Modelling the role of e-learning in developing

collaborative skills

David King, Sharon Cox and Richard Midgley

Department of Computing, University of Central England, Birmingham.

Abstract. This paper presents a model to assist in planning the use of e learning

to support the teaching and learning of transferable skills needed to support

collaboration. The model is derived from the practical experience of tutors

teaching technical undergraduates in a UK university. The findings suggest a

three stage model taking a student through participation and collaborative

engagement in the teaching material, learning by reflection upon its content in

groups, and finally an innovative method of supporting their comprehension of

the skills being taught.

1 Introduction

E-learning offers the potential to use technology as a means to take a student from

being a passive recipient of knowledge to becoming an active learner. This should

lead to more effective learning:

‘E-learning can empower the learner as they take control and responsibility for

their learning.’ [4].

Active participation and engagement in the learning process is especially important

in the teaching and learning of transferable skills: skills that are not confined to any

particular job or subject discipline, but can be transferred from one to another. These

includes skills such as communication and team working which are essential to

effective collaboration, within and between organisations. To successfully acquire

these skills requires a student to move beyond passive knowledge acquisition to

actively changing their behaviour through application of the skills; becoming

‘unconsciously competent’ through the embedding and internalising of transferable

skills.

This paper proposes a model that sets out the requirements to assist tutors in the

use of e-learning systems to support the teaching and learning of transferable skills.

The model addresses two aspects: firstly, the prerequisites for a student’s use of an

e-learning system; and secondly, how that system can encourage a student to become

an active learner, engaged in skill acquisition.

The paper considers first the prerequisites for the use of e-learning to support

teaching and which are discussed with reference to appropriate literature. This is

followed by a review of the findings from interviews conducted at a UK university to

King D., Cox S. and Midgley R. (2005).

Modelling the role of e-learning in developing collaborative skills.

In Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Requirements Engineering for Information Systems in Digital Economy, pages 79-88

DOI: 10.5220/0001423300790088

Copyright

c

SciTePress

understand the specific use of e-learning to support the teaching and learning of

transferable skills. The findings are developed into a model demonstrating the role of

e-learning systems. The paper concludes with an evaluation of the model and a

discussion for further work.

2 E-Learning as an Electronic Resource

Before a student can progress to applying knowledge, they must first be taught that

knowledge. E-learning is now well established in supporting the teaching process, and

is becoming more sophisticated in what it has to offer.

2.1 The Simplest Implementation

In Higher Education, small group tuition was the traditional approach to learning.

This was intended to consolidate the knowledge taught through large group lectures.

The initial use of computers was to supplement this process by providing online

access to course information and source material [10].

The use of e-learning as a repository for materials is not always successful. Issroff

& Scanlon (2002) cite the example of history students who were insufficiently

computer literate to use their support site as intended and instead printed out all the

material.

Even when effective in making materials available to students, this use of e-

learning has the danger that students may see the online materials as complete and

ignore the need for additional reading and thinking around the subject matter [17].

Poorly structured course material exacerbates this problem. This is often the case

when existing teaching materials are simply transferred to a computer. The resulting

elementary ‘electronic page turner’ encourages passive learning; any interactive

element that may have been added in lectures or seminars having been lost [7]. An

example of this type of problem was reported by Conrad (2004) who found several of

the more flamboyant tutors were no longer able to use gestures to animate their

lectures because this would take them out of the fixed camera shot. These tutors

found it difficult to communicate effectively in the new medium and engage their

students. The students’ performance suffered as a consequence.

2.2 Improving Implementations

The minimal use of e-learning highlights three issues to be resolved: ensuring that

students are computer literate enough to use the technology; that the materials are

appropriate to the teaching needs; and that the materials are engaging and can sustain

interaction. These issues are briefly discussed in the following sections.

80

Student Computer Literacy As computers are used more widely in education, as

well as society at large, so the issue of student computer literacy diminishes. This is

significant because studies in the use of e-learning have shown that those students

with more computer experience achieve better results than their peers [5]. Indeed,

students may now have a greater awareness of computer technology than their tutors

[9].

Conversely, there are studies are reporting problems arising from over-confidence

among students. Howard-Jones & Martin (2002) found a negative correlation between

computer skills and learning outcomes. Their conclusion was that the less confident

students were taking more time and care over their answers. Thus the implementers of

an e-learning system need to ensure that the users have the appropriate skill level to

use the system.

Material Design When documents are transferred to a computer format, it is

suggested that they be ‘re-purposed’ [15]; [14]. This is to best exploit the different

potential of the medium, especially the non-linear and non-sequential nature of

hypertext documents.

A concern arising from the use of hypertext is that users can become ‘lost in

hyperspace’. One potential remedy is the use of previews on links. Cress & Knabel

(2002) looked at the use of these and found that previews of links helped browsing.

The users also showed increased learning, probably because the preview introduced

the next concept in a few words. So adaptation of teaching material to the new

medium, even of passive teaching material, can lead to improved learning outcomes.

Engaging the Students E-learning supports engagement on two levels.

The first is that it is easier for a student to access teaching materials. A student can,

to a degree defined by the course designer, choose their own time, place and pace of

study [18]. This flexibility also makes it easier for a student to miss their studies. E-

learning systems, however, provide facilities to monitor use and enable actions to be

taken with regard to students who do not access the materials. This ‘policing’ role is

important as there is a strong correlation between ‘attendance’ and successful learning

outcomes [2]. However, a record that a student has accessed an on-line resource for a

period of time has the same limitations as a record of a student attendance at a lecture;

it is insufficient evidence of participation in the learning process.

The second method of improving engagement is to provide engaging materials.

One example is recorded in a quantitative analysis of the results in teaching remedial

mathematics to South African technical undergraduates using interactive computer

tutorials by Frith et al (2004). They reported results better than those achieved by the

previous classroom lecture based approach. In the UK, [1] reported a similar

improvement when teaching formal reasoning to undergraduates following a move

from paper based tuition to an online tool. The interactive materials were encouraging

the students to ‘play’ with the concepts they were being taught, so consolidating their

learning and producing improved learning outcomes.

81

Supporting Students This section has shown through the increasing sophistication of

implementations of e learning that there are three factors which form the underlying

requirements for its effective use learning in teaching. If students are capable of using

an e learning system, use material designed to exploit that system and have these two

factors come together to encourage student engagement, then improved learning

outcomes are reported when teaching direct, subject specific skills. E-learning

technology can be used to support the student as a passive recipient of knowledge.

3 E-Learning as an Enabler of Skill Development

Transferable skills require more then just the acquisition of knowledge through

teaching. These skills should result in a change in the behaviour of a student and so a

student needs the opportunity to practice the skills, and the opportunity to reflect upon

that practice. E-learning is claimed to support both of these needs; helping the student

be an active learner. The rest of this paper considers the actual use of e-learning in a

university to determine the efficacy of e-learning when supporting the teaching and

learning of transferable skills, and establish guidelines for its use in that role.

3.1 E-Learning in Use

A study of the use of e-learning was conducted at The University of Central England

in Birmingham (UCE) which has been praised by JISC (the Joint information Systems

Committee) for its use of e-learning.

Following a general survey of staff at the university about their priorities in using

e-learning, a more detailed survey was conducted within the Department of

Computing where e-learning technologies have been used for twelve years. Staff were

interviewed as to how and why they use, or do not use, e-learning for teaching

transferable skills.

Narrowing the choice of subject discipline allowed the study to explore the issue of

student engagement in detail. Computing was chosen because students on technical,

vocational courses are not as receptive to the teaching of ‘soft’ transferable skills

because they believe they are already studying all the employment skills that they

require [16]; [6].

3.2 Summary of Findings

From the department survey, the most influential factor in a tutor’s choice to use e-

learning or not was the ease of communication with students that it would permit. A

variety of tools were used, according to the situation including e-mail, general on-line

notice boards, module specific notice boards and discussion forums.

Using the e-learning system as a repository for the taught materials was universally

accepted within the culture of the department, enabling students to access material

themselves without tutor intervention. This was also recognised as a particular benefit

for part-time students who found it difficult to attend on-site, and the numbers of part-

82

time students on a module was a factor for some tutors when defining the blend of

e-learning to be used within their modules.

The tutors also liked the flexibility in the timing of release of material to students

afforded by e-learning. Many tutors used this as a mechanism to maintain students’

engagement with the module, only releasing support material after the formal lecture

or exercise were it was applicable.

All tutors used the notice board for course related messages in recognition of its

effectiveness against the other forms of general communication with their students.

The notice board was also used for general feedback on assignments, while for

individual feedback on assignments e-mail was preferred. Most modules had been

arranged so that feedback could be delivered electronically as this saved time and

enabled formative feedback to be delivered promptly enabling a student to act on it

during the module. Some tutors had developed this use of e-learning tools to include

on-line discussions as part of their course: some formally moderated by the tutor, and

others for the students’ use so as to encourage their independent reflection on the

course materials.

In addition to the positive factors encouraging the use of e-learning, there were

those that discouraged it. There was a general avoidance of greater use of e-learning

owing to the time required to develop appropriate material. This was exacerbated

when considering transferable skills because of the amount of time e-moderating

group work was known to take. However, the most important factor in deciding to use

online team work was a tutor’s familiarity with the technology involved. The

introduction of Moodle, an open source virtual learning environment, is regarded

favourably, encouraged by the positive experiences with online exercises and the high

levels of student engagement reported during its pilot implementation. In addition,

many tutors commented on the pedagogical opportunities they intended to exploit

with the tool set available within Moodle.

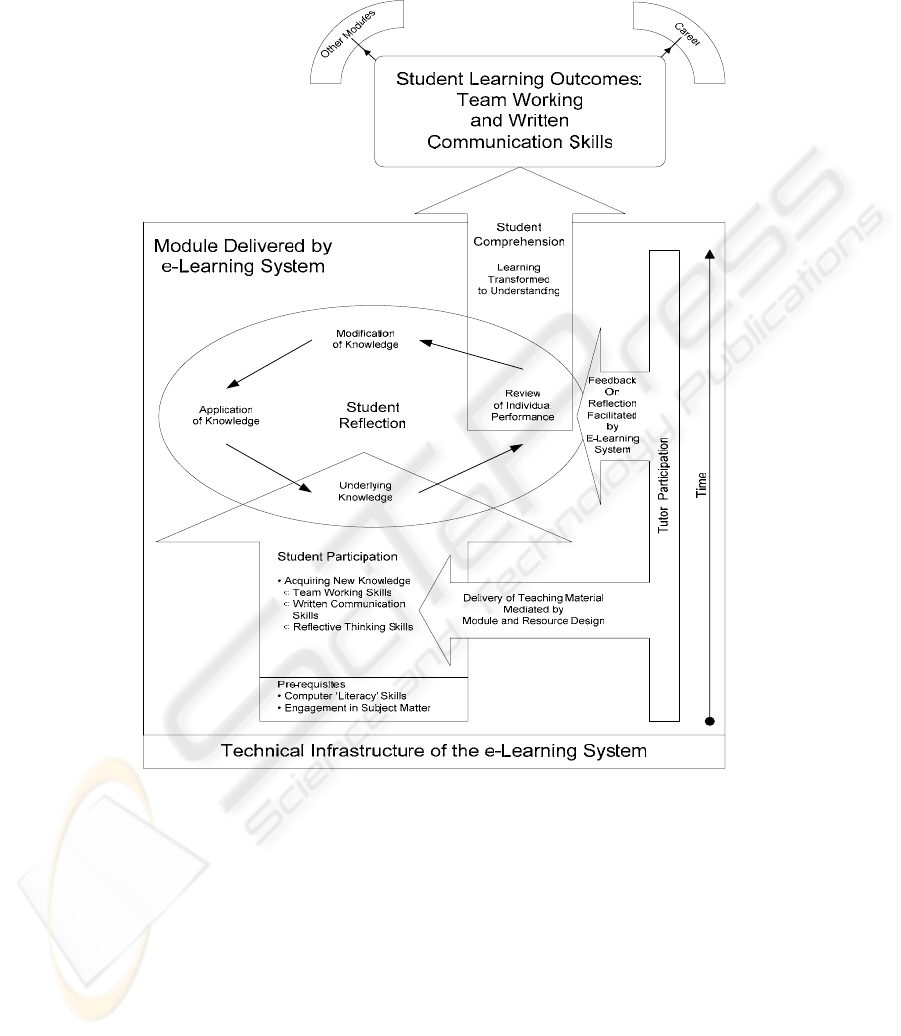

Developing the E-Learning Model The findings were then mapped to produce a

model shown in Figure 1. The boundary of the model is determined by the course

module delivered using the e-learning environment. The reliability of the technical

infrastructure underpins this environment and is shown along the bottom of the

model.

The key factor identified to the successful use of e-learning was its ability to enable

communication between tutor and student. This is shown in the framework by the

tutor participation block. The tutor can distribute appropriate material in a flexible

manner to support the delivery of teaching to the students. The consolidation of that

teaching later in the module is supported by other e-learning tools that allow a tutor to

provide feedback to a student on their learning.

The student experience was initially defined in two stages: teaching, or student

participation, and learning, or student reflection. Pre-requisite to successful student

participation is their ability to use the e-learning system, computer literacy, and the

ability to work with the teaching materials, engagement. In this example, the

transferable skills of team working and written communication can then be taught,

supplemented by the teaching of reflective thinking so that a student can reflect upon

their learning.

83

The critical element in learning transferable skills is the reflection process. It is

reflection that allows a student to internalise the taught material and practice the

changes in behaviour that should be a consequence of the learning. All tutors

described the process in terms of Kolb’s experiential learning model [13], albeit

without using Kolb’s terms. The tutors’ words were used in the framework. It was

during these discussions that a further distinction was developed relating to

transferable skills that distinguish them from other skills: the learning outcomes are

transferable too.

The Position of Learning Outcomes Conventional models of teaching and learning

have learning outcomes within the teaching module; this model has the learning

outcomes produced outside the originating module.

The module is aiming to teach transferable skills, yet if the learning outcomes are

retained within the module it is possible for a student to be a strategic learner and only

learn sufficient to pass that module. If the learning outcomes are placed outside the

module, and are assessed in other modules, then the student is forced to engage with

the material in an active manner and apply the learning as a transferable skill.

E-learning enables this because of the flexibility in communication between tutor and

student. The communication can be across modules as well as within modules, and

hyperlinks can enable access to the appropriate material from any module.

The role of e-learning The model takes a student through three stages: participation,

reflection and comprehension. E learning used within a formal module can directly

assist with the first two of these in the delivery of material to support the teaching and

delivery of feedback to support reflection. However, the final stage, student

comprehension, takes the student outside of that module, and represents a student’s

understanding that the skill they have acquired is applicable outside the module. This

is a new role for e learning, to provide explicit links across modules.

84

4 Evaluation of the Model

Fig. 1. A Framework that Demonstrates the Role of E-Learning in the Teaching of Transferable

Skills

Figure 1 presents a three-stage model showing the role of e-learning tools as applied

to the teaching and learning of transferable skills. Underpinning the model is the

reliability of the technical infrastructure of the e-learning system itself. The current

semester based approach in Higher Education affords little time for recovery from

system failure.

This framework is similar to other models of teaching and learning, for example, it

incorporates Kolb’s experiential model; but it goes further in taking a student’s

85

learning outcomes outside the original module. This shows that the learning

outcomes, as well as the skills, are transferable, and so relate beyond the original

teaching module.

The model also contains elements of more general knowledge management; but

goes further for in knowledge management the technology can only present the

explicit knowledge, acting as a repository. This framework goes beyond this use of

technology in two ways.

Firstly, the reflection process is not left to the discretion of an individual, it forms

part of a taught module and so can be formally managed, offering a degree of

coercion not applicable to most other knowledge management processes.

Secondly, there is a tutor with expert knowledge explicitly to guide a student’s

reflection process. In most other knowledge management processes, dedicated outside

support is not available.

E-learning systems offer the tools to support this implementation and realise these

benefits. There are, however, non-technological issues to address.

4.1 Further Research

While the technology can enable the removal of learning outcomes from a module,

there are no current pedagogical, or matching administrative, models to support this

approach. The pedagogical implications of removing learning outcomes outside of the

originating module is the main area that needs to be addressed. There are implications

for assessment, such as the issue of re-examination should a student fail a module, if

it was possible that they could fail only one module that is, is particularly interesting.

The consequent question arises of which module, or modules, a student would need to

resit.

The overall validity to this concept of removing learning outcomes from a module

requires further refinement. Studies extending beyond the current scope of the

departmental study, including other universities are needed to establish the

applicability of this idea elsewhere. Also, this study considered only technical

undergraduates. Non-technical undergraduates, implicitly undergraduates already

motivated to learn transferable skills, may not benefit from this method of

encouraging their development of transferable skills in such a direct manner.

5 Conclusion

This study has shown that:

• Success in the use of e-learning relies on three factors: a student’s ability to use the

system, the development of material appropriate to the medium, and that these two

factors come together to engage the student. Thus e-learning can successfully be

used to deliver didactic knowledge to a student.

• E-learning can assist a student transform their knowledge into learning through

enabling opportunities to practice the skills, and providing opportunities for

reflection and feedback on those that practice. E-learning can thus encourage a

86

student to become move beyond being a passive recipient of knowledge and

become an active learner.

• E-learning can also enable the final stage in a student’s assimilation of transferable

skills: supporting them in applying the skills beyond the originating module. This

is of particular relevance to technical undergraduates who are documented as being

reluctant appliers of transferable knowledge. E-learning can maintain

communication between a student and their tutor, and a student and their taught

material, and so make it easier for them to apply their learning as transferable

learning.

This paper proposes a model to assist a tutor in understanding the requirements when

using an e-learning system to teach transferable skills needed for collaboration. There

remains the question of how far the assessment of learning outcomes outside the

originating module can be successfully accomplished, which remains an issue for

further research. However, it is only through the application of e-learning that we can

realistically ask the question at all.

References

1. Aczel, J., Fung, P., Bornat, R., Oliver, M., O’Shea, T. & Sufrin, B., 2004. Software that

assists learning within a complex abstract domain: the use of constraint and consequentiality

as learning mechanisms. British Journal of Educational Technology, 35(5), pp.625-638.

2. Colby, J., 2004. Attendance and Attainment, a comparative study. In Proceedings of the 5th

Annual Conference of the LTSN Centre for Information and Computer Sciences, 31 August

– 2 September, Belfast.

3. Conrad, D., 2004. University Instructors’ Reflections on their First Online Teaching

Experiences. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 8(2), pp.31-43.

4. Cox, S.A., Perkins, J. & Botar, K., 2004. Designing an E-Learning System that Supports Left

and Right Brain Dominance. In Proceedings of the 5th Annual Conference of the LTSN

Centre for Information and Computer Sciences, 31 August – 2 September, Belfast.

5. Dutton, J., 2002. How Do Online Students Differ From Lecture Students? Journal of

Asynchronous Learning Networks, 6(1), pp.1-20.

6. Fallows, S. & Steven, C., 2000. Building employability skills into the higher education

curriculum: a university-wide initiative. Education + Training, 42(2), pp.75-82.

7. Fayter, D., 1998. Issues in training lecturers to exploit the Internet as a teaching resource.

Education + Training, 40(8), pp.334-339.

8. Frith, V.F., Jaftha, J. & Prince, R., 2004. Evaluating the effectiveness of interactive computer

tutorials for an undergraduate mathematical literacy course. British Journal of Educational

Technology, 35(2), pp.159-171.

9. Furnell, S.M. & Karweni, T., 2001. Security Issues in Online Distance Learning.VINE,

31(2), pp.28-35.

10. Hammond, N. & Bennett, C., 2002. Discipline differences in role and use of ICT to support

group-based learning. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 18, pp.55-63.

11. Howard-Jones, P.A. & Martin, R.J., 2002. The effect of questioning on concept learning

within a hypertext system. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 18, pp.10-20.

12. Issroff, K. & Scanlon, E., 2002. Using technology in Higher Education: an Activity Theory

perspective. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 18, pp.77-83.

13. Kolb, D. A., (1984), Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and

Development, Prentice Hall, New York.

87

14. Landow, G.P., 1997. Hypertext 2.0. John Hopkins, London.

15. McKnight, C., Dillon, A. & Richardson, J., eds., 1993. Hypertext a psychological

perspective. Ellis Horwood, London.

16. Nabi, G.R., & Bagley, D., 1999. Graduate’s perceptions of transferable personal skills and

future career preparation in the UK. Education + Training, 41(4), pp.184-193.

17. Rainbow, S.W. & Sadler-Smith, E., 2003. Attitudes to computer-assisted learning amongst

business and management students. British Journal of Educational Technology, 35(5),

pp.615-624.

18. Salmon, G., 2002. E-tivities: the key to active online learning. Kogan Page, London

88