Which Comes First e-HRM or SHRM?

Janet H. Marler

1

and Emma Parry

2

1

The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania

2

Cranfield School of Management

Abstract. There has been some discussion in the literature of the relationship

between e-HRM and strategic HRM. One body of literature argued that the use

of e-HRM leads to a more strategic role for the HR function by freeing time and

providing accurate information for HR practitioners [1,2]. An alternative

argument is that e-HRM is the result of a strategic HR orientation in that it is

one means by which SHR can be practiced [3,4]. This study disentangled these

two arguments by using data from a large international HR survey. The results

showed that e-HRM does not appear to be the linking mechanism that results in

companies with HR strategies becoming more involved in setting business

strategy, but instead that e-HRM and strategic involvement are related

indirectly based on its relationship to a company’s HR strategy.

1 Introduction

Past literature has provided two explanations of the relationship between e-HRM and

strategic HRM. A number of authors have suggested that e-HRM can act as a cause

of strategic HRM (SHRM) through the freeing up of HR practitioners’ time and the

provision of high quality information that enables them to act more strategically. The

alternative view, situated in the literature on contingent strategic HRM, suggests that

this relationship is reversed, in that e-HRM is a result of the strategic orientation of

the HR function. This view suggests that e-HRM is used as a part of SHRM to

achieve the competitive goals of the organization. To date, scholars have not

attempted to disentangle these two arguments by examining them simultaneously.

This paper will address this gap by addressing the question – which comes first: e-

HRM or SHRM? In laying the ground work for our discussion we distinguish

between SHRM and HR strategy. We therefore do not use these constructs

interchangeably but rather treat them as different and distinct.

Peruse the websites of various e-HRM software vendors and inevitably there will

be a customer statement describing how implementing an e-HRM product enhances

the HR function’s ability to be more strategic. The implication is that by combining

web-based information technology with human resource functionality, the HR

function is transformed from a transaction-burdened paper processor to a valued

strategic partner. The need for the HR function to transform to a function that is more

strategic has received significant attention in the literature for many years. Legge [5]

noted that the HR function should be more involved in senior management decision-

making and both Ulrich [6] and Paauwe [7] suggested that HR needed to become

H. Marler J. and Parry E. (2008).

Which Comes First e-HRM or SHRM?.

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop on Human Resource Information Systems, pages 40-50

DOI: 10.5220/0001731600400050

Copyright

c

SciTePress

“more business oriented, more strategic and more oriented towards organizational

change”. A series of academics have set out the theoretical and empirical background

to the proposition that HR practitioners can have strategic impact [8, 9, 10]. The key

notion here is that the HR function is included in formulating and implementing

business strategy and hence is considered strategic.

Several scholars reinforce the claim that using e-HRM may help to transform the

HR function into a strategic business partner. For instance, Bussler and Davis [11]

concluded that “with the use of technological solutions, HR is no longer transactional

and reactionary but strategic and proactive” (p.17). Snell et al [12] provided a

detailed case study example of IT’s ability to provide “transformational impact” by

leading to “fundamental changes in the scope and function of the HR department”.

This supported the suggestion that this transformation of HR was perhaps the most

dramatic impact of IT [2]. Shrivastava and Shaw [13] also suggested that e-HRM

could have a transformational impact on the HR function by redefining its scope and

allowing it to focus on more strategic activities.

Authors have suggested that e-HRM can facilitate this transformation in the role

of HR to one that is more strategic in two main ways. Firstly, the use of automated or

self-service systems to accomplish a great deal of HR’s transactional or administrative

work means that the HR function has more time to manage human resources

strategically and become a full partner in the business [14,15]. Secondly, the use of e-

HRM means that detailed information about a company’s people can be produced

quickly and easily. This data can be used for analytical decision support [16] and to

drive strategic organizational decisions [17].

In one of few empirical studies, Parry and Tyson’s [1] qualitative study of ten UK

organizations showed how the implementation of a web-based human resource

information system could lead to a shift towards more strategic activities in the HR

department. Parry and Tyson’s study found that the use of e-HRM could indeed

provide HR practitioners with the time and information in order to act more

strategically. Lawler and Mohrman [18] also supported this proposition through their

longitudinal survey of HR leaders. They found that advanced IT based systems can

both offload transactional tasks, freeing up HR professionals for more value-added

roles and offer the potential for HR to collect and analyze data on the effectiveness of

various approaches and decisions.

As a contrast to the above claims, however, strategic HRM scholars depict e-HRM

as the end result of strategic HRM. SHRM has been defined as “the pattern of planned

human resource deployments and activities intended to enable the firm to achieve its

goals” [10]. Wright and McMahan go on to state that the two most important

dimensions of SHRM are “the linking of HRM practices with the strategic

management process of the organization” and the “coordination among the various

HRM practices through a pattern of planned action” (p. 298). HR strategy represents

the “linking” mechanism between strategic formulation and implementation. Martin-

Alcazar et al [19] define HR strategy as an integrated set of human resource

management policies and practices developed to support execution of the company’s

implicit or explicit business strategy through managing the firm’s human capital.

Boxall and Purcell [9] explain that SHRM as a field of study is concerned with the

strategic choices associated with the use of labour in firms and with “explaining why

some firms manage them more effectively than others” (p. 49). By these definitions,

the use of e-HRM may be seen as a strategic choice, in itself as a way of enabling an

41

organization to achieve its goals and can, therefore, be an outcome of SHRM rather

than the driver of a strategic HR role.

Broderick and Boudreau [4] supported this idea with their use of Schuler and

Jackson’s [20] contingent SHRM model to explain how information technology may

be used in different ways as a result of the firm’s competitive strategy. Schuler and

Jackson [20] created a framework for external fit in SHRM based on Porter’s [21]

suggestion that firms should specialize in one of cost leadership, differentiation or

focus. Schuler and Jackson [20] argued that business performance will improve when

a firm’s HR practices mutually reinforce the firm’s choice of the competitive strategy

of cost leadership, quality and customer satisfaction and innovation. Different

strategies require different kinds of employee behaviour, and therefore different HR

practices to encourage these behaviours. Broderick and Boudreau [4] explained how

transaction processing systems, expert systems and decision support systems could be

used to achieve the objectives of Schuler and Jackson’s three competitive strategies.

For example, transaction processing systems could be used to support customer

satisfaction/quality strategies by increasing the time for quality initiatives, enabling

custom reports and increasing the awareness of HR information. This suggestion

supports the assertion that e-HRM is an outcome of SHRM rather than a cause.

Reddington and Martin [3] also suggested a model by which the goals of e-HRM

systems are driven by HR strategy and HR policies. These goals can be classified in

terms of transactional goals such as reducing costs and HR headcount and

transformational goals such as freeing up the time of HR staff to address more

strategic issues, and by transforming the contributions that HR can provide to the

organization. This model therefore supports the idea that the use of e-HRM is a result

(rather than a cause) of the strategic nature of the HR function. Hannon et al [22]

suggested that human resource information systems have the potential to be the

mechanism by which transnational organizations monitor and deploy their personnel

in order to attain and sustain a competitive advantage. Ruel et al [23] have found that

e-HRM can be used to promote the effectiveness of HRM therefore laying more

weight to this argument.

We can see from the above discussion therefore that there are opposing views of

the relationship between SHRM and e-HRM. In one view e-HRM precedes the HR

function becoming more strategic, either as the process by which HR strategies

becomes strategic as illustrated in Figure 1 or the catalyst as illustrated in Figure 2.

Fig. 1. e-HRM is the process by which HR Strategy makes HR more strategic.

In Figure 1, e-HRM is the result of HR strategy but is also the linking mechanism

between HR strategy and Strategic HRM. As an the integrated set of human resource

management policies and practices developed to support execution of the company’s

implicit or explicit business strategy through managing the firm’s human capital [19],

e-HRM then represents a strategic choice regarding how to best implement or deliver

these practices. By enabling the successful delivery of relevant human resource

practices, e-HRM then facilitates elevating the role of HR from administrative

transaction processor to strategic business partner. Thus our first set of hypotheses

HR strategy e-HRM

HR role in

Business Strate

gy

42

articulate the direction of these relationships in which e-HRM represents the process

by which HR strategy realizes its strategic role within an organization.

H1: The relationship between HR strategy and HR involvement in business strategy

is mediated by stage of e-HRM such that the stage of e-HRM implementation is the

process through which HR strategy is related to HR involvement in business strategy.

Fig. 2. HR Strategy is the process by which e-HRM makes HR more strategic.

The alternate relationships in Figure 2 illustrates a slightly different view in which

investments in e-HRM free up time for HR to focus on more strategic activities.

Through spending more time on strategic value added activities HR builds an HR

strategy and through these strategic activities, HR also develops credibility to take on

a more active role in the creation of business strategy. The following hypotheses

reflect this possible relationship:

H2. The relationship between stage of e-HRM and HR involvement in business

strategy is mediated by HR strategy such that creating an HR strategy is the process

through which e-HRM is related to HR involvement in business strategy

development.

Fig. 3. HR Strategy is the process by which e-HRM is strategic.

Finally, in Figure 3, e-HRM is the consequence of a rational set of decisions

emanating from the top of the organization. This represents the more

traditional/contingent view of strategic human resources in which involvement in

business strategy precedes the development of an HR strategy and that e-HRM

evolves out of best implementing the HR strategy. Thus the last hypothesis proposes

the third alternative set of relationships:

H3: The relationship between HR involvement in business strategy and the stage of

e-HRM in a firm is mediated by HR Strategy.

Which view is more accurate? In this paper we, empirically examine this question

using an international data set comprising over 3,500 companies located in 29

different countries.

2 Methods

2.1 Sample and Procedures

The data used in this study were taken from the 2003 Cranet survey, by far the most

comprehensive international survey of HR policies and practices at the organisational

e-HRM

HR strategy

HR role in

Business Strategy

HR role in

Business Strategy

HR strategy

e-HRM

43

level. Cranet is a regular comparative survey of organisational policies and practices

across the world conducted by a network of business schools operating in 40 countries.

The unit of analysis is the organisation and the respondent is the highest-ranking

corporate officer in charge of HRM. The 2003 questionnaire was developed using an

iterative process between network members and based on previous experience of

running survey rounds since 1990.

Respondents in each country were identified via the use of a database of senior

HR managers in public and private sector organisations. The data was approximately

representative for the population of each country in terms of industry sector and

organisation size. Representing 7,914 companies, these data cover a wide range of

countries and HR policies and practices. The data were collected over an eighteen-

month period from late 2003 until mid 2005. The response rate across countries

ranged from 5% to 86%.

In this study only companies with self-reported human resource information

systems were analyzed. Thus out of a total sample of 7,914 companies, the final

useable sample consisted of 3,747 companies from 29 countries. These companies

represented those companies for which there were no missing data or reasonably

imputable data for the variables measured in this study. Most of the missing data

arose either because company headquarter information was not completed or where

the company indicated they had no human resource information system. In the later

case, respondents were then directed to skip questions related to e-HRM. To

determine whether such missing data were a concern we reran our analyses assuming

a zero value for stage of e-HRM for all missing data responses. Our results were

similar to the results we report here.

2.2 Measures

The three dependent and independent variables for this study were whether the

organization had an HR strategy, at what stage the organization was in it’s e-HRM

capability, and the HR function’s involvement in the organization’s business strategy.

These variables were measured using responses from the Cranet questionnaire.

HR Strategy was measured as a one-item scale representing a self-reported

response to the following question, “Does your organization have a personnel/HRM

strategy?” Response choices were: 1= yes, written; 2 = yes, unwritten; 4 = no, and 3=

don’t know. The variable was treated as ordinal and reversed-coded.

e-HRM Stage represented a one-item scale in which the respondent indicated at

which stage they believed their level of HR web deployment was. Response choices

described 5 levels in which the lowest level was described as one-way communication

(e.g information publishing for general scrutiny). The middle level was two-way

communication: employee is able to update simple personal information such as bank

details. The highest level represented a system that allowed more complex

transactions than two communications which included selection, calculation and

confirmation by and for employees.

HR Involvement in Strategy was measured as one-item scale in which the

respondent chose at which stage the person responsible for personnel/HR was

involved in the development of the organization’s business strategy. The four

response options were: 1= from the outset, 2=through subsequent consultation, 3= on

44

implementation and 4 = not consulted. This scale was treated as ordinal and was

reversed-coded.

In addition to the dependent and independent variables of interest, we also

included several control variables that might also be associated with the use of e-

HRM, the existence of an HR Strategy or HR involvement in an organization’s

strategy to reduce omitted variable bias. These control variables consisted of

measures of whether the company outsourced its human resource information system,

outsourced other HR functions, the location of the company’s headquarters, whether

the company’s main product market was local, proportion of employees that were

members of a trade union, size, and industry.

Measures of HRIS Outsourcing and HR Outsourcing were created from responses

to a question on how had the company’s use of external providers for payroll,

pensions, benefits, training and development, workforce outplacement, and HR

information systems had changed. Response choices comprised an ordinal measure

beginning with external providers not used, decreased, same, and ending with

increased. The measure for HRIS outsourcing represented a dichotomous measure

where one indicated use of an external provider, whether decreased, increased or

remained the same, and zero indicated the company did not use an external provider.

The measure of HR Outsourcing was derived by adding the responses for whether

external providers were used for payroll, pensions, benefits, training and development,

and workforce outplacement. The highest score was obtained if a company indicated

that they had increased external provider use for all five HR services. The lowest

score would represent those companies that did not use external providers for any of

the five HR services.

Percent union represented the proportion of the total number of employees in the

company that were members of a trade union. Size was measured as the natural

logarithm of the total number of people employed in the company

Indicator variables were created for the location of each company’s corporate

headquarters, product market and industry. Five dummies indicated if the

headquarters were in the European Union, Europe outside of the EU, North America,

South-East Asia, or Africa. The indicator for product market indicated if the

company’s main products or markets were local or else zero if mainly national,

European of world-wide. Finally dummy variables for 14 self-reported industry

sectors were also created. Where necessary, the omitted or reference industry category

were the banking, finance and insurance industry.

2.3 Analysis

The key variables in this study are company-level variables nested in countries, which

makes these data hierarchical. Consequently we adopted hierarchical linear modeling

to test our hypotheses. In mean centering the company level data and using

hierarchical linear modeling, we were able to estimate the company-level

relationships net of any country-level effects [24]. Thus all the coefficients

represented an efficient estimate of company relationships using the full sample of

companies.

We performed our analyses in three steps following similar procedures outlined

by Bryk and Rudenbush [24], (200 First we estimated a null model in which there

45

were no predictors at either level 1 (company level) or level 2 (country level) to

partition the dependent variables (HR Strategy, e-HRM and HR Strategic

Involvement) into within- and between-country components. From this information

we computed the proportion of the total variance around the grand mean of each

dependent variable related to company-level variance and variance related to country-

level effects. Second, in the level 1 analyses, the dependent variables were regressed

on country-mean-centered company-level predictors and control variables. A

regression line was estimated for each of the 29 countries in this step. In the third step,

which represented the level 2 analyses, the intercepts and beta coefficients estimated

in the step 2 regressions were tested to see if they varied significantly across countries

.

3 Results

The average company in our sample had approximately 2,400 employees with about

26-50% being members of a trade union. On average, our sample companies had an

HR strategy but it was unwritten, therefore, more informal. Further the person

responsible for HR was, on average, was not a strategic business partner and was only

involved in developing the business strategy through subsequent consultation.

Outsourcing payroll related functions was also the norm. On average a company

outsourced at least 3 other HR functions such as payroll, pensions, and benefits.

Furthermore, 80% of sample outsourced HRIS. Not surprisingly, therefore, as of 2003,

the companies were on average at stage 1 of e-HRM deployment with only about 15%

at more sophisticated stages of

deployment (Stage 4 and Stage 5).

Our data analyses reveal that across the three dependent variables, E-HRM stage,

HR involvement in business strategy, and HR strategy, between country variations

was quite limited. For e-HRM it represented 7.5% of the total variance in e-HRM

shown on Table 2 column 1; for HR involvement and HR strategy it only represented

9% of the variance on Table 3 column 1 and Table 4 column 1, respectively. Thus

most of the variance in these variables occurred between companies not between

countries.

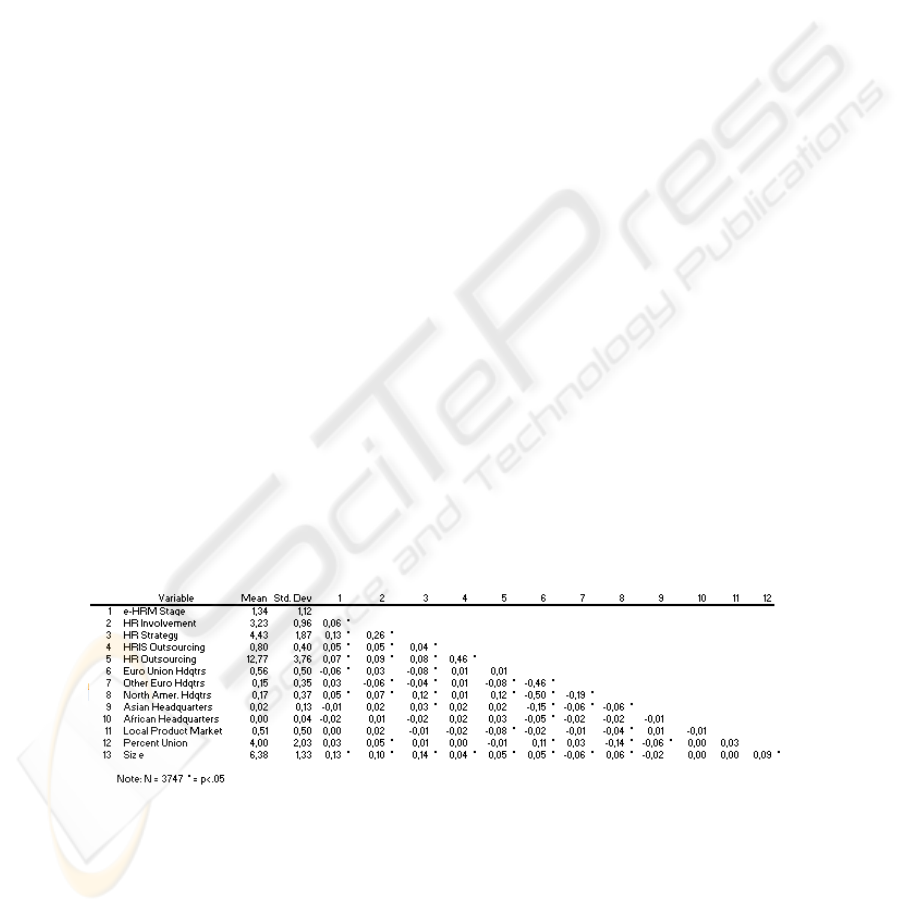

Table 1. Variable Means and Correlations.

46

Table 2. Hierarchical Linear Modeling Results for e-HRM Stage.

Variable

τ

123 4

Level 1

Intercept 1,39 (0,06) *** 1,70 (0,11) *** 1,57 (0,09) *** 1,56 (0,11) ***

HRIS Outsourcing -0,11 (0,06) * 0,07 (0,06) 0,08 (0,06)

HR Outsourcing 0,02 (0,01) ** 0,02 (0,01) ** 0,02 (0,01) ***

Euro Headquarters -0,05 (0,06) -0,06 (0,06) -0,06 (0,06)

Asian Headquarters -0,07 (0,12) -0,09 (0,12) -0,09 (0,11)

African Headquarters -0,29 (0,09) *** -0,35 (0,07) *** -0,30 (0,10) **

Local Product Market -0,03 (0,04) -0,03 (0,04) -0,02 (0,04)

Percent Union -0,01 (0,01) -0,01 (0,01) -0,01 (0,01)

Size 0,10 (0,02) *** 0,10 (0,02) *** 0,09 (0,02) ***

e-HRM Stage

HR Involvement 0,04 (0,02) * 0,02 (0,02)

HR Strategy 0,10 (0,02) *** 0,06 (0,01) ***

Level 2

Intercept 1,56 (0,1) *** 0,1 ***

e-HRM Stage

HR Involvement 0,00 (0,0) 0,0 *

HR Strategy 0,06 (0,0) *** 0,0

Between-Country residual 0,093

Within-Country residual

variance

1,156 1,11 1,11 1,10 1,10

Between-country variance 0,075

R2 within-country 0,04 0,04 0,05 0,05

Model deviance

ni 3753

nj 29

e-HRM

Company-LevelNull Model Company-Level Country-Level

Table 3. Hierarchical Linear Modeling Results for HR Involvement in Business Strategy.

Variable Company Level Country Level

τ

123

Level 1

Intercept 4.50 -0.11 **** 3.09 (0.07) *** 3.08 (0.07) ***

HRIS Outsourcing -0.01 (0.04) 0.00 (0.04)

HR Outsourcing 0.02 (0.00) *** 0.01 (0.00) ***

Euro Headquarters -0.13 (0.08) + -0.11 (0.07)

Asian Headquarters 0.19 (0.07) * 0.18 (0.08) *

African Headquarters 0.17 (0.21) 0.26 (0.14) +

Local Product Market 0.03 (0.04) 0.04 (0.04)

Percent Union 0.01 (0.01) 0.01 (0.01)

Size 0.05 0.01 *** 0.02 (0.01) +

e-HRM Stage 0.03 (0.02) * 0.01 (0.02)

HR Strategy 0.13 (0.01) ***

Level 2

Intercept 3.07 (0.07) *** 0.06 ***

e-HRM Stage 0.01 (0.02) 0.00 *

HR Strategy 0.13 (0.01) *** 0.00 ***

Between-Country residual 0.32 *** 0.05

Within-Country residual variance

3.19 0.86 0.81 0.805

R2 within-country 0.7 0.74 0.75

Between variance 0.09

Model deviance 15053

ni 3753

nj 29

Includes but not shown 14 industry fixed effects. The comparison/excluded industry is banking and financial services.

HR Involvement in Business Strategy

Null Model

In testing Hypothesis 1 in which we proposed that e-HRM mediated the

relationship between HR strategy and HR involvement in business strategy, we

followed the standard tests for mediation. We first regressed HR strategy on HR

involvement shown on Table 2 column 3 and then regressed HR strategy on e-HRM

shown on Table 4 column 3. We then regressed both HR strategy and e-HRM on HR

involvement. Our results shown on Table 2 column 6 and indicate that there is no

support for Hypothesis 1. The parameter estimate for e-HRM is not significantly

related to HR involvement.

We followed the same steps for testing Hypothesis 2 and Hypothesis 3. Our results

shown on Table 3 columns 2 and 4 provide support of Hypothesis 2. When e-HRM

47

stage is regressed on HR involvement without controlling for HR strategy there is a

significant relationship (b=.03 p<.05). However, when HR strategy is added to the

model, e-HRM loses significance but HR strategy remains significant (b = .13

p<.001).

Our results also support Hypothesis 3 in which we propose the more traditional

strategic human resource causal specification. Here the relationship runs in the

opposite to the one posited in Hypothesis 2. Our results indicate that HR

involvement’s in business strategy significantly predicts stage of e-HRM shown on

Table 2 column 4 (b = .04 p<.05) and so does HR strategy shown on Table 2 column

2 (b = .10 p<.001). When both variables are entered together, however, HR

involvement is no longer a significant predictor of e-HRM but HR strategy remains

significant (b=.06 p<.001).

Table 4. Hierarchical Linear Modeling Results for HR Strategy.

Variable

τ

12

Level 1

Intercept 4.49 (0.1) *** 4.71 (0.14) ***

HRIS Outsourcing -0.07 (0.06) ***

HR Outsourcing 0.01 (0.01)

Euro Headquarters -0.01 (0.01)

Asian Headquarters 0.08 (0.19) ***

African Headquarters -0.77 (0.51)

Local Product Market -0.11 (0.08)

Percent Union -0.03 (0.02)

Size 0.18 (0.03) ***

e-HRM Stage 0.16 (0.02) ***

HR Involvement 0.45 (0.03) ***

HR Strategy

Level 2

Intercept 4.70 (0.15) *** 0.33 ***

e-HRM Stage 0.16 (0.03) *** 0.00

HR Involvement 0.43 (0.03) *** 0.01

HR Strategy

Between-Country residual 0.32

Within-Country residual

variance

3.19 2.88 2.88

Between-country variance 0.09

R2 within-country 0.10 0.10

Model deviance 11697 14718 14712

ni 3753

HR Strategy

Null Model Company-Level Country-Level

4 Discussion

We add to the literature on the role e-HRM plays in the strategic HR landscape

through the use of data from a large scale quantitative survey. We use this

quantitative data to examine the relationship between stage of e-HRM investment and

its relationship with making HR “more strategic”. We distinguish between two

concepts in the literature on HR and strategy. First, we identify the concept of an HR

strategy, which we defined as representing HR policies and practices aimed at

supporting the business strategy. Second we considered to what extent HR was

involved in setting the company’s business strategy. We have used the latter variable

to reflect the existence of strategic HRM, where the HR function is viewed as a

strategic business partner in overall strategy development. Our results provide a

number of insights into the relationship between e-HRM, HR strategy, and strategic

HRM.

Firstly, our results show that stage of e-HRM is not the “process” through which a

company’s HR strategy transforms the HR function into becoming a business partner

48

(hypothesis 1). Thus, e-HRM does not appear to be the linking mechanism between

HR strategy and elevating the HR function into a strategic business partner.

Our results, however, suggest the relationship between e-HRM and strategic HRM

operates indirectly through the company’s HR strategy. Thus our results provide

support for the second and third hypotheses. With cross sectional data, however, we

cannot say whether e-HRM precedes having an HR strategy or it follows having an

HR strategy. Does a firm invest in e-HRM and this makes HR strategic which in turn

is related to greater HR involvement in setting business strategy? Or do companies in

which HR is involved in business strategy create HR strategies which facilitate

investing in e-HRM? In the former, e-HRM precedes transformation to SHRM

through its relationship with HR strategy. In this specification e-HRM precedes both

HR strategy and SHRM. In the latter, e-HRM is the result of HR being a SHRM

function first.

The endogenous relationship between e-HRM and HR strategy can arise for two

reasons. First, the reciprocal relationship may be spurious in that it is really the result

of both being related to a common third factor. We tried to rule out this possibility by

including other variables, such as HR outsourcing, size, and location in our model

specification. A second reason for reciprocity might arise from causal ordering. One

variable precedes the other but the relationship is also circular. To address this

possibility involves conducting research with longitudinal data. In this way we can

examine the order in which the relationships unfold.

Qualitative case studies can also shed light on this sequencing puzzle. The evidence

provided by Parry and Tyson [1] suggests that the causal order is best represented in

Figure 2 rather than Figure 3. That is initially, e-HRM precedes the development of a

HR strategy which in turn leads to HR’s greater involvement in business strategy

development. Parry and Tyson’s case studies also suggest however, that in some cases,

the implementation of e-HRM may be the result of an HR strategy that reflects

increased involvement of HR in business strategy, thus also lending support to Figure

3. It is clear therefore that future research, both qualitative and quantitative in nature,

is needed to confirm whether these initial findings are true and also the contextual

contingencies that may better predict the causal ordering (e.g. e-HRM may precede

HR strategy in younger firms, in less developed countries, in certain industries, but

not mature companies, or in more developed countries, or certain industries).

Our examination makes an incremental contribution towards better understanding

the relationship between the use of e-HRM within organizations and the strategic

nature of the HR function. We establish the nature of this relationship, ruling out one

set of possible relationships but still leaving open the viability of two other sets of

relationships. Both qualitative and quantitative longitudinal research and more

comprehensive measures of key constructs are needed to build our knowledge of

where and when e-HRM contributes to strategic HRM.

References

1. Parry, E., Tyson, S.: (2006). The Impact Of Technological Systems on the HR Role: Does

the use of Technology Enable the HR Function to Become a Strategic Business Partner.

49

Paper Presented at the First Academic Workshop on Electronic Human Resource

Management (2006)

2. Lepak, D., Snell, D.: Virtual HR: Strategic Human Resource Management in the 21

st

Century. Human Resource Management Review. 8 (1998) 215–234

3. Reddington, M., Martin, G.: Theorizing the Links Between E-HR and Strategic HRM: a

Framework, Case Illustration and come Reflections, Paper Presented at The First Academic

Workshop on Electronic Human Resource Management (2006)

4. Broderick, R., Boudreau, J.: Human Resource Management, Information Technology and

the Competitive Edge. The Executive. 6 (1992) 7–17

5. Legge, K.: Human Resource Management: Rhetorics and Realities, Macmillan,

Basingstoke (1995)

6. Ulrich, D.: A New Mandate for Human Resources, Harvard Business Review. 76 (1998)

124–134

7. Paauwe, J.: HRM and Performance: Achieving Long Term Viability, Oxford University

Press UK (2004)

8. Becker, B., Huselid, M.: Strategic Human Resources Management: Where do we go from

here. Journal of Management. 32 (2006) 898–925

9. Boxall, P., Purcell, J.: Strategy and Human Resource Management, Palgrave Macmillan,

Basingstoke (2003)

10. Wright, P., Mcmahan, G.: Theoretical Perspectives for Strategic Human Resource

Management, Journal of Management. 18 (1992) 295–320.

11. Bussler, L., Davis, E.: Information Systems: The Quiet Revolution in Human Resource

Management. Journal of Computer Information Systems. 42 (2002) 17–20

12. Snell, S., Stueber, D., Lepak, D.: Virtual HR Departments: Getting out of the Middle, in R.

L. Heneman., D. B. Greenberger. (eds.): Human Resource Management in Virtual

Organisations, Information Age Publishing, Greenwich CT. (1992) 81–101

13. Shrivastava, S., Shaw, J.: Liberating HR through Technology, Human Resource

Management. 42 (2003) 201–222

14. Groe, G., Pyle, W., Jamrog, J.: Information Technology and HR. Human Resource

Planning. 19 (1996) 56–61

15. Panayotopoulou, L.; Vakola, M., Galanaki, E.: E-HR Adoptions and the Role of HRM:

Evidence from Greece, Personnel Review. 36 (2007) 227–294.

16. Kovach, K., Cathcart, C.: Human Resource Information Systems (HRIS), Providing

Business with Rapid Data Access, Information Exchange and Strategic Advantage. Public

Personnel Management. 28 (1999) 275–282

17. Wilcox, J.: The Evolution of Human Resources Technology, Management Accounting.

(1997) 3–5

18. Lawler, E., Mohrman, S.: HR as a Strategic Partner: What Does it Take too Make it Happen.

Human Resource Planning. 26 (2003) 15–29

19. Martin-Alcazar, F., Romero-Fernandez, P., Sanchez-Gardev, G.: Strategic Human Resource

Management: Intergrating the Universalistic, Contingent, Configurational and Contextual

Perspectives. International Journal of Human Resources Management. 16 (2005) 633–659.

20.

Schuler, R., Jackson, S.: Linking Competitive Strategies and Human Resource Management

Practices, Academy of Management Executive. 1 (1987) 13–29

21. Porter, M.: Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance, Free

Press , New York (1985)

22. Hannon, J., Jelf, G., Brandes, D.: Human Resource Information Systems: Operational

Issues and Strategic Considerations in a Global Environment. International Journal of

Human Resource Management. 7 (1996) 245–269

23. Ruel, H., Bondarouk, T., Van Der Velde, M.: The Contribution of E-HRM to HRM

Effectiveness, Employee Relations. 29 (2007) 280–291

24. Raudenbush, S., Bryk A.: Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis

Methods, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA (2002).

50