A WORKFLOW MODEL FOR COLLABORATIVE

VIDEO ANNOTATION

Supporting the Workflow of Collaborative Video Annotation and Analysis

Performed in Educational Settings

Cristian Hofmann

1

, Nina Hollender

2

and Dieter W. Fellner

1

1

Interactive Graphics Systems Group, Technische Universität Darmstadt, Fraunhoferstr. 5, 64283 Darmstadt, Germany

2

Center for Development and Research in Higher Education, Technische Universität Darmstadt

Hochschulstr. 1, 64289 Darmstadt, Germany

Keywords: Video Annotation, Video Analysis, Computer-supported Collaborative Learning.

Abstract: There is a growing number of application scenarios for computer-supported video annotation and analysis in

educational settings. In related research work, a large number of different research fields and approaches

have been involved. Nevertheless, the support of the annotation workflow has been little taken into account.

As a first step towards developing a framework that assist users during the annotation process, the single

work steps, tasks and sequences of the workflow had to be identified. In this paper, a model of the

underlying annotation workflow is illustrated considering its single phases, tasks, and iterative loops that

can be especially associated with the collaborative processes taking place.

1 INTRODUCTION

Scenario: A group of students use a web-based tool

to analyse video sequences taken from TV panel

discussions with regard to the use of a range of

specific argumentation tactics. Their task is to mark

objects and sequences within the video, to annotate

these selections with text, and to compare and

discuss their results with peers or explore existing

video analysis databases.

Research activities in the area of computer-

supported video annotation have increased during

the last years. Corresponding solutions have been

implemented in various application areas, e.g.

interactive audiovisual presentations in e-Commerce

and edutainment or technical documentations

(Richter et al., 2007). In our research work, we focus

on the support of collaborative video analysis in

learning settings performed by applying video

annotation software. An important characteristic of

video is its ability to transfer and reflect the reality

in a direct manner (Ratcliff, 2003). Annotation

techniques provide referable multimedia documents

that serve as means of description, documentation,

and evidence of analytic results (Hagedorn et al.,

2008; Mikova and Janik, 2006). A growing number

of application scenarios for (collaborative) video

analysis in education can be identified. Pea and

colleagues (2006) report on a university course of a

film science department, in which two different

movie versions of the play „Henry V“ are analysed

by a group of students with respect to the text

transposition by different actors and directors. Other

examples for the application of video analysis in

education are motion analyses in sports and physical

education, or the acquisition of soft skills such as

presentation or argumentation techniques (Hollender

et al., 2008; Pea et al., 2006).

In previous research, a large number of different

research fields and approaches have been involved

in Video Annotation and Analysis Research.

Nevertheless, one relevant discipline has been little

taken into account: The support of the analysis

workflow, which comprises the management of

annotation data with related tasks and system

services. This is especially the case for collaborative

settings. Thus, a majority of today’s applications do

not consider the needs of the users regarding a

complete workflow in video annotation (Hagedorn

et al., 2008). We believe that an appropriate support

of that workflow will also improve learning

processes. By workflow-support, we mean the

199

Hofmann C., Hollender N. and W. Fellner D. (2009).

A WORKFLOW MODEL FOR COLLABORATIVE VIDEO ANNOTATION - Supporting the Workflow of Collaborative Video Annotation and Analysis

Performed in Educational Settings.

In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Computer Supported Education, pages 199-204

DOI: 10.5220/0001849101990204

Copyright

c

SciTePress

facilitation of loops and transitions between the

single workflow steps and tasks on the one hand. On

the other hand, appropriate tools and information

can be provided at the proper time, depending on the

current state of the work. By doing so, learners can

obtain information about 1.) which tasks they have

already accomplished, 2.) what is their current state,

and 3.) what are the next steps to do at any time of

the annotation process. Consequently, we expect a

discharge of learners and/or tutors with regard to the

use of such applications and hence an enhancement

of efficiency.

The contribution of this paper is the presentation

of a workflow model for computer-supported

collaborative video annotation. Our investigations

addressed the specific needs of users who work in

teams with a special focus on the application in

educational settings. The results base on interviews

and discussions conducted with experts and users

regarding the sequence of tasks and work steps

within the annotation process, as well as on a

summary and reflection of the existing literature. In

addition, we performed an analysis of the

functionalities, the user interface, and interaction

design of fifteen present applications.

2 RELATED WORK

Bertino, Trombetta, and Montesi (2002) presented a

framework and a modular architecture for interactive

video consisting of various information systems. The

coordination of these components is realized by

identifying inter-task dependencies with interactive

rules, based on a workflow management system. The

Digital Video Album (DVA) system is an

integration of different subsystems that refer to

specific aspects of video processing and retrieval. In

particular, the workflow for semiautomatic indexing

and annotation is focused (Zhang et al., 2003). Pea

and Hoffert (2007) illustrate a basic idea of the video

research workflow in the learning sciences (Pea and

Hoffert, 2007). In contrast to our research work, the

projects mentioned above do not or only to some

degree consider the process for collaborative use

cases. The reconsideration of such communicative

and collaborative aspects requires modifications and

enhancements of the existing approaches and

concepts.

3 A WORKFLOW MODEL FOR

COLLABORATIVE VIDEO

ANNOTATION

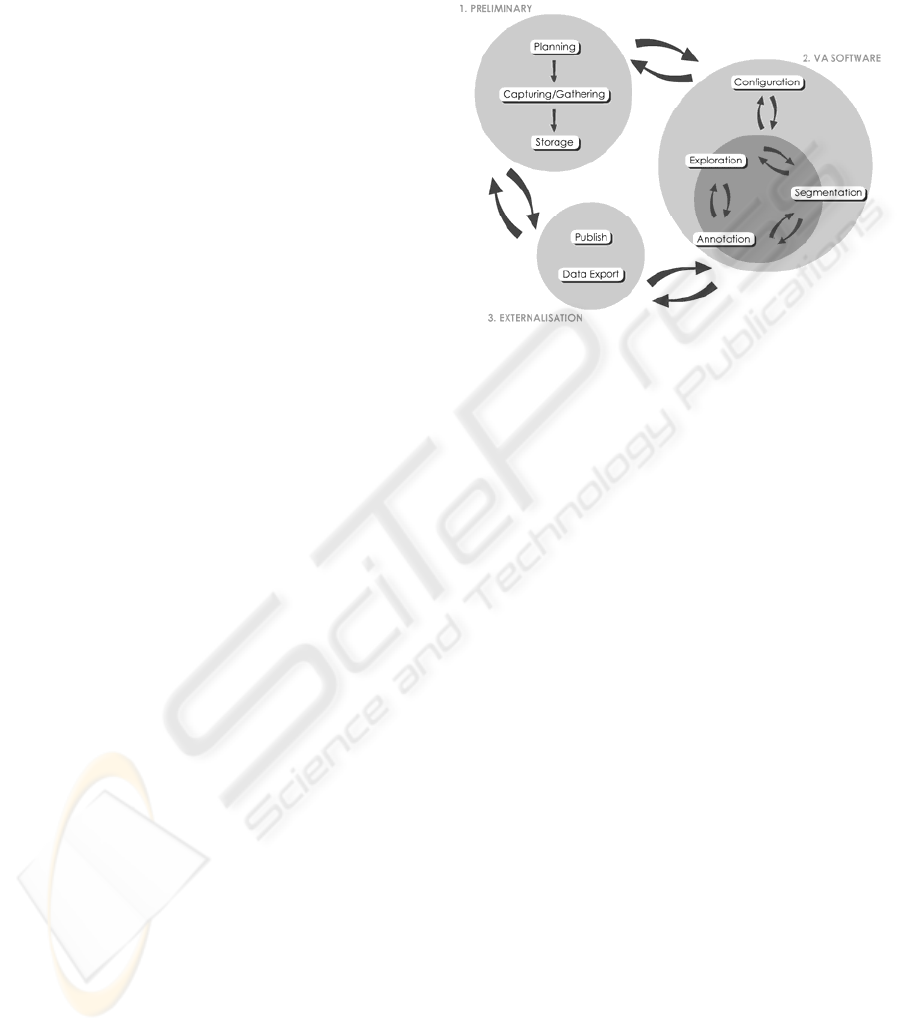

Figure 1: The collaborative video annotation workflow

model.

In order to design a collaborative video annotation

application that supports transitions between work

steps and loops within the collaborative process, we

first of all developed a model for the annotation

workflow. For this purpose, we conducted

interviews with experienced video analysts at the

Leibnitz Institute for Science Education in Kiel,

Germany, and at the Institute for Sports Science at

the Technische Universität Darmstadt, Germany.

Furthermore, we held discussions with researchers at

the Knowledge Media Research Center in Tübingen,

Germany, who had studied the collaborative design

of video-based hypermedia in university courses

(Stahl et al., 2006). Our model is also based on

existing literature related to video analysis

workflows (Baecker et al., 2007; Brugmann et al.,

2004; Hagedorn et al., 2008; Harrison and Baecker,

1992; Mikova and Janik, 2006; Pea and Hoffert,

2007; Ratcliff, 2003; Seidel et al., 2005). The

identified publications appeared to focus each on a

different essential part of the whole annotation

process. However, the publications do not fully

cover the aspects of team work. We therefore pooled

the single results into one common model, and in a

second step (and as our main contribution), the

model was extended by the description of

collaborative activities performed by a shared group

of video annotators. On that score, we integrated

conclusions from the collaborative hypermedia-

design courses into the models and concepts

referring to the annotation workflow. Additionally,

we performed an analysis of the functionalities, the

CSEDU 2009 - International Conference on Computer Supported Education

200

user interface, and the interaction design of fifteen

existing applications. By doing so, we were able to

tag the specific services provided by these tools, as

well as the tasks and activities that can be conducted

by users.

As demonstrated in Figure 1, the annotation

process can be divided into three main phases:

Preliminary, Working with the Video Annotation

Software, and Externalisation. In the following, the

particular items of these steps are going to be

pictured.

3.1 Preliminary

The preliminary phase includes any task and work

step that has to be accomplished before conducting

the video analysis using annotation software.

3.1.1 Planning

At the beginning of a project, several decisions have

to be made concerning the video capturing

procedure (if video recording is required), e.g., how

many cameras should be involved, if lighting is

required, or whether a storyboard needs to be created

(Pea and Hoffert, 2007; Ratcliff, 2003).

Furthermore, one must consider if there is any

additional data (like sensor or eye-tracking data) that

has to be captured in parallel with the video

recordings (Brugmann and Russel, 2004; Hagedorn

et al., 2008). From a methodical view, a theoretical

framework might need to be built up. The

framework implies the identification of research

areas, research questions and hypotheses (Seidel et

al., 2005). In the case of video analysis, the

definition of category systems is often required.

They may be either developed deductively based on

a theory, or inductively based on the video material

(Bortz and Döring, 2006; Link, 2006; Mikova and

Janik, 2006; Seidel et al., 2005).

3.1.2 Capturing/Gathering

In a next step, the video and additional data needs to

be recorded. If files already exist, the data can be

gathered from specific databases or storage media

(Hagedorn et al., 2008; Mikova and Janik, 2006; Pea

and Hoffert, 2007).

3.1.3 Storage

Depending on the format of the collected data, the

videos need to be encoded or digitalized to suitable

files (Mikova and Janik, 2006; Pea and Hoffert,

2007). Then, the data is organized and stored (Pea

and Hoffert, 2007). That can lead to a re-editing of

the video files to more granulated units (Hagedorn et

al., 2008; Stahl et al., 2006).

3.2 Working with the Video

Annotation Software

Generally, working with the video software

comprises activities from system configuration to

video segmentation and annotation procedures and

information sharing.

3.2.1 Configuration

Before starting the collaborative work, the

participants are tracked and assigned to accounts and

user groups. The allocation to groups results from

the specific tasks or bounded video parts that have to

be revised. Users are associated with specific roles

that particularly include access rights and

restrictions. Before or during the annotation process,

a group administrator is able to distribute the

annotation tasks among the individual users (Lin et

al., 2003; Volkmer et al., 2005). Furthermore,

specific project preferences can be adjusted and the

graphical user interface may be customized

(Brugmann and Russel, 2004). In video analysis

projects, if an already existing category system is

applied, or if a category system has been developed

deductively, the category system needs to be fed into

the system. The possibility to change and elaborate

category systems needs to be given, especially if an

inductive or consensual approach for the

development of a category system has been chosen

(Bortz and Döring, 2006).

The following three work steps – segmentation,

annotation and exploration – are regarded as one

(collaborative) unit. Pea and Hoffert (2007) describe

the video analysis process as an assembly of de-

composition activities (segmentation, coding,

categorization, and transcription) and acts of the re-

composition of video data (rating, interpretation,

reflection, comparison, and collocation). Activities

of de- and recomoposition are closely interrelated

(Bortz and Döring, 2004; Pea and Hoffert, 2007). It

is a complex process that contains circular and

recursive loops, in which the video analyst

alternately marks, transcribes and categorizes,

analyzes and reflects, and needs to conduct searches.

This process is accompanyied by data reviews,

comparisons, and consequently modifications (Pea

and Hoffert, 2007; Ratcliff, 2003; Stahl et al., 2006).

Hence, segmentation, annotation, and exploration, as

higher-level categories, also have to be considered

A WORKFLOW MODEL FOR COLLABORATIVE VIDEO ANNOTATION - Supporting the Workflow of Collaborative

Video Annotation and Analysis Performed in Educational Settings

201

related to each other. In collaborative use cases, any

data arising from segmentation, annotation can be a

collaborative contribution, and exploration also can

include collaborative activities (cp. Brugmann et al.,

2004; Brugmann and Russel, 2004; NRC, 1993).

Following, these three workflow items and their

collaborative aspects are going to be described.

3.2.2 Segmentation

Annotators start marking segments of interest and

chunking the video into subsets they want to refer to.

For this purpose, they may use manual,

semiautomatic, or automatic techniques (Finke,

2005; Kipp, 2008; Pea and Hoffert, 2007). Examples

are the semiautomatic keyframe method which is

accompanied by linear interpolation or automatic

approaches like object or scene detection, scene-

based event logging, or object of focus detection.

(Banerjee et al., 2004; Bertini et al., 2004; Finke,

2005; Hofmann and Hollender, 2007; Snoek and

Worring, 2005). Corresponding to the time code in

which an event takes place, users can define a point

in time (single video frame) or a time interval

(multiple following frames). Furthermore, an

enrichment of this temporal information with spatial

information is essential for almost every case of

video “pointing” (Finke, 2005; Hofmann and

Hollender, 2007; Kipp, 2008).

Video segments can be defined either by a single

person or by an assigned group in a collaborative

manner. Stahl et al. (2006) report on university

courses, in which students first discussed the video

segments they wanted to define, before actually

entering that information into the used application.

Thus, (textual) annotations that serve as

communication contributions are resources for the

coordination of collaborative segmentation

activities. Furthermore, in some of the identified use

cases, the segmentation task is partitioned and

assigned to individual users or groups. For example,

group A chunks the video according to a certain

characteristic 1, group B seeks for characteristic 2,

and so on. Furthermore, users or groups may also

work with different categorization systems.

3.2.3 Annotation

After segmenting the video, users continue with the

annotation of these subsets and pulling annotations

into order, usually within a layer-based timeline

(Link, 2006; Kipp, 2008). Different forms of

annotations have been identified. In general, they

can be summarized as any kind of additional

information (Finke, 2005; Stahl et al., 2006). One

type of annotation is the linking of metadata or

descriptive data. Apart from enriching video

segments with information like user data or

processing data, descriptive data also can be the

categorization based on a certain category system.

E.g., tagging is a useful method for collaboratively

organizing the amount of video-based information

(Baecker et al., 2007).

Users may describe observed behaviors, events,

or objects within the video. In most cases, they are

allowed to enter free textual annotations. Indeed,

also other types of media formats are possible

(Finke, 2005) During the annotation phase, a further

task can be the transcription of verbal and non-

verbal communication, which is often used in the

context of communication or interaction analyses

(Mikova and Janik, 2006). In video analysis, the

annotation phase also includes interpretation, rating,

and reflecting. These activities can be performed

either qualitatively, e.g. in discussions, or

quantitatively, by means of statistic methods

provided by specialized software (Hagedorn et al.,

2008; Pea and Hoffert, 2007).

Like the segmentation task, annotation may be

divided and distributed to different groups. In that

case, any user has got access to his or her group’s

annotations and is allowed to modify them. Thus,

annotated information becomes a shared

contribution (Finke, 2005; Hofmann and Hollender,

2007).

Communicational contributions constitute an

essential kind of annotation with respect to

collaboration. They enable the communication

between co-annotators as well as the organization of

common tasks. Most of the current applications

realize group communication by providing textual

comments similar to web forums. When users work

separatedly, they need to discuss their annotations,

conclusions, and the analysis process with other

participants (synchronous and/or asynchronous)

(Brugmann et al., 2004; Brugmann and Russel,

2004; NRC, 1993). Thus, discussion is a central

element within the collaborative annotation process.

Particularly in the context of consensual approaches,

discussion is a means of agreement and consistency

of different annotators’ results. Discussion often

leads to a return to previous steps of the workflow.

In the end, the final results of the annotation project

arise from iterative loops through the annotation

workflow, in which the data is modified and

adjusted. E.g., the interviewed experts at the IPN

report on a training phase that is conducted before

the actual video analysis on new video material. The

main goals are to develop basic analytic skills (Stahl

CSEDU 2009 - International Conference on Computer Supported Education

202

et al., 2006), perform checks for objectivity and

reliability, applying different annotator agreement

measures (Hagedorn et al., 2008; Link, 2006;

Mikova and Janik 2006; Seidel et al., 2005), and to

validate the deployed category system (Seidel et al.,

2005). As a consequence, these checks lead to a

return to the planning and configuration phases

(Mikova and Janik, 2006; Seidel et al., 2005).

3.2.4 Exploration

Searching and browsing always go along with

segmentation and annotation activities. Pea and

Hoffert (2007) assume that surveying one’s own

data is required to properly conduct an analysis.

Especially in collaborative annotation, users also

need to search for results of co-annotators, experts,

or other sources (Hollender et al., 2008). The

exploration of external information applies to

learning scenarios: The interview at the IPN

revealed that novice annotators use already analyzed

videos as training material and compare their own

results with the results of their expert colleagues

(Hollender et al., 2008).

Exploration of co-annotator’s data also can be an

issue in asynchronous collaborative projects which

proceed over a long timeframe. After being absent,

users may need to track the changes performed by

other annotators involved in the project. In this

context, they also need to browse chat or

commentary histories (Baecker et al., 2007).

Exploration also includes restructuring of the

data representation. With regard to this, annotators

are allowed to contrast relevant data with each other,

or to hide less important information. Pooling

commonly categorized information and making

statistical comparisons are part of video re-

composition (Pea and Hoffert 2007). According to

this, exploration also supports reflection. Thus, it

facilitates the consideration of multiple views of the

video. We take this as an important aspect with

regard to learning settings, since users are allowed to

obtain a view on the video’s contents beyond their

subjective point of view (Stahl et al., 2006; Volkmer

et al., 2005).

3.3 Externalisation

The externalisation phase includes activities without

the use of the annotation application, consisting of

any kind of publishing operations. It begins with

editing and converting the data into several formats,

and moves on to presenting this information in

corresponding media (Pea and Hoffert, 2007). E.g.,

it can be used for demonstration purposes (Mikova

and Janik, 2006). As mentioned above, databases of

analyzed video material can serve as digital resource

for information retrieval in following analysis

sessions. Furthermore, it is often necessary to export

data for further analytic inspection with specific

applications. Users create surveys, assemblies of

similarly categorized video subsets, and perform

comparisons of annotated data (Hagedorn et al.,

2008; Pea and Hoffert, 2007). The interviewed

experts report on exporting data to various formats,

such as tab-delimited text or transcription files.

Thus, further analytic activities can be executed with

tools and services that are not provided by the video

annotation application.

4 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

In this paper, we illustrate a workflow model for

video annotation performed in teams. We

particularly point out the iterative loops that are

passed through, especially in work steps performed

in a collaborative manner.

Based on the developed model, we are currently

working on the architecture design and

implementation of a web-based collaborative video

annotation application that supports transitions

between phases and sub tasks of the workflow, and

loops within the annotation process. In summary, we

expect to achieve elementary improvement of

interaction with the software.

REFERENCES

Abowd, G.D., Gauger, M., Lachenmann, A., 2003. The

Family Video Archive: an annotation and browsing

environment for home movies. In MIR '03, 5

th

ACM

SIGMM international Workshop on Multimedia

Information Retrieval. ACM Press, pp. 1-8.

Baecker, R. M., Fono, D., Wolf, P., 2007. Toward a Video

Collaboratory Video research in the learning sciences.

In Goldman, R., Pea, R., Barron, B., and Derry, S.J.

(ed.) Video Research in the Learning Sciences.

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 461-478.

Banerjee, S., Cohen, J., Quisel, T., Chan, A., Patodia, Y.,

Al-Bawab, Z., Zhang, R., Black, A., Stern, R.,

Rosenfeld, R., Rudnicky, A., Rybski, P. E. Veloso,

M., 2004. Creating multi-modal, user-centric records

of meetings with the carnegie mellon meeting recorder

architecture. In ICASSP 2004 Meeting Recognition

Workshop.

A WORKFLOW MODEL FOR COLLABORATIVE VIDEO ANNOTATION - Supporting the Workflow of Collaborative

Video Annotation and Analysis Performed in Educational Settings

203

Bertini, M., Del Bimbo, A., Cucchiara, R., Prati, A., 2004.

Applications ii: Semantic video adaptation based on

automatic annotation of sport videos. In MIR ´04, 6th

ACM SIGMM International Workshop on Multimedia

Information Retrieval. ACM Press, pp. 291-298.

Bertino, E., Trombetta, A., Montesi, D., 2002. Workflow

Architecture for Interactive Video Management

Systems. In Distributed and Parallel Databases,

Springer Netherlands, pp. 33-51.

Bortz, J., Döring, N., 2006. Forschungsmethoden und

Evaluation für Human- und Sozialwissenschaftler.

Springer. Berlin, 4

th

edition.

Brugman, H., Crasborn, O. A. & Russel, A., 2004.

Collaborative annotation of sign language data with

peer-to-peer technology. In LREC 2004, The fourth

international conference on Language Resources and

Evaluation. European Language Resources

Association, pp. 213-216.

Brugman, H., & Russel, A., 2004. Annotating multi-media

/ multi-modal resources with ELAN. In LREC 2004,

The fourth international conference on Language

Resources and Evaluation. European Language

Resources Association, pp. 2065-2068.

Finke, M., 2005. Unterstützung des kooperativen

Wissenserwerbs durch Hypervideo-Inhalte.

Dissertation, Technische Universität Darmstadt,

Germany.

Hagedorn, J., Hailpern, J. Karahalios, K.G., 2008. VCode

and VData: illustrating a new framework for

supporting the video annotation workflow. In AVI '08,

Working Conference on Advanced Visual Interfaces.

ACM Press, pp. 317-321.

Harrison, B.L. Baecker, R.M., 1992. Designing video

annotation and analysis systems. In CGI ’92,

Conference on Graphics interface. Morgan Kaufmann

Publishers, pp. 157-166.

Hofmann, C., Hollender, N., 2007. Kooperativer

Informationserwerb und -Austausch durch

Hypervideo. In Mensch & Computer 2007: Konferenz

für interaktive und kooperative Medien. Oldenbourg

Verlag, pp. 269-272.

Hollender, N., Hofmann, C., Deneke, M., 2008. Principles

to reduce extraneous load in web-based generative

learning settings. In Workshop on Cognition and the

Web 2008, pp. 7-14.

Lancy, D.F., 1993. Qualitative research in education,

Longman. New York.

Link, D., 2006. Computervermittelte Kommunikation im

Spitzensport, Sportverlag Strauß. Köln.

Lin, C.Y., Tseng, B.L. Smith, J.R., 2003. Video

Collaborative Annotation Forum: Establishing

Ground-Truth Labels on Large Multimedia Datasets.

In TRECVID 2003 Workshop.

Mikova, M., Janik, T., 2006. Analyse von

gesundheitsfördernden Situationen im Sportunterricht:

Methodologisches Vorgehen einer Videostudie. In

Mužík, V., Janík, T., Wagner, R. (ed.) Neue

Herausforderungen im Gesundheitsbereich an der

Schule. Was kann der Sportunterricht dazu beitragen?

MU. Brno, pp. 248-260.

National Research Council Comittee on a National

Collaboratory. National Collaboratories, 1993.

Applying information technology for scientific

research, Nation Academy Press. Washington, DC.

Kipp, M., 2008. Spatiotemporal Coding in ANVIL. In

LREC 2008, The sixth international conference on

Language Resources and Evaluation. European

Language Resources Association.

Pea, R., Hoffert, E., 2007. Video workflow in the learning

sciences: Prospects of emerging technologies for

augmenting work practices. In Goldman, R., Pea, R.,

Barron, B., Derry, S.J. (ed.) Video Research in the

Learning Sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

London, pp. 427-460.

Pea, R., Lindgren, R., Rosen, J. , 2006. Computer-

supported collaborative video analysis. In 7th

International Conference on Learning Sciences.

International Society of the Learning Sciences, pp.

516-521.

Ratcliff, D., 2003. Video Methods in Qualitative Research.

In Camic P.M., Rhodes, J.E., Yardley, L. (ed.)

Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology:

Expanding Perspectives in Methodology and Design,

American Psychological Association, pp. 113-130.

Richter, K., Finke, M., Hofmann, C., Balfanz, D., 2007.

Hypervideo. In Pagani, M. (ed.) Encyclopedia of

Multimedia Technology and Networking, Idea Group

Pub. 2

nd

edition.

Seidel, T., Dalehefte, I. M., Meyer, L. (ed.), 2005. How to

run a video study. In Technical report of the IPN

Video Study, Waxmann, Münster.

Snoek, C. G. M., Worring, M., 2005. Multimodal video

indexing: A review of the state-of-the-art. In

Multimodal Tools and Applications. Springer, pp. 5-

35.

Stahl, E., Finke, M., Zahn, C., 2006. Knowledge

Acquisition by Hypervideo Design: An Instructional

Program for Univiversity Courses, Journal of

Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia, 15, 3.

Academic Research Library, p. 285.

Volkmer, T., Smith, J. R., Natsev, A., 2005. A web-based

system for collaborative annotation of large image and

video collections: an evaluation and user study. In

ACM MULTIMEDIA '05, 13th Annual ACM

international Conference on Multimedia. ACM Press,

pp. 892-901.

Zhang, Q.Y., Kankanhalli M.S., Mulhem, P., 2003.

Semantic video annotation and vague query, In MMM

‘03, 9th International Conference on Multimedia

Modeling, pp. 190-208.

CSEDU 2009 - International Conference on Computer Supported Education

204