INCREASING THE VALUE OF PROCESS MODELLING

John Krogstie

IDI, NTNU, Sem Sælandsvei 7-9 7030 Trondheim, Norway

Vibeke Dalberg, Siri Moe Jensen

DNV,Veritasveien 1, 1322 Høvik, Norway

Keywords: Business process modelling and re-engineering.

Abstract: This paper presents an approach to increase the value gained from enterprise modelling activities in an

organisation, both on a project and on an organisational level. The main objective of the approach is to

facilitate awareness of, communication about, and coordination of modelling initiatives between

stakeholders and within and across projects, over time. The first version of the approach as a normative

process model is presented and discussed in the context of case projects and activities, and we conclude that

although work remains both on sophistication of the approach and on validation of its general applicability

and value, our results so far show that it addresses recognised challenges in a useful way.

1 INTRODUCTION

Enterprises have a long history as functional

organisations. The introduction of machinery in the

18th century lead to the principle of work

specialisation and the division of labour, and on to

the need of capturing, structuring, storing and

distributing information and knowledge on both the

product and the work or business process. Business

process models have always provided a means to

structure the enormous amount of information

needed in many business processes (Hammer, 1990).

The availability of computers provided more

flexibility in information handling, and led to the

adoption of modelling languages originally

developed for systems modelling like IDEF0 (IDEF-

0, 1993). The modelling of work processes,

organisational structures and infrastructure as an

approach to organisational and software

development and documentation is becoming an

established practice in many companies. Process

modelling is not done for one specific objective

only, which partly explains the great diversity of

approaches found in literature and practice. Five

main categories for process modelling are proposed

based on Curtis, Kellner, and Over (1992), Totland

(1997), and Vernadat (1996):

1. Human-sense making and communication to

make sense of aspects of an enterprise and to

communicate with other people

2. Computer-assisted analysis to gain knowledge

about the enterprise through simulation or

deduction.

3. Business Process Management

4. Model deployment and activation to integrate

the model in an information system

5. Using the model as a context for a system

development project, without being directly

implemented (as it is in category 4).

In an ongoing project on model-based network

collaboration, we have investigated the practice and

experience of process modelling across four

business areas and a number of projects and

initiatives in a large, international company. Our

objective was to identify possible improvements and

facilitate potential sharing of relevant resources,

aiming towards an optimisation of value gained from

modelling and models. Merriam-Webster Online

defines value as: “something (as a principle or

quality) intrinsically valuable or desirable”. We have

aimed for a company-wide, inclusive scope in our

use of the term value, guided by what has been

deemed relevant by involved stakeholders.

Three important observations were made during

the early stages of the project:

70

Krogstie J., Dalberg V. and Moe Jensen S. (2006).

INCREASING THE VALUE OF PROCESS MODELLING.

In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems - ISAS, pages 70-77

DOI: 10.5220/0002457800700077

Copyright

c

SciTePress

• Even within projects a variety of objectives was

found, spanning the categories presented above. A

corresponding variety was found in tools, methods

and attitudes to the potential value of modelling.

• In some initiatives there were significant

divergence of expectations to the modelling results

and value - between different stakeholders and also

over time.

• Communication and sharing of resources

between projects were mainly done through more or

less ad-hoc reuse of models and personnel

personally known by project workers in advance.

From this we made three assumptions:

• Single project value and stakeholder

satisfaction could be increased by to a larger degree

focusing on, communicating and prioritizing

between diverging expectations and objectives.

• This would require a common platform for

communication about modelling initiatives

expectations, objectives, and other attributes.

• Such a platform could also facilitate reuse of

relevant knowledge, tools, models, methods and

processes between units and projects.

These assumptions lead to the development of a first

version of a framework proposal on best practice for

increasing the value of process modelling and

models. This proposal consists of a taxonomy, a

recommended model of activities for process

modelling value increasing initiatives, and links to

relevant knowledge and best practices for each step

of the process. Work leading up to this work has

been reported in (Dalberg et al, 2003; Dalberg et al

2005; Krogstie et al, 2004; Krogstie et al, 2005).

The rest of this paper presents the methods used

in our work, from identification of needs,

development and assessment. We then give an

overview of our first version of the framework of

best practice for increasing the value of process

modelling and models, and discuss its applicability

with regard to challenges identified in earlier

projects. Finally, we conclude on the applicability

and usefulness within the limitations of our

validation, and indicate needs for further

development of the framework as well as for more

large-scale validation within a wider scope.

2 RESEARCH METHODS

The research presented in this paper is based on

qualitative analysis of a limited number of case

studies. According to Benbasat, Goldstein, and

Mead (1987), a case study is an approach well suited

when the context of investigation takes place over

time, is a complex process involving multiple actors,

and is influenced by events that happen

unexpectedly. Our situation satisfies these criteria,

and the work has taken place within the frames of a

three year project, including one in-depth case study,

and several other less extensive studies. In deciding

whether to use case studies or not, Yin (1994) states

that a single case study is relevant when the goal is

to identify new and previously not researched issues.

When the intent is to build and test a theory, a

multiple case study should be designed. The

intention of our study has been to find out how to

increase the value of modelling and models in an

organisation. There has not been reported much

research within this area earlier, and we have

therefore chosen a multiple case approach for the

work presented in this paper, in order to investigate

this research area closer.

The framework for increasing value of process

modelling and models presented in this paper has

been developed through an iterative process, refining

the model. So far we have been through four

iterations.

In the first iteration we studied the modelling

initiative in a particular project in detail, using

observation, participation, and semi-structured

interviews. After initial explorative research, we

focused on identifying the expectations and

experiences towards the modelling and the models,

on their score related to process modelling success

factors, as well the extensive reuse of the models

across the organisation, viewing this as possible

knowledge creation and sharing as a part of

organisational learning. An initial hypothesis on

process modelling value was established, based on

our findings regarding the importance of the relation

to the context of modelling versus the context of use.

In the second iteration, we went through semi-

structured interviews with representatives of several

different modelling initiatives throughout the

organisation to survey their experience with

modelling, especially with respect to benefits and

value of reusing knowledge through models across

projects and organisation. A number of initiatives

were selected for the study where we were able to

get in-depth knowledge from those involved in the

process. An interview guide for interviews with key

stakeholders was established. These interviews were

focused on expected and experienced use and value

from the modelling efforts in the case study, aiming

at identifying as many expectations as possible,

including any that may not have been documented in

project documentation, because they were not

considered directly relevant for the project goal.

After initial open questions, the interviews were

structured around keywords from the work of

Sedera, Rosemann, and Doebli (2003) concerning

INCREASING THE VALUE OF PROCESS MODELLING

71

“process modelling success”. Documentation of the

study is based on these interviews, studies of project

documentation and models. The information from

the interviews was partly structured through the use

of the interview guides. The guides were used as

basis for structuring contact summary sheets with

the main concepts, themes, issues and questions

relating to the contact (Miles and Huberman, 1994).

As a third iteration we carried out a workshop

with a group of modelling experts, discussing the

framework in relation to their own experiences

through numerous process modelling projects. This

resulted in an updated version of the framework.

In what has so far been our last iteration, we

included the framework in an actual business project

using action research, where one of our researchers

also acted as a modeller. This was an informal test of

the framework, but gave valuable input to updating

it. We also saw the value of the framework in a

modelling initiative through this test, where it gave

positive guidance for the modelling. The next

iteration of the development of the best practice

framework should be to conduct more formal tests.

Our results and approach this far has certain

limitations relative to internal validity (Miles and

Huberman, 1994), as representatives of some of the

involved roles have been followed more closely than

others. As for descriptive validity (what happened in

specific situations) the close day to day interaction

with the users, especially in the first and the last

iteration by one of the researchers, give us

confidence in the results on this point. As for the

interpretive validity (what it means to the people

involved) we have again in-depth accounts from

central people in main roles, but again not all the

involved roles have been represented to the same

degree. The same can be said on evaluative validity

(judgements of the worth and value of actions and

meaning). That we find many results that fit the

categories of existing theoretical frameworks gives

us confidence on the theoretical validity of the

results.

3 A FRAMEWORK FOR

INCREASING THE VALUE OF

PROCESS MODELLING

This best practice framework aims to increase the

value of the modelling and models through enhanced

awareness about current and future stakeholders, any

(potential) conflicts of interest, stakeholder

expectations and potential value to be gained, as

well as any negative effects increasing total cost.

Based on this knowledge, decisions regarding

resource allocation, modelling methods and tools,

responsibilities etc can be made to optimize the

value of a modelling activity and its resulting

models, on a project level as well as on an

organisational level. The basic elements of the

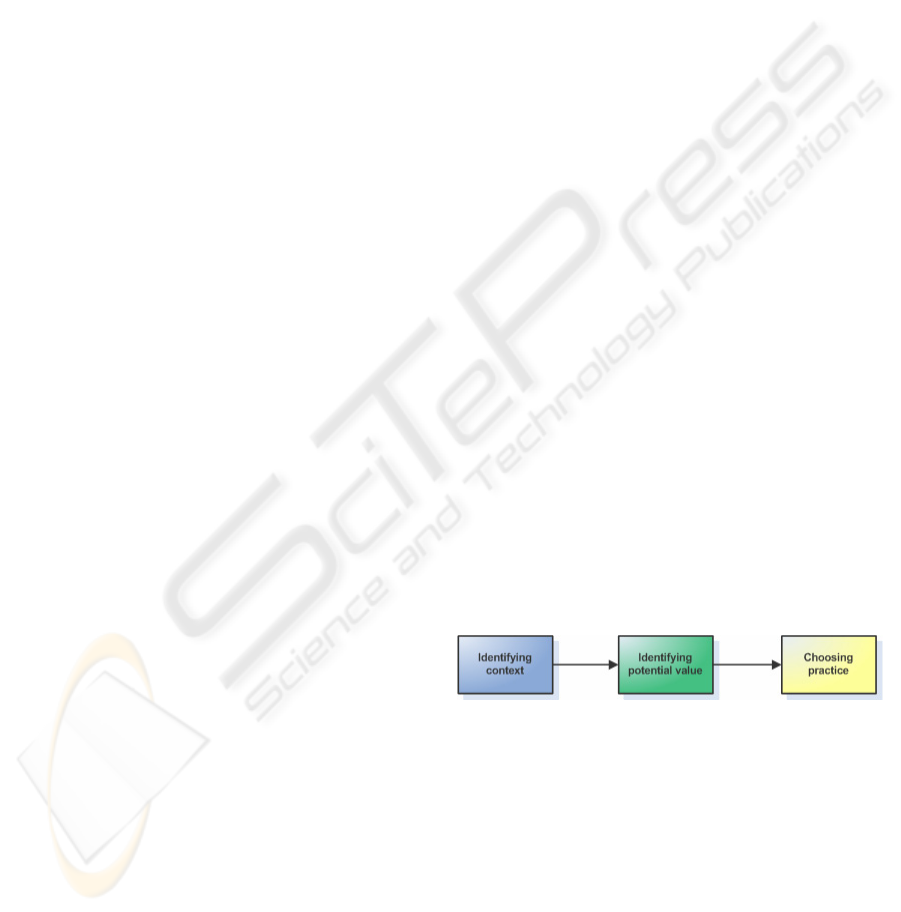

framework are a recommended main process (see

Figure 1) and some basic concepts, elaborated on in

the description of each step in the main process.

Context is the surroundings of an initiative that

might influence decisions. Value is identified in

relation to the identified context, but also on

potential value outside the initial project scope. The

practice focuses on the strategies and practice

around the modelling and the models.

The recommended process is initiated when a

need for modelling has been identified. Its three

main steps are detailed below.

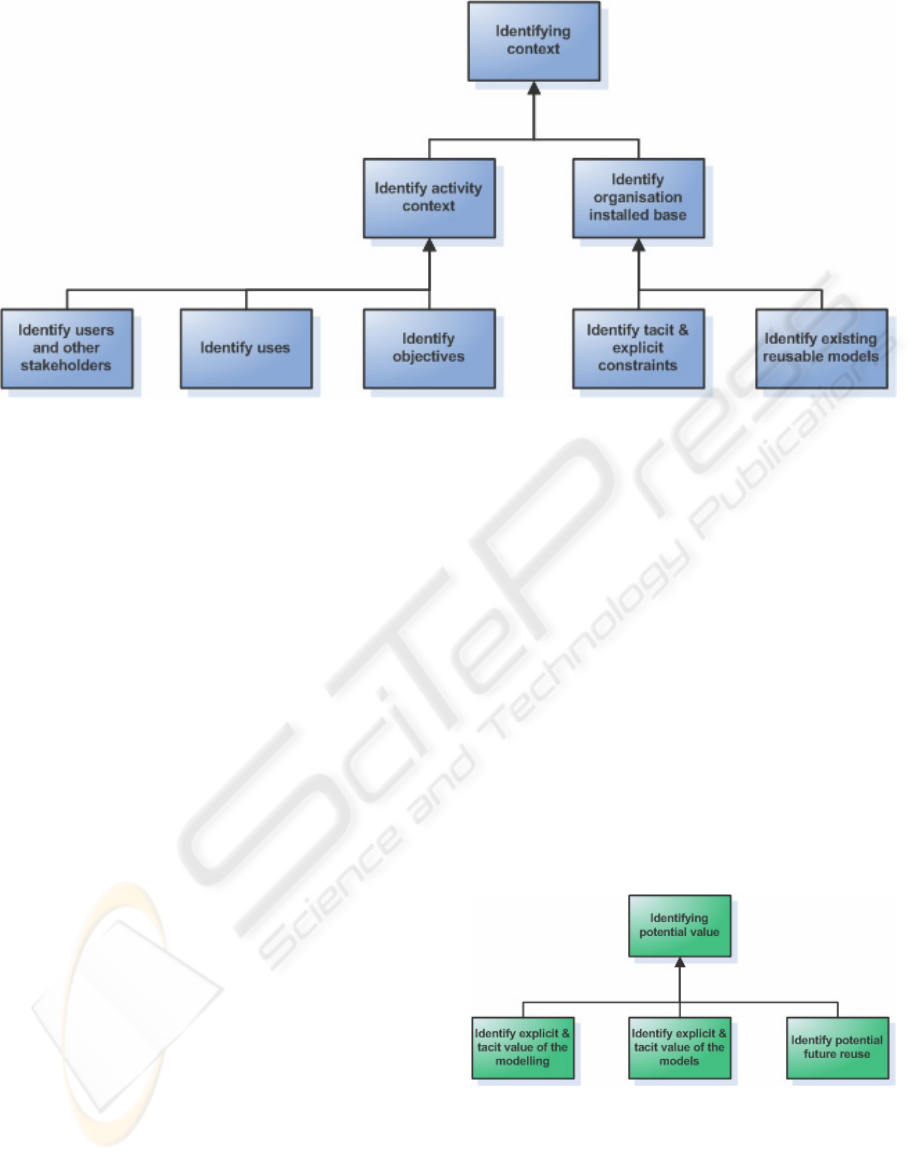

3.1 Identifying Context

Identifying the context is mostly about expressing

the circumstances of the identified need for

modelling, as a basis for further communication,

prioritization and planning. It will usually coincide

with the writing of an application for funding,

development of a project mandate and/or a project

plan. At this step one should keep within the scope

of the initial need, usually expressed in traditional

project documentation with formal obligations. The

main issues to be clarified are detailed in Figure 2,

and include:

• Identification of the context of the modelling or

model activity/initiative, including users and

other stakeholders, uses, and objectives.

• Identification of the organisations installed

base, including existing reusable models or

descriptions and other relevant tacit or explicit

constraints.

Figure 1: The overall framework.

ICEIS 2006 - INFORMATION SYSTEMS ANALYSIS AND SPECIFICATION

72

Figure 2: Identifying context.

There are different actors related to a modelling

initiative and a model, holding one or more roles.

Users are using the models or participating

personally in the modelling in order to achieve

objectives. Other stakeholders may not be using the

models directly, but extract value from planned

objectives. Techniques e.g. from user-centred design

is useful at this stage in the identification of

stakeholder types. Use includes how the modelling

and models are going to be used in order to achieve

the objectives. Objectives are the goals and purposes

of the modelling and models. Installed base includes

tacit and explicit assets already existing in the

organisation that will have influence on the

modelling and model context. Constraints include

issues such as personal and organisational

knowledge, which may be tacit or explicitly

expressed constraints, organisational guidelines or

instructions (explicit constraints), existing tools and

languages etc. Reusable models are models or other

documentation that were created for other purposes,

but that could be reused in the new project.

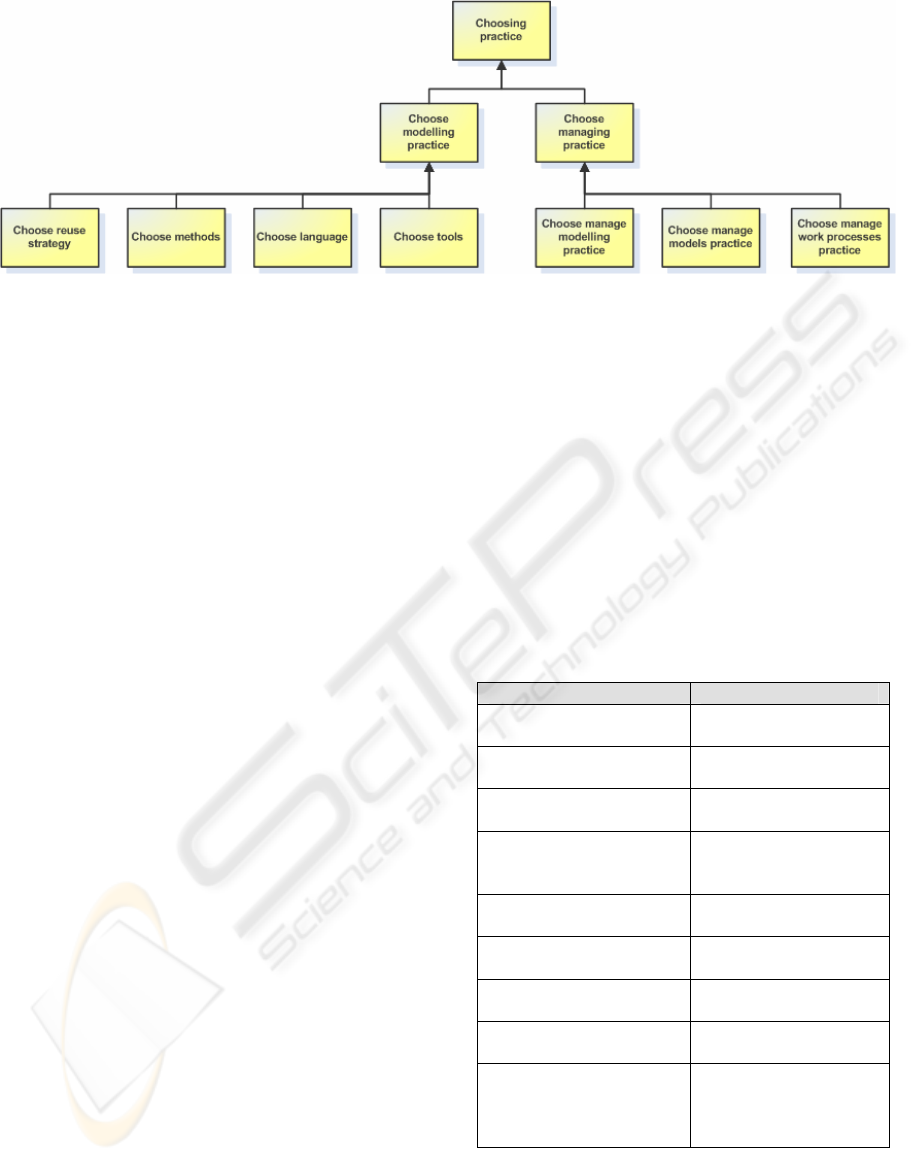

3.2 Identifying Potential Value

In step 1, we identified the context where the

modelling and the models were meant to play a role.

In step 2, “Identify potential value”, the aim is to

capture any (potential) extra and positive benefits of

the modelling and models, exceeding the primary

objectives captured in step 1. Value may be

connected to the resulting models, or to the

modelling activity in itself.

Often the objectives identified in step 1 will

relate to the modelling or model initiative, while any

potential value to the rest of the organisation will

typically be ignored in the formal project

documentation developed at this stage – due to a

lack of awareness, or to avoid complicating

responsibilities and bindings.

Value can be explicit and easy to grasp, but also

tacit. Tacit value, e.g. the improved understanding of

a work process for a modeller originally producing

models for others, are often not explicitly captured

in traditional project documentation, but may still

affect decisions before or during a project, or the

perceived value of the project in retrospect. Future

reuse of the models can be an added value of the

current modelling and models, especially if this

potential is taken into account at an early stage.

Figure 3: Identifying potential value.

INCREASING THE VALUE OF PROCESS MODELLING

73

Figure 4: Choosing practice.

3.3 Choosing Practice

The choice of a suitable practice should be based on

the identified contexts of the modelling and models,

as well as the identified expected value. Modelling

practice include reuse strategy, methods, languages

and tools, while managing practice define how to

manage the modelling, the models and the work

processes. The general framework of quality of

models and modelling languages inspired by

organizational semiotics (Krogstie and Sølvberg,

2003) is especially helpful here relative to modelling

practice related to methods, languages, and tools,

having the stakeholders of the models and the goals

of modelling already defined. When goals or

stakeholder types are changed during a modelling

project, one needs to reassess these aspects, and

potentially select a new modelling language, method

or tool.

Sense-making versus corporate memory

We have chosen to differentiate between

modelling for sense-making and for corporate

memory. These concepts can be helpful for

expressing fundamental differences in expectations

to a modelling initiative, often rooted in personal

worldviews emerging as strong opinions on

modelling use and approaches. Totland (1997)

addresses modelling for sense-making and corporate

memory, and the relation to objectivistic and

constructivistic worldviews.

The corporate memory models are reflecting the

organisation, and will exist as a reference point over

time. The sense-making models are used within an

activity in order to make sense of something in an

ad-hoc manner, and will usually not be maintained

afterwards. Sense-making and corporate memory

can be seen as the two endpoints of a scale, where

you have examples of mixed types of models in

between.

These concepts express and explain one type of

differences and disagreements between stakeholders,

drifting within projects, or conflicting approaches in

modelling activities that would otherwise be

expected to have much in common.

The choice of the formality of the modelling

practice should be based on the previously identified

contexts, and where these fit on the line with sense-

making and corporate memory as the two extremes.

Sense-making initiatives generally require a low

level formality of practice.e When the context is

corporate memory, a more formal approach is

needed. The choice of methods, tools and languages,

as well as the choice of managing practice should

reflect the level of formality needed. High formality

requires more managing than low formality.

Table 1: Comparing modelling for sense-making and

corporate memory.

Sense-making Corporate memory

The modelling process is

the goal

The model itself is the

goal

The actual use is often

documented

The intended use is

often documented

Collects the natural

structures

Collects the formal

structures

Identified people

important

General user-roles

important

Less formal methods,

tools and languages

Formal methods, tools

and languages

Roles not important, more

ad-hoc

Roles important.

Often used only for a

specific activity or project

Often re-use across the

organisation

The models are “thrown

away” after use

The models are stored

and re-used

Management of the work

process, models and

modelling not important

Management of the

work process, models

and modelling

important

When identifying the context of the modelling

activity, the optimal position on the sense-making –

corporate memory axis is crucial in order to be able

ICEIS 2006 - INFORMATION SYSTEMS ANALYSIS AND SPECIFICATION

74

to choose appropriate methods, languages and tools,

as well as formality for the managing practice.

4 APPLYING THE FRAMEWORK

During our research we have studied and

documented several cases throughout the

organisation. Through this we have identified

expected and experienced value of modelling work

and models, as well as experienced challenges. In

this chapter we quote some of the reported

(potential) value. We will then look into how the

framework addresses the reported challenges.

4.1 Identifying Potential Value

The stakeholders in our case studies indicated many

valuable outputs in addition to those initially

intended from modelling initiatives and the use of

models. Some of these are:

Communication:

• The high-level models encouraged an

agreement among the management participants

that was vital for the rest of the project, creating

important common references, identification

and enthusiasm.

• The models triggered communication, being

something that everyone could relate to.

• “Three boxes and some arrows: This is a

fantastic communication tool”.

• Communication was initiated and facilitated by

and through the models.

• The models help the participants understand.

Learning:

• The modelling process itself turned out to be a

learning experience for the participating domain

experts, increasing their knowledge about the

processes.

• Through the workshop sessions the participants

learned a lot from interacting with each other,

“new” information was uncovered, and

understanding improved.

• People understand themselves better after a

modelling session.

• The participation in the modelling process of

domain experts is important. The result would

not have been the same if modellers from

outside created the models based on interviews.

• The models helped taking care of and storing

the competence of people in the organisation.

• Modelling is seen as a mechanism to extract

knowledge from people’s heads.

• Training takes less time when process models

were used.

Long-term benefits:

• The process model gives the organisation one

language and one tool for everyone in the

organisation; a common frame of reference.

• Simple and effective diagrams show what is

important for the organisation.

• Through modelling AsIs, and not only ToBe,

best practise is secured and not forgotten.

• The models are used in marketing towards

potential customers.

• There is a marketing value in telling the world

that they have documented processes.

5 CHALLENGES OF

MODELLING AND MODELS

In order to extract more value from the modelling

initiatives and the models, we will in the following

address some of the major identified challenges in

our case studies, and examine how the framework

could solve or indicate a solution to these. For each

paragraph we state the challenge, then how it is

addressed in the framework.

Challenge 1: To keep the models and other

descriptions updated and consistent

Example: It becomes difficult to keep the

models updated as the complexity increase, and the

number of non-integrated tools increases.

Framework application: The framework

suggests careful analysis of the expected model

context before choosing the modelling practice.

Considering the future complexity when choosing

methods, language and tools will make model

management easier. The framework also states the

importance of viewing the management of the

models as a specific activity, stressing the

importance of appointing a model responsible. This

is a different role than the modelling responsible or

the work process responsible (process owner).

Challenge 2: The models are used in situations

they were not intended for.

Example: Models are often created primarily for

one objective. This is challenging when others want

to use them as basis for other work, especially if the

original assumptions are not documented.

Framework application: Through an analysis in

the early phase of the modelling activity, identify the

primary use as well as potential future use and

additional potential value. Accommodation of

indications of future use of the models should be

INCREASING THE VALUE OF PROCESS MODELLING

75

considered when choosing the modelling and the

managing practice.

When in a re-use situation, where a modelling

initiative is going to re-use earlier developed

models, it is important to investigate the context the

models were created for, and what modelling and

managing practice have been used. The decision of a

re-use strategy should be based on this investigation.

Challenge 3: To handle situations when the

modelling starts out as an informal activity, but the

resulting models develop into a process defining

tool. The original language and tools often do not

meet new expectations for the model to be kept

updated, be scaleable, and extendable with new

functionality. The experience is that the chosen tool

and language often do not fit into this new scenario.

Framework application: Awareness of where on

the scale of sense-making versus corporate memory

the models were initially created, and where on the

scale the models have ended up (and where they can

be expected to end up). Sense-making models do not

require a very high level of formality, while

corporate memory models often do. Being conscious

about this will make it easier to identify what has to

be changed in the modelling and managing practice

in order to align with the new situation.

Challenge 4: To produce views of the model

according to different needs and users.

Example: Not being able to produce views of the

models adapted to the specific user and the objective

of the use creates challenges. Specific users and

specific objectives of use require adapted views of

the model. The creation of these is a challenge, both

technically and as regards content.

Framework application: Identify the users and

other stakeholders as parts of the context, analyse

their background knowledge and needs, and what

each of them are going to use the models for.

Methods, language and tools should then be chosen

based on this.

Challenge 5: The models often restrict and limit

the communication.

Example: High level models are easy to agree

upon, but real gaps between the model and current

situation stay uncovered. A model is only one view

of the world. When a model is the communication

generating artefact, the discussions often leave out

those issues not included in the model.

Framework application: Carefully identify the

context and the potential value of the modelling and

models before creating the models. Consciousness

about how to increase the potential value of

communication will potentially help creating a more

fitting model. Awareness of the limitations of a

model and its restrictions is the key.

Challenge 6: To implement the models in the

organisation, particularly outside the modelling

team.

Example: It is a challenge to make the models an

integrated part of the organisation, and to involve the

users to the extent that they feel an ownership and

responsibility for them. When the person doing the

modelling leaves the project and the modelling is

left to the domain experts to finish, implement and

keep updated, experience shows that the focus on the

models often fades. If the modeller leaves too early,

the models may not be implemented.

Framework application: Identify all the expected

users and other stakeholders during the initial phase

of the modelling activity, look into their expected

areas of use and identify potential value. By

choosing a modelling practice to increase the value

across all identified stakeholders, ownership and

usefulness is improved even for stakeholders not

participating in the modelling. If many stakeholders

should be involved in the modelling one can use

techniques such as ”modelling conferences”

(Gjersvik et al 2004)

Challenge 7: To be conscious about distributing

the responsibility of the modelling, models and

processes correctly.

Example: One person was responsible for

everything that had to do with the processes and the

models.

Framework application: The framework makes

distinctions between the activities of managing the

modelling, the models, and the work processes. One

role is related to the management of the modelling,

another to the management of the models, a third to

the management of the work processes.

Challenge 8: During organisational changes,

models may have to be merged as processes are

unified. Different modelling tools and languages

increase the challenge.

Example: Several as-is processes were to be

harmonized and their documenting models merged

into one common process model. The models were

created for different user groups, originated in

different organisational units and also countries. The

modelling processes were also different, involving

different types of people.

Framework application: Such models are most

likely based on different methods, languages and

tools, created for different objectives, uses and users

and other stakeholders. The historic context and the

modelling and managing practice of each of the

models should be investigated in order to establish a

re-use strategy and choose the correct current

modelling and managing practice.

ICEIS 2006 - INFORMATION SYSTEMS ANALYSIS AND SPECIFICATION

76

6 CONCLUSION AND FURTHER

WORK

Based on extensive research across units and

projects in an international company, we have

identified expectations, challenges and experience

pointing to potential increase in value from

modelling activities. To support the realization of

these values, a Modelling Value Framework has

been developed.

The Value Framework has been evaluated against

challenges and experiences of earlier modelling

initiatives, as well as tested in a modelling project.

There are clear indications that further development

and use of the framework will facilitate

communication and alignment within and between

project initiatives and organisational units, thus

potentially increasing value from projects through

improved relevance and quality of results as well as

reduced cost.

Our research has been practically oriented, aiming

towards identification of the important issues in real-

life modelling projects and activities, both with

regard to the actors’ motivation and their experience.

Based on the broad investigations we have made, we

are confident that our results are valid for the case

company.

We expect our findings to be reproducible for other

enterprises of similar size and complexity, but this

still remains to be shown.

Even within the presented enterprise, on a practical

level, there is still a way to go to implement and

collect real-life experience with the framework. Our

studies demonstrate feasibility and advantages of

use, but do not address the actual adoption of the

framework by practitioners not involved in the

development.

We have identified advantages both on a project and

organisational level, and we expect that the project

level advantages will be sufficient to motivate for

the use of the framework – and that the

organisational level advantages can be realized this

way. This assumption however still has to be tested

– and a successful implementation in the whole

organisation will, as a minimum, require a dedicated

dissemination and marketing effort.

REFERENCES

Benbasat, I., Goldstein, D. K. and Mead, M. (1987) "The

case research strategy in studies of informations

systems" MIS Quarterly (11:3) p 369-386

Curtis, B., Kellner, M., Over, J. "Process Modelling,"

Communication of the ACM, (35:9), September 1992,

pp. 75-90.

Dalberg, V., Jensen, S. M., Krogstie, J. Modelling for

organisational knowledge creation and sharing, in

NOKOBIT 2003. Oslo, Norway

Dalberg, V., Jensen, S. M., Krogstie, J. Increasing the

Value of Process Modelling and Models, in

NOKOBIT 2005. Oslo, Norway

Gjersvik, R., J. Krogstie, and A. Følstad, Participatory

Development of Enterprise Process Models, in

Information Modeling Methods and Methodologies, J.

Krogstie, K. Siau, and T. Halpin, Editors. 2004, Idea

Group Publishers.

IDEF-0: Federal Information Processing Standards

Publication 183(1993) Announcing the Standard for

Integration Definition For Function Modelling.

Hammer, M. Reengineering Work, Don’t automate,

Obliterate. Harvard Business Review, 1990

Miles, M. B, and Huberman, A. M. Qualitative Data

Analysis, SAGE Publications 1994

Krogstie, J. and A. Sølvberg, Information systems

engineering - Conceptual modeling in a quality

perspective. 2003, Trondheim, Norway:

Kompendiumforlaget.

Krogstie, J., V. Dalberg, and S.M. Jensen. Harmonising

Business Processes of Collaborative Networked

Organisations Using Process Modelling. in

PROVE'04. 2004. Toulouse, France.

Krogstie, J., Dalberg, V., Jensen, S. M., Using a Model

Quality Framework for Requirements Specification of

an Enterprise Modeling Language, in Advanced

Topics in Database Research, volume 4, Siau K.

Editor. 2005, Idea Group Publishers.

Sedera, W., Rosemann, M. and Doebeli, G. (2003) “A

Process Modelling Success Model: Insights From A

Case Study”. 11th European Conference on

Information Systems, Naples, Italy

Totland, T. (1997). Enterprise Modelling as a means to

support human sense-making and communication in

organizations. IDI. Trondheim, NTNU.

Yin. R. Case study Research. SAGE Publications. 1994

Vernadat, F. (1996) Enterprise Modelling and Integration.

Chapman and Hall.

INCREASING THE VALUE OF PROCESS MODELLING

77