ASSESSING THE PROGRESS OF IMPLEMENTING

WEB ACCESSIBILITY

An Irish Case Study

Vivienne Trulock

Ilikecake Limited, 12 Lealand Road, Clondalkin, Dublin 22, Ireland

Richard Hetherington

Centre for Interaction Design, School of Computing, Napier University, 10 Colinton Road, Edinburgh EH10 5DT, U.K.

Keywords: Web Accessibility, WCAG Guidelines 1.0, automated testing, manual testing, partial accessibility.

Abstract: In this paper we attempt to gauge the implementation of web accessibility guidelines in a range of Irish

websites by undertaking a follow-up study in 2005 to one conducted by McMullin three years earlier

(McMullin, 2002). Automatic testing against version 1.0 of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines

(WCAG 1.0) using WebXact online revealed that accessibility levels had increased among the 152 sites

sampled over the three-year period. Compliancy levels of A, AA and AAA had risen from the 2002 levels

of 6.3%, 0% and 0% respectively to 36.2%, 8.6% and 3.3% in 2005. However, manual checks on the same

sites indicated that the actual compliance levels for 2005 were 1.3%, 0% and 0% for A, AA and AAA. Of

the sites claiming accessibility, either by displaying a W3C or ‘Bobby’ compliance logo, or in text on their

accessibility statement page, 60% claimed a higher level than the automatic testing results indicated. When

these sites were further manually checked it was found that all of them claimed a higher level of

accessibility compliance than was actually the case. As most sites in the sample were not compliant with the

WCAG 1.0 for the entire set of disabilities, the concept of ‘partial accessibility’ was examined by

identifying those websites that complied with subsets of the guidelines particular to different disabilities.

Some disability types fared worse than others. In particular blindness, mobility impairment and cognitive

impairment each had full support from at most 1% of the websites in the study. Other disabilities were better

supported, including partially-sighted, deaf and hearing impaired, and colour blind, where compliance was

found in 11%, 23% and 32% of the websites, respectively.

1 INTRODUCTION

The importance of access to the World Wide Web

cannot be underestimated. This is particularly so for

those individuals who are disabled in such a way as

to render access to traditional media difficult to

attain or to use effectively. Within the last decade,

many countries have begun to implement a legal

requirement for websites to be accessible. Often this

has been the result of general disability or equality

legislation, rather than legislation directed

specifically at online access. In Ireland for example,

Part 1 Section 4(1) of the Equal Status Act, Ireland,

2000 states that a failure to do all that is reasonable

to provide a service to a person with a disability is

deemed an act of discrimination (Irish Government,

2000). The Employment Equality Act of Ireland,

1998, Section 16(3) (Irish Government, 1998) has a

similar definition. Whilst The Disability Act,

Ireland, 2005 states in section 27(1) that the head of

the organisation is responsible for ensuring that

services are available to people with disabilities

(Irish Government, 2005). A website then, if

regarded as a service, must be as available to a

disabled person as it is to an able bodied person

otherwise the service is discriminatory. Available

redress includes compensation and an order that the

problem(s) be fixed or removed (Irish Government,

2000). At present, no cases regarding website access

have been pursued under these Acts.

The European Union, of which Ireland is a

member, has been proactive in developing explicit

105

Trulock V. and Hetherington R. (2008).

ASSESSING THE PROGRESS OF IMPLEMENTING WEB ACCESSIBILITY - An Irish Case Study.

In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems - HCI, pages 105-111

DOI: 10.5220/0001667001050111

Copyright

c

SciTePress

web accessibility guidelines. The eEurope 2002

Action Plan states that the content of public sector

web sites in Member States and in European

Institutions must be designed to be accessible to

ensure that citizens with disabilities can access

information and take full advantage of the potential

for e-government (European Commission &

Council, 2000). The timeframe for adoption of the

Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) guidelines by

public websites was designated to be the end of

2001. A separate communication from the EU,

‘eEurope 2002: Accessibility of Public Web Sites

and their Content’, recognised the WAI WCAG 1.0

guidelines to be the ‘global de facto Web

accessibility standard’ and concluded that both

public and private websites should be encouraged to

achieve accessibility during 2003, the European

Year of Disabled People (European Commission,

2001).

Considering the significant introduction of

legislation addressing online accessibility, either

directly or indirectly, over the last 10 years, an

investigation of the impact of legislation and

associated guidelines on the accessibility of web

sites appears timely, in order to assess just how

much, or how little progress is being made.

However, in order to establish where we are in terms

of accessibility, we need to know where we’ve been.

In the Irish context we are fortunate in having access

to a study that determined the accessibility of a

sample of Irish web sites in 2002 (McMullin, 2002).

Using these data as the baseline, a follow-up study

on the same sites was undertaken to re-assess their

accessibility and compliance levels to WCAG 1.0 in

2005. In this paper we report our major findings.

2 METHODOLOGY

2.1 Guidelines

Websites were assessed for accessibility using

WCAG version 1.0 (W3C, 1999). These guidelines

are an ‘indicator of web accessibility’ (McMullin,

2002) and consist of 14 separate guidelines and 65

specific checkpoints, which are broken into 3 levels

of priority: priority 1, 2 & 3. Priority 1 guidelines

must be met in order to afford basic accessibility.

Priority 2 guidelines should be met to offer

additional access to a broader range of disabled

groups. Priority 3 guidelines may be met to provide

further additional support (Brewer, 2004; McMullin,

2002; Williams & Rattray, 2003; Sullivan &

Matson, 2000; Hackett, Parmanto & Zeng, 2004).

There are 3 levels of compliance with the

WCAG 1.0 guidelines: A, AA and AAA. The

compliance level of A means that all priority 1

guidelines are satisfied. The compliance level of AA

means that all priority 1 and 2 guidelines are

satisfied. AA is considered to be ‘professional

standard’. The compliance level of AAA means that

all priority 1, 2 and 3 guidelines are satisfied. AAA

is considered to be ‘gold standard’ (Brewer, 2004;

McMullin, 2002; Loiacono & McCoy, 2004;

Hackett, et al, 2004). Note that in order for a site to

be truly compliant to any particular level it must

satisfy all the checkpoints to that level, not simply

those which can be verified by accessibility

verification software.

2.2 Accessibility Testing

The 159 site URLs from McMullin’s 2002 study

(McMullin, 2002) were used to retrieve websites for

testing and analysis. Of these, three websites had

placeholder pages and four sites were not available

as the URL had not been renewed. Consequently,

the total number of websites analysed in the current

study was 152. Of these, 101 sites had the original

URL used in the 2002 study, 40 had an automatic

redirect to an updated URL and one had a non-

automatic, linked redirect. A further 10 had URLs

which were replaced by manual searches in Google,

WHOIS and the Enterprise Ireland website. The

sample tested represented a considerable range of

websites including those belonging to the military,

political parties and charities, national and local

governments, and public and private commercial

sites ranging from large multinationals to smaller

local companies.

In the present study, the home or index page was

checked in greatest detail. The home page is

generally the point at which most users access a web

site. Therefore, if a home page is inaccessible, there

may be no way for a disabled user to access the rest

of the site (Sullivan & Matson, 2000). In addition,

the home page of a web site tends to be the page that

is the best planned and coordinated, unlike lower-

level content pages which can be managed by

different departments or individuals. Therefore, it is

likely that if any web pages are accessible, the home

page is. (Lazar, Beere, Greenidge & Nagappa,

2003). Moreover, the entry page can be taken as a

good signifier of a web site’s overall accessibility

level (Williams & Rattray, 2003). However, in order

to ascertain a true measure of compliance, manual

and automatic checks were performed on the other

pages of a website. As some manual checks cannot

ICEIS 2008 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

106

reasonably be performed without user simulation,

this was included where appropriate in the testing.

Some of the sites in this study used framesets or

iframes as part of their design. As the automatic

validator only analyzes the URL submitted and not

the embedded frame pages, these were analyzed

separately. Therefore a page using frames is deemed

to have an accessibility rating equal to that of the

frameset plus that of each of the pages viewed in the

frameset on page load. Pages using iframes also had

the accessibility results of the iframe page added to

the original page.

The WebXact validator available at

http://webxact.watchfire.com/ was chosen as the

automated testing tool. The 2002 study used Bobby,

however WebXact replaced Bobby on-line just prior

to this study and the Bobby URL

(http://bobby.watchfire.com/) redirected to

WebXact.

Initial analysis concentrated on the automatically

verifiable checkpoints allowing for a direct

comparison to be made between the 2002 and the

2005 results. Checkpoints not failing the automated

test were recorded as passing the validation. Where

appropriate (e.g. when directed by the automatic

testing tool), manual checks were undertaken and an

additional analysis carried out. In the cases where

checkpoints validated both manually and

automatically, the checkpoint was considered to

have been passed. A checkpoint was deemed to have

been failed if either manual or automatic testing

revealed a failure.

The complete method for performing manual

checks of web pages has been described (Trulock,

2006) and involved the use of additional software

tools to validate specific checkpoints: The JAWS

6.20 screen reader was used to determine if

accessible text versions or alternative text

descriptions where applied to any time-based

multimedia present on web pages (checkpoint 1.4).

Colour contrast between foreground and background

(checkpoint 2.2) was checked using an accessibility

tool called ‘aDesigner’ (Takagi, Asakawa, Fukuda &

Maeda, 2004). The default settings were used, which

simulated a crystalline lens transparency of 40 years

old, in addition to 3 types of colour blindness. Web

pages had to pass all 4 conditions to achieve

validation.

Compliance of documents with formal grammar

specifications (checkpoint 3.2) was checked at

http://validator.w3.org/ for html and xhtml.

Cascading Style Sheets (CSS ) were validated at

http://jigsaw.w3.org/css-validator/validator-uri

(CSS1, CSS2). Where xhtml files fail the check and

the associated CSS files cannot be assessed, the CSS

file was tested separately at http://jigsaw.w3.org/css-

validator/ using the ‘validate by file upload’ option.

Pages which failed any applicable test were deemed

to have failed the check. Browser settings were

adjusted in order to test whether documents could be

read without style sheets (checkpoint 5.2) and also to

ensure that pages were usable when scripts, applets

or other programmatic objects were turned off

(checkpoints 6.1 and 6.3).

A flickering check tool available at

http://www.webaccessibile.org/test/check.aspx was

used to check for flickering animated gifs, which are

covered by checkpoint 7.1. Flickering elements

outside the critical range (4-59 flashes/second) were

deemed to have passed (W3C, 1999).

In order to assess the readability of text, a testing

tool available from Juicy Studios was used

(http://juicystudio.com/services/readability.php).

Pages that obtained a Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level of

5

th

Grade (5.x) or lower where considered to have

satisfied the related checkpoint (checkpoint 14.1).

Finally, the correct linearisation of tables

(checkpoint 5.3) was checked by viewing with the

Lynx text-only viewer (http://lynx.isc.org/current/).

Lynx treats the <tr> tag as a <br> tag, and the <tr>

and <td> tags as spaces, effectively linearising a

table.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Comparison of 2002 and 2005

Accessibility Levels

In 2002, an accessibility study of 159 Irish websites

revealed that around 6 percent of websites checked

were accessible to the minimum level of

accessibility, level A (McMullin, 2002). The study

only checked automatically verifiable checkpoints

and no sites were compliant to Level AA, or Level

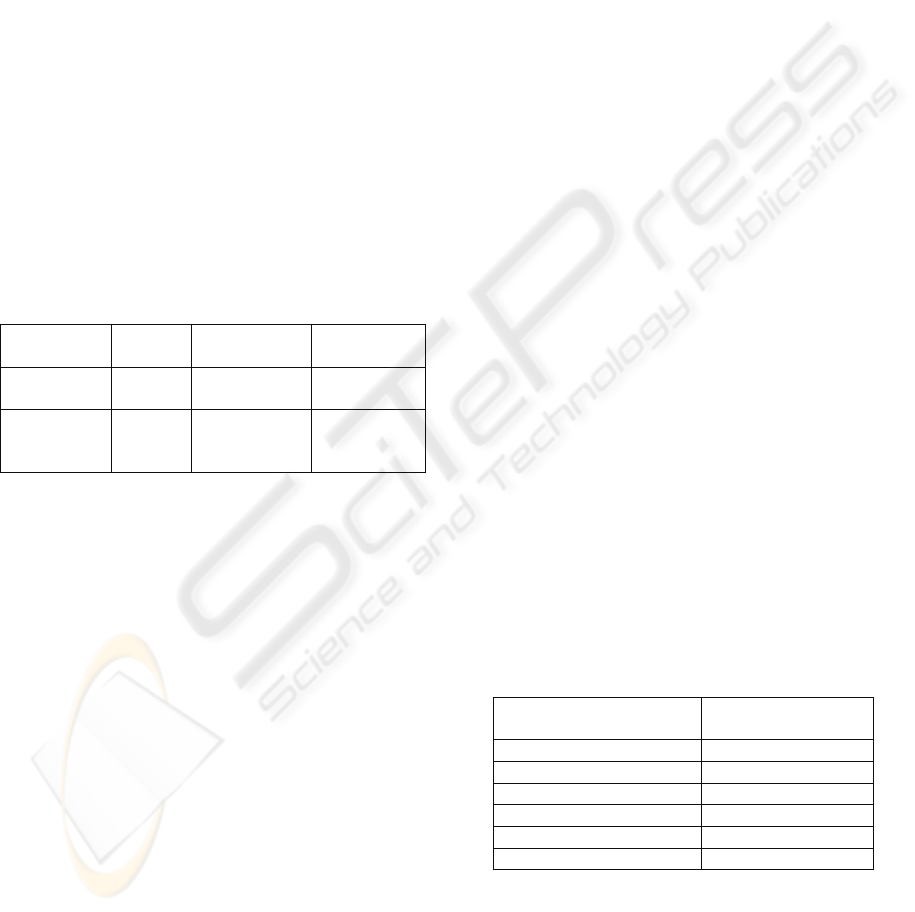

AAA. Table 1 shows the level of compliance of 152

of these sites tested in 2005 using both automated

checking and a combination of automated and

manual checking. Comparing sites using automatic

validation only, indicates that there has been an

almost 6-fold increase in sites achieving Level A

compliance over the three year period with around

36% of those sites tested now achieving a basic level

of accessibility. This suggests that there has been an

increase in awareness of accessibility issues and at

least some attempt to implement a degree of

accessibility over this time. In addition, the

proportion of websites achieving higher levels of

ASSESSING THE PROGRESS OF IMPLEMENTING WEB ACCESSIBILITY - An Irish Case Study

107

accessibility compliance also increased from 0 in

2002 (McMullin, 2002) to 8.6% and 3.3% for levels

AA and AAA respectively.

While the levels of accessibility of sites in 2005

were dramatically increased compared to their 2002

levels as determined by automatic checking a

different picture emerged when accessibility was

determined by automatic checking supplemented by

manual checking (Table 1). In fact, the trends

previously noted over the three-year period were just

the opposite. Only 1.3% of websites achieved

compliance at level A equating to 2 sites out of the

152 checked in 2005. No site reached full

compliance for Levels AA and AAA. This result

may imply that while web designers are aware of

web accessibility they are only ensuring validation

of the automatically checked checkpoints and appear

to be ignoring those checkpoints that can only be

satisfied through additional manual testing.

Table 1: Percentages of a sample of 152 Irish websites

found to be accessible in 2005 according to WCAG 1.0

Compliance Levels. Accessibility was determined using

both automated and manual testing.

3.2 Accessibility Claims

In the current study, 20 websites claimed to be

compliant to the WCAG 1.0 guidelines either by

displaying a W3C or ‘Bobby’ compliance logo, or in

text on their accessibility statement page. By

automatic checking alone, seven sites were

compliant to the level claimed, 12 sites claimed a

higher compliance level than their test results

indicated, and one site claimed a lower compliance

level. A further 35 sites were compliant to the

automatic checks at varying levels but no claim of

that compliance could be found on their sites. When

a combination of automatic and manual checking

was carried out, all 20 sites were found to have

claimed a higher level of accessibility than the test

results indicated. Two sites were identified as being

fully compliant to level A, however, one site did not

claim any compliance level and the other site

claimed compliance of AA.

3.3 “Partial Accessibility” Levels

Most sites in our sample of websites failed to

achieve even basic compliance of WCAG 1.0.

However, it is possible that websites may be fully

accessible to certain disability groups even though

they are not fully compliant. This concept of ‘partial

accessibility’ can be assessed by analysing which

websites comply with particular subsets of guideline

checkpoints. Six disabilities were identified for

analysis: fully blind, partially sighted, colour blind,

deaf & hearing impaired, mobility impaired and

cognitively impaired. What follows is a general

overview of those checkpoints identified as relevant

to a specific disability. The sets of checkpoints for

each category of disability were evaluated by a

combination of both automated and manual

checking as described previously. A complete list of

all checkpoints identified as relevant to each of the

six disabilities can be found in Trulock, 2006.

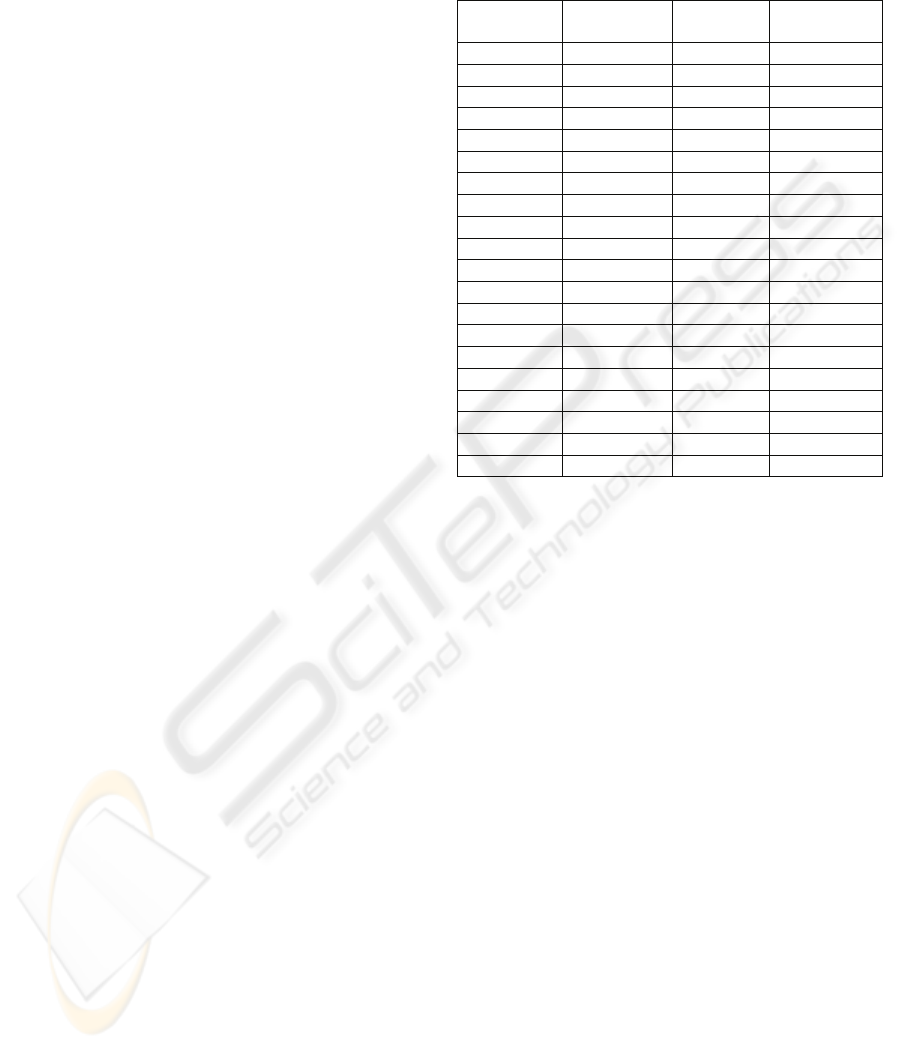

Of the 65 possible checkpoints, 55 were

identified as being relevant to blind individuals.

These included text equivalents, appropriate mark

up, valid documents, table formatting, device

independence and skip links. When these

checkpoints were examined, no site passed all of

these checkpoints (Table 2).

Six checkpoints were identified for partially

sighted users which included text equivalents, good

contrast, use of style sheets, use of relative units, and

lack of movement on pages. Seventeen sites (11%)

complied with these 6 checkpoints (Table 2).

Four checkpoints were examined which were

considered to be relevant to colour blind individuals.

These include non-colour formatting, colour contrast

and use of style sheets. 48 sites (32%) were found to

be compliant with these 4 checkpoints (Table 2).

Table 2: Number of websites found accessible to specific

disabilities for a sample of 152 Irish Websites.

Disability No. of websites

accessible

Blind 0

Partially-sighted 17

Colour blind 48

Deaf 35

Mobility impaired 2

Cognitively impaired 0

Deaf and hearing impairment were combined as they

both require similar treatments in terms of accessible

design. Four checkpoints were identified as being

relevant to deaf and hearing-impaired individuals,

including use of captions, dynamic content

equivalents, and clear and simple language. 35 sites

Testing

Method

WCAG

Level A

WCAG

Level AA

WCAG

Level AAA

Automatic

Check Only

36.2% 8.6% 3.3%

Automatic

and Manual

Check

1.3% 0% 0%

ICEIS 2008 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

108

(23%) complied with these 4 checkpoints (Table 2).

It should also be noted that most sites checked did

not have any specific audio or video content. Clear

and simple language is regarded as an important

checkpoint because deaf individuals are likely to

have lower reading levels due to unfamiliarity with

the language (Gallaudet Research Institue, 2003).

Checkpoints relating to the mobility impaired

numbered 12 and these related to issues including

use of relative units, device independence,

avoidance of movement, skip links, labels, and

sitemaps. Only 2 sites (1%) of the sample were

compliant with all of these checks (Table 2).

Twenty-two checkpoints relating to cognitive

impairment were identified, including text

equivalents and supplements, document and

navigation structure, no flickering, blinking or

moving content, language levels, link targets and

alternative search functions. No sites in the sample

complied with all of these checkpoints (Table 2).

3.4 Checkpoint Compliance

As WCAG 1.0 checkpoint failure rates for

automatically verifiable checkpoints were published

in the 2002 study ((McMullin, 2002)), a direct

comparison of these specific checkpoints can be

made with the data obtained in this study. Overall,

14 checkpoints were complied with more often and

6 checkpoints less often in 2005 (Table 3).

Of the 14 checkpoints that were complied with

more often, there was a striking improvement of

around 20-30% of more sites complying for five.

These checkpoints related to: providing a text

equivalent for every non-text element (1.1),

identifying the primary natural language of the

document (4.3), ensuring that equivalents for

dynamic content are updated when the dynamic

content changes (6.2), titling each frame to facilitate

frame identification and navigation where framesets

are used (12.1) and associating labels explicitly with

their controls (12.4). Of the six checkpoints showing

a relative reduction in compliance over the three-

year period, five were considered relatively minor

having a reduction of around 4% of sites surveyed or

less over the three-year study period. However, for

checkpoint 1.5 a reduction in compliance of around

11% was observed (Table 3). This checkpoint relates

to client-side image maps requiring alternative text

links on them.

Table 3: Percentages of a sample of Irish websites failing

to comply with automatically verifiable WCAG 1.0

checkpoints in 2002 and 2005. The 2002 data were

obtained from McMullin, 2002.

WCAG 1.0

Checkpoint

%Failure

2002

%Failure

2005

Difference

1.1 91.6 62 +29.6

12.1 34.0 10 +24.0

6.2 33.3 2 +31.3

3.4 98.7 81 +17.7

3.2 89.9 94 -4.1

13.1 76.7 80 -3.3

12.4 69.8 47 +22.8

9.3 69.2 55 +14.2

13.2 12.6 4 +8.6

3.5 6.3 16 -9.7

7.4 3.8 1 +2.8

6.5 3.8 1 +2.8

7.5 2.5 0 +2.5

7.3 1.9 2 -0.1

7.2 1.3 3 -1.7

5.5 97.5 84 +13.5

4.3 96.2 72 +24.2

10.5 89.9 77 +12.9

10.4 61.6 43 +18.6

1.5 1.9 13 -11.1

4 CONCLUSIONS

Achieving accessibility to any level is not an easy

task. It requires, on the part of the developer:

awareness, education, training, organisation,

diligence, perseverance, communication and

persistence. For the organisations involved it

requires time, money, interest, understanding and

compromise. For the countries involved it requires

public awareness funding, legal consequences for

inaction and the belief that disabled individuals have

rights to information equal to that of other citizens.

While there has been an increase in accessibility

levels and awareness of the issue much still needs to

be done. The results from this study suggest some

effort has been made to achieve a basic level of

accessibility compliance as determined by

automated checking. Indeed it can be argued that the

availability of automated testing tools has made the

greatest contribution to the improvement in

accessibility levels of the websites sampled.

However, such tools have their limitations (Trulock,

2006), and a combination of automated and manual

checking, and conducting an evaluation of partial

accessibility for specific disabilities revealed that

sadly, the majority of sites examined in this study

are still excluding many users.

ASSESSING THE PROGRESS OF IMPLEMENTING WEB ACCESSIBILITY - An Irish Case Study

109

There are several iterative steps involved in

implementing online accessibility under the current

guidelines. First of all, there needs to be an

awareness of the accessibility issue, in that there is

an issue. Education of web developers and

promotion of accessibility issues will raise the

profile of the accessibility movement. This should

include the updating of all web modules currently

taught in colleges and universities to include

accessibility issues. In addition, public awareness of

accessibility and equality mandates and laws should

also increase the likelihood that a client will request

an accessible website during the initial consultation

phase. This can be accomplished through general

advertising in the media, or delivered during

seminars to public interest groups.

Web developers need to understand how to

actually implement a site that conforms to their

relevant guidelines whether they are Section 508

(USA), WCAG 1.0 (EU and Australia) or the

Common Look and Feel Guidelines (Canada). In

many countries WCAG 1.0 has been widely

regarded as the standard for web accessibility. The

release of WCAG 2.0 is imminent, and promises a

series of guidelines and principles, which will be

more precisely testable and more relevant to the

advanced technologies now found on the web (W3C,

2008). It will be interesting to monitor the effect of

WCAG 2.0 on levels of web accessibility.

Considering the wide range of expertise

possessed by individuals tasked with authoring web

pages, implementing an accessible web site is far

from trivial. Additional training on the part of the

developer may be required, which could be self-

directed or formalised in seminars, and should

include both understanding of web accessibility

issues and specific practical skills development on

how these guidelines should be implemented. One

third of the sites surveyed here were at least partially

compliant, but more should be done regarding

raising education levels of designers.

Websites should be created with accessibility

standards in mind. An accessibility statement should

be created as part of the design guidelines to ensure

that standards are adhered to both during the initial

design phase and during subsequent site updates.

This statement should include the level of

accessibility to which the site is being designed. The

site should then be tested for conformity to the

guidelines. Several automatic checking systems are

available. These are a good place to start, however,

all the manual checks should also be checked and

passed by the designer. This can be difficult as some

guidelines can easily be misinterpreted. In response

to this situation, a resource website, hosted at

http://www.accessibleireland.net has been created by

the first author in an attempt to clarify and elaborate

upon some of these issues. Also, it may help

developers to join a mailing list or network of like

minded individuals. In Europe/Ireland organizations

include: IRL-DeAN (Irish Design-for-all

eAccessibility Network), E-DeAN (European

Design for All e-Accessibility Network), IDD

(Institute for Design & Disability), EIDD (European

Institute for Design & Disability) and GAWDS

(Guild of Accessible Web Designers).

Websites should also be retested regularly for

compliance. In some cases, changes made to the site

can themselves be non-compliant making it

necessary to retest the site after changes are made.

Ideally, the site should be evaluated by actual users,

both disabled and otherwise, on a variety of

platforms, systems, resolutions, text sizes and colour

availability. This is necessary to ensure that the site

is actually usable. A study by the Disability Rights

Commission claimed that up to 45% of the problems

experienced by disabled users were not a violation

of any WGAC 1.0 Checkpoint, and would not have

been detected without user testing (Disability Rights

Commission, 2004). Again, changes made may

cause further confusion to other groups of users, so

all changes must be retested and re-evaluated by

appropriate users to ensure that changes are effective

and acceptable. Subsequent to user testing it is also

necessary to retest the web site for conformance to

the guidelines, as changes made during the user

testing updates may themselves be non-compliant.

This testing should also be done on normal site

updates before they are posted live. Finally, a

feedback form should be included with the web site

in the event that unforeseen problems arise for some

users. The feedback should be checked regularly and

any required changes made as soon as possible.

REFERENCES

Brewer, J., 2004 Web Accessibility Highlights and

Trends. Proceedings of W4A at WWW2004, May 18.

51-55. Retrieved December 13 2004 from

http://portal.acm.org

Disability Rights Commission, 2004. The Web: Access

and Inclusion for Disabled People, London. Retrieved

June 30, 2005 from http://www.drc-

gb.org/publicationsandreports/2.pdf

European Commission, 2001. eEurope 2002: Accessibility

of Public Web Sites and their Content. Retrieved June

28

2005 from http://europa.eu.int/eur-

lex/en/com/cnc/2001/com2001_0529en01.pdf

ICEIS 2008 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

110

European Commission & Council. 2000. An Information

Society For All: Action Plan. Retrieved June 28, 2005 from

http://europa.eu.int/information_society/eeurope/2002/

action_plan/pdf/actionplan_en.pdf

Gallaudet Research Institute, 2003. Literacy & Deaf

Students Retrieved April 20 2006 from

http://gri.gallaudet.edu/Literacy/#reading

Hackett, S., Parmanto, B. & Zeng, W., 2004. Accessibility

of Internet Websites through Time. Proceedings of

ASSEST’04, October 18-20. 32-39. Retrieved March 9

2005 from http://portal.acm.org

Irish Government, 1998. Employment Equality Act.

Retrieved March 30 2006 from

http://www.gov.ie/bills28/acts/1998/a2198.pdf

Irish Government, 2000. Equal Status Act. Retrieved 28

June 2005 from

http://www.oireachtas.ie/documents/bills28/acts/2000/

a800.pdf

Irish Government, 2005. Disability Act. Retrieved 30

March 2006 from

http://www.oireachtas.ie/documents/bills28/acts/2005/

a1405.pdf

Lazar. J., Beere, P., Greenidge, K. & Nagappa, Y., 2003. Web

Accessibility in the Mid-Atlantic United States: A Study of 50

Home Pages. Retrieved June 16 2005 from

http://triton.towson.edu/~jlazar/web_accessibility_in_us.pdf

Loiacono, E. & McCoy, S., 2004. Web site accessibility:

an online sector analysis. Information Technology &

People, 17(1), 87-101.Retrieved March 10 2005 from

http://www.emeraldinsight.com/0959-3845.htm

McMullin, B., 2002. WARP: Web Accessibility Reporting

Project Ireland 2002 Baseline Study. 1-82. Retrieved

March 15 2005 from http://eaccess.rince.ie/white-

papers/2002/warp-2002-00/warp-2002-00.pdf

Sullivan, T. & Matson R., 2000. Barriers to USE:

Usability and Content Accessibility on the Webs Most

Popular Sites. Proceedings of the Conference of

Universal Usability. Arlington VA: ACM, 139-144.

Retrieved December 13 2004 from

http://portal.acm.org

Takagi, H., Asakawa, C., Fukuda, K. & Maeda, J. (2004).

Accessibility Designer: Visualizing Usability for the

Blind. ACM SIGACCESS Accessibility and Computing

(77-78) 177-184. Retrieved March 9, 2005 from

http://portal.acm.org

Trulock, V., 2006. A Comparative Analysis of

Accessibility Levels of Irish Websites. MSc

Dissertation, Napier University.

W3C, 1999. Web Content Accessibility Guidelines.

Retrieved June 15 2005 from

http://www.w3.org/TR/WAI-WEBCONTENT

W3C, 2008. Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.0.

W3C Working Draft 11 December 2007. Retrieved

February 28 2008 from

http://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG20/

Williams, R. & Rattray, R., 2003. An assessment of web

accessibility of UK accountancy firms. Managerial

Auditing Journal, 9(18), 710-716. Retrieved March 10

2005 from http://www.emeraldinsight.com/0268-

6902.htm

ASSESSING THE PROGRESS OF IMPLEMENTING WEB ACCESSIBILITY - An Irish Case Study

111