E-LEARNING AS A SOLUTION TO THE TRAINING

PROBLEMS OF SMEs

A Multiple Case Study

Andrée Roy

Faculté d’administration, Université de Moncton, Moncton NB, Canada E1A 3E9, Canada

Louis Raymond

Institut de recherche sur les PME, Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières, Trois-Rivières QC, Canada G9A 5H7, Canada

Keywords: Training, e-learning, learning, workplace learning, SME.

Abstract: Facing pressures from an increasingly competitive business environment, small and medium-sized

enterprises (SMEs) are called upon to implement strategies that are enabled and supported by information

technologies and e-business applications. One of these applications is e-learning, whose aim is to enable the

continuous assimilation of knowledge and skills by managers and employees, and thus support

organisational training and development efforts through the use of Internet technologies. Little is known

however as to the actual role played by e-learning with regard to the training problems faced by SMEs. A

multiple case study of 16 SMEs in the Atlantic region of Canada, including 12 that use e-learning with

varying degrees of intensity, was designed to explore this question. We observed the firms’ training process

in terms of training needs analysis, method selection, tool selection and evaluation, and ascertained how this

process is impacted by their use of e-learning. E-learning is then characterised in terms of opportunity and

feasibility for the development of SMEs and their region.

1 INTRODUCTION

A number of business activities such as

communicating, transacting, environmental

scanning, collaborating with other organisations and

training are now done through the Internet and the

World-Wide-Web, that is, in the form of “e-

business”. Facing pressures from an increasingly

competitive business environment, small and

medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in particular are

called upon to implement strategies that are enabled

by information and communication technologies

(ICTs) and supported by e-business applications

(Brown and Lockett, 2004). One of these

applications is e-learning, whose aim is to enable the

“continuous assimilation of knowledge and skills”

by managers and employees, and thus support

organisational training and development efforts

through the use of Internet technologies (Morrison,

2003, p. 4). But SMEs are organisations that show

specificity in terms of their environment, strategy,

structure, technology and culture, and differ

markedly from large enterprises with regard to their

training and development needs (Vickerstaff, 1992)

and their resources and capabilities (Vinten, 2000)?

Little is known however as to the actual role played

by e-learning with regard to the specific training and

development problems presently faced by SMEs

(Roy and Raymond, 2005). And while e-learning has

been proposed as an opportune and feasible solution

to these problems (Roffe, 2004), there is as of yet

little empirical evidence that this is actually the case.

The aim of this research is to explore this question,

through a multiple case study of 16 SMEs located in

the Atlantic region of Canada.

2 THEORETICAL AND

EMPIRICAL CONTEXT

Research on training in SMEs has been fraught with

conceptual and methodological issues (Wong et al.,

356

Roy A. and Raymond L. (2008).

E-LEARNING AS A SOLUTION TO THE TRAINING PROBLEMS OF SMEs - A Multiple Case Study.

In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies, pages 356-363

DOI: 10.5220/0001514503560363

Copyright

c

SciTePress

1997). In attempting to understand how and why

SMEs succeed or fail with regard to training,

researchers have adopted various theoretical

perspectives such as organisational learning (Gibb,

1997), knowledge management (Kailer and Scheff,

1999), and strategic human resource management

(Keogh, Mulvie and Cooper, 2005). Empirical

research has attempted to identify the factors that

determine the nature, extent and constraints of

workplace learning in SMEs such as firm size,

resources and capabilities (Joyce, McNulty and

Woods, 1995; Carrier, 1999; Fabi, Raymond and

Lacoursière, 2007). As well, the individual,

organisational and socio-economic impacts of

training such as managerial and entrepreneurial

development (Raymond, 1988; Evans and Volery,

2001), organisational performance (Westhead and

Storey, 1996; Patton, Marlow and Hannon, 2000)

and regional development (OECD, 2003) have been

investigated. The main conclusion obtained from the

empirical research to-date is that, in a globalised

knowledge-based economy, there are a number of

unresolved problems that still beset SMEs with

regard to workplace learning, and in particular there

is still great difficulty in providing education and

training that meet the specific needs of SMEs, their

owner-managers and their personnel (Dawe and

Nguyen, 2007).

2.1 Training Problems of SMEs

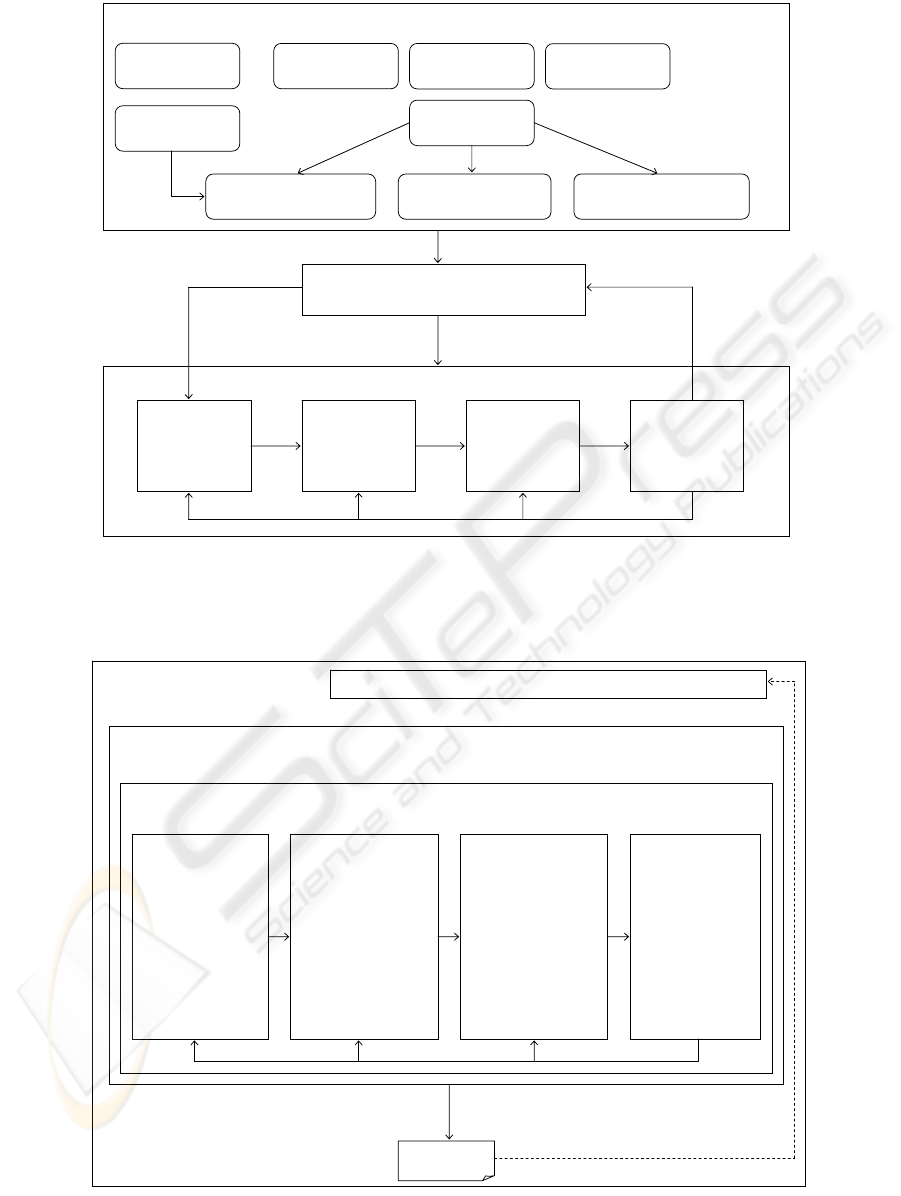

The training problems of SMEs may be

contextualised under three headings, as illustrated in

Figure 1. Problems may first related to the

exogenous and endogenous factors that induce

training needs in SMEs (Meignant, 1997) such as the

pressures from large customers, and strategic

exigencies in terms of product development

(innovation) and market development

(internationalisation). For instance, the supply of

training services offered to SMEs has generally not

been adapted to the specific needs of these firms

(Hogarth-Scott and Jones, 1993). A second set of

problems relates to the way in which the training

function is structured, organised and managed in the

firm (Buckley and Caple, 1990; Kapp, 1999). This is

where organisational size and capabilities often

come into play, as manifested for instance by

insufficient investments in training (Sadler-Smith,

Sargeant and Dawson, 1998). Finally, from an e-

learning perspective, the most important problems

concern the training process itself, that is, the

analysis of training needs, the selection and

application of training methods, the selection and

utilisation of training tools, and the evaluation of

training (Laflamme, 1999). For instance, the

evaluation of training in SMEs is often found to lack

rigour and depth (Jameson, 2000).

2.2 E-learning in SMEs

While one should be cautious in interpreting trend

watching reports (Boon et al., 2005), the adoption of

e-learning technology for purposes of workplace

training and human resource development is rapidly

growing in large organisations, both private and

public, and to a lesser extent in SMEs (Beamish et

al., 2002; Misko et al., 2004). The practitioner

literature, adopting a “best practices” approach for

the most part (Hall and LeCavalier, 2000), has

focused on issues of cost and technological issues,

whereas research on e-learning in the workplace is

deemed to require a better theoretical grounding

(Daelen et al., 2005), a broader conceptualization of

e-learning’s impact on the organisation and its

individual members and, in particular, “a broader

understanding of workers’ learning and affective

needs” (Servage, p. 304). Attempts have thus been

made to identify the contextual conditions,

pedagogical prerequisites, methodologies and design

principles for the successful implementation of e-

learning in SMEs (Tynjälä and Häkkinen, 2005;

Lawless, Allan and O’Dwyer, 2000; Moon et al.,

2005). Through field and action research, other

attempts have been made to implement e-learning

applications designed for SMEs (Swift and

Lawrence, 2003; Mullins et al., 2007), and to

identify the impact of e-learning on the performance

of these organizations (Little, 2001). Overall

however, there is insufficient empirical evidence and

understanding to support the use of e-learning as an

efficient and effective solution to the training

problems of SMEs (Welsh et al., 2003). With a view

to provide such added evidence and understanding,

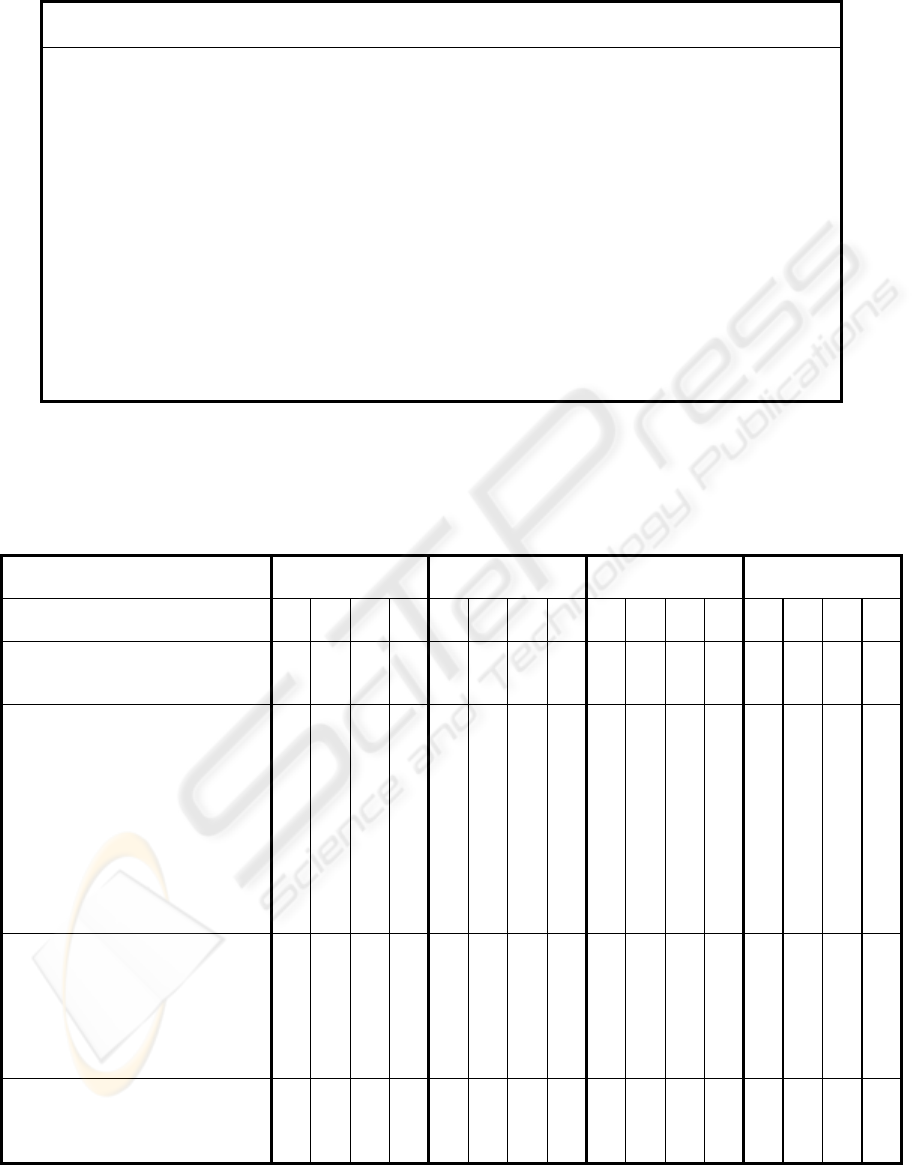

the research model underlying the present study is

presented in Figure 2.

3 RESEARCH METHOD

Given the present state of knowledge on e-learning

in SMEs, a qualitative and exploratory research

approach was used. The case study method is well

adapted in situations where theoretical propositions

are few and field experience is still limited (Yin,

1994). A multiple-site case study allows one to

understand the particular context and evolution of

each firm with regard to e-learning.

E-LEARNING AS A SOLUTION TO THE TRAINING PROBLEMS OF SMEs - A Multiple Case Study

357

Individual and group

expectancies

Social policies

Economic objectives

and projects

Management of the training function

(mission, structure, policies)

Analysis

of training

needs

Selection and

application of

training

methods

Selection and

utilisation of

training

tools

Evaluation of

training

Supply of

training services

External

pressures

Knowledge

management

History

and culture

Present level of

training

Busines

strategy

Training process in SMEs (including e-learning based training)

Factors inductive of training needs in SMEs

Figure 1: Contextualisation of the training problems of SMEs.

Analysis of

training needs

• owner-manager

•employees

• managerial

• operational

• interpersonal

• technical

Selection and

application of

training methods

•affirmative

• interrogative

•active

Selection and

utilisation of

training tools

•visual

•audiovisual

• interactive

Evaluation of

training

•why

•what

•who

•when

• how

Action plan

Training process (including e-learning based training)

Organisation (SME)

Environment of the SME

Regional economic development agency (Atlantic Canada)

Figure 2: Framework for the study of training and e-learning in SMEs.

WEBIST 2008 - International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

358

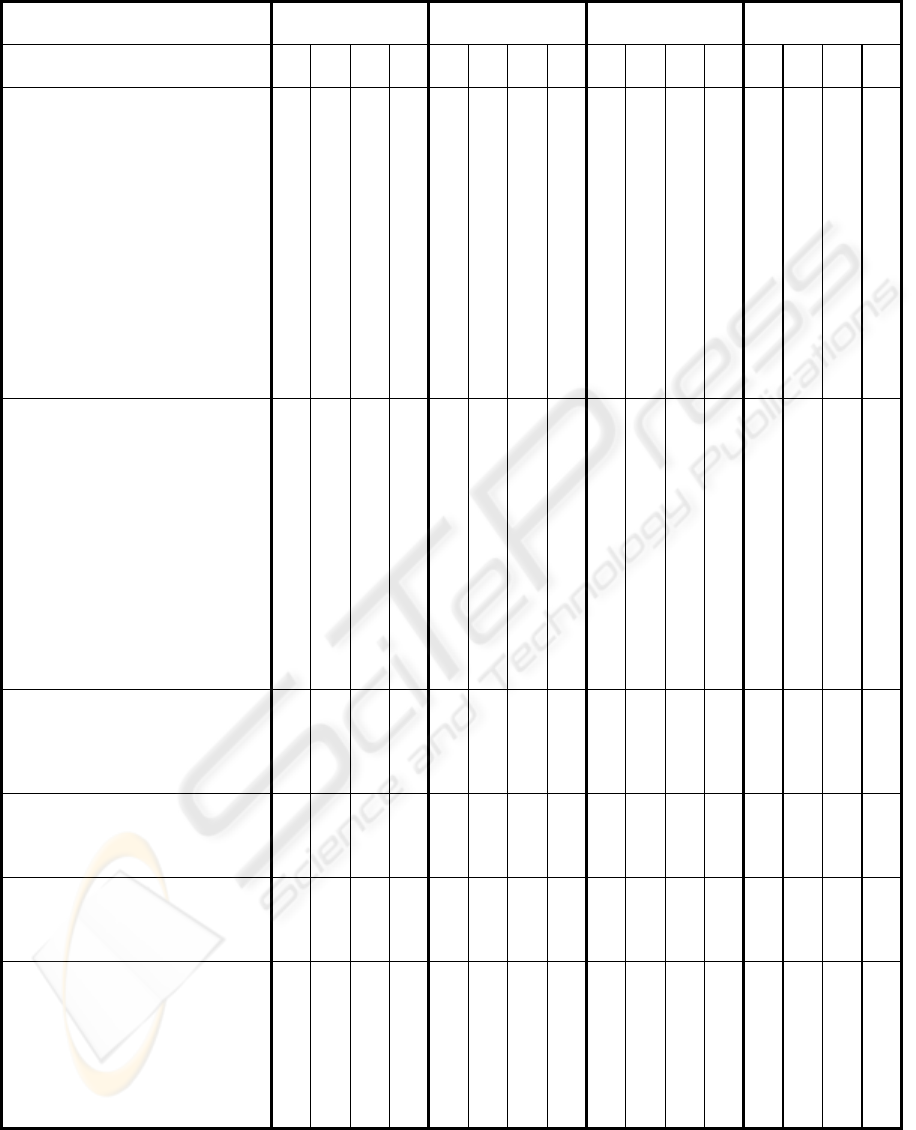

Sixteen SMEs located in the Atlantic region of

Canada were studied, that is, four in each of the

provinces of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince

Edward Island and Newfoundland, selected to be

sufficiently successful (at least 10 years in business)

and representative in terms of industry and size, for

theoretical generalization purposes. Data were

collected through semi-structured tape-recorded

interviews with the owner-manager or CEO and with

the firm’s HR manager or manager responsible for

training. E-learning users were also interviewed in

four cases. Interview transcripts were then coded

and analyzed following Miles and Huberman’s

(1994) prescriptions. As presented in Table 1, these

firms range in size from 60 to 485 employees and

operate in industries whose technological intensity

varies from low to high. All export except for one

firm (M). The SMEs were regrouped in four e-

learning profiles of increasing intensity, based on the

extent of their knowledge and use of e-learning

(none, weak, average, strong).

4 RESULTS

The training provided in the 16 SMEs ranges from

the general/managerial/functional (e.g., accounting)

to the specific/technical (e.g., equipment operation),

including mandatory training (e.g., work safety).

This training is taken both inside and outside the

workplace. Twelve SMEs were found to use e-

learning in support of their training process, in one

form or another. Table 2 characterizes the firms’

training process in relation to their e-learning

profile, noting that there is no obvious relationship

between the SMEs’ size or industry and their use of

e-learning.

In identifying situations of opportunity for the

SMEs, one must first note that e-learning is used to

train owner/managers and office personnel as well as

operations and production personnel. Also, the

perceived advantages obtained from e-learning are

comparable to those found in larger organisations.

The most prevalent e-learning barrier perceived by

strong users relates to cost and financing, whereas

for non users, it is the difficulty in finding online

courses and content that fit their specific needs.

Analysis of training needs - The SMEs’ training

needs center on interpersonal skills and technical

competencies, in addition to that which is mandated

by laws and regulations. These firms are under the

impression that regional development agencies do

not understand their needs and that training support

programs are thus unadjusted. Strong users identify

their training needs with more rigour, in a more

holistic and formal manner, and employ more

sophisticated means to do so, such as a “learning

management system” or LMS (Little, 2002) in the

case of firms C and L. Users identify their training

needs at an earlier stage than non users.

Selection and application of training methods -

The lecture and “learning by doing” methods are

used by all SMEs. When selecting a training

method, the learning style of employees is taken into

greater consideration by users of e-learning. In firms

where this usage is strong, a greater variety of

learning methods are applied.

Selection and utilisation of training tools - SMEs

that have adopted e-learning tend to utilise more

than one type of training tool within a training

course, including visual, audiovisual and interactive

tools. In conjunction with the training methods

selected, this makes the training more adaptable to

the various learning styles and capabilities of

employees.

Evaluation of training - While the “learning by

doing” method of training is the most prevalent, it is

evaluated the least formally. E-learning users

evaluate training more formally and employ more

sophisticated means to do so than non users. Strong

users also evaluate at more than one level, including

the last level in Kirkpatrick’s (1996) evaluation

model, that is, they evaluate not only the learner’s

satisfaction (level 1), the knowledge obtained or

skills achieved (2) and the changes in work

behaviour (3), but also the tangible improvement in

individual and organisational results (4). These firms

also evaluate at more than one moment, that is, not

only after but before and during training.

In evaluating the feasibility of e-learning, the

participants alluded to a number of pre-requisites

that could constitute the core of an action plan to

further enable e-learning in their organisation. The

first such pre-requisite mentioned is the need to

develop an e-learning culture within the

organisation, where owner-managers and employees

are truly motivated and committed to use e-learning

because they believe it is essential to their individual

development and their organisation’s development.

This implies greater awareness and promotion of e-

learning’s value through the dissemination of

knowledge among SMEs as to the nature,

possibilities and advantages of e-learning for

workplace training, and as to the supply and

appropriateness of e-learning services and products

available. This also implies the presence of e-

learning “champions”, that is, credible and

knowledgeable individuals both within (such as key

employees) or outside the firm (such as local or

regional development agencies, trade associations,

business networks and e-learning providers).

E-LEARNING AS A SOLUTION TO THE TRAINING PROBLEMS OF SMEs - A Multiple Case Study

359

Table 1: E-learning profile of the SME cases studied.

SME Year of

creation

Industry Size (no. of

employees)

a

Technological

intensity

b

E-learning

profile

c

A 1971 footwear 150 low-tech weak (III)

B 1909 pulp and paper 280 low-tech average (II)

C 1994 oil and gas 480 medium-low strong (I)

D 1925 pulp and paper 485 low-tech strong (I)

E 1993 computer applications 65 high-tech average (II)

F 1961 corrugated containers 200 low-tech weak (III)

G 1942 peat moss 75 low-tech none (IV)

H 1978 lumber 400 low-tech none (IV)

I 1991 aerospace (components) 200 high-tech weak (III)

J 1964 textile (carpets) 350 low-tech weak (III)

K 1987 automotive (parts) 300 medium-high strong (I)

L 1995 oil and gas 300 medium-low strong (I)

M 1992 computer applications 60 high-tech average (II)

N 1976 pharmaceutical 170 high-tech none (IV)

O 1990 food 220 low-tech average (II)

P 1978 home appliances 70 medium-low none (IV)

a

following North American research (Mittelstaedt, Harben and Ward, 2003; Wolff and Pett, 2000), a small enterprise (SE)

is defined as having 20 to 99 employees, whereas a medium-sized one (ME) has 100 to 499.

b

following the classification of the OECD (2003).

c

regrouping the 16 SMEs into four profiles on the basis of their knowledge and use (depth and breadth) of e-learning

Table 2: Characteristics of the training process in the SMEs studied.

E-learning profile Profile I

(strong)

Profile II

(average)

Profile III

(weak)

Profile IV

(none)

SME

Training process

C D K L B E M O A F I J G H N P

Personnel trained by e-learning

management & office personnel

operation & production personnel

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

Perceived benefits of e-learning

flexibility and accessibility

modularity

rhythm

privacy and autonomy

interactive feedback

cost

learning style

evaluation

distribution of training materials

uniformity

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

Perceived barriers to e-learning

access difficulty (bandwidth)

training and support

courses and content

interaction

learner-related (computer skills)

cost and financing

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

Identification of training needs

holistic

formalisation and rigour

learning management system use

x

+

x

x

+

x

+

x

+

x

+-

x

+

x

+-

+-

+-

-

x

+-

x

+-

-

-

-

-

WEBIST 2008 - International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

360

Table 2 (cont.): Characteristics of the training process in the SMEs studied.

E-learning profile Profile I

(strong)

Profile II

(average)

Profile III

(weak)

Profile IV

(none)

SME

Training process

C D K L B E M O A F I J G H N P

Training methods used

Affirmative methods

lecture

presentations and discussions

conferences and seminars

job rotation

coaching

exercises and applications

Interrogative methods

computer-based training

Active methods

case studies

role playing

simulation and gaming

“learning by doing”

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

Training tools used

Visual tools

blackboard / overhead projector

lecture notes

explicative documents

Audiovisual tools

slide show

film

video tape recorder

Interactive tools

computer

courseware

simulator

multimedia

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

Level of evaluation

1 - reaction (satisfaction)

2 - learning

3 - behaviour

4 - results

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

Who evaluates

trainer

supervisor

manager

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

Moment of evaluation

before training

during training

after training

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

Evaluation tools used

questionnaire

test of knowledge

observation

skill test (equipment)

evaluation report

evaluation checklist

through e-learning

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

E-LEARNING AS A SOLUTION TO THE TRAINING PROBLEMS OF SMEs - A Multiple Case Study

361

A second pre-requisite mentioned by the

respondents is the necessity to lower the present

barriers to the efficient and effective use of e-

learning by SMEs. This implies that employees

possess the computer knowledge and skills required

to use e-learning effectively, and that they be

provided with e-learning software that is user-

friendly and appropriate to the task at hand. This

also implies better management and technical

support of employees with regard to e-learning,

support which was found lacking in a number of

SMEs. This could be done through e-learning

information and decision support tools made

available to SMEs, allowing them for instance to

explore the supply of e-learning products and

services available and find the ones that best fit their

specific training needs. Another barrier that is often

mentioned by SMEs in rural or more remote areas is

the lack of access to high-speed Internet. In this

regard, regional initiatives are being developed to

provide such access to most SMEs, and to their

employees at home, whatever their location.

5 IMPLICATIONS

By empirically confronting the actual use of e-

learning in SMEs with the specific training and

development problems faced by these firms, and

within their training process in particular, this study

has taken a contingent and descriptive mode of

theorising rather than the universalistic (“one best

way”) and prescriptive (“best practices”) one that

has been prevalent to date. Given the intrinsic

limitations of case study research, added

investigation along these lines, both intensive (e.g.,

case studies and action research on e-learning

adoption and implementation) and extensive (e.g.,

surveys of e-learning use, including the service

sector) is needed to further justify and specify the

contingency argument. From a resource-based view,

this could be done by conceptualizing and measuring

the “strategic alignment” of e-learning technology,

and evaluating the performance outcomes of this

alignment.

Owner-managers and HR managers may use the

results of this study to evaluate and compare their

firm’s situation, and thus gain insight with regard to

training and e-learning. Regional development

agencies and other stakeholders may also use these

results to revise and refine their plans and actions to

support the development of SMEs through e-

learning. This technology may yet achieve its

potential if managed and used wisely by SMEs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Atlantic Canada

Opportunities Agency for its support of this

research.

REFERENCES

Beamish, N., Armistead, C., Watkinson, M. and Armfield,

G. (2002), The deployment of e-learning in

UK/European corporate organisations, European

Business Journal, 14 (3), 105-115.

Boon, J., Rusman, E., van der Klink, M. and Tattersall, C.

(2005), Developing a critical view on e-learning trend

reports: trend watching or trend setting?, International

Journal of Training & Development, 9 (3), 205-211.

Brown, D.H. and Lockett, N. (2004), Potential of critical

e-applications for engaging SMEs in e-business: a

provider perspective, European Journal of

Information Systems, 13, 21-34.

Buckley, R. and Caple, J. (1990), The theory and practice

of training, London: Kogan Page.

Carrier, C. (1999), The training and development needs of

owner-manager of small businesses with export

potential, Journal of Small Business Management, 37

(4), 30-41.

Daelen, M., Miyata, C., Op de Beeck, I., Schmitz, P.-E.,

van den Branden, J. and Van Petegem, W. (2005), E-

learning in continuing vocational training,

particularly at the workplace, with emphasis on Small

and Medium Enterprises, Final report (EAC-REP-

003), European Commission.

Dawe, S. and Nguyen, N. (2007), Education and training

that meets the needs of small business: A systematic

review of the research, Adelaide, Australia: National

Centre for Vocational Education Research.

Evans, D. and Volery, T. (2001), Online business

development services for entrepreneurs: an

exploratory study, Entrepreneurship and Regional

Development, 13 (4), 333-350.

Fabi, B., Raymond, L. and Lacoursière, R. (2007), HRM

practice clusters in relation to size and performance:

An empirical investigation in Canadian manufacturing

SMEs, Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship,

20 (1), 25-39.

Gibb, A.A. (1997), Small firms' training and

competitiveness. Building upon the small business as a

learning organisation, International Small Business

Journal, 15 (3), 13-29.

Hall, B. and LeCavalier, J. (2000), E-learning across the

enterprise: the benchmarking study of best practices,

Sunnyvale, California: brandon-hall.com.

Hogarth-Scott, S. and Jones, M.A. (1993), Advice and

training support for the small firms sector in West

Yorkshire, Journal of European Industrial Training,

17 (1), 18-22.

WEBIST 2008 - International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

362

Jameson, S.M. (2000), Recruiting and training in small

firms, Journal of European Industrial Training, 24

(1), 43-50.

Joyce, P., McNulty, T. and Woods, A. (1995), Workforce

training: Are small firms different? Journal of

European Industrial Training, 19 (5), 19-25.

Kailer, N. and Scheff, J. (1999), Knowledge management

as a service: Co-operation between small and medium-

sized enterprises (SMEs) and training, consulting and

research institutions, Journal of European Industrial

Training, 23 (7), 319-328.

Kapp, K.M. (1999), Moving training to the strategic level

with learning requirements planning, National

Productivity Review, 18 (2), 15-21.

Keogh, W., Mulvie, A. and Cooper, S. (2005), The

identification and application of knowledge capital

within small firms, Journal of Small Business and

Enterprise Development, 12 (1), 76-91.

Kirkpatrick, D. (1996), Great ideas revisited: Techniques

for evaluating training programs, Training &

Development, 50 (1), 54-59.

Laflamme, R. (1999), La formation en enterprise:

nécessité ou contrainte?, Québec : Presses de

l’Université Laval.

Lawless, N., Allan, J. and O’Dwyer, M. (2000), Face-to-

face or distance training: Two different approaches to

motivate SMEs to learn, Education & Training, 42

(4/5), 308-316.

Little, B. (2001), Achieving high performance through e-

learning, Industrial and Commercial Training, 33

(6/7), 203-207.

Little, B. (2002), Harnessing learning technology to

succeed in business, Industrial and Commercial

Training, 34 (2), 76-79.

Meignant, A. (1997), Manager la formation, Paris:

Editions Liaisons.

Miles, M.B. and Huberman, A.M. (1994), Qualitative

Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook, 2

nd

Edition,

Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications.

Misko, J., Choi, J., Hong, S.Y. and Lee, I.S. (2004), E-

learning in Australia and Korea: Learning from

practice, Seoul: Korea Research Institute for

Vocational Education & Training.

Mittelstaedt, J.D., Harben, G.N. and Ward, W.A. (2003),

How small is too small? Firm size as a barrier to

exporting from the United States, Journal of Small

Business Management, 41 (1), 68-84.

Moon, S., Birchall, D., Williams, S. and Vrasidas, C.

(2005), Developing design principles for an e-learning

programme for SME managers to support accelerated

learning at the workplace, Journal of Workplace

Learning, 17 (5/6), 370-384.

Morrison, D. (2003), E-learning strategies: how to get

implementation and delivery right first time,

Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons

Mullins, R., Duan, Y., Hamblin, D., Burrell, P., Jin, H.,

Jerzy, G., Ewa, Z., and Aleksander, B. (2007), A Web

based intelligent training system for SMEs, Electronic

Journal of e-Learning, 5 (1), 39-48.

OECD (2003), OECD science, technology and industry

scoreboard 2003: Towards a knowledge-based

economy, http://www1.oecd.org/publications/e-

book/92-2003-04-1-7294/D.9.1.htm.

Patton, D., Marlow, S. and Hannon, P. (2000), The

relationship between training and small firm

performance: Research frameworks and lost quests,

International Small Business Journal, 19 (1), 11-27.

Raymond, L. (1988), The impact of computer training on

the attitudes and usage behavior of small business

managers, Journal of Small Business Management, 26

(3), 8-13.

Roffe, I. (2004), E-learning for SMEs: Competition and

dimensions of perceived value, Journal of European

Industrial Training, 28 (5), 440-455.

Roy, A. and Raymond, L. (2005), E-learning in support of

SMEs: pipe dream or reality?, Proceedings of the 4

th

European Conference on e-Learning, Royal

Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences,

Amsterdam, 383-388.

Sadler-Smith, E., Sargeant, A. and Dawson, A. (1998),

Higher level skills training and SMEs, International

Small Business Journal, 16 (2), 84-94.

Servage, L. (2005), Strategizing for workplace e-learning:

Some critical considerations, Journal of Workplace

Learning, 17 (5/6), 304-317.

Swift, J. and Lawrence, K. (2003), Business culture in

Latin America: interactive learning for UK SMEs,

Journal of European Industrial Training, 27 (8), 389-

397.

Tynjälä, P. and Häkkinen, P. (2005), E-learning at work:

theoretical underpinnings and theoretical challenges,

Journal of Workplace Learning, 17 (5/6), 318-336.

Vickerstaff, S. (1992), The training needs of small firms,

Human Resource Management Journal, 2 (3), 1-15.

Vinten, G. (2000), Training in small-and medium-sized

enterprises, Industrial and Commercial Training, 32

(1), 9-14.

Welsh, E., Wanberg, C., Brown, K. and Simmering, M.

(2003), E-learning: Emerging uses, empirical results

and future directions, International Journal of

Training and Development, 7 (4), 245-258.

Westhead, P. and Storey, D. (1996), Management training

and small firm performance: Why is the link so weak?

International Small Business Journal, 14 (4), 13-24.

Wolff, J.A. and Pett, T.L. (2000), Internationalization of

small firms: An examination of export competitive

patterns, firm size, and export performance, Journal of

Small Business Management, 38 (2), 34-47.

Wong, C., Marshall, J.N., Alderman, N. and Thwaites, A.

(1997), Management training in small and medium-

sized enterprises: Methodological and conceptual

issues, International Journal of Human Resource

Management, 8 (1), 44-65.

Yin, R.K. (1994), Case study research: Design and

methods, 2

nd

Edition, Thousand Oaks, California: Sage

Publications.

E-LEARNING AS A SOLUTION TO THE TRAINING PROBLEMS OF SMEs - A Multiple Case Study

363