AN INCLUSIVE APPROACH TO COOPERATIVE EVALUATION

OF WEB USER INTERFACES

Amanda Meincke Melo, M. Cecília C. Baranauskas

Institute of Computing, Unicamp, Caixa Postal 6176, Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil

Keywords: Accessibility, User Interface Evaluation, Cooperative Evaluation, Inclusive Design.

Abstract: Accessibility has been one of the major challenges for interface design of Web applications nowadays,

especially those involving e-government and e-learning. In this paper we present an inclusive and

participatory approach to the Cooperative Evaluation of user interfaces. It was carried out with an

interdisciplinary research group that aims to include students with disabilities in the university campus and

academic life. HCI specialists and non-specialists, with and without visual disabilities, participated as users

and observers during the evaluation of a Web site designed to be one of the communication channels

between the group and the University community. This paper shows the benefits and the challenges of

considering the differences among stakeholders in an inclusive and participatory approach, when designing

for accessibility within the Universal Design paradigm.

1 INTRODUCTION

Accessibility has been one of the major challenges

in user interface design for Web applications

nowadays. Besides enabling general access to

information needed for all citizens, it is a

requirement for the various domains such as e-

government and e-learning, in which knowledge and

education have been considered part of the mission

of nations and organisations.

Interface design for accessibility has long been

advocated as a fundamental requirement for

usability in general. Some efforts have also been

done towards the definition of recommendations for

providing the designers with tools to guide them in

designing and evaluating the applications

accessibility, especially Web sites.

Theories and methods in user interface design

have encouraged the participation of the user, in

different ways and through different phases of the

user interface production. The participation of users

in the interface design process has been considered

one of the best practices of the Human-Computer

Interaction (HCI) field. At the same time the

paradigm of Participatory Design (PD) has been

challenged when people with different types of

disabilities have been involved among the

participants of the design and evaluation process.

This paper brings this issue to discussion by

presenting a methodological proposal that extends

the Cooperative Evaluation Technique from PD with

artefacts of Organisational Semiotics (OS) to enable

an inclusive and participatory setting in a real

context of Web information system design. IPE is an

acronym for Inclusive Participatory Evaluation, a

new participatory technique we planned with the aim

of having people with different physical capabilities,

experiences and interaction styles participating

together in a cooperative evaluation of user

interface.

The IPE technique was applied successfully in

the context of “Todos Nós” project – an

interdisciplinary project being conducted in our

University, which aims at promoting educational

inclusion (Mantoan et al, 2005). Participants from

“Todos Nós” come from different professional

backgrounds, including people with disabilities. The

Web has been serving as an important

communication channel with people from inside and

outside our University, and Web-accessibility has

been one of the main concerns in the design of

“Todos Nós” portal.

Some results of using IPE are discussed in this

paper, especially considering the needs and benefits

of the technique in an inclusive environment to

evaluate accessibility and usability of Web user

interfaces. The paper is organised as follows:

Section 2 presents the theoretical background for

this work, which sets its basis on the concepts of

accessibility and the paradigm of Universal Design.

65

Meincke Melo A. and Cecília C. Baranauskas M. (2006).

AN INCLUSIVE APPROACH TO COOPERATIVE EVALUATION OF WEB USER INTERFACES.

In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems - HCI, pages 65-70

DOI: 10.5220/0002445500650070

Copyright

c

SciTePress

It is briefly presented here the two pillars of our

framework: Participatory Design and Organisational

Semiotics. Section 3 presents a summary of IPE

technique. Section 4 shows the first results of

applying it in a real context of user interface

evaluation. In Section 5 we conclude.

2 THEORETICAL

BACKGROUND

This work draws upon concepts and practices of

Participatory Design and Organisational Semiotics

to build a theoretical framework and understand

usability, accessibility and design for all as well.

In a broad sense, accessibility has been directly

related to the commitment of improving the quality

of life of elderly and people with disabilities (W3C,

2005; Bergman and Johnson, 1995). However,

taking into account the Universal Design philosophy

(Connell et al, 1997), it is possible to understand

accessibility as the easiness to approach and use

environments and products to the greatest extent

possible without discrimination. Although Universal

Design general principles point to ideal situations,

they constitute a valuable tool to guide the design

and the evaluation of more inclusive environments

and devices, which respect and consider the

differences among people.

Accessibility has been perceived as a necessary

attribute to the quality in use of software systems, or

to their usability (Bergman and Johnson, 1995;

Bevan, 1999; Graupp et al, 2003). If a user can’t

reach his/her objectives established in the interaction

with a computational system, the usability of this

system, relative to this user fails (Bergman and

Johnson, 1995; ISO, 1998). A design that

indiscriminately respects and considers the

differences among users must ensure that objectives

established in the interaction with a computational

system are reached (accessibility) with effectiveness,

efficiency and satisfaction (usability), to the greatest

extent possible (Graupp et al, 2003).

Besides Web-accessibility recommendations

(e.g. Section 508, Web Content Accessibility

Guidelines 1.0, and 2.0), in the Web context, there

are some techniques, which can be combined to

assess the accessibility of Web-based systems: the

use of different graphical and text-based Web

browsers, the use of assistive technologies,

automatic mark up languages validation,

accessibility verification with semi-automatic tools,

assessment based on checkpoints, evaluation with

users with different abilities and/or disabilities

(W3C, 2005; Graupp et al, 2003; Theofanos and

Redish, 2003). Nevertheless, there are still few

proposals in the literature considering the user’s

participation in an inclusive design setting.

Literature in Participatory Design has shown

different ways of including end-users in the process

of designing technology (Müller et al, 1997). PD

provides a set of techniques, which may support

different phases of the design lifecycle such as

problem identification and clarification,

requirements and analysis, high level design,

detailed design, evaluation, end-user customisation

and re-design.

In a PD perspective, a product is not only

designed for the users, but also with them,

collaboratively. In PD users’ engagement is

considered valuable to reach product quality, as it

allows a better understanding of their activities and

work context by the combination of different

experiences (Müller et al, 1997). At the same time,

PD can be useful to the users, inspiring them to think

about and analyse their own process of work. PD

could provide a valuable approach to inclusive

environments, where the individual differences must

be taken into consideration and users’ direct

involvement plays an essential role.

Particularly, the Cooperative Evaluation

Technique (Monk et al, 1993; Müller et al, 1997) is

a participatory practice to support the evaluation

phase, providing early feedback about re-designs in

a rapid iterative cycle. It can be used with an

existing product which will be improved or

extended, with an early partial prototype or

simulation, or with a full working prototype.

Designers without specialised knowledge of human

factors should be able to use it. Usually, an

evaluation team is formed of one end-user and one

developer to explore a software system or a

prototype, and develop criticism, so that changes

could be made to improve the product. In this work

we have adapted the Cooperative Evaluation

Technique with artefacts of Organisational

Semiotics to support participation of users with

different physical capabilities, experiences and

interaction styles in a cooperative and inclusive

evaluation of user interface.

Organisational Semiotics understands the

internal activities of an organisation, including its

information systems and its interactions with the

environment, as a semiotic system (Liu, 2000).

Organisation is understood in a broad sense,

meaning a group that shares some pattern of

behaviour and sign systems.

ICEIS 2006 - HUMAN-COMPUTER INTERACTION

66

We have been using some methods and tools

from OS to better understand the information system

behind the user interface in different levels (e.g.

physical, empirical, syntactic, semantic, pragmatic

and social). Particularly we have been using

methods from the set known as MEASUR in our

practice (Methods for Eliciting, Analysing and

Specifying User’s Requirements) (Liu, 2000) to

approach the design and the evaluation of technical

information systems, considering its social context

(e.g. responsible agents, behavioural patterns and

social norms).

Problem Articulation Method (PAM), for

example, is a method from MEASUR to be applied

in the initial phase of a project when problem

definitions are still vague and complex. Usually, it is

used to understand the aspects involved (e.g. needs,

intentions, existing conflicts, etc) in the design of an

information system, allowing a big picture of the

problem context, the main requirements and a shared

understanding among stakeholders (Liu, 2000). In

this work we adapted the Evaluation Frame – one of

PAM artefacts – to support the direct involvement of

users with disabilities in an inclusive participatory

evaluation of user interfaces.

3 IPE: INCLUSIVE

PARTICIPATORY

EVALUATION OF USER

INTERFACES

When designing with stakeholders from different

profiles (e.g. experiences, backgrounds,

capabilities), designers should be sensitive to

differences which come up and provide a flexible

setting to allow each stakeholder to participate

without discrimination.

Our first experience with IPE technique was

conducted with the participation of eleven members

of “Todos Nós” project. The participants have

different professional backgrounds and include

people with disabilities – one of them with low

vision and two with congenital blindness (both

Braille readers).

The technique was carried out to assess a

functional prototype of “Todos Nós” portal

(Mantoan et al, 2005). Its activities were planned to

take place during two to three hours. The aims of the

evaluation were to elicit accessibility and usability

problems, and to collect suggestions about the portal

interface design from prospective users.

During the exploration of “Todos Nós” portal, a

blind member, a low vision member and a sighted

member acted as users, while another blind member

acted as one of the observers. To guarantee the

participation of each member, some materials were

adapted to Braille (e.g. the participation term, the

task sheet, the observer's guide and the Evaluation

Frame) and/or printed with a larger font. Each

computer used during IPE activities had the

necessary technologies to support the interactions

between users and the portal (e.g. screen magnifiers

and screen readers). Although Perkins typewriters

were available for the blind participants, they

decided not to use them so their contributions could

be easily read by the other participants as well by

HCI specialists who would analyse them. Following

we summarise IPE technique.

3.1 Summary of the Technique

ABSTRACT – Three to four teams are composed by

one end-user and two observers (one of them could

be the system designer or an HCI specialist). Each

team criticises the software system user interface or

prototype. After that they share their impressions

about the users’ experience, supported by an

evaluation frame adapted from the Organisational

Semiotics artefacts.

O

BJECT MODEL AND MATERIAL – The software

system or prototype, a set of user’s tasks to help

focusing in the part of the user interface to be

evaluated, a set of questions – observer’s guide – to

help the observers to interact with the user,

recording materials (e.g. papers, pens and/or pencils,

audio and/or video records), a poster hanging on the

wall with the Evaluation Frame, and post-its to fill

the frame. Depending on the stakeholders’ physical

characteristics, it may be necessary to adapt some of

the materials and provide alternatives for note taking

activities.

P

ROCESS MODEL – Starting Talk: The co-

ordinator explains the activities to be carried out, the

roles to be played by each participant, and the need

for agreement concerning ethical values. Phase 1

(Concurrent Cooperative Evaluation): three to four

teams are formed so they assess the software system

or prototype concurrently; (a) each team, composed

of a user and two observers, criticises the software

system user interface or prototype supported by the

user’s tasks and the observer’s guide. While one of

the observers keeps a dialog with the user during the

tasks performance, the other takes notes about this

dialog and the user’s interaction with the interface

(e.g. the user’s hypothesis, his/her choices, bad and

AN INCLUSIVE APPROACH TO COOPERATIVE EVALUATION OF WEB USER INTERFACES

67

good impressions, commentaries about the software

system or prototype); (b) each team talks about the

activity carried out, summarising good and bad

characteristics of the software system user interface

or prototype, as well as the user’s impressions about

the interaction activity itself. Phase 2 (Write-Paste):

all the teams share their impressions about the

software system user interface or prototype,

discussing issues/problems and solutions/ideas

regarding the user’s experience, writing them down

on post-its, and pasting these post-its on the

Evaluation Frame.

R

ESULTS – Criticism of the prototype or software

system user interface, considering user’s experience,

especially as regards the accessibility; the register of

the problems found and some possible solutions,

taking into account the differences among

participants.

4 PRELIMINARY RESULTS

From the CONCURRENT COOPERATIVE

EVALUATION PHASE

we could perceive the users

had different strategies to browse, search and read

content in the portal.

In the execution of the first task regarding the

search for the Convention of Guatemala and its

interpretation, for example, the blind user, who

already knew the site structure by previous

experience on it, reached the “Law” section link

using TAB key and hearing screen reader feedback.

After entering in the “Law” section, she used the

screen reader search tool to look for the word

“decree” in the Web page. She perceived the second

occurrence of this word was part of the link to the

asked document, accessing it and completing the

task. This user spent about seven minutes to

complete the task, copying the answer from the Web

page and pasting it in a word processing document.

The low vision user, on the other hand, scanned

the navigation tree of the portal supported by the

mouse pointer and the screen magnifier – located at

the top of the screen, occupying a quarter of it. As

soon as this user found the “Law” section link, she

accessed it, selected the bold face presentation text

of the page with the mouse pointer and used the

Delta Talk software to help her reading the text. At

the same time she heard the selected text, she

scanned other parts of the Web page, but she didn’t

perceive there was a link to the asked document. So,

she decided to use de portal search engine to help

her in this task. The first attempt was unsuccessful,

as she entered an expression that referred to another

document. Entering a new keyword, she perceived

visual cues provided by the search engine, which

showed up the searched keyword in the page with

results, helping her to find the right link to the asked

document. After 35 minutes the execution of this

task was interrupted without conclusion.

The sighted user adopted an exploration strategy

to this same task. She accessed different sections of

the portal before entering the “Law” section. When

entering this section, she perceived the link to the

asked document, but understood it should be in the

“International Treats” subsection. This user spent

about seven minutes to complete the task,

summarising the answer in her task sheet.

The three users successfully completed the

second task, which asked for the definition of

“inclusion” in a published interview. The blind

initially tried to reach the interview through the

“Articles” subsection, without success. Thus, she

decided to take advantage of the portal search

engine, completing the task in five minutes. The low

vision user decided to make use of the portal search

engine at first, completing this task in seven

minutes. After exploring different sections, the

sighted user also decided to use of the portal search

engine, completing the task in nine minutes.

The blind and the sighted user also completed the

two extra-tasks, while the low vision user couldn’t

start them due to time constraints – IPE activities

should last no more than three hours. The first extra-

task asked for accessing a document in PDF format,

and the blind user reported some difficulties when

opening this kind of file through Web browsers as

some PDF files still have their content inaccessible.

The second extra-task, regarding the last published

news, was easily completed.

From the de-briefing – the talk established after

tasks execution – we emphasize the following

aspects:

• The best features of the portal: for the

sighted user it was the possibility of having a broad

view of what could be found in the portal; for the

low vision user it was the yellow cues provided by

the search engine showing up the searched word or

expression; while for the blind user it was the

absence of Flash presentations, the long descriptions

provided for the links and the possibility of

accessing all the provided links.

• The worst features of the portal: for the

sighted user it was the redundancy provided to the

main sections links (e.g. horizontal top menu and

vertical left navigation menu both providing access

to the main sections of the portal), and the use of the

same image to represent sections and subsections in

ICEIS 2006 - HUMAN-COMPUTER INTERACTION

68

the navigation structure; for the low vision user there

were nothing wrong with the portal; while for the

blind user it was also the redundancy considering the

main sections links: first the screen reader reads

aloud each section title and after it reads the long

description provided for each section link. For this

user each long description should be read together

with its link text. In fact, each link in the vertical left

navigation menu had a long description together

with its link text, but the screen reader didn’t give

her the chance to change between the link text and

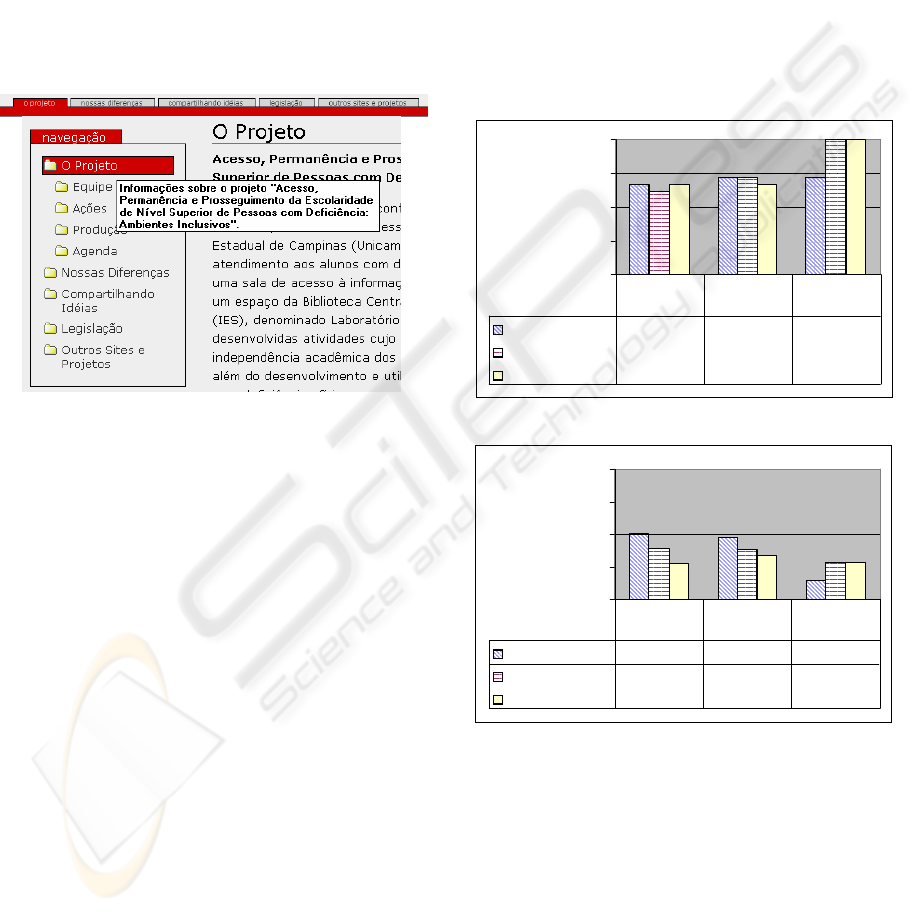

the long link description. Figure 1 illustrates the

horizontal top menu and vertical left navigation

menu.

• About the tasks: the three users reported the

asked tasks resemble activities they usually do in the

Web.

Analysing the Evaluation Frame data, from the

WRITE-PASTE PHASE, we identified some problems

without explicit solutions and vice-versa, suggesting

the existence of more problems and necessary

solutions than those explicitly pointed out by the

stakeholders. This is not surprising since stressing

all issues/problems and solutions/ideas weren’t the

only purpose of Write-Paste activity. This phase

aimed at allowing the group members to share their

experience with the portal, organizing and

registering their suggestions of improvement. The

following rates refer only to the issues/problems and

the solutions/ideas pointed out explicitly by the

group.

As it is illustrated in Figure 2, from 18

issues/problems related to interface design and

information design, 66,67% concern the blind user’s

experience, 61,11% concern the user with low

vision, and 66,67% the sighted user’s experience.

From the 21 reported solutions/ideas, 71,43%

concern the blind user, 71,43% concern the user

with low vision, and 66,67% concern sighted user.

Inspecting the Evaluation Frame we could perceive

many issues related to visual aesthetic (e.g. the need

for attractive visual elements, the need for better use

of blank spaces between groups of interface

elements), besides accessibility issues (e.g. the need

for better text description for the images, the benefits

of having access keys described together with their

link text, and the need for another colour schema to

cater for users with low vision). This could explain

the high percentage of issues/problems regarding the

sighted user besides the blind user. However, the

percentage of solutions/ideas related to the blind

user and the user with low vision is higher as a result

of the care to balance visual aesthetic proposals with

user interface accessibility.

If we consider only aspects related to

accessibility, we get a different picture from that on

Figure 2. As it is illustrated in Figure 3, the blind

user is the most affected by accessibility issues,

followed by the user with low vision. From 18

issues/problems 50% concern the blind user’s

experience, 38,89% concern the user with low

vision, and 27,78% the sighted user’s experience.

From the 21 reported solutions/ideas, 47,62%

concern the blind user, 38,10% concern the user

Figure 1: horizontal top menu and vertical left navigation

menu showing up the long description for its first link.

0,00%

25,00%

50,00%

75,00%

100,00%

Blind User

66,67% 71,43% 71,43%

Low Vision User

61,11% 71,43% 100,00%

Sighted User

66,67% 66,67% 100,00%

Issues/

Problems

Solutions/

Ideas

Functionality

Figure 2: Quantitative aspects from Evaluation Frame.

0,00%

25,00%

50,00%

75,00%

100,00%

Blind User

50,00% 47,62% 14,29%

Low Vision User

38,89% 38,10% 28,57%

Sighted User

27,78% 33,33% 28,57%

Is s ues /

Problems

Solutions

/Ideas

Functionality

Figure 3: Quantitative aspects from Evaluation Frame

regarding only accessibility problems.

AN INCLUSIVE APPROACH TO COOPERATIVE EVALUATION OF WEB USER INTERFACES

69

with low vision and 33,33% concern the sighted

user.

As there wasn’t a well-defined frontier between

issues/problems and solutions/ideas related to

functionality, we grouped them together in another

category. Among the seven suggestions regarding

functionality, only two of them are related to

accessibility: providing a form to send messages to

the portal team instead of only having the e-mail

contact published, and providing the users a way to

choose a different colour schema. The former would

benefit all users while the latter could improve the

interaction of sighted users and users with low

vision.

From this phase it is also registered that blind

participants want to have access to information

regarding visual aesthetic in images, but not only its

functional role. This wish was evident by the case of

the portal logo which functionally represents a link

to the portal main page.

5 DISCUSSION AND

CONCLUSION

This work has presented the Inclusive Participatory

Evaluation technique, which extends the

Cooperative Evaluation with the Evaluation Frame –

an artefact from OS. This technique supported the

assessment of a Web portal with prospective users in

an inclusive design setting.

Usually users from a Web application have

different backgrounds, experiences and capabilities.

The IPE technique was conceived to be applied in a

situation were users’ differences must be recognized

and considered in the design process.

The flexibility provided by the materials and the

behaviour of participants in the group dynamic

contributed to achieve results in which the solutions

were negotiated among people with different

capabilities and necessities in terms of user interface

interaction. This way IPE technique could allow a

designer to consider the real user’s experience (e.g.

technologies they use, the way the users deal with

their assistive technologies), and perceive the need

of balancing solutions that benefit their different

conditions.

While Concurrent Cooperative Evaluation

contributed to the exploration of a portal by different

users and observers showing them up some aspects

of interaction with the portal interface, the Write-

Paste activity helped them in organising and

registering their views and solutions, taking into

account the differences which exist among

themselves.

In summary IPE technique could support HCI

specialists and/or designer to assess technologies

with prospective users in inclusive design settings,

and effectively establish solutions committed to

different user’s needs. As a next step to this work,

we have been working on an Inclusive Web

Engineering Process that considers human factors

and users’ participation, in which this technique is

going to be integrated.

REFERENCES

Bergman, E., Johnson, E., 1995. Towards Accessible

Human-Computer Interaction. In: Nielsen, J. (ed.),

Advances in Human-Computer Interaction, Ablex

Publishing.

Bevan, N., 2001. Quality in use for all. In: Stephanidis, C.

(ed.), User Interfaces for All: Concepts, Methods, and

Tools, Lawrence Erlbaum.

Connell, B. R., Jones, M., Mace, R. et al, 1997. The

Principles of Universal Design, Version 2.0. Raleigh.

Retrieved April 2005, from The Center for Universal

Design, North Carolina State University:

http://www.design.ncsu.edu:8120/cud/

Graupp, H., Gladstone, K., Rundle, C., 2003.

Accessibility, Usability and Cognitive Considerations

in Evaluating Systems with Users who are Blind. In:

Stephanidis, C. (ed.), Universal Access in HCI:

Inclusive Design in Information Society, Vol. 4, Crete,

22-27, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 1280-1284.

ISO, 1998. ISO 9241-11 Ergonomic requirements for

office work with visual display terminals – Part 11,

Guide on usability.

Liu, K., 2000. Semiotics in Information Systems

Engineering, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge,

218p.

Mantoan, M. T. E., Baranauskas, M. C. C, Melo, A. M. et

al, (n.d). Todos Nós. Retrieved July 2005, from State

University of Campinas network:

http://www.todosnos.unicamp.br/

Monk, A., Wright P., Haber, J., and Davenport L., 1993.

Apendix 1 – Cooperative Evaluation: A run-time

guide. In: Improving your human-computer interface:

a practical technique, Prentice-Hall.

Müller, M. J., Haslwanter, J.H., Dayton, T., 1997.

Participatory Practices in the Software Lifecycle. In:

Helander, Martin G.; Landauer, Thomas K.; Prabhu,

Prasad V. (eds.), Handbook of Human-Computer

Interaction, 2nd edition, Elsevier, 255-297.

Theofanos, M., Redish, J., 2003. Bridging the gap:

between accessibility and usability. In: Interactions,

vol. 10, issue 6, New York, ACM Press pp. 38-51.

W3C, 2005. Web Accessibility Initiative. Retrieved April

2005, from World Wide Web Consortium Web site:

http://www.w3.org/WAI/

ICEIS 2006 - HUMAN-COMPUTER INTERACTION

70