INTERNET ADVERTISING AND THE HIERARCHY

OF EFFECTS

Regina P. Schlee

School of Business and Economics, Seattle Pacific University, 3307 Third Avenue West, Seattle, U.S.A.

Anthony Schlee III

Customer Insight Group, Avenue A/Razorfish, 821 Second Avenue, Suite 1800, Seattle, U.S.A.

Keywords: Internet advertising, hierarchy of effects.

Abstract: Internet advertising has been considered by many advertisers as a medium of direct response. Though this

classification was appropriate in the early years of internet advertising when consumers were expected to

click on 468x60 banners, current technology and high bandwidths now allow much greater creative

flexibility. Nevertheless, search engine advertising continues to take the largest share of online advertising

budgets. The challenge for internet advertising is to be able to take on additional roles in the hierarchy of

effects model of communications besides the call to action. This study examines data collected in two cases

that document the role of online display ads on consumer behavior. Online advertising can

take on a variety of roles: brand building, creating consumer interest, as well as calling for a direct

response. The results of this analysis are exploratory but point to the need of considering different forms of

internet advertising as serving a variety of functions in hierarchy of effects models of communications.

1 INTRODUCTION

2005 was a banner year for internet advertising. The

Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB) in cooperation

with PricewaterhouseCoopers estimates that internet

advertising revenues exceeded $12.5 billion in 2005

(IAB, 2006). This represents over a 30% increase

from the previous record of $9.6 billion in internet

advertising revenues in 2004. Almost three quarters

of U.S. consumers now have access to the internet,

and the proportion with broadband connections is

increasing at a rapid pace (Pew, 2006). According

to a March 2006 report by the Pew Internet &

American Life Project, within 4 years the proportion

of adult internet users with broadband connections

went from 10% to 37% (Horrigan, 2006). Internet

advertising has experienced a similar transformation.

According to Nielsen/ NetRatings AdRelevance,

traditional 468x60 banner ads have experienced a

decline of 50% from the first quarter of 2001 to the

fourth quarter of 2004, while leader boards (larger

banners that allow more creative flexibility) have

increased by 552% (Burke, 2005). However, in

spite of increased creative content, internet

advertising continues to be evaluated using some of

the standards that were developed ten years ago

when all online ads were viewed as a medium of

direct response and click through rates were seen the

primary indicator of effectiveness.

It is understandable why, as a new advertising

medium in the 1990s, internet advertising needed to

prove its effectiveness. Internet advertising agencies

prided themselves in providing more accountability

than traditional advertising, so click-through rates

(CTR) and conversions were seen as the most

appropriate indicators of effectiveness (Hollis,

2005). However, as the novelty of banner

advertising wore off, CTR declined (Drèze and

Hussherr, 2003). The decline in CTR was, in fact,

precipitous. In 1996, click through rates averaged

about 7%, but by 2002 CTR had dropped to about

0.7% (DoubleClick, 2003). As a result of a growing

disenchantment with internet advertising, online

advertising revenues declined in 2001 and 2002

(Hollis, 2005). Fortunately for internet content

providers and internet advertising agencies, this

decline was short lived. However, companies

222

P. Schlee R. and Schlee III A. (2006).

INTERNET ADVERTISING AND THE HIERARCHY OF EFFECTS.

In Proceedings of the International Conference on e-Business, pages 222-226

DOI: 10.5220/0001426402220226

Copyright

c

SciTePress

advertising on the internet continue to demand that

every dollar spent on advertising online brings the

anticipated result. This can be contrasted to

traditional offline advertising which often focuses on

brand building and is not expected to produce

immediate results. Students of advertising are

familiar with the famous John Wannamaker quote,

“I know I am wasting 50% of my marketing budget

… my trouble is that I don’t know which 50%.”

Internet advertising is expected to produce

immediate and measurable results and is still seen by

many as not being conducive to brand building.

This greater demand for accountability is best

demonstrated through the popularity of search

engine advertising. According to the Interactive

Advertising Bureau (IAB), search marketing

accounts for 40% of online advertising budgets,

compared to only 20% of online budgets spent for

display ads (Bruner, 2005). The popularity of

Google with advertisers reflects the desire to pay

only for demonstrated results. Advertisers

determine how much they want to pay when a

consumer clicks on a search keyword and bid

accordingly (Taylor, 2004). Of course, Google is

not the only player in search engine marketing as

Yahoo, AOL, and MSN have entered this lucrative

field (Acohido, 2003).

But, are the indicators of advertising

effectiveness that were developed for internet

advertising ten years ago still the most appropriate

measures of effectiveness, or can internet advertising

be viewed as providing some of the same influences

on consumer attitudes as traditional, offline

advertising? In other words, is all internet

advertising still a direct response medium, or can

different forms of internet advertising provide

different effects on the behavior of online

consumers? This study examines two case studies

that provide preliminary information on how online

advertising functions in the context of search

engines, as well as in the context of traditional

offline media. The first case analyzes the

contribution of online display ads for an advertiser

on consumers’ likelihood to use a search engine to

get additional information about the advertiser’s

service. The second case examines the contribution

of online display advertising in an environment

where consumers were also exposed to offline

media. Results from these two cases will be

interpreted using the hierarchy of effects model

examining the effect of different media on

consumers’ purchasing behavior.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Advertisers have long known that people generally

do not make spontaneous decisions when buying

products, but need to be taken through as series of

steps that have been called hierarchy of effects. The

logic of hierarchy of effects models is simple.

Consumers must first become aware of a product or

service before they buy. Then they have to get some

information about the product or service to develop

interest and a desire to buy. Barry (1987) reports

that the first complete model of hierarchy of effects

was developed by St. Elmo Lewis in the very early

years of the 20th century and contained four stages:

attention, interest, desire, action (AIDA). Barry

cites 38 elaborations of the original hierarchy of

effects model developed by Lewis, including the

widely cited DAGMAR model (Defining

Advertising Goals for Measured Advertising

Results) developed by Colley (1961) that aims to

measure the effects of advertising as consumers

move from awareness, to comprehension,

conviction, and action. Hierarchy of effects models

are discussed in almost all marketing and advertising

textbooks (Belch and Belch, 2006; Clow and Baack,

2004; Kotler and Keller, 2006). Nevertheless, there

is no discussion in those textbooks as to how internet

advertising fits within such models. And, given the

variety of internet advertising options available, do

all internet ads function in the same fashion, or do

they have different effects in the consumer’s

decision process?

Most advertising and marketing textbook also

discuss the concept of integrated marketing

communications (IMC). Integrated marketing

communications models work by having different

media working simultaneously on consumers to

produce the desired effect. For example, television

and magazine ads can create an interest in the

category, while sales promotions such as coupons

can create the call to action by giving consumers an

opportunity to “buy now.” Interestingly, at that time

when IMC models were first generated, consumer

search was conducted through telephone directories

such as the yellow pages which were viewed as

directional media, the kind of media one went to

after the decision to purchase a product had been

made. For marketers and advertisers in the early part

of the 21st century, there is little existing research on

how internet advertising complements other

advertising media.

It should be noted that hierarch of effects

models are not without their critics. Most criticisms

of hierarchy of effects models of advertising focus

INTERNET ADVERTISING AND THE HIERARCHY OF EFFECTS

223

on the possibility that consumers can take action

without going through a temporal sequence as

outlined in the AIDA and DAGMAR models

(Vakratsas and Ambler, 1999). A consumer’s

involvement level with the product category can, in

fact, influence how he or she processes advertising

information. There are situations where consumers

act with only a small amount of information about a

product or service and then develop attitudes about

their experiences. Behavioral influence and

experiential perspectives in consumer behavior

articulate different ways that consumers engage in

various actions and develop attitudes about the

products and services they have consumed

(Solomon, 2004). Critics of the model also claim

that the concept of integrated marketing

communications is antithetical to hierarchy of

effects models because all company communications

have to be directed to selling one idea (Weilbacher,

2001). However, hierarchy models do not imply

that the advertising be used to communicate a

different message at different stages, but rather than

the message be adapted to a consumer’s stage in the

decision making process. After the consumer has

obtained all the necessary information about the

product or service, it may be both unnecessary and

counterproductive to continue repeating the same

message in the same manner. Thus, realizing the

consumers use different modes of information at

different stages in the decision process helps

advertisers communicate more effectively and

efficiently.

3 RESEARCH FINDINGS

The object of this research is to examine how online

display ads can work together with other forms of

advertising to move consumer along the decision

process. Does display advertising providing

information about an advertiser’s product or service

result in a higher proportion of consumers who

request additional information through search

engines? In other words, does display advertising

lift the effectiveness of search engine marketing?

Our analysis of data in Case 1 seeks to answer this

question. Case 2 focuses on how display advertising

interacts with traditional offline media to facilitate

conversions (taking action) at the advertiser’s site.

Both sets of analysis seek to explore the manner in

which online display advertising acts as part of an

integrated marketing communications plan. Display

advertising can act both as an antecedent to

information gathering, as well as the call to action.

3.1 Case 1 – Effect of Display Media

on Search

One of the most difficult areas in advertising is the

ability to attribute buyer behavior on a specific form

of advertising. Earlier, we discussed the popularity

of search engine advertising through keywords. But,

how does a consumer get the idea to search for a

specific keyword? We can assume that consumers

decide to search for a specific product or service, or

for a specific company or brand because of another

stimulus. Hierarchy of effects models suggest that

another, earlier, stimulus created the awareness and

stimulated the desire for action. But, would display

advertising on the internet result in greater interest in

a specific company or brand? Our analysis of Case

1 seeks to examine how exposure to a retailer’s

display ad affected consumers’ usage of specific

search keywords. All data for this analysis were

provided by a global online advertising agency.

To test the effect of display ads on consumer’s

search behavior, we utilized an experimental design

whereby a segment of visitors to certain web sites

during 2005 were exposed to a display ad for an

online retailer (experimental/test group). Another

set of visitors where shown a public service ad at a

matched set of online websites. Cookie data allowed

us to track the behavior of internet users who were

exposed to the retailer’s ad and to compare their

search activities with the behavior of internet users

who were exposed to the public service ad (our

control group). Only individuals who allowed

cookies on their computer were included in our

experiment. Once an individual deleted or

“crunched” their cookies, he or she was taken out of

the study as we could no longer assign him or her to

the control or test (experimental) group. The data

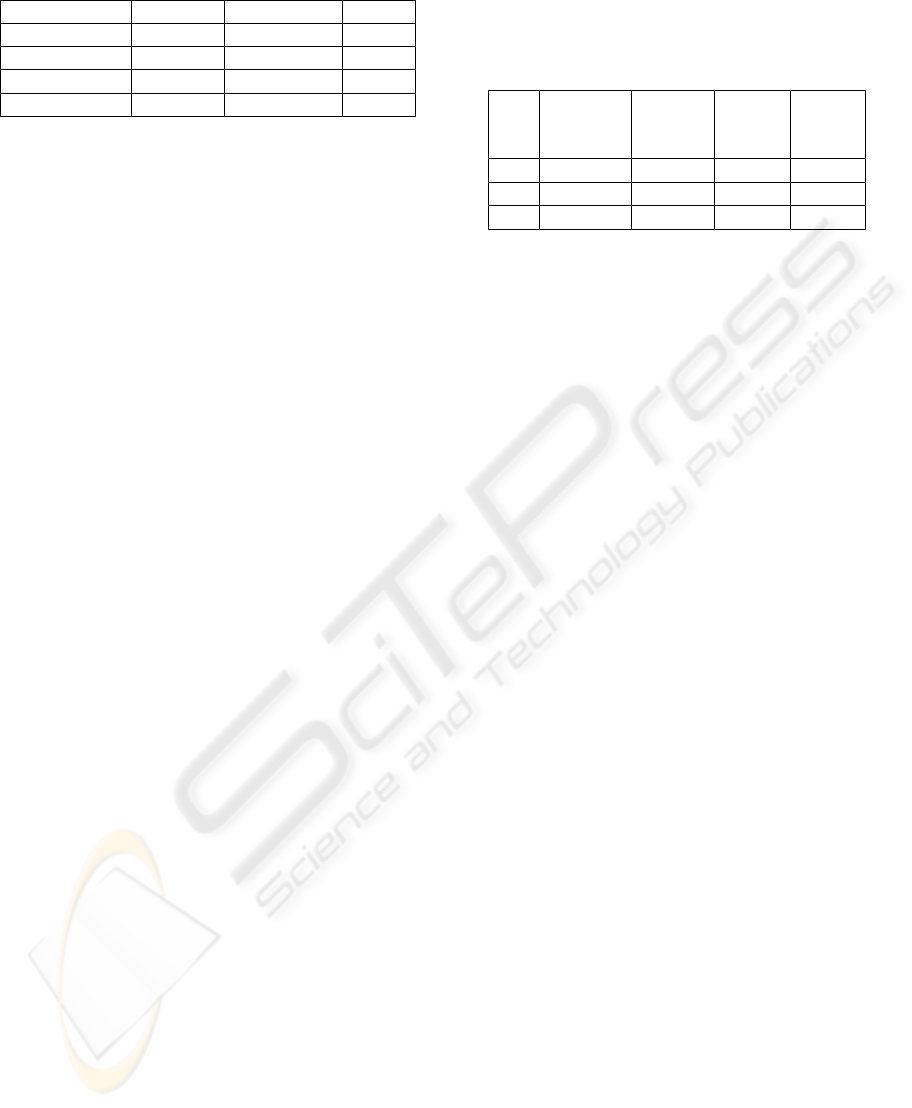

for this study are presented in Table 1.

In total, 12% of individuals who were exposed to

the web media followed up with a search to obtain

more information about this retailer’s product. This

compares to 10% of the individuals in the control

group who were not exposed to the online media.

Though the difference between 12% and 10% in

search activity may appear small, it represents a 23%

higher response for those exposed to web media.

This analysis demonstrates that it is possible to

measure the independent effect of display

advertising on consumer behavior. Furthermore, it

demonstrates that display advertising on the web had

a substantial added effect to all the other media used

by that advertiser and that it preceded in the

hierarchy of effects the use search engine

advertising.

ICE-B 2006 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON E-BUSINESS

224

Table 1: Effect of web media on search.

3.2 Case 2 – Effect of TV

Advertising and Display Media

on Conversions

Hierarchy of effects models assume that some

advertising generates awareness, while other types

of advertising generate interest and comprehension,

or a call for action. In situations where an advertiser

uses broadcast advertising to generate an emotional

response, can display ads on the internet increase

conversions at the client’s website through a call to

action?

To test the effectiveness of online media

compared to offline media (TV and radio), we

examined the effect of exposure to display ads under

three conditions: simultaneous exposure to offline

media in large metropolitan areas (primary DMAs),

smaller metropolitan areas (secondary DMAs), and

areas of the country where the client was not using

any offline media. The same methodology described

in Case 1 was used. A percentage of site visitors

were assigned to the experimental group and thus

were exposed to the advertiser’s display ad. The

control group was composed of visitors to the same

web sites who were shown a public interest ad. To

examine the effect of the online display ads on

consumer purchasing behavior, we tracked cookies

of those who were exposed to the display ad who

ordered the client’s product/service at the client’s

web site. The results of this research analysis are

presented in Table 2.

The findings of this study demonstrate a

substantial positive effect for online display media.

It should be noted that the effect of online media is

larger when combined with offline media. In

primary DMAs where the client used the heaviest

weight for offline media, the effect of online media

was largest. The online display media resulted in an

increase in conversions at the client’s website by

79.9%. In secondary markets where the weight of

the offline campaign was lower, the online display

media contributed to an increase in sales at the

client’s website by 48.1%. Where no offline media

were used, the lift for the online campaign compared

to the test group was 39.3%. These findings support

the integrated marketing communications model

discussed earlier whereby different elements of the

promotion mix are able to move consumers through

the hierarchy of effects leading to a sale.

Table 2: Effect of TV advertising and online display

media on conversions.

4 SUMMARY AND DISCUSSION

The two cases discussed in this study indicate that

online display ads can have a significant effect on

consumers’ online search and purchase activities.

They also indicate that display advertising online

can function differently than what is expected from a

simple direct response model. In Case 1, display ads

provided a substantial lift to the direct response

model of internet search marketing. The display ads

function in a manner consistent with the brand

building activities of providing interest and

comprehension in hierarchy of effects models of

consumer communications. In Case 2, the display

ads interacted with traditional offline advertising to

increase conversions at the retailer’s website.

Though the specific mechanism whereby

display ads affected consumers’ decision processes

has not been articulated yet, it is apparent that more

research needs to be conducted in this area. As the

penetration of broadband access to the internet

increases, so will the creative flexibility of internet

advertising. Future research needs to examine how

different forms of internet advertising can facilitate

the movement of consumers from the first stage of

the hierarchy of effects to the stage of placing an

order. Attention needs to be devoted to research that

measures the interactions between exposure to

different types of online media and offline media.

As advertisers become increasingly concerned with

the escalating cost and audience fragmentation of

offline media (especially TV advertising), internet

advertising will provide the means for maximizing

the effectiveness of integrated marketing

communications.

Saw web media Did not see web media Total

Search and no conversion 228,750 2,385,800 2,614,550

Search and converted 32,500 267,800 300,300

Total searches 261,250 2,653,600 2,914,850

Search conversion rate 12% 10% 10%

Primary DMA

Offline and online

Secondary DMA

Off line and

online

No Offline Ads Total

Test 14.9% 15.9 13.6 14.8

Control 8.3 10.8 9.7 9.1

Lift 79.9 48.1 39.3 61.6

INTERNET ADVERTISING AND THE HIERARCHY OF EFFECTS

225

REFERENCES

Acohido, B., 2003. AOL reels in search engine

Singingfish. USA Today, Nov. 11, 2003.

Barry, T. E., 1987. The development of the hierarchy of

effects: An historical perspective. Current Issues and

Research in Advertising, 10 (2): 251-295.

Belch, G. E., and M. A. Belch, 2006. Advertising and

Promotion: An Integrated Marketing Communications

Perspective, 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

Bruner, R. E., 2005. The Decade in Online Advertising,

1994-2004. DoubleClick, April 2005, accessed at:

http://www.doubleclick.com/us/knowledge_central/do

cuments/RESEARCH/dc_decaderinonline_0504.pdf

Clow, K.E. and D. Baack, 2004. Integrated Advertising,

Promotion, and Marketing Communications, 2nd ed.

New Jersey: Pearson/Prentice Hall.

Colley, R. H., 1961. Defining Advertising Goals for

Measured Advertising Results. New York:

Association of National Advertisers.

DoubleClick, 2003. DoubleClick 2002 Full-Year Ad

Serving Trends.

Drèze, X. and F.X. Hussherr, 2003. Internet advertising: Is

anybody watching? Journal of Interactive Marketing,

17 (4): 8-23.

Hollis, N., 2005. Ten years of learning on how online

advertising builds brands. Journal of Advertising

Research, 45 (2): 255-268.

Horrigan, J. B., 2006. For many home broadband users,

the internet is the primary news source. Pew Internet

& American Life Project (22 March 2006), accessed

at:

http://www.pewinternet.org/pdfs/PIP_News.and.Broad

band.pdf

Interactive Advertising Bureau, 2006. Internet advertising

revenues estimated to exceed $12.5 billion for full

year 2005. IAB Press Release (March 1, 2006),

http://www.iab.net/news/pr_2006_03_01.asp

Kotler, P., and K.L. Keller, 2006. Marketing

Management, 12th ed. New Jersey: Pearson/Prentice

Hall.

Pew Internet & American Life Project, 2006. 73% of

Americans go online. Accessed at

http://207.21.232.103/press_release.asp?r=127.

Solomon, M. R., 2004. Consumer Behavior, 6th ed. New

Jersey: Pearson/Prentice Hall.

Taylor, C. P., 2004. Engine of change. Adweek, March 15,

2005: 18-20.

Weilbacher, W. M., 2001. Point of view: Does advertising

cause a “hierarchy of effects?” Journal of Advertising

Research, 41 (6): 19-26.

ICE-B 2006 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON E-BUSINESS

226