ADVERTISING VIA MOBILE TERMINALS

Delivering context sensitive and personalized advertising

while guaranteeing privacy

Rebecca Bulander, Michael Decker, Gunther Schiefer

Insitute AIFB, University of Karlsruhe, Englerstr. 11,76128 Karlsruhe, Germany

Bernhard Kölmel

CAS Software AG,Wilhelm-Schickard-Str. 10-12, 76131 Karlsruhe, Germany

Keywords: Mobile Advertising, context sensitivity, data protection

Abstract: Mobile terminals like cellular phones and PDAs are a promising target platform for mobile advertising: The

devices are widely spread, are able to present interactive multimedia content and offer as almost

permanently carried along personal communication devices a high degree of reachability. But particular

because of the latter feature it is important to pay great attention to privacy aspects and avoidance of spam-

messages when designing an application for mobile advertising. Furthermore the limited user interface of

mobile devices is a special challenge. The following article describes the solution approach for mobile

advertising developed within the project MoMa, which was funded by the Federal Ministry of Economics

and Labour of Germany (BMWA). MoMa enables highly personalized and context sensitive mobile

advertising while guaranteeing data protection. To achieve this we have to distinguish public and private

context information.

1 INTRODUCTION

Advertising is defined as the non personal

presentation of ideas, product and services whereas

someone has to pay (Kotler & Bliemel, 1992).

Mobile or wireless

1

advertising uses mobile

terminals likes cellular phones and PDAs.

There are a couple of reasons why mobile

terminals are an interesting target for advertising:

• There are quite a lot of them: In Germany

there are more than 64 million cellular phones, a

number that exceeds that of fixed line telephones.

The average penetration rate of mobile phones in

Western Europe is about 83 percent (RegTP, 2004),

estimates for the worldwide number of cellular

1

Most authors use „wireless“ and „mobile“ as synonyms which

is strictly considered incorrect since wireless and mobile are

orthogonal concepts (Wang, 2003). “Mobile advertising” can

also denote advertising on a mobile surface (e.g. bus,

aeroplane, train), but we don’t use the term that way.

phones are far beyond one billion according to the

International Telecommunication Union (ITU).

• Mobile terminals are devices for personal

communication, so people carry such devices with

them most of the day which leads to a high

reachability of up to 14 hours a day (Sokolov, 2004).

Conventional advertising can reach its audience only

in certain timespans and situations (e.g. TV

commercials reach people when they are sitting in

their living room after work, newspaper ads are

usually read at breakfast time), but mobile

advertising can reach people almost anywhere and

anytime.

• Since each mobile terminal can be addressed

individually it is possible to realise target-oriented

and personalized advertising. Most conventional

advertising methods inevitably reach people not

interested in the advertised product or service.

• Mobile devices enable interaction. When one

receives an ad on his mobile terminal he can

immediately request further information or forward

it to friends.

49

Bulander R., Decker M., Schiefer G. and Kölmel B. (2005).

ADVERTISING VIA MOBILE TERMINALS - Delivering context sensitive and personalized advertising while guaranteeing privacy.

In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on e-Business and Telecommunication Networks, pages 49-56

DOI: 10.5220/0001410800490056

Copyright

c

SciTePress

• In the future most mobile devices will be

capable of presenting multimedia-content, e.g. little

images, movies or music sequences. This is

important if logos and jingles associated with a

certain brand have to be presented.

• The emerging mobile networks of the third

generation (e.g. UMTS) will provide enormous

bandwidths, so that until nowadays unthinkable

mobile services will be possible.

However there are also some serious challenges

to mention when talking about mobile advertising:

• Because of the permanently increasing

portion of spam-mail on the internet — statistics

state values far beyond 50 % (MessageLabs, 2004)

— there is the concern of this trend spilling over to

mobile networks. A survey recently conducted “[…]

indicates that more than 8 in 10 mobile phone users

surveyed have received unsolicited messages and are

more likely to change their operator than their

mobile number to fight the problem […]”

(International Telecommunication Union, 2005).

Spam-messages in mobile networks are a much

more critical problem, since mobile terminals have

relatively limited resources (bandwidth, memory for

storage of messages, computation power).

• The user of a mobile advertising application

will only provide personal data (e.g. age, marital

status, fields of interest) if data protection is

warranted. Especially when location based services

are able to track the position of users this causes

concerns about privacy (Barkhuss & Dey, 2003).

• Usability: Because of their small size mobile

terminals have a limited user interface, like small

displays or no full-blown keyboard. Thus a mobile

application should demand as few user entries as

possible. But the small display can be also

considered as advantage: only the text of the

advertisement will be displayed, nothing else will

distract the user.

• Expenses of mobile data transmission: today

the usage of mobile data communication is still very

expensive (e.g. about one Euro for 1 Mbyte data

traffic when using GPRS or UMTS, 0.20 Euro for

sending a SMS or 0.40 Euro for a MMS). This

hinders many people from using mobile devices for

internet research on products and services. Again

nobody wants to pay for advertisement, so the

advertiser should pay for the data transportation.

Within the project „Mobile Marketing (MoMa)“

we developed a system for mobile advertising which

takes all of the mentioned problems into account and

makes highly personalized advertising possible

while guaranteeing data protection.

The rest of this article is organized as follows:

the second chapter deals with related work. In

chapter three we describe the functionality,

architecture and business model of the MoMa-

system. Afterwards we discuss the different types of

context information in chapter four, before a

summary in the last chapter is given.

2 RELATED WORK

1.1 2.1 Mobile Advertising

The high potential of mobile advertising along with

its specific opportunities and challenges is widely

accepted in literature, see Barnes (2002), Tähtinen &

Salo (2004) or Yunos, Gao & Shim (2003) for

example. The latter article also discusses the

business models for mobile advertising by vendors

like Vindigo, SkyGo and AvantGo.

Today’s most common form of mobile

advertising is the delivery of ads via SMS (Barwise

& Strong, 2002), e.g. misteradgood.com by

MindMatics. SMS is very popular – in Germany

approximately 20 billion SMS were sent in 2003

(RegTP, 2003) – but the length of the text is limited

to 160 characters and images can’t be shown, so it

shouldn’t be the only used channel in a marketing

campaign (Dickinger et al., 2004).

Other more academic approaches for mobile

advertising are the distribution of advertisement

using multi-hop ad-hoc networks (Straub &

Heinemann, 2004, Ratsimor, 2003) or location

aware advertising using Bluetooth positioning (Aalto

et al, 2004). There is also the idea of advertising

using wearable computing (Randell & Muller,

2000).

Some systems even provide a monetary incentive

to the consumers for receiving advertisement like the

above mentioned misteradgood or the one described

by de Reyck & Degraeve (2003).

A very important concept in mobile advertising

due to the experience with spam-e-mails is

permission marketing (Godin, 1999): consumers will

only receive ads after they have explicitly opted-in

and they can opt-out anytime. Because a consumer

has to know a firm before he can opt-in it might be

necessary to advertise for a mobile advertising

campaign, see the three case studies in Bauer et al.

(2005) for example.

ICETE 2005 - GLOBAL COMMUNICATION INFORMATION SYSTEMS AND SERVICES

50

1.2 Context sensitive mobile

applications

The term context with regard to mobile applications

was introduced by Schilit, Adams & Want (1994)

and means a set of information to describe the

current situation of an user. A context sensitive

application makes use of this information to adapt to

the needs of the user. For mobile applications this is

especially important, since the terminals have a

limited interface to the user.

The most often cited example of context

sensitive applications are location based services

(LBS): Depending on the current position the user is

provided with information concerning his

environment, e.g. a tourist guide with comments

about the sights in the surrounding area (Cheverst,

2000). Technically this location context could be

detected using a GPS-receiver or the position of the

used base station (cell-ID).

But there are far more kinds of context

information than just location, see Schmidt, Beigl &

Gellersen (1999) or chapter four of this article for

example.

Other kinds of thinkable context sensitive

services depend on profile information. These

profiles can be retrieved with explicit support by the

user (active profiling) or when analysing earlier

sessions (passive profiling). Active profiling could

be implemented using a questionnaire, passive

profiling could apply data mining methods. Active

profiling means some work for the end user but is

completely transparent to him. Moreover not all

relevant information can be retrieved with the

needed accuracy using passive profiling, e.g. the age

of a person.

1.3 Empirical Results

Based on a survey (N=1028) Bauer et al. (2004)

tried to figure out the factors important for

consumer-acceptance of mobile advertising. Their

results indicate that the personal attitude is important

for the user acceptance of mobile advertising

campaigns. This attitude is mainly influenced by the

perceived entertaining and informative utility of

adverts, further also by social norms. “Knowledge

concerning mobile communication” and “attitude

towards advertising” didn’t show a strong effect.

Another survey conducted by Bauer et al. (2005)

was aimed at executives responsible for marketing

(N=101). More than one half already had experience

with mobile advertising campaigns, over 50 % of

those who didn’t intended to use the mobile channel

for advertising in the future. As most important

advantages “direct contact to customers” (87 %),

“ubiquity” (87 %), “innovation” (74 %),

“interactivity” (67 %) and “viral effects” (38 %)

were considered. As disadvantages “high effort for

implementation” (59 %), “limited creativity” (56 %),

“untrustworthy” (43 %), “target group can’t be

reached” (11 %) and “lack of consumer acceptance”

(8 %) were mentioned.

An often cited empirical study in the field of

mobile advertising is the one conducted by Barwise

& Strong (2002): one thousand people aged 16-30

were chosen randomly and received SMS-adverts

during a trial which lasted for 6 weeks. The results

are very encouraging: 80 % of the test persons didn’t

delete the adverts before reading them, 74 % read at

least three quarters of them, 77 % read them

immediately after reception. Some adverts included

competitions which generated an average response

rate of 13 %. There was even a competition where

41 % of those who responded did so within the first

minute. Surprisingly 17 % of test persons forwarded

one or more text adverts to a third party, which

wasn’t intended by the research design. Another

result is that respondents felt that receiving three text

messages a day was “about right”.

3 DESCRIPTION OF THE

MOMA-SYSTEM

1.4 Overview

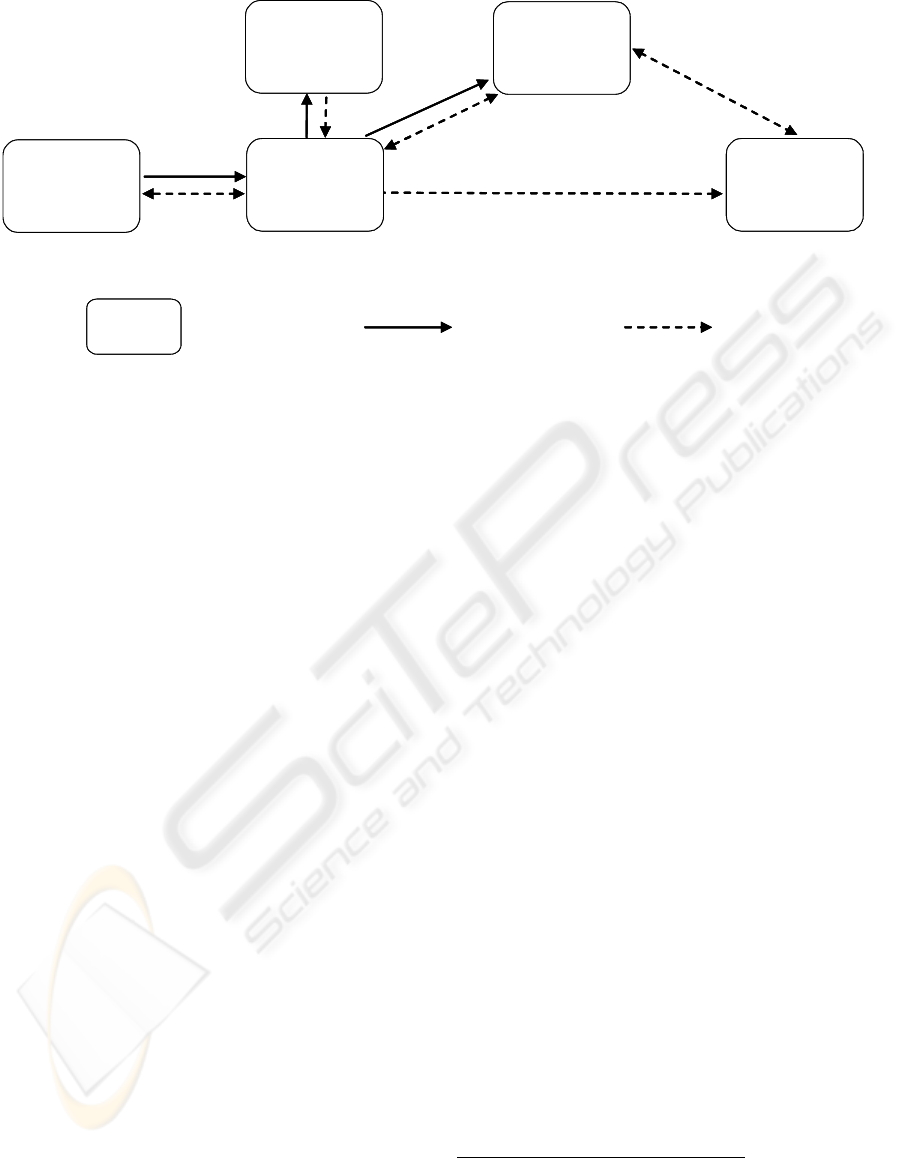

The basic principle of the MoMa-system is

illustrated in figure 1: The end users create orders

according to a given catalogue whereas the client

software automatically queries needed context

parameters. The catalogue (see figure 2 for a

screenshot) is a hierarchical ordered set of possible

product and service-offers which are described by

appropriate attributes: on the uppermost level we

may have “travelling“, “sport & fitness” or

”gastronomy” for example, whereas the latter could

subsume categories like “pubs”, “restaurants” or

“catering services”. Each category is specified by

certain attributes, in the gastronomy example this

could be “price level” and “style”. When creating an

order the client application will automatically fill in

appropriate context parameters, e.g. “location” and

“weather”: the gastronomy facility shouldn’t be too

far away from the current location of the user and

beer gardens shouldn’t be recommended if it’s

raining.

ADVERTISING VIA MOBILE TERMINALS - Delivering context sensitive and personalized advertising while

guaranteeing privacy

51

MoMa-

System

Order 1

Order 2

Order m

Matches

Context Information

Offer 1

Offer 2

Offer n

…

…

advertisersend users

Notifications

MoMa-

System

Order 1

Order 2

Order m

Matches

Context Information

Offer 1

Offer 2

Offer n

…

…

advertisersend users

Notifications

Figure 1: Basic principle of the MoMa-system

On the other side the advertisers put offers into

the MoMa-System. These offers are also formulated

according to the catalogue. When the system detects

a pair of a matching order and offer the end user is

notified. Then he can decide if he wants to contact

the advertiser to call upon the offer, but this is

beyond the scope of the MoMa-system.

Figure 2: Screenshot of client application on Symbian OS

(catalogue view)

The end user only gets advertising messages

when he explicitly wants to be informed about

orders matching certain criterions. He is anonymous

with regard to the advertisers as long as he doesn’t

decide to contact them. The later described

architecture of the system supports the employment

of a trust third-party as mediator between end users

and MoMa, so even transaction-pseudonymity with

regard to the operator of MoMa can be achieved.

1.5 Business model

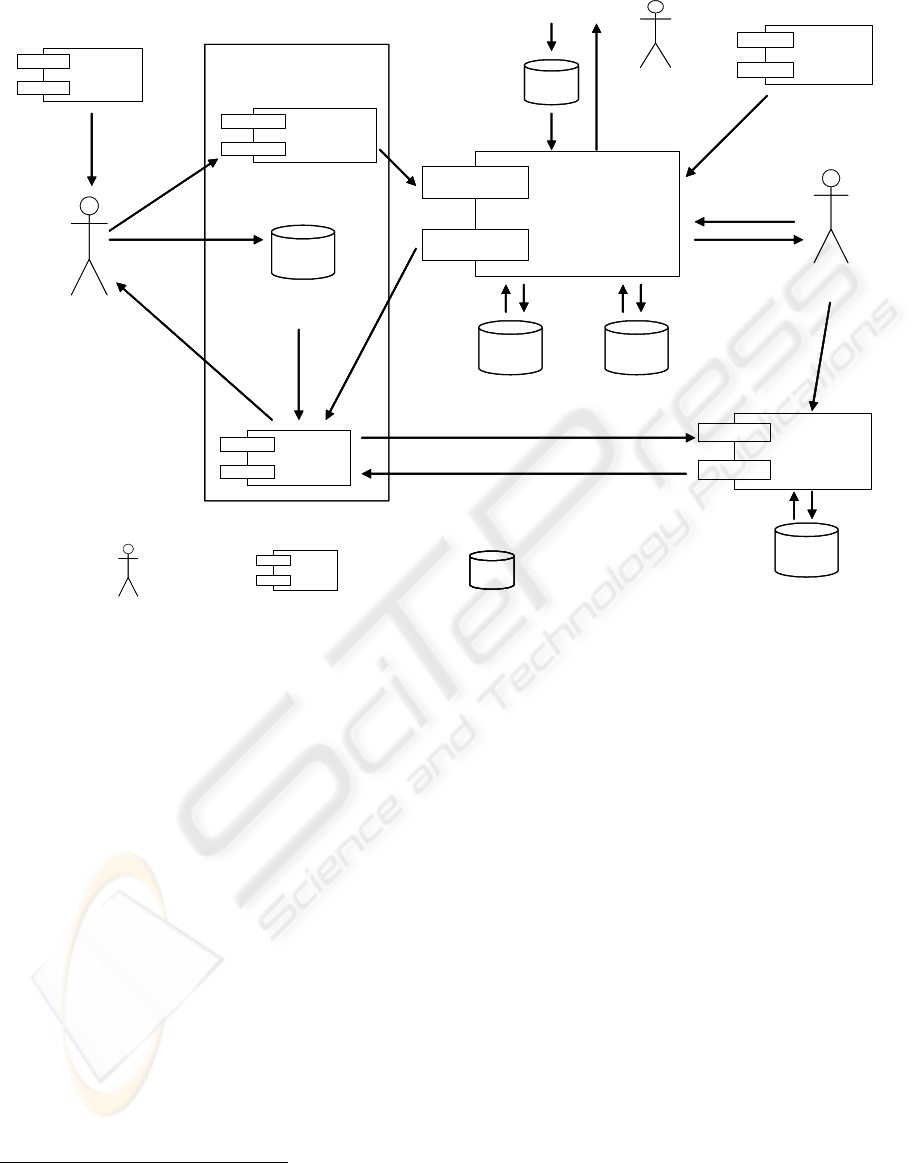

The flows of money and information between the

different roles within the business model of MoMa

are depicted in figure 3. The roles are: advertiser,

MoMa-operator, context-provider, mobile network

operator, trusted party and end user.

For the end user MoMa is free, he only has to

pay his network provider for the transferred data

when he submits an order to the system. Since the

data volume generated when sending one order is

less than 1 Kbyte, these costs are almost negligible.

On the other side the advertisers only have to pay for

actual contacts. The price for one contact depends on

the used category of the catalogue, for example one

contact of the category “real estate” may be more

expensive than a “lunch break”-contact. If the

number of “lunch break”-offers should explode, the

price for that category could be adjusted. The price

for one contact has at least to cover the

communication-costs for the notification of the end

user.

Another source of revenue for the MoMa-

operator is providing statistical analyses about what

kind of products and services the users of the

MoMa-system are interested in. The MoMa-operator

has to pay for the services of the trustworthy party

and the context-providers.

When introducing a system like MoMa there is

the well known “hen-and-egg”-problem of how to

obtain the critical mass of advertisers and end users:

without a certain number of advertisers there won’t

be enough interesting offers but without offers

MoMa isn’t interesting for end users. However

without many end users MoMa isn’t interesting for

advertisers. To overcome this problem there is the

possibility of automatically putting offers from well-

established eCommerce-platforms into the system

without charging the operators of those platforms.

Since many of them offer a webservice-interface this

can be achieved without much effort.

ICETE 2005 - GLOBAL COMMUNICATION INFORMATION SYSTEMS AND SERVICES

52

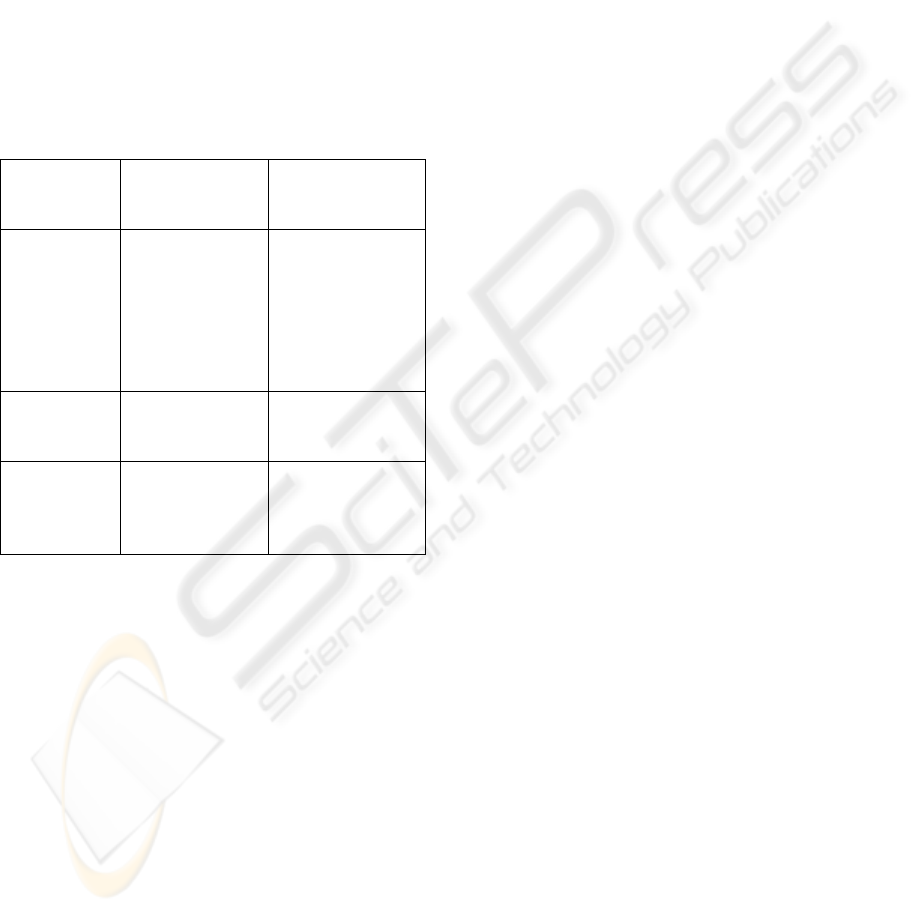

1.6 Architecture and technical

details

Each end user of the MoMa-system (see figure 4)

has an unique user-id and at least one general and

one notification profile. The general profile contains

information concerning the user which could be

relevant for the creation of an order, e.g. age, family

status, fields of interest. A notification profile

describes how (SMS/MMS, e-mail, text-to-speech,

etc) an user wants to be notified when an offer

matching one of his orders is found; this notification

mode can depend on the current time, e.g. text-to-

speech-calls to phone number A from 9 a.m. till 16

p.m. and to phone-number B from 16 p.m. till 20

p.m., send e-mail-message else. The instances of

both kinds of profiles can be stored on a server of

the anonymization service, so they can be used on

different terminals of an user. Only the notification

profiles have to be readable for the anonymization

service, the general profiles can be encrypted in a

way only the user can decrypt them.

For the creation of an order X the user chooses

one of his general and notification profile each and

specifies what he desires using the categories and

attributes of the catalogue. In doing so, single

attribute values will be looked up automatically in

the chosen general profile respective the available

private context parameters if applicable. Please note:

the order X itself contains no declaration about the

identity or end addresses of the user. The user-ID,

the index of the chosen notification profile and a

randomly generated bit string are put together and

encrypted

2

, the resulting cipher text be denoted with

C. The pair {X, C} is sent to the anonymizer which

forwards it to the core system. This loop way

ensures the MoMa-operator cannot retrieve the IP-

or MSISDN-address of the order’s originator.

Should a private context parameter change while an

order is active (e.g. new location of user) the

updated X’ along with the old C will be send to the

core server, where the old order X can be looked up

by C and be replaced with X’.

The advertiser defines his offer Y using the

catalogue and transmits it to the MoMa-Server

directly. Furthermore he deposits different templates

for notifications of end users on the publishing &

rendering-server.

Triggered by events like new/updated orders and

offers or changed public context parameters the

MoMa-server tries to find matching pairs of orders

and offers. For each match {{X, C}, Y} found C

along with the ID of Y will be sent to the resolver-

component of the trustworthy party. Here C is

decrypted so the notification profile can be looked

up to request the needed notification from the

publishing-server. This message will be dispatched

to the given end address.

If there is already a matching offer in the

database, the users immediately gets an answer, so

we could consider this as pull-advertisement; if the

matching order enters the system after the offer, the

notification of the user is a push-advertisement.

2

For the architecture it doesn’t matter if a symmetric or

asymmetric encryption algorithm is used. Symmetric

encryption is favourable in terms of the needed computation

power (which may be limited on a mobile device), but requires

a secure channel for the initial exchange of the key.

Figure 3: Money and data flows of the MoMa-business model

End user

Role Money flow Data flow

Legend:

Trusted

Third-party

Advertiser

MoMa-

Operator

Context

Provider

End userEnd user

Role Money flow Data flow

Legend:

Trusted

Third-party

Trusted

Third-party

AdvertiserAdvertiser

MoMa-

Operator

MoMa-

Operator

Context

Provider

Context

Provider

ADVERTISING VIA MOBILE TERMINALS - Delivering context sensitive and personalized advertising while

guaranteeing privacy

53

Using context information we can amend the orders

in a “smart” way, so MoMa can be denoted as

combined smart push & pull approach.

The advertisers don’t have access to the personal

data of the end users, in particular they can’t find out

about the end addresses to send unsolicited messages

and have no physical access to components of the

system where addresses are stored. Even the

operator of MoMa only sees the cipher text C. This

ciphertext C is different for each order, even if two

orders have the same user ID and use the same

notification profile, because of the random

information included. Thus C can be considered as

transaction pseudonym, which is the most secure

level of pseudonymity (Pfitzmann & Köhntopp,

2000)

3

.

3

Transaction pseudonyms are more secure than other kinds of

pseudonyms (relation or role pseudonyms, personal

pseudonyms), since it is less likely that the identity (or end

address) of the user behind a pseudonym is revealed.

4 DIFFERENT CLASSES OF

CONTEXT INFORMATION

The anonymization of the orders requires the

distinction between public and private context

information (see columns c

i1

, c

i2

in table 1):

• Private context parameters are retrieved by

the mobile terminal and its sensors or the mobile

terminal is at least involved. Thus private context

parameters can’t be retrieved anonymously but they

can be processed anonymously. Examples: position,

background noise level, temperature, calendar,

available technical resources like display size or

speed of CPU.

• Public context information can be retrieved

without knowledge about the identity of the

respective user. Examples: weather, traffic jams,

rates at the stock exchange.

For the reasonable processing of some

parameters of the public context it might be

necessary to know about certain private context

parameters, e.g. the weather in a given city is a

public context parameter, but one has to know the

Role Module Datastore

Core-System

End user

Provider

Operator

Orders

Offers

Trustworthy party

Templates,

Product-Infos

Notification-

Profiles

Resolver

Anonymizer

Catalogues

Private

Contexts

Public

Contexts

Publishing &

Rendering

statistics

statistics

Weather, traffic-

situation, ...

administrates

Location,

calendar,

noise-level,

...

matches

offers

orders

Notification

dispatching

Offer-Index, Notification-Type

Notification-Message

Profiles

Infos concerning

offers

Legend:

Role Module DatastoreRoleRole ModuleModule DatastoreDatastore

Core-System

End user

Provider

Operator

Orders

Offers

Trustworthy party

Templates,

Product-Infos

Notification-

Profiles

Resolver

Anonymizer

Catalogues

Private

Contexts

Public

Contexts

Publishing &

Rendering

statistics

statistics

Weather, traffic-

situation, ...

administrates

Location,

calendar,

noise-level,

...

matches

offers

orders

Notification

dispatching

Offer-Index, Notification-Type

Notification-Message

Profiles

Infos concerning

offers

Legend:

Figure 4: Architecture of the MoMa-system

ICETE 2005 - GLOBAL COMMUNICATION INFORMATION SYSTEMS AND SERVICES

54

location of the user to look up the weather in the

right city.

Furthermore context parameters can be

characterised by different degrees of variability

(rows c

1j

, c

2j

, c

3j

in table 1):

• Static context parameters have never or very

seldom to be updated. Examples: gender or mother-

tongue.

• Semistatic context parameters changes have

to be updated but not very often (several weeks or

years). Examples: age, family status.

• Dynamical context parameters change often

or even permanently. Example: current location of a

user, surrounding noise level.

Table 1: Different classes of context

Context

dimension c

ij

(examples)

public c

i1

private c

i2

c

1j

Static

c

11

(currency,

timestamp

format,

frequency of

radio access

network)

c

12

(gender, date of

birth)

c

2j

Semistatic

c

21

(season, bathing

season)

c

22

(salary, job,

number of kids)

c

3j

Dynamic

c

31

(weather, traffic

situation,

delayed train)

c

32

(location, display

size, surrounding

noise level)

When combining these two classification

schemes we obtain the six classes shown in table 1.

Based upon these six classes we can give statements

how to retrieve the respective context parameters:

• Public static context parameters (c

11

) will be

determined via configuration when installing a

MoMa-System.

• Public semistatic context parameters (c

21

)

will be set manually by the MoMa-operator or

derived from rules depending on the date if

applicable.

• Public dynamic context parameters (c

31

) will

be queried by the MoMa-operator from special

context providers.

• Private static and semistatic parameters (c

12

,

c

22

) have to be determined using active profiling.

According to their definition these parameters

change never or very seldom so it isn’t much work

for the end user to keep them up to date.

• The parameters of the private dynamic

context (c

32

) have to be determined for each order by

the mobile terminal of the end user.

5 SUMMARY

The presented system in this article enables context

sensitive mobile advertising while guaranteeing a

high level of privacy. To achieve this, the distinction

of private and public context parameters is

necessary. An end user will only receive

personalized offers when he defines orders so there

is no danger of spamming. The costs for the

transmission of the ads are covered by the MoMa-

operator respective the advertisers. Since mobile

terminals have a limited user interface the MoMa-

client-application is designed in a context sensitive

manner to assist the end user. There are also

different kinds of profiles to support the usability.

The industry-partners of the MoMa-consortium

plan to utilize the results of the project within the

scope of the Soccer World Championship 2006.

REFERENCES

Aalto, L., Göthlin, N., Korhonenm, J. & Ojala, T., 2004.

Bluetooth and WAP Push based location-aware

mobile advertising system. In MobiSYS ’04:

Proceedings of the 2

nd

international conference on

Mobile systems, applications, and services, Boston,

USA. ACM Press.

Bauer, H.H., Reichardt, T., & Neuman, M.M.

Bestimmungsfaktoren der Konsumentenakzeptanz von

Mobile Marketing in Deutschland – Eine empirische

Untersuchung (in german). Institut für

Marktorientierte Unternehmensführung (IMU),

Universität Mannheim, 2004.

Bauer, H.H, Lippert, I., Reichardt, T., & Neumann, N.N.

Effective Mobile Marketing – Eine empirische

Untersuchung (in german). Institut für

Marktorientierte Unternehmensführung (IMU),

Universität Mannheim, 2005.

Barkhuss, L. & Dey, A., 2003. Location-Based Services

for Mobile Telephony: a study of users’ privacy

concerns. In INTERACT 2003, 9th IFIP TC13

International Conference on Human-Computer

Interaction.

Barnes, S., 2002. Wireless digital advertising: nature and

implications. In International journal of advertising,

21, 2002, pages 399-420.

Barwise, P. & Strong, C., 2002: Permission-based mobile

advertising. In Journal of interactive Marketing, vol

16, no 1.

Cheverst, K., 2000. Providing Tailored (Context-Aware)

Information to City Visitors. In Proc. of the

conference on Adaptive Hyper-media and Adaptive

Webbased Systems, Trento.

ADVERTISING VIA MOBILE TERMINALS - Delivering context sensitive and personalized advertising while

guaranteeing privacy

55

Dickinger, A., Haghirian, P., Murphy, J. & Scharl, A.,

2004. An investigation and conceptual model of SMS

marketing. In Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii

international conference on system sciences 2004.

IEEE.

Godin, S., 1999. Permission Marketing: Turning strangers

into friends, and friends into customers. Simon and

Schuster.

International Telecommunication Union (ITU), 2005. First

empirical global spam study indicates more than 80

percent of mobile phone users receive spam.

http://www.mobilespam.org.

Kotler, P. & Bliemel, F., 1992. Marketing Management.

Poeschel, Stuttgart.

MessageLabs, 2004. Intelligence Annual Email Security

Report 2004.

Pfitzmann, A. & Köhntopp, M., 2000. Anonymity,

unobservability, and pseudonymity: A proposal for

terminology. In Designing privacy enhancing

technologies — International workshop on design

issues in anonymity and unobservability. Springer,

Heidelberg.

Randell, C. & Muller, H., 2000. The Shopping Jacket:

Wearable Computing for the consumer. In Personal

Technologies. Vol 4, no 4, Springer.

Ratsimor, O., Finin, T., Joshi, A. & Yesha, Y.: eNcentive:

A framework for intelligent marketing in mobile peer-

to-peer environments. In Proceedings of the 5th

international conference on electronic commerce,

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. ACM Press, New York.

RegTP, 2003. “Jahresbericht 2003 – Marktdaten der

Regulierungsbehörde für Telekommunikation und

Post”. German Regulatory authority of

telecommunication and postal system.

de Reyck, B. & Degraeve, Z., 2003: Broadcast scheduling

for mobile advertising. In Operations Research, Vol

51, No 4.

Schilit, B. N., Adams, N. I. & Want R., 1994: Context-

Aware Computing Applications. In Proc. Of the

IEEE Workshop on Mobile Computing Systems and

Applications, Santa Cruz, Ca, 1994. IEEE Computer

Society.

Schmidt, A., Beigl, M. & Gellersen, H.-W., 1999. There is

more to context than location. In Computer and

Graphics, vol. 23, no. 6.

Straub, T. & Heinemann, A., 2004: An anonymous bonus

point system for mobile commerce based on word-of-

mouth recommendations. In Proc. of the 2004 ACM

symposium on Applied computing, Nicosia, Cyprus.

ACM.

Sokolov, D., 2004. Rabattstreifen per SMS. Spiegel

Online, 20.10.2004.

Tähtinen, J. & Salo, J., 2004. Special features of mobile

advertising and their utilization. In Proceedings of the

33rd EMAC conference, Murcia, Spain. European

Marketing Academy.

Yunos, H., Gao, J. & Shim, S., 2003. Wireless

advertising’s challenges and opportunities. IEEE

Computer, Vol. 36, no 5.

Wang, Z., 2003. An agent based integrated service

platform for wireless and mobile environments.

Shaker.

ICETE 2005 - GLOBAL COMMUNICATION INFORMATION SYSTEMS AND SERVICES

56