DESIGNING BUSINESS PROCESS MODELS

FOR REQUIRED UNIFORMITY OF WORK

Kimmo Tarkkanen

Department of Information Technology, University of Turku, Joukahaisenkatu 3-5, Turku, Finland

Turku Centre for Computer Science TUCS, Joukahaisenkatu 3-5, Turku, Finland

Keywords: Business process modelling, modelling practice, work practice, uniformity.

Abstract: Business process and workflow models play important role in developing information system integration

and later training of its usage. New ways of working and information system usage practices are designed

with as-is and to-be process models, which are implemented into system characteristics. However, after the

IS implementation the work practices may become differentiated. Variety of work practices on same

business process can have unexpected and harmful social and economic consequences in IS-mediated work

environment. This paper employs grounded theory methodology and a case study to explore non-uniformity

of work in a Finnish retail business organization. By differentiating two types of non-uniform work tasks,

the paper shows how process models can be designed with less effort, yet maintaining the required amount

of uniformity by the organization and support for employees’ uniform actions. In addition to process model

designers, the findings help organizations struggling with IS use practices’ consistency to separate practices

that may emerge most harmful and practices that are not worth to alter.

1 INTRODUCTION

Common and ever-growing solutions of the last

decades have been ERP systems, which integrate

different business functions under shared application

and database. ERP systems embody expectations of

cost-effectiveness and improved cooperation

(Davenport, 1998), but invoke also hopes of

organizational integration and uniformity, as

systems are based on standardization and

centralization of both work processes and data.

Organizational formalisms, such as rules, guidelines,

and workflow models, are required for designing

these standardized business operations and

integrated information systems.

However, designs and descriptions of work

practices always tend to be more or less incomplete

(see eg. Suchman, 1987). Too vague model may not

act as a guide for a worker or give enough

operational support. On the other hand, very detailed

model may be too ruling for the worker in tasks that

do not need high conformance. Incompleteness of

process models may result also in computer

applications, which have functions and data fields

that are not needed or used in situated work.

Similarly, system functionality can be insufficient

and incomplete for work task accomplishment.

Either way, information system users are able to

work around with the system (Gasser, 1986) and

reconstruct the planned sequence of actions to match

their actual work process (Robinson, 1993). Without

these accommodating employees, computing and

work performance would degrade very rapidly at

significant organizational cost (Gasser, 1986). By

acting irrationally with computer, users actually

make systems more usable locally. Thus, deviations

from planned work actions are not always harmful,

but essential and inherent part of work activity.

Workarounds and unexpectedly acting workers

as well as those who act according to guidelines,

constitute together an occurrence of non-uniformity

- a group of people with minor or major differences

in their work practices. Such non-uniformity of

computer-mediated work practices has been found to

imply unexpected results (Koivisto, 2004, Mark and

Poltrock, 2003, Nurminen, Reijonen and

Vuorenheimo, 2003, Reijonen and Sjöros, 2001,

Prinz, Mark and Pankoke-Babatz, 1998). Significant

and harmful differences in information system use

emerged both between employees and between

communities (Koivisto, 2004). Non-uniformity

implied problems in individual work, in cooperation

21

Tarkkanen K. (2008).

DESIGNING BUSINESS PROCESS MODELS FOR REQUIRED UNIFORMITY OF WORK.

In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems - ISAS, pages 21-29

DOI: 10.5220/0001681500210029

Copyright

c

SciTePress

within work communities, in organizational

coordination activities and in evaluation of state of

affairs (Koivisto, Aaltonen, Nurminen and Reijonen,

2004). Productivity of work and usefulness of

system data can weak considerably because of non-

uniform system usage (Reijonen and Sjöros, 2001).

Disadvantages of non-uniformity show that system

use and system development need to be directed

toward the goal of supporting system usage by group

members so that their actions are congruent with

each other (Prinz, Mark and Pankoke-Babatz, 1998).

Related attempts have evolved continuously

throughout the years of computerization era. A need

of flexible and adaptive systems, system models and

business processes introduce one realisation. For

example, process modelling theory searches

adequate formality, granularity, precision,

prescriptiveness and fitness for the models (Curtis,

Kellner and Over, 1992) with different languages

and approaches. This becomes complicated, because

computer-mediated work is human work, which is

always shaped by freedom, opportunism and

recreation capabilities of rationality and norms

(Garfinkel, 1967, Giddens, 1984). Non-uniform acts

are more a rule than an exception in computer-

mediated cooperative organization environment.

As-is process models represent these non-uniform

acts when properly and truthfully built while to-be

models typically seek to determine organizationally

uniform best practices. Either type of model cannot

erase the occurrences of non-uniformity, but this

paper asks if the models and modelling practice can

be adjusted to consider the non-uniformity of work.

This paper focuses first on identifying different

non-uniform work practices and their causes and

consequences within a case organisation. Before

introducing the case in section 3, the next section

discusses a research methodology and data

collection and analysis methods. Section 4 describes

and models the non-uniform work practices of the

case organisation. Then, on section 5, the paper

answers the question of how process models

represented these non-uniform work practices and

furthermore draws conclusions for the modelling

practice to adapt to non-uniform work activity.

2 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

AND RESEARCH SITE

The research was conducted as cross-sectional,

although long-standing case study. A case study is a

part of qualitative research tradition, advantage of

which is that, it can increase the validity of the

research as the methodology allows comparisons of

data collected with different methods (Silverman,

1993). The case study was approached with the

grounded theory methodology, in order to reject a

priori theorizing and to use an iterative process of

constant comparison between data incidents,

emerging concepts and conceptual categories

(Glaser and Strauss, 1967).

The research site was chosen in respect to

grounded theory methodology. The research site is

one of the leading retail trade companies in Finland

and Baltic countries. This paper represents the

empirical findings of one sub-unit of the

organization: the unit of agricultural retail trade,

named here as AGRO. Two years ago, the

organization introduced a new organization-wide

information system. The new ERP system was to

cover all of the organization’s business areas and

units. The system was aimed at managing both

processes and data in daily basis. The system was in

go-live phase when the research started. This suited

well with the research setting as the concerns were

targeted on daily and routine work practices and

organizational impacts of non-uniformity. As the

AGRO unit is part of a larger organization, it was

positioned to follow the rules of organizational

standardization and change. With the chosen

methodology, this research aims to find and describe

non-uniform work practices within AGRO’s

information systems use.

2.1 Data Collection

This study views information system use as an

inseparable part of work activity (Nurminen and

Eriksson, 1999). The scope of the study is a work in

its richness and entirety, which may or may not

involve information systems use as a part of the

performance. The implication is that, in order to

relate the study with IS discipline the data collection

must be extended into such organizational

formalisms that determine information system usage

in business processes. It includes information

system’s user instructions, quality systems, business

process models and other guidelines for organizing

and managing work on the shop floor level.

In the first place, this collected material guides

the study to concentrate on work processes, which in

theory, should involve information systems use

actions regardless of the fact that computers may not

be used in situated work actions. Secondly, it gives

an understanding of the organizationally

documented and intended way to accomplish the

work processes and their expected results. Thirdly,

ICEIS 2008 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

22

the material plays a critical role in determining

which practices should be noted as uniform or non-

uniform from the organizational point of view.

Next, the data collection emerged through

observations, recorded interviews and informal

discussions. The total number of recorded interviews

was 26, from which a work of 18 different clerks

was observed. Interviews and observations took

place in 7 different grocery stores of AGRO around

Finland. Certain interview themes were repeated,

which included basic questions of job description,

work duties and responsibilities, as well as

communication patterns related to work processes.

The most important was to document the current

work practice. Employees were allowed and

encouraged to accomplish their routine work tasks

during the interviews. Due to this, interviews turned

to observing situations and contextual inquiry took

then place.

2.2 Data Analysis

Data collection and analysis occurred iteratively.

After an interview, the recorded data was

transcribed. Transcribed data provided insights into

employee’s situated work practices, faced problems,

and opinions about work. Based on the transcribed

data, workflow models of every work process and

process instances discussed in the interviews was

modelled. As regards the work practices, the purpose

of modelling was to reveal a) differences between

employees’ situated work practices and b)

differences between situated and organizationally

documented work practices. Firstly, data analysis

focused on comparing the modelled practices and

revealing non-uniformity in them. Constant

comparison of employees’ work practices directed

subsequent data collection. After identifying a

difference between practices, data collection and

analysis focused on the causes and consequences of

those practices. Evaluations of positive and negative

impacts of non-uniform practices were based on the

experiences of the clerks and other stakeholders of

doing the work. The evaluation proceeded from

individual to group, unit and organizational levels.

That kind of gradual evaluation offers a way for the

analysis of problems encountered in the use situation

of information technology (Kortteinen, Nurminen,

Reijonen and Torvinen, 1996).

As regards the process modelling itself, the focus

of the analysis is to find out how the observed non-

uniform activities emerge from the diagram and

method point of view. After identifying and

modelling non-uniform practices, the occurrences of

different practices were captured into one model.

Modelling technique was adapted from Sharp and

McDermott (2001), because it resembled the one

noted and applied by AGRO themselves during the

ERP implementation. However, the focus of the

paper is on modelling method and practice instead of

symbols and grammars used in specific modelling

languages.

The applied technique has a simple modelling

notation including three main components: roles

(actors), responsibilities (tasks) and routes (flow).

The models were built in three abstraction levels

with Microsoft Visio 2003. First level diagram

shows only hand-off situations, meaning that each

time an actor is involved in the process it is shown

with a single rectangle (Sharp and McDermott, 2001

p. 163). This level focuses on a workflow from one

actor to another. Second level diagrams show

significant milestones and decisions while actor has

the work, but not any details of how the actor should

do the tasks (Sharp and McDermott, 2001 p. 200). In

general, second level diagrams represent tasks that

cannot be excluded in order to achieve intended

result of the process. Third level adds more details

and logic on diagrams and contains individual steps

leading up to a certain milestone (Sharp and

McDermott, 2001 p. 163). A minor modification to

used notation was made: the tasks that were

accomplished with the information system were

drawn with database symbol instead of rectangle.

That was to help a reader to notify the use phases of

the ERP system.

3 MODELLING THE CASE

There were no pre-restrictions of which specific

work processes were to be under the study. Data

collection and analysis led to an identification of

seemingly typical and frequently executed work

processes throughout the AGRO organization. Work

processes related to clerks’ purchasing and selling

activities became central and got the focus of the

study. A business process called ‘direct delivery’

was one of these processes as it combines both

selling and purchasing transactions and it flows

through the different levels of AGRO. Direct

delivery is a special kind of sales process where

AGRO acts as an agency, a retail dealer, between

their end customers and product suppliers. In direct

delivery process, the company delivers the products

from a supplier to an end customer without any

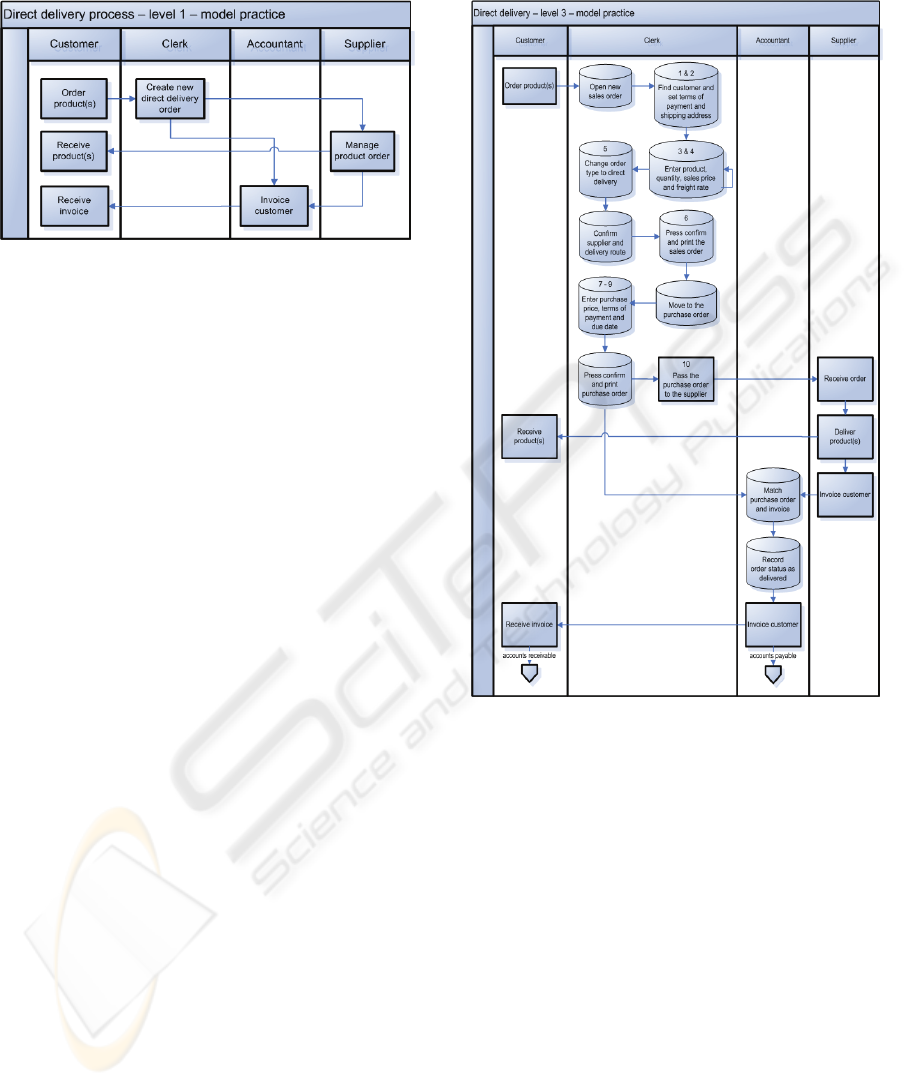

warehousing. Figure 1 represents organizationally

DESIGNING BUSINESS PROCESS MODELS FOR REQUIRED UNIFORMITY OF WORK

23

planned and accepted work practices of the direct

delivery process on level 1.

Figure 1: Hand-off diagram of the direct delivery process.

The clerks’ work consist of five milestones

during the process accomplishment: creating sales

order, converting the order type, recording sales

order, recording purchase order and sending order to

the supplier.

The direct delivery process begins when an end

customer expresses a need for a not-at-the-stock

product of the AGRO company. First, a clerk at the

company fills a new sales order in the IS with the

specific product information (i.e. quantity, price etc.)

and the end customer information (i.e. name,

delivery address, terms of payment etc.). After

filling the sales order, the clerk converts it to a direct

delivery type of order by selecting a corresponding

system function. In practice, the conversion itself is

an automatic creation of a new purchase order based

on the information entered on the sales order. The

clerk records the sales order and prints it for a

backup copy of the customer transaction.

The clerk moves to created purchase order and

reviews the purchase information, like purchase

prices and special terms for payment. Usually the

purchase prices are available on an updated price list

of the supplier. The clerk may also agree special

purchase prices with the supplier. Reviewing is

finished when the purchase order is recorded and

printed. The actual purchase transaction to the

supplier takes place through a telephone call, fax, or

filling a form on supplier’s website.

Product transportation is managed either by the

supplier, by external transportation provider or by

the company’s own transportation resources. The

supplier supplies the products to the end customer

and sends the invoice to the company accountant.

The accountant matches the arrived invoice and the

purchase order on the IS using the reference note on

the invoice. Lastly, the accountant sends the sales

invoice to the customer. Figure 2 represents the

workflow of the direct delivery on more detailed

level.

Figure 2: Detailed model of the direct delivery process

(level 3 diagram).

4 NON-UNIFORMITY OF WORK

After data analysis had begun, it became apparent

that direct delivery process embedded also variety of

different work practices during the process

accomplishment. Ten non-uniform work practices in

this workflow were found among the clerks

interviewed (table 1).

ICEIS 2008 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

24

Table 1: Causes and consequences of non-uniform work practices.

Non-uniform work practice Causes Consequences

(1) The clerks do not charge for

billing.

The customers are not willing to

pay the billing charges.

Increased customer satisfaction (+). Billing

charges are lost (-).

(2) Customer-specific special terms

are kept on the paper notes.

Customer-specific discount

percents in the IS are followed

with every product transaction for

this customer.

Given discounts are considered more

carefully based on product type (+). Other

clerks cannot be aware of customer-specific

special terms (-).

(3) Freight rates of the sales orders

are entered separately for different

products.

Need for improved service and

avoidance of misunderstandings

by improved documenting.

Increased customer satisfaction. (+).

(4) Product discounts are subtracted

from the total costs and discount

field is set to zero.

Lack of skills in using discount

field.

Quicken work (+).

(5) Direct delivery type of sales

transaction is performed using the

separate purchasing and selling IS

functions successively.

A common way to perform the

task in the old system.

When using separate functions, the clerks

are more aware and can control more the

movements of the products from one place

to another (+). The clerk must perform

extra work tasks (-).

(6) Confirmations of the sales

orders are not printed.

Printed sales orders are not

needed by the clerks.

Economizing paper costs and minimizing

space requirement (+). Backup of the sales

transaction is not present when needed (-).

(7) Freight rates are entered on the

purchase orders.

Lack of use skills. Freight rate may be invoiced twice.

Additional financial expenses (-).

Decreased supplier satisfaction (-).

(8) Purchase prices are not revised

when fulfilling the purchase order.

The clerk wants to ease his job

and follow the prices of the

invoice.

The clerk does not know the

correct purchase price.

Work process is extended and delayed

(accountant sends the invoice to the clerk,

who enters the order into IS and returns the

number of the order to accountant) (-).

(9) Purchase price is set

unreasonable high.

The clerk wants to be contacted

by the accountant and have extra

information concerning the

purchase transaction.

Erroneous data in the purchase price field

can result financial expenses, if transferred

into real payment transactions (-).

The clerk can produce improved results of

the purchasing process with the extra

information (+).

(10) Purchase orders are entered

into the IS after making the order

by telephone, or after the product is

delivered, or after the purchasing

invoice has arrived.

Employee is busy with other work

and there is a hurry to place the

order to the supplier.

It is easier to fill the purchase

order after the purchase invoice

has arrived, because the clerk can

follow the information on the

invoice (e.g. can set the purchase

prices correctly).

Accountant cannot find the purchase order

from the IS and cannot match the order and

the arrived invoice (-).

Work process is extended and delayed

(accountant sends the invoice to the clerk,

who enters the order into IS and returns the

number of the order to the accountant) (-).

DESIGNING BUSINESS PROCESS MODELS FOR REQUIRED UNIFORMITY OF WORK

25

Creating a new sales order embedded four non-

uniform work practices. Since the task is an

interactive situation with customer, the clerk needs

to listen customer demands and follow their

preferences. For example, some of the regular

customers with a long time business relationship

were not delighted if they had to pay billing charges

when ordering products. Hence, sometimes,

depending on customer, the clerk did not enter the

billing charges on the sales order to maintain a good

customer relationship (practice 1). In many cases a

customer makes a short telephone call to order

products. During the call, the clerk must make a

reminder note of the order details on paper book.

The clerks’ make order notes on book also when

they are busy with other work, are not present at the

work place or faced to a computer. Eventually a case

was that the new sales orders were entered

periodically into ERP. Some of the clerks kept also

the customer-specific special terms on the paper

notes instead of the ERP database, even if system

fields were available (practice 2). After specifying a

customer, the clerks continued entering products,

freight rates and price discounts with varied

practices. For example, some of the clerks entered

the freight rates separately for every product instead

of using summarized freight rate (practice 3), which

was intended action. Very alike, but converse action

occurred with product discounts. Instead of using the

discount field of every product, some calculated

total discount and subtracted it from the total costs

and left discount fields empty (practice 4).

It was also possible to perform direct delivery

type of process without using the corresponding

function of IS at all (practice 5). Practically the clerk

used two separate selling and purchasing functions

instead of automated conversion to direct delivery.

Another exclusion of work task happened with sales

order printing task. Some clerks regarded printing

the sales order as useless, more of waste of paper,

than an important backup copy of the transaction

(practice 6). After recording the sales order,

purchase order fulfilling and sending took place with

three more non-uniform practices. First, freight rates

were entered on the purchase order, even if the

system generated the rates automatically from the

filled sales order (practice 7). Another non-uniform

practice was related to price verification when

fulfilling the purchase order. Occasionally the clerks

did not check if the system recommended price was

correct (practice 8). Thus, if the price was not same

on the supplier’s invoice and the purchase order, the

accountant had to contact the clerk for

troubleshooting. Interestingly, some clerks wanted to

be contacted by the accountant and on purpose set

the price incorrectly (practice 9). The most common

and frequently emerging non-uniform practice was

to place the purchase order before filling the sales

order (practice 10). That turned the workflow upside

down and affected also on other later practices of

clerks and accountants.

5 MODELLING FOR REQUIRED

UNIFORMITY OF WORK

The findings of the previous section show that the

models of direct delivery process could not describe

the non-uniform work practices in an appropriate

level of detail. Even if the model of the figure 2 is

detail and operational, it has only slight

correspondence with the situated actions. At best,

the model captures one non-uniform work practice

into one modelled task. However, this modelled task

embeds other work practices as well and therefore is

not at the level of detail of non-uniformity. The

AGRO case findings support the notion by Ellis

(1999) that “[e]xperience has shown that within a

single process, there is a need to model different

parts in different amount of detail, and different

levels of operationality.”

According to Model Domain Space (Nutt, 1996)

and CDO-model (Ellis, 1999), the necessary level of

detail of the model is dependent on the amount of

conformance and operational support required by the

organization. The course of relation between these

dimensions are not totally orthogonal, but rather

vague (Ellis, 1999). For example, more details in a

workflow model do not necessarily provide more

operational support for the worker, nor guarantee

any conformance of the situated work actions. The

AGRO models show that fixing the levels of detail

of the models before determining the needed

conformance and nature of operational support does

not support uniformity of work or designing for it.

Furthermore, the level of detail is, first of all,

defined by the model designer and the modelling

technique. Thus, level of detail is somewhat

artificially created variable for the model, where as

the level of conformance is based on the actual

requirements of a work process and is set by the

work organization.

For the organization, determining the necessary

level of conformance for the work process can have

a basis on the evaluation of the effects of non-

uniformity. In other words, there is no need for high

conformance on a task if less conformity does not

ICEIS 2008 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

26

mean harmful consequences for the business and

parties involved in the process. Using this evaluation

criterion to the AGRO case results, we can

determine the necessary level of conformance for the

direct delivery process. Non-uniform practices that

have only positive effects, like practices 3 and 4 (see

table 1), indicate that there is no need for more

uniformity on these tasks. As opposite, the practices

that have only negative impacts (7, 8 and 10) imply

a greater need for conformance. However, the other

practices introduce both positive (+) and negative (-)

effects and more holistic evaluation of consequences

is needed. Reviewing the intents of the actors and

the criticality of possible effects on different

organizational levels, we find that practices 7-10

introduce more harmful effects than practices 1-6.

For example, not charging the customer for billing

(practice 1), was well-intentioned and had positive

influence for customer loyalty where as the lost of

incomes of this practice can be regarded as

insignificant consequence on the large scale. The

practices 1-6 and 7-10 have also another

classification; the latter practices are hand-off

situations whereas first six practices are not. Sharp

and McDermott (2001) define hand-off tasks as

those passing the control of work to another actor

(outgoing flow). Opposite to hand-off tasks, on first

six non-uniform practices, the actors have the work

item and operate it themselves through these phases.

Thus, the AGRO case findings suggest that other

than hand-off tasks introduce variance that is

positive for current process instance whereas hand-

off tasks introduce variance that effects negatively

for the same process instance.

Organizations implementing a new or analysing

current information system face a great need to

minimize the work effort of modelling. The

modelling technique used in the AGRO case has a

simple notation, which makes it rather attractive

option for time-, cost- and resource-limited IS

customer organizations. According to Mackulak,

Lawrence and Colvin (1998), the cost of modelling

is minimized when only necessary amount of details

are embedded into models. The AGRO case findings

suggest that it would be applicable to avoid details

with the tasks that are not hand-off tasks. In other

words, three level abstractions are not used with

tasks that introduced positive variance. The benefit

is that instead of focusing on every step on the

process, the focus is targeted only to minor parts of

the whole process. Aggregated modelling of these

“on-hand” tasks will sustain an adequate level of

conformity, because those do not introduce negative

variance. From the modelling point of view, what

we can do with greater conformance need of

practices 7-10, is try to add more details and

operational nature to the model and hope that it is

also realized in actual work practice. More accurate

model is created either by adding more details on

naming (see Ellis, 1999) or by continuing the

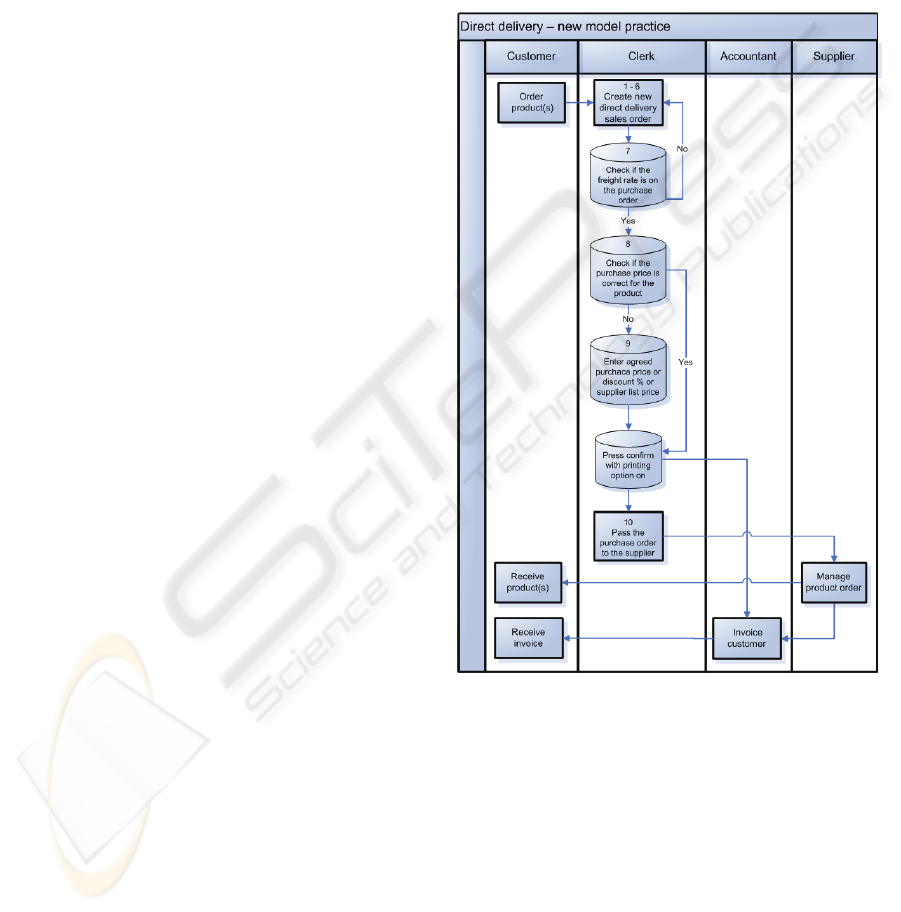

focusing on smaller subtasks. In figure 3, the direct

delivery process of AGRO is re-modelled more

effectively concerning the required amount of

uniformity.

Figure 3: Direct delivery process with necessary level of

details for uniformity in situated work.

As the figure 3 shows, the model mixes different

abstraction levels (between practices 1-6 and others).

In practice, adding details (i.e. abstraction levels)

only to hand-off tasks can be tricky. The focusing

typically entails that not all steps are hand-off steps

anymore. In the AGRO case, after building the

hand-off diagram and identifying two hand-off tasks

record the purchase order and pass the purchase

order to the supplier, the former enlarges on level 3

diagram into three different steps (figure 2) where

only two steps introduce hand-off. One must then

define what steps of this hand-off task to model with

DESIGNING BUSINESS PROCESS MODELS FOR REQUIRED UNIFORMITY OF WORK

27

more details, if not all. Without any exact rules and

limitations the focusing may become endless and

certainly not a cost-effective option. In the AGRO

case, the focusing was easy as the non-uniform

practices were identified beforehand. The modelling

procedure applied in re-modelling the direct delivery

process of AGRO is represented on table 2. This

procedure led to a cost-effective process modelling

for required amount and support of uniform work

actions.

Table 2: Process modelling procedure for required

uniformity of work.

Process Modelling Procedure

for Required Uniformity

PHASE 1: Model the hand-off diagram

PHASE 2: Identify the work tasks that lead

into new hand-off situation

PHASE 3: Identify individual steps of every

hand-off task

PHASE 4: Model step(s) found in phase 3 with

more details into the hand-off

diagram

The modelling effort begins with the most

abstract level, in this case, with modelling the hand-

off diagram. At second phase, the work tasks that

lead to a hand-off are identified. Third phase is to

identify individual steps within the hand-off task and

expand the created first level model with these

individual steps. The new AGRO model, created

with this procedure, remains understandable in the

context it is used; the modelled steps are comparable

to units in reality and it is still a representation of a

real world.

6 FUTURE RESEARCH

Non-uniformity of work practices touches

information systems research fields from systems

design to CSCW issues. It is especially interesting

research area in the field of organizational

implementation and process modelling, which affect

later information system use and work practices

turning non-uniform or not. Non-uniformity of work

can have either serious or almost innovative impact

on different levels of organization. Different

business units may also vary in their processes and

data after the enterprise systems-enabled integration

(Volkoff, Strong and Elmes, 2005). The case of

AGRO gave an opportunity to analyse this variation

from process models point of view in one

organizational unit and draw conclusions for

modelling method improvements. First, the findings

are useful for the AGRO in their future modelling

and work standardizing practices within and

between the units. How this developed procedure

would be applicable for harmful non-uniformities in

another organizations’ processes calls for further

research.

Raising questions are also those that investigate

the realisation of benefits of using the procedure in

terms of time and work effort needed. By gathering

data from many organizations and business

processes, it would be possible to define further

these gaps between process models and process

instances and develop efficient methods to

determine necessary level of details and

conformance for the process models while the

organisation is reaching for more standardized

practices. This would require systematic evaluation

of impacts of non-uniform IS practices based on for

example practical business process evaluation

methods. A recently introduced ProM framework

provides a promising technically-oriented and real-

time approach to identify and measure impact of

non-uniform acts based on information system event

logs (Rozinat and van der Aalst 2005, Verbeek, van

Dongen, Mendling and van der Aalst, 2006).

However, in order to reveal tacit and intangible

causes and consequences of non-uniformity we may

still need to exploit methods of qualitative field

research. Business process models and modelling

itself, as highly subjective and designer-dependent

matters, set a challenge for research validity.

Therefore, also validation of findings with different

modelling techniques and by different process

modellers would be needed in the future.

REFERENCES

Curtis, B., Kellner, M. I., Over, J., 1992. Process

Modelling. Communications of the ACM, 35, 75-90.

Davenport, T. H., 1998. Putting enterprise into enterprise-

system. Harvard Business Rev iew, 3, 121-131.

Ellis, C. A., 1999. Workflow Technology. In Computer

Supported Cooperative Work (pp. 29-54), John Wiley.

Garfinkel, H., 1967. Common sense knowledge of social

structures: the documentary method of interpretation

in lay and professional fact finding. Studies in

Ethnomethodology (pp. 76-103). Prentice-Hall, New

Jersey.

ICEIS 2008 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

28

Gasser, L., 1986. The integration of computing and routine

work. ACM Transactions on Office Information

Systems 3, 205-225.

Giddens, A., 1984. The Constitution of Society. Outline of

the Theory of Structuration. Cambridge.

Glaser, B. G., Strauss, A., 1967. The Discovery of

Grounded Theory: Strategies For Qualitative

Research. Aldine, New York.

Koivisto, J., 2004. Drifting work practices after EPR

implementation: The case of a home health care

organization. 4S/EASST, Public proofs - science,

technology and democracy. 25-28.8.2004, Ecole des

Mines de Paris, France.

Koivisto, J., Aaltonen, S., Nurminen, M. I., Reijonen, P.,

2004. Työkäytäntöjen yhtenäisyys tietojärjestelmän

käyttöönoton jälkeen – tapaustutkimus Turun

terveystoimen kotisairaanhoidosta. (Uniformity of

work practices after IS implementation – a case study

in home care.) The Finnish Work Environment Fund –

project 990327. Turku Municipal Health Department

Series A, 1/2004.

Kortteinen, B., Nurminen, M. I., Reijonen, P., Torvinen,

V., 1996. Improving IS deployment through

evaluation: Application of the ONION model. In A.

Brown & D. Remenyi (eds.) The Proceedings of Third

European Conference on the Evaluation of

Information Technology, 29 November 1996, Bath,

UK. pp. 175 - 181.

Mackulak, G. T., Lawrence, F. P., Colvin, T., 1998.

Effective Simulation Model Reuse: a case study for

amhs modelling. Proceedings of the 1998 Winter

Simulation Conference, pp. 979-984.

Mark, G., Poltrock, S., 2003. Shaping Technology Across

Social Worlds: groupware adoption in a distributed

organization. In K. Schmidt, M. Pendergast, M.

Tremaine & C. Simone (eds.) Proceedings of the

International ACM SIGGROUP Conference on

Supporting Group Work, GROUP’03, November 9–

12, 2003, Sanibel Island, Florida, USA, pp. 284-293.

Nurminen, M. I., Eriksson, I., 1999. Research notes

Information systems research: the ’infurgic’

perspective. International Journal of Information

Management, 19, 87-94.

Nurminen, M., I., Reijonen, P., Vuorenheimo, J., 2002.

Tietojärjestelmän organisatorinen käyttöönotto:

kokemuksia ja suuntaviivoja. (Organizational

implementation of IS: experiences and guidelines).

Turku Municipal Health Department Series A, 1/2002.

Nutt, G. J., 1996. The Evolution Towards Flexible

Workflow Systems. Distributed Systems Engineering,

3, 276-294.

Prinz, W., Mark, G., Pankoke-Babatz, U., 1998. Designing

groupware for congruency in use. Proceedings of the

1998 ACM conference on Computer supported

cooperative work, pp. 373 – 382.

Reijonen, P., Sjöros, A., 2001. Toimintatapojen

vakiintuminen tietojärjestelmän käyttöönoton jälkeen.

(Stabilization of the work practices after IS

implementation). SoTeTiTe 2001 Conference, Kajaani,

Finland 3-5.6.2001.

Robinson, M., 1993. Design for unanticipated use.

Proceedings of the third conference on European

Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative

Work, pp. 187 – 202.

Rozinat, A., van der Aalst, W. M. P., 2005. Conformance

testing: Measuring the fit and appropriateness of event

logs and process models. Business Process Modelling

BPM 2005 Workshops, LNCS 3812, Springer-Verlag

Berlin Heidelberg 2006, pp. 163-176.

Sharp, A., McDermott, P., 2001. Workflow Modelling:

tools for process improvement and applications

development. Artech House, London.

Silverman, D., 1993. Interpreting qualitative data. Sage,

London.

Suchman, L., 1987. Plans and Situated Actions: The

Problem of Human-Machine Interaction. Cambridge

University Press.

Verbeek, H. M. W., van Dongen, B. F., Mendling, J., van

der Aalst, W. M. P., 2006. Interoperability in the ProM

framework. In T. Latour and M. Petit (eds.):

Proceedings of the CAiSE’06 Workshops and

Doctoral Consortium, Luxenbourg. Presses

Universitaries de Namur, pp. 619-630.

Volkoff, O., Strong, D. M., Elmes, M. B., 2005.

Understanding enterprise systems-enabled integration.

European journal of Information Systems, 14, 110-

120.

DESIGNING BUSINESS PROCESS MODELS FOR REQUIRED UNIFORMITY OF WORK

29