DO

SME NEED ONTOLOGIES?

Results from a Survey among Small and Medium-sized Enterprises

Annika

¨

Ohgren and Kurt Sandkuhl

School of Engineering at J

¨

onk

¨

oping University, P.O. Box 1026, 55111 J

¨

onk

¨

oping, Sweden

Keywords:

SME, Ontology Construction, Ontology Engineering, Survey, Product Complexity, Project Complexity.

Abstract:

During the last years, an increasing number of successful cases of using ontologies in industrial application

scenarios have been reported, the majority of these cases stem from large enterprises. The intention of this

paper is to contribute to an understanding of potentials and limits of ontology-based solutions in small and

medium-sized enterprises (SME). The focus is on identifying application areas for ontologies, which motivate

the development of specialised ontology construction methods. The paper is based on results from a survey

performed among 113 SME in Sweden, most of them from manufacturing industries. The results of the survey

indicate a need from SME in three application areas: (1) management of product configuration and variability,

(2) information search and retrieval, and (3) management of project documents.

1 INTRODUCTION

During the last years, an increasing number of suc-

cessful cases of using ontologies in industrial appli-

cation scenarios have been reported, see for exam-

ple (Lau and Sure, 2002) and (Sandkuhl and Billig,

2007). However, the majority of these cases stem

from large enterprises, or IT-intensive middle-sized or

small enterprises (SME). Most SME outside the IT-

sector probably never have heard about ontologies.

Do these SME really need ontologies? Are there

shortcomings and a need for improvement in appli-

cation areas where the use of ontologies can create

substantial benefits? Existing studies about IT use in

SME, like (Lybaert, 1998), do not cover ontologies

or knowledge representation techniques sufficiently.

Studies focusing on usage of innovative ICT technol-

ogy, like (Koellinger, 2006), target a wider audience

than SME.

Considering the characteristics of successful cases

in larger enterprises, similar cases should also exist

in SME, but drawing conclusions from experiences

of larger enterprises with regards to SME is not rec-

ommendable, as SME have their own characteristics

(Levy et al., 2002): SME often belong to the group of

”late adopters” of new technology, i.e. they prefer ma-

ture technologies, which are easy to deploy, use and

maintain. SME show a clear preference for to a large

extent standardised solutions. Innovation projects in

SME typically have to create business value within a

short time frame.

The intention of this paper is to contribute to an

understanding of potentials and limits of ontology-

based solutions in SME with a focus on ontology ap-

plication areas. The paper is based on results from

a survey performed among SME in Sweden. The re-

mainder of the paper is structured as follows: in sec-

tion 2 we discuss background work together with the

aim of the conducted survey. The survey setup is de-

scribed in section 3. In section 4 the results of the

survey are described. A discussion of the survey re-

sults regarding aim etc. is found in section 5. Finally,

in section 6 conclusions are drawn.

2 BACKGROUND

This chapter briefly illuminates three aspects, which

form an important background for the remaining part

of the paper.

• In section 2.1: For what purpose and in what areas

could SME possibly use ontologies?

• In section 2.2: How to judge whether there is an

application potential in the identified areas?

• In section 2.3: To which research activities in on-

tology engineering is the survey supposed to con-

tribute?

104

Öhgren A. and Sandkuhl K. (2008).

DO SME NEED ONTOLOGIES? - Results from a Survey among Small and Medium-sized Enterprises.

In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems - ISAS, pages 104-111

DOI: 10.5220/0001704201040111

Copyright

c

SciTePress

2.1 Application Areas for Ontologies

The literature in the area of ontology engineering

identifies a variety of different applications in many

different areas. In (Obitko, 2001) the authors describe

some: ontologies can be used for expressing domain-

general terms in a top-level ontology, for knowledge

sharing and reuse, for communication in multi-agent

systems, natural language understanding, and to ease

document search to mention some of them.

Uschold and Gr

¨

uninger specify three different cat-

egories where ontologies can be used, see (Uschold

and Gruninger, 1996). The first is communication:

ontologies can be used to increase and facilitate com-

munication among people. The second usage area de-

fined is inter-operability. Ontologies can serve as an

integrating environment for different software tools.

The third usage area is systems engineering, in which

ontologies can play an important part in the design

and development of software systems. They can help

to identify requirements of a system and to explicitly

define relationships among components of a system.

They can also be used to support reuse of modules

among different software systems.

In (McGuinness, 2002) several application areas

for ontologies are mentioned. Ontologies can be used

for navigation, browsing, and search support. Consis-

tency checking can also be handled with ontologies

to some extent. Ontologies can provide configuration

support and support validation and verification testing

of data.

Within OntoWeb four different usage areas for

ontologies are defined, as seen in (Ontoweb, 2004):

enterprise portals and knowledge management, e-

commerce, information retrieval, and portals and web

communities. In this context, information retrieval

means to use ontologies for understanding the con-

cepts being searched and avoid the mistake of missed

positives (failure to retrieve relevant answers) and

false positives (retrieval of irrelevant answers).

When analysing the above sources, four applica-

tion areas of ontologies in enterprises are named sev-

eral times. These four application areas will be used

as starting points for identifying ontology application

fields of relevance for SME:

• navigation, browse, and search support for infor-

mation retrieval in enterprises or for managing

documents,

• capturing and representing knowledge for the pur-

pose of knowledge sharing,

• configuration and validation support of products

like software systems,

• supporting inter-operability between different IT-

systems, e.g. in a collaboration between customer

and supplier.

2.2 How to Judge Ontology Application

Potential?

The previous section identified application areas for

ontologies, which potentially are of interest for SME.

One task of the planned survey will be to confirm

that these fields really can be found in the SME sam-

ple under consideration, i.e. that a sufficient part

of the SME have product configuration challenges,

need support in document or information retrieval, or

work in collaboration projects with suppliers requir-

ing inter-operability.

The mere existence of an application field alone,

however, does not indicate that the use of ontologies

is appropriate in this field. Small projects or sim-

ple product configurations, to just take two examples,

might well be manageable in an efficient way without

any IT support at all. How to judge when it makes

sense to consider the use of ontologies? In this pa-

per we will follow the opinion of various scholars in

the field that the complexity of an application case is

an essential parameter to take into account when de-

ciding about the use of ontologies. The more com-

plex the application scenario, the more likely the use-

fulness of ontologies. In the context of this paper,

project complexity and product complexity are of par-

ticular interest. Approaches for determining or even

measuring project complexity and product complex-

ity could directly contribute to identifying the share of

SME with either complex project situations or com-

plex products.

A review regarding the concept of project com-

plexity performed by Baccarini (see (Baccarini,

1996)) proposes to define complexity as ”consisting

of many varied interrelated parts”, to distinguish be-

tween organisational and technological complexity,

and to operationalise this in terms of ”differentiation

and interdependence”. Differentiation refers to the

number of varied elements, e.g. tasks or components;

interdependence characterises the interrelatedness be-

tween these elements. Regarding organisational com-

plexity, Baccarini identified among other indicators

the number of organisational units involved and the

division of labour. For technological complexity, the

diversity of inputs and output and the number of spe-

cialities (e.g. subcontractors) are considered.

In the area of product complexity, work of Hob-

day, see (Hobday, 1998), regarding distinctive fea-

tures of complex products and systems identifies di-

mensions defining the nature of a product and its com-

DO SME NEED ONTOLOGIES? - Results from a Survey among Small and Medium-sized Enterprises

105

plexity. The not exhaustive list of 15 critical prod-

uct dimensions provided by Hobday includes quantity

of sub-systems and components, degree of customisa-

tion of products and intensity of supplier involvement.

These dimensions will be used in combination with

Baccarini’s project complexity indicators when eval-

uating the survey results in section 5.

2.3 Previous Work on Ontology

Construction Methods

The work presented in this paper is part of a research

program focusing on industrial applications of enter-

prise ontologies, with particular focus on SME. The

overall intention is to lower the threshold for adap-

tation of ontology-based applications in industry by

reducing time and costs for ontology development.

Previous work focused on analysing existing ontology

development methods with respect to their suitability

for SME, see (

¨

Ohgren and Sandkuhl, 2005), and on

proposing and applying a newly developed method in

this context, see (Blomqvist et al., 2006). Although

the initial experiences with the new method were pos-

itive, the conclusion was that a further specialisation

would be recommendable.

In order to prepare this specialisation, the de-

mands of SME and the relevance of ontologies for

different application fields had to be investigated. The

survey presented in this paper was performed in or-

der to contribute to this objective. Thus, the sur-

vey focused on the applications, requirements and

shortcomings perceived by the users in the enterprises

rather than on the IT-solution aspects, i.e. details of

IT-infrastructure or IT in use.

3 SURVEY SETUP

Based on the background work described in 2.1, the

following five conjectures were defined regarding the

application areas for ontologies in SME.

1. There is a need for supporting information search-

ing and thus reducing the time needed to find the

right information.

2. There is a need for supporting management of

configurations or variations of products. This

could be differences and similarities, dependen-

cies between variants of a product, or dependen-

cies between products, which could be used for

example to improve reuse of parts of products

and/or reuse of design processes.

3. There is a need for structuring documents and

supporting document management, for example

in order to support project work.

4. There exists a need for supporting collaboration

and inter-operability in networks of companies,

and/or supply chains.

5. There is a need for capturing enterprise knowl-

edge, like development rules, process knowledge,

or design principles in order to avoid dependen-

cies from certain individuals.

3.1 Interviews

Prior to the survey interviews were held in order to

investigate how to proceed within the previously dis-

cussed application areas. In total eleven people from

seven companies were interviewed to see their view

on potential problems and ideas regarding the conjec-

tures and to identify suitable fields and questions for

a questionnaire survey. The companies’ sizes ranged

from three employees up to 2300. The companies also

differed in type and industrial sectors.

The interviews resulted in the decision to go on

with a questionnaire to further investigate the first

three conjectures listed above, namely information

searching, configurations/variants of products and

document management.

According to the interviewees most information

within the field of supply chain or networks of en-

terprises is based on personal experience, which was

deemed very hard or even not possible to document.

The conclusion here was not to continue with the two

last conjectures, i.e. with both supply-chains and net-

work of enterprises, and documenting expert knowl-

edge.

3.2 Survey Layout

The questionnaire finally consisted of 35 questions

on six pages. The questionnaire was divided into

six parts in varying size, where the first four ques-

tions concerned the company: number of employees,

yearly turnover, industrial sector, and the respondent’s

role within the company.

The next part was related to conjecture 1, included

ten questions, and dealt with document and informa-

tion management. This part included questions about

how much time the respondent used daily to find and

save information connected to his or her work, where

to find this information, etc.

The third part, which was connected to conjec-

ture 3, concerned only companies working in projects

and included six questions about the number of em-

ployees in each project, how long time the projects

ran, and some information about the documents in the

projects.

ICEIS 2008 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

106

The following eleven questions were related to

conjecture 2 and targeted only producing companies.

These questions addressed how many products the

company had, how many components each product

consists of, how many suppliers that contribute to

each product, and in how many variants each product

is made.

Finally there were questions regarding non-

documented personal knowledge and regarding tax-

onomies and nomenclatures. The answers to these

questions will not be discussed in section 5 as they

are not related to the conjectures.

3.3 Sample

In order to reach out to an appropriate number of

companies, the schools host company database was

used. These companies already have a connection to

the school and were therefore deemed more interested

in responding to such a questionnaire than companies

without an established connection to the education

and research performed at the school. The database

also includes contact persons at each company, to

whom the questionnaire was directly addressed to.

The questionnaire was sent to 436 companies in

the end of 2005. 24 of the sent questionnaires came

back unopened due to wrong addresses or unknown

addresses, which means that the number of possible

respondents was reduced to 412. 164 answers were

received, all of them were considered useful and were

used in the analysis, giving a response rate of 39,8%

(164/412), which is considered to be quite high.

Among the 164 returned questionnaires, 51 were

returned by large companies, i.e. companies with

more than 250 employees or more than 400 Mio SEK

yearly turnover (approx. 43 Mio EUR). The size of

the sample taken into account for this paper is 113

small and medium-sized enterprises with approx. half

of them with less than 50 employees.

4 SURVEY RESULTS

This section presents the results of the survey. The

section is structured into three parts, which corre-

spond to the conjectures introduced in section 3:

retrieving information and documents (4.1), prod-

uct complexity (4.2) and document management in

projects (4.3).

4.1 Retrieving Information and

Documents

In the survey, a clear majority of the sample perceive

that they receive ”far too much” (41%) or ”too much

information (28%). 27% think the amount of infor-

mation is adequate, only 4% think they do not receive

enough information.

Regarding the time needed daily to find the right

information for the work at hand, the distribution is

as shown in figure 1. Even though half of the sam-

ple needs less than half an hour daily to find the right

information, it can be noted that a substantial part of

the working hours is consumed by searching for in-

formation. 33% of the sample consume up to an hour

daily, 11% need more than one hour, 5% even more

than two hours.

> 12060-12030-6010-30< 10

40

30

20

10

0

Percent

Figure 1: Time needed daily to find the right information

for the work at hand (in minutes).

The participants were also asked how difficult it

is to find the information needed for the work task at

hand. Within the sample, nobody answered that it is

”very difficult” to find the required information. ”Rel-

atively easy” and ”medium difficult” both received

approx. 40%; ”very easy” and ”difficult” both ap-

prox. 9%. Not surprisingly, the respondents with a

higher daily time effort for finding information also

had a tendency to perceive it as more difficult to find

the right information.

Concerning the sources for finding required infor-

mation, joint file servers in the companies and the In-

ternet are the most often used sources, followed by the

own PC: 70% answered that the file server is ”often”

or ”very often” the source for information, 64% the

Internet and 49% the own PC. Intranet and document

management systems (DMS) are less frequently used

(36% and 26%, respectively), which to some extent

will be based on the fact that 29% of the sample do

not have an Intranet and 31% do not have a DMS.

The established DMS and Intranet solutions in en-

terprises are used quite intensively: 40% of all re-

spondents use these systems several times a day, 29%

nearly every day. 17% use these IT-systems a few

times during the week and 14% use them only a few

DO SME NEED ONTOLOGIES? - Results from a Survey among Small and Medium-sized Enterprises

107

times in a month or even more seldom.

Regarding the question how to find the requested

information in the above mentioned sources, most re-

spondents rely on their memory from earlier cases

(67%), use keyword search (60%) or the existing di-

rectory structure (59%). Furthermore, a substantial

part of the respondents ask their colleagues for the

needed information (29%).

Considering the potential for improving informa-

tion management in SME, not only the introduction

of Intranet or DMS in companies without those sys-

tem types is a possibility, but also the improvement of

these systems as such. Among the respondents who

have an Intranet or DMS 50% of the respondents note

that it is not possible to subscribe new or changed

information, 17% stated that they got too many hits

when searching for information, 19% claimed they

got irrelevant hits, and others wish for an improved

structure of the information, either with relation to the

work process (19%), or with regards to the product

structure used in the company (33%).

4.2 Product Complexity

Another part of the survey was addressing the issue

of product complexity. In industry domains devel-

oping or manufacturing physical products, the num-

ber of components in the product, potential versions

and variants of the product and number of suppliers

contribute to product complexity. The product related

part was answered by 61 of 113 SME. The following

part of the results is based on these 61 responses.

The number of products found in the sample was

quite high: 62% of all respondents stated that they

have more than 50 products. 5% and 13% have be-

tween 11 and 25 or between 26 and 50 products, re-

spectively. 15% of all respondents have between 4

and 10 products, 5% even less than 4 products.

Most of the products have a small number of vari-

ants. 47% of the respondents answered that there are

on average less than 6 variants, 23% between 6 and

12. 4% stated that there are between 13 and 25 vari-

ants, 9% between 26 and 50, and 17% more than 50

variants.

The average number of components in these prod-

ucts is either quite high or quite low. 35% of the re-

spondents state that a product on average has more

than 50 components. 42% have less than 10 compo-

nents per product (23% less than 4 components; 19%

between 4 and 10). 21% state the average number is

between 11 and 25. At 2% of the respondents it is

between 26 and 50.

In the large majority of the enterprises, a descrip-

tion is available which components are parts of what

product: 88% answered that some kind of product

structure exists, 8% answered there is no such struc-

ture, the remaining did not know. The existence of

such a description or product structure would ease the

development of an ontology in the field of variability

management.

The average number of suppliers contributing to

a product is less than 3 at 16% of the respondents,

between 3 and 5 at 27%, between 6 and 9 at 16%,

between 10 and 15 at 15% and more than 15 at 26%

of the participating SME.

Reuse of components in new products or new vari-

ants of an existing product could be improved consid-

erably, according to the opinion of a majority of the

respondents. 26% state that currently there is no reuse

of components at all, 15% answer that there is nearly

no reuse. 26% answer that reuse happens sometimes,

20% state that reuse happens often, 13% very often.

On the question whether it would be possible to reuse

more, 16% respond ”definitively possible”, 48% ”yes,

probably” and 36% think it is not possible.

4.3 Document Management in Projects

The survey also included a number of questions on

projects performed in the enterprises. Main inten-

tion was to investigate the complexity of projects per-

formed and the documentation involved. The project

related questions were answered by 71 out of in total

113 SME participating in the survey. The following

part of the results is based on these 71 answers.

In order to get information about project complex-

ity, the survey included questions about the number

of project members, run time, number and volume of

project documents, structure and content of project-

related documents. Based on the respondents’ an-

swers, the projects in SME are rather small in terms of

project members. 39% state a project has only up to

3 members, 51% have between 4 and 8 members and

only 10% have more than 8 members. The large ma-

jority of the projects has a run time of more than one

month but less than one year: 39% state that the aver-

age project run time is between 1 and 4 months, 32%

have an average run time between 4 and 12 months.

Enterprises with average project length of less than

one month (20%) and more than one year length (9%)

are in the minority.

The number of documents produced in a project

varies considerably within the sample: 37% of the re-

spondents state that there are on average less than 10

documents, 35% between 11 and 25 documents, 13%

between 26 and 60, and 15% more than 60 documents

in a project.

Most of the documents are quite small in terms of

ICEIS 2008 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

108

number of pages. 51% state that the documents on

average have less than 4 pages and 37% between 4

and 10 pages. Only 10% of the respondents have an

average document size of between 11 and 25 pages,

3% between 26 and 50 pages.

Regarding the document structure, standardisation

seems to be common practise. In more than 85%, the

document structure is identical in different projects

(38%) or nearly identical (47%). 11% state that the

structure sometimes is similar. A not at all similar

structure in different projects can be found only at 4%

of the respondents.

5 DISCUSSION

The first conjecture addressed the need for support-

ing search and information retrieval in SME. Experi-

ences from using ontologies for structuring informa-

tion or within search engines show clearly that they

can contribute to improving precision. Examples for

investigation in this field can be found in (Ciravegna

and Petrelli, 2006) and (Redon et al., 2007). However,

the main question to discuss from an SME perspective

is which approach creates the best benefit/effort ratio,

i.e. substantial benefits at a reasonable price.

As a considerable part of SME neither have In-

tranets or DMS, and as even the established sys-

tems have improvement potential, these improve-

ments should be made first before starting on ontol-

ogy development.

Thus, our conclusion regarding use of ontologies

for supporting information management in SME is:

• the SME participating in our survey perceive di-

verse information management problems, like dif-

ficulties to find the right information, shortcom-

ings in the established IT-systems or information

overload. This presents an application field for

ontologies,

• the use of conventional technologies should be

given preference to ontologies when improving

information management in SME.

The second conjecture addressed the need for sup-

porting management of product configuration and

variation. The fact that 61 of 113 SME responded

to the questions regarding product variability in the

survey gives a first indication that many SME actu-

ally provide physical products consisting of various

parts. In section 2.2 the concept of product com-

plexity was briefly discussed including indicators for

product complexity. For the purpose of evaluating the

product complexity in the sample, we included four

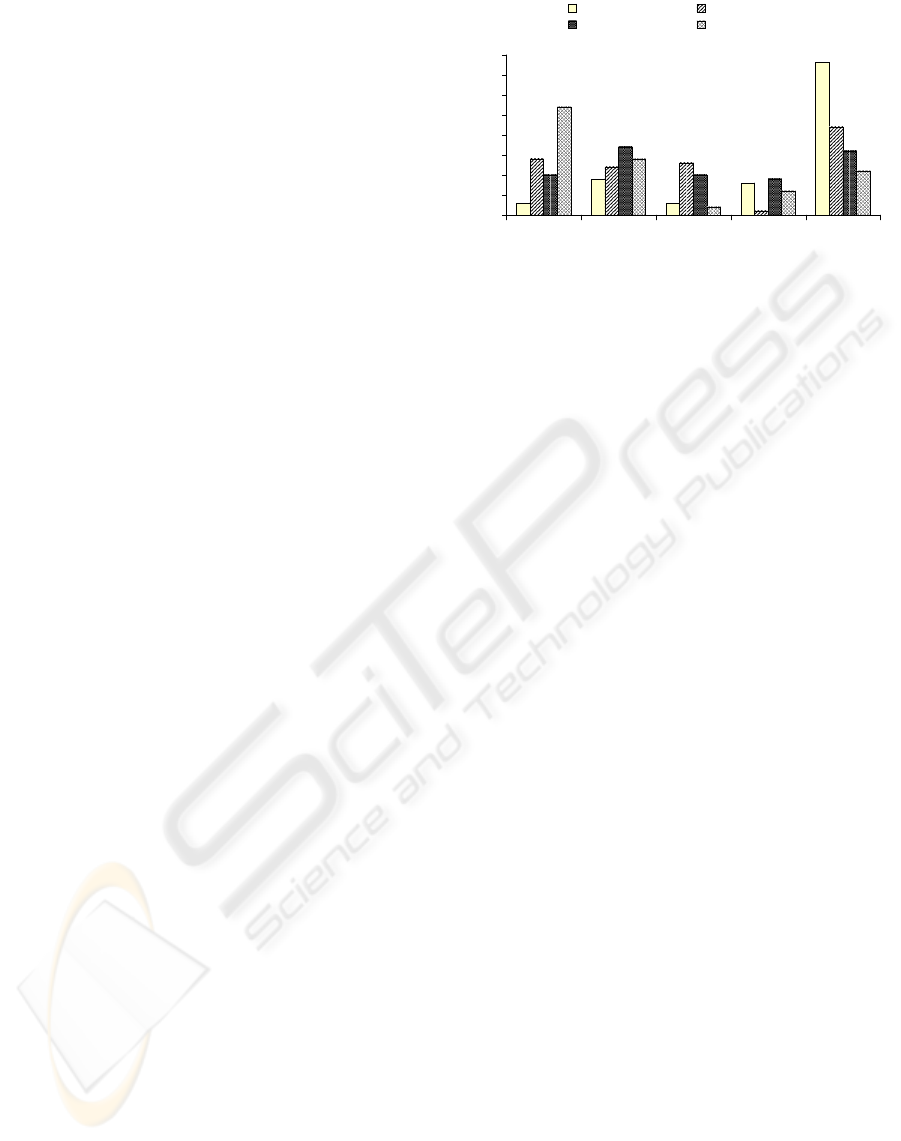

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

Very

Low

Low Medium High Very

High

Value

No of Products No of Components

No of Suppliers No of Variants

Figure 2: Distribution of very low to very high for the four

product-related criteria.

criteria, which are connected to four questions in the

survey:

• number of products,

• average number of components per product,

• average number of suppliers per product,

• number of variants.

These four criteria match directly to the indica-

tors proposed by Baccarini and Hobday (see 2.2). For

each of these four criteria, the survey questions of-

fered five different choices. Mapping these choices on

a scale from ”low” to ”very high”, i.e. the choice with

the lowest number of products, components, variants

and suppliers is mapped to ”low” and the choice with

the highest number is mapped to ”very high”, helps to

visualise the distribution of the answers regarding the

four criteria. Figure 2 shows this distribution.

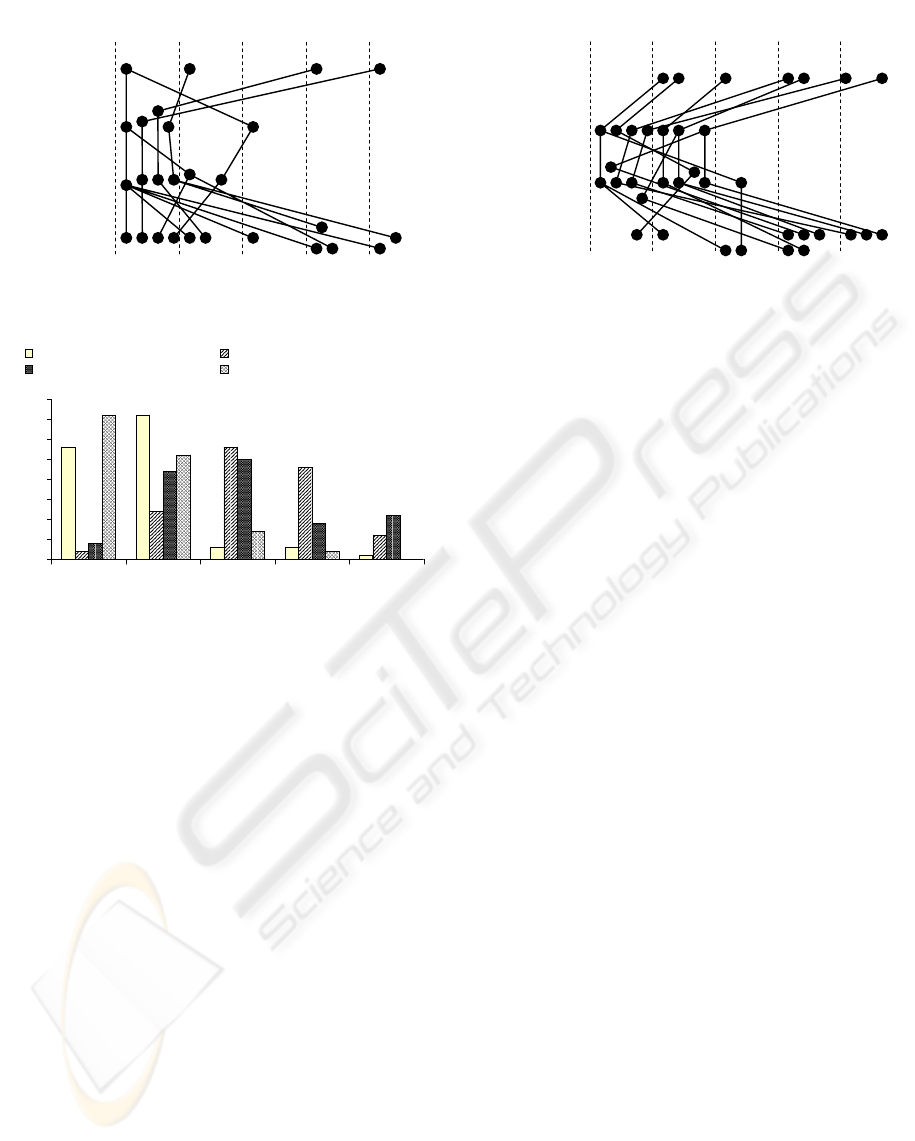

Furthermore, it is important to know whether there

is a correlation between the four criteria, for exam-

ple whether companies with a high number of prod-

ucts also have a high number of variants and many

suppliers. When investigating this aspect, we found

31 cases with at least two criteria receiving at least

”high”. Of these 31 cases were 21 with two times

”very high” and 16 with three times at least ”high”.

Figure 3 visualises these 16 cases.

In terms of complexity, we consider at least the 16

cases shown in figure 3 as complex enough to seri-

ously investigate the use of ontologies. The 16 cases

show both, a very high degree of differentiation and

interdependencies between the criteria. Even for the

other 15 cases, who at least receives two times ”high”

or ”very high”, we see development potentials for on-

tologies, as all of them at least have one criteria on

”medium” level, which contributes to substantial dif-

ferentiation and interdependencies.

Based on the above discussion, we conclude that

there is a need for supporting variability management.

Approximately a quarter of all SME in the sample

DO SME NEED ONTOLOGIES? - Results from a Survey among Small and Medium-sized Enterprises

109

No. products

No. components

No. suppliers

No. variants

Very

High

High

Medium Low

Very

Low

2

2

2

2

Figure 3: Cases from the survey with highest product com-

plexity.

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

Very

Low

Low Medium High Very

High

Value

No of Employees Time Range

No of Documents No of Pages in Each Document

Figure 4: Distribution of very low to very high for the four

project document management-related criteria.

and more than half of those SME answering the prod-

uct related questions have a substantial complexity in

their product portfolio.

Conjecture 3 focused on the need for supporting

document management in project work. 71 of 113

SME responded to the questions regarding project

work, which indicates that many SME actually use

project organisation based on documents. Evaluating

the complexity of document management in projects

again included four criteria, which are connected to

questions in the survey:

• average number of employees in a project,

• average number of documents per project,

• average duration of projects,

• average number of pages per documents.

The first two criteria directly relate to Baccarini’s

work (see 2.2); the other two were derived in order to

represent document complexity. The survey questions

offered five different choices for each of these four

criteria, which were mapped on a scale from ”low” to

”very high”. Figure 4 visualises the distribution of the

answers regarding the four criteria.

No. employees

Time range

No. documents

Pages in each

document

Very

High

High

Medium Low

Very

Low

2

Figure 5: Cases from the survey with highest project docu-

ment management complexity.

Considering the correlation between the four cri-

teria, we found 13 cases with at least two criteria re-

ceiving at least ”high”. Of these 13 cases were 5 with

two times ”very high”. Figure 5 visualises these 13

cases.

In terms of complexity, we consider at least the 13

cases shown in figure 5 as complex enough to seri-

ously investigate the use of ontologies. These cases

show both, a very high degree of differentiation and

interdependencies between the criteria. Comparing

these figures with the situation in product complex-

ity (conjecture 2), the significance of a need for sup-

porting project document management is not as high.

However, 18% of the SME working in project organ-

isation and 11% of all SME in the sample show a

high complexity, which from our perspectives is suf-

ficient motivation to aim at supporting project docu-

ment management.

6 CONCLUSIONS

The main purpose of this paper is to contribute to re-

search on ontology development methods by investi-

gating, which application areas for ontologies in SME

could motivate the development of specialised ontol-

ogy construction methods. The performed survey was

guided by five conjectures intended to help in identi-

fying such areas, which can be used to summarise the

conclusions.

• There is a need for supporting information search-

ing: the survey results clearly confirmed this con-

jecture. However, existing tools like DMS could

be used to support these needs.

• There is a need for supporting management of

configurations or variations of products: again,

the survey results clearly supported this conjec-

ture.

ICEIS 2008 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

110

• There is a need for structuring documents and

support of document management: the survey re-

sults supported this conjecture, but not to the same

extent as in the first two conjectures.

• There exists a need for supporting collaboration

and interoperability in networks of companies:

this conjecture was not included in the survey,

as the interviews performed prior to the study

indicated significant problems in capturing suffi-

ciently detailed information with ontologies.

• There is a need for capturing enterprise knowl-

edge: again, this conjecture was not further in-

vestigated after the interviews, as big concerns

were expressed that capturing personal knowl-

edge would be feasible.

Thus, the conclusion from the survey is that SME

need ontologies mainly in the area of product con-

figuration and variability modelling. This application

area will be given highest priority when developing a

purpose-oriented ontology construction method. The

application area with the second highest priority is

document management for supporting project work.

This area can be seen as a sub-area of information

search and retrieval with specific focus on project sup-

port.

Regarding the last two conjectures, we received

a number of indications in the interviews and even

within the survey, that application potential of ontolo-

gies could exist for capturing knowledge in SME and

for supporting supply chains. However, this is not per-

ceived as a priority area by the SME and will thus

have the lowest priority in future work.

The main limitations of the survey are:

• the survey only included SME from a geographi-

cally limited area, which is the south of Sweden,

• the majority of SME participating in the survey

were manufacturing companies,

• the size of the sample was not large enough for

achieving results of statistical significance.

These limitations should be taken into account

when investigating whether the results are transfer-

able to other areas or applicable in other research con-

texts.

REFERENCES

Baccarini, D. (1996). The concept of project complexity - a

review. International Journal of Project Management,

14:201–204.

Blomqvist, E.,

¨

Ohgren, A., and Sandkuhl, K. (2006). On-

tology Construction in an Enterprise Context: Com-

paring and Evaluating Two Approaches. In Proc. of

the 8th International Conference on Enterprise Infor-

mation Systems.

Ciravegna, F. and Petrelli, D. (2006). Annotating document

content: a knowledge management perspective. Inter-

national Journal of Indexing, 24(5).

Hobday, M. (1998). Product Complexity, Innovation and

Industrial Organisation. Research Policy, 26:689–710.

Koellinger, P. (2006). Impact of ICT on Corporate Perfor-

mance, Productivity and Employment Dynamics. The

European E-business Market Watch. Special Report

No. 01/2006.

Lau, T. and Sure, Y. (2002). Introducing Ontology-based

Skills Management at a Language Insurance Com-

pany. In Modellierung in der Praxis - Modellierung

fr die Praxis, volume 12 of LNI.

Levy, M., Powell, P., and Yetton, P. (2002). The Dynam-

ics odf SME Information Systems. In Small Business

Economics, Vol. 19, No. 4.

Lybaert, N. (1998). The Information Use in a SME: Its

Importance and Some Elements of Influence. Small

Business Economics, 10(2).

McGuinness, D. L. (2002). Ontologies Come of Age. In

Spinning the Semantic Web: Bringing the World Wide

Web to Its Full Potential. MIT Press.

Obitko, M. (2001). Ontologies - Description and Applica-

tions. Technical report, Gerstner Laboratory for Intel-

ligent Decision Making and Control, Czech Technical

University in Prague.

¨

Ohgren, A. and Sandkuhl, K. (2005). Towards a Methodol-

ogy for Ontology Development in Small and Medium-

Sized Enterprises. In IADIS Conference on Applied

Computing, Algarve, Portugal.

Ontoweb (2004). Ontology-based information ex-

change for knowledge management and elec-

tronic commerce. Downloaded from http://

www.ontoweb.org/download/deliverables/ 2004-

10-05.

Redon, R., Larsson, A., Leblond, R., and Longueville, B.

(2007). Vivace context based search platform. In

CONTEXT07, volume 4635 of LNCS (LNAI), pages

397–410. Springer, Heidelberg.

Sandkuhl, K. and Billig, A. (2007). Ontology-based Arte-

fact Management in Automotive Electronics. Interna-

tional Journal for Computer Integrated Manufactur-

ing (IJCIM), 20(7):627–638.

Uschold, M. and Gruninger, M. (1996). Ontologies: Prin-

ciples, Methods, and Applications. Knowledge Engi-

neering Review, 11(2), 93–155.

DO SME NEED ONTOLOGIES? - Results from a Survey among Small and Medium-sized Enterprises

111