Storytelling on the Internet to Develop

Weak-link Networks: Two case studies “Artistoria”

Bernard Fallery

1

, Carole Marti

2

and Gerald Brunetto

3

1

CREGOR, University Montpellier 2

34000 Montpellier, France

2

CEROM, Groupe SupdeCo

34000 Montpellier, France

3

CREGOR, University Montpellier 2

34000 Montpellier, France

Abstract. Is there an opportunity with Internet to build new weak-link net-

works for sharing knowledge and developing innovation? This article describes

the research carried out in a French Regional Chamber of Trade and Crafts. Our

work consisted of establishing two successive interactive portals collecting sto-

ries: about the experiences of craftsmen using ICT and about the experiences of

collaborative spouses at work. Finally we propose a discussion of the weak

links concept, in order to understand the opportunity with Internet to build new

weak links networks for sharing knowledge and developing innovation.

1 Introduction

Relations between individuals of different social networks promote the ability to

adapt to new situations. The capacity for innovation seems to increase as the ideas are

spread via weak links: the study by Julien and al. (2002) [17] dealing with the innova-

tive behaviour of small companies shows that the most innovative firms are those

who use these weak links most often. Alternating strong links (a network where indi-

viduals have regular contact) and weak links (a network in which individuals have

little contact) at the centre of a social body induces the effect of “structural gaps”

required for new group dynamics and new strategies. So, what are the opportunities

offered by the Internet today in the establishment of new weak-link networks for

knowledge sharing?

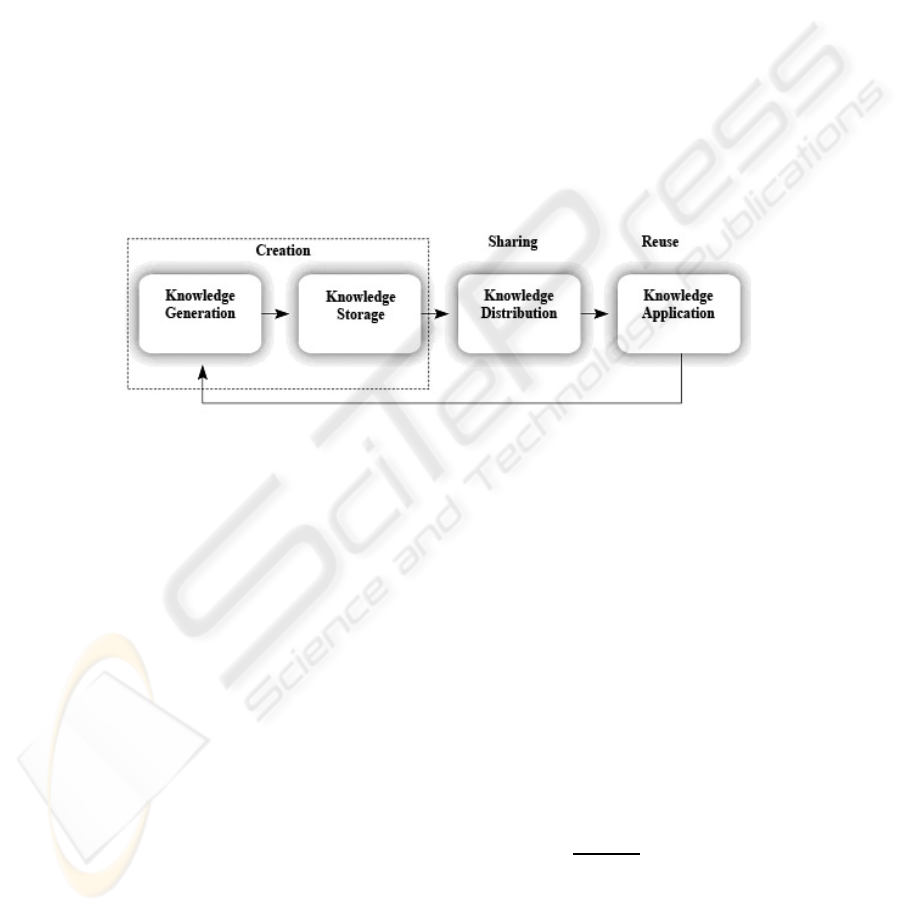

Initially, we will develop the idea of “knowledge lifecycle” by presenting the differ-

ent models proposed by researchers in three successive phases: creation, sharing and

reuse. We will establish the characteristics necessary for a website dedicated to shar-

ing narrated experiences in a weak links network.

Secondly we present Artistoria V.1 the tool that we have developed and implemented

for craftsmen. Thirdly we present Artistoria V.2 the second tool that we are going to

Fallery B., Marti C. and Brunetto G. (2007).

Storytelling on the Internet to Develop Weak-link Networks: Two case studies “Artistoria”.

In Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Human Resource Information Systems, pages 109-119

DOI: 10.5220/0002401601090119

Copyright

c

SciTePress

develop for collaborative spouses at work. Finally we propose a discussion of the

weak links concept, in order to understand the opportunity with Internet to build new

weak links networks for sharing knowledge and developing innovation.

2 The Idea of “Knowledge Lifecycle”: Creation, Sharing and

Reuse

The analysis of the main knowledge management research within organisations can

be used to highlight different interrelated activities: firstly, generation and storage,

then the distribution and the application of experience (De Long and Fahey 2000 [5]

Alavi and Leidner 2001 [1] Gold, Malhotra et al. 2001 [9]). To thus consider knowl-

edge management as knowledge treatment process means that we can represent both

the individual cognitive nature and the socio-cultural nature of organisational knowl-

edge (Alavi and Leidner 2001 [1]). This process is thus based on a veritable knowl-

edge lifecycle:

Fig. 1. Knowledge life cycle, according to Ruggle (1998) [23].

2.1 Creation Phase: Generation and Storage of Knowledge

The two initial stages of generation and storage are closely linked, given that they

establish a body of knowledge to be managed.

The knowledge generation process consists of establishing new content, replacing

existing content, creating new knowledge from existing knowledge, etc. This stage is

generally identified by different terms such as “acquisition, research, generation,

creation, innovation, economic intelligence, capture, tracking, sourcing, etc .”

Then, in the context of a content management system, the challenge of the storage

process is to allow fast and easy access to the stored knowledge: to choose the knowl-

edge for storage, to adopt a suitable storage structure and support, etc. Storage thus

consists of identification, collection and suitable presentation, whatever the context,

of the knowledge acquired or created by an organisation or its members;

For our research we met with craftsmen and with collaborative spouses in craft and

agricultural sectors. The stories were then transcribed and indexed

according to the

different dimensions resulting from our analysis.

65

2.2 Distribution Phase: Knowledge Sharing

Given the scattered nature of the organisational knowledge, organisations must be

able to distribute it, if they wish to reuse previously stored content in different con-

texts (Zander and Kogut 1995 [25] O'Dell and Grayson 1998 [21]). Different authors

agree on two stages in this distribution process. The first stage is externalisation

(Hendriks 1999 [15]) of the knowledge, also referred to as the transmission process

(Davenport and Prusak 1998 [4]) given that it consists of making the information

available to others.

However the critical point becomes what we can call the dilemma of contextualisa-

tion: the fact that knowledge is contextualised gives it more significance (it will be

richer because it is better rooted in the context of its acquisition) but as a result it will

have more cognitive “stability” and will be thus more difficult to share in other con-

texts.

The problem of knowledge externalisation is followed by that of internalisation

(Hendriks 1999 [15]), or the absorption process (Davenport and Prusak 1998 [4]).

This is the second stage of sharing consisting of the “digestion” of the knowledge by

other individuals. The individual who reads or listens to certain information will deal

with it in a two-stage cognitive process: the de-contextualisation then the re-

contextualisation. We may first speak of a “read” step decontextualisation and “re-

write” step recontextualisation (Marti 2005 [20]) when the individual will reconsti-

tute new knowledge in a new context.

Finally the problem of the degree of knowledge contextualisation appears to be

crucial at this point: in most content management systems this must initially be identi-

fied (according to the needs of the future system users). However we suggest the use

of a story structure creation tool which may be used for multiple and interactive

searches, allowing a higher level of flexibility and personalisation: in a way, it is the

user who could manage itself

cognitive distance between “too much” or “too little”

contextual information.

2.3 Re-use Phase: The Application of Knowledge

The final phase is that of reuse consisting of the application of knowledge (Fahey and

Prusak 1998 [8]); Gold, Malhotra et al. 2001 [9]). However this is a concept not often

considered in IS literature because it is difficult to observe. Effectively, this phase

involves recalling the stored information (in a particular place, under a particular

index or classification scheme, or the identification of the expert in the field, etc.) and

the identification of user needs (Duffy 1999 [7]) so that they may really apply the

knowledge. Some authors have, in fact, highlighted the fact that competitive advan-

tage often results from the application of knowledge rather than its possession (Alavi

and Leidner 2001 [1]), however this application process seems to be strongly depend-

ent upon the absorption capacity (Cohen and Levinthal 1990 [3]) of the organisation

members.

For Markus (2001) [19], the reuse of knowledge takes the form of four different ac-

tivities. The first stage is the definition of the research question and is essential for

the success of the reuse stage. The second stage is the search for and the localisation

66

of the expert or expertise. The third stage is the selection of the expert or of the suit-

able consultancy, according to the results of the research. Finally, the fourth stage is

the application of the knowledge in a recontextualisation process (given that the

knowledge was most likely de-contextualised when it was captured or encoded).

This final phase of reuse seems to be crucial for the organisation because it is this that

finally determines the performance of all the knowledge management processes. In

our research, even though we could not observe the final reuse phase, we will study

closely their intentions to reuse

the knowledge.

3 ArtiStoria V.1: A Shared Story Database for Craftsmen

This research is thus being carried out in France in the context of a Regional Chamber

of Trade and Crafts whose objective is to coordinate the action of the five departmen-

tal chambers and to guide the development of the craft sector. The task here consists

of establishing an interactive portal collecting all the stories told by craftsmen regard-

ing their use of ICTs, with the characteristics required of such a sharing tool: sourc-

ing, indexing, consultation and reuse.

In a small company the work of the director is decisive, even exclusive, in the evalua-

tion of potentials, however company directors do not often have the opportunity to

meet “over a coffee” in order to share their experiences. Perhaps for the first time,

the Internet may be used by small companies to enter far off markets and preserve

existing contacts as well as creating new ones.

3.1 ArtiStoria V.1: A Website for Storytelling

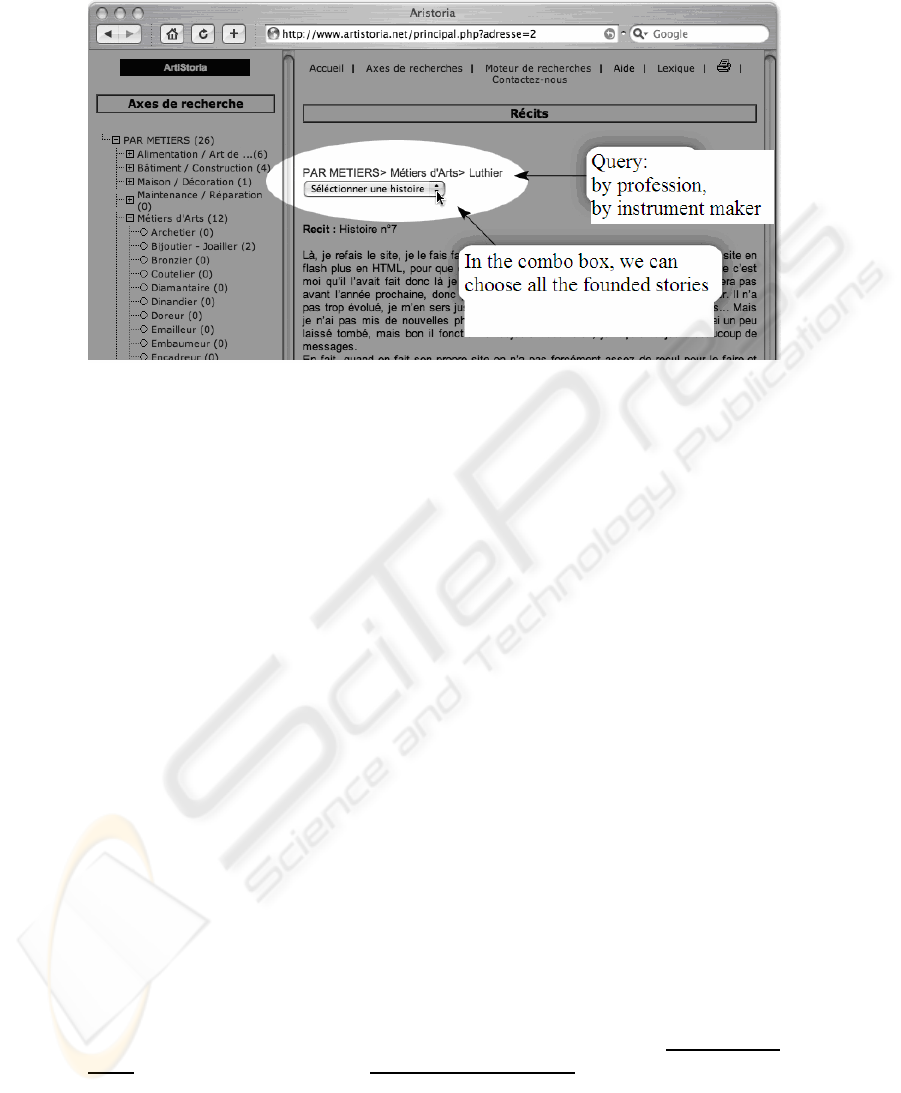

Our examination of the notion of knowledge lifecycle showed us the importance of

the individual’s management of the cognitive distance. We have thus developed the

prototype “ArtiStoria V1” that takes all of these elements into account.

67

Fig 2. Example: Search for stories about instrument maker.

In Artistoria, thanks to these different types of data access (using a full text search of

stories, a full text search of the indexes, by themes, by complete stories, by story

molecules, etc.), a craftsman will be able to search the database more freely: the cog-

nitive distance may be managed according to the ability or difficulty they have

managing the decontextualisation during the ‘read’ phase and the recontextualisation

during the ‘rewrite’ phase.

3.2 Using ArtiStoria V.1: For What Type of Sharing and for What Reuse?

The testing was carried out in three phases. The first phase is the “Before” Interview

where we question the craftsman about their actual use and hopes for the Internet (for

this first phase, eighty seven people participated and all of the interviews were re-

corded and transcribed). Then there is the “During” logbook phase when the crafts-

man is faced with the tool alone, they have to navigate and complete the logbook

progressively, a questionnaire must also be completed so that each applicant is better

characterised (finally forty-eight cases were complete and exploitable). Finally, there

was the “After” Interview phase where we interviewed the craftsman according to

their navigation on ArtiStoria.

Finally we showed that there are two types of cognitive distance: those who reuse

within their sphere of activity and those who reuse outside their sphere of activity.

Then we showed that according to the semantic distance applied by each individual

to each particular piece of knowledge, they would use a smaller or larger part of the

knowledge: “I adopt directly”, “I adapt” and “I transform”.

We can therefore cross-reference the different types of reuse with the different modes

of cognitive distance. The scenarios are then defined according to the cognitive dis-

tance taken by individuals and the way in which they reuse the knowledge:

68

The cross-reference of these two dimensions results thus in six possible scenarios:

Table 1. The possible scenarios.

I adopt di-

rectly

I

adapt

I transform

Within (1) (3) (5)

Outside (2) (4) (6)

The scenario “I ADOPT DIRECTLY, inside”: 12 cases studied

The individuals in this category do not isolate the knowledge from its context, in

other words they have difficulty decontextualising. Consequently, they “recontextual-

ise” easily to translate the knowledge to their own professional context. The common

factor that we found among all of these craftsmen is that they are only occasional

users of Internet, either because they are new to Internet, because their profession

does not really involve Internet use or simply because they have no desire to develop

this use.

The scenario “I ADAPT, inside and outside”: 15 cases studied

This scenario groups the craftsmen who have no problem handling cognitive distance.

They are capable of reading the stories inside and outside of their context. Regard-

ing reuse, they intend to ADAPT the knowledge. The important point of this scenario

is that the craftsmen are capable of reading any type of story with sufficient distance

to extract the interesting information. They decontextualise and recontextualise. They

do not speak to us about specific examples but rather a general use which they find

interesting and that they transpose to their own professional context.

Most use the Internet on a daily basis for their profession, in particular for profes-

sionals in the areas of printing and graphics where the Internet is used daily to search

for professional resources (typologies, logos, images). For professions such a baker,

delicatessen, chocolate maker or instrument maker the Internet is an additional tool

for their activity and used for the most part as client communication tool: they usually

have a site. Lastly, for professions such as heating specialists, plumbers or bricklay-

ers the use is different: craftsmen use the Internet to communicate with suppliers, to

order goods or exchange photographs of sites.

The scenario “I TRANSFORM, inside and outside”: 10 of cases studied

This category of “transformers” is quite different from the two previous categories.

They read stories inside and outside of their professional context, however they

TRANSFORM knowledge, more than simply adapting it they completely rephrase it.

The craftsman will systematically decontextualise then recontextualise and imagine

something new for their own activity. It is interesting to note that this is the only

category in which certain craftsmen did not only search by profession but also used

key words, links or other references. Regarding Internet use, all use Internet on a

daily basis for their work. They are similar to those in the previous scenario however

they seem to be more familiar and experienced in the area of computers.

69

4 Artistoria V.2: Structuring the Lifetime of Collaborative

Spouses

This second project is in progress regarding a second version of ArtiStoria. It is a

European project EQUAL in collaboration with the network of Chambers of Trade

and Crafts and the agricultural sector with the aim of providing a common base for all

the collaborative spouses. The tool will be used to form an initial knowledge database

that, using keywords, may be consulted on the Internet. This knowledge management

tool may be used to benefit from experiences in order to facilitate location, preserva-

tion, development and updating. It will facilitate an inventory of best life practices:

within the framework of a monitoring method to support thinking and actions to be

taken and or the transfer of knowledge and best practices between collaborative

spouses. One of the objectives for the international partnership will be to feed the

database and thus constitute, over time, a European wide knowledge management

tool.

4.1 Data Analysis for Account Structure

In this case we collect 96 different stories directly from people in their homes and we

used the Alceste, software which is based on syntactic analysis of repetition and co-

occurrence (the simultaneous occurrence of two linguistic units).

The 96 stories are automatically divided into 1023 elementary units so that each ECU

(Elementary Context Unit) contains a different number of analysed words. Finally

Alceste retain 616 representative ECUs to be divided into classes for a descending

hierarchical classification or DHC by successive division of the text: the first class

analysed includes all of the retained context units, then, at each stage, all of the re-

maining classes are divided in two, maximising the Chi-squared test.

The following are typical ECUs:

ECU Khi2 Typical Elementary Context Units of Class 1:

664 27 We tried to separate our work life and our family life, etc. our

friends, our hobbies, even if they are few, but we still manage to have some

recovery time.

246 24 for example, on Wednesdays we did not work. We did not go to

the office unless it was really urgent. It is both positive and negative. It is

true that we think that we can do it later. At the same time, we must try all

the same. For that reason I try to fix hours for myself.

Five classes were described according to the words used to define them, for example:

Class 1: Home-Family (117 ECU classified out of 616, that is 19%): to try, thing,

available, house, organise, important, to separate, function, project, family, week,

office, together, week-end, daily …

Class 2: Timetable (103 ECU classified out of 616, that is 16%): morning, to eat,

evening, afternoon, obligation, educational, traffic, to leave, midday, school, washing,

child, sister, meal, quarter…

70

Class 3: Business (138 ECU classified out of 616, that is 22%): client, Internet, com-

puter, supplier, to listen, account, to call, structure, schedule, place, message, feed-

back, to explain, satisfied, recent…

A hierarchical analysis by ascending classification (AHC) is used to define various

sub-classes in each class. Here we will give only one example in Class 2 “Timetable”

that may be broken down into: evening, obligations, meals, problems, homework

support, weekends.

The contingency tables were then submitted to a factorial correspondence analysis

(FCA) by cross-referencing the retained vocabulary with the ECU classes. Here the

objective is to obtain a schematic spatial representation of inter-class relationships:

- firstly, on the horizontal axis 1 (indicating 34% of the total dispersion) we see that

“House-Family” (right hand side) is opposed to “Status” (left hand side)

- on the vertical axis 2 (indicating 28% of the total dispersion) we note that “Timeta-

ble” and “Status” (above) are clearly opposed to “Business” and “Training”.

4.2 Development of the Version Artistoria V.2

Accounts and stories relate people to social events, procedures and organisations. For

the past twenty years, the concept of accounts has been increasingly used in social

science. Stories, in particular, are also becoming more popular both in the area of

management science (Marti (2005)[20]), and in the sphere of knowledge management

and information science.

We consider this coming together between management sciences and “story sciences”

interesting given that the use of stories is a familiar human ability. Accounts have a

key role in social sciences because they represent a great method of understanding a

situation, and to order a collection of information: people think more in a “narrative”

manner rather than an “argumentative” or “paradigmatic” manner. The narrative or-

ganisation of a personal experience is a particularly interesting way to convey under-

standing.

At the present stage of the process, we can offer a statistic method to divide the ac-

counts into units (96 stories were used to structure 616 account units). We can now

create “reconstructed” stories using these units and each one of these reconstructed

stories will have the characteristics of a category. One of the characteristics of the

Artistoria V.2 will be the exchange of comments on each story online using an anno-

tation server. This work clearly involves several disciplines: language science (narra-

tology), computer science (annotations, ontology, Semantic Web), information and

communication sciences (cognition, uses, Internet media), and management science

(appropriation, knowledge management, reuse, innovation).

5 Discussion: Internet, An Opportunity for Weak Links

Networks?

Granovetter (2000) [12] defines weak link networks as those where individuals have

little interaction over time, low emotional intensity, little trust and few reciprocal

71

services. The idea of an "interpersonal link" is at the heart of his analysis: “a link

whose strength is a combination (probably linear) of time, emotional intensity, inti-

macy (mutual trust) and the reciprocal services that define it" (Granovetter 2000, p.

46-47) [12]. The absence of strong links between two groups even constitutes what

Burt (1992) [2] called a "structural gap". The "bridge", that is the weak link between

two independent groups, is extremely valuable since it generates informational vari-

ety in each group. The more structural gaps there are in a network, the higher the

informational benefit of the network will be. By becoming a member of an associa-

tion, an individual acquires a virtual social capital and potentially has access to all

members of the community without necessarily being personally acquainted with

each one.

In the case of craftsmen, the role of leader is decisive if not exclusive and it is thus

extremely important for the craftsman to adapt the tools that will help them better

play their role as interface: competition advantage may therefore originate not from

the creativity of one individual but from the ability to build an innovative network of

“weak-link” contacts (Julien, Andriambeloson et al. 2002) [17]. Unlike traditional

strong-link networks (that could consist of, for example, a chartered accountant, a

banker, suppliers, customers, a Chamber of trade, etc.) these weak-link networks are

sociologically distanced from the leader (training courses, management clubs, profes-

sional trade shows, trainee welcome programmes, exhibitions, online training, senior

sponsorships, etc.). Internet may thus multiply the capacities of companies provided

that we know how to benefit from this: technological awareness, international links,

new contacts, opportunity strategies, often commercial and incremental innovations,

local production systems, etc. Consequently, our study shows that the use of stories

and is a good knowledge sharing method and has clarified the ideas of cognitive dis-

tance and semantic density by identifying three types of reuse scenarios.

In the case of the project “Recognition and independence of collaborative spouses”

the objective is to remove the obstacles for a concrete recognition of the spouses of

entrepreneurs. This is to encourage the participation of women in economic life and

employment, to promote the place of spouses in the company and in the representa-

tive professional authorities in order to guide each spouse in the organisation of their

professional work so that each member of a couple may, under the best of conditions,

develop a balance between family life and professional activity. Thus the Internet

may be used to create weak links by research common to crafts and agriculture based

on the inventory of needs in the form of “life stories”. Our study shows that stories

are still an excellent manner to share experiences, it defines the idea of indexing sto-

ries, highlights the need to create a comments annotation system and the need to make

multimedia documents available.

72

References

1. Alavi, M. and D. E. Leidner (2001). "Review : knowledge management and knowledge

management systems : conceptual foundation and research issues." MIS Quarterly 25(1):

107-136.

2. Burt, S. R. (1995). "Le capital social, les trous structuraux et l'entrepreneur." Revue Fran-

çaise de Sociologie XXXVI(4): 599-628.

3. Cohen, W. M. and D. A. Levinthal (1990). "Absorptive capicity : a new perspective on

learning and innovation." Administrative Science Quarterly 35(1): 128-152.

4. Davenport, T. H. and L. Prusak (1998). Working knowledge: how organizations manage

what they know. Boston, Harvard Business School Press.

5. De Long, D. W. and L. Fahey (2000). "Diagnosing cultural barriers to knowledge

management." The Academy of Management Executive 14(4): 113-127.

6. Dibiaggio, L. et M. Ferrary (2003). "Communautés de pratique et réseaux sociaux dans la

dynamique de fonctionnement des clusters de hautes technologies." Revue d'économie in-

dustrielle(103): 111-130.

7. Duffy, D. (1999). "It takes an e-village." CIO Enterprise Magazine.

8. Fahey, L. and L. Prusak (1998). "The eleven deadliest sins of knowledge management."

California Management Review 40(3): 265-275.

9. Gold, H. A., A. Malhotra, et al. (2001). "Knowledge management : an organizational

capabilities perspective." Journal of Management Information Systems 18(1): 185-214.

10. Granovetter, M. (1973). "The strength of weak ties." American Journal of Sociology 78(6):

1360-1380.

11. Granovetter, M. (1985). "Economic action and social culture : the problem of embedded-

ness." American Journal of Sociology 78(6): 481-510.

12. Granovetter, M. (2000). Le marché autrement : les réseaux dans l'économie. Paris, Desclée

de Brouwer.

13. Grant, R. M. (1996). "Prospering in dynamically-competitive environnements :

organizational capability as knowledge integration." Organization Science 7(4): 375-387.

14. Hansen, M. T. (1999). "The search-transfer problem : the role of weak ties in sharing

knowledge across organization subunits." Administrative Science Quarterly 44(1): 82-111.

15. Hendriks, P. (1999). "Why share knowledge? The influence of ICT on the motivation for

knowledge sharing." Knowledge and Process Management 6(2): 91-100.

16. Jovanovic, B. (2001). "New technology and the small firm." Small Business Economics

16(1): 53-55.

17. Julien, P. A., E. Andriambeloson, et al. (2002). Réseaux, signaux faibles et innovation

technologique dans les PME du secteur des équipements de transport terrestre. 6ème

congrès international francophone de la PME, HEC Montréal.

18. Leonard-Barton, D. et D. K. Sinha (1993). "Developer-user interaction and user satisfaction

in internal technology transfer." Academy of Management Journal 36(5): 1125-1139.

19. Markus, L. (2001). "Toward a theory of knowledge reuse: types of knowledge reuse

situations and factors in reuse success." Journal of Management Information Systems

18(1): 57-91.

20. Marti, C. Fallery B. (2005). “Does the Knowledge management have a sense for the small

companies? The storytelling between craftspeople”. EMCIS, 8-10 Juin 2005, CAIRO

21. O'Dell, C. and J. C. Grayson (1998). "If only we knew what we know." California

Management Review 40(3): 154-174.

22. Ruef, M. (2002). "Strong ties, weak ties and islands : structural and cultural predictors of

organizational " Industrial and Corporate Change 11(3): 427-449.

73

23. Ruggles, R. (1998). "The state of the notion : knowledge management in practice."

California Management Review 40(3): 80-89.

24. Stein, E. W. and V. Zwass (1995). "Actualizing organizational memory with information

systems." Information Systems Research 6(2): 85-117.

25. Zander, U. and B. Kogut (1995). "Knowledge and the speed of the transfer and imitation of

organizational capabilities : an empirical test." Organization Science 6(1): 76-92.

74