USABILITY COST-BENEFIT MODELS

Different Approaches to Usability Cost Analysis

Mikko Rajanen

Department of Information Processing Science, University of Oulu, PO Box 3000, FIN-90014, Oulu, Finland

Keywords: Usability, Usability Cost-Benefit Models, Cost of Usability.

Abstract: There are few development organizations that have integrated usability activities as an integral part of their

product development projects. One reason for this might be that the costs and benefits of usability activities

are not visible to the management. In this paper the author analyses some of the characteristics of the

published usability cost-benefit analysis models. These models have different approach for identifying the

costs of usability.

1 INTRODUCTION

Usability is defined as one of the main product

quality attributes for the international standard ISO

9126. It means the capability of the product to be

understood by, learned, used by and attractive to the

user, when used under specified conditions (ISO

9126, 2001). Another usually referred to definition

of usability is in standard ISO 9241-11, where

usability is defined as: “The extent to which a

product can be used by specified users to achieve

specified goals with effectiveness, efficiency and

satisfaction in a specified context of use” (ISO

13407, 1999).

Usability has many potential benefits for a

development organization such as increased

productivity and customer satisfaction. But even

today there are quite a few product development

organizations reportedly having incorporated

usability activities in their product development

process. Bringing usability activities into the product

development life cycle has been a challenge since

the beginning of usability activities over fifty years

ago (Ohnemus, 1996).

One reason for this is that the benefits of better

usability are not easily identified or calculated.

Usability engineering has been competing for

resources against other project groups who do have

objective cost-benefit data available for management

review (Karat, 1994). The purpose of this paper is to

categorise the usability cost-benefit analysis models

based on their approach for the usability cost

analysis. This broad topic is approached through a

following research question:

How do the usability cost-benefit models

approach and categorise the cost of better usability?

The cost-benefit analysis is a method of

analysing projects for investment purposes (Karat,

1994). It embodies the idea that decisions should be

based on comparing the advantages and

disadvantages of an action. Technical and financial

data is gathered and analysed about a given business

situation or function. This information assists in

decision making about resource allocation.

The method has three steps and it proceeds as

follows (Burrill and Ellsworth, 1980):

1. Identify the financial value of expected project

cost and benefit variables.

2. Analyse the relationship between expected costs

and benefits using simple or sophisticated

selection techniques.

3. Make the investment decision.

Development management often sees usability

activities as a potential risk to the deadline of their

projects. It is difficult to implement usability

activities in development projects without the

support of the business management. Management

level support for usability activities in development

projects is achieved if the benefits of better usability

can be identified and calculated. Better usability can

for example speed up the products market

introduction and acceptance (Conklin, 1991) and

increase revenues (Wixon and Jones, 1991). In the

usability cost-benefit analysis of usability activities,

332

Rajanen M. (2007).

USABILITY COST-BENEFIT MODELS - Different Approaches to Usability Cost Analysis.

In Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems - HCI, pages 332-336

DOI: 10.5220/0002407803320336

Copyright

c

SciTePress

expected costs (e.g., personnel costs) and benefits

(e.g., lower training costs) are identified and

quantified (Karat, 1994).

There are many published models for calculating

usability benefits, and as many ways of identifying

the benefits. A business benefit is a positive return

that the development organisation expects to obtain

as a result of an investment. There has been some

discussion in publications about the potential

business benefits of usability, but most of them are

focused on case studies of usability benefits or the

overall aspects of usability cost-benefit analysis. In

this research, the author analysed the differences and

characteristics between some of the published

usability cost-benefit models.

Calculating the cost of better usability is fairly

straightforward if the necessary usability tasks are

identified (Mayhew and Mantei, 1994). The actual

cost of usability can be divided into initial costs and

sustaining costs (Ehrlich and Rohn).

2 OVERVIEW OF USABILITY

COST-BENEFIT MODELS

There are surprisingly few published models for

analysing the benefits of usability in development

organizations. Most of the existing usability benefit

models analysed in this paper was selected from the

book Cost-Justifying Usability by Bias and Mayhew.

This book was published in 1994, but it is still the

best source of different usability cost-benefit

models. The analysed models taken from Cost-

Justifying Usability were selected for this report

because they represent the overall variety of

different views for usability benefit analysis. The

second edition of the book was published 2005 but it

did not change the usability cost-benefit models

(Bias and Mayhew 2005).

Bevan (Bevan, 2000) and Donahue (Donahue,

2001) have published two of the latest usability cost-

benefit analysis models. These models were selected

for this analysis because they have a slightly

different point of view on different benefits of

usability. The Bevan’s model also estimates

potential usability benefits in four different product

life cycles while other analysed models do not have

such a clear point of view about benefits in product

life cycles.

2.1 Ehrlich and Rohn

Ehrlich and Rohn analyse the potential benefits of

better usability from the point of the view of the

vendor company, corporate customer and end user

(Ehrlich and Rohn, 1994). They state that by

incorporating usability activities into a product

development project, both the company itself and its

customers gain benefits from within certain areas.

When compared to the other usability benefit models

analysed in this paper, Ehrlich and Rohn present the

most comprehensive discussion about different

aspects of usability cost-benefits.

According to Ehrlich and Rohn a vendor

company can identify benefits from three areas:

1. Increased sales

2. Reduced support costs

3. Reduced development costs.

In some cases, a link between better usability and

increased sales can be found, but usually it can be

difficult to relate the impact of better usability

directly to increased sales. One way to identify the

impact of usability on sales is to analyse how

important a role usability has in the buying decision.

The cost of product support can be surprisingly

high if there is a usability problem in an important

product feature, and the product has lots of users.

Better usability has a direct impact on the need for

product support and therefore, great savings can be

realized through a reduced need for support. By

focusing on better product usability and using

usability techniques, a vendor company can cut

development time and costs. The corporate customer

can expect benefits when a more usable product

reduces the time that end users need for training.

And in addition to official training, there are also

hidden costs for peer-support. End users often seek

help from their expert colleagues, who therefore

suffer in their productivity. It is estimated that this

kind of hidden support cost for every PC is between

$6.000 and $15.000 every year (Bulkeley, 1992).

End users are the final recipients of a more

usable product. According to Ehrlich and Rohn,

increased usability can result in higher productivity,

reduced learning time and a greater work satisfaction

for the end user. The end-user can benefit from

higher productivity when the most frequent tasks

take less time.

2.2 Bevan

Bevan estimated the potential benefits of better

usability for an organization to be during

USABILITY COST-BENEFIT MODELS - Different Approaches to Usability Cost Analysis

333

development, sales, use and support (Bevan, 2000).

A vendor can gain benefits in development, sales

and support. A customer can benefit in use and

support. When a system is developed for in-house

use, the organization can identify benefits for

development, use and support. In each category,

there are a number of possible individual benefits

where savings or increased revenue can be

identified. The total amount of benefits from better

usability can be calculated by adding all the

identified individual benefits together. Bevan mainly

discusses usability benefits derived from increased

sales, a lower need for training and increased

productivity. Benefits accruing due to decreased

development time are identified but they are not

discussed in detail.

2.3 Donahue

Donahue’s usability cost-benefit analysis model

(Donahue, 2001) is based on the model of Mayhew

& Mantei (Mayhew and Mantei, 1994). In this

model the costs and benefits of better usability are

analysed through costs for development organisation

and benefits for customer organisation. According to

Donahue the most important aspect of usability cost-

benefit analysis is calculating the savings in

development costs.

2.4 Karat

Karat approaches usability benefits through a cost-

benefit calculation of human factors at work (Karat,

1994). This viewpoint is different from other

analysed usability benefit models. There are some

examples of identified potential benefits. The

benefits are identified as:

– Increased sales

– Increased user productivity

– Decreased personnel cost through smaller staff

turnover.

A development organization can gain benefits

when better usability gives a competitive edge and

therefore increases product sales. A customer

organization can gain benefits when end user

productivity is increased through reduced task time

and when better usability reduces staff turnover.

Karat describes a usability cost-benefit analysis of

three steps. In the first step, all expected costs and

benefits are identified and quantified. In the second

step, the costs and benefits are categorized as

tangible and intangible. The intangible costs and

benefits are not easily measured, so they are moved

into a separate list. The third step is to determine a

financial value for all tangible costs and benefits.

Karat also links the usability cost-benefit analysis

with business cases. Business cases provide an

objective and explicit basis for making

organisational investment decisions (Karat, 1994).

2.5 Mayhew and Mantei

Mayhew and Mantei argue that a cost-benefit

analysis of usability is best made by focusing

attention on the benefits that are of the most interest

to the audience for the analysis (Mayhew and

Mantei, 1994). The relevant benefit categories for

the target audience are then selected, and the

benefits are estimated. Examples of relevant benefit

categories are given for a vendor company and

internal development organization. The vendor

company can benefit from:

– Increased sales

– Decreased customer support

– Making fewer changes in a late design life cycle

– Reduced cost of providing training.

The benefits for an internal development

organization can be estimated from the categories of

increased user productivity, decreased user errors,

decreased training costs, making fewer changes in a

late design life cycle and decreased user support. To

estimate each benefit, a unit of measurement is

chosen for the benefit. Then an assumption is made

concerning the magnitude of the benefit for each

unit of measurement. The number of units is then

multiplied by the estimated benefit per unit.

3 USABILITY COST FACTORS

The costs of better usability can be categorized into

three groups: one-time costs, recurring costs and

redesign costs. One-time costs or initial costs cover

for example the costs of establishing a laboratory for

usability testing. Recurring costs are for example the

salary costs of the usability professionals employed

in the usability testing laboratory. Redesign costs

cover the costs of redesigning the prototypes for

example based on the usability test results (Mayhew

and Mantei, 1994).

3.1 One-Time Costs

Ehrlich & Rohn, Mayhew & Mantei and Donahue

identify one-time costs and provide some example

calculations of one-time costs of usability work.

ICEIS 2007 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

334

These models do not provide further documentation

about an overall cost calculation. Karat identifies the

one-time costs but do not provide further

documentation or example calculations (Karat,

1994). Bevan does not identify one-time costs of

better usability at all (Bevan, 2000).

3.2 Recurring Costs

All of the analysed usability cost-benefit models

identify the recurring costs of better usability as one

factor in usability cost-benefit analysis. Ehrlich &

Rohn and Mayhew & Mantei provide some example

calculations and further discussion of recurring

costs. These models do not provide further

documentation about calculation of recurring

usability costs. Karat, Bevan and Donahue identify

the recurring costs of usability work but they do not

provide example calculations or further discussion

about cost calculation.

3.3 Redesign Costs

The costs of prototype redesign are different from

other two usability cost factors that these costs

usually affect a product development project

directly. For example the product development

project redesigns prototypes for the usability testing.

Mayhew & Mantei identify the prototype related

redesign costs and provide some example

calculations about this cost factor but there is no

further documentation about calculating the redesign

costs. Karat identifies this cost factor but does not

provide any example calculations or further

discussion.

3.4 Comparing the Usability

Cost-Benefit Models

There are some significant differences between the

analysed usability cost-benefit models in identifying,

documenting and providing example calculations for

one-time costs, recurring costs and prototype

redesign costs.

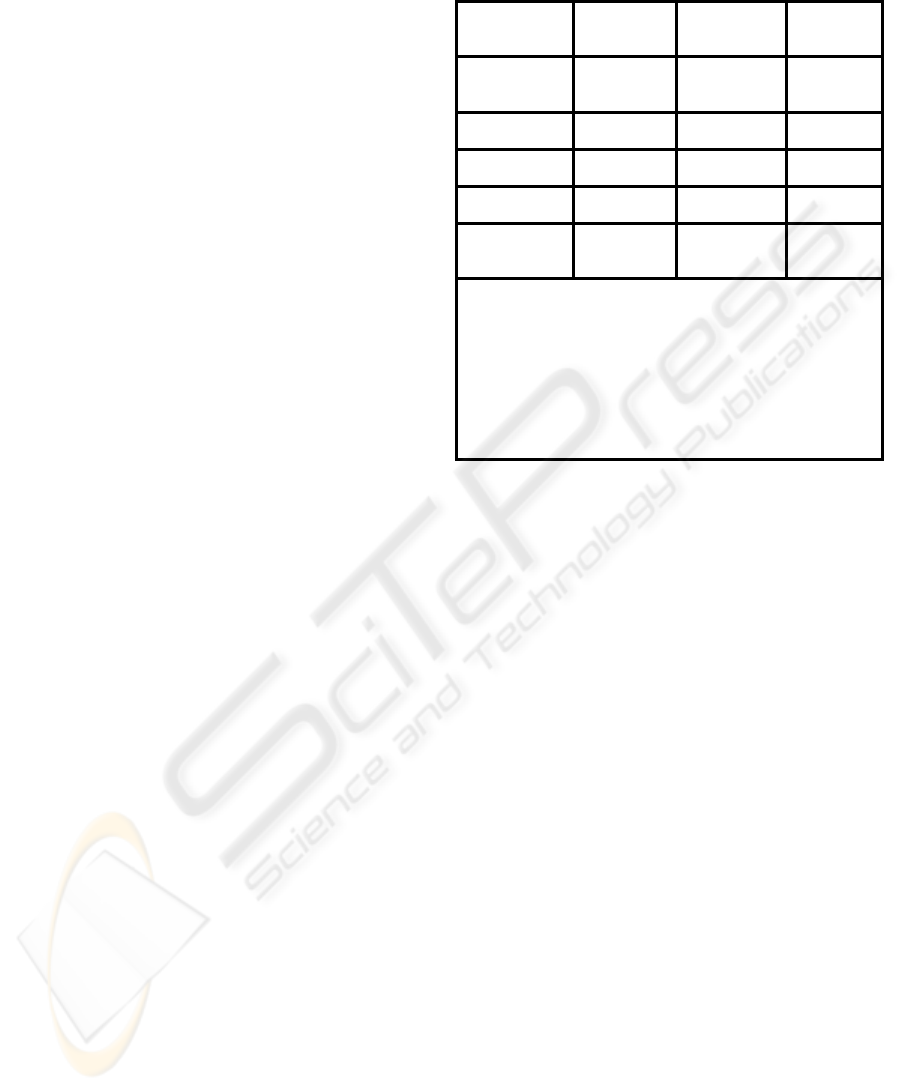

The comparison of the usability cost-benefit

models and cost factors presented above is

summarised in table 1.

Table 1: The extent of which the usability cost-benefit

models identify and document the costs of usability.

Cost factors

One-time

costs

Recurring

costs

Redesign

costs

Ehrlich &

Rohn

XX XX O

Bevan O X O

Donahue XX X O

Karat X X X

Mayhew &

Mantei

XX XX XX

XX = The usability cost factor are identified and

some example calculations are provided. No

further documentation how to do the calculations.

X = The usability cost factor are identified but no

example calculations or further documentation is

provided.

O = The usability cost factor is not identified.

4 CONCLUSIONS

There are few development organizations that have

integrated usability activities as an integral part of

their product development projects. One reason for

this might be that the costs and benefits of usability

activities are not visible to the management. In this

paper the author analysed how the published

usability cost-benefit analysis models identify and

document the usability cost factors.

None of the analysed usability cost-benefit

models cover the one-time costs factor fully by

identifying the cost, documenting the cost

calculation and providing some example

calculations. Ehrlich & Rohn, Donahue and Mayhew

& Mantei cover the one-time costs factor best

though they lack in either example calculations or

documentation. Karat identifies the one time costs

but does not provide either examples or further

discussion. Bevan does not identify one-time costs at

all.

None of the analysed usability cost-benefit

models cover the recurring costs factor fully. Ehrlich

& Rohn and Mayhew & Mantei cover the recurring

costs best though they lack in either example

calculations or further documentation. Bevan,

Donahue and Karat identify the recurring costs

factor but do not provide example calculations or

further discussion.

USABILITY COST-BENEFIT MODELS - Different Approaches to Usability Cost Analysis

335

None of the analysed usability cost-benefit

models cover the prototype redesign costs factor

fully. Mayhew and Mantei cover the redesign costs

factor best but lack in documenting the redesign cost

calculation. Karat identifies the prototype redesign

costs factor but does not provide example

calculations or further discussion about this cost

factor.

REFERENCES

Bevan, N. Cost Benefit Analysis version 1.1. Trial

Usability Maturity Process. Serco Usability Services.

Bias, R., Mayhew, D. 2005. Cost-Justifying Usability,

Second Edition: An Update for the Internet Age.

Bulkeley, W. M., 1992. Study finds hidden costs of

computing. The Wall Street Journal, Nov.

Burrill, C., Ellsworth, L. 1980. Modern Project

Management: Foundations for Quality and

Productivity. Burrill-Ellsworth, New Jersey.

Conklin, P. 1991. Bringing Usability Effectively into

Product Development. In Human Computer Interface

Design: Success Cases, Emerging Methods, and Real-

World Context, Boulder, Co. July

Donahue, G. 2001 Usability and the Bottom Line. IEEE

Software.

Ehrlich, K., Rohn, J. 1994. Cost Justification of Usability

Engineering: A Vendor’s Perspective. In Bias, R.,

Mayhew, D. Cost-Justifying Usability. Academic

Press, pp 73-110.

ISO 13407. 1999. Human-centered design processes for

interactive systems. International standard.

ISO/IEC 9126-1. 2001. Software Engineering, Product

quality, Part 1: Quality model. International Standard.

Karat, C-M. 1994. A Business Case Approach to Usability

Cost Justification. In Bias, R., Mayhew, D. Cost-

Justifying Usability. Academic Press, pp 45-70.

Mayhew, D., Mantei, M. 1994. A Basic Framework for

Cost-Justifying Usability Engineering. In Bias, R.,

Mayhew, D. Cost-Justifying Usability. Academic

Press. 1994. pp 9-43.

Ohnemus, K. 1996. Incorporating Human Factors in the

System Development Life Cycle : Marketing and

Management Approaches. IPCC96.

Wixon, D., Jones, S. 1991. Usability for fun and profit.

Internal report. Digital Equipment Corporation.

ICEIS 2007 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

336