A COMPARISON OF WEB SITE ADOPTION IN SMALL AND

LARGE PORTUGUESE FIRMS

Tiago Oliveira and Maria F. O. Martins

Instituto Superior de Estatística e Gestão Informação, Universidade Nova de Lisboa

Campus de Campolide, 1070-312 Lisboa, Portugal

Keywords: Web site, adoption, small firms, large firms, information technology.

Abstract: This study compares the impact of different Technology-Organization-Environment (TOE) factors on the

web site adoption decision in small and large firms. A survey that was undertaken by the National Institute

of Statistics on the use of Information Technologies (IT) by firms in Portugal was used as the empirical

basis for this study. We found significantly differences in the factors that determined web site adoption

decision in small and large firms. While large firms are mainly influenced by organizational and

environmental factors, small firms are also concerned about the technological context. Moreover, the results

of our study suggested that, for Portuguese firms, the only factor that is equally important as web site

facilitator is competitive pressure.

1 INTRODUCTION

New IT, such as Internet enables firms to do

businesses in a different way (Porter, 2001). In order

to strength the potential of the Internet, firms are

establishing their presence on the Web: in 2005, the

overall percentage of enterprises in the EU with a

web site is 61%, but notably higher for larger firms

(90%) than for small firms (56%). Significantly

differences also exist between Member States: while

the leader countries, Sweden and Denmark, are

already reaching the saturation level for large firms

(97%), countries like Portugal (75%) and Latvia

(65%) are far away from this adoption level. For

small firms, this difference is greater: the web site

adoption level is 80% for Sweden compared with the

33% level for Portugal (Eurostat, 2006). Do

Portuguese small firm managers realize the strategic

value of owning a web-site in the same manner as

large firm managers? Or have they encountered

specific barriers to its implementation? Some studies

have been done to understand the differences in IT

adoption among European Countries (Zhu et al.,

2003) and much research attempted to comprehend

the relationship between firms size and IT adoption

decision (Lee and Xia, 2006). Some authors

(Grandon and Pearson, 2004, Premkumar, 2003)

suggested that the research findings on large

businesses cannot be generalized to small and

medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) because of the

unique characteristics of SMEs as for example the

lack of business and IT strategy, limited access to

capital resources and poor information skills. While

there exist an interesting and growing literature

addressing the determinants of IT adoption in the

specific context of SMEs (Harindranath et al., 2008,

Parker and Castleman, 2007,) and a limited research

for microfirms (Clayton, 2000), only a reduced

number of studies (Daniel and Grimshaw, 2002)

attempt to compare directly the approaches of small

and large firms to this new domain. Our work seeks

to fill this gap in the literature, by analysing the

relative importance of the factors that enable or

inhibit web site adoption by small firms compared

with large firms. The two main purposes of this

study are the following:

To examine the importance of technology-

organisational-environmental (TOE) related

factors as fundamental determinants of web

site adoption;

To analyze if the relative importance of such

factors is different for small and large firms.

To achieve these research objectives we used a rich

data set of 637 large firms and 3155 small firms that

are representative of Portuguese economy. The

understanding of the determinants of web site

adoption, at firm level, may be a useful tool in

370

Oliveira T. and F. O. Martins M. (2008).

A COMPARISON OF WEB SITE ADOPTION IN SMALL AND LARGE PORTUGUESE FIRMS.

In Proceedings of the International Conference on e-Business, pages 370-377

DOI: 10.5220/0001907603700377

Copyright

c

SciTePress

addressing the right type of policy measures to

stimulate the use of internet business solutions, with

the aim of enhancing the competitiveness and

productivity of Portuguese firms (Bertschek et al.,

2006, Black and Lynch, 2001, Bresnahan et al.,

2002, Brynjolfsson and Hitt, 2000, Dedrick et al.,

2003, Konings and Roodhooft, 2002, Martins and

Raposo, 2005, Zhu and Kraemer, 2002). This is

particularly needed in the case of Portugal which, for

several reasons, has been suffering from a serious

lack of competitiveness in comparison to other

industrialized economies. Our work has two

important contributions: the first is related to the

very limited research on comparing the determinants

of IT adoption in small and large firms. Secondly,

we present useful results for Portugal where there

are few published studies on the subject (Parker and

Castleman, 2007). The next section presents the

theoretical framework based on TOE approach.

Then, the proposed hypotheses are tested using an

econometric model. Finally, we present major

findings and conclusions.

2 THEORICAL FRAMEWORK

AND CONCEPTUAL MODEL

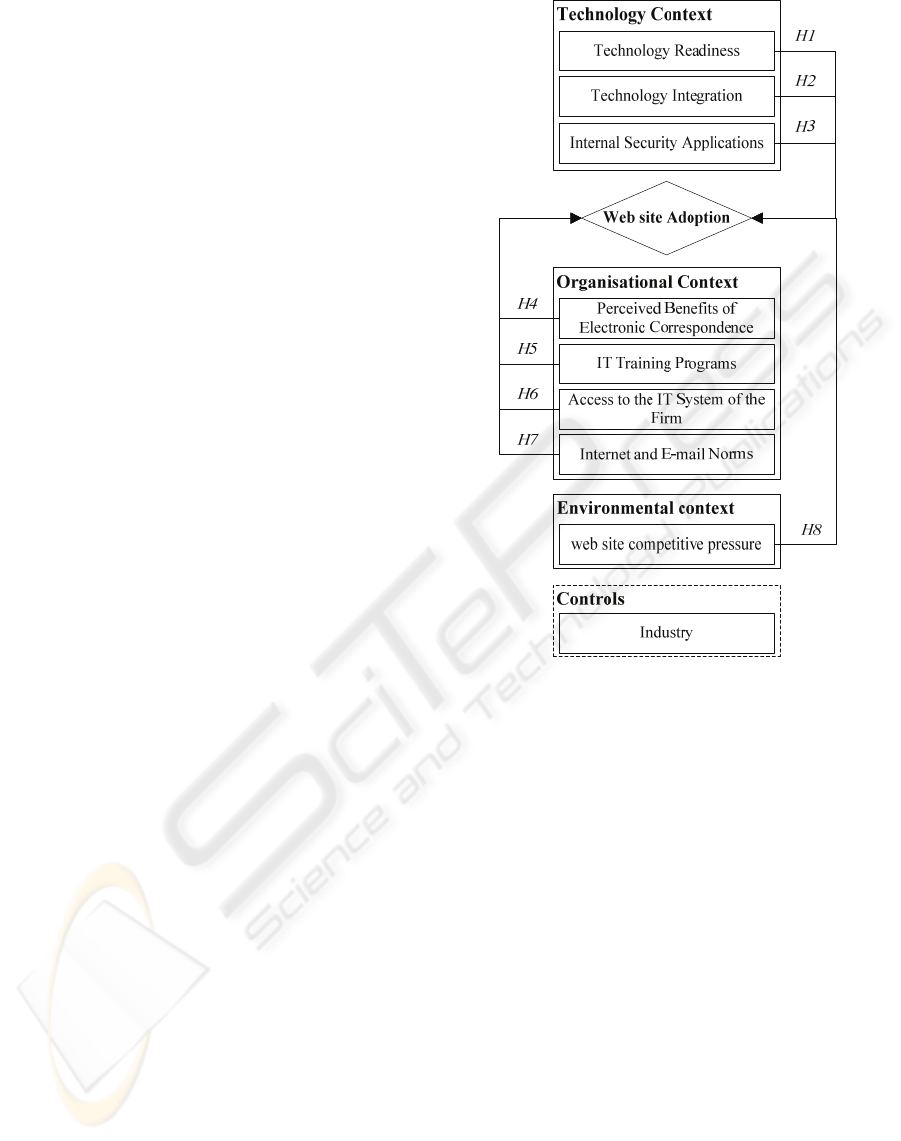

In this study we used the TOE framework,

developed by Tornatzky and Fleisher (1990) and

applied in many empirical studies related to IT

innovations. The TOE model identifies three aspects

that influence the adoption and implementation of

technical innovations by firms: technological

characteristics including factors related to internal

and external technologies of firms; organizational

factors relating to firm size and scope,

characteristics of the managerial structure of the

firm, quality of human resources; and environmental

factors that incorporate industry competitiveness

features. This theoretical background is the one used

by Iacovou et al. (1995), Kuan and Chau (2001) and

Premkumar and Ramamurthy (1995) to explain

electronic data Interchange (EDI) adoption and by

Thong (1999) to explain information system (IS)

adoption and Hong and Zhu (2006) to explain e-

commerce adoption. Empirical findings from these

studies confirmed that TOE methodology is a

valuable framework to understand the IT adoption

decision. In accordance with TOE theory, we

developed in the next subsection a conceptual

framework for web site adoption (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Conceptual framework for web site adoption.

2.1 Technology Context

Technology readiness can be defined as technology

infrastructure and IT human resources. Technology

readiness “is reflected not only by physical assets,

but also by human resources that are complementary

to physical assets” (Mata et al., 1995). Technology

infrastructure establishes a platform on which

internet technologies can be built; IT human

resources provide the knowledge and skills to

develop web applications (Zhu and Kraemer, 2005).

Theoretical assertions on the impact of Technology

readiness on IT adoption are supported by several

empirical studies, based on data sets representative

of all sizes of firms (Hong and Zhu, 2006, Zhu et al.,

2003, Zhu et al., 2006). These results where also

confirmed within the specific context of SMEs (Al-

Qirim, 2007, Dholakia and Kshetri, 2004, Kuan and

Chau, 2001, Mehrtens et al., 2001). Therefore, in

general we expected that firms with greater

technology readiness are in a better position to adopt

web sites. However, as suggested by others authors

(Daniel and Grimshaw, 2002, Parker and Castleman,

A COMPARISON OF WEB SITE ADOPTION IN SMALL AND LARGE PORTUGUESE FIRMS

371

2007, Premkumar, 2003), this factor will probably

affect in a different way small and large firms.

H1: The level of technology readiness is positively

associated with web site adoption but the impact will

vary between large and small firms

Before the internet, firms had been using

technologies to support business activities along

their value chain, but many were ‘‘islands of

automation’’— they lacked integration across

applications (Hong and Zhu, 2006). The

characteristics of the internet may help eradicate the

incompatibilities and rigidities of legacy information

systems (IS) and accomplish technology integration

among various applications and databases. Evidence

from the literature suggests that integrated

technologies may enhance firm performance by

reducing cycle time, improving customer service,

and lowering procurement costs (Barua et al., 2004).

We define technology integration as the systems for

managing orders that are automatically linked with

other IT systems of the firm. This type of factor

where also identified by Al-Qirim (2007) for the

specific case of SMEs. Therefore, we expect firms

with a higher level of technology integration to be

those who adopt web sites sooner. However,

probably there will be significantly differences

between small and large firms (Daniel and

Grimshaw, 2002). These reflections lead to the

following hypothesis:

H2: The level of technology integration is positively

associated with web site adoption, but the impact

will vary between small and large firms.

The lack of security may slow down technological

progress. For example, for Portugal in 2002 this was

the greatest barrier to internet use (Martins and

Oliveira, 2005) and in China it is one of the most

important barriers to the adoption of e-commerce

(Tan and Ouyang, 2004). We expect firms with a

higher level of internal security applications to be

more probable web site adopters. Within this

context, there is no empirical evidence suggesting a

same behaviour between small and large firms.

Therefore we stipulate the following:

H3: Internal security applications are positively

associated with web site adoption, but the impact

will probably vary between small and large firms.

2.2 Organization Context

Empirical studies consistently found that perceived

benefits have a significant impact in IT adoption.

This result is validated for medium to large firms

(Beatty et al., 2001), for SMEs (Iacovou et al., 1995,

Kuan and Chau, 2001) and for all size firms (Gibbs

and Kraemer, 2004). However, as suggested by

Daniel and Grimshaw (2002) small firms and large

firms perceived these benefits in a different. We

examine perceived benefits of electronic

correspondence and we postulate that:

H4: Perceived benefits of electronic correspondence

is positively related with web adoption, but the

impact will vary between small and large firms.

The presence of skilled labour in a firm increases its

ability to absorb and make use of an IT innovation,

and therefore is an important determinant of IT

diffusion (Caselli and Coleman, 2001, Hollenstein,

2004, Kiiski and Pohjola, 2002). Since the

successful implementation of new IT usually

requires complex skills, we expect firms with more

IT training programs to be more likely to adopt web

site. However, there will probably be differences

between firms due to the limited IT budgets of small

firms. We postulate the following:

H5: IT training programs are positively associated

with web site adoption, but the impact will vary

between small and large firms.

The fact that workers can have access to the IT

system from outside of the firm reveals that the

organisation is prepared to integrate its technologies.

However, this factor is expected to influence in a

different way small firms, where the number of

employees is small and their presence at the place of

work is more important than for large firms. We

postulate that:

H6: The level of access to the IT system from outside

of the firm is positively associated with web site

adoption, but the impact will vary between small and

large firms.

Regulatory environment has been acknowledged as

a critical factor influencing innovation diffusion

(Zhu et al., 2003, Zhu et al., 2004, Zhu et al., 2006).

Firms often refer inadequate legal protection for

online business activities, unclear business laws, and

security and privacy as concerns in using web

technologies (Kraemer et al., 2006). We postulate

that for small firms, this concern will probably be

different from their large counterparts.

H7: The presence of internet and e-mail norms is

positively associated with web site adoption, but the

impact will vary between small and large firms.

ICE-B 2008 - International Conference on e-Business

372

2.3 Environmental Context

Empirical evidence suggests that competitive

pressure is a powerful driver of IT adoption and

diffusion (Gibbs and Kraemer, 2004, Hollenstein,

2004, Zhu et al., 2004) and this fact is also verified

in small business research (Al-Qirim, 2007,

Dholakia and Kshetri, 2004, Grandon and Pearson,

2004, Iacovou et al., 1995, Kuan and Chau, 2001).

Therefore, we expect the probability of adopting a

web site to be positively influenced by the

proportion of web site adopters in the industry or

sector to which the specific firm is affiliated.

However, some studies suggested that competitive

pressure will be more significant in causing small

firms to adopt an IT than for larger firms, since they

need to protect their competitive position (Daniel

and Grimshaw, 2002). Therefore, we assume that:

H8: The level of web site competitive pressure is

positively associated with web site, but the impact

will vary between small and large firms.

2.4 Controls

We control, as usual, for industry or economic sector

effects. We used a dummy variable to control for

data variation that would not be captured by the

explanatory variables mentioned before.

3 DATA AND METHODOLOGY

3.1 Data

The data used in this study were provided by

National Institute of Statistics (INE) and result from

the survey On the use of Communication and

Information Technologies in Firms (Iutice) in 2006.

In our study we defined that small firms have less

than 50 employees and large firms have more than

250 employees. Our sample consists on 3155 small

and 637 large firms and is representative of the

Portuguese private sector excluding the financial one

3.2 Methodology

We estimated the following Probit Model:

P(y=1/x)=Ф(xβ) (1)

Where y=1 if firm decided to adopt a web site, and

zero otherwise, x is the vector of explanatory

variables, β the vector of unknown parameters to be

estimated, and Φ(.) is the standard normal

cumulative distribution. To analyse and compare the

influence of each factor on the probability of being a

web site adopter, we need to compute the marginal

effect of x

j

. This effect is obtained, for the

continuous variables, using the formula given by:

(

)

()

1/

j

j

Py

x

φ

β

∂=

=

∂

x

xβ

(2)

For the binary explanatory variables it is given by:

(

)

()()

1/

|, 1 |, 0

jj

j

Py

xx

x

Δ=

=

Φ=−Φ=

Δ

x

xβ xxβ x

(3)

where φ(.) is the density standard normal

distribution.

The vector of explanatory variables (x) includes:

A technology readiness (TR)

index that was built by

aggregating 8 items on technologies used by the firm

(on a yes/no scale): computers, e-mail, intranet,

extranet, own networks that are not the internet (own

exclusive networks), wired local area network

(Lange et al.), wireless LAN, wide area network

(WAN), and one item standing for existence of IT

specific skills in the firm (on a yes/no scale) (Zhu et

al., 2004). The first 8 items represent the penetration

of traditional information technologies, which

formed the technological infrastructure (Kwon and

Zmud, 1987). The last item represents IT human

resources (Mata et al., 1995). To aggregate the items

we used multiple correspondence analyses (MCA).

The MCA is a method of “multidimensional

exploratory statistic” that is used to reduce the

dimension when the variables are binary. For more

details see (Johnson and Wichern, 1998). The first

dimension explains 50% of inertia. In the negative

side of the first axis we have variables that represent

firms that do not use IT infrastructures and do not

have workers with IT skills. On the positive side we

have the variables that represent the use of

infrastructures and workers with IT skills.

Cronbach’s α, the most widely used measure for

assessing reliability (Chau, 1999), is equal to 0.8761,

indicating adequate reliability. Reliability measures

the degree to which items are free from random

error, and therefore yield consistent results.

Technology integration (TI)

was measured by the

number of IT systems for managing orders that are

automatically linked with other IT systems of the

firm (see appendix). The variable ranges from 0 to 5.

This variable reflects how well the IT systems are

connected on a common platform.

Internal security applications (ISA)

was measured

by the numbers of the use of internal security

A COMPARISON OF WEB SITE ADOPTION IN SMALL AND LARGE PORTUGUESE FIRMS

373

applications in the firms (see appendix). The

variable range from 0 to 6.

Perceived benefits of electronic correspondence

(PBEC) was measured by the shift from traditional

postal mail to electronic correspondence as the main

standard for business communication, in the last 5

years (on a yes/no scale).

IT training programs (ITTP)

is also a binary variable

(yes/no) related to the existence of professional

training in computer/informatics, available to

workers in the firm.

Access to the IT system of the firm (AITSF)

was

measured by the number of places from which

workers access the firms information system (see

appendix). The variable ranges from 0 to 4.

Internet and e-mail norms

(IEN) was measured by

whether firms have defined norms about internet and

e-mail (on a yes/no scale).

Web site competitive pressure (WEBP)

is computed

as the percentage of firms in each of the 9 industries

that had already adopted a web site two years before

the time of the survey, i.e. in 2004. As in Zhu et al.

(2003) the rationality underlying our model is that

an observation of the firm on the adoption behaviour

of its competitors influences its own adoption

decision.

Services (SER)

is a binary variable (yes/no) equal

one if firm belong to the service sector.

4 ESTIMATION RESULTS

The web site adoption model is estimated using

maximum likelihood. The estimation results for

small and large firms are presented in Table 1.

Goodness-of-fit is assessed in three ways. First, we

used log likelihood test, which reveals that our

models are globally statistic significant. Secondly

the discrimination power of the model is evaluated

using the area under the receiver operating

characteristic (ROC) curve, which is equal to 90.9%

and 78% for small and large firms, respectively.

Finally, the R

2

shows that the percentage explained

by the model is 41.9% for small firms and 15.7% for

large firms. The three statistical procedures reveal a

substantive model fit, a satisfactory discriminating

power and there is evidence to accept an overall

significance of the model.

Hypotheses H1-H9 were tested analysing the sign,

the magnitude, the statistical significance of the

coefficients and the marginal effects. As can be seen

from Table 1, for small firms, the estimation results

suggested that all the coefficients have the expected

signs and the only independent variable that is not

statistically significant is the access to the IT system

of the firm (AITSF). We can identify seven relevant

drivers of web site adoption for small firms:

technology readiness (TR), technology integration

(TI) and internal security application (ISA)

reflecting the technological context; perceived

benefits of electronic correspondence (PBEC), IT

training programs (ITTP) and internet and e-mail

norms (IEN), representing the organization context;

web site competitive pressure (WEBP), concerning

the environmental context. For large firms, we

identify four significant factors influencing web site

adoption decision: technology readiness (TR), IT

training programs (ITTP), access to the IT system of

firms (AITSF) and web site competitive pressure

(WEBP). In both cases, as expected, the economic

sector is a relevant factor (SER).

Table 1: Estimated coefficients for web site adoption

model.

Small firms Large firms

Technological context

- TR 1.044*** 0.346*

- TI 0.069*** -0.028

- ISA 0.170*** 0.038

Organizational context

- PBEC 0.293*** -0.039

- ITTP 0.235*** 0.644***

- AITSF 0.044 0.278***

- IEN 0.379*** 0.165

Environmental context

- WEBP 0.011*** 0.017***

Controls

- SER 0.185*** 0.306**

Constant -1.742*** -1.041***

Sample size 3155 637

LL -1038.5 -223.3

R

2

0.419 0.157

AUC 0.909 0.779

Note: * p-value<0.10; ** p-value<0.05; *** p-value<0.01.

The estimated marginal effects for the determinants

of web site adoption model, for small and large

firms, are reported in Table 2.

Their comparison reveals that, as expected, most of

the marginal effects vary between small and large

firms. The exception is the web site competitive

pressure impact that is the same for small and large

firms. Therefore hypotheses H1-H7 are validated

and H8 is not confirmed.

There are three additional aspects to be noted here.

Firstly, the technological context is much more

relevant for small firms than for large firms.

Secondly, within organizational context, perceived

benefits and internet e-mail norms are more

important to determine web site adoption for small

ICE-B 2008 - International Conference on e-Business

374

firms than for their larger counterparts. Finally, the

access to the IT system of the firm is relevant only

for large firms. As a whole, our results are in

accordance with those reported in studies comparing

IT adoption in large and small firms (Daniel and

Grimshaw, 2002). However, the limited number of

research in this specific domain difficult the

generalization of the results.

Table 2: Estimated marginal effects for web site adoption

model.

Small firms Large firms

Technological context

- TR 0.252*** 0.064*

- TI 0.017*** -0.005

- ISA 0.041*** 0.007

Organizational context

- PBEC 0.079*** -0.007

- ITTP 0.061*** 0.144***

- AITSF 0.011 0.051***

- IEN 0.100*** 0.032

Environmental context

- WEBP 0.003*** 0.003***

Controls

- SER 0.044*** 0.056**

Note: * p-value<0.10; ** p-value<0.05; *** p-value<0.01.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Within the context of an increased use of Internet

Business Solutions, such as web sites, this study fills

a gap in the literature by comparing the relative

importance of the factors influencing the adoption of

web sites for small and large firms. The theoretical

framework incorporates most of the facilitators and

inhibitor factors identified in other studies. The

research model evaluates, for small and large firms,

the impact of three technological factors, four

organizational factors and one environmental factor

on the web site adoption decision. Using a

representative sample of Portuguese small and large

firms, the estimation results for this comparative

study reveal that the important determinants of web

site adoption decision vary with size of a firm. Other

studies in this domain (Daniel and Grimshaw, 2002,

Premkumar, 2003) also suggested that the problems,

opportunities, and management issues encountered

by small business in the IT area are different from

those faced by their larger counterparts. However,

our study provides a more in depth analysis since it

identifies those factors that more or less relevant for

large/small firms and quantifies its impact on web

site adoption decision. These findings have practical

implications for managers and policy makers.

Firstly, policy makers should be conscious that the

motivations towards the IT adoption are different for

small and large firms. Therefore, government

initiatives, such as the Technological Plan, for

Portugal, must be different for small and large firms,

namely those related to procurement incentives.

Secondly, managers should be aware that technology

readiness constitutes both physical infrastructure and

intangible knowledge such as IT skills. This urges

top leaders (mainly in small firms) to foster

managerial skills and human resources that possess

knowledge of these new information technologies.

Therefore, there is a business opportunity for IT

firms to establish the service that support the small

size firms in the technological context. In our

opinion this is particularly important in Portugal

given the relative importance of small businesses in

the economy (Vicente and Martins, 2008). Finally,

our study sought to help firms become more

effective in moving from a traditional channel to the

internet by identifying the profile of early web site

adopters.

As in most empirical studies, our work is limited in

several ways. The cross-sectional nature of this

study does not allow knowing how this relationship

will change over time. To solve this limitation the

future research should involve panel data. Another

limitation of our work is that it only investigates web

site adoption decision. To provide a more balanced

view of firms’ IT adoption decision, other Internet

Business Solutions, such as e-commerce should also

be examined.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the National Institute

of Statistics (INE) for providing us with the data.

REFERENCES

Al-Qirim, N. (2007) The adoption of eCommerce

communications and applications technologies in

small businesses in New Zealand. Electron. Commer.

Rec. Appl., 6, 462-473.

Barua, A., Konana, P., Whinston, A. B. & Yin, F. (2004)

Assessing internet enabled business value: An

exploratory investigation. MIS Quart, 28, 585-620.

Beatty, R. C., Shim, J. P. & Jones, M. C. (2001) Factors

influencing corporate web site adoption: a time-based

assessment. Information & Management, 38, 337-354.

Bertschek, I., Fryges, H. & Kaiser, U. (2006) B2B or Not

to Be: Does E-commerce Increase Labor Productivity?

International Journal of the Economics of Business,

13, 387-405.

A COMPARISON OF WEB SITE ADOPTION IN SMALL AND LARGE PORTUGUESE FIRMS

375

Black, S. E. & Lynch, L. M. (2001) How to compete: The

impact of workplace practices and information

technology on productivity. Review of Economics and

Statistics, 83, 434-445.

Bresnahan, T. F., Brynjolfsson, E. & Hitt, L. M. (2002)

Information technology, workplace organization, and

the demand for skilled labor: Firm-level evidence.

Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117, 339-376.

Brynjolfsson, E. & Hitt, L. M. (2000) Beyond

Computation: Information Technology, Organizational

Transformation and Business Performance. Journal of

Economic Perspectives, 14, 23-48.

Caselli, F. & Coleman, W. J. (2001) Cross-country

technology diffusion: The case of computers.

American Economic Review, 91, 328-335.

Chau, P. (1999) On the use of construct reliability in MIS

research: a meta-analysis. Information &

Management. 35(4), 217-227.

Clayton, K. (2000) Microscope on micro businesses.

Australian CPA, 2, 46–7.

Daniel, E. M. & Grimshaw, D. J. (2002) An exploratory

comparison of electronic commerce adoption in large

and small enterprises. Journal of Information

Technology, 17, 133-147.

Dedrick, J., Gurbaxani, V. & Kraemer, K. L. (2003)

Information technology and economic performance: A

critical review of the empirical evidence. Acm

Computing Surveys, 35, 1-28.

Dholakia, R. R. & Kshetri, N. (2004) Factors Impacting

the Adoption of the Internet among SMEs. Small

Business Economics, 23, 311-322.

Eurostat (2006) The internet and other computer networks

and their use by European enterprises to do eBusiness.

Statistics in focus.

Gibbs, L. J. & Kraemer, K. L. (2004) A Cross-Country

Investigation of the Determinants of Scope of E-

commerce Use: An Institutional Approach. Electronic

Markets, 14, 124-137.

Grandon, E. E. & Pearson, J. M. (2004) Electronic

commerce adoption: an empirical study of small and

medium US businesses. Information & Management,

42, 197-216.

Harindranath, G., Dyerson, R. & BARNES, D. (2008), ICT

Adoption and Use in UK SMEs: a Failure of

Initiatives?, Electronic Journal of Information Systems

Evaluation, 11(2), 91-96.

Hollenstein, H. (2004) Determinants of the adoption of

Information and Communication Technologies (ICT).

An empirical analysis based on firm-level data for the

Swiss business sector. Structural Change and

Economic Dynamics, 15, 315-342.

Hong, W. Y. & Zhu, K. (2006) Migrating to internet-based

e-commerce: Factors affecting e-commerce adoption

and migration at the firm level. Information &

Management, 43, 204-221.

Iacovou, C. L., Benbasat, I. & Dexter, A. S. (1995)

Electronic data interchange and small organizations:

Adoption and impact of technology. Mis Quarterly,

19, 465-485.

Johnson, R. & Wichern, D. (1998) Applied Multivariate

Data Statistical Analysis, New Jersey, Prentice Hall.

Kiiski, S. & Pohjola, M. (2002) Cross-country diffusion of

the Internet. Information Economics and Policy, 14,

297-310.

Konings, J. & Roodhooft, F. (2002) The effect of e-

business on corporate performance: Firm level

evidence for Belgium. Economist-Netherlands, 150,

569-581.

Kraemer, K. L., Dedrick, J., Melville, N. & Zhu, K. (2006)

Global E-Commerce: Impacts of National

Environments and Policy, Cambridge, UK.

Kuan, K. K. Y. & Chau, P. Y. K. (2001) A perception-

based model for EDI adoption in small businesses

using a technology-organization-environment

framework. Information & Management, 38, 507-521.

Kwon, T. H. & Zmud, R. W. (1987) Unifying the

fragmented models of information systems

implementation. In critical issues in Information

Systems Research (Boland RJ and Hirschheim RA,

Eds). IN WILEY, J. (Ed.) New York.

Lange, T., Ottens, M. & Taylor, A. (2000) SMEs and

Barriers to Skills Development: a Scottish Perspective.

Journal of Industrial Training, 24, 5-11.

Lee, G. & Xia, W. D. (2006) Organizational size and IT

innovation adoption: A meta-analysis. Information &

Management, 43, 975-985.

Martins, M. R. F. & Raposo, P. (2005) Measuring the

Productivity of Computers: A Firm Level Analysis for

Portugal. Electronic Journal of Information Systems

Evaluation, 8, 197-204.

Martins, M. R. F. & Oliveira, T. (2005) Characterisation

of Portuguese Organizations regarding Investment in

Information and Communication Technologies –

Application of Multivariate Data Analysis Techniques.

IN REMENYI, D. (Ed.) The 12th European

Conference on Information Technology Evaluation.

Turku, Finland, Academic Conferences Limited.

Mata, F., Fuerst, W. & Barney, J. (1995) Information

technology and sustained competitive advantage: A

resource-based analysis. MIS Quart, 19, 487–505.

Mehrtens, J., Cragg, P. B. & Mills, A. M. (2001) A model

of Internet adoption by SMEs. INFORMATION &

MANAGEMENT, 39, 165-176.

Parker, C. M. & Castleman, T. (2007) New directions for

research on SME-eBusiness: insights from an analysis

of journal articles from 2003 to 2006. Journal of

Information Systems and Small Business, 1, 21-40.

Porter, M. E. (2001) Strategy and the Internet. Harvard

Business Review, 79, 62-78.

Premkumar, G. (2003) A meta-analysis of research on

information technology implementation in small

business. Journal of Organizational Computing and

Electronic Commerce, 13, 91-121.

Premkumar, G. & Ramamurthy, K. (1995) The role of

interorganizational and organizational factors on the

decision mode for adoption of interorganizational

systems. Decision Sciences, 26, 303-336.

ICE-B 2008 - International Conference on e-Business

376

Tan, Z. & Ouyang, W. (2004) Diffusion and Impacts of

the Internet and E-commerce in China. Electronic

Markets, 14, 25-35.

Thong, J. Y. L. (1999) An Integrated Model of

Information Systems Adoption in Small Businesses.

Journal of Management Information Systems 15, 187-

214.

Tornatsky, L. & Fleischer, M. (1990) The Process of

Technology Innovation, Lexington, MA, Lexington

Books.

Vicente, M. R. C. & Martins, M. O. (2008) Information

Technology, efficiency and productivity in SMEs:

Evidence for Portugal. paper presented at the Telecom

Paris Tech Conference on The Economics of ICT.

Paris.

Zhu, K., Kraemer, K. & XU, S. (2003) Electronic business

adoption by European firms: a cross-country

assessment of the facilitators and inhibitors. European

Journal of Information Systems, 12, 251-268.

Zhu, K., Kraemer, K. K. L., XU, S. & DEDRICK, J.

(2004a) Information technology payoff in e-business

environments: An international perspective on value

creation of e-business in the financial services

industry. Journal of Management Information

Systems, 21, 17–54.

Zhu, K. & Kraemer, K. L. (2002) e-Commerce metrics for

net-enhanced organizations: Assessing the value of e-

commerce to firm performance in the manufacturing

sector. Information Systems Research, 13, 275-295.

Zhu, K. & Kraemer, K. L. (2005) Post-adoption variations

in usage and value of e-business by organizations:

Cross-country evidence from the retail industry.

Information Systems Research, 16, 61-84.

Zhu, K., Kraemer, K. L. & XU, S. (2006) The Process of

Innovation Assimilation Assimilation by Firms in

Different Countries: A Technology Diffusion

Perspective on E-Business. MANAGEMENT

SCIENCE, 52, 1557-1576.

APPENDIX

Technological integration

Did your firm's IT systems for managing orders link

automatically with any of the following IT systems

during January 2006? (Yes No)

a) Internal system for re-ordering replacement

supplies

b) Invoicing and payment systems

c) Your system for managing production, logistics or

service operations

d) Your suppliers’ business systems (for suppliers

outside your firm group)

e) Your customers’ business systems (for customers

outside your firm group)

Internal security applications

Did your firm use the following internal security

applications, during January 2006? (Yes No)

a) Virus checking or protection software

b) Firewalls (software or hardware)

c) Secure servers (support secured protocols such as

http)

d) Off-site data backup

e) Subscription of a security service (e.g. antivirus or

network intrusion alert)

f) Anti-spam filters (unsolicited e-mails)

Access to the IT system of the firm

Did any of those people access the firm's computer

system from the following places during January

2006? (Yes No)

a) From home

b) From customers or other external business

partners’ premises

c) From other geographically dispersed locations of

the same firm or firm group

d) During business travels, e.g. from the hotel,

airport etc.

A COMPARISON OF WEB SITE ADOPTION IN SMALL AND LARGE PORTUGUESE FIRMS

377