USING CRITICAL SUCCESS FACTORS FOR ASSESSING

CRITICAL ACTIVITIES IN ERP IMPLEMENTATION WITHIN

SMES

Paolo Faverio

CETIC,Università Carlo Cattaneo, Cso. Matteotti 22, Castellanza, Italy

Donatella Sciuto

Dipartimento di Elettronica e Informazione, Politecnico di Milano,Piazza Leonardo da Vinci 32, Italy – ITALY

Giacomo Buonanno

CETIC,Università Carlo Cattaneo, Cso. Matteotti 22, Castellanza, Italy

Keywords: ERP implementation, SMEs, Critical Success factors

Abstract: Aim of this research is the investigation and anal

ysis of the critical success factors (CSF) in the

implementation of ERP systems within SMEs. Papers in the ERP research field have focused on successes

and failures of implementing systems into large organizations. Within the highly differentiated set of

computer based systems available, the ERP systems represent the most common solution adopted by large

companies to pursue their strategies. On the contrary, until now small and medium enterprises (SMEs) have

shown little interest in ERP systems due to the lack of internal competence and resources that characterize

those companies. Nevertheless, now that ERP vendors’ offer shows a noteworthy adjustment to SMEs

organizational and business characteristics it seems of a certain interest to study and deeply analyze the

reasons that can inhibit or foster ERP adoption within SMEs. This approach cannot leave out of

consideration the analysis of the CSFs in ERP implementation: despite their wide outline in the most

qualified literature, very seldom these research efforts have been addressed to SMEs. This paper aims at

proposing a methodology to support the small medium entrepreneur in identifying the critical factors to be

monitored along the whole ERP adoption process.

1 INTRODUCTION

ERP systems are customizable, standard software

applications (Rosemann, 1999) that seek to integrate

the complete range of business processes and

functions to present an holistic view of the business

from a single information and IT architecture

(Gable, 1998). In spite of the benefits potentially

offered (Banker, et al., 1998, Davenport, 1998,

Gable, 1998), reports from the industry have pointed

out that ERP system implementations do not

guarantee the business benefits that they promised

(Wheatley, 2000).

The obstacles that limited benefit attainment

fro

m ERP implementation had seldom little to do

with lack of software functionality or major

technical issues, but were more often related to

people’s change and project management

competencies (Davenport, 2000, Mandal and

Gunasekaran, 2003).

The complex and pervasive nature of ERP

syste

ms makes the above-mentioned issues even

more relevant when small and medium enterprises

(SMEs) are taken into consideration since many

SMEs either do not have sufficient resources or are

not willing to commit a huge fraction of their

resources (Chan, 1999) due to the long

implementation times and high fees associated with

ERP implementation (Chau, 1995).

Organizational issues are also ofte

n claimed to

be one of the most important reasons for failures in

ERP system adoption (Davenport, 1993). Although

the organizational flexibility of SMEs should

theoretically favor ERP implementation, on the other

hand the low extent of formalization of people’s

285

Faverio P., Sciuto D. and Buonanno G. (2005).

USING CRITICAL SUCCESS FACTORS FOR ASSESSING CRITICAL ACTIVITIES IN ERP IMPLEMENTATION WITHIN SMES.

In Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, pages 285-292

DOI: 10.5220/0002547502850292

Copyright

c

SciTePress

roles and responsibilities makes the identification of

figures, such as the project manager and the key

users (Davenport, 2000), extremely difficult to

achieve.

Finally, the reinforcement of the concept of

business process is among the most critical success

factors in ERP implementation (Beretta, 2002).

Once again, SMEs seem in an unfavorable condition

since they generally suffer from a widespread lack

of culture as to the concept of business process

itself.

Whereas the overall research purpose is to

identify the Critical Success Factors (CSF) for ERP

implementation within SMEs and define metrics to

monitor them, this research work aims at identifying

the overall characteristics of SMEs in order to

explore their relationships with the CSFs in ERP

implementation.

This research project will address the following

questions:

RQ1 (step1): is it possible to identify and develop a

reference model to properly describe ERP adoption

cycle within SMEs?

RQ2 (step2): which are the SMEs’ characteristics

representing an obstacle to ERP adoption?

RQ3 (step3): which are the critical success factors

in ERP system implementation?

RQ4 (step4): in the light of the findings related with

step 2, which are the critical success factors in

project management within SMEs?

RQ5 (step5): is it possible to develop a

methodology able to identify the most critic

activities along the ERP adoption process?

In this paper the analysis of CSFs for SMEs will

focus on the area of project management only (a

complete analysis is available in the Center for

Economy and Technology of Information and

Communication (CETIC) internal report for 2004).

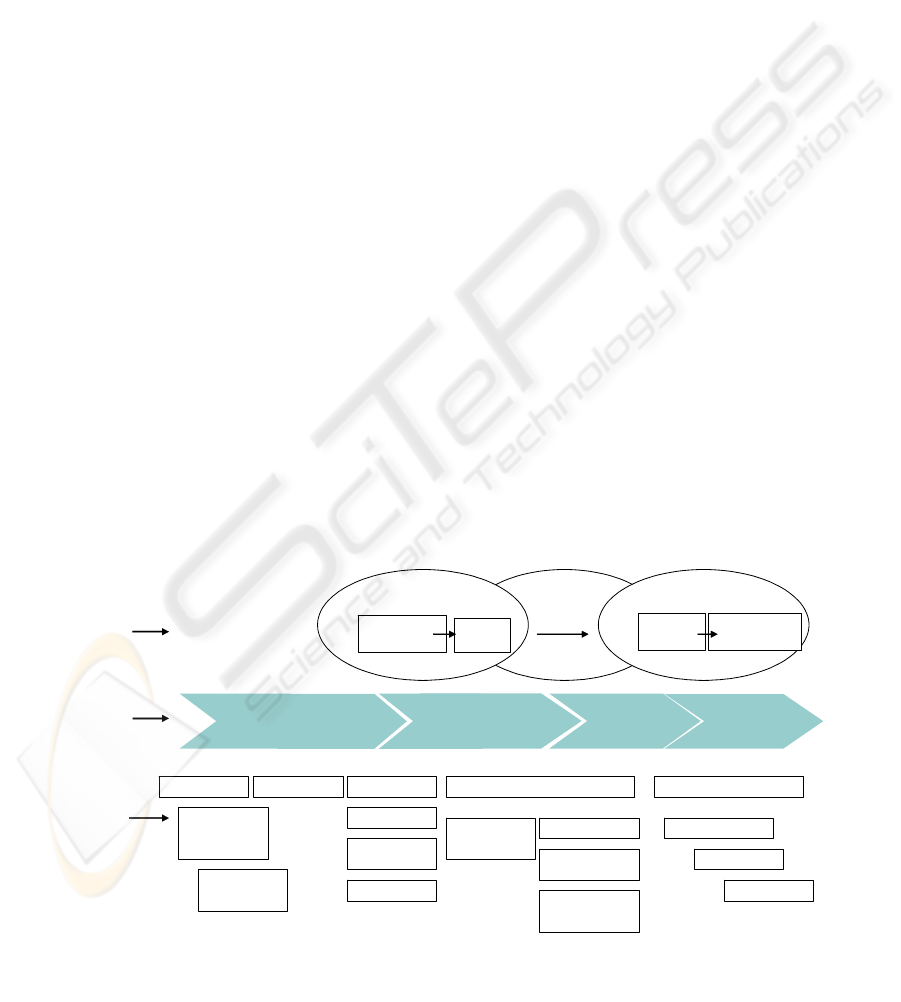

1.1 The reference model (RQ1)

The literature reports different approaches for

process development and improvement, in particular

Deming (1986) proposed the PDSA model (Plan-

Do-Study(Check)-Act), a four stage representation

strictly related to the concept of life-cycle. Its

universality allows representing also the different

stages typical of the IS management process. Soh

and Markus (1995) made use of such a concept of

“staged” life-cycle to explain the ability of

Information Technology (IT) in creating (or not to)

business value. Another similar, but more

circumstantiated perspective was added by Markus

and Tanis (2000) through the specification of a

chartering phase and also by a more precise

definition of both the domain and the purpose of

each stage.

The effectiveness of this approach lies in the fact

that its dynamism allows looking at implementation

as a sequence of stages and is then able to seek and

explain how outcomes develop over time (Boudreau

and Robey, 1999). Despite such a capability, the

scope of each stage in the Markus and Tanis model

still seems not sufficiently detailed when dealing

with SMEs. In fact, seeking an increased granularity

in detailing each stage could help improving both

the definition of the activities performed in each

stage and the appointment of people involved.

Therefore, the “Proven Path” methodology

IT

expenditure

IT

assets

IT

impacts

Organizational

performance

The “IT conversion” process

The “IT use” process The competitive process

IT management/conversion activities

Appropriate/

inappropriate use

Competitive position

competitive dynamics

Soh and Markus

(1995)

Markus and Tanis

(2000)

Reference model

based on the

“Proven path”

methodology in

Wallace and Kremzar

(2001)

Shakedown

phase

Onward /upward

Chartering

Project

p

hase

ASSESS/AUDIT

EXTERNAL

CONSULTANT

SELCTION

VENDOR &

SOFTWARE

SELECTION

VISION

COST/BENEFIT

ORGANIZE

PROJECT

SET GOALS

EDUCATE & COMMUNICATE

BUSINESS

PROCESS

DESIGN

MANAGE DATA

IMPROVE

PROCESSES

EDUCATE

SOFTWARE

CUSTOMIZATION

MEASURE

PILOT & CUTOVER

ASSESS

ONGOING EDUCATION

Figure 1: The reference model

ICEIS 2005 - DATABASES AND INFORMATION SYSTEMS INTEGRATION

286

(Wallace and Kremzar, 2001) was adopted with

some modifications, with the aim of subdividing

each stage in its specific sub-activities. A

software/vendor selection sub-activity has been

added as well as the choice of the external consultant

(

Figure 1).

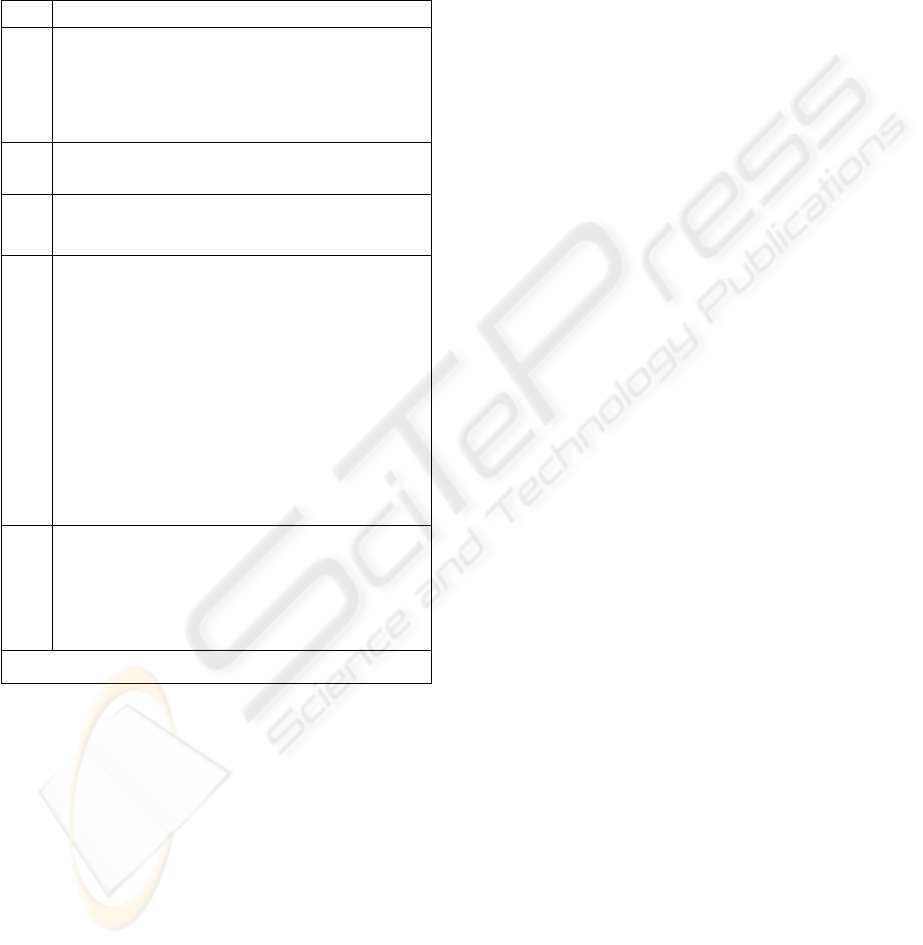

Table 1: Classification of SMEs characteristics being an

obstacle to ERP adoption

1.2 ERP adoption obstacles within

The capability of Enterprise Resource Planning

1.3 CSFs in ERP implementation

Despite the numerous benefits and promises of ERP

long the ERP adoption

2. etween the identified

3. or tactical role of CSFs in

To a iew on

CS

ain has been further

spe

Mandal and Gunasekaran, 2003) (

Table 2).

SMEs (RQ2)

(ERP) systems to efficiently and effectively manage

company’s resources by providing a total, integrated

solution for its information processing needs (Nah,

et al., 2001) has persuaded both practitioners and

managers of the importance of integrated systems,

not only for large multinational organizations but for

small and medium-sized firms too (Everdingen, et

al., 2000).Unlike large companies which often own

both the managerial competencies and adequate

financial resources, other studies (Raymond, 1992)

stressed out the weaknesses of SMEs in properly

managing the technology innovation. A previous

research by Gable and Stewart (1999) classified the

structural and managerial characteristics of SMEs

that hampers ERP adoption by the four specificities

they belong to. This classification was enriched with

a fifth specificity, the financial one, while a

literature review was performed to verify if other

factors could be relevant as to the original

taxonomy. 29 SMEs’ characteristics are reported in

Table 1 including the original factors identified by

Gable and Stewart.

Specificity Classification of SMEs characteristics being an obstacle to ERP adoption

Organizational

1. Low extent of formalization of people’s roles and responsibilities that is expressed by with their

continuous re-shuffle (Dutta and Evrard, 1999)**

2. The shift from a functional structure to a process-based view of the organization also requires the

verification of the alignment between both the IS and ICT architectures and the current

organizational structure (Luftman and Brier, 1999).**

3. It is often difficult to successfully implement a process-based approach, since it requires a lot of

time and money and results in a tremendous amount of change within the organization (Shields,

2001)**

4. SMEs are "resource poor" in human terms*

5. SMEs face a greater environmental uncertainty, as they have a lower measure of control over their

extraorganizational situation *

Decisional

6. The decision-making process of small business is less reliant on formal information and decision

models *

7. The strategic decision cycle or time frame of the SMEs is characterized as being: generally short

term, with a reactive rather than a proactive orientation; and less formal, using fewer formal

management techniques.*

Psycho-

Sociological

8. Owner-managers of SMEs are less prone to sharing information and delegating decision-making *

9. The decision-making process of small business managers is more intuitive and judgemental*

Information Systems

10. Limited resources in IS, including implementation and training (Levy and Powell, 2000) **

11. Need for skilled manpower involved in implementing and operating IS (Thong, 2001)**

12. SMEs underestimate the amount of time and effort required for IS implementation (Yap, 1989)**

13. lack of strategic planning of IS (Levy and Powell, 2000, Sweeny, 1999, Zinatelli, et al., 1996)**

14. Organizational information systems are generally under-utilized by SME managers.*

15. Within SMEs the non-development of adequate internal competencies limits the development of

real policies of IT specification and selection supporting the IS (Monsted, 1993; Schleich, et al.,

1990) **

16. SMEs are characterized by an underdevelopment of the IS with regard to the organizational

requirements (Cragg and Zinatelli, 1995; Lai, 1995; Lang, et al., 1997) **

17. IS planning within SMEs becomes more critical as technology becomes more central to SME

products and processes, and needs to be integrated with the business strategy (Blili and Raymond,

1993)**

18. The main objective for managers is to spend available financial resources on supporting

management systems that would improve day-to-day operations (Levy and Powell, 2000)**

19. Managers in SMEs tend to have less computer experience and training *

20. The information systems function in most SMEs is typically: in an early stage of evolution;

subordinated to the accounting function; lacking managerial expertise to plan, organize and

control the use of information resources of the firm; and possessing of a relatively low level of

technical systems development sophistication*

21. SMEs have limited expertise in IT (Levy and Powell, 2000)**

22. SMEs usually devote scarce resources to the IS department and, whenever they do, the IS staff

competence is strictly narrowed to technical issues (Palvia, et al., 1994, Soh, et al., 1994, Zinatelli,

et al., 1996)**

23. Lack of policies of IT specification and selection supporting the IS (Monsted, 1993; Schleich, et

al., 1990)**

Financial

24. The configuration and implementation of ERP systems still remain an expensive task for SMEs

(Mabert, et al., 2001)**

25. There are more barriers to IS implementation in small businesses than in large businesses due to

the high capital investment involved in implementing and operating IS (Thong, 2001)**

26. Small-medium entrepreneurs tend to choose the cheapest system which may be inadequate for

their purpose (Yap, 1989)**

27. Small- and medium-sized enterprises are not able to pay consultants millions of dollars for ERP

implementation (Scheer and Habermann, 2000)**

28. Significant lead times and high fees associated with ERP implementation (Chau and Patrick, 1995,

Hochberg, 1998)**

29. However, unlike large enterprises, small and medium-size enterprises (SME) cannot afford to

spend years on a software project (Al-Mudimigh, et al., 2001)**

** New factor identified

* Factor already present in Gable and Stewart’s classification (1999)

(RQ3)

adoption (Davenport, 1998, Gable, 1998), great

concerns have been expressed on the ability to

translate the potentials of an integrated information

system into a success story (Davenport, 1998). Even

though rather high levels of customization are

possible, enterprise systems push toward their

”logic” and the underneath best practice models.

Nevertheless, this may conflict with an

organization’s way of doing business and, as a

result, it can compromise or lead to the failure of the

ERP project. Hence, a considerable amount of

interest has been devoted to the identification of

critical success factors (CSFs) in ERP adoption

(Nah, et al., 2001, Somers and Nelson, 2004). These

studies used different approaches to classify the

most important CSFs in ERP implementation by

highlighting, alternatively:

1. their positioning a

cycle (Esteves and Pastor, 1999, Markus

and Tanis, 2000);

the relationships b

CSFs and specific dimensions of ERP

adoption (Motwani, et al., 2002, Umble, et

al., 2003)

the strategic

ERP adoption and implementation (Esteves

and Pastor, 2000, Stefanou, 2001).

ddress RQ3, a wide literature rev

Fs in ERP implementation has been performed.

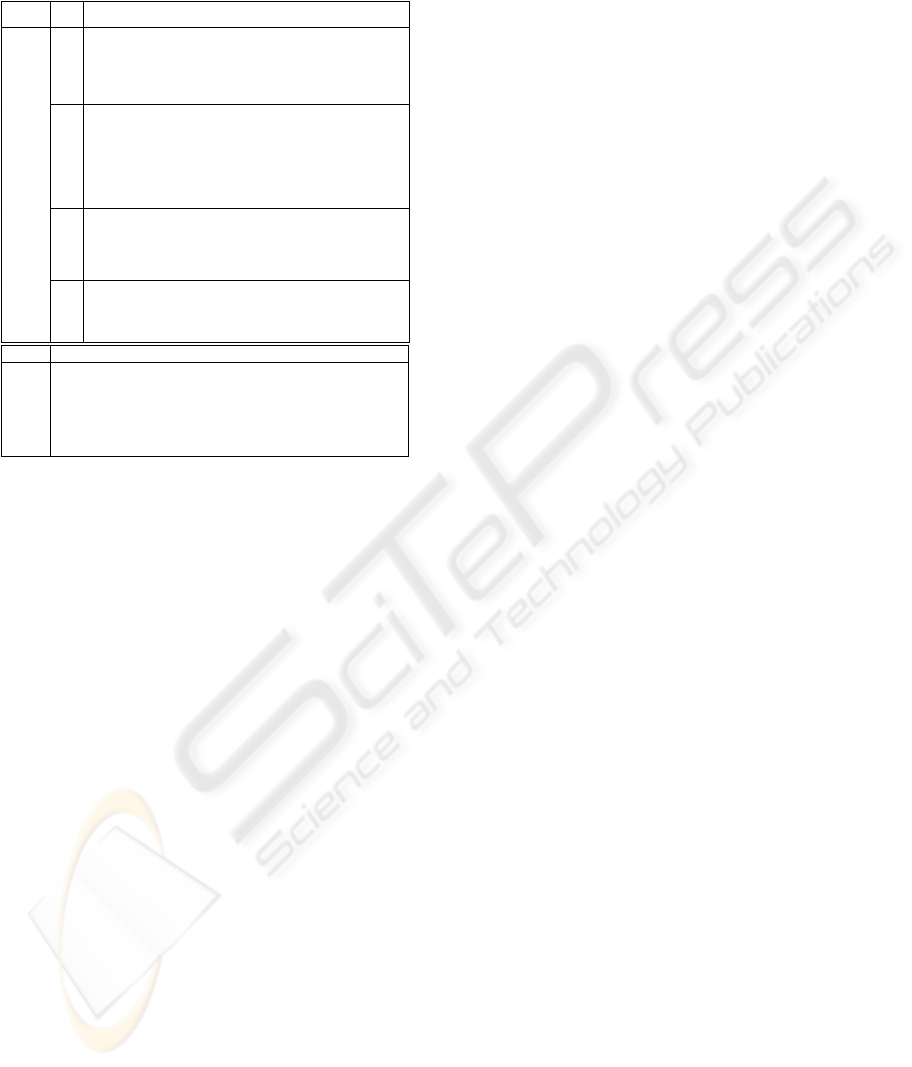

The 26 identified CSFs have been classified

according to a bi-dimensional scheme based on the

organizational and the technological domains

(Esteves and Pastor, 2000).

The organizational dom

cified by highlighting four typical dimensions of

ERP implementation such as process management,

project management, change management and

people’s dimension (Esteves and Pastor, 2001,

USING CRITICAL SUCCESS FACTORS FOR ASSESSING CRITICAL ACTIVITIES IN ERP IMPLEMENTATION

WITHIN SMES

287

Table 2: CSFs in ERP implementation

1.4 CSFs in project management

Although a number of research works have previously

cts of the

pro

quality.

needs and

expectations.

quirements (expectations).

1.4.1

R

personnel for the project team.

The t fluences

the implementation process (Esteves and Pastor,

s the

imp

since the financial

con

t plan or overall

schedule for the entire project

A pro due dates

among the project team members also guarantee the

(RQ4)

dealt with CSFs in ERP implementations using the

organizational and technological dimensions as

reading keys (Esteves and Pastor, 2000), so far none

of these studies has focused the analysis on SMEs.

The reference model showed in paragraph 1.1 allows

classifying the CSFs’ along the ERP life-cycle rather

than by simply grouping the identified CSFs as to the

dimension they belong to. The selection of CSFs in

the light of the characteristics of SMEs is only an

intermediate goal, since the final aim is to provide a

comprehensive framework and the related

methodological steps to support the evaluation of the

most critical issues in ERP implementation.

Project management deals with all aspe

ject, such as planning, organisation, information

system acquisition, personnel selection, and

management and monitoring of software

implementation (Al-Mudimigh, et al., 2001). The

project team’s business and technological competence

play a fundamental part in settling ERP

implementation success or failure (Somers and

Nelson, 2004) since the ERP projects may have to

contend with issues such as:

1. scope, time, cost, and

2. stakeholders with differing

3. identified requirements (needs) and

unidentified re

ecruitment, selection and training of

Dimension Area CSFs

process

management

• Need for establishing the process owner role (Davenport, 2000b)

• Reinforcement of the concept of business process (Beretta, 2002)

• Business Process Change (BPC) team (Beretta, 2002, Motwani, et al., 2002)

• Business Process Reengineering (Davenport, 1993, Hammer, 1999, Hammer and

Champy, 1993, Lucas, et al., 1988)

• Adequate IT infrastructure supporting knowledge sharing and communication

(Motwani, et al., 2002)

project

management

• Project evaluation measures (Umble et al., 2003)

• Project manager/leader profile and skills (Wallace and Kremzar, 2001; Willcocks and

Sykes,2000)

• Presence of super-users (Davenport, 2000b)

• Recruitment, selection and training of personnel for the project team (Mandal and

Gunasekaran, 2003)

• Clear definition of project objectives (Umble et al., 2003; Nelson and Somers, 2004)

• Steering committee’s tasks and responsibilities (Welti,1999; Nelson and Somers, 2004

• Initial ,detailed project plan or overall schedule for the entire project (Wallace and

Kremzar, 2001, Nelson and Somers, 2004)

change

management

• Presence of an executive-level project champion (Mandal and Gunasekaran, 2003)

• Commitment by top management (Esteves, et al., 2002, Somers and Nelson, 2004,

Umble, et al., 2003)

• Clear understanding of strategic goals (Mandal and Gunasekaran, 2003, Umble, et al.,

2003)

• Open communication and information sharing (Aladwani, 2001, Motwani, et al., 2002,

Somers and Nelson, 2004)

Organizational

People

dimension

• Extensive education and training (Umble et al., 2003)

• Cross functional training and personnel movement within the organization (Motwani,

et al., 2002)

• hands-on training (Aladwani, 2001)

• Commitment and motivation of users toward the innovation (Mandal and

Gunasekaran, 2003)

Dimension

CSFs

Technological

• Legacy systems knowledge (Esteves and Pastor, 2000, Themistocleous and Irani, 2001)

• Presence of internal IT capabilities/characteristics (Willcocks and Sykes, 2000; Mandal and

Gunasekaran, 2003)

• Adequate ERP implementation strategy (Davenport, 1998, Esteves and Pastor, 2000, Markus, et

al., 2000, Somers and Nelson, 2004, Umble, et al., 2003)

• Establish ERP selection and evaluation criteria (Esteves and Pastor, 2000, Somers and Nelson,

2004, Willcocks and Sykes, 2000; Verville and Halingten, 2003)

• Implementation consultants (Davenport, 2000; Somers and Nelson, 2004)

• Data accuracy/integrity (Umble et al., 2003; Somers and Nelson, 2004; K.M. Kapp, 1998)

s ructure of the project team deeply in

2000) since skills and knowledge of the project team

are critical in providing expertise in areas where team

members lack knowledge (Somers and Nelson, 2004).

Therefore project team composition demands multiple

skills covering functional, technical, and inter-

personal areas (Al-Mashari, et al., 2003) and top-

notch people who are chosen for their past

accomplishments, reputation, and flexibility (Umble,

et al., 2003). A multifunctional composition should

also count key users, people with bridge-building

interpersonal skills, together with in-house and in-

sourcing of IT specialists (Willcocks and Sykes,

2000) and third-party consultants (Welti, 1999).

Esteves and Pastor (2000) propose that also

consultants should be involved in a way that help

lementation process, in particular by sharing their

expertise and skills with the internal staff through an

adequate knowledge transfer mechanism (Al-Mashari,

et al., 2003). On the other hand, Welti (1999) warns

that even though the resort to external consultants

reduces the internal workload it also drains financial

resources from the company.

It’s very difficult to say which strategy fits better

with SMEs’ characteristics

straints and the available organizational skills are

inevitably context-dependent. Nevertheless, since

managers in SMEs tend to have less computer

experience and training (19), the resort to external

consultants seems not only advisable but even

mandatory. Finally, the limited resources, both human

and financial, devoted by SMEs to the IS department

and the scarce attitude of owner-managers in sharing

information and delegating decision-making (8) are

both reasons that suggest that this CSF must be

seriously kept in consideration.

1.4.2 Initial, detailed projec

per assignment of responsibilities and

availability of key users for those activities in which

they are involved (Wu, et al., 2002). Also unforeseen

changes in the people joining the team and in the

operating environment are both threats for an ERP

implementation. Wallace and Kremzar (2001) noticed

that since companies’ attention span is limited, as the

project priority drops, so the odds for success.

Overlooking this issue may be dangerous in particular

ICEIS 2005 - DATABASES AND INFORMATION SYSTEMS INTEGRATION

288

within SMEs, given that the amount of time and effort

required for IS implementation (12) is often already

underestimated and the decision cycle or time frame

is generally short term and with a reactive rather than

a proactive orientation (7). In conclusion, a proper

and timely project plan definition should be seen as a

preventive measure by owner-managers, since it

could prevent the project from suffering from extra-

organizational situation over which SMEs have a

lower measure of control (5).

1.4.3 Project manager’s profile and skills

ect

managers have to be experienced both in strategic and

pe of the project he’s

goi

In order to manage a project successfully, proj

tactical project management activities. In particular,

the project manager should be full-time, from within

the company and own an operational background

(Wallace and Kremzar, 2001).

The project leader should also have a track record

of success with the size and ty

ng to deal with (Willcocks and Sykes, 2000).

Furthermore, proven skills in managing both external

consultants and the inter-functional conflicts arising

from ERP implementation are required. Since an ERP

implementation should be business driven and

directed by business requirements, and not by the IT

department (Umble, et al., 2003), then internal IT

managers should be at least knowledgeable about how

the new technology could be affecting their business

(Willcocks and Sykes, 2000). The traditional structure

of an ERP project is quite complex since it demands

high coordination skills from several actors, such as

the project champion, the executive steering

committee and the project manager/team. But also

a different project configuration (entrepreneur, CIO

and the project team) which can realistically fit with

SMEs’ characteristics may cause an equal or maybe

higher degree of complexity since it overloads a

flatter and less responsive organizational structure.

This last structure compels the entrepreneur and the

CIO to carry out tasks that are often not compatible

with the time constraints typical of SMEs (Thong,

2001). That’s why some authors (Loh and Koh, 2004)

suggest that it should be advisable to hire an external

consultant having project management

responsibilities thus overcoming the organizational

overload and making up for any lack in project

management competences. Undoubtedly, the degree

of technical overspecialization of IS staff’s

competences (22) and the widespread lack of IS

strategic planning (13,17,20) are sufficient reasons for

small-medium entrepreneurs to carefully evaluate this

as a viable option.

1.4.4 Definition of project scope and

objectives

This critical success factor is related with concerns of

project goals clarification and their correspondence

with the organizational mission and the identified

strategic goals (Esteves and Pastor, 2000). Scope

specifies the degree to which the ERP system will

change managerial autonomy, task coordination, and

process integration in the business units of the

enterprise (Markus, et al., 2000) and implies the

definition by the highest authority of the project

organization, the steering committee, of the objectives

for the overall project (Welti, 1999). It implies the

definition of the scope of business processes and

business units involved, ERP functionality

implemented, technology to be

replaced/upgraded/integrated, and exchange of data

(Esteves and Pastor, 2000).

Timeliness of project should be managed

(Rosario, 2000) by creating aggressive but achievable

schedules (Umble, et al., 2003). This task requires a

detailed implementation schedule, better if created by

external consultants who are more experienced with

software and project scheduling (Welti, 1999). Since a

different scope in ERP projects requires different

levels of organizational authority and organizational

participation (Markus, et al., 2000), SMEs have also

to discount the need for more formal information and

decision models (6,7,9) with respect to the project

scope definition and objectives outlining activity.

Independently of the adopted implementation

approach (simultaneous, step by step, incremental),

owner-managers must also realize that sharing

information and delegating decision-making during

the definition of project scope and objectives is vital

(8), so that the centralization of decisions doesn’t turn

out to be a bottleneck during system implementation.

1.4.5 Project and system evaluation

measures

Although most project goals can be measured only

after project implementation because they ask for

results based on the implementation, or aim at

organizational changes, nevertheless all the actors

taking part in ERP implementation must share a clear

understanding of the goals (Umble, et al., 2003).

Specific and detailed performance targets for the

system are also required (Wallace and Kremzar,

2001).

On the other hand, project development must be

closely monitored too: consulting fees, replacing of

legacy systems and user training are some of the areas

evaluators should not ignore, while other authors

(Somers and Nelson, 2001) suggest the need for

USING CRITICAL SUCCESS FACTORS FOR ASSESSING CRITICAL ACTIVITIES IN ERP IMPLEMENTATION

WITHIN SMES

289

multiple management tools such as external and

internal integration devices and formal planning and

results-controls. This remark collides with the

relatively low level of sophistication of the decision-

making process within SMEs, being more intuitive

and judgmental, less formal and using fewer formal

management techniques (8,9). Then, SMEs should

consider the opportunity of adopting rapid

implementation tools (i.e. AcceleratedSAP) which are

commonly provided by consulting package vendors,

VARs and implementation partners (Chan, 1999).

SMEs could benefit of reinforced implementation

methodologies and also of the embedded project and

system performance evaluation measures.

1.4.6 Presence of key users

Key users’ tasks include determining how the system

will affect the procedures of the organization and

recommending system configuration and design detail

to the external contractor (Davenport, 2000, Wu, et

al., 2002). The criticality of such a role requires key

users to be chosen among the best performers in the

function or department they belong to (Davenport,

2000). Since SMEs are “resource poor” in human

resources (4), a first challenge is to free them up from

their daily routine by appointing new employees or

temporary staff (Wallace and Kremzar, 2001).

Anyway the replacement of key users with new/other

employees could be a minor issue within SMEs since

the availability of key users is de facto uncertain and

must be carefully evaluated by the entrepreneur. In

particular, the verification of the available skills

among the likely candidates could reveal the scarcity

of project and teamwork competences which are

typical of SMEs (15).

1.4.7 Steering committee’s tasks and

responsibilities

Previous researches outlined the importance of the of

Executive Steering Committee in ERP

implementation (Somers and Nelson, 2004) since it

should be the highest authority of the project

organization and must be responsible for setting the

objectives for the overall project by a precise

visioning and planning of implementation (Al-

Mashari, et al., 2003). Somers and Nelson (2004)

suggest that the Executive Steering Committee should

also be involved in system selection, monitoring

during implementation, and management of external

consultants. Other studies privilege the relevance for

the support by top management (Esteves and Pastor,

2000, Nah, et al., 2001) more than the deployment of

an official and dedicated board supporting and

leveraging ERP change and project management. The

short term and reactive more than proactive

orientation of strategic decision-making within SMEs

(7) should make the creation of a formal board

supporting implementation a favorable option, but it’s

also true that the organizational heterogeneity of

SMEs, in addition to other factors (12,13,18), suggest

this is possible and advisable just only when this pre-

requisite are met.

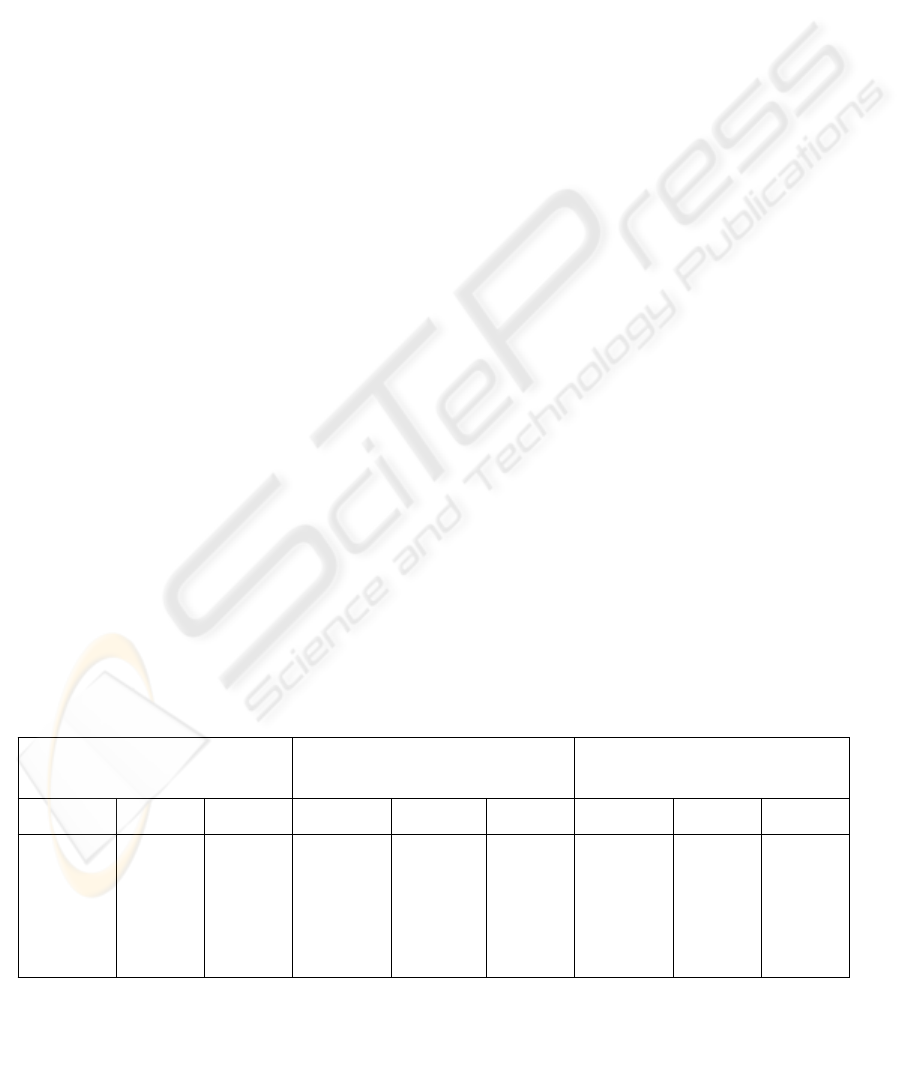

According to the characteristics of each CSF, it’s

possible to evaluate their criticality with regard to

different organizational and managerial

configurations of SMEs (Figure 2). In fact, the

achievement of the CSFs should be mandatory,

context-dependent or negligible depending on since

SMEs have remarkable differences as to the

organizational structure, internal competencies and

the human and financial resources available

(Buonanno, et al., 2005). In particular, mandatory

means that the company, owing the adequate

organizational and financial resources, should be able

to successfully implement the CSF. Finally, in the

case of a CSF labeled as context-dependent, SMEs

should theoretically deserve the maximum attention,

also acknowledging that the actions to be undertaken

need to be carefully evaluated in the light of the

resource and skills available. Finally, negligible is

related to the CSFs that rely on the participation of

actors from outside of the organization to be achieved

(i.e. an external consultant).

Medium-sized company with

adequate internal competencies and

a structured organizational profile

Medium-sized company with flat

organizational structure and no

relevant internal competencies

Small company

Mandatory Context

dependent

Negligible Mandatory Context

dependent

Negligible Mandatory Context

dependent

Negligible

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

2

3

4

1

5

6

7

2

4

5

1

3

6

7

Figure 2: Relevance of the identified CSFs as to the different organizational and managerial configurations of SMEs

ICEIS 2005 - DATABASES AND INFORMATION SYSTEMS INTEGRATION

290

1.5 Assessment of critical activities

along the ERP life-cycle (RQ5)

To evaluate possible critical activities along ERP

implementation, an “ex-ante/ex-post” approach has

been developed. The identified CSFs have been

placed along the reference model and, in particular,

along those sub-activities on which their effect is

supposed to disclose. The logic underneath this choice

is that often issues in ERP implementation are caused

just by the erroneous perceptions as to the relevance

of the CSFs themselves. Making use of a gap analysis

on ten-point Likert scale, the methodology aims at

highlighting inconsistencies between the “ex-ante”

and “ex-post” CSFs’ evaluation, thus revealing if no

adequate attention, human resources and money have

been deployed in performing the CSF-related

activities . The project leader has been identified as

the person in charge of the evaluation of the CSFs

since he is supposed to own the most visibility of the

ex-ante situation (e.g. the operational and strategic

choices on which the project is based on) as well as

the ex-post state of the project (i.e. the actual efforts

and activities made to successfully implement the

CSFs).

Two medium companies belonging to different

industries were requested to evaluate the relevance of

each CSF before implementation took place as well as

at the end of it.

Despite the differences related to the platform

adopted (SAP R/3 vs Oracle Business Suite) and the

business requirements, both business cases have

proven the methodology to be reliable in identifying

the inconsistent evaluation of CSFs’ relevance being

the cause of the issues, delays and bottlenecks

observed during the implementation process. The

detailed results of the model application are not

reported in the present work due to the limited space.

2 CONCLUSIONS AND FURTHER

RESEARCH

Despite the development of products with a range of

functionalities on a smaller scale as well as vertical

solutions to achieve a concrete reduction in

customization costs, there is not a general agreement

on the effectiveness of such systems within SMEs.

The methodology herein presented aims at making

ERP implementation a smoother process within

SMEs and its application in two business cases

proved the methodology to be very reliable in

identifying the reasons behind delays and bottlenecks.

This result also confirms that CSFs are not only a

slogan but a useful tool for preventing and

investigating critical issues in ERP implementation.

Further research will consist in other applications of

the methodology in order to verify and establish the

set of CSFs, their metrics and the related sources and,

moreover, to explore the possibility of highlighting

critical patterns in ERP implementations within

SMEs.

REFERENCES

Al-Mashari, M., A. Al-Mudimigh and M. Zairi, 2003.

Enterprise resource planning: A taxonomy of critical

factors, European Journal of Operational Research. 146,

352-364

Al-Mudimigh, A., M. Zairi and M. Al-Mashari, 2001. ERP

software implementation: an integrative framework,

European Journal of Information Systems. 10, 216-226

Banker, R. D., G. B. Davis and S. A. Slaughter, 1998.

Development Practices, Software Complexity, and

Software Maintenance Performance: A Field Study,

Management Science. 44(4), 433-450

Beretta, 2002. Unleashing the integration potential of ERP

systems: The Role of Process-Based Performance

Measurement Systems, Business Process Management

Journal. 8(3), 254-277

Boudreau, M.-C. and D. Robey, 1999. Organizational

Transition To Enterprise Resource Planning Systems:

Theoretical Choices For Process Research. In

International Conference on Information Systems

(ICIS).

Buonanno, G., P. Faverio, F. Pigni, A. Ravarini, D. Sciuto

and M. Tagliavini, 2005. Factors Affecting ERP Factors

Affecting ERP System Adoption: a Comparative

Analysis Between SMEs and Large Companies, Special

issue of Journal of Enteprise Information management,

(forthcoming).

Chan, R., 1999. Knowledge Management For Implementing

ERP in SMEs. In 3rd Annual SAP Asia Pacific. Institute

of Higher Learning Forum

Chau, P. Y. K., 1995. Factors used in the selection of

packaged software in small businesses: Views of

owners and managers, Information & Management.

29(2), 71-78

Davenport, T. H., 1993. Process Innovation: Reengineering

Work Through Information Technology, Harvard

Business School Press, Boston, MA

Davenport, T. H., 1998. Putting the Enterprise Into The

Enterprise System, Harvard Business Review. July/

August, 121-131

Davenport, T. H., 2000. Mission Critical: Realizing the

Promise of Enterprise Systems, Harvard Business

School Press, Boston, MA

Deming, W. E., 1986. Out of the Crisis, Massachusetts

Institute of Technology Center for Advanced

Engineering Study, Cambridge, MA

USING CRITICAL SUCCESS FACTORS FOR ASSESSING CRITICAL ACTIVITIES IN ERP IMPLEMENTATION

WITHIN SMES

291

Esteves, J. and J. Pastor, 1999. An ERP Life-cycle-based

Research Agenda. In First International workshop in

Enterprise Management and Resource Planning

(EMRPS'99). Venice,

Esteves, J. and J. Pastor, 2000. Towards the Unification of

critical Success Factors for ERP Implementations. In

BIT. Manchester,

Esteves, J. and J. Pastor, 2001. Enterprise Resource

Planning Systems Research: An Annotated

Bibliography, Communications of the AIS. 7(8), 1-52

Everdingen, Y. v., J. v. Hillegersberg and E. Waarts, 2000.

ERP Adoption by European Midsize Companies,

Communications of the ACM. 43(4), 27-31

Gable, G., 1998. Large Package Software: a Neglected

Technology?, Journal of Global Information

Management. 6(3), 3-4

Gable, G. and G. Stewart, 1999. SAP R/3 implementation

issues for small to medium enterprises. In Americas

Conference on Information Systems. Milkwaukee,

Wisconsin,

Loh, T. C. and S. C. L. Koh, 2004. Critical elements for a

successful enterprise resource planning implementation

in small- and medium-sized enterprises, International

Journal of Production Research. 42(17), 3433-3455

Mandal, P. and A. Gunasekaran, 2003. Issues in

implementing ERP: a case study, European Journal of

Operational Research. 146, 274-283

Markus, M. L. and C. Tanis, 2000. The Enterprise Systems

Experience-From Adoption to Success, R. W. Zmud,

Pinnaflex Educational Resources, Inc, Cincinnati, OH,

Markus, M. L., C. Tanis and P. C. v. Fenema, 2000.

Multisite ERP Implementations, Communications of the

ACM. 43(4), 42-46

Motwani, J., D. Mirchandani, M. Mandal and A.

Gunasekaran, 2002. Successful Implementation of ERP

Projects: Evidence from Two Case Studies,

International Journal of Production Economics.

75(Information Technology/Information Systems in

21st Century Manufacturing), pp. 83-96

Nah, F. F.-H., J. L.-S. Lau and J. Kuang, 2001. Critical

factors for successful implementation of enterprise

systems, Business Process Management Journal. 7(3),

285 -- 296

Raymond, L., 1992. Computerization as a factor in the

development of young entrepreneurs, International

Small Business Journal. 11(1), 34

Rosario, J. G., 2000. On the Leading Edge: Critical success

factors in ERP implementation projects, BusinessWorld

(Philippines). May 17

Rosemann, M., 1999. "ERP-software-characteristics and

consequences". In Proceeding of the 7th European

Conference on Information Systems. Copenhagen, DK.,

Soh, C. and M. Markus, 1995. How IT Creates Business

Value: A Process Theory Synthesis. In Proceedings of

the Sixteenth International Conference on Information

Systems,. Amsterdam, The Netherlands,

Somers, T. and K. Nelson, 2001. The Impact of Critical

Success Factors across the Stages of Enterprise

Resource Planning Implementations. In Hawaii

International Conference on Systems Sciences.

Somers, T. M. and K. M. Nelson, 2004. A taxonomy of

players and activities across the ERP project life cycle,

Information & Management. 41, 257-278

Stefanou, C. J., 2001. A framework for the ex-ante

evaluation of ERP software, European Journal of

Information Systems. 10, 204-215

Thong, J. Y. L., 2001. Resource constraints and information

systems implementation in Singaporean small

businesses, Omega. 29, 143-156

Umble, E. J., R. R. Haft and M. M. Umble, 2003. Enterprise

resource planning: Implementation procedures and

critical success factors, European Journal of Operational

Research. 146, 241–257

Wallace, T. F. and M. H. Kremzar, 2001. ERP: Making It

Happen, John Wiley & Sons,

Welti, N., 1999. Successful SAP R/3 Implementation:

Practical Management of ERP Projects, Addison-

Wesley Longman Limited, Reading, MA

Wheatley, M., 2000. ERP Training Stinks, Accessed on

(September/2004), available at

http://www.cio.com/archive/060100_erp.html

Willcocks, L. P. and R. Sykes, 2000. The Role of the CIO

and IT Function in ERP, Communications of the ACM.

43(4), 32-37

Wu, J.-H., Y.-M. Wang, M.-C. Chang-Chien and W.-C. Tai,

2002. An Examination of ERP User Satisfaction in

Taiwan. In Hawaii International Conference on System

Sciences.

ICEIS 2005 - DATABASES AND INFORMATION SYSTEMS INTEGRATION

292