ON PSEUDONYMOUS HEALTH REGISTERS

While they Work as Intended, they are Still Controversial in Norway

Herbjørn Andresen

Norwegian Research Centre for Computers and Law, University of Oslo, Norway

Keywords: Confidentiality, Privacy Regulation, Data Security, Pseudonymity, Public Health Policy.

Abstract: Patient health data has a valuable potential for secondary use, such as decision support on a national level,

reimbursement settlements, and research on public health or on the effects of various treatment methods.

Unfortunately, extensive secondary use of data is very likely to have disproportionate negative impact on the

patients’ privacy. Traditionally, privacy regulations require a balancing process; the use of data should be

minimized and kept within a level where proportionate privacy is maintained. An alternative strategy is to

use technological remedies to enhance privacy protection. Norwegian health data processing regulation

prescribes four different ways of organising health registers (anonymous, de-identified, pseudonymous or

fully identified data subjects). Pseudonymity is the most innovative of these methods, and it has been

available as a legitimate means to achieve extensive secondary use of accurate and detailed data since 2001. Up

to now, two different national health registers have been organised this way. The evidence from these

experiences should be encouraging: Pseudonymity works as intended. Yet, there is still discernible

reluctance against extending the pseudonymity principle to encompass other national health registers as

well.

1 INTRODUCTION

Any patient must accept some processing of his

personal data, within the confines of a medical

treatment. Some data are collected from the patient

himself, and some data may be generated along the

course of the treatment. The confidentiality will

inevitably be at risk; the risks need to be monitored

and handled. Privacy regulations and data security

measures, along with professional ethics, safeguard

against unwarranted processing and filing practises,

and against deliberate misuse.

Privacy is also at stake when the patient’s health

data is used beyond the appointed medical treatment.

Such use could be named secondary purposes for

processing data. The subject matter of this paper is a

particular variety of secondary purposes, namely a

group of national health data registers. A register is a

service that comprises a database, an operating

organisation, and a legal authority defining respons-

ibilities, duties to report to the register, restrictions

on use and so on. In colloquial language the term

register is normally taken to mean the database

itself. The organisation and the legal authority are

implied.

The registers have two important features, from a

privacy point of view. Firstly, they are centralised

systems, containing aggregated data. Personal health

data are collected from different hospitals or other

treatment entities. As Norway is a small country,

centralised registers usually cover the entire nation.

The procedure of collecting the data could either be

by electronic exchange or by printed reports which

are re-typed into the centralised system.

Secondly, the data is collected and processed for

secondary purposes, somewhat remote from the

patient’s immediate needs and interests. Roughly

stated, these secondary purposes are governmental

administration and medical research. Governmental

administration includes both macro-level decision

support and reimbursement control procedures. The

demand for data is, at least in principle, limited and

foreseeable. Medical research will also in most cases

demand a stable amount of foreseeable data, yet in

some cases it could be beneficial to use excess data

or to perform inventive couplings involving different

data sources. The future value of ingenious data

mining is by definition unknown.

Regulations, security measures and ethics are of

course at least as required for the registers as they

59

Andresen H. (2008).

ON PSEUDONYMOUS HEALTH REGISTERS - While they Work as Intended, they are Still Controversial in Norway.

In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Health Informatics, pages 59-66

Copyright

c

SciTePress

are for data in the immediate care systems. In

addition, the registers are vulnerable to expansions

of their stated and legitimate purposes. Proponents

of strict privacy regulations warn against “the

slippery slope”. It can be increasingly difficult on

each particular occasion to turn down a proposition

for extended use of a register. Such propositions

often serve legitimate purposes, which is to achieve

new and even benign goals more easily. Conse-

quently, the patients’ privacy is in danger of being

scooped out in the long run.

1.1 The Adage of Norway’s Favourable

Conditions for Health Registers

Norway introduced a national identity number quite

early. Starting in 1964, Statistics Norway assigned a

unique 11-digit identification number to every

individual. The primary purpose of the national

identity number was to produce accurate statistics.

Large public agencies, such as the Tax Admini-

stration and the National Insurance Administration,

soon adopted the new unique identification number.

No one imagined the vast future use of this new

identity number. There was no explicit legal support

for it, and hence there were no expressed restrictions

on its use either (Selmer, 1992).

Due to the lack of restrictions on the use of

population register data in the early years, the

identity number is now the key to personal data in

thousands of public as well as private IT-systems

throughout the country, including primary health

care systems and hospital systems. Most Norwegians

will have to type or pronounce his unique personal

identity number to some electronic apparatus (or to

its human gatekeeper) several times a week. It is

“open sesame” to enter both caves of treasures and

caves of dung.

Due to the widely used national identity number,

Norway may have favourable conditions for national

health registers. Because the identity numbers are

used in systems that are vital to virtually everyone,

the data quality of the primary systems reporting to

the registers almost takes care of itself. The registers

could technically be suitable for collecting perfectly

linkable data from the cradle to the grave.

However, the early years of vastly expanding the

use of national identity numbers was succeeded by

almost three decades of efforts to impart restrictions

on their use. Lawful use of the national identity

number is subject to a “norm of necessity”. Roughly,

it goes like this: When an exact identification is

necessary, then the controller ought to use a unique

identifier, while using the same unique identifier

would be unlawful when unique identification is not

necessary (this is a crude simplification, on my own

behalf, of the Personal Data Act section 12). The

result from these efforts to limit the lawful use of

unique identifiers has not been any actual decrease

in the use of the national identity numbers. Yet,

many researchers perceive some uncertainty on

whether they can use national identity numbers

lawfully in their projects. A health register may not

impart non-anonymous patient health data to

research projects unless the recipient can provide

sufficient justification for it.

No matter how favourable the conditions for

health registers may be; legal restrictions prevent

them from being used to their full potential. This

situation induces two parallel debates: The first one

is about the balance between privacy and legitimate

uses of a health register. The second debate is about

the possibility to circumvent patient identification

without sacrificing the benefits of a health register.

1.2 The Origins of Digital Pseudonyms

A pseudonym is, literally, a “false name”. For ages,

pseudonyms have been used by authors and artists,

or even in the rare event of modest researchers, to

disguise their identity. The notion of a digital

pseudonym first appeared in a paper by David

Chaum. He invented digital pseudonyms as a means

to conceal an individual’s real identity in electronic

transactions (Chaum, 1981). The intended field of

application in Chaum’s paper was banking and

electronic commerce. A pseudonym concealed the

identity of the person who actually paid the goods.

In a few consecutive papers, he developed both

the methods and the rationale further. The public key

distribution system provided a secure cryptographic

pseudonym. For the holder of a pseudonym to be

able to communicate or inspect his own personal

data, a trusted third party could manage the

pseudonyms. The rationale was to introduce a new

paradigm for data protection; using technological

means to put the individual in control of his own

data (Chaum, 1984). Organisations would not be

able to share data about the individual without the

data subject “acting out” his consent, so to speak. No

one could collect the complete history of your

transactions, debts or savings. The holder of the

pseudonym would also hold the key to reverse it.

As for the proposed new paradigm of privacy in

banking and electronic commerce, it seems to have

lost completely to the old paradigm of widespread

use of fully identified data subjects. Meanwhile, the

HEALTHINF 2008 - International Conference on Health Informatics

60

fields of health administration and medical research

have revived the idea of digital pseudonyms.

1.3 The Pseudonymisation Process

There are different ways to carry out the process of

generating a digital pseudonym to conceal the data

subject’s real identity.

The simplest form of pseudonyms, used for

decades in research projects based on samples, is to

assign a sequence number to each respondent. To

enhance the respondents’ trust, the researcher could

hire a third party to perform the assigning process.

This method works well for one-time surveys. For a

panel study over time, managing sequence numbers

becomes increasingly more difficult. Coupling data

with relevant data from other sources would require

an overt process of reversing the sequence numbers.

The pseudonyms would be illusory. To exchange a

“real identity” with an unrelated sequence number is

only trustworthy when the researcher grants the

respondent permanent anonymity, without adding to

the data later. It is not a viable method for a long-

term and multi-purpose health register.

A digital pseudonym in a health register involves

advanced cryptography. The input to the algorithm

that generates the pseudonym will have to be a

stable identifying number, which does not change

over time for the same patient. In Norway, the

national identity number provides a convenient

unique input. The health register will not need to

store the national identity number, the algorithm

secures that the same pseudonym is assigned to the

same patient when more data is added to the register.

With a reliable and stable identification, there

are, conceptually, two different ways to generate a

pseudonym. One way is to use an asymmetric hash

function. The encryption algorithm then generates a

digest that is unique to the input, but there is no way

to reverse from the encrypted digest back to the

input identifier. Because the same input identifier

always transforms to the same digest, it is possible

to add data about the same patient in the same health

register. It is, however, not possible to generate data

couplings between individual-level data from two

different health registers. This method provides a

very high degree of confidentiality, but is on the

other hand inflexible. Two health registers cannot be

merged, and it would not be possible to address any

registered patient, for instance if a new treatment

method vital to his particular decease is developed.

The alternative way to generate a pseudonym

resembles the “public key” encryption technology,

and is basically the same as Chaum invented (see

section 1.2 above). The input to the algorithm is the

same stable and reliable patient identity number. An

encryption algorithm, using the “public key” of a

key pair, generates the pseudonym. The same input,

and the same public key, will make it possible to add

data about the same patient to the same health

register. In addition, a decryption algorithm can

reverse the pseudonym back to the “real identity”,

by using the “private key” of the same key pair that

was used for encryption. A trusted third party, which

is an independent pseudonym manager, carry out the

encryption, and if requested, the decryption. The

health register will never see the real identity of the

patient. The trusted third party, who is able to

decrypt the pseudonym, does not have access to any

sensitive information about the patients. This

process provides more flexibility, at the cost of more

fragile pseudonyms. The confidentiality of the

patient is to a higher degree based on trust. Violating

the pseudonyms will be somewhat easier from a

technical point of view.

The latter method, a trusted third party handling

reversible pseudonyms, has been the method of

choice for pseudonymous health registers in Norway

so far. Non-reversible pseudonyms would also

conform to the legislation on health registers, yet it

is not very likely that a register owner voluntarily

would choose this less flexible process.

2 LEGISLATIVE SUPPORT FOR

PSEUDONYMS

Recent technological innovations often seem to be

far ahead of developments in legislation. Society’s

toolbox for protecting values and for distributing

rights and obligations usually adapts slowly, to fit

technological changes that have already taken place.

The introduction of pseudonyms in Norwegian

health registers differs from this typical path of

history. The first Norwegian national register based

on pseudonyms was established in 2004. By that

time participants in various legislation processes had

already advocated this method for more than a

decade. Technologists and professional users of the

registers remained sceptic. Pseudonymous health

registers have not at any rate been “technology-

driven” in Norway, it would be far more correct to

call it a “legislation-driven” development.

Norway has had registers for specific diseases,

such as The Cancer Register, for decades. They

started out as paper files, and were later converted to

computer databases. The specific health registers

ON PSEUDONYMOUS HEALTH REGISTERS - While they Work As Intended, they are Still Controversial in Norway

61

had proved to be useful over time, and the health

authorities started to nourish a desire to establish a

General National Health Register, not to be limited

to any particular diagnosis.

2.1 An Early, Avant-Garde Proposal

Though the advantages of a General National Health

Register were convincing, The Parliament was also

much concerned about the impact on the patients’

privacy. In 1989, they urged The Government to

appoint a committee with a mandate to examine

ways and methods to establish such register “without

threshing individuals’ privacy” (Boe, 1994).

The appointed committee issued a report in 1993

(ONR, 1993). An “Official Norwegian Report” is in

most cases the product of an appointed drafting

committee, at an early stage of the legislation

process. After an official hearing among relevant

stakeholders, both The Government and eventually

The Parliament may make changes to the original

draft, or even turn down the entire proposition all

together.

The drafting committee proposed, in their report,

a new act to provide legal authority to the desired

General National Health Register. The proposed act

was very much ahead of its time. It contained

regulations on cryptographic pseudonyms generated

and managed by trusted third parties, along with a

profound set of rules on ensuring legitimate use of

the register, data quality, and the patients’ right to

access and so on.

However, neither the health authorities nor the

research community was in favour of this avant-

garde way to organise their much-desired new health

register. As the main stakeholders did not support

the proposition, The Government put it on hold, and

it remained so for about eight years.

Instead of either a fully identified register (which

was what the health authorities wanted) or a

pseudonymous health register (the proposition they

turned down), the health authorities established the

Norwegian Patient Register (see section 3.3 below)

in 1997. The Norwegian Patient register was

originally established as a de-identified register (see

section 2.3 below). This was acceptable under the

Personal Data Filing Systems Act of that time, and it

did not require The Parliament to pass any new

legislation.

2.2 Specific Privacy Regulations for

Health Data and Health Registers

The Parliament passed a new general Personal Data

Act on April 14, 2000. The primary motivation for

replacing the old act of 1978 was to comply with the

European Union Directive 95/46/EC, on protection

of personal data.

The Personal Data Act regulates all processing of

personal data, for any legitimate purpose. Therefore,

the rules are quite flexible, leaving most assessments

and decisions to the discretion of the controller. For

the processing of health data, The Parliament did not

consider the general act sufficient. On May 18,

2001, they passed the Personal Health Data Filing

Systems Act, containing rules that are somewhat

more specific. The Personal Health Data Filing

Systems Act too complies with the European Union

Directive, and it has many important features in

common with the general Personal Data Act. For

instance, the information security requirements are

essentially the same.

The primary guiding rule for processing health

data is a requirement to obtain the patients’ consent.

However, the act also recognises a need in some

situations to process data without consent. A typical

exception to requiring consent would be the kind of

health registers where complete coverage is vital to

fulfil the purpose of the register.

2.3 Four Different Levels of Patient

Identification in a Health Register

The key to the regulation of health registers is

section 8 of the Personal Health Data Filing Systems

Act. The initial position is simply that central health

registers are forbidden, unless authorised by this act

or by another statute.

The remainder of section 8 spans the possibilities

and preconditions for establishing health registers,

providing they have an adequate legal authority. The

purpose of a register shall be “to perform functions

pursuant to,” specified health services (the relevant

acts are listed in section 8). Those functions include

“the general management and planning of services,

quality improvement, research and statistics”. In

addition, the Government shall prescribe subordinate

legislation for each health register, defining specific

rules, responsibilities and organisation.

An interesting feature of section 8 is the way it

categorises health registers into four distinct levels

of patient identification. Every health register has to

conform to one of these four levels. The choice of a

HEALTHINF 2008 - International Conference on Health Informatics

62

level of identification encapsulates the privacy

balancing process for each register.

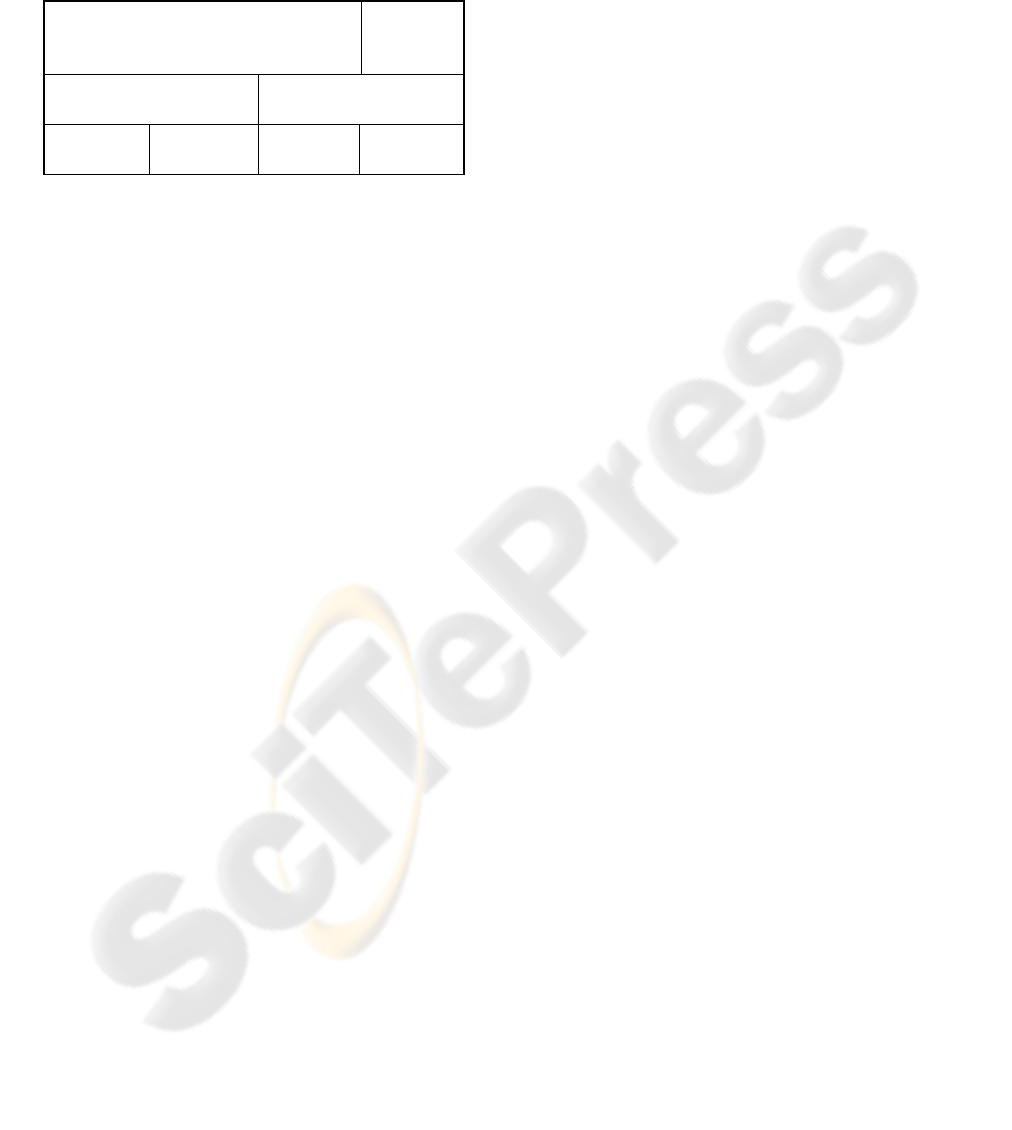

Table 1: Outline of levels of patient identification (adapted

from L’Abée-Lund 2006, page 28).

Personal data (being subject to privacy

regulation)

Not

personal

data

Data refers to unambiguous

individuals

Data may refer to

ambiguous data subjects

Fully

identified

Pseudonyms

De-identi-

fied

Anonymous

The bottom row of the table above shows the four

different levels of patient identification. Their order,

from the left to the right, reflects an order from more

to less strain on the patients’ privacy.

The middle row of the table shows the main

division of whether the data refer to unique patients

or not. Fully identified patients and pseudonymous

patients both have the same granularity. They will

provide the same level of statistical data accuracy.

The top row of the table merely shows that only

three out of the four levels of patient identification

are strictly within the definition of personal data.

Generally, fully identified health registers shall

only process data about patients who consent. The

only exceptions are a moderate number of health

registers particularly named in section 8. By the end

of June 2007 there are exactly nine fully identified

health registers not requiring the patients to consent

(the number of such registers was six by the time the

act was originally passed, in 2001). The Parliament

has to pass a formal change to section 8, specifically

naming the new register, before anyone can establish

a new fully identified central health register with a

complete coverage (i.e. not requiring consent). That

is the beauty of this construct in the Personal Health

Data Filing Systems Act; it ensures an overt and

highly democratic legislation process to be carried

out before establishing a new register.

By using pseudonyms instead of fully identified

patients, the health authorities can establish a new

health register by issuing subordinate legislation.

This means a Parliament decision is not necessary to

establish the register. It also means the register can

omit the patients’ consent, if it needs complete

coverage of the data. The option of pseudonymous

health registers thus entered Norwegian legislation

in 2001, eight years after it was first proposed.

A de-identified and a pseudonymous register

have the same legal status according to section 8.

The health authorities may establish a de-identified

register by issuing subordinate legislation. A de-

identified register means that any clear and manifest

identifying information is removed. The advantage

of a de-identified over a pseudonymous register is

that the de-identified register is technically easier

and less expensive to operate. The paramount

disadvantage of a de-identified register is that the

data is not on a strictly individual level. If a hospital

carries out the same surgical procedure, say four

times, a de-identified register cannot tell whether it

involved four different individual patients or if the

same patient was involved four times.

Pseudonymous and de-identified registers share

the same risk of unlawful re-identification through

computational analysis of the stored data elements

(Malin, 2005). The uniqueness of each registered

individual becomes more transparent as the number

of detailed variables increase. Coping with the risk

of re-identification first requires the register owner

to keep his sobriety on what data is stored and

processed. Second, there is still an indispensable

need for rigid access control and other conventional

information security measures with pseudonymous

and de-identified registers.

In an anonymous register, all information that

can possibly identify individual patients is removed.

In addition to removing the manifest identifiers, the

register also removes, or reclassifies into categories

that are more general, any data suitable for re-

identification by analysis. An anonymous register

takes the granularity of the data into account.

Making the data anonymous often means to take

deliberate action to sacrifice their accuracy.

Anonymous data may be published, and they will

not require extensive data protection. The downside

to anonymous data, which is why they are unapt for

health registers in most cases, is that it is virtually

impossible to add meaningfully to the data.

2.4 The Professionals’ Responsibilities,

and a Democratic Safety Valve

To summarise, the Norwegian legislation allows

four different methods for storing and processing

personal health registers. A method granting more

privacy is less effective for achieving administration

and research goals. This inverse ratio is at the heart

of any privacy regulation. All the four levels of

identification are in use in some existing health

register, and they have all proved to work as

intended. Apart from the likes and the dislikes of

different stakeholders: The four different nominal

levels of identification themselves provide relatively

objective aids for an informed policy debate. We

know what the options are, and how they work. We

ON PSEUDONYMOUS HEALTH REGISTERS - While they Work As Intended, they are Still Controversial in Norway

63

also know how each of these options influence the

privacy of the patients, versus the accuracy of gov-

ernmental decision support data and the possibilities

for providing valuable research data.

The health authorities remain chiefly responsible

for all aspects of the health registers. However, the

very strict preconditions for establishing a fully

identified register (unless requiring patients to

consent) constitute a striking democratic safety

valve. Any such register require The Parliament to

pass a formal change to section 8 of the Health Data

Filing Systems Act. Professional agenda owners and

stakeholders need not, and may not, decide alone on

such privacy invasive registers. Though the process

may be cumbersome and time-consuming, it also

secures a highly democratic participation in the

balancing between privacy and the well-grounded

benefits of a health register.

3 A CURRENT STATUS, AND

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

Up to the end of June 2007, the Ministry of Health

has seriously considered and deliberated on the

option to make a health register pseudonymous on

four different occasions. On two out of these four

occasions, they actually decided to establish the

proposed register with pseudonyms as its level of

patient identification. For the other two registers,

one of them was “promoted” to be a fully identified

register, while the other one was “demoted” to be a

de-identified register.

3.1 The Norwegian Prescription

Database

The first pseudonymous national health register in

Norway is called The Norwegian Prescription

Database (“Reseptregisteret”, in Norwegian). In

October 2003 The Ministry of Health issued the

subordinate legislation providing legal authority for

the register, as required by section 8 of the Health

Data Filing Systems Act. The register was actually

established in the beginning of 2004.

Before the Prescription Database was established,

the medicine statistics were based on sales figures

reported from wholesale dealers. Unquestionably,

the data was insufficient both for straightforward

knowledge about use of medicine, and for research

on effects thereof. Various stakeholders demanded

statistics based on prescriptions and actual dispatch

from pharmacies to individual patients. The intended

purposes were neither to control any patient’s catch

at the pharmacy nor to supervise how named doctors

carried out the business of prescribing. Pseudonyms

both ensure the demanded capacities of the register,

and safeguard against undesirable infringements of

privacy.

All pharmacies report the prescription data

electronically every month. A central data collecting

point transfers the data to a trusted third party. The

trusted pseudonym manager is in this case Statistics

Norway. They transfer the pseudonymous data to the

register owner, which is the Norwegian Institute of

Public Health. Both the patient’s identity (his

national identity number) and the doctor’s identity

(his authorised licence identifier) are replaced with

pseudonyms. The pharmacies are fully identified, on

an enterprise level; their licence identifier is not

pseudonymised (Strøm, 2004).

The Prescription Database was in many ways a

“quiet reform”. The changes have been virtually

invisible to the patients. They still pick up their

prescriptions and carry them to the pharmacies the

same way they did before. They are not asked for

consent. The existence of the Prescription Database

is not a secret in any way, but neither is it of much

concern to the patients. They only know about the

pseudonymous data if they take a particular interest

in detailed level health politics.

3.2 National Statistics Linked to

Individual Needs for Care (IPLOS)

The second pseudonym-based health register is

named the National statistics linked to individual

needs for care (its Norwegian acronym is “IPLOS”,

which is derived from “Individbasert pleie- og

omsorgsstatistikk”). The Ministry of Health issued

the subordinate legislation providing legal authority

for the register in February 2006. The first

mandatory reporting term to the register was

February 2007, collecting data from health care

services throughout all Norwegian municipalities.

The register owner in this case is the Directorate for

Health and Social Affairs. The Tax Administration

is the trusted pseudonym manager, which illustrates

the point that the main feature of a pseudonym

manager is its institutional independence.

Contrary to the Prescription Database, the IPLOS

has not been a “quiet reform”. The information

about individual needs for care was not readily

available from any existing process. Even though the

patients can trust the confidentiality of the central

register, they had to answer a new set of questions.

Someone would type their answers into a local

HEALTHINF 2008 - International Conference on Health Informatics

64

database before they were sent electronically to the

pseudonymous register. The crucial question was not

anymore whether the pseudonym provided sufficient

privacy. Many patients felt offended by some of the

most invasive questions in the form. The forms were

changed as a result from complaints about some of

the questions, such as whether a handicapped patient

needs help after going to the toilet or needs help

with handling the menstrual period.

Pseudonyms only remedy privacy issues that

become present after the patients have left off their

participation. An important lesson is that health

registers mainly deal with data that the patients

hardly are aware of. In many cases, the limits to a

health register are with the processes of eliciting and

collecting data, and not with the confidentiality of

the register itself.

3.3 The Norwegian Patient Register

The Norwegian Patient Register is a hospital and

outpatient clinic discharge register. Data on each

patient is collected from every hospital in Norway.

The acronym NPR is used both in English and in

Norwegian when this register is referred to.

The history of the NPR is complicated, and truly

interesting from a privacy point of view. NPR is the

actual instantiation of the “General National Health

Register” which initiated the committee back in

1989, who proposed a pseudonym-based solution

register in their 1993 report.

After the proposed pseudonymous register was

put on hold, it was revived in 1997 as a de-identified

register. The NPR was established in March 1997. It

receives reports on operative procedures extracted

from the patient administrative systems at all

hospitals. Age, sex, place of residence, hospital and

department, diagnosis, surgical procedure, and dates

of admission and discharge are included in the

register (Bakken et al, 2004). The name and national

ID number of the patients are not included.

The NPR has proved to be a valuable register,

providing much demanded data for both research

and administration purposes. Yet, as a de-identified

register it does have obvious shortcomings. The data

do not refer to strictly unambiguous individuals.

Over the last few years, the health authorities

have made efforts to “promote” the NPR into a fully

identified register. Proponents of privacy argued that

promoting it into a pseudonymous register would be

sufficient for all purposes of the register. The health

authorities and the research community argued that a

pseudonymous register might not provide adequate

data quality. After a heated debate, The Parliament

finally passed the necessary change to section 8 of

the Personal Health Data Filing Systems Act on

February 1, 2007, and included the NPR to be a fully

identified health register. The subordinate legislation

regulating “the new” NPR is expected anytime soon.

3.4 The Abortion Register

The latest example so far, of the Ministry of Health

having seriously considered pseudonyms, is The

Abortion Register. They made a proposition, intent

to establish this as a pseudonymous register. The

proposition went to a formal hearing; the closing

date for the hearing was January 13, 2006. A large

number of the bodies entitled to comment on the

hearing were sceptic to a register containing as

sensitive information as abortions.

The proposal was met with reluctance from

different sides. Many answers to the hearing pointed

out the particular strain on some of the women who

decide to go through an abortion. Induced abortions

are legal in Norway, yet there is a risk of social or

religious condemnation from parts of the society,

making the burden heavier. The Data Inspectorate,

for instance, argued that the knowledge of an

abortion register might influence on actual decisions

on whether to have an abortion or not. Thus the

register could affect, and not merely reflect, the

health care activities. Recently, on June 21, 2007,

The Government decided to make The Abortion

Register de-identified, and not pseudonymous.

The policy debate on The Abortion Register

shows an interesting limit to people’s trust in a

pseudonymous register. The confidentiality is based

on trust in society as we know it today. The

possibility of reversing a pseudonym could be

exploited sometime in the future, when privacy

values may be if worse off.

4 CONCLUSIONS

4.1 Pseudonymous Identities Work

Pseudonyms are a legal and a viable means for

protecting personal data in Norwegian Registers. It

has been one out of four lawful levels of patient

identification since 2001. There are only two health

registers based on pseudonyms so far. The numbers

of both fully identified registers and de-identified

registers are much higher.

A case study on the Prescription Database shows

that the vital functions of a pseudonymous register

work as intended (L’Abée-Lund, 2006). Neither the

ON PSEUDONYMOUS HEALTH REGISTERS - While they Work As Intended, they are Still Controversial in Norway

65

trusted pseudonym manager nor the register owner –

nor anybody else for that matter – gets to see both

the “real” identification numbers and unencrypted

health data relating to the individuals at the same

time. There were initial problems with the data

quality for some time, but more recently, the rate of

errors have been approximately the same as they are

for fully identified registers.

4.2 Pseudonyms are Still Controversial

This brief report on pseudonymous health registers

in Norway reveals some broad categories of arguments

for and against pseudonyms.

The pro arguments are primarily a lower risk of

disclosing information about patients, to people who

do not need it, and for purposes where identification

is unnecessary. A pseudonym increases privacy,

while maintaining the statistical accuracy of the

data.

The contra arguments are increased expenses due

to the third party process, a risk of re-identification

by analysis of the non-identifying data, and a danger

of unforeseeable decrease in privacy if privacy

policies change in the future. Finally, the argument

most often raised against pseudonyms, is the data

quality issue. The register owners will have reduced

opportunities for discovering and fixing errors on

their own. However, the third party may assist in

structured “data laundering”-procedures.

Looking at the pros and cons of pseudonymous

health registers, the amplitude of the controversies

seems somewhat exaggerated. The pseudonymous

registers are plainly an in-between solution. Moving

either one step to the left or one step to the right,

referring to the outline of levels of identifications in

table 1, is merely a change in the balance of the

arguments for and against pseudonyms. Choosing

another level of patient identification will neither

release all the advantages nor solve all the problems

that may occur to a pseudonymous register. A

proposal to make a particular health register

pseudonymous can expect attacks from both sides;

some will say identifying unambiguous individuals

pseudonymously infringes privacy anyway, others

will say pseudonyms place too heavy restrictions on

the register.

In my opinion, though, the fact that the health

authorities have only established two pseudonymous

registers since that option was legislated for in 2001,

while The Parliament has accepted three new fully

identified registers during the same period, sadly

indicates that proponents of pseudonymous registers

in Norway are perhaps fighting a loosing battle.

To the credit of the Personal Health Data Filing

Systems Act, the construct of choosing between only

four lawful levels of identification is in my opinion

both clever and successful. It ensures a broad and

overt democratic process, calling the attention of all

stakeholders to voice their opinion.

REFERENCES

Bakken I J, Nyland K, Halsteinli V, Kvam U H,

Skjeldestad F E. The Norwegian Patient Registry. In

Norwegian Journal of Epidemiology 2004; vol. 14

no. 1, 65-69.

Boe, E., 1994. Pseudo-identities in Health Registers:

Information technology as a vehicle for privacy

protection. In The International Privacy Bulletin 1994;

Vol. 2 no. 3, 8-13.

Chaum, D. L., 1981. Untraceable electronic mail, return

addresses, and digital pseudonyms. Communications

of the ACM 24, 2 (Feb. 1981), 84-90.

Chaum, D., 1984. A New Paradigm for Individuals in the

Information Age; In 1984 IEEE Symposium on

Security and Privacy, IEEE Computer Society Press,

Washington 1984, 99-103.

L’Abée-Lund, Å., 2006. Pseudonymisering av

personopplysninger i sentrale helseregistre [Title

translated: Pseudonymising personal data in central

health registers]. Master thesis, Section for

Information Technology and Administrative Systems,

Faculty of Law, University of Oslo

Malin, B., 2005. Betrayed by My Shadow: Learning Data

Identity via Trail Matching. Journal of Privacy

Technology. 2005; 20050609001. Pittsburg, PA, USA.

ONR 1993. Pseudonyme helseregistre [Title translated:

Pseudonymous Health Registers]. Official Norwegian

Report. NOU 1993:22

Selmer, K., 1992. Hvem er du: Om systemer for

registrering og identifikasjon av personer. [Title

translated: Who are you: On systems for registering

and for identifying individuals] In Lov og Rett, 1992,

311-334

Strøm, H., 2004. Reseptbasert legemiddelregister [Title

tranlated: A prescription-based medicine register].

Norsk Farmaceutisk Tidsskrift. Nr. 1, 2004, 7-9

HEALTHINF 2008 - International Conference on Health Informatics

66