms of an interpersonal relationship this means that:

The more a relationship helps to strengthen the AGENCY capacity of

each individual, the more transformative and developmental capacity

they will have

This capacity TO ACT and this AGENCY are the product of a

THERAPEUTICAL relationship and a LEARNING process

TO CARE = to help others learn to care for themselves

and, when possible, to care for others

TO LEARN = to participate in this collective experience which

is a transformation and a recreation developmental process

... possible implications

for Health and

Education?

156

8 Tele-care business-plan implications and policy making concerns

At the level of product/service definition the implications of these conceptual

perspectives can be substantiated and materialised through a specific business model.

Fundamentally, the integration of health care services provision with general and

broad range service provision, would be a way to illustrate this approach. The

justification for this is the following. As long as health care, in foundational terms,

may be paralleled with a therapeutic relationship as well as with a learning process,

and these, in turn, can be understood as a constructive social relation, then health

relations may be seen within a continuum of general social relationships. In business

terms this implies an integration of health care services with broad level services.

This option is consistent with current strategic theory which states that the more

complex the business environments and the market relations the more important it is

that there are broad level relationships between customers and the product or service

providers. Even when there are strong speciality areas where there has to be a focus in

specific core issues the diversification and integration within a broad range provision

scheme may be achieved through more or less structured and more or less formal

arrangements such as holdings, partnerships, associations, consortiums, protocols and

agreements. In terms of market segmentation and market positioning, there are

specific elements to take into account. Instead of segmenting in terms of service and

reductive views of a customer’s needs, it is more important to segment in terms of

point-of-sale or of groups of end clients. As an example, a tele-care service could be

integrated within a general service provision virtual platform that would integrate the

health services within a broad range of services. This way it could focus in a specific

client’s broad needs and offer diverse products that would share a common and

unique characteristic, that of closely and intimately understanding, and thus

responding adequately to, the specificity and idiosyncrasy of that client.

If we take, as an example, three types of clients such as an organisation, a private

home and a local community, we could devise a range of products that would respond

to the unique characteristics of these general-type clients and, simultaneously,

integrate health service provision among the list of offered services and products. This

certainly would be a more complex arrangement than a typical tele-care service

though it would have the critical advantage of using and applying a health as well as a

health care provision concept far more effective and thus potentially revolutionary in

terms of the effect that it may have in the daily lives of its clients.

For instance, this broad level service provision, within an organisation, could

integrate health related areas with general training, strategic thinking and

organisational learning and development consulting services. Within the setting of a

private home, it could integrate the health area with other activities such as

entertaining and educational, specialised and diverse advice, from financial to

psychological or career related, and also with more daily related services such as

shopping logistics, house cleaning or babysitting. In terms of a local community it

could promote health related services with citizen and e-government related issues.

These are just loose examples and they simply serve the purpose of illustrating

drastically innovative ways of promoting tele-care services.

In parallel to the exercise of focusing on the broad range needs of a particular

client-type it is essential to analyse the key characteristics of on-line service

157

provision. More important than actually providing the real services or products often

more crucial is to provide access to informed and critically assessed providers,

suppliers and strategic partners within this overall scheme. It would be more like an

intelligentsia activity, a network of trustworthy providers.

To stress the key point, this business strategy of providing tele-care, would offer,

sell, and also transport, become the vehicle of a specific idea and conception of what

health and health provision means and signifies. Both in market as well as in

marketing terms this represents a significant contribution both to the market in

general and also to the specific clients served by this approach. In business terms, it is

the possibility to generalise a client-type service provision that enables this idea to

become profitable both in financial terms and of the potential gain to the community

or society as a whole. In business terms, the closer example is the S.A.P. provision of

general type information systems, which are individually parameterised to respond to

specific situations. Nevertheless, S.A.P. is able to design, promote, sell and constantly

upgrade systems that deal with particular but generalisable client needs, such as

accounting, human resource management, finance, logistics or sales.

Health care provision is an activity of huge complexity and the present proposal

does not imply that we are taking a reductionist perspective. Quite the contrary,

instead of interpreting this complexity as a collection of almost infinite specialisations

and activities, it confronts this variety with what these activities mean from the

perspective of the patients themselves or of the potential patients and health service

users that we all are. From a daily life perspective, health and health care is related to

activities which we can improve and develop and also learn while we do it, as it is a

learning-by-doing process. These quality of life issues as well as the community

building mechanisms which enable their promotion are a central current concern of

policy makers. Both at local, regional, national and supra-national or international

level, these questions represent the core of the health related political discussion and

negotiation. If understood under this more general framework it is possible to grasp

and to acknowledge the importance of the issues raised by this paper. Because of

paper length limitations this can only be a general introduction to a potentially

revolutionary theory building and innovative practice within the health related and

computer supported service provision field.

9 Final words

The present paper’s contribution is to bring light into the complexity of health care

delivery services by questioning basic assumptions about health, in particular, but also

about the general way that societies organise and determine themselves. Broad level

issues are considered, ranging from the insights of the historical philosophical

development that conditions current perspectives of the computer ethics field, to the

contributions of critical realism and of philosophy of action. Throughout the paper the

double role of health and educational activities as crucial structuring sectors of society

is stressed and developed. The main argument is that health and education, at their

most general and essential level, are the potential bedrock for societal development.

Health care may thus be paralleled to the constructive social and therapeutic

relationship that helps each individual to reach their full potential. This social

158

experience is constitutivelly a learning activity and process. The double and parallel

role of health and education is further developed as a potential foundation for an

innovative and breakthrough health service delivery business. Tele-care is thus

explored as an activity which represents both the potential challenges and

opportunities of the information age as well as the philosophical assumptions that

shape current mentalities.

The present paper offers a road map that enables further development at conceptual

level as well as further application within both business strategic planning and at

policy making settings. And a final vote: that the uneasiness with which business and

managerial areas deal with philosophical and sociological analysis may be overcome

by effective and breakthrough mediations, as the exploring of the full potential of the

information age challenges crucially depends on researchers and practitioners role in

bridging these fields of knowledge. And this is what we call not only a technological

revolution but also a revolution of mentalities.

References

1. Archer, M., Bhaskar, R., Collier, A., Lawson, T. & Norrie, A.: Critical Realism.

Routledge, London (1998)

2. Argyris, C.: On Organisational Learning. Blackwell, Oxford, UK (1992)

3. Argyris, C., Schon, D.: Organisational Learning. Addison-Wesley: Reading,

Massachusetts (1978)

4. Bynum, T. (Ed.): Computers and Ethics. Oxford, Blackwell (1985)

5. Bynum, T., Rogerson, S. (Eds.): Computer Ethics and Professional

Responsibility. Oxford, UK, Blackwell (2004)

6. Davenport, Prusak: Working Knowledge, Harvard B.S. Press, USA (1997)

7. Gonçalves, J.: Fazer Filosofia – como e onde? (To do philosophy – how and

where?), Fac. Filosofia, U.C.P., Braga (1995)

8. Gorniak-Kocikowska, K.: The Computer Revolution and Global Ethics.

Ethicomp 95. Reprint in Science and Engineering Ethics, 2: 2 (1996) pp. 177-

190. Published in Bynum and Rogerson (2004)

9. Grun, B.: The Timetables of History: A Horizontal Linkage of People and

Events. Touchstone (1982)

10. Kearmally, S.: When economics means business. London: Financial Times

Management (1999)

11. Moor, J.: What is Computer Ethics? (1985) In: Bynum (1985)

12. Nonaka, I., Takeuchi, H.: The Knowledge-creating company, USA, Oxford

University Press (1995)

13. Senge, P.: The Fifth Discipline – the Art and Practice of the Learning

Organisation. USA, Century Business (1990)

159