A UNIFIED APPROACH FOR RECONCILING CHARACTERS

AND STORY IN THE REALM OF AGENCY

Rossana Damiano and Vincenzo Lombardo

Dipartimento di Informatica e CIRMA, Universit

`

a degli Studi di Torino

C.so Svizzera 185, Torino, Italy

Keywords:

Interactive Drama, Artificial Characters, Intelligent Agents.

Abstract:

In the last decade, a number of computational systems for entertainment and communication have appeared,

that share a set of common features, including the use of artificial characters and the reference to drama

and storytelling. Systems for interactive storytelling and drama rely on agent theories to model characters,

and adopt planning techniques to cope with non-determinism at the story level, combining them according to

sophisticate architectural designs. However, a consolidated approach has not emerged yet, that fully reconciles

these two dimensions. In this paper, we propose a unifying framework to accommodate the tension between

story control and character behavior and we claim that the accurate modeling of agency is a prerequisite to the

success of attempts to solve this tension. By using this framework to analyze practical systems we point out

that the importance of agency is acknowledged by successful systems, although only implicitly in most cases.

1 INTRODUCTION

In the last decade, a number of systems for enter-

tainment and communication have appeared that –

notwithstanding different design goals and concep-

tions – share a number of common features, includ-

ing the use of artificial characters and the adoption of

storytelling to structure the interaction with the user.

These systems rely on multiple modalities for com-

municating with the user, such as natural language,

graphics or virtual reality, and support different styles

of interaction, such as dialogue, direct manipulation

or embodiment.

For example, the Fac¸ade entertainment system in-

volves the user as an active character in a dramatic

situation in which a couple whose marriage is falling

apart invites her/him for a drink, with wife and hus-

band trying to bring the user on their respective sides.

In the interactive storytelling system by (Pizzi et al.,

2007), the user is immersed in a virtual reality envi-

ronment, where he/she plays the part of one of the

characters of the French novel “Madame Bovary”, in-

teracting with the other characters and affecting their

feelings and behavior. In the Dramatour guide appli-

cation for cultural heritage (Damiano et al., 2006), a

virtual character, the spider Carletto, accompanies the

visitor in a historical location from a portable device,

exhibiting an inner conflict between ‘guide’ and ‘sto-

ryteller’. In the FearNot! edutainment system (Aylett

et al., 2007), the dynamics underlying bullying inci-

dents in schools is dramatized in a cartoon-like en-

vironment, in which the child user intervenes as an

empathic observer to give advice to the victim.

Given this heterogeneity of goals and instruments,

a first, broad distinction has been established in the lit-

erature between story-based and character-based sys-

tems (Mateas and Stern, 2003; Pizzi et al., 2007; The-

une et al., 2003; Riedl and Young, 2006). Story-

based systems are characterized by centralized archi-

tectures, in which the behavior displayed by the sys-

tem, possibly through characters’ mediation, is driven

by the unifying principle of a story. The story to be

conveyed is usually underspecified in some way, so as

to provide some limited support to non-determinism

and interactivity. Character-based systems rely on the

autonomous behaviour of characters to create situa-

tions, which are then interpreted as emergent narrative

structures (Spierling, 2007).

Whatever the chosen approach, it is widely ac-

knowledged that the author’s control over the story

430

Damiano R. and Lombardo V. (2009).

A UNIFIED APPROACH FOR RECONCILING CHARACTERS AND STORY IN THE REALM OF AGENCY.

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence, pages 430-437

DOI: 10.5220/0001662004300437

Copyright

c

SciTePress

is related with communicative effectiveness; how-

ever, it must be traded off against the autonomy and

the believability of the characters. For some specific

forms of communication and entertainment, clear de-

sign strategies have emerged: for example, in video

games, the quality of playability, anchored in care-

fully shaped and strongly constrained stories, is pre-

ferred over the definition of psychologically believ-

able, autonomous characters. On the contrary, AI sys-

tems generally envisage interactivity as a main ob-

jective, sustained by a rich literature on interactive

storytelling and drama (Murray, 1998; Ryan, 2006;

Wardrip-Fruin and Harrigan, 2004). However, a con-

solidated approach has not emerged yet that fully rec-

onciles the two conflicting dimensions of story and

characters.

In this paper, we sketch a formal system that sys-

tematizes the functions of story and characters in a

unified theoretical framework.

By using this framework, we accommodate the

components of a variety of practical systems, pointing

out the relevance of the notion of agency as a prereq-

uisite to reconciling story and characters.

2 A FORMAL FRAMEWORK

FOR DRAMA

The theoretical framework presented in this section

lays out the ‘language of drama’, independently of the

form and the media through which specific dramas are

realized. Based on previous work by (Damiano et al.,

2005), revised here with a particular concern towards

the contribution of AI and agents, the framework en-

compasses the main feature of the practical systems

mentioned above.

Given the drama literature (Egri, 1946; McKee,

1997), for ‘drama’ we intend a form of narrative that

describes the story via characters’ action in present

time and has a carefully crafted premise, i.e., an au-

thorial direction that shapes the dramatic climax until

its solution.

Given this definition, the drama framework con-

sists of two levels, the directional level, that encodes

the specific traits of drama, and the actional level, that

connects such traits with the notion of agency. The di-

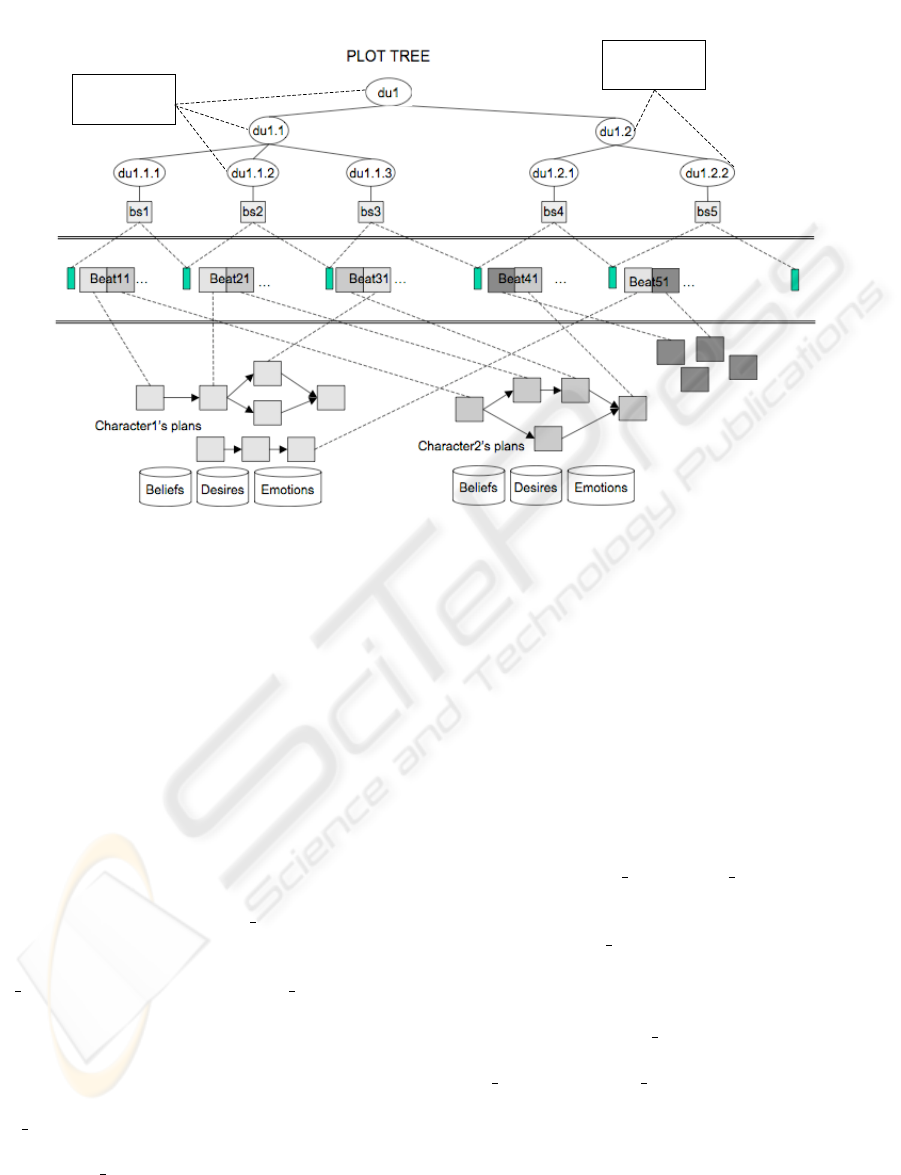

rectional level of the system (Fig. 1, top) is centered

on the notion of drama unit. A drama unit (du) is any

segment of the drama that contributes to the story ad-

vancement. Each advancement is due to a change of

polarity of some value at stake for one or more char-

acters (McKee, 1997); values refer to emotional states

or belief states.

Originally expressed by Aristotle as “unity of ac-

tion”, a drama unit provides an effective direction for

the story advancement operated by the segment of the

story to which it is associated.

Emotional states refer to a cognitive model of

emotions like the one stated by Ortony, Clore and

Collins (Ortony et al., 1988); this model, largely

employed in interactive drama (starting from (Bates

et al., 1994)), defines emotion types based on an

agent’s appraisal of self and other agents’ actions,

thus naturally lending itself to accommodate the di-

alectics of characters in drama. Belief states can be

any predicate logic formula.

A drama unit can be recursively expanded into a

number of children drama units, forming the plot tree

(Fig. 1, top left). The plot tree is licensed by the

formal rules of drama, which pose constraints on the

expansion relationship of dus (dominance relation in

formal grammar terms). In particular, the direction

of the parent du must include all the value at stake of

children dus, with consistent initial and final polarities

in case of subsequent changes.

The expansion of drama units into sub drama units

stops when, at the basic recursion, drama units are

expanded into a sequence of beats (bs in Fig. 1, bot-

tom). This sequence constitutes the actional level of

drama. Beats are the minimal units for the story ad-

vancement, that will be exposed to the audience.

Beats consist of incident pairs, where incidents are

characters’ actions – executed as part of their plans –

or unintentional events (represented by pairs of adja-

cent boxes in the central part of Fig. 1). While only

beliefs and emotions are represented at the directional

level,

at the actional level a model of agency, such as the

belief–desire–intention (BDI) model (Bratman et al.,

1988), provides the glue that links the behavior of

characters into a coherent causal chain and sustains

the believability of the characters.

The prescription that the direction is achieved

through conflict is captured by constraint that, for

each beat,

the intended outcome of the second incident

should be incompatible with the intended outcome of

the first incident, directly or indirectly.

In order to illustrate how this framework ap-

plies to specific drama, we resort to a well-known

example, the ‘nunnery scene’ from Shakespeare’s

Hamlet, describing how the characters’ rational and

emotional states are plotted by the author to achieve

the direction of the scene.

1

For all the segments

that compose the scene, we sketch the structure of

1

The scene has been analysed also by (Damiano and

Pizzo, 2008) in an actional perspective.

A UNIFIED APPROACH FOR RECONCILING CHARACTERS AND STORY IN THE REALM OF AGENCY

431

directional level

actional level

Character1’s

values

Character2’s

values

Figure 1: A graphical representation of the formal system of drama. On top, the directional level of drama, i.e. the way it

accomplishes its direction through a sequence of elements situated at different levels of abstraction (dus), which manipulate

characters’ values; below, the actional level, represents the anchoring of the direction into the characters’ actions contained in

beats and rooted in a rational and emotional model of agency.

the scene in terms of characters’ values (beliefs and

emotions), with the goal of showing how the plot

incidents affect these values (a formal derivation is

omitted for space reasons). Emotional values refer to

the ‘ontology of emotions’ described in (Ortony et al.,

1988); the modifications of values are represented by

their changes of polarity.

The scene has a tripartite structure; the value

at stake of the overall scene is Hamlet’s attitude

toward Ophelia (changing from positive to neg-

ative), h f eel(Hamlet, love f or(Ophelia)), +i.

In the first part, Ophelia is sent to Hamlet by

Claudius to induce him to reveal his inner feelings,

has goal(Ophelia, tell(Hamlet, inner f eelings)))),

as a way to confirm the hypothesis that his mad-

ness is caused by his rejected love for Ophelia.

In order to do so, she has formed a simple plan

that consists of starting an interaction with Hamlet,

and asking him to talk about his inner feelings

(has plan(Ophelia, (meet(Ophelia, Hamlet), start −

interaction(Ophelia, Hamlet), ask(Ophelia, tell(

Hamlet, inner f eelings)))). Hamlet, who does

not want to foolish Ophelia (for whom he still

has a strong affection), tries to leave her, but

is forced to answer by Ophelia’s insistence, as

she makes subsequent attempts to start an in-

teraction with him. This segment of the scene

establishes Polonius’ value at stake, a belief state

in which he knows that Hamlet is mad because of

rejected love hbel(Polonius, mad(Hamlet)), −i;

Ophelia’s value is an emotional state that

includes fear about Hamlet’s madness,

h f eel(Ophelia, f ear f or(Hamlet madness)), −i

and hope (related with the fulfillment of her task

to convince Hamlet to reveal his inner feelings,

tell(Hamlet, inner f eelings).

At the beginning of the second part,

Hamlet reactively forms the goal of sav-

ing Ophelia from the corruption of Elsi-

nore court, has goal(Hamlet, save(Hamlet,

Ophelia)), by inducing her to go to a nunnery

(has goal(Hamlet, has goal(Ophelia, go(Ophelia,

nunnery)))). In order to do so, he resorts to a rhetor-

ical plan to convince her that moral and affective

values do not hold anymore, and that everybody,

including himself, is corrupted, with the intention

that she would spontaneously decide to go to the nun-

nery (bel(Hamlet, (bel(Ophelia, corrupted(court))

ICAART 2009 - International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

432

→ has goal(Ophelia, go(Ophelia, nunnery))))).

Hamlet’s value at stake is now set to hope about

Ophelia’s decision (and her consequent salva-

tion), h f eel(Hamlet, hope(go(Ophelia, nunnery)

)), +i, while Ophelia’s value at stake is a be-

lief state about the corruption of the court,

hbel(Ophelia, corrupted(court)), −i.

Finally, in the third part of the scene, Ham-

let verifies whether he has convinced Ophelia

that the court is corrupted, i.e., if h(bel(Ophelia,

corrupted(court)), +i holds. Prompted by the

fact – a contingent event – that he has noticed

Claudius and Polonius hidden behind the curtains,

hbel(Hamlet, (overhearing(Claudius)), +i, he real-

izes that she maybe be lying and asks her where her

father is. For Hamlet, this is a way to verify if Ophe-

lia is still subdued to his father’s authority. As she

answers that her father is at home, her lie, for Hamlet,

counts as a confirmation that his plan has failed (since

the belief that the entire court is corrupted should re-

tain her from obeying her father): so, Hamlet is upset.

He starts feigning madness again, thus

confirming Claudius’ and Polonius’ beliefs

about him, hbel(Polonius, mad(Hamlet)), +i;

the scene ends with Ophelia complaining

about her tragic destiny. Hamlet’s value at

stake is his emotional attitude towards Ophe-

lia h f eel(Hamlet, love f or(Ophelia)), −i,

while his hope to convince Ophelia to go

to the nunnery turns into disappointment,

h f eel(Hamlet, hope (go(Ophelia, nunnery))), −i,

and anger, h f eel(Hamlet, anger(not(bel(Ophelia,

corrupted(court))), +i, At the same time,

Ophelia experiences the emotional state of

fear confirmed about Hamlet’s madness,

h f eel(Ophelia, f ear con f irmed(Hamlet madness)),

+i, not at all mitigated by the fact of having ac-

complished her initial task h f eel(Ophelia, sel f −

satis f action(done(tell(Hamlet, inner f eelings))),

+i.

The directional level corresponds to the authorial con-

trol over drama; at this level, the author puts the char-

acters’ values at stake, abstracting from the actions

represented in the plot, with the intent of establish-

ing the story meaning by manipulating the charac-

ters’ values. The outcome of an incident, be it action

or event, affects the characters’ values that are put at

stake at the directional level, so that the the story ad-

vances at the directional level as prescribed by the au-

thor. However, the outcomes of characters’ actions

not only affect their values, but must be coherent with

their goals; also, unintentional events must be plau-

sible as naturally occurring (like the revelation that

Polonius and Claudius are hidden behind the curtains

in this scene).

For instance, in the third part of the example scene,

Hamlet formulates the goal of knowing whether

Ophelia is lying or not, as a way to monitor the ac-

tual outcome of his rhetorical plan to convince Ophe-

lia that the court is corrupted and subtract her from

the submission to her father. By choosing to do it by

asking Ophelia about her father, he opportunistically

exploits the circumstance – of which he has just be-

come aware – that Claudius and Polonius have been

hiding behind the curtains to eavesdrop. Hamlet’plan

to know if Ophelia is sincere consists in asking her

directly, and when he comes to know that Ophelia is

lying, his value at stake of hope is consequently set

to a negative value. At the same time, since drama

units are part of a hierarchical structure, Ophelia’s an-

swer affects Hamlet’s value

at stake for the overall

scene, i.e., it turns Hamlet’s love to a negative value,

a change of major importance for the entire play.

As this short excerpt illustrates, at the ac-

tional level, even sophisticated characters like Shake-

speare’s show the typical behavior of rational agents:

they recognizably have goals, they form plans to

achieve them and monitor the execution of those

plans, a behavior that is apparent in the acts performed

by Ophelia and Hamlet. Moreover, they reactively

form new goals (e.g., Hamlet decides to act so as to

save Ophelia from the corruption of the court when

he realizes the necessity and the opportunity to do it)

and drop the goals that have proven unachievable (see

Hamlet’s utter disappointment when confronted with

his failure, and the similar feeling displayed by Ophe-

lia by the end of the scene). Rationality, then, is in-

tegrated with the emotional states that are determined

by the appraisal of the characters’ own goals and of

the other characters’ goals; emotional states in turn

affect the deliberative processes of the characters, by

providing the motivation for action, thus yielding the

complex interplay of emotions and rationality that can

be observed in drama.

3 APPLYING THE FORMAL

FRAMEWORK TO PRACTICAL

ARCHITECTURES

In the following, we use the framework sketched in

the previous section as a conceptual instrument to an-

alyze a sample of systems, that span a multiplicity of

relevant approaches and are characterized by the use

of a variety AI theories and techniques. With respect

to the dichotomy between story-based and character-

based approaches, the adoption of a unifying formal

A UNIFIED APPROACH FOR RECONCILING CHARACTERS AND STORY IN THE REALM OF AGENCY

433

framework brings the advantage of situating differ-

ent systems against a background in which the two

dimensions of story and characters are explicitly put

in relation, thus providing a common evaluation grid.

Moreover, the way each system copes with the tension

between story design and characters’ autonomy has

relevant consequences for the role of the procedural

author (Murray, 1998) who will input the knowledge

in the system.

3.1 Directional Level

In practical systems, setting the focus on the direc-

tional level corresponds to giving the author direct

control on the direction of the story and frustrating the

autonomy of characters. Since the directional level

manipulates facts that relate, more or less directly,

with the properties of characters (represented by the

‘values at stake’ in the drama framework), the inter-

nal structure of characters – a sum of emotions and

beliefs – must be represented in a more or less explicit

way.

Without a representation of this kind, it would not

be possible, for example, to set up intriguing situa-

tions in which the characters’ values are affected by

their intentional behavior, but in the opposite way

than planned by the characters themselves. For ex-

ample, Hamlet’s attempt to save Ophelia, motivated

by his love for her, is not only frustrated but ends up

turning into disappointment the feeling that initially

prompted him to act.

The intentional aspects of the characters’ behav-

ior, then, are dealt with in different way. A strategy

consists of infusing a representation of the intentions

of the character at the level of story control, so as to

constrain the evolution of the story to coherent char-

acter behavior; or, reversing the perspective, the au-

tonomy of characters in the system can be constrained

to sequences of actions that are known to be consis-

tent in advance, a typical property of pre-compiled

plans.

In general, story-based systems tend to operate

at the directional level and incorporate sophisticated

story models (object-level knowledge about the se-

mantics of drama according to the drama framework)

to account for the structural aspects of narration and

drama, ranging from semiotic structuralism (Szilas,

2003; Peinado and Gerv

´

as, 2004; Hartmann et al.,

2005) to cognitive models of story understanding

(Swartjes and Theune, 2006). The knowledge about

story generation has often been encoded in the form of

logical rules, like in DEFACTO (Sgouros, 1999) and

the IDtension (Szilas, 2003). These systems closely

resemble expert systems, mixing the empirical and

theoretical knowledge of the author in a set of rules

that the system uses to generate the story; the effec-

tiveness of these systems seems to be directly con-

nected to their ability to integrate actional operators

and emotional aspects.

Alternatively, a family of successful systems re-

sort to AI planning for the generation of the story. In

these systems, the planner may replace the author in

devising the plot: planning operators are represented

by a set of possible plot incidents (Riedl and Young,

2006), which can be combined in a consistent se-

quence to achieve a transition from a author-defined

initial and final state, with explicit constraints on the

ordering of incidents and their causal relations (where

intentionality can represent a weak form of causa-

tion). Or, the planner may be in charge of solving

a planning problem from the perspective of the story

characters, delegating the control over the direction to

the author’s capability of encoding full-fledged drama

units into joint planning operators (Mateas and Stern,

2005).

The control over the story direction is largely

preferred to the manipulation of characters when it

comes to designing authoring tools, as exemplified

by a recent generation of systems (Weiss et al., 2005;

Iurgel, 2006; Medler and Magerko, 2006). In partic-

ular, (Medler and Magerko, 2006) propose a hybrid,

layered language for drama representation in author-

ing tools, aimed at allowing the author to design the

story at the directional level, as a partially ordered

set of plot points, while leaving the story generation

system the task of mapping this representation onto a

planning formalism. Similarly, the Automated Story

Director (Riedl and Stern, 2006) confines the auton-

omy of characters to the generation of low-level be-

haviors based on action libraries, giving to a ‘drama

manager’ (Mateas and Stern, 2003) the responsibil-

ity for monitoring the story advancement to preserve,

during the interaction with the user, the story goals

encoded by the author.

Moreover, within each family of systems (rule-

based, planning-based and hybrid), several alterna-

tives are available concerning the techniques em-

ployed and the system architecture.

The Mimesis (Riedl and Young, 2006) storytelling

system, explicitly aims at constraining the interaction

with the user to the realization of a specific direc-

tion. The story is generated offline by a partial or-

der planner given the direction posed by the author;

the planner assembles actions executed by a set of

characters in order to construct an overall plan that

fulfills the goal stated by the author. The plan is an-

alyzed to detect the potential impact of user’s input,

and converted into a conditional plan in which this in-

ICAART 2009 - International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

434

put is accounted for in advance. This powerful tech-

nique, called ‘narrative mediation’, allows the author

to know, in full detail, the possible forms of the plot.

At the same time, the system sees to it that the in-

tentions of the characters remain clearly recognizable

to the user along the plan, and that no actions are in-

serted into the plan only to meet the needs of drama,

without being part of the motivational structure of the

characters. The core of this system clearly operates

at the directional level; however,the representation of

the characters as agents is acknowledged, though indi-

rectly, by the use of “intention frames”, motivational

accounts with which the actions included in the plot

are annotated. A drawback of this strategy is that the

mental state of the characters are accounted for only

indirectly, blurring the conceptual distinction between

the goals that are individually pursued by the charac-

ters and the drama goal.

The Fac¸ade system (Mateas and Stern, 2005) is

designed to conduct an interactive drama to a clearly

stated set of outcomes, in which the couple of protag-

onists either split or remain together (see Section 1),

with the user being neutral or sympathizing for one

of the two sides. In Fac¸ade, the richness of the user

experience resides in the user becoming a protagonist

of the story, triggering (but not controlling) the evo-

lution of the plot towards one of the available direc-

tions. The generation of the plot is obtained through a

hierarchical plan language (ABL), that encodes multi-

agent, joint plans; the plan language also accounts for

the role of the user in the joint action. Using ABL, the

author defines a set of beats, which represent interper-

sonal conflicts among the characters. The inclusion of

the joint plans in the interactive story is then affected

by the interaction with the user and guided by a mea-

sure of the plot emotional value.

This system lends itself to represent stereotypical

situations of western drama, in which the perspec-

tive on characters is somewhat reversed with respect

to the rational and emotional approach to agency un-

derpinning the formalization we propose: in Fac¸ade,

the characters tend to be shaped by the actions they

perform and the things they say in the space of the

interpersonal relations, instead of being stated by an

a priori definition of their mental state from which

intentions can subsequently be derived, according to

the standard practice that characterizes agent architec-

tures (Rao and Georgeff, 1991; Wooldridge and Par-

sons, 1999). For this reason, even if this system op-

erates at the directional level, it is situated mid-way

between the directional level and the actional level.

3.2 Actional Level

In general, character-based systems are situated at

the actional level of the drama framework proposed

here. They tend to take an improvisational approach

to drama, close to the “comedy of the art” tradition,

first translated in a computational architecture by the

work of Hayes-Roth (Hayes-Roth et al., 1995). Ac-

cording to this paradigm, drama emerges from the in-

teraction of a set of characters, constrained to specific

roles. This approach – whose realization has been en-

couraged by the availability of conceptual and practi-

cal tools to implement the characters’ deliberation –

conflicts with the realization of a specific direction.

This situation corresponds to having a strongly un-

derdetermined direction, subsuming a large variety of

plots, or not having a specified direction at all.

It is worth noting that practical systems tend to

equate the autonomy of characters to the deliberative

processes and to use planning techniques for this pro-

cesses, relegating the representation of the characters’

mind to the use of truth maintaining systems and dele-

gating the plan monitoring activity to the built-in fea-

tures of planning–and–execution environments. This

approach, although effective in the practice, does not

allow the author to explicitly plan effects like frus-

tration or self-reflections that, although sophisticated,

are pervasive in drama. For example, turning back to

the excerpt analyzed in Section ??, think of the iter-

ated attempts performed by Hamlet to take revenge on

Claudius all along the play, and his frustrated attempt

to subtract Ophelia from the corruption of the court,

conducted through a rhetorical plan whose execution

encompasses monitoring actions of primary dramatic

importance.

As an example of this approach, consider the

‘Friends’ system (Cavazza et al., 2002), in which the

behavior of each character is generated by a hierar-

chical planner. Characters are committed to specific

goals (like seducing another character), and reactively

form intentions (i.e., partially instantiated plans) to

achieve them. The user interacts with as a ‘deus ex

machina’ with them by cooperating (for example, giv-

ing suggestions) or conflicting (for example, prevent-

ing actions); the actions of the user affect the behavior

of the characters, either influencing their future delib-

eration (characters’ high level plans are detailed out

only when execution approximates, leaving room for

the user’s advice) or forcing them to replan. The char-

acters are executed concurrently, so that further con-

flicts that are not envisaged by the autor may emerge

from their interaction.

From the author’s point of view, the use of the hi-

erarchical task network (HTN) planning paradigm al-

lows a more direct control of the development of the

A UNIFIED APPROACH FOR RECONCILING CHARACTERS AND STORY IN THE REALM OF AGENCY

435

plot, since it directly connects the characters’ behav-

ior with the specification of their goal; as a drawback,

it reduces the responsiveness of the system, that must

recur to replanning techniques to display a flexible be-

havior. In this sense, the system is a compromise be-

tween the autonomy of the characters at the actional

level and the control over the story, since their behav-

ior is constrained to a well defined set of hierarchical

plans. Although a proper representation of the char-

acters as agents is not present in the system, the use

of HTN planning indirectly gives a certain stability to

the behavior of characters, who keep at the same time

the capability to replan, a requirement posed by the

analysis of real plots. In practice, stating the drama

direction in terms of the characters’ goals releases the

control over story; from a theoretical perspective, it

collapses the distinction between the directional and

the actional level, since the former should abstract

from how actions are represented in the system.

In system described by (Pizzi et al., 2007), the fo-

cus is on the responsiveness of characters’ emotional

attitudes. The behavior of each character is generated

by a heuristic-search planner, and planning is limited

to the selection of the next action, to cope with asyn-

chronous user intervention without resorting to re-

planning. The planning operators represent ‘feelings’,

that manipulate the mental state of the characters. An

informal ontology, extracted from the novel inspir-

ing the story, Madame Bovary, defines how charac-

ters’ feelings vary and evolve as a consequence of the

changes in their beliefs, and how they affect the char-

acters’ behavior.

The author’s control over the system is confined to

the actional level, and consists of defining the initial

mental state of the characters and a set of planning

operators for each character. The resulting initial sit-

uation is open to opposite endings, depending on the

user’s input and the moment this input is provided.

The notion of conflict is mostly internal to the charac-

ters’ mental states, which can evolve towards different

final outcomes as a consequence of feelings.

This system is strongly committed to the actional

level of drama: within this dimension, it clearly priv-

ileges the accuracy of the emotional modeling of the

characters; it does not contain an explicit notion of

direction to provide a stronger control on the story

development; characters, in order to appear respon-

sive and thus to gain the user engagement, exhibit an

emotionally-based behavior rather than being driven

by explicitly coded intentions, encouraging the user to

explore, rather than to ‘direct’, the advancement of the

story. From the author’s point of view, the possibility

for the user to affect the beliefs and feelings of the

characters at any time, and the use of heuristic–search

planning (HSP), are likely to determine a large plan

space, leading to hypothesize a methodology consist-

ing of iterative testing to tune the behavior of the sys-

tem to the (unstated) author’s direction.

4 DISCUSSION AND

CONCLUSIONS

Although there is a general agreement about the role

played by characters and plot in practical systems,

the complex relations between the two have received

much less attention, a situation that can be partly at-

tributed to the fact that the notions of character and

story, taken in isolation, rely on generally agreed upon

models (autonomous agents, planning and graph the-

ories).

As a partial acknowledgment of the importance of

the direction to build an operational model of drama,

however, it has been amply recognized that the main

difficulty encountered by the interactive systems is to

reconcile the authorial control over the plot (i.e., the

direction) with the interaction with the user (see In-

troduction).

In this paper we have sketched a formal frame-

work to represent the domain of drama, aimed at ac-

counting for the interdependencies of the two levels of

drama, i.e., direction and actionality, at which the no-

tions of plot and characters are respectively situated.

The informal analysis of a classical example through

this framework has helped out to point out that a de-

tailed model of agency is necessary to grasp the be-

havior of characters in actual plot. Successful sys-

tems seem to confirm this assumption, since they rely

on some key notions of agent and multi-agent theories

(such as the properties of intentions, reactivity, meta-

deliberation aspects and so on) to reconcile story and

characters, although these notions are often only im-

plicitly modeled.

As a future work, we envisage the tasks of giving

to the framework a more complete formalization, and

to test its validity on a larger sample of systems and

plots, giving an accurate account of how the various

aspects of agency are tied to the properties of plot at

the directional level of drama, and how their explicit

modelling affects the expression of the author’s goals.

In particular, future research should address aspects

like the passive and active monitoring of action effects

(clearly visible in Ophelia’s attempts to gain Ham-

let’s attention in the first part of the scene analyzed in

Section ??), the reasoning about one’s own intentions

(visible, for example, in Hamlet’s sudden decision to

affect Ophelia’s behavior by convincing her to go to

a nunnery) and meta-deliberation capabilities (Ham-

ICAART 2009 - International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

436

let’s decision to return to his pretended madness as a

result of his personal failure with Ophelia, dropping

the infeasible goal to save Ophelia). Finally, since the

definition of drama lays out a multi-agent context, an

account is also needed of the relations between indi-

vidual agents, including cooperation, conflict and the

social and institutional relations that affect the moti-

vational structure of the characters.

REFERENCES

Aylett, R., Vala, M., Sequeira, P., and Paiva, A. (2007).

Fearnot!–an emergent narrative approach to virtual

dramas for anti-bullying education. LNCS, 4871:202.

Bates, J., Loyall, A., and Reilly, W. (1994). An architecture

for action, emotion, and social behaviour. Artificial

Social Systems, LNAI 830.

Bratman, M. E., Israel, D. J., and Pollack, M. E.

(1988). Plans and resource-bounded practical reason-

ing. Computational Intelligence, 4:349–355.

Cavazza, M., Charles, F., and Mead, S. (2002). Interact-

ing with virtual characters in interactive storytelling.

In Proc. of the First Int. Joint Conf. on Autonomous

Agents and Multiagent Systems.

Damiano, R., Lombardo, V., Nunnari, F., and Pizzo, A.

(2006). Dramatization meets information presenta-

tion. In Proceedings of ECAI 2006, Riva del Garda,

Italy.

Damiano, R., Lombardo, V., and Pizzo, A. (2005). Formal

encoding of drama ontology. In LNCS 3805, Proc. of

Virtual Storytelling 05, pages 95–104.

Damiano, R. and Pizzo, A. (2008). Emotions in drama char-

acters and virtual agents. In AAAI Spring Symposium

on Emotion, Personality, and Social Behavior.

Egri, L. (1946). The Art of Dramatic Writing. Simon and

Schuster, New York.

Hartmann, K., Hartmann, S., and Feustel, M. (2005). Mo-

tif definition and classification to structure non-linear

plots and to control the narrative flow in interactive

dramas. Third International Conference, ICVS, pages

158–167.

Hayes-Roth, B., Brownston, L., and vanGent, R. (1995).

Multi-agent collaboration in directed improvisation.

In First International Conference on Multi-Agent Sys-

tems, San Francisco.

Iurgel, I. (2006). Cyranus–an authoring tool for interactive

edutainment applications. In Pan, Z., Aylett, R., Di-

ener, H., Jin, X., Goebel, S., and Li, L., editors, Tech-

nologies for E-Learning and Digital Entertainment,

volume LNCS 3942. Springer.

Mateas, M. and Stern, A. (2003). Integrating plot, charac-

ter and natural language processing in the interactive

drama fa

´

ade. In TIDSE 03.

Mateas, M. and Stern, A. (2005). Structuring content in the

fa¸ade interactive drama architecture. In Proceedings

of Artificial Intelligence and Interactive Digital Enter-

tainment.

McKee, R. (1997). Story. Harper Collins, New York.

Medler, B. and Magerko, B. (2006). Scribe: A tool for

authoring event driven interactive drama. In Proc. of

TIDSE 2006, volume LNCS 4326, Darmstadt (Ger-

many). Springer.

Murray, J. (1998). Hamlet on the Holodeck. The Future of

Narrative in Cyberspace. The MIT Press, Cambridge,

MA.

Ortony, A., Clore, G., and Collins, A. (1988). The Cognitive

Stucture of Emotions. Cambrigde University Press.

Peinado, F. and Gerv

´

as, P. (2004). Transferring Game Mas-

tering Laws to Interactive Digital Storytelling. Proc.

of TIDSE 2004.

Pizzi, D., Charles, F., Lugrin, J., and Cavazza, M. (2007).

Interactive storytelling with literary feelings. In

ACII2007, Lisbon, Portugal, September. Springer.

Rao, A. and Georgeff, M. P. (1991). Modeling rational

agents within a BDI-architecture. In Proc. 2th Int.

Conf. Principles of Knowledge Representation and

Reasoning (KR:91), pages 473–484, Cambridge, MA.

Riedl, M. and Stern, A. (2006). Believable Agents and In-

telligent Story Adaptation for Interactive Storytelling.

Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on

Technologies for Interactive Digital Storytelling and

Entertainment (TIDSE06).

Riedl, M. and Young, M. (2006). From linear story gen-

eration to branching story graphs. IEEE Journal of

Computer Graphics and Applications, pages 23–31.

Ryan, M. (2006). Avatars of Story. University of Minnesota

Press.

Sgouros, N. (1999). Dynamic generation, management and

resolution of interactive plots. Artificial Intelligence,

107(1):29–62.

Spierling, U. (2007). Adding Aspects of “Implicit Cre-

ation” to the Authoring Process in Interactive Sto-

rytelling. Proceedings of Virtual Storytelling 2007,

LNCS 4871:13.

Swartjes, I. and Theune, M. (2006). A fabula model for

emergent narrative. Technologies for Interactive Dig-

ital Storytelling and Entertainment (TIDSE), LNCS,

4326:95–100.

Szilas, N. (2003). Idtension: a narrative engine for interac-

tive drama. In TIDSE 2003, Darmstadt (Germany).

Theune, M., Faas, S., Heylen, D., and Nijholt, A. (2003).

The virtual storyteller: Story creation by intelligent

agents. In Proceedings TIDSE 03, pages 204–215.

Fraunhofer IRB Verlag.

Wardrip-Fruin, N. and Harrigan, P. (2004). First Person:

New Media As Story, Performance, and Game. MIT

Press.

Weiss, S., M

¨

uller, W., Spierling, U., and Steimle, F. (2005).

Scenejo–an interactive storytelling platform. In Sub-

sol, G., editor, LNCS 3805, Proc. of Virtual Story-

telling 05, pages 77–80. Springer.

Wooldridge, M. and Parsons, S. (1999). Intention reconsid-

eration reconsidered. In M

¨

uller, J., Singh, M., and

Rao, A., editors, Proc . of ATAL-98, volume 1555,

pages 63–80. Springer-Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany.

A UNIFIED APPROACH FOR RECONCILING CHARACTERS AND STORY IN THE REALM OF AGENCY

437